F. Scott Fitzgerald's Life In Letters

The Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald

Chapter 5: Hollywood, July 1937 – December 1940

xxx. TO: Carl Van Vechten

Postmarked July 5, 1937

ALS, 3 pp. Yale University

Argonaut/Southern Pacific stationery

Dear Carl: Being on this train “getting away from it all” makes me think of you + your occasional postcards, even if the splended pictures hadn’t done so.

Zelda + Scottie (do you remember her squabbled for them + got the two best to remember me by while I am on this buccaneering expedition—the first since—I am wrong, the second since we were out there together.

But nothing will ever be like that 1st trip and I have formed my Californian cosmology from that.

It was kind and generous of you to send them—do you remember the inadequacy in the Fitzgerald household you repaired with a beautiful shaker.

I miss both your work + our meetings but I hope you are obtaining what measure of happiness is allowed in this world.

Ever Devotedly Yours

Scott

I will remember you not to anyone in particular but to what ghosts of our former selves I may encounter under Pacific Skies.

xxx. TO Corey Ford

From Turnbull.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation

Culver City, California

[Early July, 1937]

Dear Corey:

These Texas lands are like crossing a sea—spiritually I mean, with a fat contract at the end and the loss of something for a year or so. Tho I find that the vast majority of __ __’s who yelp about that had nothing to lose, either talent or vitality, when they sold out—and at the moment with my play finished I'm no exception. Even Dotty's1 chief kick was, I imagine, that the precious lazybones never had to work so hard in her life. And it amuses me to see the squirming of one-opus geniuses like Lawson, Hermann and Saroyan who simply have no more to say. How simple to be a Communist under those conditions—one can explain away not only the world's inadequacies but one's own. After __ __'s long pull at the mammalia of the Whitneys he ought to be able to swim under a long way. He'll be under something else when the real trouble begins.

The only real holdout against Hollywood is Ernest. O'Neill, etc., are so damn rich that they don't count. Dos Passos has nibbled and Erskine Caldwell, whom I admire a lot, seems to have gone in. It's a pretty unsatisfactory business—I'm trying a special stunt to beat the game. I'm getting up at six and working till nine on my own stuff which I did before under similar circumstances when I was young. (This is confidential.) The boys who try to write creatively at night after a day in the studio or on Saturdays after work there are gypped from the start—also those who write “on vacations.” Nobody's ever gotten out that way and I'm not going to perish before one more book.

Oddly enough this book is like Paradise. Mine have alternated between being selective and blown up. Paradise and Gatsby were selective; The Beautiful and Damned and Tender aimed at being full and comprehensive—either could be cut by one-fourth, especially the former. (Of course they were cut that much but not enough.) The difference is that in these last two I wrote everything, hoping to cut to interest. In This Side of Paradise (in a crude way) and in Gatsby I selected the stuff to fit a given mood or “hauntedness” or whatever you might call it, rejecting in advance in Gatsby, for instance, all of the ordinary material for Long Island, big crooks, adultery theme and always starting from the small focal point that impressed me—my own meeting with Arnold Rothstein for instance. All this because you seem to sincerely like some of my work and I dare then assume that above might interest you somewhat.

So our meeting is postponed unless you come West tho I'll keep your address in my “immediate” file in case autumn finds me in New York.

Yours with cordial good wishes,

Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

1 Dorothy Parker.

xxx. From Thomas Wolfe To Hamilton Basso

[Box 95] [Oteen, N.C.]

July 13, 1937

Dear Ham:

<…>

Good-bye for the present, Ham. Write as soon as you can and let me know if you and Toto can come over and when you can come. Or if you prefer, I will come over and see you, if you just name a date. I got a letter from Sherwood Anderson just before I left New York. But I have had no time to answer it yet. He invited me to visit him and I believe the address is Troutdale, Virginia; but I left the letter in New York and shall not be able to accept his invitation. But I am going to ask him to let me know if he is coming here, and if he does I think it would be fine if all three of us could get together. I do not know where Scott is, but I suppose he is around here somewhere. He was in New York a month or so ago. I didn’t see him, but Max told me that he seemed to be much better. He had written some stories and had plans for new work and Max believed that he was going to pull out of the hole all right. With all my heart I hope so.

I was too busy in New York to keep up with current movements which were having an especially furious career this spring and I suppose by doing so. I have lost what is called prestige. This is too bad of course; however, like you and every man, I only have what I have, I am what I am. I don't believe there is much to report, except that the boys are having meetings, congresses and demonstrations all over the place and were carrying on the Spanish war with unabated vigor, using, it seemed to me, essentially the same appeals to idealism, democracy, civilization, etc., as were current among the propagandists whose similar activities they so much abhorred twenty years ago and have so bitterly denounced since. However, let them argue and deny as they please. It is the same old business—“Plus ca change plus c’est le meme chose." It’s the old army game. What I say is, "it’s spinach and to Hell with it." But I suppose you know all about these things and have kept informed on all these important doings. Spain and Marx have made some strange new bedfellows. ... So runs the world away.

<…>

xxx. TO: Thomas Wolfe

Mid-July 1937

ALS, 1 p. Harvard University

Pure Impulse

U.S.A.

1937

Dear Tom: I think I could make out a good case for your nessessity to cultivate an alter ego, a more conscious artist in you. Hasn’t it occurred to you that such qualities as pleasantness or grief, exuberance or cyniscism can become a plague in others? That often people who live at a high pitch often don’t get their way emotionally at the important moment because it doesn’t stand out in relief?

Now the more that the stronger man’s inner tendencies are defined, the more he can be sure they will show, the more nessessity to rarify them, to use them sparingly. The novel of selected incidents has this to be said that the great writer like Flaubert has consciously left out the stuff that Bill or Joe, (in his case Zola) will come along and say presently. He will say only the things that he alone see. So Mme Bovary becomes eternal while Zola already rocks with age. Repression itself has a value, as with a poet who struggles for a nessessary ryme achieves accidently a new word association that would not have come by any mental or even flow-of-consciousness process. The Nightengale is full of that.

To a talent like mine of narrow scope there is not that problem. I must put everything in to have enough + even then I often havn’t got enough.

That in brief is my case against you, if it can be called that when I admire you so much and think your talent is unmatchable in this or any other country

Ever your Friend

Scott Fitzg

xxx. TO: Edwin Knopf

CC, 2 pp. Princeton University

Hollywood, California

July 19, 1937

Dear Eddie:

A sight of me is Zelda’s (my wife’s) life line, as the doctor told me before I left. And I’m afraid the little flying trips would just be for emergencies.

I hate to ask for time off. I’ve always enjoyed being a hard worker, and you’ll find that when I don’t work through a Saturday afternoon, it’s because there’s not a thing to do. So just in case you blew off your head, (as David Belasco so tactfully put it), I’d like to put the six weeks a year, one week every two months, into the contract.

It will include everything such as the work left over from outside, as indicated below.

First here is a memo of things that might come up later.

Stories sold but not yet published

The Pearl and the Fur |

—Pictorial Review |

Make Yourself at Home |

|

Gods of the Darkness |

—Red Book |

In the Holidays |

—Esquire |

Pub Room 32 |

|

Oubliette |

|

New York (article) |

—Cosmopolitan |

Early Success |

Cavalcade |

Unsold but in the Possession of my Agent in June, 1937

Financing Finnegan

Dentist’s Appointment

Offside Play

(All the above belongs to the past)

In Possession

One play (small part of last act to do.)

To write sometime during the next two years

2 Sat. Eve Post Stories

(I’ve never missed a year in the Post in seventeen years)

1 Colliers Story (advance paid)

3 Short Esquire pieces (advance paid)

So the total time I should ask for over two years would be twelve weeks to write these things while near my wife. It could be allotted as two weeks apiece for the stories, a week apiece for the articles, three weeks for finishing Act III of the play. Though if convenient, I shall in practice, use the weeks singly.

Notes:

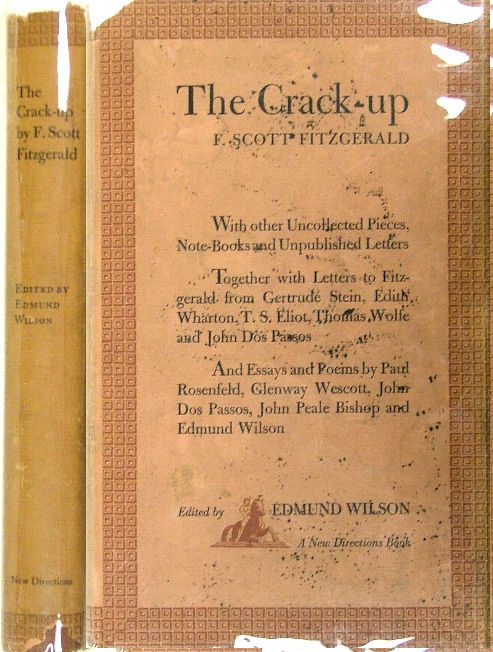

“The Pearl and the Fur” published in 2017; “Make Yourself at Home” appears to have been published as “Strange Sanctuary,” Liberty (December 9, 1939); “Pub Room 32” (Pub added in holograph.) published as “The Guest in Room Nineteen”; “Oubliette” published as “The Long Way Out”; “My Lost City” was first published in The Crack-Up.

Dentist’s Appointment published as “The End of Hate,” Collier’s (June 22, 1940); Offside Play published in 2017.

This play had the working title “Institution Humanitarianism”; it was never published or produced.

Fitzgerald did not appear in the Post after 1937.

Collier’s accepted “The End of Hate” for this advance.

Fitzgerald’s MGM contract stipulated that he had the right to work on his own writing during layoff periods.

xxx. TO: Anthony Powell

TLS, 1 p. Powell

MGM letterhead. Culver City, California

July 22, 1937

Dear Powell:

Book came.2 Thousand thanks. Will write when I have read it.3

When I cracked wise about Dukes, didn't know Mrs. Powell was a Duke. I love Dukes—Duke of Dorset, The Marquis Steyne, Freddie Bartholomew's grandfather the old Earl of Treacle.

When you come back, I will be in a position to have you made an assistant to some producer or Vice President, which is the equivalent to a Barony.

Regards, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Notes:

2 Powell's novel From a View to a Death (1933).

3 Powell did not receive a second letter from Fitzgerald.

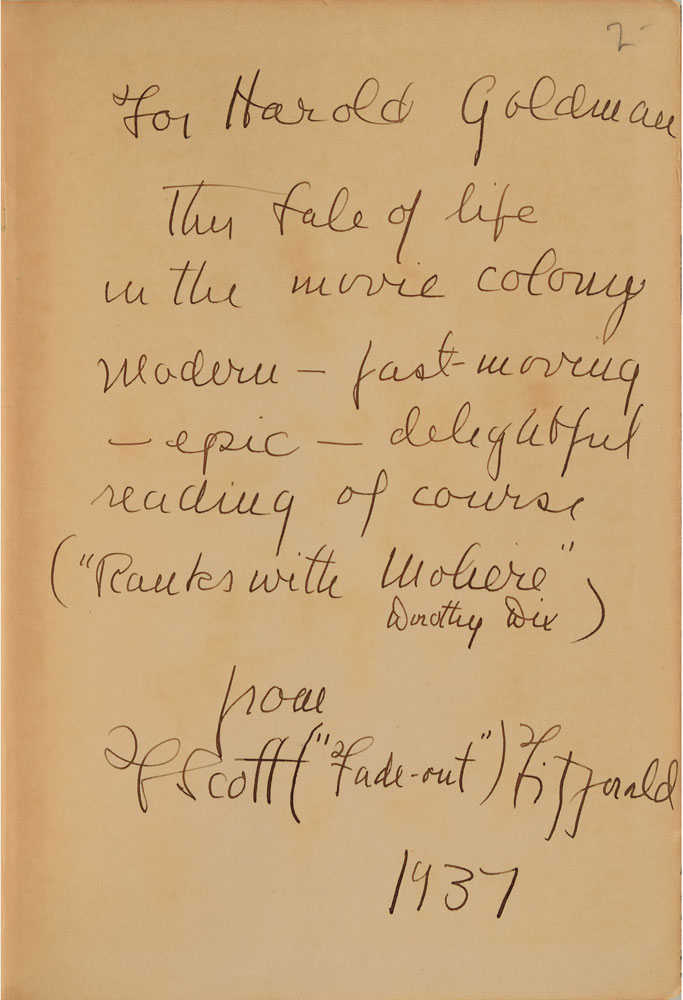

xxx. Inscription TO: Harold Goldman

July, 1937

Inscription on the first free end page in This Side of Paradise (later printing - NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931). Auction.

