F. Scott Fitzgerald's Life In Letters

The Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald

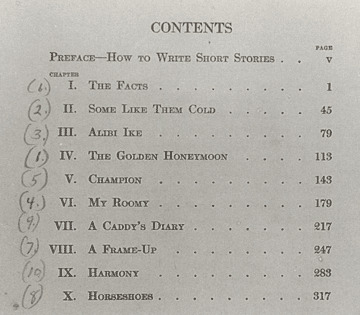

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: 1907–1919

Chapter 2: 1919–1924

Chapter 3: 1924–1930

Chapter 4: 1930–1937

Chapter 5: 1937–1940

Chapter 4: Summer 1930 – July 1937

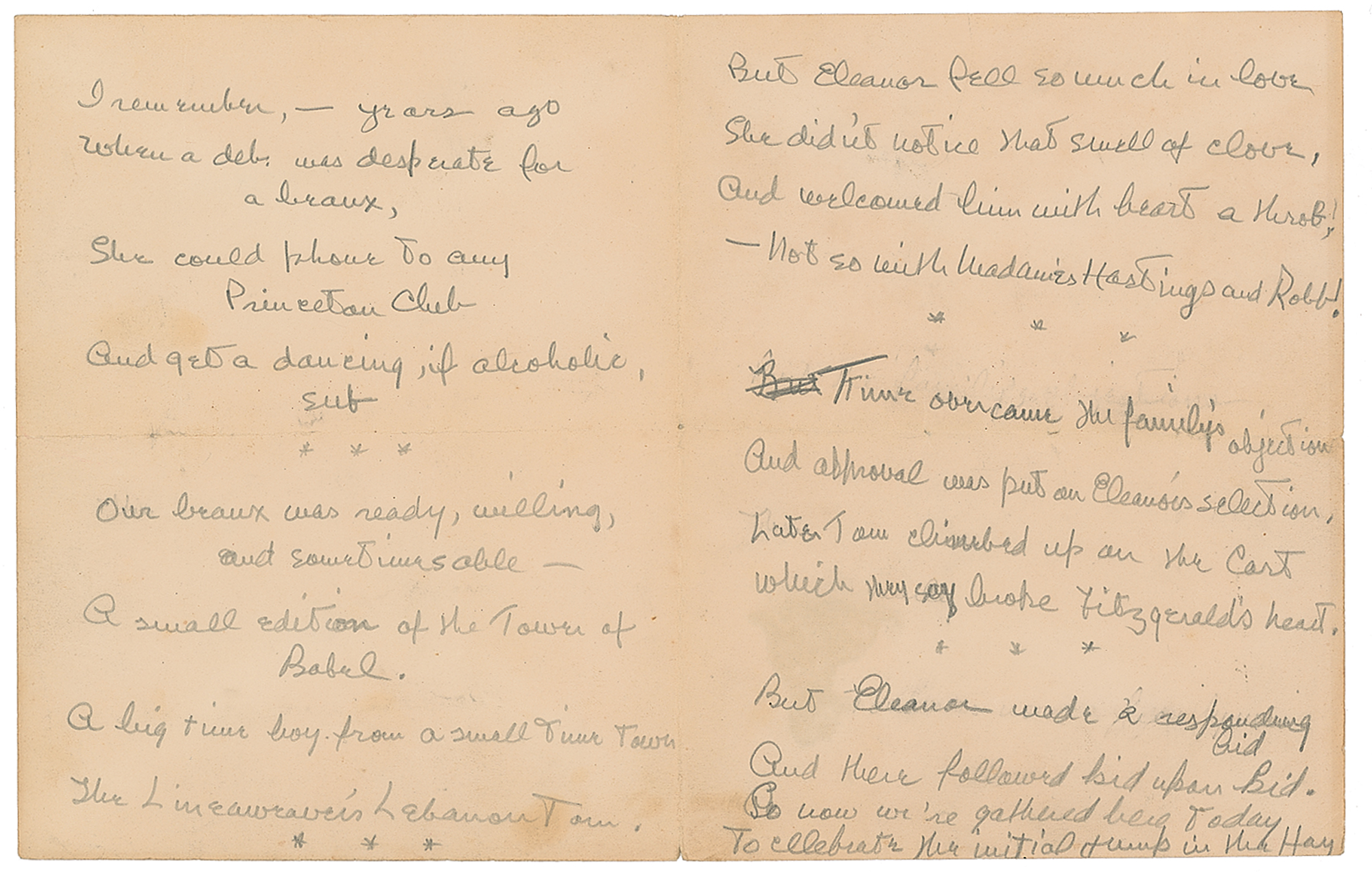

xxx. TO: Rosalind Sayre Smith

After 8 June 1930

AL (draft), 2 pp. Princeton University

Paris or Lausanne

Dear Rosalind

After three agonizing months in which I've given all my waking + most of my sleeping time to pull Zelda out of this mess, which itself arrived like a thunderclap. I feel that your letter which arrived today was scarcely nessessary. The matter is terrible enough without your writing me that you wish she would die now rather than go back to the mad world you and she have created for yourselves.” I know you dislike me, I know your ineradicable impression of the life that Zelda and I led, and evident your dismissal of any of the effort, and struggle success or happiness in it and I understand also your real feeling for her—but I have got Zelda + Scotty to take care of now as ever and I simply cannot be upset and harrowed still further. Also that since the Sayres can't come over and that Zelda can't for the moment go to America, I beg you to think twice before you say more to them than I have said. That is your business of course but our interests in this matter should be the same. Zelda at this moment is in no immediate danger—and I have promised to let you know as I already have if anything crucial is in the air.

****

I had collapsed in that fashion and Zelda were here taking every care of me imagine the effect on Zelda of recieving such a letter from my sister in America

xxx. TO: Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald

June 1930

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Beau-Rivage Palace stationery.

Ouchy-Lausanne, Switzerland

Adress Paris

Dear Mother:

My delay in writing is due to the fact that Zelda has been desperately ill with a complete nervous breakdown and is in a sanitarium near here. She is better now but recovery will take a long time I did not tell her parents the seriousness of it so say nothing—the danger was to her sanity rather than her life.

Scotty is in the appartment in Paris with her governess. She loved the picture of her cousins. Tell Father I visited the

“—seven pillars of Gothic mould in

Chillon’s dungeons deep and old,”

+ thought of the first poem I ever heard, or was “The Raven.” Thank you for the Chesterton.

Love

Scott

Notes:

From “The Prisoner of Chillon,” by Byron.

xxx. TO: Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald

June 1930

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Montreux, Switzerland

Dear Mother:

I’ve thought of you both a lot lately and I hope Father is better after his indigestion. Zelda’s recovery is slow. Now she has terrible ecxema—one of those mild but terrible diseases that don’t worry relations but are a living hell for the patient. If all goes as well as it did up to a fortnight ago we will be home by Thanksgiving.

According to your poem I am destined to be a failure. I re-enclose it

(1) All big men have spent money freely. I hate avarice or even caution

(2) I have never forgiven or forgotten an injury

(3) This is the only one that makes sense.

(4) If its worth doing. Otherwise it should be thrown over immediately

(5) No man’s critisism has ever been worth a damn to me.

These would be good rules for a man who wanted to be a chief clerk at 50.

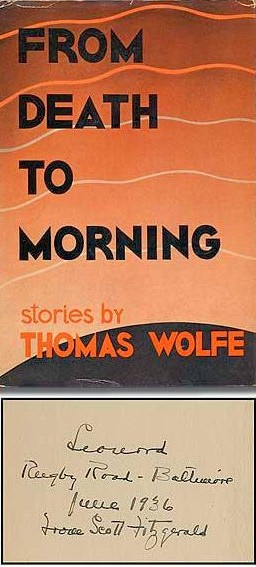

Thanks for the check but really you mustn’t. I re-enclose it. The snap I’ll send to Scotty. The children are charming. Adress me care of my Paris Bank though I’m still by father’s Castle of Chillon. Have you read Maurois’ Life of Byron? And Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel?

Much love to you both

Scott

Notes:

Andre Maurois, Byron (1930).

Look Homeward, Angel had been published by Scribners in 1929.

xxx. TO: Madame Lubov Egorova

CC, 2 pp. [Fitzgerald a French translation of his letter; the text was translated by Eric Roman], Princeton University

HOTEL RIGHI VAUDOIS, GLION

June 22, 1930

Dear Madame Egarowa,

Zelda is still very ill. From time to time there is some improvement and then all of a sudden she commits some insane act. Unfortunately, complete recovery seems to be still far away.

As you know, one of the things which prevents her from getting better, and goes against all of the doctors’ efforts, is her continuous fear that she is wasting time required for her dancing class and that she has no time to lose. This fear makes her nervous and unsettled, and it postpones her recovery every time she thinks about it. It is for this reason that she left Malmaison much too soon.

It is doubtful—though she is unaware of it—that she could ever return to her dancing school; in any event, she will never be able to work with the same intensity, even though to my mind her appearing on stage could do her a lot of good.

Moreover, doctors would like to know what her chances were, what her future was like as a dancer, when she fell ill. She does not know it herself: one minute she says one thing, the next another. Her situation being critical, it is rather necessary that she should know the answer, despite all the disappointment it could cause her. That is why, knowing the affection you bear her and all the interest that you take in her ambitions I have come to ask you for a frank opinion.

It may be that in answering the following questions we would succeed in finding a solution.

1.- Could she ever reach the level of a first-rate dancer?

2.- Will she ever be a dancer like Nikitina, Danilowa etc.?

3.- If the answer to question number 2 is yes, then how many years would be required for her to achieve this goal, based on the progress she was making?

4.- If the answer to question number 2 is no, then do you believe that through the charm of her face and that of her beautiful body she could manage to get important roles in ballets such as Massine, for example, produces in New York?

5.- Are there things such as balance, etc. that she will never achieve because of her age and because she started too late?

6.- Is she as good a dancer as “Galla,” for example? To give me an idea of her position in your school, are there many students who are better than she?

7.- On the whole, do you believe that if she had not taken ill, she could have achieved a level as a dancer that would have satisfied both her ideal and her ambitions?

Have you ever thought that, lately, Zelda was working too much for someone her age?

I understand that all these questions are importunate but the goal of this is to save her sanity, and the truth about her career is necessary. You are the only person whom I can ask because you have always been very good to my wife, and you have always been interested in her work.

With all my apologies for the bother I may cause you, please rest assured of my admiration and of my respectful feelings.

Notes:

On July 9, 1930, Egorova replied that Zelda would never be a first-rate dancer because she had started too late. Egorova added that Zelda could become a good to very good dancer and that she would be capable of dancing important roles in the Massine Ballet Company.

xxx. TO: Dr. Oscar Forel

AL (draft), 6 pp. [Italics in this draft represent passages underlined by Fitzgerald for emphasis], Princeton University

Summer(?) 1930

Lausanne, Switzerland (?)

For translation with carbon. But not on hotel stationary.

