“A Cheer For Princeton!”

The Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edmund Wilson, and John Peale Bishop

1. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

August 28, 1915

Dear Fitz: I wrote a whole first act, lyrics and all; some of it was exquisitely humorous and some of it was very weak.* I sent it to Lane and told him to forward it to you, when he had' finished with it, because I was too lazy to make another copy. He returned it to me with a long letter explaining that he liked it but that there were a number of important changes he wanted me to make. My impression was that he had failed to appreciate the exquisite humor of the exquisitely humorous parts but had fully appreciated the weakness of the weak parts. I received the package the night before I left for the West and didn't want to take it with me.

Lane wrote that he would send it to you, when he got it back the second time from me. I suppose the best thing I can do now is to write home for it to be sent now to you. I am sick of it myself. Perhaps you can infuse into it some of the fresh effervescence of youth for which you are so justly celebrated. The spontaneity of the libretto has suffered somewhat from the increasing bitterness and cynicism of my middle age.

Another thing, I thought until today that I was coming to St. Paul on my way East. Now I am almost sure it can't be done and so I shan't have an opportunity for talking it over personally with you until college opens. At any rate, I'll have the MS sent to you at once.

Yours etc. E.W.

Notes:

* “'The Evil Eye' … Edmund Wilson, Jr. wrote the book and Scott Fitzgerald wrote the lyrics … for the elaborately costumed annual performance of the Triangle Club … It was a howling success.”—Christian Gauss, “Edmund Wilson—the Campus and the Nassau 'Lit,'” in The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 1944.

2. [Fragment] from the diary of Edmund Wilson

taken from: Wilson, E. A Prelude, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: “Why, I can go up to New York on a terrible party and then come back and go into the church and pray—and mean every word of it, too!”

[Scott was then a practicing Catholic, and though I sometimes used to kid him about it—he was the first educated Catholic I had ever known—I now think it was perhaps unfortunate that he lost his faith as he did. In his college days, the older men who were most interested in him and whom he most respected were Father Fay and Shane Leslie. I suppose it was inevitable that in an all- Protestant college—I do not remember in my time any other Catholic students, though there may have been a few—a college which had for him, a Westerner, the prestige of an acme of Eastern smartness, he should have imitated his companions in not taking religion seriously. But this left him with nothing at all to sustain his moral standards or to steady him in self-discipline. His desire to be a great writer only intermittently spurred him to effort. He had put on record before his death that he wanted to be buried in the Catholic cemetery in Baltimore with the other members of his family, but this was denied him by the Church, to which, after breaking away from it, he had never made his resubmission.]

3. [Fragment] from the diary of Edmund Wilson

taken from: Wilson, E. A Prelude, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967.

<…>

The situation at Yale was quite different. You were first asked to join a fraternity, and you could live in a fraternity house—we were not allowed to live in the clubs till the days when we came back as alumni. The election to the senior societies took place at the end of the junior year at the solemn ceremony of “Tap Day,” when the class waited under a certain tree for the seniors to run out of the society buildings—w'indowless and forbidding stone tombs, illuminated only from the top—tap their men and say “Go to your room!” Mysterious rites followed, which the members were pledged not to reveal. Of these senior societies at Yale, Skull and Bones was by far the most important. It was supposed to take in only the ablest men, and they were supposed to be dedicated thus to be “leaders" in after life as well as at college. They took Bones with extreme solemnity. If the word “Bones” was spoken, they were supposed to have to leave the room, and it was said, I do not know how truly, that they could not relinquish their society pins even when they were taking a shower, at which time they had to hold them in their teeth. No Bones man, after college, was supposed to fail; his career in the larger world was intently followed by his brothers, and if he showed any signs of weakening, they arranged to prop him up.