For Harold Goldman, this tale of life in the movie colony modern—fast-moving—epic—delightful reading of course, ('Ranks with Moliere,' Dorothy Dix), from F. Scott ('Fade-Out') Fitzgerald, 1937.

Notes:

The rear pastedown bears an affixed label from the Stanley Rose Bookshop, an important gathering place for the era's Hollywood literati, located on Vine Street off Hollywood Boulevard. Fitzgerald's contract for A Yank at Oxford movie dates July 7-26; Goldman worked with Fitzgerald on this movie.

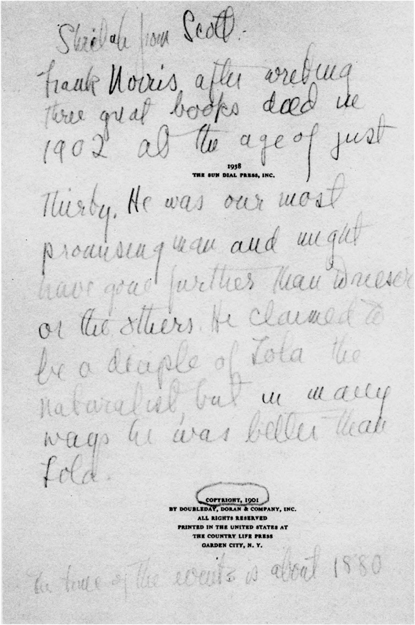

xxx. FROM: Thomas Wolfe

[from The Crack-Up, 1945]

July 26, 1937

Mr. F. Scott Fitzgerald

c/o Charles Scribners’ Sons

597 Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C.

Dear Scott:

I don’t know where you are living and I’ll be damned if I’ll believe anyone lives in a place called “The Garden of Allah,” which was what the address on your envelope said. I am sending this on to the old address we both know so well.

The unexpected loquaciousness of your letter struck me all of a heap. I was surprised to hear from you but I don’t know that I can truthfully say I was delighted. Your bouquet arrived smelling sweetly of roses but cunningly concealing several large-sized brick-bats. Not that I resented them. My resenter got pretty tough years ago; like everybody else I have at times been accused of “resenting criti[ci]sm” and although I have never been one of those boys who break out in a hearty and delighted laugh when someone tells them everything they write is lousy and agree enthusiastically, I think I have taken as many plain and fancy varieties as any American citizen of my age now living. I have not always smiled and murmured pleasantly “How true,” but I have listened to it all, tried to profit from it where and when I could and perhaps been helped by it a little. Certainly I don’t think I have been pig-headed about it. I have not been arrogantly contemptuous of it either, because one of my besetting sins, whether you know it or not, is a lack of confidence in what I do.

So I’m not sore at you or sore about anything you said in your letter. And if there is any truth in what you say— any truth for me—you can depend upon it I shall probably get it out. It just seems to me that there is not much in what you say. You speak of your “case” against me, and frankly I don’t believe you have much case. You say you write these things because you admire me so much and because you think my talent unmatchable in this or any other country and because you are ever my friend. Well Scott I should not only be proud and happy to think that all these things are true but my respect and admiration for your own talent and intelligence are such that I should try earnestly to live up to them and to deserve them and to pay the most serious and respectful attention to anything you say about my work.

I have tried to do so. I have read your letter several times and I’ve got to admit it doesn’t seem to mean much. I don’t know what you are driving at or understand what you expect or hope me to do about it. Now this may be pig-headed but it isn’t sore. I may be wrong but all I can get out of it is that you think I’d be a good writer if I were an altogether different writer from the writer that I am.

This may be true but I don’t see what I’m going to do about it. And I don’t think you can show me and I don’t see what Flaubert and Zola have to do with it, or what I have to do with them. I wonder if you really think they have anything to do with it, or if this is just something you heard in college or read in a book somewhere. This either—or kind of criticism seems to me to be so meaningless. It looks so knowing and imposing but there is nothing in it. Why does it follow that if a man writes a book that is not like Madame Bovary it is inevitably like Zola. I may be dumb but I can’t see this. You say that Madame Bovary becomes eternal while Zola already rocks with age. Well this may be true—but if it is true isn’t it true because Madame Bovary may be a great book and those that Zola wrote may not be great ones? Wouldn’t it also be true to say that Don Quixote or Pickwick or Tristram Shandy “become eternal” while already Mr. Galsworthy “rocks with age.” I think it is true to say this and it doesn’t leave much of your argument, does it? For your argument is based simply upon one way, upon one method instead of another. And have you ever noticed how often it turns out that what a man is really doing is simply rationalizing his own way of doing something, the way he has to do it, the way given him by his talent and his nature, into the only inevitable and right way of doing everything—a sort of classic and eternal art form handed down by Apollo from Olympus without which and beyond which there is nothing. Now you have your way of doing something and I have mine, there are a lot of ways, but you are honestly mistaken in thinking that there is a “way.”

I suppose I would agree with you in what you say about “the novel of selected incident” so far as it means anything. I say so far as it means anything because every novel, of course, is a novel of selected incident. There are no novels of unselected incident. You couldn’t write about the inside of a telephone booth without selecting. You could fill a novel of a thousand pages with a description of a single room and yet your incidents would be selected. And I have mentioned Don Quixote and Pickwick and The Brothers Karamazov and Tristram Shandy to you in contrast to The Silver Spoon or The White Monkey as examples of books that have become “immortal” and that boil and pour. Just remember that although Madame Bovary in your opinion may be a great book, Tristram Shandy is indubitably a great book, and that it is great for quite different reasons. It is great because it boils and pours—for the unselected quality of its selection. You say that the great writer like Flaubert has consciously left out the stuff that Bill or Joe will come along presently and put in. Well, don’t forget, Scott, that a great writer is not only a leaver-outer but also a putter-inner, and that Shakespeare and Cervantes and Dostoevsky were great putter-inners—greater putter-inners, in fact, than taker-outers and will be remembered for what they put in—remembered, I venture to say, as long as Monsieur Flaubert will be remembered for what he left out.

As to the rest of it in your letter about cultivating an alter ego, becoming a more conscious artist, my pleasantness or grief, exuberance or cynicism, and how nothing stands out in relief because everything is keyed at the same emotional pitch—this stuff is worthy of the great minds that review books nowadays—the Fadimans and De Votos—but not of you. For you are an artist and the artist has the only true critical intelligence. You have had to work and sweat blood yourself and you know what it is like to try to write a living word or create a living thing. So don’t talk this foolish stuff to me about exuberance or being a conscious artist or not bringing things into emotional relief, or any of the rest of it. Let the Fadimans and De Votos do that kind of talking but not Scott Fitzgerald. You’ve got too much sense and you know too much. The little fellows who don’t know may picture a man as a great “exuberant” six-foot-six clodhopper straight out of nature who bites off half a plug of apple tobacco, tilts the corn liquor jug and lets half of it gurgle down his throat, wipes off his mouth with the back of one hairy paw, jumps three feet in the air and clacks his heels together four times before he hits the floor again and yells “Whoopee, boys I’m a rootin, tootin, shootin son of a gun from Buncombe County—out of my way now, here I come!”—and then wads up three-hundred thousand words or so, hurls it back at a blank page, puts covers on it and says “Here’s my book!”

Now Scott, the boys who write book reviews in New York may think it’s done that way; but the man who wrote Tender Is the Night knows better. You know you never did it that way, you know I never did, you know) no one else who ever wrote a line worth reading ever did. So don’t give me any of your guff, young fellow. And don’t think I’m sore. But I get tired of guff—I’ll take it from a fool or from a book reviewer but I won’t take it from a friend who knows a lot better. I want to be a better artist. I want to be a more selective artist. I want to be a more restrained artist. I want to use such talent as I have, control such forces as I may own, direct such energy as I may use more cleanly, more surely and to better purpose. But Flaubert me no Flauberts, Bovary me no Bovarys. Zola me no Zolas. And exuberance me no exuberances. Leave this stuff for those who huckster in it and give me, I pray you, the benefits of your fine intelligence and your high creative faculties, all of which I so genuinely and profoundly admire.

I am going into the woods for another two or three years. I am going to try to do the best, the most important piece of work I have ever done. I am going to have to do it alone. I am going to lose what little bit of reputation I may have gained, to have to hear and know and endure in silence again all of the doubt, the disparagement and ridicule, the post-mortems that they are so eager to read over you even before you are dead. I know what it means and so do you. We have both been through it before. We know it is the plain damn simple truth.

Well, I’ve been through it once and I believe I can get through it again. I think I know a little more now than I did before, I certainly know what to expect and I’m going to try not to let it get me down. That is the reason why this time I shall look for intelligent understanding among some of my friends. I’m not ashamed to say that I shall need it. You say in your letter that you are ever my friend. I assure you that it is very good to hear this. Go for me with the gloves off if you think I need it. But don’t De Voto me. If you do I’ll call your bluff.

I’m down here for the summer living in a cabin in the country and I am enjoying it. Also I’m working. I don’t know how long you are going to be in Hollywood or whether you have a job out there but I hope I shall see you before long and that all is going well with you. I still think as I always thought that Tender Is the Night had in it the best work you have ever done. And I believe you will surpass it in the future. Anyway, I send you my best wishes as always for health and work and success. Let me hear from you sometime. The address is Oteen, North Carolina, just a few miles from Asheville, Ham Basso, as you know, is not far away at Pisgah Forest and he is coming over to see me soon and perhaps we shall make a trip together to see Sherwood Anderson. And now this is all for the present—unselective, you see, as usual. Good bye Scott and good luck.

Ever yours,

Tom Wolfe

Notes:

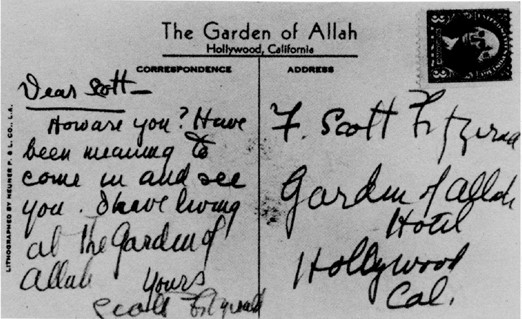

old address - Care of Scribners

The Garden of Allah - This was Fitzgerald’s real address, an apartment hotel, in Hollywood.