This letter is about a matter that had best be considered frankly now than six months or a year from now. When I last saw you I was almost as broken as my wife by months of horror. The only important thing in my life was that she should be saved from madness or death. Now that, due to your tireless intelligence and interest, there is a time in sight where Zelda and I may renew our life together on a decent basis, a thing which I desire with all my heart, there are other considerations due to my nessessities as a worker and to my very existence that I must put before you.

During my young manhood for seven years I worked extremely hard, in six years bringing myself by tireless literary self-discipline to a position of unquestioned preeminence among younger American writers, also by additional “hack-work” for the cinema ect. I gave my wife a comfortable and luxurious life such as few European writers ever achieve. My work is done on coffee, coffee and more coffee, never on alcohol. At the end of five or six hours I get up from my desk white and trembling and with a steady burn in my stomach, to go to dinner. Doubtless a certain irritability developed in those years, an inability to be gay which my wife—who had never tried to use her talents and intelligence—was not inclined to condone. It was on our coming to Europe in 1924 and apon her urging that I began to look forward to wine at dinner—she took it at lunch, I did not. We went on hard drinking parties together sometimes but the regular use of wine and apperatives was something that I dreaded but she encouraged because she found I was more cheerful then and allowed her to drink more. The ballet idea was something I inaugurated in 1927 to stop her idle drinking after she had already so lost herself in it as to make suicidal attempts. Since then I have drunk more, from unhappiness, and she less, because of her physical work—that is another story.

Two years ago in America I noticed that when we stopped all drinking for three weeks or so, which happened many times, I immediately had dark circles under my eyes, was listless and disinclined to work.

I gave up strong cigarettes and, in a panic that perhaps I was just giving out, applied for a large insurance policy. The one trouble was low blood-pressure, a matter which they finally condoned, and they issued me the policy. I found that a moderate amount of wine, a pint at each meal made all the difference in how I felt. When that was available the dark circles disappeared, the coffee didn't give me excema or beat in my head all night, I looked forward to my dinner instead of staring at it, and life didn't seem a hopeless grind to support a woman whose tastes were daily diverging from mine. She no longer read or thought or knew anything or liked anyone except dancers and their cheap satellites People respected her because I concealed her weaknesses, and because of a certain complete fearlessness and honesty that she has never lost, but she was becoming more and more an egotist and a bore. Wine was almost a nessessity for me to be able to stand her long monalogues about ballet steps, alternating with a glazed eye toward any civilized conversation whatsoever

Now when that old question comes up again as to which of two people is worth preserving, I, thinking of my ambitions once so nearly achieved of being part of English literature, of my child, even of Zelda in the matter of providing for her—must perforce consider myself first. I say that without defiance but simply knowing the limits of what I can do. To stop drinking entirely for six months and see what happens, even to continue the experiment thereafter if successful—only a pig would refuse to do that. Give up strong drink permanently I will. Bind myself to forswear wine forever I cannot. My vision of the world at its brightest is such that life without the use of its amentities is impossible. I have lived hard and ruined the essential innocense in myself that could make it that possible, and the fact that I have abused liquor is something to be paid for with suffering and death perhaps but not with renunciation. For me it would be as illogical as permanently giving up sex because I caught a disease (which I hasten to assure you I never have) I cannot consider one pint of wine at the days end as anything but one of the rights of man.

Does this sound like a long polemic composed of childish stubborness and ingratitude? If it were that it would be so much easier to make promises. What I gave up for Zelda was women and it wasn't easy in the position my success gave me—what pleasure I got from comradeship she has pretty well ruined by dragging me of all people into her homosexual obsession. Is there not a certain disingenuousness in her wanting me to give up all alcohol? Would not that justify her conduct completely to herself and prove to her relatives, and our friends that it was my drinking that had caused this calamity, and that I thereby admitted it? Wouldn't she finally get to believe herself that she had consented to “take me back” only if I stopped drinking? I could only be silent. And any human value I might have would disappear if I condemned myself to a life long ascetisim to which I am not adapted either by habit, temperment or the circumstances of my metier.

That is my case about the future, a case which I have never stated to you before when her problem needed your entire consideration. I want very much to see you before I see her. And please disassociate this letter from what I shall always feel in signing myself

Yours with Eternal Gratitude and Admiration

FIN

xxx. TO: Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald

1930

ALS, l p. Princeton University

Lausanne, Switzerland

Dear Mother

No news. I'm still here waiting. Zelda is better but very slowly. She can't cross the ocean for some time yet + it'll be a year before she can resume her normal life unless there's a change for the better. Adress me Paris, care of Guaranty. Actually I'm in Lausanne + migrate to Paris once a fortnight to see Scotty who has a small apartment. So we're all split up.

Got the Swiss book. Its no good.

Love to you both Scott

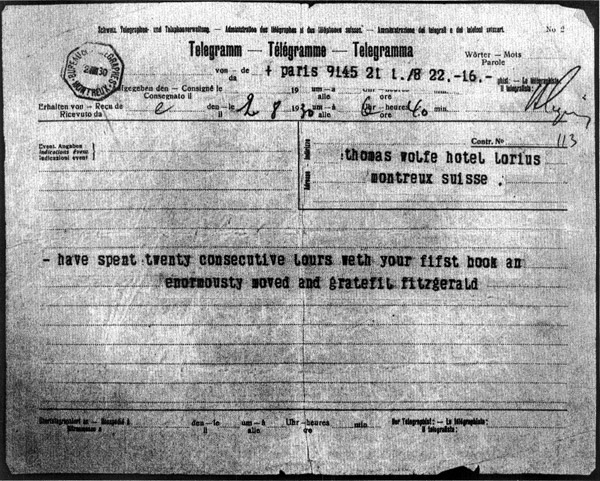

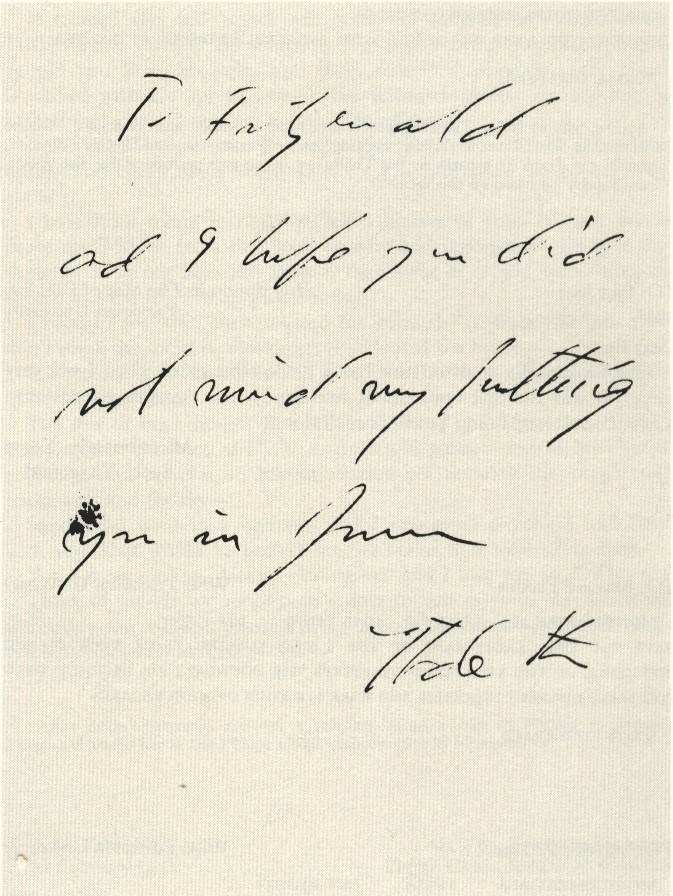

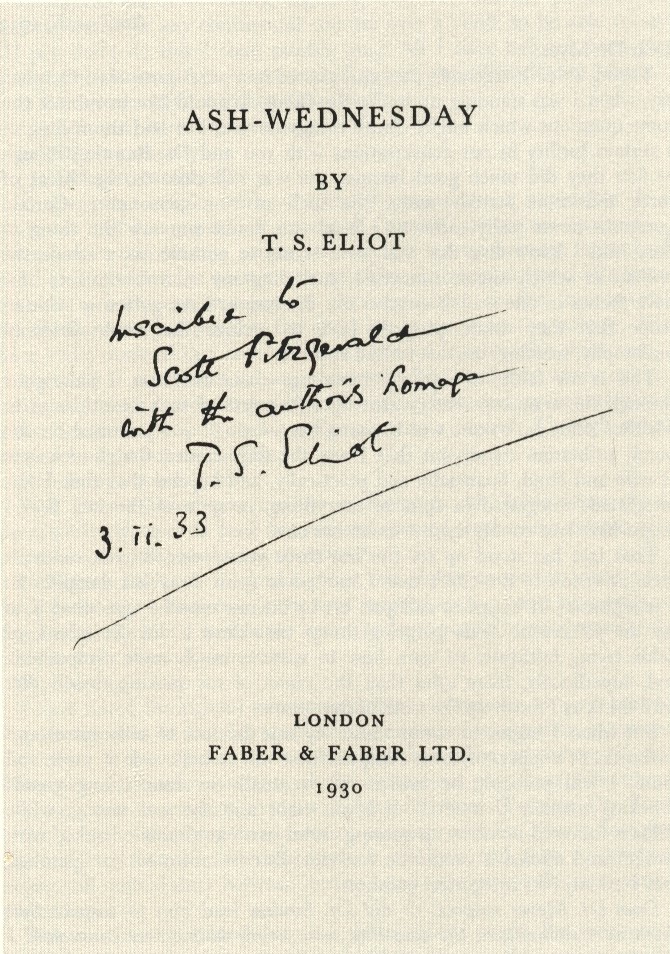

xxx. TO: Thomas Wolfe

2 August 1930

have spent twenty consecutive hours with your fifst book am enormously moved and grateful scott fitzgerald

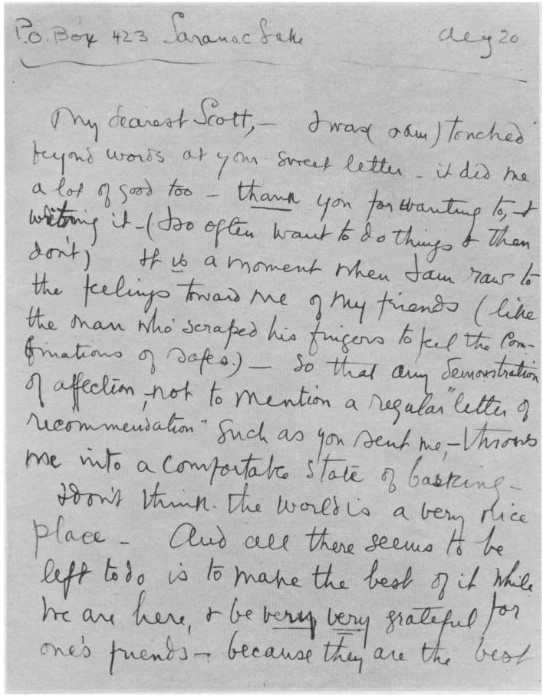

xxx. From Thomas Wolfe To A. S. Frere-Reeves

Hotel Lorius Montreux

Aug. 2, 1930

Dear Frere:

<…>

The weather is hot but very fine here, and my pastime is to eat that good lake fish you like so well. Scott Fitzgerald telegraphed me from Paris this morning that he had just finished my first book after twenty consecutive hours, and that he was “enormously moved and grateful.” I hope he repents and leads a better life hereafter. I am working on my new book every day.