Scott Fitzgerald once had the idea of bringing out the word “bones” in a Triangle Show, and then having two men dressed as tattered old bums get up and leave the theater. All of this side of Yale was, in general, the object of a good deal of kidding on the part of Harvard and Princeton, and the climax of the Yale song, "For God, for country and for Yale" was called the greatest anticlimax ever written. And yet I felt a certain respect for the importance given at Yale to intellectual achievement. Scholarship counted as well as athletics, and the editor of the Yale News and the editor of the Yale Lit were ex officio tapped for Bones. At Princeton, you had no incentive to excel in any such pursuit. ФВК had no prestige, was considered, in fact, rather second-rate, and I remember that I felt John Bishop had undergone a slight degradation when he found that he had earned this distinction and went to a ФВК dinner. In the years when he and I and Whipple and Hamilton Armstrong and Stanley Dell and Scott Fitzgerald and John Biggs were operating the Lit, we actually made a profit, and yearly "cut a melon" which afforded us $50 apiece. But this kind of thing you did on your own incentive and under your own steam. When you were faced with the lack of competition that followed election to a club and found that it involved nothing hut a comfortable place to eat, you had to keep your own fires stoked, and this was in some ways a very good thing. The pressure of Yale competition sometimes had the result of making the poets as well as the political and business types too eager for conspicuous success. And stimulating though I usually found the Bones men, I became aware, later on, when I shared an apartment with three Eli’s, and saw a good many of their friends, that unless you had fared well at Yale and were confidently headed for some substantial achievement, you were by no means a loyal son of Yale hut were likely to look hack on it with bitterness. A blistering instance of this was the speech made by Sinclair Lewis when he attended an alumni dinner. He said that in his years at Yale his classmates had paid no attention to him, had simply thought him a “sad bird,” as we said at Princeton. But now that he had had some success—publicity, reputation and money—they were making a fuss about him. The implication was that they could go to Hell. The Princetonians, on the other hand, had usually an affection for Princeton, which sometimes became quite maudlin. An uncle of mine—neither of those mentioned above— when he had already been some years out of Princeton, returned in tears to his brother’s house because Princeton had lost the big game. Examples of this childish loyalty— always, accompanied by extreme conservatism in regard to old college usages and by strong opposition to "liberal” ideas—still turn up in the correspondence columns of the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and I am glad to sec that the editor docs not encourage these outbursts but comments on them sometimes rather tartly. I used to note, on my visits to New Haven, that the dissipation at Yale was practised with the same earnestness as everything else, whereas the Yale men used to make fun of us for what they considered the childish namby-pambiness of "going to the Nass for a beer.” Yale was a burning religion, with, however, a good many unbelievers; Princeton a well-dressed and convivial group, to which, if one were not convivial, it was easy to remain indifferent.]

4. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

593 Summit Avenue St. Paul, Minnesota

September 26, 1917

From Turnbull.

Dear Bunny:

You'll be surprised to get this but it's really begging for an answer. My purpose is to see exactly what effect the war at close quarters has on a person of your temperament. I mean I'm curious to see how your point of view has changed or not changed—

I've taken regular army exams but haven't heard a word from them yet. John Bishop is in the second camp at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana. He expects a 1st Lieutenancy. I spent a literary month with him (July) and wrote a terrific lot of poetry mostly under the Masefield-Brooke influence.

Here's John's latest.

BOUDOIR

The place still speaks of worn-out beauty of roses,

And half retrieves a failure of Bergamotte,

Rich light and a silence so rich one all but supposes

The voice of the clavichord stirs to a dead gavotte

For the light grows soft and the silence forever quavers,

As if it would fail in a measure of satin and lace,

Some eighteenth century madness that sighs and wavers

Through a life exquisitely vain to a dying grace.

This was the music she loved; we heard her often

Walking alone in the green-clipped garden outside.

It was just at the time when summer begins to soften

And the locust shrills in the long afternoon that she died.

The gaudy macaw still climbs in the folds of the curtain;

The chintz-flowers fade where the late sun strikes them aslant.

Here are her books too: Pope and the earlier Burton,

A worn Verlaine; Bonheur and the Fetes Galantes.

Come—let us go—I am done. Here one recovers

Too much of the past but fails at the last to find

Aught that made it the season of loves and lovers;

Give me your hand—she was lovely—mine eyes blind.

Isn't that good? He hasn't published it yet. I sent twelve poems to magazines yesterday. If I get them all back I'm going to give up poetry and turn to prose. John may publish a book of verse in the spring. I'd like to but of course there's no chance. Here's one of mine.

TO CECILIA

When Vanity kissed Vanity

A hundred happy Junes ago,

He pondered o'er her breathlessly,

And that all time might ever know

He rhymed her over life and death,

“For once, for all, for love,” he said…

Her beauty's scattered with his breath

And with her lovers she was dead.