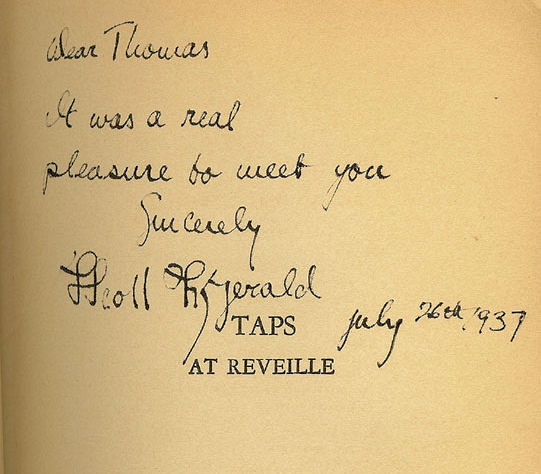

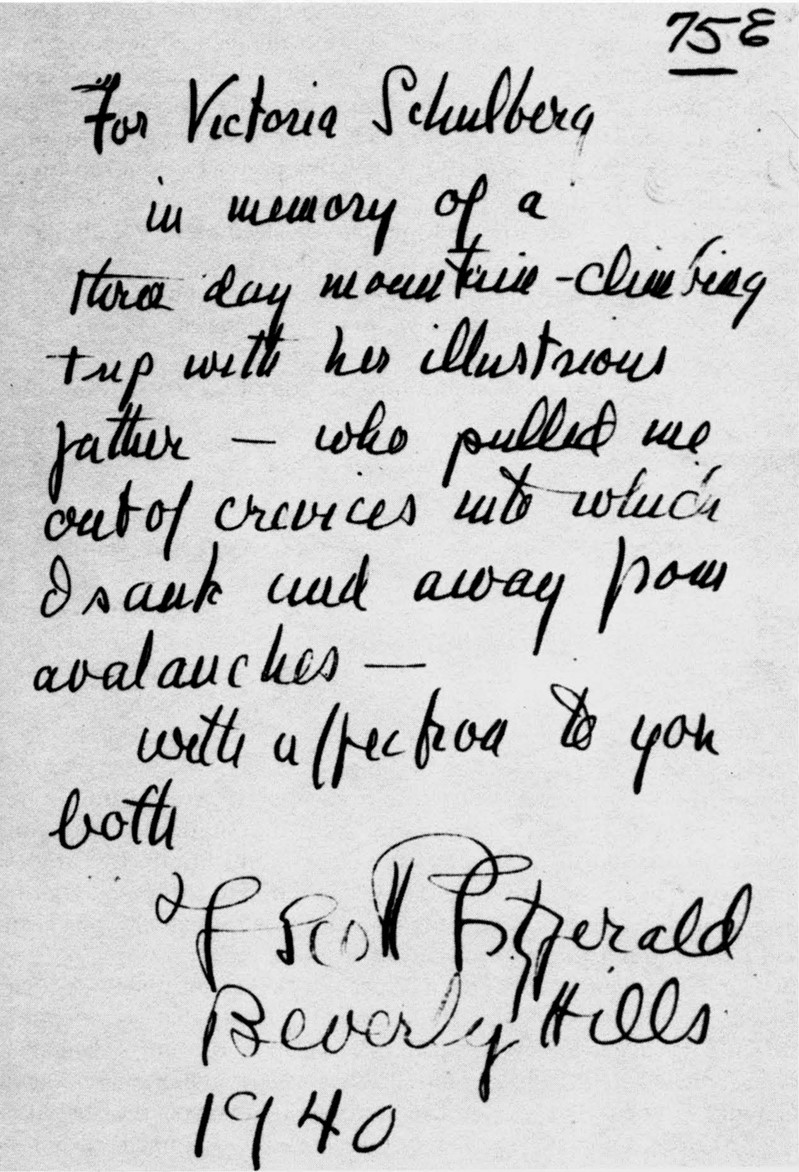

xxx. TO: Thomas

July 26, 1937

Inscription in Taps At Reveille (1934).

Dear Thomas

It was a real pleasure to meet you

Sincerely, F. Scott Fitzgerald

July 26, 1937

xxx. From Thomas Wolfe To Hamilton Basso

[Oteen, N.C.]

July 29, 1937

Dear Ham:

Pick out a week end, any one you like 1, and I'll make it fit with my own plans which are very simple ones. I intend to keep at work, and so far as I know, except for the hordes of thirsty tourists who just happen in casually to look at the elephant. I have no definite engagements... Except for casual intrusions—people driving up to demand if I’ve seen anything of a stray cocker spaniel, gentlemen appearing through the woods with a four-pound steak saying their name is McCracken and I met them on the train four weeks ago and they always bring their own provisions with them, and the local Police Court judge and the leading hot-dog merchant, and friends of my shooting scrape in Yancey County with bevies of wild females—all of which has and is continuing to happen—I have practically no company at all out here. At any rate it’s all been very interesting and instructing and in spite of Hell and hilarity I am pushing on with my work. You come on over anyway: I can’t promise you long twenty-four hour periods of restful seclusion while we meditate upon the problems of life and art, but you may have an instructive and amusing time, and of course I’d love to see you and talk it over with you.

I had a letter from Scott, and the surprise of hearing from him was so great you could have knocked me over with a brick bat. It was, for him, an amazingly long letter and a very earnest one. It was all about Art— and more especially my own lack of it. He passed out some very graceful compliments about my “unmatchable talents" and so on, and how he wouldn’t be doing all this if he wasn’t my friend, etc.—and then let me have it. It was all very much like those famous lines of my favorite poem:

“It was all very well to dissemble your love

—But why did you kick me downstairs?”

I couldn’t make out very well what he was driving at and told him so. There was a whole lot in it about Flaubert and Zola and “Madame Bovary” and how much greater Flaubert is than Zola, etc.—all of which may be true, but like the celebrated flowers that bloom in the spring, have nothing to do with the case. I let him have it with both barrels when I answered him, and I hope the experience will do him good. I know he will understand I wasn’t a bit sore and enjoyed writing a letter and a chance of ribbing him a little. He has come out apparently as a classical selectionist and was telling me that Flaubert would be remembered as a great writer for the things he left out. I answered, not, I thought un- neatly that Shakespeare and Cervantes and Tolstoi and Dostoievsky would be remembered as great writers for what they put in and that a great writer was not only a great leaver-outer but a great putter-inner also. Anyway I had some fun and I know Scott won’t mind it. His letter was postmarked Los Angeles and I don’t know whether he has got a job at Hollywood or not. His letter sounded more stable and cheerful, and I hope that everything is going better with him.

My Chickamauga story, which I liked so well myself, has now been honored with rejection slips by most of the nation’s eminent popular magazines. Harper’s also turned it down the other day with a pompous note from Mr. Hartman 2 to the effect that they would like a real Wolfe story, but they supposed this was impossible since Scribners had a stranglehold on the author’s best work. Well the comical pay-off on this is that Scribner’s have no hold at all, not even a feeble clasp. I have had only one piece in the magazine in three years, and that not one of the better ones, and Perkins has been panting to get hold of ’’Chickamauga” which Harper’s has just rejected. I don’t know whether his pants will cease when he has read the story, but I hope not 3. At any rate I'm gathering experience. Mr. Stout of The Saturday Evening Post allows as how my “No More Rivers" is a good story after page twenty and that they'd be very seriously concerned if I’d agree to cut the first twenty pages to four. As I remember it, the beautiful girl with the husky voice makes her appearance on page twenty—so that’s that.

I’ve just taken time out to have pictures of myself, the cabin and all three of us made by a beautiful lady and her escort, Judge Phil Cocke, who weighs 340 on the hoof and is one of Asheville’s famous and eminent characters. I like the Judge and the Judge curiously seems to like me; certainly I’ve never had as devoted and accurate a reader—he hasn’t forgotten a comma or a semicolon, he annotates my book with the names of the "real” characters, and I have heard that he was especially touched and delighted because he thinks I referred to him and a very celebrated lady in Asheville who bore the name of Queen Elizabeth and who at one time was the Empress of the Red Light District. Of course, I admit nothing, I just look coy and innocent—but if that’s the way they want to have it, I suppose no one can stop them. Anyway we are having fun, you must come over. This is all for the present, write and let me know what time suits you. Meanwhile, with love to you and Toto,

Notes

1 Basso had written that he would come and spend a weekend at Wolfes cabin.

2 Lee Hartman was editor of Harper's Magazine at this time.

3 The editors of Scribner's Magazine, which by this time was virtually independent of the publishing house of Scribners, declined “Chickamauga” soon after this.

xxx. TO: F. Scott Fitzgerald From F. Scott Fitzgerald

Summer 1937

Postcard (not mailed). Princeton

Dear Scott

—How are you? Have been meaning to come in and see you. I have living at the Garden of Allah.

Yours, Scott Fitzgerald.

xxx. TO: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

TL(CC), 1 p. Princeton University

Hollywood, California

Sept. 4, 1937

Dear Joe:

This letter is only valid in case you like the script very much.2 In that case, I feel I can ask you to let me try to make what cuts and rearrangements you think necessary, by myself. You know how when a new writer comes on a repair job he begins by cutting out an early scene, not realizing that he is taking the heart out of six later scenes which turn upon it. Two of these scenes can't be cut so new weak scenes are written to bolster them up, and the whole tragic business of collaboration has begun—like a child's drawing made “perfect” by a million erasures.

If a time comes when I'm no longer useful, I will understand, but I hope that this work will be good enough to earn me the right to a first revise to correct such faults as you may find. Then perhaps I can make it so strong that you won't want any more cooks.8

Yours,

P.S. My address will be, Highlands Hospital, Ashville, N.C., where my wife is a patient. I will bring back most of the last act with me.

Notes:

2 Fitzgerald had written the first draft of the screenplay for Three Comrades alone and was concerned that he would be assigned a collaborator. See F. Scott Fitzgerald's Screenplay for Three Comrades (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1978).

3 On 9 September Mankiewicz wired Fitzgerald in Charleston, S.C., complimenting him on the script and assuring him that he would not have to work with a collaborator. When Fitzgerald returned to Hollywood, E. E. Paramore was assigned to collaborate with him on Three Comrades.

xxx. TO Helen Hayes

From Turnbull.

[The Garden of Allah Hotel] [Hollywood, California]

September 16, 1937

Dear Helen:

You left so precipitately (to my mind) that I'm not going to blame myself for not being on hand. Called up Scottie half an hour after you'd gone to suggest that we make a farewell call on you; then I sent a wire to Mrs. MacArthur on the train, but it was returned—I guess you were just plain Helen Hayes again. (I see, by the way, that the Basil Rath-bone story leaked out, to my great delight.)

Helen, I'm not going to overwhelm you with thanks, but if you ever get too old to play Queen Victoria, I'm going to write a companion piece to Shaw's Methuselah for you that will eke out a living for you and Charlie and Mary during your declining years.

As a sort of a “wake” for you, Scottie and I ran off Madeleine Claudet the day you left, in a projection room. Charlie dropped in, and the Fitzgeralds contributed appropriate tears to the occasion—an upshot which, as you will remember, Garbo failed to evoke from this hardened cynic, so I think you have a future. Remember to speak slowly and clearly and don't be frightened—the audience is just as scared as you are. Maxwell Anderson's line should be spoken with a chewing motion and an expression of chronic indigestion.

I'll now tell you all about Mary's education, as I am a licensed nuisance on the subject. I think it is impossible to get a first rate American governess who will not make home a hell. That's reason number one for procuring a French, English or German number who will have a precise knowledge of her so-called “place.” The position of a governess, which is halfway between an employee and a servant, is difficult for anyone to keep up with dignity—that is, to be a sort of an ideal friend to the child and yet maintain an unobtrusive position in regard to mama and papa. It is utterly un-American, and I have never seen one of our countrywomen who was really successful at it. They don't succeed in passing on any standards, save those of the last shoddy series of movies. On the contrary, from a European upper servant, a child learns many short cuts, ways to dispose of those ordinary problems that irk us in youth. The business of politeness is usually deftly handled without any nonsense—and what a saving! The self-consciousness, if any, is eradicated smoothly and easily; the nerves are somehow cushioned by a protective pillow of good form, something which would be annoying to a formed adult but for a child is a big saving of wear and tear. We can all manufacture our unconventionality when the time comes and we have earned the right to it, but this country is filled with geniuses without genius, without the faintest knowledge of what work is, who were brought up on the Dalton system or some faint shadow of it. As I told you, it was tried and abandoned in Russia after three years. It is an attempt to let the child develop his ego and personality at any cost to himself or others—a last gasp of the ideas of Jean Jacques Rousseau. As a practice against too much repression, such as sending a shy girl to a strict convent, it had its value, but the world, especially America, has swung so far in the opposite direction that I can't believe it is good for one American child in a hundred thousand. Certainly not for one born in comparatively easy circumstances.

I have said my say on the subject, welcome or not, because I know you will be faced with some such problem soon when Miss X outgrows her usefulness. The pace of American life simply will not permit a first-rate woman to take up such a profession. I think for very young children the very best negro nurses in the South are an exception. They at least stand for something and I think a child absolutely demands a standard. Those years can be passed without harm in some uncertainty as to where the next meal is coming from, but they can't be passed in an ethical void without serious damage to the child's soul, if that word is still in use. The human machinery which controls the sense of right, duty, self-respect, etc., must have conscious exercise before adolescence, because in adolescence you don't have much time to think of anything.