P.S. And please send the author a copy of that English first edition before it becomes so damned valuable he can’t afford to buy it!

xxx. From Thomas Wolfe To John Hall Wheelock

Grand Hotel Bellevue Geneva

August 18, 1930

Dear Jack:

Thanks very much for your good letter. There is very little that I can say to you now except that (1) I have stopped writing and do not want ever to write again.

The place that I had found to stay—Montreux—did not remain private very long: (2) Fitzgerald told a woman in Paris where I was, and she cabled the news to America—I have had all kinds of letters and cables speaking of death and agony, from people who are perfectly well, and leading a comfortable and luxurious life among their friends at home. In addition, one of Mrs. Boyd’s “young men" descended upon me, or upon Montreux, and began to pry around. This, of course, may be an accident, but too many accidents of this sort have happened.

<…>

xxx. From Thomas Wolfe To Henry T. Volkening

Hotel Freiburger Hof

Freiburg, Germany

[September, 1930; the letter was never sent but was found among Wolfe’s papers.]

Dear Henry:

Please forgive me for having made you such a poor return for your fine letters. I haven’t been too busy to write ... I have two very long unfinished letters to you stuffed in among my junk: the reason I didn’t send them was that I couldn’t finish them—they would have each been ten million words long, and then I should not have been able to tell you about it ... The only way I’ll ever be able to tell you about these last four months, Henry, is to talk to (not with) you, and I long to do this, although I do not know how long it will be before I have that happiness. You must prepare yourself for the ordeal in whatever far off future: clasp a bottle of your bootlegger’s finest brew in your right hand and endure until the tidal wave shall have spent its force.

I am at length in the Black Forest. I arrived here a few days ago by a kind of intuition—the inside of me was like a Black Forest and I think the name kept having its unconscious effect on me. It is a very beautiful place —a landscape of rich, dark melancholy, a place with a Gothic soul, and I am glad that I have come here. These people, with all that is bestial, savage, supernatural, and also all that is rich, profound, kindly and simple, move me more deeply than I can tell you. France at the present time has completely ceased to give me anything. That is no doubt my fault, but their books, their art, their cities, their people, their conversation—nothing but their food at the present time means anything to me. The Americans in Paris would probably sneer at this—I mean these Americans who know all about it and are perfectly sure what French literature and French civilization stand for, although they read no French books, speak little of the language, and are never alone with French people.

I cannot tell you much at present about these last four months: I will tell you that I have had some of the worst moments of my life during them, and also some of the best. All told, it has been a pretty hard time, but I am going to be all right now. I don't know if you have ever stayed by yourself for so long a time (few people have and I do not recommend it) but if you are at all a thoughtful person, you arc bound to come out of it with some of your basic ore—you’ll sweat it out of your brain and heart and spirit. The thing I have done is one of the crudest forms of surgery in the world, but I knew that for me it was right. I can give you some idea of the way I have cut myself off from people I knew when I tell you that only once in the past six weeks have I seen anyone I knew—that was Mr. F. Scott Fitzgerald, the master of the human heart, and I came upon him unavoidably in Geneva a week or two ago.

I can tell you briefly what my movements have been: I went to Paris from New York and, outside of a short trip to Rouen and a few places near Paris, I stayed there for almost two months. I think this was the worst time of all: I was in a kind of stupor and unfit to see anyone, but I ran into people I knew from time to time and went to dinner or the theatre with them. My publisher came over from England and was very kind—he is a very fine fellow—he took me out and I met some of the celebrities—Mr. Michael Arlen and some of the Left Bank People. This lasted little over a day: I was no good with people and I did not go back to see them. I began to work out of desperation in that noisy, sultry, uncomfortable city of Paris and I got a good deal done. Finally I got out of it and went to Switzerland. I found a very quiet, comfortable hotel in Montreux; I had a good room with a balcony over-looking the lake; and in the weeks that followed I got a great deal accomplished.

I knew no one here at all—the place was filled with itinerant English and American spinsters buying postcards of the Lake of Geneva—but one night I ran into the aforesaid Mr. Fitzgerald, your old time college pal and fellow-Princetonian 1. I had written Mr. F. a note in Paris, because Perkins is very fond of him and told me for all his faults he’s a fine fellow, and Mr. F. had had me to his sumptuous apartment near the Bois for lunch and three or four gallons of wine, cognac, whiskey, etc. I finally departed from his company at ten that night in the Ritz Bar where he was entirely surrounded by Princeton boys, all nineteen years old, all drunk, and all half-raw. He was carrying on a spirited conversation with them about why Joe Zinzendorff did not get taken into the Triple-Cazzaza Club: I heard one of the lads say “Joe’s a good boy, Scotty, but you know he’s a fellow that ain’t got much background.”—I thought it was time for Wolfe to depart, and I did.

I had not seen Mr. F. since that evening until I ran into him at the Casino at Montreux. That was the beginning of the end of my stay at that beautiful spot. I must explain to you that Mr. F. had discovered the day I saw him in Paris that I knew a very notorious young lady, now resident in Paris getting her second divorce, and by her first marriage connected with one of those famous American families who cheated drunken Indians out of their furs seventy years ago, and are thus at the top of the established aristocracy now. Mr. F. immediately broke out in a sweat on finding I knew the lady and damned near broke his neck getting around there: he insisted that I come (“Every writer,” this great philosopher said, “is a social climber.”) and when I told him very positively I would not go to see the lady, this poet of the passions at once began to see all the elements of a romance—the cruel and dissolute society beauty playing with the tortured heart of the sensitive young writer, etc.: he eagerly demanded my reasons for staying away. I told him the lady had cabled to America for my address, had written me a half dozen notes and sent her servants to my hotel when I first came to Paris, and that, having been told of her kind heart, I gratefully accepted her hospitality and went to her apartment for lunch, returned once or twice, and found that I was being paraded before a crowd of worthless people, palmed off as someone who was madly in love with her, and exhibited with a young French soda jerker with greased hair who was on her payroll, and who, she boasted to me, slept with her every night. (“I like his bod-dy,” she hoarsely whispered, “I must have some bod-dy whose bod-dy I like to sleep with,” etc.)

The end finally came when she began to call me at my hotel in the morning, saying she had had four pipes of opium the night before and was “all shot to pieces,” and what in God’s name would she do: she had not seen Raymond or Roland or Louis or whatever his name was for four hours; he had disappeared; she was sure something had happened to him; that I must do something at once; that I was such a comfort she was coming to the hotel at once; I must hold her hand, etc. It was too much. I didn’t care whether Louis had been absent three or thirty hours, or whether she had smoked four or forty pipes, since nothing ever happens to these people anyhow—they make a show of recklessness but they take excellent care they don't get hurt in the end—and for a man trying very hard to save his own life, I did not think it wise to try to live for these other people and let them feed upon me.

So I told Mr. F., the great analyst of the soul, to tell the woman nothing about me, to give no information at all about me or what I was doing, or where I was. I told him this in Paris, I told him again in Switzerland, and on both occasions the man got to her as fast as he could. That ended Montreux for me. She immediately sent all the information back to America—and the heart-rending letters, cables, etc., with threats of coming to find me, going mad, dying, etc. began to come directly to my hotel. I wanted to batter the walls down. The hotel people, who had been very kind to me, charged me three francs extra because I had brought a bottle of wine from outside into the hotel. (They have a right in Switzerland to do this), but I took my rage out on them, told them I was leaving next day, went on a spree, broke windows, plumbing fixtures, etc. in the town, and came back to the hotel at 2 A.M., pounded on the door of the director and on the doors of two English spinsters, rushed howling with laughter up and down the halls, cursing and singing—and in short, had to leave.

I went to Geneva where I stayed a week or so. Meanwhile my book came out in England. I wrote beforehand and asked the publisher not to send reviews because I was working on the new one and did not want to be bothered: he wrote back a very jubilant letter and said the book was a big success and said “Read these reviews—you have nothing to be afraid of.” I read them; they were very fine; I got in a state of great excitement. He sent me great batches of reviews then—most of them very good ones, some bad. I foolishly read them and got in a very excited condition about a book I should have left behind me months ago. On top of this, and the cables and letters from New York, I got in Geneva two very bad reviews —cruel, unfair, bitterly personal. I was fed up with everything: I wrote Perkins a brief note telling him good-bye, please send my money, I would never write again, etc; I wrote the English publisher another; I cut off all mail by telegraph to Paris; I packed up, rushed to the aviation field and took the first airplane, which happened to be going to Lyons...

It was a grand trip, lasted three weeks, and did me an infinite amount of good. All the time I scrawled, wrote, scribbled. I have written a great deal—my book is one immense long book made up of four average-sized ones, each complete in itself, but each part of the whole. I stayed in Geneva one day and of course Mr. F. was on the job, although he had been at Vevey and then at Caux. His wife, he says, has been very near madness in a sanatorium at Geneva, but is now getting better. (It turned out that she was a good half hour by fast train from Geneva.) When I told him I was leaving Geneva and coming to the Black Forest, he immediately decided to return to Caux. I was with him the night before I left Geneva; he got very drunk and bitter; he wanted me to go and stay with his friends Dorothy Parker and some people named Murphy 2 in Switzerland nearby. When I made no answer to this invitation, he was quite annoyed; said that I got away from people because I was afraid of them, etc. (which is quite true, and which I think, in view of my experiences with Mr. F. et al, shows damned good sense. I wonder how long Mr. F. would last by himself, with no more Ritz Bar, no more Princeton boys, no more Mr. F.). At any rate, I came to Basel, and F. rode part way with me on his way back to Caux.

A final word about him: I am sorry I ever met him; he has caused me trouble and cost me time; but he has good stuff in him yet. His conduct to me was mixed with malice and generosity; he read my book and was very fine about it: then his bitterness began to qualify him: he is sterile and impotent and alcoholic now, and unable to finish his book, and I think he wanted to injure my own work. This is base, but the man has been up against it: he really loves his wife and I suppose helped get her into this terrible fix. I hold nothing against him now—of course he can't hurt me in the end—but I trusted him and I think he played a shabby trick by telling tales on me.

At any rate, I got over my dumps very quickly, sweated it out in Provence, and here I am, trying to finish up one section of the book before I leave here. I may go to England where Reeves, my publisher, assures me I can be quiet and work in peace: I like him immensely and there are also two or three other people there I can talk to. I have never been so full of writing in my life—if I can do the thing I want to, I believe it will be good.