Ever his wit and not her eyes,

Ever his art and not her hair.

“Who'd learn a trick in rhyme be wise

And pause before his sonnet there.”

So all my words however true

Might sing you to a thousandth June

And no one ever know that you

Were beauty for an afternoon.

It's pretty good but of course fades right out before John's. By the way I struck a novel that you'd like, Out of Due Time by Mrs. Wilfred Ward. I don't suppose this is the due time to tell you that, though. I think that The New Machiavelli is the greatest English novel of the century. I've given up the summer to drinking (gin) and philosophy (James and Schopenhauer and Bergson).

Most of the time I've been bored to death— Wasn't it tragic about Jack Newlin? I hardly knew poor Gaily.1 Do write me the details.

I almost went to Russia on a commission in August but didn't so I'm sending you one of my passport pictures—if the censor doesn't remove it for some reason— It looks rather Teutonic but I can prove myself a Celt by signing myself

Very sincerely,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

1 Princetonians who died in the war.

BOUDOIR Later published in a different form in Bishop’s first book of poems, Green Fruit.

To CECILIA Later incorporated in a different form and set as prose in Book Two, Chapter III, of This Side of Paradise.

5. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

October 7, 1917

Grosse Pointe Farms, Mich.

Dear Fitz: I am quite unable to tell you what effect the war at close quarters has on a person of my temperament: I have never got any nearer to it than the Detroit state fairgrounds, where I am associated in the errand of mercy with the sorriest company of yokels that ever qualified as skillful plumbers or, an even less considerable eminence, received A.B. degrees from the University of Michigan, I waited till the middle of August to be called into camp and have now waited till October For the unit to sail for France. The ordeal has, it is true, been somewhat mitigated by having David Hamilton with me (I am at present writing from his house) and another friend From Yale; hut the latter has recently despaired of the hospital business and taken examinations for aviation and I have myself become so sterilized, suppressed, and blighted by two months of orderly, guard, and fatigue work that I am beginning to feel it wouldn't take much to make me do the same thing. Where is the old esprit and verve? I sometimes think it was finally extinguished the night when you and I sat alone upon the darkened and deserted verandah of Cottage (its marble splendors more desolate untenanted than were ever the stinking halls of Commons when Princeton was alive) and let John Bishop take the shabby whoring of the Princeton streets for the royal harlotries of Rome and the Renaissance. Ah, how not only, to quote your friend, are the beautiful broken and the swiftest made slow, but the kindly made hard and the clever made dull! Seriously, I shall never forget that ghastly evening; I have never seen or heard from John and was consequently glad to get his poem, which is excellent, of course, except for the last stanza, which does seem to me inadequate. I like yours, too, although I didn't understand the two quoted lines in the last stanza, and ever since “Princeton: The Last Day,” which, if it means what I think it does, possesses a depth and dignity of which I didn't suppose you capable, have thought you by way of becoming a genuine poet. If you have my more stuff of John's and your own, I wish you would send it along; my comrades of the unit make it seem to me incredible that I could ever have had friends who spent ecstatic hours pursuing the Beautiful. And if you have any news of Alec or Townsend, I should he exceedingly glad to hear it. You speak of Jack Newlin, but I have never heard nothing about him; has he been killed?

I'm inclined to agree with you about The New Machiavelli [H. G. Wells], at least so far as to admit that it is one of the best novels of the century. By the way, you should read James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which is probably another of the best novels of the century, and also an essay called “British. Novelists, Ltd” by Mrs. [Katharine Fullerton] Gerould in the last Yale Review. I wonder what will happen to the Lit. Will it be compelled to subsist for a while as a memory merely on the strength of the brilliant past which you and John and Teek and I and the rest have just supplied? When I read a few fragments of platitude reprinted in The Evening Post from Mr. Hibben's* speech at the opening of the university I avert my inward gaze from a crippled Princeton which I have no more tears to weep and turn them back to the contemplation of a wretched world which, for all the men I may damage or repair in the service of the country, I know I can do little or nothing to correct and heal. Although the truth is I have almost forgotten about the war, since I have become a member of the army. It has reached such an impasse, since the rejection of the Pope's appeal, that it only exasperates one to try to figure a solution. And if my letter is arid it is only because I am arid myself at the moment as I hope never to be again; but still remain, in the sacred name of the divine muses and the indissoluble bond of our knocked-up alma mater,

“Because her bells are clearer than the guns;

Because her books are braver than the charge'

(to quote the lines of a great but temporarily neglected poet).