I have just come back from eight days in the East where I found Zelda much better than usual—we went to Charleston, South Carolina, for four days—and on my return here learned that the work had pleased the powers-that-be.

Scottie has finished her play and goes back to school with enthusiasm, though she paid me the tribute of a rare tear when I left her. She will remember this summer all her life, and moreover she will be marked by the idealism she has for you. She talked about you constantly—the things that you wisely did and wisely left undone. Do you mind being a shining legend?

Devotedly,

[Scott]

xxx. To Pete and Peggy Finney

[TS, signed] From The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 76, No. 3 (Spring 2015).

October 8, 1937

Dear Pete and Peggy:

The mystery of the missing daughter solved itself when your telegram came. I might have guessed she was with you, but it was absolutely arranged that she was to go on to New York to do some tutoring before school opened.1 I had visions of her being up in the pampas of Charlestown with the little Mackey girl, or else shopping herself around from house to house in Baltimore so that she could tear around madly with Bill the butcher or Bob the baker, or whatever that boy’s name is. 2 It seems that she had told her Aunt 3 and simply thought that I’d crawled back into my shell hole out here and put her out of my mind. The weakness was that the Obers didn’t know where she was either. 4 However, that’s ancient history.

So is her trip out here, but I must say that it was an “Alice in Wonderland” experience for her, and both of us kept wishing Peaches could have shared some of the excitements that were rife. She seems to have a little more poise and made a good impression, though the reports about talent scouts following her around are somewhat exaggerated. 5

I have just finished the script of THREE COMRADES (I guess she told you about it) and I’m reconciled to staying out here. It is the kind of life I need. I think I’m through drinking for good now, but it’s a help this first year to have the sense that you are under observation— everyone is in this town, and it wouldn’t help this budding young career to be identified with John Barleycorn. In freelance writing it doesn’t matter a damn what you do with your private life as long as your stuff is good; but I had gotten everything pleasant that drink can offer long ago, and really do not miss it at all and rather think of that last year and a half in Baltimore and Carolina as a long nightmare. A nightmare has its compensations but you wake up at the end of it feeling that life has moved on and left you standing still with ever greater problems to meet than before.6

Your kindness to Scottie is again appreciated. She has a fixation on Baltimore—partly because it was there that she first became conscious of boys. I think that this time she was old enough to realize that Baltimore boys are no more or less magical than any other boys, but the warm spot will always be there.

Ever yours with gratitude and affection, Scott Fitzgerald

Notes

1. Scottie had been in California with her father in September 1937. She traveled there with actress Helen Hayes (1900-1993), whose husband, the playwright and screenwriter Charles MacArthur (1895-1956), was a friend of Fitzgerald’s from New York and the early 1920s. Scott and Scottie then visited Zelda together, and Scottie evidently headed north alone to the Finneys while her father returned to Hollywood. Lanahan, Scottie, 83-85.

2. In letters of October and November 1937, in the Fitzgerald Papers, Scott teased Scottie about “Bob the Baker,” an unidentified Baltimore boy—or perhaps Fitzgerald’s collective term for several. See F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli, rev. ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 338-39.

3. Rosalind Sayre Smith (1889-1979), Zelda’s sister, lived in New York and participated actively in Scottie’s life. Of her, Scottie later said, “She was a loving soul as long as she approved of what you did[.]” Lanahan, Scottie, quoted at 210.

4. The family of Harold Ober, Fitzgerald’s agent, welcomed Scottie regularly during her Ethel Walker and Vassar years. Scottie called Harold and his wife, Anne, Gramps and Auntie. At Scottie’s wedding to Samuel Jackson “Jack” Lanahan (1918-1998, Class of 1941) in 1943, Ober gave away the bride. For more on Scottie and the Obers, see Lanahan, Scottie, 142-50.

5. These reports were made by Sheilah Graham, Hollywood gossip columnist and by now Fitzgerald’s lover, in her weekly column “Hollywood Today: A Gadabout’s Notebook.”

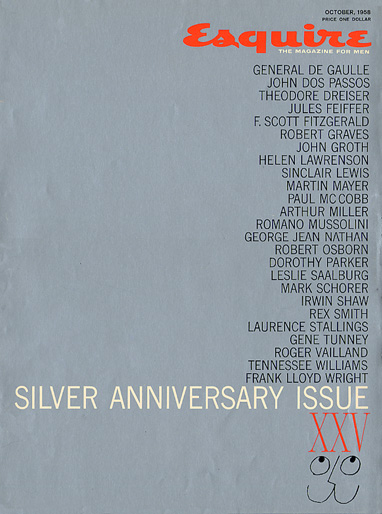

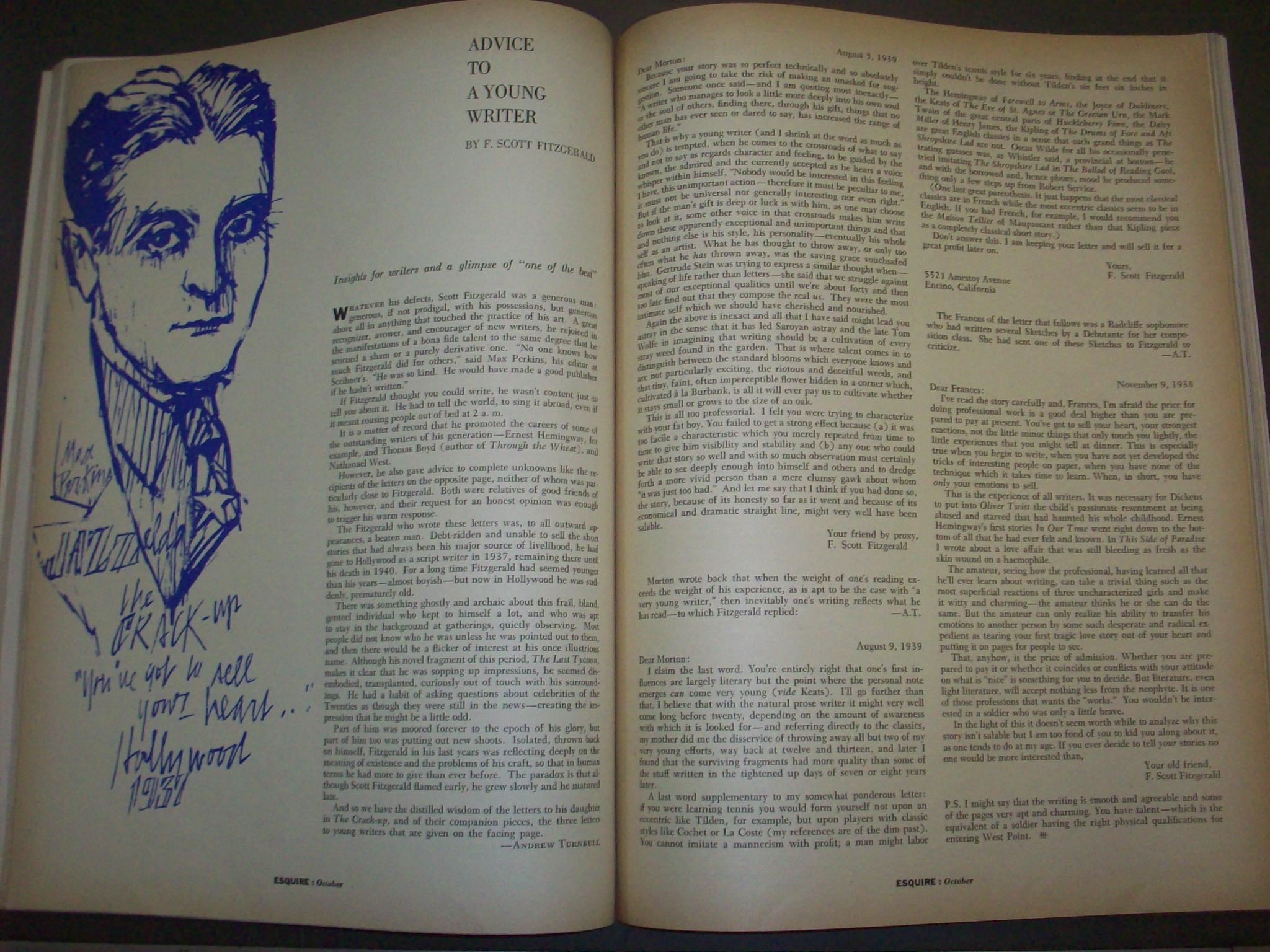

6. Fitzgerald’s chronicle of this terrible time, “The Crack-Up,” was serialized in the February, March, and April 1936 numbers of Esquire.

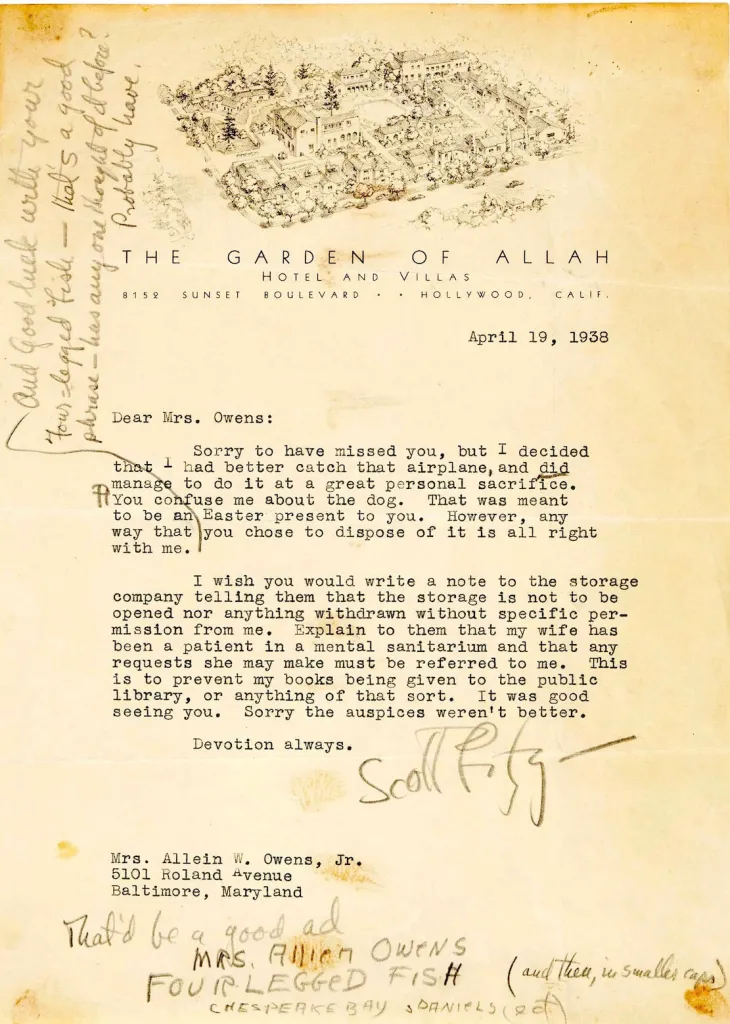

xxx. TO Mrs. Allein Owens

From Turnbull.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation Culver City, California

October 8, 1937

Dear Mrs. Owens:

Thanks for your letter. I think of you often and am enclosing a Christmas present in advance which I wish you would use to buy feed for the puppies.

Regarding the usual mix-up about Scottie, entitled “Where Is She?”—she finally appeared from under a boxcar in the neighborhood of Gramercy Park. So I am proceeding to forget her for a few months. She seemed happy out here and, as you say, has much more poise this year than during her lamentable career as the Belle of Baltimore. She listens to me more willingly. I remember Mark Twain saying, “At fourteen I thought I'd never seen such an awful ignoramus as my father was, but when I got to be twenty, I used to be astonished at how much the old man had learned in the interval.”

Three Comrades is almost finished. Joan Crawford is still slated for Pat, but you never can tell. In my version, Taylor has about three lines to her two—perhaps that will discourage her.