I found a great batch of letters and telegrams when I got back from exile. Reeves was very upset by my letter and was wiring everywhere. He sent me a very wonderful letter: he said the book had had a magnificent reception and not to be a damned fool about a few reviews. And Perkins wrote me two wonderful letters—he is a grand man, and I believe in him with all my heart. All the others at Scribners have written me, and I am ashamed of my foolish letters and resolved not to let them down.

I know it’s going to he all right now. I believe I’m out of the woods at last. Nobody is going to die on account of me; nobody is going to suffer any more than I have suffered: the force of these dire threats gets a little weaker after a while, and I know now, no matter what anyone may ever say. that in one situation I have acted fairly and kept my head up. I am a little bitter at rich people at present: I am a little hitter at people who live in comfort and luxury, surrounded by friends and amusement, and yet are not willing to give an even chance to a young man living alone in a foreign country and trying to get work done. I did all that was asked of me; I came away here when I did not want to come; I have fought it out alone; and now I am done with it. I do not think it will be possible for me to live in New York for a year or two, and when I come back I may go elsewhere to live. As for the incredible passion that possessed me when I was twenty-five years old and that brought me to madness and, I think, almost to destruction—that is over: that fire can never be kindled again.

[the letter breaks off here]

Notes:

1 Volkening went to Princeton six years after Fitzgerald and did not know him, but says that Wolfe always persisted in lumping them together as Princeton men.

2 Mr. and Mrs. Gerald Murphy of New York.

xxx. TO: H. L. and Sara Mencken

ALS, 1 p. Enoch Pratt Library

c/o Guaranty Trust

4 Place de la Concorde Paris, France

Dear Menk and Sarah:

Excuse these belated congratulations,1 which is simply due to illness. Zelda and I were delighted to know you were being married + devoured every clipping sent from home. Please be happy

Ever your Friend Scott (and Zelda) Fitzgerald

Oct 18th, 1930

Notes:

1 Mencken had married Sara Haardt, who grew up in Montgomery with Zelda Fitzgerald.

xxx. TO: Judge and Mrs. A. D. Sayre

CC, 3 pp. (fragment)

Princeton University

Paris, the 1st December 1930.

My dear Judge Sayre and Mrs. Sayre,

Herewith a summary of the current situation shortly after I wrote you: at length I became dissatisfied with the progress of the treatment—not from any actual reason but from a sort of American hunch that something could be done, and maybe wasn’t being done to expedite the cure.

The situation was briefly that Zelda was acting badly and had to be transferred again to the house at Praugras reserved for people under restraint—the form in her case being that if she could go to Geneva alone she would “see people that would get her out of her difficulties.”

When Forel told me this I was terribly perturbed and had the wires humming to see where we stood. I wrote Gros who is the head of the American hospital in Paris and the dean of American medecine here. Through the agency of friends I got opinions from medical specialists of all sorts and the sum and substance of the matter was as follows:

1°—That Forel’s clinique is as I thought the best in Europe, his father having had an extraordinary reputation as a pioneer in the field of psychiatry, and the son being universally regarded as a man of intelligence and character.

2°—That the final rescourse in such cases are two men of Zurich—Dr. Jung and Dr. Blenler, the first dealing primarily with neurosis and the second with psychosis, which is to say, that one is a psychoanalist and the other a specialist in insanity, with no essential difference in their approach.

With this data in hand and after careful consideration I approached Dr. Forel on the grounds, that I was not satisfied with Zelda’s progress and that I had always at the back of my mind the idea of taking her home, and asked for a consultation. I think he had guessed at my anxiety and he greeted the suggestion with a certain relief and thereupon suggested the same two men I had already decided to call in—so that it made a complete unit. I mean to say there was nothing left undone to prove that I was dealing with final authorities.

After much, much talk I decided on Blenler rather than Jung—this was important because these consultations cost about five hundred dollars and one can’t be complicated by questions of medical etiquette. He came down a fortnight ago, spent the afternoon with Zelda and then the evening with Forel and me. Here is the total result.

1°—He agreed absolutely in principle with the current treatment.

2°—He recognized the case (in complete agreement with Forel) as a case of what is known as skideophranie, a sort of borderline insanity, that takes the form of double personality. It presented to him no feature that was unfamiliar and no characteristic that puzzled him.

3°—He said in answer to my questions that over a field of many thousands of such cases three out of four were discharged, perhaps one of those three to resume perfect functioning in the world, and the other two to be delicate and slightly eccentric through life—and the fourth case to go right down hill into total insanity.

4°—He said it would take a whole year before the case could be judged as to its direction in this regard but he gave me hope.

5°—He discussed at length the possibility of an eventual discovery of a brain tumor for the moment unlikely and the question of any glandular change being responsible. Also the state of American medical thought on such matters. (Forel incidently was at the Congress of Psychiatrists at Johns Hopkins last spring). But he insisted on seeing the case as a case and to my questioning answered that he did not know and no one knew what were the causes and what was the cure. The principles that he believes in from his experience are those that he and the older Forel, the father, (and followed by Myers of John Hopkins) evolved are rest and “re-education,” which seems to me a vague phrase when applied to a mind as highly organized as Zelda’s. I mean to say that it is somewhat difficult to teach a person who is capable now of understanding the Einstein theory of space, that 2 and 2 actually make four. But he was hardboiled, regarded Zelda as an invalid person and that was the burden of his remarks in this direction.

6°—The question of going home. He said it wasn’t even a question. That even with a day and night nurse and the best suite on the Bremen, I would be taking a chance not justified by the situation,—that a crisis, a strain at this moment might make the difference between recovery and insanity, and this question I put to him in various forms i.e. the “man to man” way and “if it were your own wife”—and he firmly and resolutely said “NO”—not for the moment. “I realize all the possible benefits but no, not for the moment.”

7°—He changed in certain details her regime. In particular he felt that Forel was perhaps pushing her too much in contact with the world, expediting a little her connection with me and Scotty, her shopping expeditions to Geneva, her going to the opera and the theatre, her seeing the other people in the sanitarium (which is somewhat like a hotel).

8°—He not only confirmed my faith in Forel but I think confirmed Forel’s own faith in himself on this matter. I mean an affair of this kind needs to be dealt with every subtle element of character. Humpty Dumpty fell off a wall and we are hoping that all the king’s horses will be able to put the delicate eggshell together.

9°—This is of minor importance and I put it in only because I know you despise certain weaknesses in my character and I do not want during this tragedy that fact to blur or confuse your belief in me as a man of integrity. Without any leading questions and somewhat to my embarrassment Blenler said “This is something that began about five years ago. Let us hope it is only a process of re-adjustment. Stop blaming yourself. You might have retarded it but you couldn’t have prevented it.

My plans are as follows. I’m staying here on Lake Geneva indefinately because even if I can only see Zelda once a fortnight, I think the fact of my being near is important to her. Scotty I see once a month for four or five days,—it’s all unsatisfactory but she is a real person with a life of her own which for the moment consists of leading a school of twenty two French children which is a problem she set herself and was not arbitarily

Notes:

Dr. Paul Eugen Bleuler.

Dr. Adolf Meyer, psychiatrist at the Phipps Clinic of Johns Hopkins Hospital, who later treated Zelda Fitzgerald.

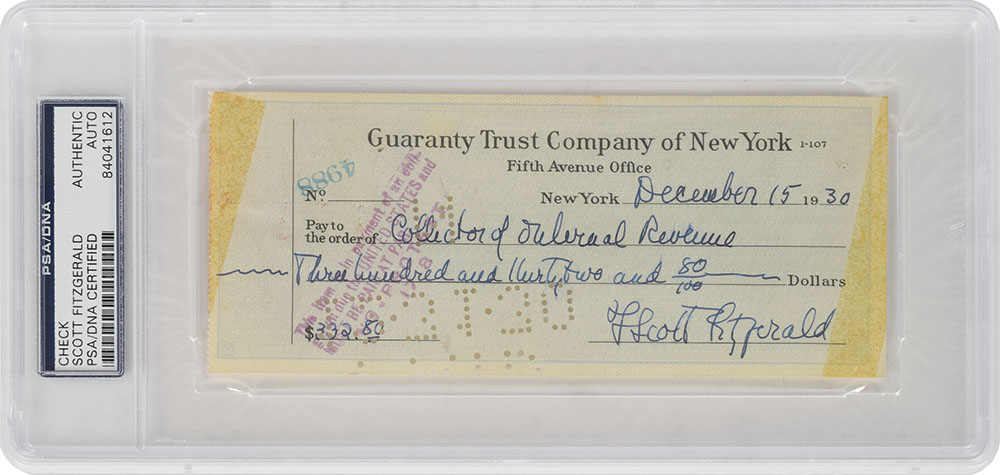

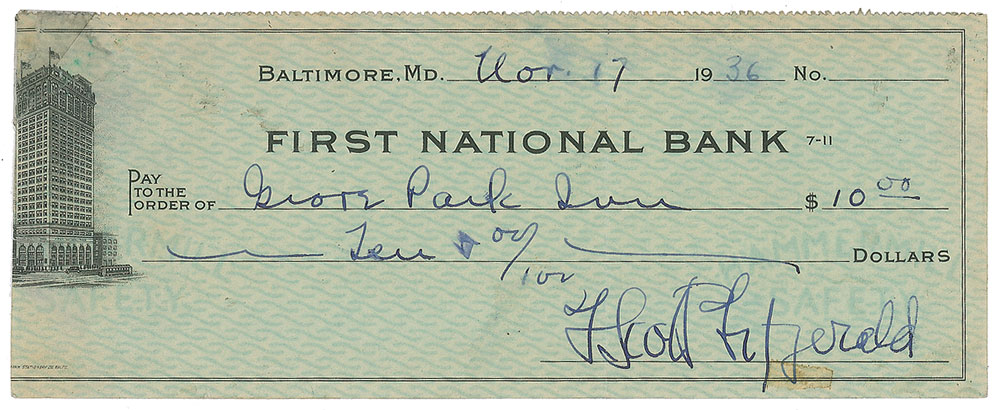

xxx. Bank Check

15 December, 1930.

Guaranty Trust Company of New York check, size 6.5 x 2.75, filled out and signed by F. Scott Fitzgerald, payable to Collector of Internal Revenue for $332.80

Notes:

Taxes.

1931

xxx. TO: Dr. Oscar Forel

CC, 7 pp. Princeton University

Paris

29th January, 1931.

Dear Dr. Forel,

After this afternoon I am all the more interested in my own theory.

I hope you will be patient about this letter. A first year medical student could phrase it better than I, who am not sure what a nerve or a gland looks like. But despite my terminological ignorance I think you’ll see I’m really not just guessing.

I am assuming with you and with Dr. Bleuler that the homosexuality is merely a symbol—something she invented to fill her slowly developing schizophenie. Now let me plot the course of her illness according to my current idea.

Youth & early womanhood Age 15–25

She has a nervous habit of biting to the bleeding point the inside of her mouth. With all her talents she is without ambition. She has been brought up in a climate not unlike the French Riviera but even there she is considered a lazy girl. A lovely but faulty complexion with blemishes accentuated by her picking at them.