Yours for what you choose to consider the Celtic strain in us and which, whatever it is, for all our laziness and ignorance, does separate from the optimistic and sentimental mass of our countrymen, in company with yourself,

Edmund Wilson, Jr.

You will pardon the effects of this vile stub pen.

Notes:

* “The president of Princeton in my time was John Grier Hibben…”

6. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

Fall 1917

ALS, 6 pp. Yale University; From Turnbull, Life In Letters.

Cottage Club

Princeton, N.J.

Dear Bunny:

I’ve been intending to write you before but as you see I’ve had a change of scene and the nessesary travail there-off has stolen time.

Your poem came to John Biggs, my room mate, and we’ll put in the next number—however it was practically illegable so I’m sending you my copy (hazarded) which you’ll kindly correct and send back——

I’m here starting senior year and still waiting for my commission. I’ll send you the Litt. or no—you’ve subscribed haven’t you.

Saw your friend Larry Noyes in St. Paul and got beautifully stewed after a party he gave—He got beautifully full of canned wrath—I dont imagine we’d agree on much——

Do write John Bishop and tell him not to call his book “Green Fruit.”

Alec is an ensign. I’m enclosing you a clever letter from Townsend Martin which I wish you’d send back.

Princeton is stupid but Gauss + Gerrould are here. I’m taking naught but Philosophy + English—I told Gauss you’d sailed (I’d heard as much) but I’ll contradict the rumor.

The Litt is prosperous—Biggs + I do the prose——Creese and Keller (a junior who’ll be chairman) and I the poetry. However any contributions would be ect. ect.

Have you read Well’s “Boon; the mind of the race” (Doran—1916) Its marvellous! (Debutante expression. Young Benet (at New Haven) is getting out a book of verse before Xmas that I fear will obscure John Peale’s. His subjects are less Precieuse + decadent. John is really an anachronism in this country at this time—people want ideas and not fabrics.

I’m rather bored here but I see Shane Leslie occassionally and read Wells and Rousseau. I read Mrs. Geroulds “British Novelists Limited + think she underestimates Wells but is right in putting Mckenzie at the head of his school. She seems to disregard Barry and Chesterton whom I should put even above Bennet or in fact anyone except Wells.

Do you realize that Shaw is 61, Wells 51, Chesterton 41 Leslie 31 and I 21. (Too bad I havn’t a better man for 31. I can hear your addition to this remark).

Oh and that awful little Charlie Stuard (a sort of attenuated Super-Fruit) is still around (ex ’16—now 17/). He belongs to a preceptorial where I am trying to demolish the Wordsworth legend—and contributes such elevating freshman-cultural generalities as “Why I’m suah that romantisism is only a cross-section of reality Dr. Murch.”

Yes—Jack Newlin is dead—killed in ambulance service. He was, potentially a great artist

Here is a poem I just had accepted by “Poet Lore”

The Way of Purgation

A fathom deep in sleep I lie

With old desires, restrained before;

To clamor life-ward with a cry

As dark flies out the greying door.

And so in quest of creeds to share

I seek assertive day again;

But old monotony is there—

Long, long avenues of rain.

Oh might I rise again! Might I

Throw off the throbs of that old wine—

See the new morning mass the sky

With fairy towers, line on line—

Find each mirage in the high air

A symbol, not a dream again!

But old monotony is there—

Long, Long avenues of rain.

No—I have no more stuff of Johns—I ask but never recieve

If Hillquit gets the mayoralty of New York it means a new era. Twenty million Russians from South Russia have come over to the Roman Church. [In the margin:] news jottings (unofficial).

I can go to Italy if I like as private secretary of a man (a priest) who is going as Cardinal Gibbons representative to discuss the war with the Pope (American Catholic point of view—which is most loyal—barring the SienFien—40% of Pershing’s army are Irish Catholics. Do write.