Will you do this for me? Go to the storage and find the box which contains my files and abstract file or files which probably contain important receipts, old income tax statements, etc.—not the correspondence file. You will know the one or ones that I mean—those that would seem to have most to do with current business. I should have taken it or them along. Also I want my scrapbooks—the big ones including Zelda's and the photograph books. This should make quite a sizable assortment, and I'd like the whole thing boxed and sent to me here collect. If they won't send it this way, let me know what the charges will be. I have just sent them a check for $99.00 which covers all bills to date, but maybe they have another statement for me and don't know where to send it.

I like it here very much. I hear the report of my salary has been terrifically exaggerated in Baltimore. Thought at first it was Scottie's doing but she denies it. I like the work which is occasionally creative—most often like fitting together a very interesting picture puzzle. I think I'm going to be good at it.

With affection always,

Scott Fitz

xxx. TO Ted Paramore

From Turnbull.

[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation ] [Culver City, California]

October 24, 1937

Dear Ted:

I'd intended to go into this Friday but time was too short. Also, hating controversy, I've decided after all to write it. At all events it must be discussed now.

First let me say that in the main I agree with your present angle, as opposed to your first “war” angle on the script, and I think you have cleared up a lot in the short time we've been working. Also I know we can work together even if we occasionally hurl about charges of pedantry and prudery.

But on the other hand I totally disagree with you as to the terms of our collaboration. We got off to a bad start and I think you are under certain misapprehensions founded more on my state of mind and body last Friday than upon the real situation. My script is in a general way approved of. There was not any question of taking it out of my hands—as in the case of Sheriff. The question was who I wanted to work with me on it and for how long. That was the entire question and it is not materially changed because I was temporarily off my balance.

At what point you decided you wanted to take the whole course of things in hand—whether because of that day or because when you read my script you liked it much less than did Joe 2 or the people in his office—where that point was I don't know. But it was apparent Saturday that you had and it is with my faculties quite clear and alert that I tell you I prefer to keep the responsibility for the script as a whole.

For a case in point: such matters as to whether to include the scene with Bruer in Pat's room, or the one about the whores in Bobby's apartment, or this bit of Ferdinand Grau's dialogue or that, or whether the car is called Heinrich or Ludwig, are not matters I will argue with you before Joe. I will yield points by the dozen but in the case of such matters, Joe's knowledge that they were in the book and that I did or did not choose to use them are tantamount to his acceptance of my taste. That there are a dozen ways of treating it all, or of selecting material, is a commonplace but I have done my exploring and made my choices according to my canons of taste. Joe's caution to you was not to spoil the Fitzgerald quality of the script. He did not merely say to let the good scenes alone—he meant that the quality of the script in its entirety pleased him (save the treatment of Koster). I feel that the quality was obtained in certain ways, that the scene of Pat in Bruer's room, for instance, has a value in suddenly and surprisingly leading the audience into a glimpse of Pat's world, a tail hanging right out of our circle of protagonists, if you will. I will make it less heavy but I can't and shouldn't be asked to defend it beyond that, nor is it your function to attack it before Joe unless a doubt is already in his mind. About the whores, again it is a feeling but, in spite of your current underestimation of my abilities, I think you would be overstepping your functions if you make a conference-room point of such a matter.

Point after point has become a matter you are going to “take to Joe,” more inessential details than I bothered him with in two months. What I want to take to Joe is simply this—the assurance that we can finish the script in three weeks more—you've had a full week to find your way around it—and the assurance that we are in agreement on the main points.

I'm not satisfied with the opening and can't believe now that Joe cared whether the airplane was blown up at the beginning or end of the scene, or even liked it very much—but except for that I think we do agree on the main line even to the sequences.

But, Ted, when you blandly informed me yesterday that you were going to write the whole thing over yourself, kindly including my best scenes, I knew we'd have to have this out. Whether the picture is in production in January or May there is no reason on God's earth why we can't finish this script in three to four weeks if we divide up the scenes and get together on the piecing together and technical revision. If you were called on this job in the capacity of complete rewriter then I'm getting deaf. I want to reconceive and rewrite my share of the weak scenes and I want your help but I am not going to spend hours of time and talent arguing with you as to whether I've chosen the best or second best speech of Lenz's to adorn the dressing-up scene. I am not referring to key speeches which are discussable but the idea of sitting by while you dredge through the book again as if it were Shakespeare—well, I didn't write four out of four best sellers or a hundred and fifty top-price short stories out of the mind of a temperamental child without taste or judgment.

This letter is sharp but a discussion might become more heated and less logical. Your job is to help me, not hinder me. Perhaps you'd let me know before we see Joe whether it is possible for us to get together on this.

This letter is an argument against arguments and certainly mustn't lead to one. Like you, I want to work.

[Scott]

Notes:

2 Joseph Mankiewicz, producer-director of Three Comrades.

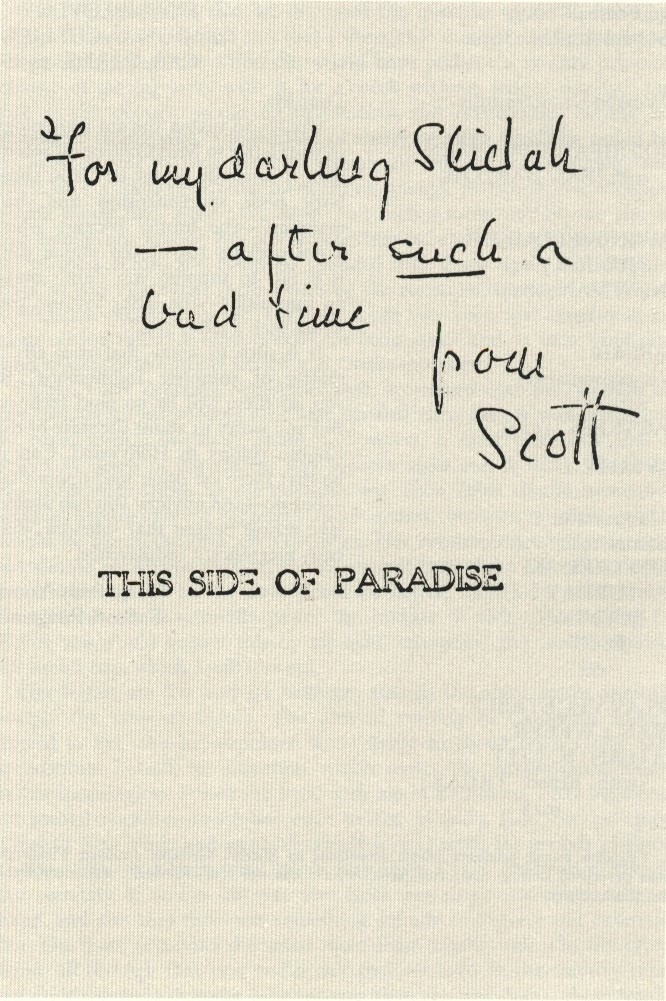

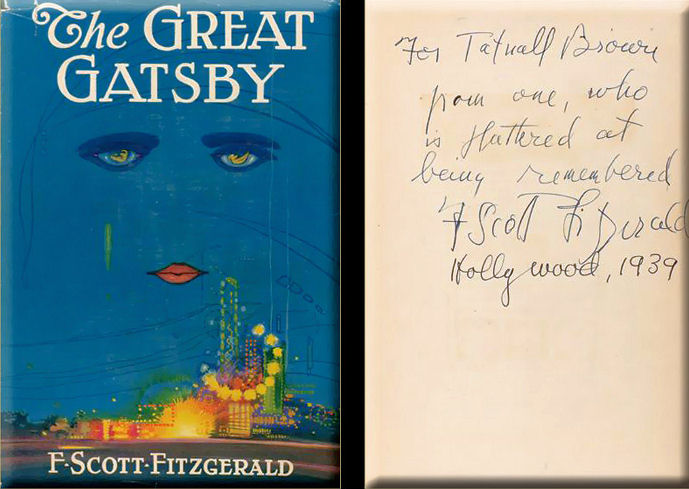

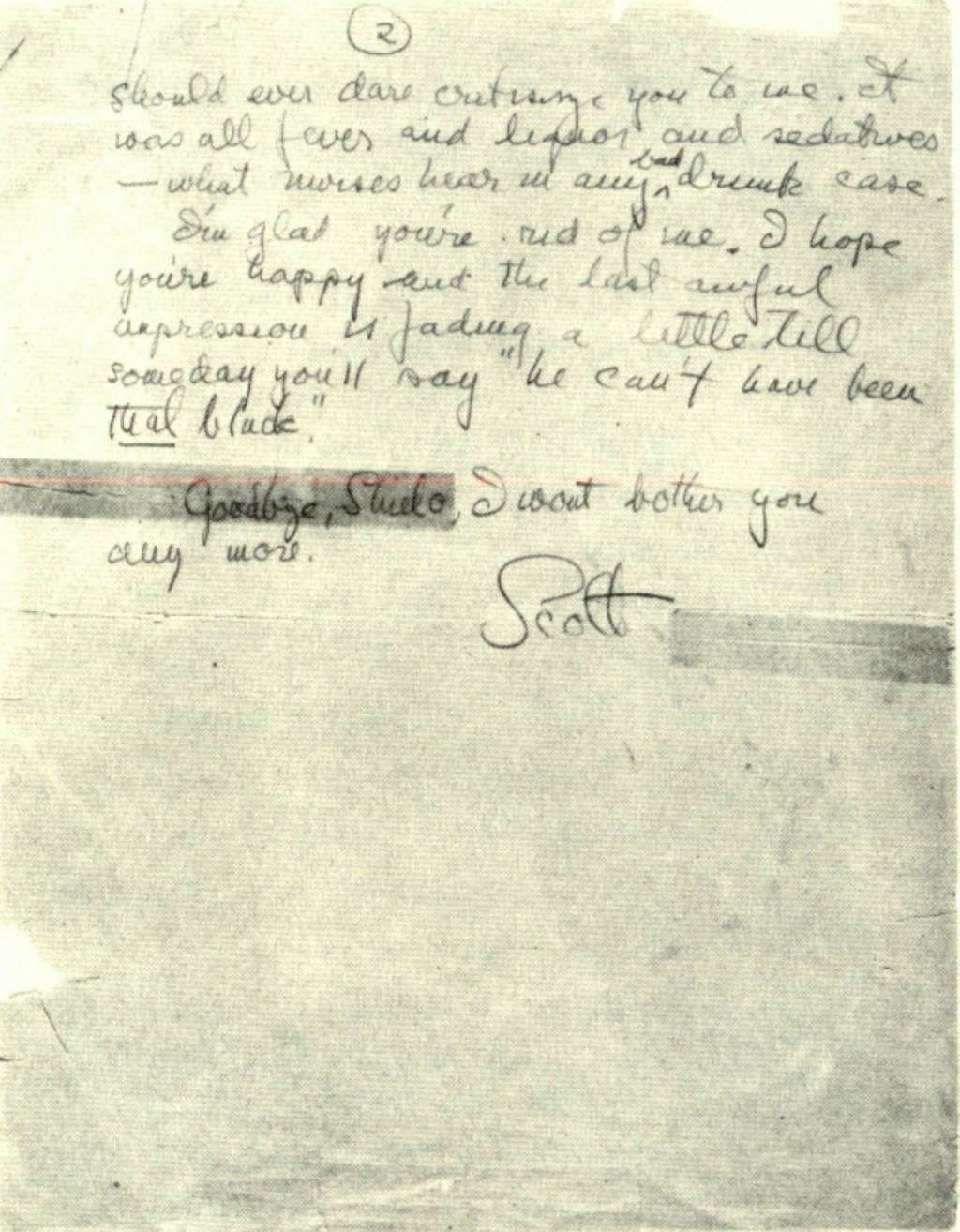

xxx. Inscription TO: Sheilah Graham

Inscription in This Side Of Paradise

For my darling Sheilah

—after such a bad time

From Scott

Fitzgerald inscribed this book for Sheilah Graham after an alcoholic episode in the fall of 1937 (Princeton University).

xxx. TO: Clayton Hutton

Late October 1937

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Hollywood, California

Ex-1st Lt. INFANTRY Headquarters Co. 1917

3d Football Team St Paul Academy 1910

Worked Unsuccessfully on REDHEADED WOMAN with JEAN HARLOW 1932

WON FIELDMEET (JUNIOR) NEWMAN school 1912

AFFAIR (unconsumated) with ACTRESS (1927)

WROTE 22 Unsuccessful Stories 1920. OFFERED TO SATURDAY EVENING POST ect

PLAY VEGETABLE RAN 2 WEEKS ATLANTIC CITY (with Ernest TRUAX) 1923

EX-EMPLOYEE BARON G COLLIER CAR CARDS, 1920

Dear Mr.