Age 26–28

First appearance of definitely irrational acts (burning her old clothes in bath-tub in February 1927, age 26 years, 7 months). At this time she began to go into deep long silences and husband felt he has lost her confidence. Began dancing at age 27 and had two severe attacks of facial eczema cured by electric ray treatment. A feeling that she wasn’t well provoked tests for metabolism. Results normal.

Age 28–29 1/2

First mention of homosexual fears August 1928. This coincides with complete and never entirely renewed break of confidence with husband. From this time on work is intensive every day with extraordinary sweating, so much so that in the summers of ’28 and ’29 I have seen literal wet pools on the floor when watching her lessons.

April 29th, 1930

Collapse—and quick physical recovery. After two weeks’ rest at Malmaison she seemed better than she does now.

April–June

A confused period about which my own judgment is not reliable. Then comes

June–July

Hysteria, madness with moments of brilliance (her short stories etc.) Schizophrania well divided so that her Doctor finds her charming at one moment and yet is forced to confine her to the Eglantine the next. The good effect of this last measure. This period culminates with the visit of her daughter. Two very stirring experiences which have a marked effect on accentuating her best side—until—

August

Finding her to be ripe the doctor intensifies the process of reeducation, aiming at, for one thing, reconciliation with the husband. Things apparently progress. She writes nice and pleasant letters. She has good will again and hope and your interest in her case and hope for her is at its strongest. Suddenly as things reach a point where the meeting with husband and the resumption of serious life is a week off, when she has reached the point when the doctor has been able to try, though unsuccessfully, psycho-analysis she breaks out with virulent eczema. In this eczema she becomes necessarily more the invalid, the weakling, more self-indulgent. Her will power decreases. When the postponed meeting with the husband occurs she

September

brings to it only enough balance in favor of normality to last an hour and a renewed attack of eczema succeeds it.

Now I want to interrupt the sequence here to insert my idea. The original nervous biting, followed by the need to sweat might indicate some lack of normal elimination of poison. This uneliminated poison attacks the nerves.

When I used to drink hard for several days arid then stopped I had a tendency toward mild eczema—of elimination of toxins through the skin. (Isn’t there an especially intimate connection between the skin and the nerves, so that they share together the distinction of being the things we know least about?) Suppose the skin by sweating eliminated as much as possible of this poison, the nerves took on the excess—then the breakdown came, and due to the exhaustion of the sweat glands the nerves had to take it all, but at the price of a gradual change in their structure as a unit.

Now (I know you’re regarding this as the wildest mysticism but please read on)—now just as the mind of the confirmed alcoholic accepts a certain poisoned condition of the nerves as the one to which he is the most at home and in which, therefore, he is the most comfortable, Mrs. F. encourages her nervous system to absorb the continually distilled poison. Then the exterior world, represented by your personal influence, by the shock of Eglantine, by the sight of her daughter causes an effort of the will toward reality, she is able to force this poison out of the nerve cells and the process of elimination is taken over again by her skin.

In brief my idea is this. That the eczema is not relative but is the clue to the whole business. I believe that the eczema is a definite concurrent product of every struggle back toward the normal, just as an alcoholic has to struggle back through a period of depression.

October

To resume the calendar for a moment:

She is obviously making an effort. But at the same time comes the infatuation for the red-haired girl. At first I thought that caused the third attack of eczema but now I don’t. Isn’t it possible that it was her resistance, her initial shame at the infatuation and the consequent struggle that brought on the third eczema? This is supported by the fact that the infatuation continued after the eczema had gone. The eczema may have proceeded from the struggle toward reality rather than from the excitation itself.

The whole system is trying to live in equilibrium. When her will dominates her she doesn’t find it. I can’t help clinging to the idea that some essential physical thing like salt or iron or semen or some unguessed at holy water is either missing or is present in too great quantity. But to continue

November

Physical health fine but more in the hallucination. Growing vagueness and almost complete lack of effort. No eczema—but no effort. Her second infatuation does not cause eczema and neither does the

December

First visit of child. Because she behaves badly at my behest she makes an effort to think before the second visit and there is immediate eczema.

One more note and then I’ll draw my conclusions.

When she was discharged as cured from Malmaison she had facial eczema which we attributed to drugs. But it did not appear at Valmont or in early days at Prangins in spite of drugs at Valmont and disintoxication at Prangins for she was sunk safely in her insane self on both occasions.

My conclusions.

(a) The nature of any such poison would, of course, be too subtle for us. I believe she needs

(1) Naturally all you include under the term reeducation.

(b) Renewal of full physical relations with husband, a thing to be enormously aided by an actual timing of the visits to the periods just before and just after menstruation, and avoiding visits in the middle of such times or in the exact centre of the interval.

(c) To disintoxicate artificially in exact accord with the intensity of the reeducation. I can not believe that with her bad eyes that give her headaches and her many highly developed artistic appreciations, that embroidery, carpentry or book-binding are, in her case, any substitute for real sweating. She has a desire to sweat—for many summers she cooked all the pigments out of her skin tanning herself. I know this is difficult now but couldn’t she take intensive tennis lessons in the spring or couldn’t we think of something? Golf perhaps?

(d) Failing this I believe artificial eliminations should be absolutely concurrent with every effort at mental cure. I believe that constipation or delayed menstruations or lack of real exercise at such a time should be foreseen and forestalled as, in my opinion, eczema will always be the result.

I suppose the only new thing in all this is that I connect the eczema with one only sort of agitation the good sort and not with all agitation. Will you write me whether you agree at all while this is still fresh in your mind. I left my American addresses at the desk. Is her physical health good in general? Have her eyes been examined—she complains that her lorgnettes no longer work. The doctoress told me she had no warm underwear and I recommended some very light angora wool and silk stuff but Telda wouldn’t listen to me.

She was enormously moved by my father’s death or by my grief at it and literally clung to me for an hour. Then she went into the other personality and was awful to me at lunch. After lunch she returned to the affectionate tender mood, utterly normal, so that with pressure I could have manoeuvred her into intercourse but the eczema was almost visibly increasing so I left early. Toward the very end she was back in the schizophrania.

I was encouraged by our talk to-day. I am having this typed and translated and sent you from Paris. I shall be back in three or four weeks. Would you kindly cable me five or six words at about the middle of every week to the address LITOBER NEW YORK (my name not required).

Always gratefully yours,

Notes:

House at Prangins clinic for the most severely disturbed patients.

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

29 January-6 February 1931

Hamburg-Amerika Line letterhead

Bremen Feb 3d 1881

Madame—I hope to God you got some kind of sleep. No human being could possibly have all the stuff that I think you have, but you could divide that by two and still have enough left over to make a whole row of mixed debutantes and Tiller girls2 or what have you.

This letter is a sort of tender homage or would you like that big lilac tree in front of the dining room or a cargo mast (the latter covered with the facial hair of any man on board including the captain)?

Your Chattel Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

2 Troupes of dancers for musical comedies.

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

29 January-6 February 1931

Somewhat later

ALS, 3 pp. Princeton University

Hamburg-Amerika Line letterhead

Canal Boat “Staten Island” “Spend-a-dollar day” 1901

Pearl of the Adriatic: Another note because I am in terror you will wake up with an open trunk in front of you + confuse it with the trunk you last saw early this [ ] morning tottering, I might say weaving from your palatial suite—what I mean is I am sober, de-alcoholized, de-nicotinized de-onionized and I still adore you. Jay Obrien himself could say no more.

Is every member of you entourage so inflamed with jealousy at my wakefulness that it will be difficult to see you?—Douglass Fairbanksova Dostoieffski for example? I arrived on the last day but we parvenus have to be pushing or My God the rush of modern life would just—just well, devour us—that doesn't sound right, but whatever the rush of modern life does.

Be generous; don't be a lower bert' but an upper 'bert—even forgive that. I miss you. Will you meet me in the boiler room just inside the first canary cage at 12:15? I miss you. If you have breath in your body answer this.

Jay (Doctor of Medicine)

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

29 January-6 February 1931

Hamburg-Amerika Line letterhead

Even Later

Graf Zeppelin Stowaways Quarters

Are you just going to sleep and sleep? And sleep and sleep? Havn't you any feeling of public responsibility. Havn't you any invitations to fine country houses. Mrs. Jay Obrien would blush for you. I woke up thinking of you—I have tried to get my mind a decent break by feeding books to it but you are too much alive to let them have any reality.

Wake up. The sun is shining, the clocks are ticking, the nose is running. Life is tearing along, and you an old sleepy-head.

Dudley Field Malone Bishop of Bordeaux

I enclose my photograph

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 3 pp. Princeton University

29 January-6 February 1931

Hamburg-Amerika Line letterhead

The “Alps,” 6th Ave at 58th Near Nightfall

I put in a new razor blade for you + the texture of my skin is like duveteen or Gloria Morgan “Pond's Extract” Vanderbilt—it would not shame the greatest fairy that ever knitted a boudoir cap—and still no word. Are you recieving? Do you ever recieve? Did you ever think who killed Rothstien + Dorothy King?1 I did. After the fourth note + no answer I said if they like sleeping I'll help go on with it. Thats my story and no transfer conniesseur from Brooklyn can shake it. What if your father is President? What if Scott Fitzgerald did try to make you? Every girl's got to get off on her own initiative and any paddles broken or bloomers-ripped should be reported to Miss Rorer at the small cottage. Have I got to have the whole Hapag S.S. Line installed with room telephones to know you're still alive?

Fitzg—

Notes:

1 Gambler Arnold Rothstein and Dorothy King were victims of unsolved murders; Rothstein was the model for Wolfshiem in The Great Gatsby.

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 3 pp. Princeton University

New Yorker Hotel letterhead. New York City

feb 7th [1931]

So then you were gone + I couldn't whisper any more into the wooly top-knot of your hat. Everything was unreal again with all the women sitting naked on the tables + the men snarling among themselves + so I went behind my convenient bush—which is to say I got quite a lot drunk. I talked a lot to thisman thatman + that girl who was in ballet school with my wife but when I heard myself from the calm detached listening post that part of me was sitting in, telling her that she was mosh beautiful woom in a worl and asking Douglas fee had any ajections—I decided to get out which took twenty minutes of slow motion—I left the three of them in front of some cafe + came back to this lousy hotel with my briefcase in my arms, wondering about you + what you had gone home to + how long hours and days are.

So Mrs. Goldstien (Nee Mr. and Mrs Jay O'brien) so—there's some hours gone and to that extent you're nearer

Scott

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 3 pp. Princeton University

After 7 February 1931

Hotel Napoleon letterhead. Paris

Micky Mouse: This is Virginia with names like Manassas and Culpepper full of the Civil War + I've been thinking about my father again + it makes me sad like the past always does. So I'll think of you because that's happy, Dear Bert.