Gaelicly Yours

Scott Fitzgerald

I remind myself lately of Pendennis, Sentimental Tommy (who was not sentimental and whom Barry never understood) Michael Fane, Maurice Avery + Guy Hazelwood)

Notes:

Wealthy Princeton classmate of Fitzgerald’s later a movie writer and producer.

Professors Christian Gauss and Gordon Hall Gerould.

Poet Stephen Vincent Benet, then a Yale undergraduate.

Katharine Fullerton Gerould, Yale Review (October 1917).

Compton Mackenzie, James M. Barrie, G. K. Chesterton, Arnold Bennett, H. G. Wells—contemporary British novelists.

This poem was not published by Poet Lore.

Father Cyril Sigourney Webster Fay had befriended Fitzgerald at the Newman School. He was the model for Monsignor Darcy in This Side of Paradise.

Characters in novels by William Makepeace Thackeray, Barrie, and Mackenzie.

THE WAY OF PURGATION This poem in slightly different form and without the title appears at the beginning of Book Two, Chapter V, of This Side of Paradise."

7. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

December 3, 1917

France

Dear Fitz: Your letter has just reached me; thank you for Townsend's letter; I can almost hear him talking, I should make haste to do anything in my power to dissuade John from calling his poems Green Fruit, but do not know his address, having heard nothing from him. I wish you would let me know where he is and whether he got his commission. Ask him to drop me a line.

I cannot even yet tell you much about war at close quarters, being only near enough to hear the guns, which do not sound as loud as thunder. We are stationed in what was once a popular summer resort* hut has now been turned over to the American hospital service, which is going to turn the hotels into hospitals. It will he at least three months before they are ready to receive patients and I have decided, in the meantime, to resume the writing of my forthcoming books, war or no war. If I did not do this, I think I should die of my own futility? and a growing conviction of the futility of prolonging the war; this last fostered lately by Lord Landsdowne's letter, Bernard Shaw's last public speech, the Russian armistice and the Italian defeat and, also on being nourished by [Romain] Holland's Au-dessus de la melee, France's L'Orme du mail, and that fine series of ironies at the expense of the Franco-Prussian War: Les Soirees de Medan.

But the chief thing really is the terrible silence and weariness of this pan of France. Our life here, with its round of marvelous French dinners at little cafes and of walks and bicycle rides to the ancient villages that are all around us, would be perfectly idyllic, if it were not for the fact that the unseen, unrealized reality of the war and one's own prolonged inactivity makes it more ghastly than you can believe. Over such wine and food as this, we could once (Dave and I—and you and the rest, if you were here) have outworn and outdazzled the stars with the sparks of our jesting, but I feel that the door of the house of mirth and, in fact, of any normal occupation is shut till the war is over. Not that we don't hold revelry here of no mean order! David, a newspaperman from Harvard, an extremely amusing and nice artist, and myself are accustomed to consort together in the back rooms of cafes, restaurants, bistros, quinquettes, buvettes, and claquedents of every sort and drink with an enthusiasm verging on ferocity to the eternal damnation of the army. But all this is a revelry stunned and distraught, Christmas dinner among the convicts, the Black Mass performed by marionettes . . .

It somehow reassures me that you should be back at Princeton, as if, after all, the continuity of life there had nut quite been broken up. Remember me to Gauss: I think of him often in France, In spite of the fact that I had been here before, years ago, it was chiefly because of what he had taught me that I felt so little a stranger when I arrived here a couple of weeks ago.

Yours always, Edmund Wilson, Jr.

Notes:

* “We were stationed at Vittel in the Vosges…” —A Prelude

8. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

ALS, 4 pp. Yale University; From Turnbull, Life In Letters.

Jan 10th, 1917. [1918]

Dear Bunny:

Your last refuge from the cool sophistries of the shattered world, is destroyed!—I have left Princeton. I am now Lieutenant F. Scott Fitzgerald of the 45th Infantry (regulars.) My present adress is

Co Q

P.O.B.

Ft. Leavenworth

Kan.

After Feb 26th

593 Summit Ave

St. Paul

Minnesota

will always find me forwarded

—So the short, swift chain of the Princeton intellectuals (Brooke’s clothes, clean ears and, withall, a lack of mental prigishness … Whipple, Wilson, Bishop, Fitzgerald … have passed along the path of the generation—leaving their shining crown apon the gloss and un worthiness of John Biggs head.