Unable to match the apt phrasology in your letter to Miss Graham of recent date, I can only repeat it: “You show both poor sportsmanship and bad manners"—the former because when a girl neglects two dozen phone calls it is fair to suppose you didn't make an impression—the latter because you wrote such a letter at all.

It is nice to know that it is all “a matter of complete indifference” to you, so there will be no hard feelings. But you worry us about the state of the English colony in Hollywood. Can it be that there are other telephones that—but no—and anyhow you can always take refuge behind that splendid, that truly magnificent indifference.

Very Truly Yours F. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

Clayton Hutton's attentions to Sheilah Graham annoyed Fitzgerald and prompted him to draft this letter, which was not sent. Hutton's stationery listed his productions.

xxx. TO: Drs. Robert S. Carroll and R. Burke Suitt

TL(CC), 2 pp. Princeton University

Hollywood, California

Oct. 22, 1937.

Dear Dr. Carroll or Dr. Suitt:

You will remember that we discussed the question of Zelda making a trip to Alabama by herself and that I thought it was out of the question—the reasons being that while she would have perhaps a seventy per cent chance of getting away with it for a week without serious damage, the risk, if she doesn't, would be tremendous and irrepairable. Having no judgment of any kind, a few drinks of sherry or a few highballs would be as liable as not to turn her into completely irresponsible channels, and there isn't a force in Montgomery strong enough to handle the situation which would then arise. Mrs. Sayer isn't such a force, nor anyone else in her family nor among her immediate friends, and it might lead to an awful mess before she could be rounded into shape again and brought back to you. After that there would be the consequent reaction of loss of confidence, melancholia etc. However, I am very keen that she should go there with a nurse—a nurse picked for being quiet and “a lady,” not one who would try to obtrude herself and “make things go.”

When I left Zelda on September 15th, we talked over the question of my making an intervening visit and decided then that it was better not to come until Christmas. There is, however, a faint possibility that I might fly down in November, stay for one night and fly back. However, that is problematical. So the question was when Zelda should spend her week in Montgomery. I suggested about midway between my visits, which would be about the fifth of November. Her counter-suggestion was that she should go Thanksgiving. I should suggest that if she now shows signs of restlessness, the former date would be better, though for sentimental reasons she would naturally prefer the holiday. I wish, after talking to Zelda, you would answer this by air mail, estimating the funds required for such a trip, which I will forward.

Her letters are few and far between, though the spirit seems approximately the same as before. The idea of coming to California doesn't appeal to her. She has expressed some desire to go off on her own and reconstitute herself, an intention which under the circumstance seems rather meaningless. When she lived with me in Baltimore, I left her alone on several occasions—sent her once to the World's Fair, two or three times to New York, and went off myself several times for periods of three or four days—but every time made sure there was a trustworthy friend, our secretary of whom she was very fond, her sister or mother close at hand, and also that there was something definite to distract and entertain her. On those occasions she acted more than usually well. On the other hand, all through that year and a half that we lived in the country (and we can't conclude that she is better now than she was then), there would be episodes of great gravity that seemed to have no “build up,” outbursts of temper, violence, rashness etc. that could neither be foreseen or forestalled. Now I assume that in shushing any desire of hers to walk right out into the world, we are entirely in accord.

Do write me how things progress. I suppose she has been moved to the other room according to our conversation.

Always sincerely and gratefully,

xxx. To Mrs. Bayard Turnbull

From Turnbull.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation Culver City, California

[Fall, 1937]

Dear Margaret:

I have owed you a letter for so long but these have been crowded months. I suppose Scottie told you the general line-up—after almost 3 years of intermittent illness it's nice to be on a steady job like this—a sort of tense crossword puzzle game, creative only when you want it to be, a surprisingly interesting intellectual exercise. You mustn't miss my first effort, Three Comrades, released next winter.

I'm sorry you were ill last March—a blood transfusion—that sounds serious! The news about Frances is strange and loyal and profound. I hope she finds it again—it's not very easy if you have “anything to you.” I know—though I've often tried desperately hard to be light of love.

Antony 1 is a fine book—odd I almost sent it to you! Also an odd comment—several people who were “tops” in English society—and I don't mean the fast set but the inner-of-inner Duke-of-York business—told me he was “rather a bounder.” I wonder what they meant—I can sort of understand.

I have sent Andrew two seats to Harvard-Princeton and two to Navy-Princeton. They will arrive in a few weeks addressed to me care of you with Princeton University Athletic Association stamped on the envelope. Just open them and send them to Andrew with my enduring affection.

And reserve a bushel for yourself.

Scott

Notes:

1 By James Lytton, Viscount Knebworth.

xxx. TO: Beatrice Dance

Postmarked 27 November 1937

ALS, 7 pp. Princeton University

Garden of Allah letterhead, Hollywood, California

Beatrice:

The confusion of my life is typified by the fact that it is over a month since you so sweetly remembered my birthday with the fine hankerchiefs. They were lovely as a snowfall. Won't you stop wringing my heart that way? This is said lightly but I was more touched than you know. Life + Fortune have become part of my life + my fortune but I think of you when the Postman puts them on the door step.

So much has happened, most of it at last in process of digestion for a new novel though I think I'll stay here another year + fully recoup my finances. I like it—everything awful about it you hear is true but it has a strange mercurial sort of life. Ive been working on a script of Three Comrades, a book that falls just short of the 1st rate (by Remarque)—it leans a little on Hemmingway + others but tells a lovely tragic story. It will be done presumably by Tracy, Taylor, Tone + Margaret Sullivan.

There have been alarms + excursions beside and a new point of view since the drinking finally fell away (it's been over a year now). Daughter came out with Helen Hayes and spent August under her chaperonage, living a sort of Alice-in-Wonderland life in the pools of the stars—just what any 15 year old would dream of. The talent scouts were after her but I shipped her back East to Miss Walkers. She did well on her Vassar exams + goes there in Sept—age 16. It is a choice between 2 evils, Hollywood or Yale + Princeton proms + I guess the second is the least threatening.

Zelda is no better—I took her to Charleston on a trip from the sanitarium in Sept + she held up well enough but there is always a gradual slipping. I've become hard there and don't feel the grief I did once—except sometimes at night or when I catch myself in some spiritual betrayal of the past.

The emotional life is healthier than for several years—a somewhat hectic affair in which Winchell spared me by simply calling me a “love-story novelist” and an amusing meeting with Ginevra King (Mitchell) the love of my youth. Ive seen old friends again, friends again with Ernest + Gerald Murphy + so many people who'd drifted away in my cloistered (or perhaps wolf's den) years. Here introspection melts away in the thin yellow air and at Palm Springs last week I felt as you must have at the Casa de Manana.1

Proust you'll love till the end + then you'll finish it from sheer intention—up to Le Prisonniere its fine + Albertine disparu picks up at the end but the last 3 volumes could have been revised with profit. Mice + Men has been praised all out of proportion to its merits. I hope you didn't read my recent Esquire stuff. It was all dictated when I had the broken shoulder + sounds like it.

San Antonio was hot when my train stopped there last July—of course I was tempted to call you up but of course didn't. Later with Scottie I spent a night in Juarez + El Paso + several times, waiting for planes I wandered about desolate breathless airports + thought of you + of how “Slinging Sammy Baugh” beat Southern Methodist—the only two events in Texas since the Alamo as far as I'm concerned.

I have two plays to be produced—one (a dramatization The Diamond as Big as the Ritz) in Pasadena this winter2 + also a play from Tender in New York this Spring I hope.3 My own play remains unfinished because of work here. Xmas I give Scottie her usual Baltimore party + spend Xmas with my invalid. And so it goes.

This is all egotistic news. From your letters I see a good deal but not as much as I would wish to. I do not feel as certain about anything as I did two years ago or I would be full of preachments—not that I doubt my judgements then but I feel something fermenting in me or the times that I can't express and I dont yet know what lights or how strong will be thrown on it. I don't know, even, whether I shall be the man to do it. Perhaps the talent, too long neglected, has passed its prime

Ever your Devoted Scott

Notes:

1 Nightclub at the Dallas Pan-American Exposition.

2 By an amateur group.

3 Not produced.

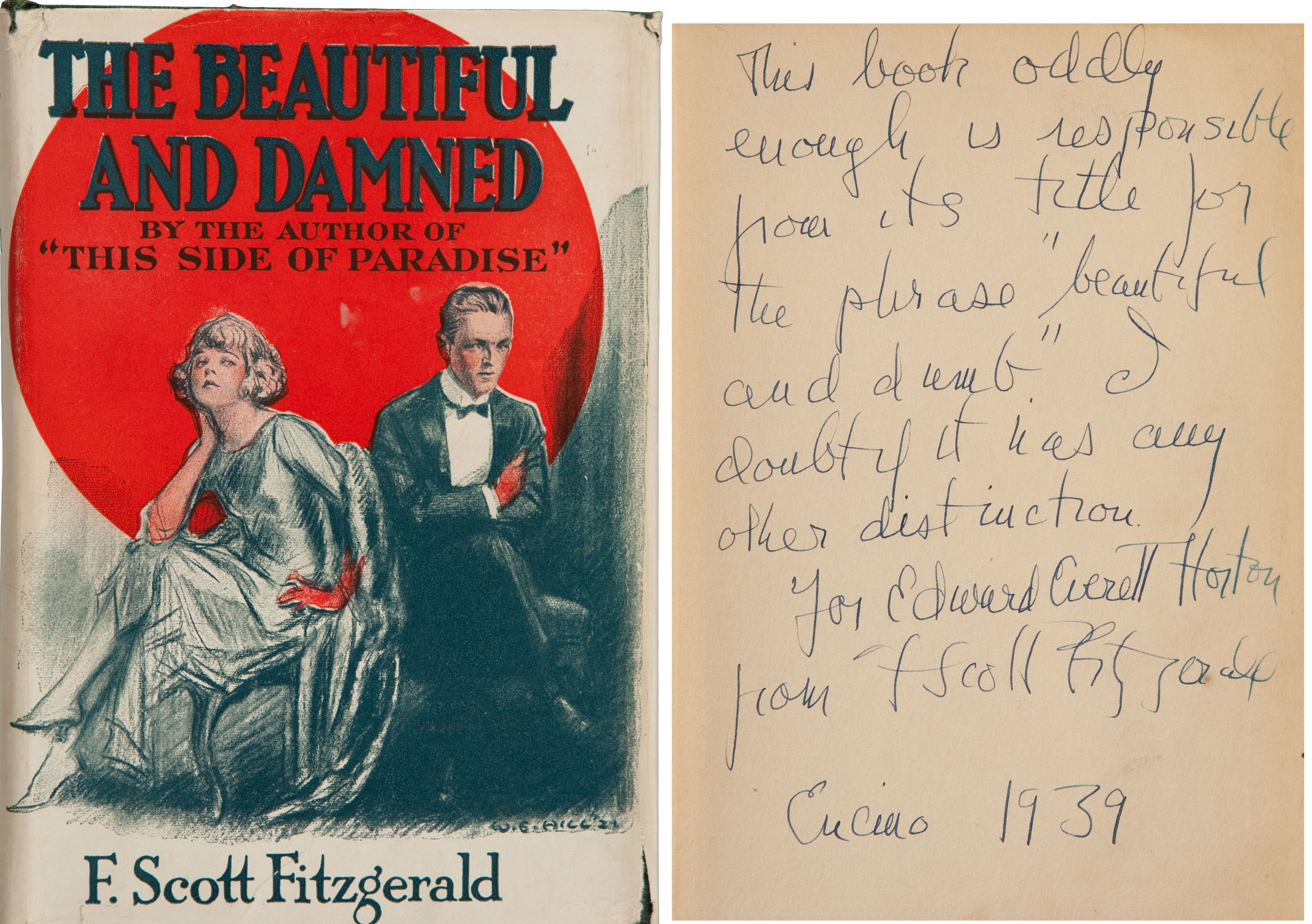

xxx. TO: Charles A. Post

TL, 2 pp. [This letter was signed for Fitzgerald], Western Reserve Historical Society

MGM letterhead. Culver City, California

Nov. 30, 1937.