The management of Grand Hotel had two of their men scurrying about New York all afternoon trying to get seats for Charley + me. Finally they had to buy in two singles from different agencies + change around two parties to get a pair of seats together. Charley arrived at the theatre at eight o'clock, took his seat + went sound asleep for three hours. He remembers the curtain going up + a man coming on the stage but nothing after that except that at one point a woman asked him to take his head off her shoulder. I reached the theatre at the moment when the last curtain was going down and saw the knees + feet of what appeared to be a lot of bellboys. So no one can say that Scott Fitzgerald + Charles MacArthur havn't been to “Grand Hotel"—at least in spirit. I left him in a speakeasy with the indignant manager, Charley looking very wild + helpless as if a whole series of tournedos had xploded in his mouth

I sent the books to 50 Plaza St. If they havn't come please call Scribners retail dept. I'm particularly anxious for you to have them.

I miss you so Goddamn much

Scott

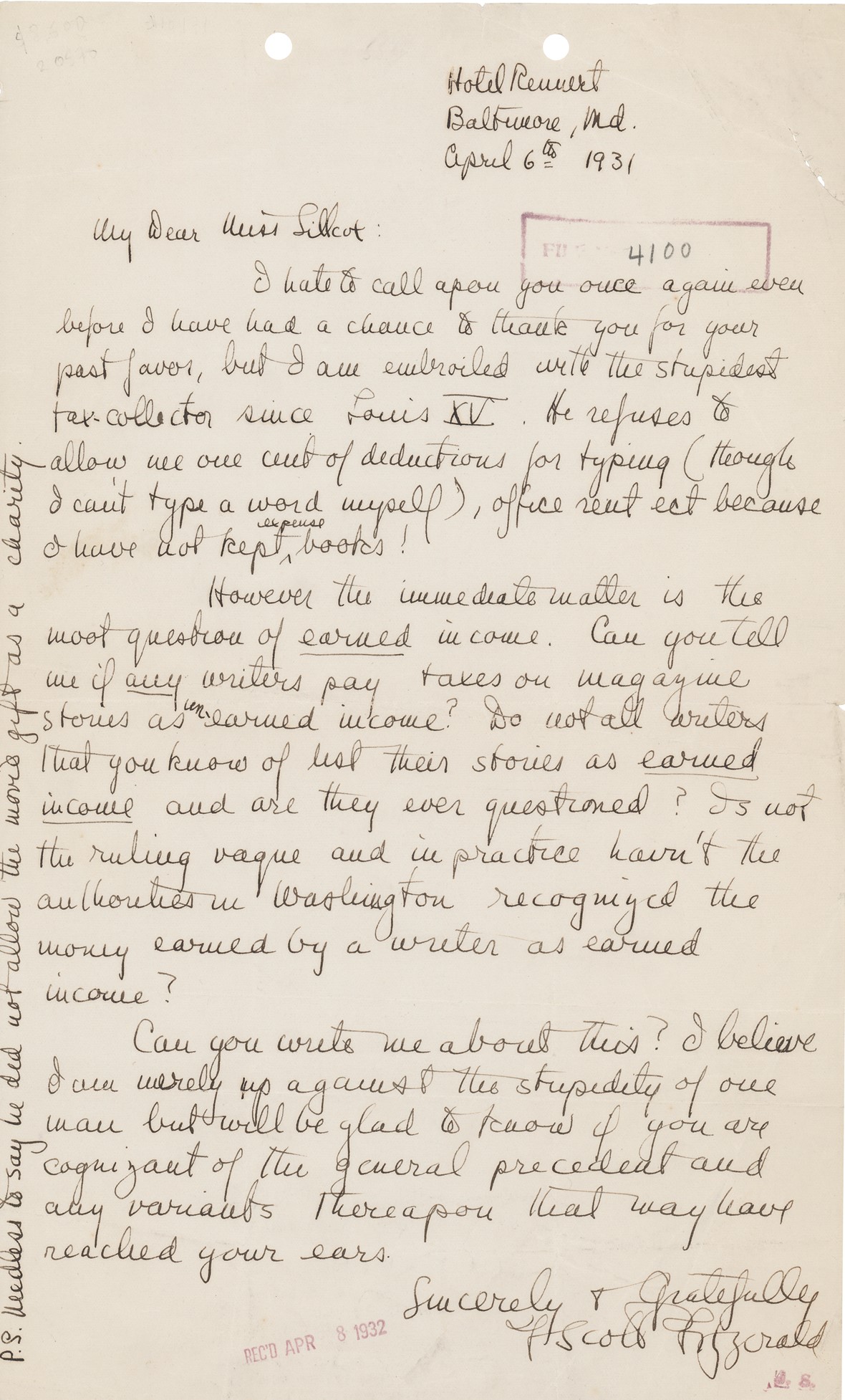

xxx. TO: H. L. Mencken

Wire. New York Public Library

1931 FEB 15 PM 6 35

MONTGOMERY ALA1

H L MENCKEN

WILL YOU KINDLY WIRE ME THE NAME OF THE BIGGEST PSYCHIATRIST AT JOHNS HOPKINS FOR NONORGANIC NERVOUS TROUBLES ADDRESS 2400 16TH ST WASHINGTON DC REGARDS

SCOTT FITZGERALD.

Notes:

1 After his father's funeral Fitzgerald went to Montgomery to report to the Sayres on Zelda's condition.

xxx. To Mrs. Richard Taylor (aka Cousin Ceci)

From Turnbull.

S.S. Olympic

February 23, 1931

My dearest Ceci:

I don't know what in hell I'd have done unless you had come up. The trip South was not so fortunate as it might have been, but it didn't blot out my sense of you and how much I have always loved you and depended on you. Thank you for your second note. I have always wanted, if anything happened to me while Zelda is still sick, to get you to take care of Scottie.

All those days in America 1 seem sort of blurred and dream-like now. Sometimes I think of Father, but only sentimentally; if I had been an only child I would have liked those lines I told you about of William McFee over his grave:—

“O staunch old heart that toiled so long for me: I waste my years sailing along the sea.”

Life got very crowded after I left you, and I am damned glad to be going back to Europe where I am away from most of the people I care about, and can think instead of feeling.

Gigi wrote me such a sweet letter, especially because it said that you liked me.

Dearest love to you.

Scott

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald had come back from Europe for his father's funeral.

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

March 1931

Grand H6tel de la Paix letterhead Lausanne, Switzerland

Darling Micky Mouse: Arrived here in bum condition + took to bed—immediately a pile of the most depressing American mail arrived so I got up + organized myself + my affairs + now things look brighter (by the way if you have any lingering jealously of that lady you'll be glad to know that I found a week-old note here saying she was leaving for America because of the serious illness of her ex-husband!)

It was too bad about us this time—we met like two crazyy people, both cross + worried + exhausted + as we're both somewhat spoiled we took to rows + solved nothing. It was rough too about the hotel—at the time I was angry at that woman but later the scene of her in the hall returns to me as something terribly sordid, a scene in a cheap boarding house, and both of us too dazed to face it + her properly.

It certainly indicates that we're not too good for each other at this precise moment—as you suggested we'd each better try to straighten out our affairs first, because we're so different that we have to have a certain patience toward each other + that's impossible in a condition of agitation. All of which doesn't mean that my tenderness toward you is diminished in the slightest but only that I want it to go on, + one more siege like those three days would finish us both + spoil everything for ever.

In any case I find I'm in debt again which means two weeks hard work and a life of complete ascetisism. As I told you the first two weeks in July belong to my family. Meanwhile if your own plans get clearer—and believe me dear child I appreceate what of a hell of a time you've had—the Guaranty Trust always reaches me quickest, because I may be here or in Nyon with my invalid.

I hope things are better + that you'll try to remember the best -|- not the worst of that bad time

Your Krazy Cat

xxx. TO: Alice Lee Myers

c. March 1931

ALS, 2 pp. Mrs. Richard Myers

Grand Hotel de la Paix letterhead Lausanne, Switzerland

Sweet Alice (Ben Bolt or no Ben Bolt):

What a hell of time all my friends have been having this year! Even the Bishops have twins. But when I think of poor Dick with part of his flesh cloven to another part I have the horrors thinking what it must feel like. But those things leave no mental scars. I had my nosebones sawed without anaesthetics at his age and it only taught that all misery is over eventually.

All right about Scotty if you'll trade Fanny for her. But tell Dick not to tell her she's pretty because she gets ugly for a week afterwards grimacing at herself in mirrors. You've been so damn nice to her and there's nobody I'd rather have her with than your children This must be an exception to the fact that children of friends invariably loathe each other. Scotty + the little Murphys begin to glare as soon as they're in a radius of a hundred yards from each other.

Christ knows about this summer. I'd certainly love to have Scotty visit you for a time—she'll be some, maybe a lot with her mother + I plan taking her for a months swimming. It's all vague.

I hope you have a great time in America. In spite of the heavy gloom of up-to-my-neck-in-crepe, I enjoyed the way people are getting down to work.

Zelda is much, much better. Only a few months from being well. I've skiied with her yesterday.

Much Much love from us both to all of you

Scott

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Guaranty Trust, Paris

March 1931

Darling Micky Mouse:

When are you coming over?—about when? approximately when? I know you buyers don't get here usually until about Aout while we contact men just go hither + thither at will—but I have mothers to take to Carlsbad, daughters to arrange vacations for, and I want to know when you're coming + how much of you I can see. Are you coming in Apr.;? May?; June? Your telegram made me think sooner. I'll meet you anywhere (like Mr. Cornell) and just so long as you go in for white evening purses I know it'll be worth my while.

Oh Bert! I remember:

“No jam tomorrow”—and

“I've got my gloves on” (preceded by a shriek of laughter) and

“I g't a paarler”, and

The exploding tournedos, and best of all

“Not one of the nicest episodes, the nicest episode.”

And I miss you so Goddamn much

So, as we agreed, let's not have such a long time interval between these Honalulu Beaches. Bert, dear.

Scott

xxx. TO: C. O. Kalman

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Grand Hotel de la Paix letterhead Lausanne, Switzerland

Guaranty Trust 4 Concorde

March 11th 1931

Dear Kaly:

I can't thank you enough for your kindness to mother. I love your “There is no charge for this as we are doing it every day.” Such a wonderful reason. I'm going to write Lorimer that I make no charge for my writing as I'm doing it every day. Can't you hear the barber's: “No, please sir—I won't take a penny—I'm doing it every day.” However there's probably some catch to it—you've found that cache of old prayer books I left in your mother's cellar or something like that + your conscience is troubling you. Far be it from me not to look for the motive behind—I suppose you think I'm going to write another story about you—well, I'm not—unless you get in some more interesting trouble.

I hear you're the only prominent Minnesotan that didn't get a Nobel Prize last year + that's why you're afraid to show your face in Europe.

Zelda is almost well—really well. I hope we'll be home in the fall. She's still in the clinique but I went ski-ing with her this afternoon.