One of your poems I sent on to the Litt and I’ll send the other when I’ve read it again. I wonder if you ever got the Litt I sent you … so I enclosed you two pictures, well give one to some poor motherless Poilu fairy who has no dream. This is smutty and forced but in an atmosphere of cabbage …

John’s book came out in December and though I’ve written him rheams (Rhiems) of praise, I think he’s made poor use of his material. It is a thin Green Book.

Green Fruit

(One man here remarked that he didn’t read it because Green Fruit always gave him a pain in the A——!)

by

John Peale Bishop

1st Lt. Inf. R.C.

Sherman French Co

Boston.

In section one (Souls and Fabrics) are Boudoir, The Nassau Inn and, of all things, Fillipo’s wife, a relic of his decadent sophmore days. Claudius and other documents in obscurity adorn this section.

Section two contains the Elspeth Poems—which I think are rotten. Section three is (Poems out of Jersey and Virginia) and has Cambell Hall, Mellville and much sacharine sentiment about how much white bodies pleased him and how, nevertheless he was about to take his turn with crushed brains (this slender thought done over in poem after poem). This is my confidential opinion, however; if he knew what a nut I considered him for leaving out Ganymede and Salem Water and Francis Thompson and Prayer and all the things that might have given some body to his work, he’d drop me from his writing list. The book closed with the dedication to Townsend Martin which is on the circular I enclose. I have seen no reviews of it yet.

The Romantic Egotist

by

F. Scott Fitzgerald

“… The Best is over

You may complain and sigh

Oh Silly Lover…”

Rupert Brooke

“Experience is the name Tubby gives to his mistakes…

Oscar Wilde

Chas. Scribners Sons (Maybe!)

MCMXVIII

There are twenty three Chapters, all but five are written and it is in poetry, prose, vers libre and every mood of a tempermental temperature. It purports to be the picaresque ramble of one Stephen Palms from the San Francisco fire, thru School, Princeton to the end where at twenty one he writes his autobiography at the Princeton aviation school. It shows traces of Tarkington, Chesteron, Chambers Wells, Benson (Robert Hugh), Rupert Brooke and includes Compton-Mckenzie like love-affairs and three psychic adventures including one encounter with the devil in a harlots apartment.

It rather damns much of Princeton but its nothing to what it thinks of men and human nature in general. I can most nearly describe it by calling it a prose, modernistic Childe Harolde and really if Scribner takes it I know I’ll wake some morning and find that the debutantes have made me famous over night. I really believe that no one else could have written so searchingly the story of the youth of our generation…

In my right hand bunk sleeps the editor of Contemporary Verse (ex) Devereux Joseph, Harvard ’15 and a peach—on my left side is G. C. King a Harvard crazy man who is dramatizing “War and Peace”; but you see Im lucky in being well protected from the Philistines.

The Litt continues slowly but I havn’t recieved the December issue yet so I cant pronounce on the quality.

This insolent war has carried off Stuart Walcott in France, as you may know and really is beginning to irritate me—but the maudlin sentiment of most people is still the spear in my side. In everything except my romantic Chestertonian orthodoxy I still agree with the early Wells on human nature and the “no hope for Tono Bungay” theory.

God! How I miss my youth—thats only relative of course but already lines are beginning to coarsen in other people and thats the sure sign. I dont think you ever realized at Princeton the childlike simplicity that lay behind all my petty sophistication, selfishness and my lack of a real sense of honor. I’d be a wicked man if it wasn’t for that and now thats dissapearing…

Well I’m over stepping and boring you and using up my novel’s material so good bye. Do write and lets keep in touch if you like.

God Bless You

Celticly

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Bishop’s adress

Lieut. John Peale Bishop (He’s a 1st Lt.)

334th Infantry

Camp Taylor

Kentucky

Notes:

T. K. Whipple became a literary critic.

Booth Tarkington, G. K. Chesterton, Robert W. Chambers, H. G. Wells, and Robert Hugh Benson were contemporary novelists; Rupert Brooke was a young British poet killed in World War I.

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812–1818) was a partially autobiographical heroic poem by George Gordon Byron, Lord Byron.