Dear Mr. Post:

Hope this will be what you want: I was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, September 24th, 1896, the son of a broker, Edward Fitzgerald, who once wrote a novel with another young man, fortunately never published. My great-grandfather's brother, Francis Scott Key, wrote the “Star Spangled Banner,” and those were the only signs of literary activity in the family until I came along.

I was educated at the St. Paul Academy in St. Paul; Newman School, New Jersey; and Princeton University, where I wrote for the literary and humorous monthlies and composed musical comedies which were given by the Triangle Club. I was Lieutenant of Infantry during the World War and Aide-de-Camp to Brigadier General John A. Ryan, and when I reached the port of embarkation and was loaded up with gas masks, steel helmet and iron ration, the Germans decided they'd better quit. That's the true story of the armistice. Have ever since suffered from non-combatant shell-shock in the form of ferocious nightmares.

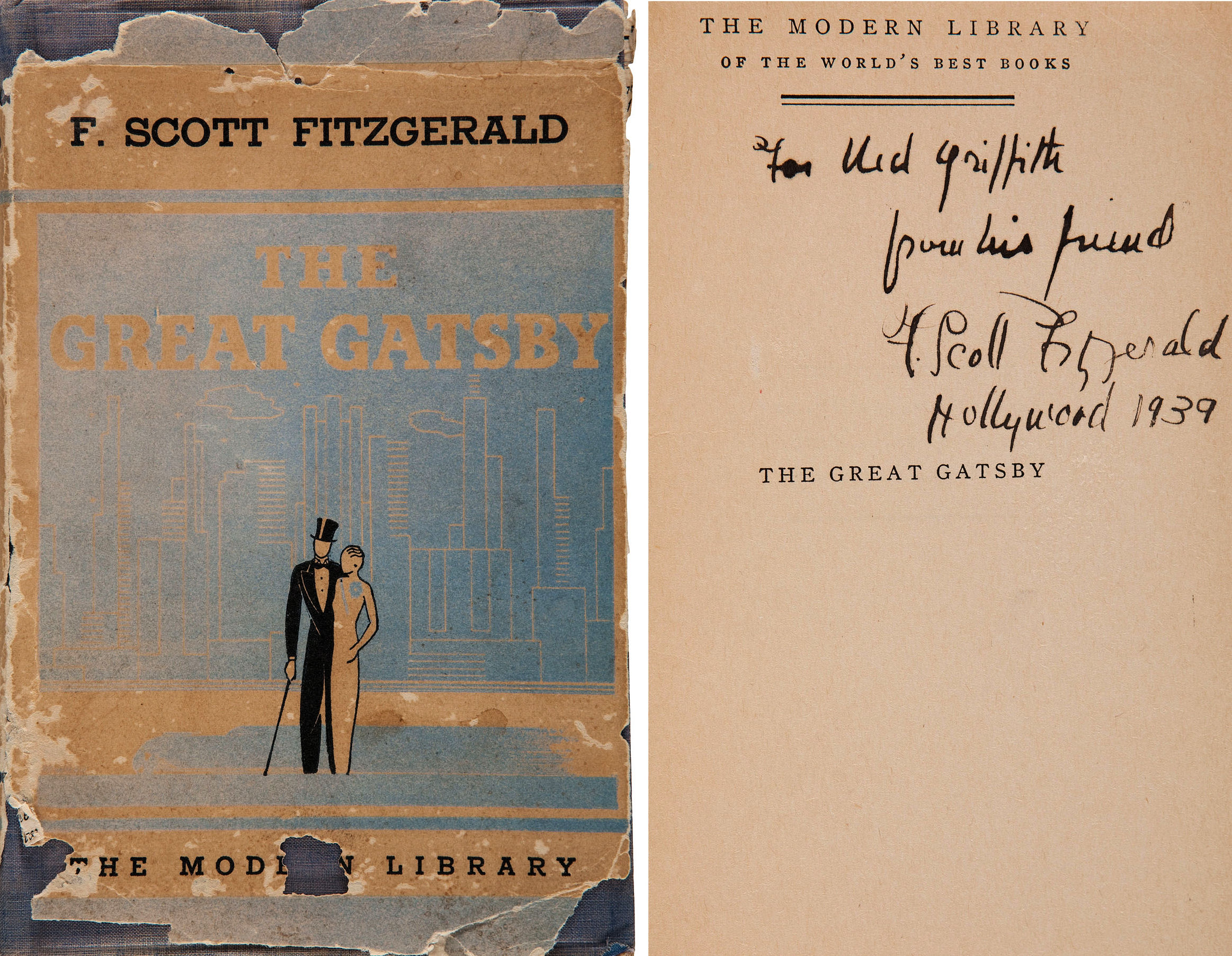

I became an advertising man for nine months and then a writer for life. Published THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, a novel, in 1920 at the age of twenty-three. This seemed to catch on and was followed by THE' BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, 1922, and THE GREAT GATSBY, 1925. Then after a long interval came TENDER IS THE NIGHT in 1934. Meanwhile I wrote about 150 short stories for the Saturday Evening Post, Scribners, American Mercury, Harpers, etc., about a third of which are collected into four books: FLAPPERS AND PHILOSOPHERS, 1920, TALES OF THE JAZZ AGE, 1922, ALL THE SAD YOUNG MEN, 1926, TAPS AT REVEILLE, 1935. At one point, 1923, I wrote a play, THE VEGETABLE, which was produced with Ernest Truax in Atlantic City, but it was such a dismal failure that it never reached New York. There have also been numerous articles and three trips to Hollywood, which is my present address. All in all very much the usual career of an American writer, even including the five years spent abroad as an expatriate.

I married, in 1920, Zelda Sayre, daughter of Judge A. D. Sayre of the Alabama Supreme Court, and have one daughter, Frances Scott Fitzgerald, born in 1921, preparing to enter Vassar next year. Most of what has happened to me is in my novels and short stories, that is, all the parts that could go into print.

My favorite American authors are Dreiser, Hemmingway and the early Gertrude Stein. I am an admirer of Mencken and Spencer Tracy, but not of Benny Goodman or Father Coughlin. I would like to be a G-Man but I'm afraid it is too late, like to swim, hate large parties and have insomnia. Like living in France, though New York is my favorite city.

Thanking you for your interest and apologizing for the unavoidable egotism of the above,

Sincerely,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

xxx. TO: Edwin Knopf

TL(CC), 1 p. Princeton University

Hollywood, California

Dec. 7, 1937

Dear Eddie:

Just received my notice about renewal and am delighted that you think I'm of use to you.1

I want to put in writing the one worry which you didn't think important yesterday. As I said, my play had for two acts a prison background which has since been overplayed by the release of ALCATRAZ, THE LAST GANGSTER and other pictures. When I get to it, which may be in three to six months, I want to rewrite it, preserving the plot and most of the characters but changing this element to another. So the element “institutional humanitarianism” which I supplied hastily for the contract in order to avoid divulging the plot, will be lacking from the new version.

My worry is only that my right to produce the play remain intact, especially if I should enlist a collaborator who would naturally want to know that my work in this regard is all free from strings or tails. I may add that I never had, nor have now, the faintest idea of finishing the piece on any but my own time, but the playwriting venture is of great importance to me in keeping my name known during this time when I will be behind the comparative anonymity of the screen. I know that in this regard my interests can in no way run contrary to yours.

Ever yours,

Notes:

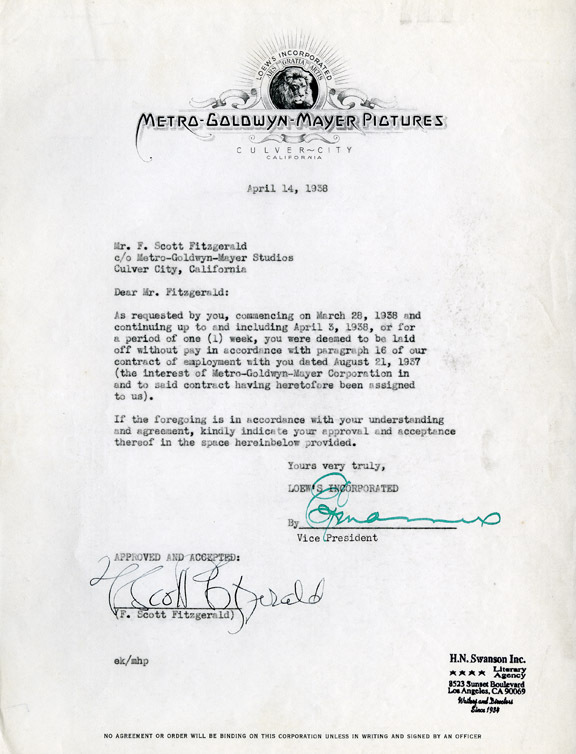

1 MGM had renewed Fitzgerald's contract for one year at $1,250 per week.

xxx. To Pete and Peggy Finney

[Telegram, undated (1937)] From The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 76, No. 3 (Spring 2015).

RESENT YOUR FUNCTIONING IN FITZGERALD CASE BUT CANT HELP BROTHERLY GREETINGS

SANTA CLAUS

xxx. To Pete and Peggy Finney

[Telegram, undated (1937)] From The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 76, No. 3 (Spring 2015).

SING HOTCHA CHA SING HEY HI NINNEY OR NEGRO SONG FROM OLD VIRGINY QUOTE FROM THE WORKS OF POPE OR PLINY SOME FRAGMENT NEITHER BRASH NOR TINNY SOUNDING A FINE AND CRYSTAL CLEAR WRAPTED UP IN CELLOPHANE NEW YEAR FOR PEGGY PETE AND PEACHES FINNEY

SCOTT FITZGERALD

1938

xxx. TO: Sheilah Graham

Early 1938(?)

ALS, 2 pp. [Numbered 2 and 2A; the first page is missing.], Princeton University

Hollywood, California

So glad it went well, my blessed. Will be back when you wake up in the very late afternoon

Scott

Second Note

I am here (it is 5:30) + you are getting rapidly out of the ether + very sick.2 You want to be anyhow. You asked me sweet questions and said you couldn't believe they did it while you were asleep. I love you + I am coming back in the morning quite early + sit with you. It has been a day for all of us + I must go eat + get a bit of sleep. Thank God it is over + youre well again

Scott

Notes:

2 Miss Graham had undergone surgery.

xxx. TO Eddie Mannix And Sam Katz

From Turnbull.

[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation] [Culver City, California]

[Winter, 1938]

Dear Sirs:

I have long finished my part in the making of Three Comrades but Mank——2 has told me what the exhibitors are saying about the ending and I can't resist a last word. If they had pronounced on Captains Courageous at this stage, I feel they would have had Manuel the Portuguese live and go out West with the little boy and Captains Courageous could have stood that much better than Three Comrades can stand an essential change in its story. In writing over a hundred and fifty stories for George Lorimer, the great editor of The Saturday Evening Post, I found he made a sharp distinction between a sordid tragedy and a heroic tragedy—hating the former but accepting the latter as an essential and interesting part of life.

I think in Three Comrades we run the danger of having the wrong head go on the right body—a thing that confuses and depresses everyone except the ten-year-olds who are so confused anyhow that I can't believe they make or break a picture. To every reviewer or teacher in America, the idea of the comrades going back into the fight in the spirit of “My head is bloody but unbowed” is infinitely stronger and more cheerful than that they should be quitting—all the fine talk, the death of their friends and countrymen in vain. All right, they were suckers, but they were always that in one sense and if it was despicable what was the use of telling their story?