All love, sacred + profane to Sandy + yourself

Scott F

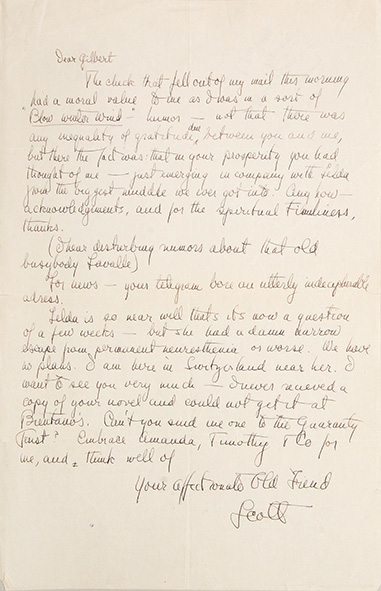

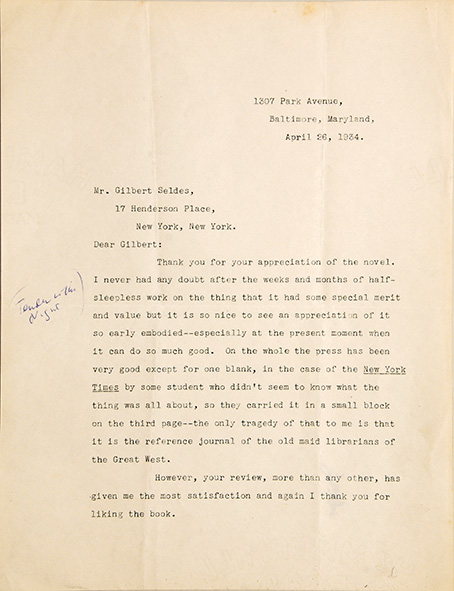

xxx. To Gilbert Seldes

One page ALS.

Undated, circa Spring 1931.

The check that fell out of my mail this morning… …just emerging in company with Zelda from the biggest muddle we ever got into… Zelda is so near well that its now a question of a few weeks – but she had a damn narrow escape from permanent neurasthenia or worse. We have no plans. I am here in Switzerland near her… Your Affectionate Old Friend, Scott.

Notes:

Fitzgerald writes to Gilbert Seldes from Switzerland, where Zelda was being treated at a clinic. Fitzgerald thanks him for a check.

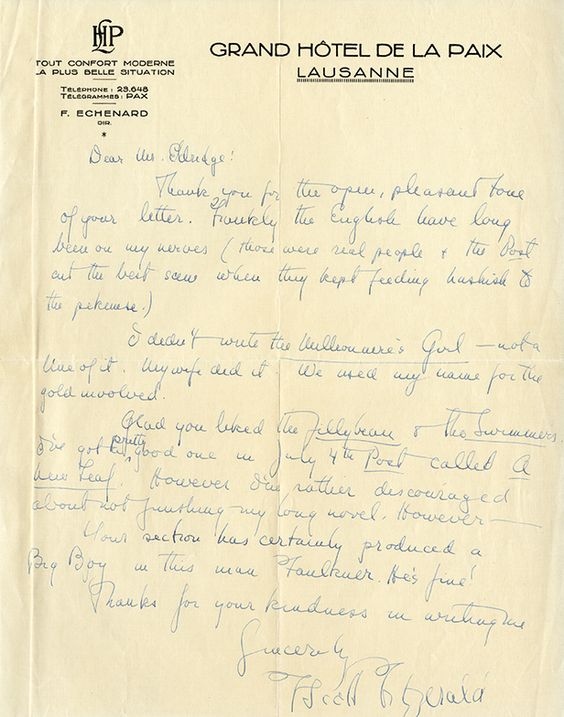

xxx. To Paul Eldridge

ALS, 1 page, Auction.

June 15, 1931.

Thank you for the open, pleasant tone of your letter Sincerely, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

xxx. TO: Alfred Dashiell

June 1931

ALS, 1 p. University of Virginia

Grand Hotel de la Paix letterhead Lausanne, Switzerland

Dear Mr. Dashiell:

As I wired—I'd like to do the article2 (It's already paid for!) It'll be ten days before I can send it, tho It'll reach you about early in July. Thanks for the idea

Yrs. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

2 “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” Scribner's Magazine (November 1931).

xxx. FROM: Gerald Murphy

TLS, 1 p. (with holograph postscripts). Princeton University

Summer 1931

Sunday.

Dear Scott:—

How great that everything seems to be going so well and that you can all really come here. We had begun to worry a little and expect an ugly letter from you. You've doubtless got my telegram saying that the fourth August will be fine. We return from Salzburg on the afternoon of the third after Patrick's next injection which takes place that morning. We stay at the Grand Hotel de l'Europe when there. It's not a bad idea that we see each other there that day, unless you're coming by another way (Zurich—Munich) to Bad Aussee.

Bring bathing suits.

The name of the property is RAMGUT, Bad Aussee, Steyrmark, Austria. Telephone number I. We are about 85 kilometres or two hours and one half easy going from Salzburg. I should suggest that you come by Zurich, Buchs, Innsbruck, Salzburg,—or if you want to go to Germany from the Swiss border and then South to Salzburg, go by Munich,—but by Innsbruck and the Austrian Tyrol is lovely.

Our schedule may be too tight a one to allow of our going to Vienna with you, as it will be just the moment that we are without a trained nurse for Patrick, the present one leaves August 3rd and Miss Stewart does not land until the 10th. But you and Zelda must go, Scottie can stay with us so easily until you come back to get her. It will give you and Zelda kind of a fling alone;—and we are on your way back.

The termination of your letter with it's patter of baby feet had what you would consider the desired effect upon Sara: sharp local pains followed by excessive retching.

Our love to you all. We are looking forward to seeing you,

Gerald.

[Across the top] Vienna is 5 hrs. (at most) due East of us by motor. We are on the direct road between Salzburg + Wien.

[Along left margin] Bring Express or A.B.A. checks for Austria + Germany,—otherwise it's difficult,—and if possible put USA somewhere on your car,—otherwise you're apt to be eaten for a Frog. With USA they strew roses.

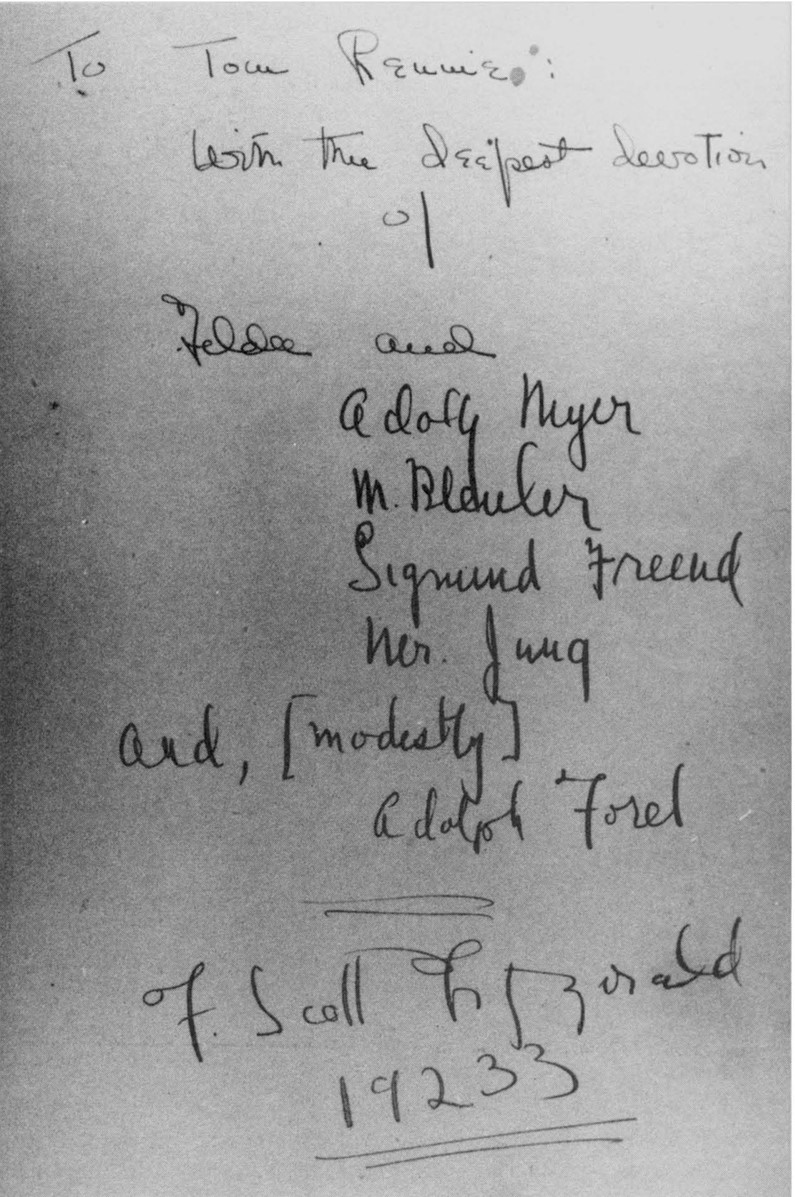

xxx. Inscription TO: Samuel Marx

Inscription in This Side Of Paradise, Auction

Hollywood

For Sam Marx who has just arranged my future for me—very different from the future of Amory Blaine,—from his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald Hollywood, 1931

xxx. FROM: Norma Shearer Thalberg

c. December 1931

Wire. Scrapbook. Princeton University

SCOTT FITZGERALD

CHRISTIE HOTEL HOLLYWOOD CALIF

I THOUGHT YOU WERE ONE OF THE MOST AGREEABLE PERSONS AT OUR TEA

NORMA THALBERG.

Notes:

While working in Hollywood on Red-Headed Woman, Fitzgerald got drunk at a party in the Thalbergs' home and performed for the guests. “Crazy Sunday” is based on this incident.

xxx. TO: Bert Barr

1931

Inscription in This Side of Paradise. Princeton University

Dear Bert:

This book is silly + dated now but it made me a name when I was very young. It was the first book about necking + the younger generation—way back before Flaming Youth or such things

Affectionately Yours F Scott Fitzgerald

xxx. FROM: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

16 December 1931

Official Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer document signed. Auction

This will confirm the agreement between us that the term of your employment under your contract of employment with us dated November 7, 1931, shall be deemed to have expired on December 15, 1931… it being expressly understood that we shall have and retain all rights of every kind granted to us under said contract.

[pencil annotation at the bottom] Mr. Thalberg signed original copy only. Mr. Mayer signed 2 copies. Copies signed by L. B. Mayer sent to Ober & Craig.

Notes:

In his second stint in Hollywood, Fitzgerald spent a four-week assignment working on the script for Red-Headed Woman, a screenplay to be adapted from Katharine Brush's novel of the same name. Thalberg found his script to be too serious, and turned it over to Anita Loos for a rewrite. Loos delivered a script with more playful banter, and the Jean Harlow vehicle—with Loos's solo screen credit—became a box office success. Dismayed by his failure, Fitzgerald returned east after MGM releases Fitzgerald from his contract.