The public will feel this—they feel what they can't express—otherwise we'd change our conception of Chinese palaces and French scientists to fit the conception of hillbillies who've never seen palaces or scientists. The public will be vaguely confused by the confusion in our mind—they'll know that the beginning and end don't fit together and when one is confused one rebels by kicking the thing altogether out of mind. Certainly this step of putting in the “new life” thought will not please or fool anyone—it simply loses us the press and takes out of the picture the real rhythm of the ending which is:

The march of four people, living and dead, heroic and inconquerable, side by side back into the fight.

Very sincerely yours,

[F. Scott Fitzgerald]

Notes:

2 Joseph Mankiewicz.

xxx. TO Mrs. Edwin Jarrett

From Turnbull.

[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation] [Culver City, California]

February 17, 1938

Dear Mrs. Jarrett:

The play pleases me immensely. So faithful has been your following of my intentions that my only fear is that you have been too loyal. I hope you haven't—I hope that a measure of the novel's intention can be crammed into the two hours of the play. My thanks, hopes and wishes are entirely with you—it pleases me in a manner that the acting version of The Great Gatsby did not. And I want especially to congratulate you and Miss Oglebay on the multiple feats of ingenuity with which you've handled the difficult geography and chronology so that it has a unity which, God help me, I wasn't able to give it.

My first intention was to go through it and “criticize” it, but I see I'm not capable of doing that—too many obstacles in my own mind prevent me from getting a clear vision. I had some notes—that Rosemary wouldn't express her distaste for the battlefield trip—she had a good time and it belittles Dick's power of making things fun. Also a note that Dick's curiosity and interest in people was real—he didn't stare at them—he glanced at them and felt them. I don't know what point of the play I was referring to. Also I'm afraid some of his long Shavian speeches won't play—and no one's sorrier than I am—his comment on the battle of the Somme for instance. Also Tommy seemed to me less integrated than he should be. He was Tommy Hitchcock in a way whose whole life is a challenge—who is only interested in realities, his kind—in going into him you've brought him into the boudoir a little—I should be careful of what he says and does unless you can feel the strong fresh-air current in him. I realize you've had to use some of the lesser characters for plot transitions and convenience, but when any of them go out of character I necessarily feel it, so I am a poor critic. I know the important thing is to put over Dick in his relation to Nicole and Rosemary and, if you can, Bob Montgomery and others here would love to play the part. But it must get by Broadway first.

If it has to be cut, the children will probably come out. On the stage they will seem to press, too much for taste, against distasteful events. As if Dick had let them in for it—he is after all a sort of superman, an approximation of the hero seen in overcivilized terms—taste is no substitute for vitality but in the book it has to do duty for it. It is one of the points on which he must never show weakness as Siegfried could never show physical fear. I did not manage, I think in retrospect, to give Dick the cohesion I aimed at, but in your dramatic interpretation I beg you to guard me from the exposal of this. I wonder what the hell the first actor who played Hamlet thought of the part? I can hear him say, “The guy's a nut, isn't he?” (We can always find great consolation in Shakespeare.)

Also to return to the criticism I was not going to make—I find in writing for a particular screen character here that it's convenient to suggest the way it's played, especially the timing—i.e., at the top of page 25 it would probably be more effective—

Rosemary didn't grow up. (pause) It's better that way. (pause) Etc.

But I'd better return to my thesis. You've done a fine dramatization and my gratitude to you is part of the old emotion I put into the book, part of my life.

Most sincerely,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

xxx. TO: Joseph Mankiewicz

CC, 3 pp. Princeton University

New York City

January 17, 1938.

Dear Joe:

I read the third batch (to page 51) with mixed feelings. Competent it certainly is, and in many ways tighter knit than before. But my own type of writing doesn’t survive being written over so thoroughly and there are certain pages out of which the rhythm has vanished. I know you don’t believe the Hollywood theory that the actors will somehow “play it into shape,” but I think that sometimes you’ve changed without improving.

P. 32 The shortening is good.

P. 33 “Tough but sentimental.” Isn’t it rather elementary to have one character describe another? No audience heeds it unless it’s a false plant.

P. 33 Pat’s line “I would etc.,” isn’t good. The thing isn’t supposed to provoke a sneer at Alons. The pleasant amusement of the other is much more to our purpose. In the other she was natural and quick. Here she’s a kidder from Park Avenue. And Erich’s “We’re in for it etc.,” carries the joke to its death. I think those two lines about it in midpage should be cut. Also the repeat on next page.

P. 36 Original form of “threw it away like an old shoe” has humor and a reaction from Pat. Why lose it? For the rest I like your cuts here.

P. 37 The war remark from Pat is as a chestnut to those who were in it—and meaningless to the younger people. In 8 years in Europe I found few people who talked that way. The war became rather like a dream and Pat’s speech is a false note.

P. 39 I thought she was worried about Breur—not her T.B. If so, this paragraph (the 2nd) is now misplaced.

P. 41 I liked Pat’s lie about being feverish. People never blame women for social lies. It makes her more attractive taking the trouble to let him down gently.

P. 42 Again Pat’s speech beginning “—if all I had” etc., isn’t as good as the original. People don’t begin all sentences with and, but, for and if, do they? They simply break a thought in mid-paragraph, and in both Gatsby and Farewell to Arms the dialogue tends that way. Sticking in conjunctions makes a monotonous smoothness.

The next scene is all much much better but—

P. 46 Erich’s speech too long at beginning. Erich’s line about the bad smell spoils her line about spring smell.

P. 48 “Munchausen” is trite. Erich’s speech—this repetition from first scene is distinctly self-pity.

I wired you about the flower scene. I remember when I wrote it, thinking whether it was a double love climax, and deciding it wasn’t. The best test is that on the first couple of readings of my script you didn’t think so either. It may not be George Pierce Baker but it’s right instinctively and I’m all for restoring it. I honestly don’t mind when a scene of mine is cut but I think this one is terribly missed.

P. 49 Word “gunman” too American. Also “tried to strong-arm Riebling” would be a less obvious plant.

P. 51 Koster’s tag not right. Suppose they both say, with different meanings, “You see?”

What I haven’t mentioned, I think is distinctly improved.

New York is lousy this time of year.

Best always,

Notes:

Professor of playwriting, Harvard and Yale.

xxx. TO: Joseph Mankiewicz

CC, 4 pp. Princeton University

MGM stationery. Culver City, California

January 20, 1938

Dear Joe:

Well, I read the last part and I feel like a good many writers must have felt in the past. I gave you a drawing and you simply took a box of chalk and touched it up. Pat has now become a sentimental girl from Brooklyn, and I guess all these years I’ve been kidding myself about being a good writer.

Most of the movement is gone—action that was unexpected and diverting is slowed down to a key that will disturb nobody—and now they can focus directly on Pat’s death, squirming slightly as they wait for the other picture on the programme.

To say I’m disillusioned is putting it mildly. For nineteen years, with two years out for sickness, I’ve written best-selling entertainment, and my dialogue is supposedly right up at the top. But I learn from the script that you’ve suddenly decided that it isn’t good dialogue and you can take a few hours off and do much better.

I think you now have a flop on your hands—as thoroughly naive as “The Bride Wore Red” but utterly inexcusable because this time you had something and you have arbitrarily and carelessly torn it to pieces. To take out the manicurist and the balcony scene and then have space to put in that utter drool out of True Romances which Pat gets off on page 116 makes me think we don’t talk the same language. God and “cool lip”s, whatever they are, and lightning and elephantine play on words. The audience’s feeling will be “Oh, go on and die.” If Ted had written that scene you’d laugh it out of the window.

You are simply tired of the best scenes because you’ve read them too much and, having dropped the pilot, you’re having the aforesaid pleasure of a child with a box of chalk. You are or have been a good writer, but this is a job you will be ashamed of before it’s over. The little fluttering life of what’s left of my lines and situations won’t save the picture.

Example number 3000 is taking out the piano scene between Pat and Koster and substituting garage hammering. Pat the girl who hangs around the garage! And the re-casting of lines—I feel somewhat outraged.

Lenz and Bobby’s scene on page 62 isn’t even in the same category with my scene. It’s dull and solemn, and Koster on page 44 is as uninteresting a plodder as I’ve avoided in a long life.

What does scene 116 mean? I can just hear the boys relaxing from tension and giving a cheer.

And Pat on page 72—“books and music—she’s going to teach him.” My God, Joe, you must see what you’ve done. This isn’t Pat—it’s a graduate of Pomona College or one of more bespectacled ladies in Mrs. Farrow’s department. Books and music! Think, man! Pat is a lady—a cultured European—a charming woman. And Bobby playing soldier. And Pat’s really re-fined talk about the flower garden. They do everything but play ringaround-a-rosie on their Staten Island honeymoon. Recognizable characters they simply are not, and cutting the worst lines here and there isn’t going to restore what you’ve destroyed. It’s all so inconsistent. I thought we’d decided long ago what we wanted Pat to be!

On page 74 we meet Mr. Sheriff again, and they say just the cutest merriest things and keep each other in gales of girlish laughter.

On page 93 God begins to come into the script with a vengeance, but to say in detail what I think of these lines would take a book. The last pages that everyone liked begin to creak from 116 on, and when I finished there were tears in my eyes, but not for Pat—for Margaret Sullavan.

My only hope is that you will have a moment of clear thinking. That you’ll ask some intelligent and disinterested person to look at the two scripts. Some honest thinking would be much more valuable to the enterprise right now than an effort to convince people you’ve improved it. I am utterly miserable at seeing months of work and thought negated in one hasty week. I hope you’re big enough to take this letter as it’s meant—a desperate plea to restore the dialogue to its former quality—to put back the flower cart, the piano-moving, the balcony, the manicure girl—all those touches that were both natural and new. Oh, Joe, can’t producers ever be wrong? I’m a good writer—honest. I thought you were going to play fair. Joan Crawford might as well play the part now, for the thing is as groggy with sentimentality as “The Bride Wore Red”, but the true emotion is gone.

Notes:

Fitzgerald’s original screenplay for Three Comrades was published in 1978.

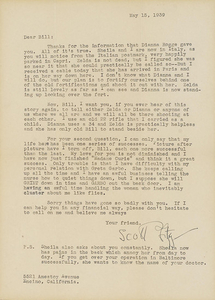

xxx. To William Hodapp

February 8, 1938, and unknown, 1938

Two letters collection, comprising the following:

(1) ALS, undated, 6 pp, in pencil, signed "Scott Fitzgerald." Comprising numerous edits to Hodapp's original script and commentary regarding Fitzgerald's opinion of the original and adapted piece.

(2) TLS, 1 p., on Metro Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. letterhead, signed "Scott Fitzgerald" to "Bill Hodapp," dated February 8, 1938. Fitzgerald informs Hodapp of the poor reception of the first production of "Diamond As Big As the Ritz" at the Pasadena Playhouse. He states:

"I wish I could give you better news. Again, this lightness I felt was no fault of your dramatization but a skimpiness inherent in the novelette. Perhaps another production in some professional hands would leave a different story to tell. What are your plans for it next?"

Notes:

Hodapp's dramatization of Diamond As Big as the Ritz, or, as Fitzgerald refers to it, "the Hodapptation," would see a second running on television during the Kraft Television Theatre, January 28, 1955 (Season 9, Episode 1). The accompanying pages of notes, which go into great detail concerning Fitzgerald's opinion on the story and his own writing style, were meant to enhance the theatre production and were the first draft of what would be the first theatre production.

xxx. TO Roger Garis

From Turnbull.

[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation] [Culver City, California]

February 22, 1938

Dear Mr. Garis:

In several ways, I am familiar with the melancholia you describe. Myself, I had what amounted to a nervous breakdown which never, however, approached psychosis. My wife, on the contrary, has been a mental patient off and on for seven years and will never be entirely well again, so I have a very detached point of view on the subject.

As I look at my own approach toward a practical inability to function and my gradual recession from it, it appears to me as being a matter of adjustment. The things that were the matter with me were so apparent, however, that I did not even need a psychoanalyst to tell me that I was being stubborn about this (giving up drink) or stupid about that (trying to do too many things); and so, to say that all such times of depression are merely “a moment of adjustment” is pretty easy.