1932

xxx. TO Dayton (?) Kohler

From Turnbull.

819 Felder Avenue Montgomery, Alabama

January 25, 1932

Dear Mr. Kohler:

The reason for my long delay in writing you is this—shortly after receiving your letter I left France for Switzerland in terrible confusion because of the sickness of my wife. My current correspondence was packed by mistake in a crate—which has only just been opened. I am terribly sorry.

I was delighted naturally with your article about me. You cover me with soothing oil and make me feel more important than I have for ages.

I am mid-channel now in a double-decker novel which I hope will justify some of the things that you say. Perhaps Swanson of College Humor or someone there might be interested—for the moment I am vieux jeu and completely forgotten by the whole new generation which has grown up since I published my last book in '26. So since there has been no published development since then, I think the article would be for the present hard to sell.

I am doubly grateful for your interest and again I apologize for my apparent discourtesy in not answering you before.

If you are ever in Montgomery, Alabama, I would love to see you. My address is 819 Felder Avenue.

Sincerely,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

xxx. TO: Dr. Mildred Squires

CC of retyped letter, 2 pp.

Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives,

Johns Hopkins Hospital

Montgomery, Alabama

Zelda Fitzgerald

#6408

3.14.32

Letter from husband.

Dear Dr. Squires:

Zelda’s novel, or rather her intention of publishing it without any discussion, has upset me considerably. First, because it is such a mixture of good and bad in its present form that it has no chance of artistic success, and, second, because of some of the material within the novel.

As you may know I have been working intermittently for four years on a novel which covers the life we led in Europe. Since the spring of 1930 I have been unable to proceed because of the necessity of keeping Zelda in sanitariums. However, about fifty thousand words exist and this Zelda has heard, and literally one whole section of her novel is an imitation of it, of its rythym, materials, even statements and speeches. Now you may say that the experience which two people have undergone is common is common property—one transmutes the same scene through different temperments and it “comes out different” As you will see from my letter to her there are only two episodes, both of which she has reduced to anecdotes but upon which whole sections of my book turn, that I have asked her to cut. Her own material—her youth, her love for Josaune, her dancing, her observation of Americans in Paris, the fine passages about the death of her father—my critisisms of that will be simply impersonal and professional. But do you realize that “Amory Blaine” was the name of the character in my first novel to which I attached my adventures and opinions, in effect my autobiography? Do you think that his turning up in a novel signed by my wife as a somewhat aenemic portrait painter with a few ideas lifted from Clive Bell, Leger, ect. could pass unnoticed? In short it puts me in an absurd and Zelda in a rediculous position. If she should choose to examine our life together from an inimacable attitude & print her conclusions I could do nothing but answer in kind or be silent, as I chose—but this mixture of fact and fiction is simply calculated to ruin us both, or what is left of us, and I can’t let it stand. Using the name of a character I invented to put intimate facts in the hands of the friends and enemies we have accumulated enroute—My God, my books made her a legend and her single intention in this somewhat thin portrait is to make me a non-entity. That’s why she sent the book directly to New York.

Of course were she not sick I would have to regard the matter as an act of disloyalty or else as something to turn over to a lawyer. Now I don’t know how to regard it. I know however that this is pretty near the end. Her mother thinks she is an abused angel incarcerated there by my bad judgement or ill intention. In the whole family there is just a bare competence save what I dredge up out of my talent and work to pay for such luxuries as insanity. But Scotty and I must live and it is getting more and more difficult in this atmosphere of suspicion to turn out the convinced and well-decorated sopiusous for which Mr. Lorimer pays me my bribe.

My suggestion is this—that you try to find why Zelda sent to the novel north without getting my advice, which, as I have given her her entire literary education, all her encouragement and all her opportunity, was the natural thing to do.

Secondly that you tell Mrs. Sayre that I am any kind of a villain you want, and that you have private information on the fact, but htat her daughter is sick, sick, sick, and that there is no possibility of being mistaken on that.

Third—keep the novel out of circulation until Zelda reads my detailed criticism & appeal to reason which will take two days more to prepare.

Meanwhile I will live here in a state of mild masturbation and a couple of whiskys to go to sleep on, until my lease expires April 15th when I will come north. I appreciate your letters and understand the difficulties of prognosis in this case. My sister-in-law will be north this week. She is a trivial, charming woman and we dislike each other deeply. Her observation or analysis of any given series of facts is open to the same skeptesism as that of any member of the Sayre family—they left the habit of thinking to the judge for so long that it practically has become a parlor game with them.

I enclose Zelda a check for fifty dollars.

Yours Sincerely & Gratefully

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

The original draft of Save Me the Waltz, written while Zelda Fitzgerald was in the Phipps Clinic, has not survived.

Bell was a British art critic; Fernand Leger was a French painter.

xxx. TO: Dr. Mildred Squires

CC of retyped letter, 1 p.

Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives,

Johns Hopkins Hospital

Montgomery, Alabama

Zelda Fitzgerald

#6408

no date (I think 3.20.32)

Letter from husband.

Dear Dr. Squires:

On the advice of a doctor here I sent Zelda a very much shortened version of the letter here inclosed which incorporate my ideas on the subject of her self expression. I am simply unable to depart from my professional attitude—if you think that in any way I have departed from it please tell me—but I think that what further speculation we indulge in are in the realms of the most highly experimental ethics. I feel helpless and alone in the face of the situation; nevertheless I feel myself a personality, and if the situation continues to shape itself as one in which only one of us two can survive, perhaps you would doing a kindness to us both by recommending a separation. My whole stomach hurts when I contemplate such an eventuality—it would be throwing her broken upon a world which she despises; I would be a ruined man for years—but, alternatively, I have reached the point of submersion if I must continue to rationalize the irrational, stand always between Zelda and the world and see her build this dubitable career of hers with morsels of living matter chipped out of my mind, my belly, my nervous system and my loins. Perhaps fifty percent of our friends and relatives would tell you in all honest conviction that my drinking drove Zelda insane—the other half would assure you that her insanity drove me to drink. Niether judgement would mean anything: The former class would be composed of those who had seen me unpleasantly drunk and the latter of those who had seen Zelda unpleasantly psychotic. These two classes would be equally unanimous in saying that each of us would be well rid of the other—in full face of the irony that we have never been so desperately in love with each other in our lives. Liquor on my mouth is sweet to her; I cherish her most extravagant hallucination.

So you see I beg you not to pass the buck to me. Please, when I come north, remember that I have exhausted my intelligence on the subject—I have become a patient in the face of it. Her affair with Edward Josaune in 1925 (and mine with Lois Moran in 1927, which was a sort of regenge) shook something out of us, but we can’t both go on paying and paying forever. And yet I feel that that’s the whole trouble back of all this.

I will see you Thursday or Friday—I wish you’d tell me then what I ought to do—I mean I wish that you and Doctor Myers would re-examine the affair,

Sincerely

F. Scott Fitzgerald

xxx. TO: Dr. Mildred Squires

Spring 1932

CC of retyped letter, 2 pp.

Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives,

Johns Hopkins Hospital

Baltimore, Maryland

FITZGERALD, Zelda

Letter from husband.

# 6408

Saturday Evening

Dear Dr. Squires:

The whole current lay-out is somewhat discouraging. I seem to be bringing nothing to its solution except money and good will—and Zelda brings nothing at all, except a power of arousing sumpathy. She has perhaps achieved something fairly good, at everybodys cost all around, including especially mine. She thinks she has done a munificent thing in changing the novel at all—she has become as hard and coldly egotistic as she was when she was in the ballet and I would no more think of living with her as she now than I would repeat those days. The one ray of hope is this—that once the novel is sent off (it has almost torn down all the relations patiently built up for a year) she must not write any more personal stuff while she is under treatment. What has happened is the worst possible thing that could have happened—it has put her through a detailed recapituation of all the worldly events that first led up to the trouble, embittering her in retrospect, and then been passed back through me, so that I’ve been in an intolerable position. Through no fault of yours her stay at the clinic has resolved itself into a very expensive chance to satisfy her desire for self-expression. We are farther apart than we have been since she first got sick two years ago and this time I have no sense of guilt what soever.

Now some particular points (alas, unrelated!)

First: In regard to our phone conversation. Our sexual relations have been good or less good from time to time but they have always been normal. She had her first orgasm about ten days after we were married, and from that time to this there haven’t been a dozen times in twelve years , when she hasn’t had an orgasm. And since the renewal of our relations last spring that accident has never occurred and our relations, in that regard up to the day she entered Johns Hopkins were more satisfactory than ever before (Also O. K. here in Bait, as explained)

The difficulty in 1928–1930 was tempermental—it led to long periods of complete lack of desire. During 1929 we were probably together only two dozen times and always it was purely physical, but in so far as the purely physical goes it was mutually satisfactory. I have had experience & read all available literature, including that book by the Dutchman I saw on your shelves and I know whereof I speak.

On the other hand I think it is unfortunate she has had no more children; also she’s probably a rather polygamus type; and possibly she has, when not herself, a touch of mental lesbianism. The first and third things I can’t do anything about—the second thing I simply I couldn’t stand for and stillfeel any nessessity to preserve the family.

Second She weighed 110 on a slot machine today, dressed, and told me she’d been losing weight. She eats, when she’s with me, two packs of mints, tho sugar has always caused her acne. I asked her if she’d like to go down the valley (Shenendoah) & spend a night next Saturday. Else, I said, I’d like to go to New York for a day or so, wanting a change. She had no interest in the valley trip, but asked why didn’t I go to New York? There is a vague form in her mind of “go on—do what you want—All I want is a chance to work.” The only essential that she leaves out is that I also want a chance to work, to cease this ceaseless hack work that her sickness compells me to. You will see that some blind unfairness in the novel. The girl’s love affair is an idyll—the man’s is sordid—the girl’s drinking is glossed over (when I think of the two dozen doctors called in to give her 1/5 grain of morphine or a raging morning!), while the man’s is accentuated. However there’s no use going over that again. It’s all been somewhat modified. The point is that there’s no working basis between us and less all the time—unless this novel finishes a phase in her life & it all grows dim with having been written. That’s the best hope at present. But she musn’t start another personal piece of work—she spoke today of a novel “on our personal quarrel & her insanity.” Should she begin such a work at present I would withdraw my backing from her immediately because the sands are running out again on my powers of indurance—I can’t pay for the smithy where she forges a weapon to bring down on mine and Scottys &, eventually, her own head, for all the pleasant exercise it may give her mental muscles.

Also she spoke of a play again. That would do no harm because its more cold & impersonal—it might overlay the memory of the novel & all that the novel evoked. Ironicly enough I gave her the plan for the novel, recommended autobiography ect, with no idea that this would happen.

Third I have vague ideas of (a) tennis lessons for her (I still think of the ski-ing & her nessessity of being superior at something.) (b) A few spring clothes—to encourage minor vanities in place of this repellant & devastating pride (c) trying her without nurses to see how she will do her stuff there. Or, for a week: Apparently without nurses.