H. G. Wells’s novel Tono-Bungay (1909) portrayed the corruption of English society.

world, is destroyed - I had graduated from college in 1916 and had written him from France that my last solace was to think of those of our literary group who were still at Princeton. E.W. in The Crack-Up

enclosed you two pictures - I had mentioned in my reply to his previous letter that he had enclosed two prints of his passport picture. E.W. in The Crack-Up

9. FROM: John Peale Bishop1 , To Fitzgerald

January 1918

ALS, 5 pp. Princeton University; From Correspondence.

O God! O God! How wonderful Youth's Encounter is! Perhaps it meant more to me now than it would have done at Princeton, but it has done more than all the sociology in the world to make me feel life is worth living. I rose from its reading with that “free” feeling you have when the first thaw of spring takes the courses of winter. What if the light is too golden, the half-light too blue? Who would have them otherwise in a story of youth is an ass and the father of asininity. This is undoubtedly the true, the undefiled aim of the novel—to present—but how shall I venture to speak to your ears, so fearful of banalities?—any how it's not sociology. That's the chief difference between the French and the English novel—the typical French and English novel. There's no preachment in the former.

Now to come to your own book.2 Scott, I think if you will recollect the volume above, or the account of Wells' youthful heroes, or Anatole France's he Livre de Mon Ami, the glaring defect of your book will be noted. I have a theory that novels as well as plays should be in scenes. The marvellous effect of Crime and Punishment is largely due to the cumulative effect of the successive climaxes. Each scene—chapter what you will should be significant in the development either of the story or the hero's character. And I don't feel that yours are. You see Stephen3 does the things every boy does. Well and good. I suppose you want the universal appeal. But the way to get it is to have the usual thing done in an individual way. You don't get enough into the boy's reactions to what he does. Its the only way to awaken the memory which is the real source of pleasure in boy's stories for grown-olds. It's not in relating what a boy does that causes this awakening, but his own love in what he does. Think of Michael Fane's reaction to the iron bars of his crib. It's wonderful. Now your boy sleds, but I don't feel that he enjoys sledding. In matter of fact, I don't realize fully that he does sled. You see what I mean? Each incident must be carefully chosen—to bring out the typical: then ride it for all its worth.

You see I don't know what Stuart's4 like. I don't feel the charm of Stephen's childish harem. While with Michael I successively fell just as deeply in love with Dora, Kathleen, and Lily as he did. You have got to be more leisurely. Fill out the setting. Make each incident a step. The successive chapters should be in echelon, each a step and yet all clear at once.

I have been pretty miserable lately, but today feel fairly like I'd prefer to keep living.

I'm thinking seriously of writing a novel myself. I have a room now— shared with one other man who is [not there] a great deal. I certainly can't write poetry.

Did I refer to the 45th Inf. again? Well, what I meant was that it was full of recruits and wouldn't be fit for foreign service for quite a while— That's nothing against it. It will probably give you better treatment than we get here. I am wild with rage over this last measure—All officers attend reveille—600 A.M. O ye gods of the petit dejeuner! It takes an act of congress to make gentlemen out of us. No body would ever suspect it from the life you lead. Being an attached lieutenant is almost as bad as being a T.C. Candidate. Except for the social idea, I'd as soon be a sergeant. When do you come down? ANSWER THAT.

You certainly shat on my poem. Well, its not very good, but Bunny5 liked it, so I chucked it in.6 That last section has a good deal of drule. Endymion, Sylvo and Nassau Street are all right, but the rest are bum.

However, I don't think you have any right to compare it to R.B.7 Nassau Street would be a fairer comparison. But you can't refer to his uplift, because our situation was so utterly different. Everybody felt it in England, but less because of the war than because of the frightful state England was in when war came. Decadent boredom and futile political wrangling. You damn well, nobody felt any lift at Princeton. And somehow, I've never reacted emotionally to the war. I am beginning to feel a fine hatred, if you will, but my chief emotion last spring was regret at seeing the fellows go and all that went into the last of Nassau Street. It was a banal emotion—we've discussed that before.

Adieu. St James of Compostella.

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald's Princeton classmate who became the model for Thomas Parke D'Invilliers in This Side of Paradise.

2 “The Romantic Egoist.”

3 The hero of Fitzgerald's novel in progress was named Stephen Palms.

4 A character in “The Romantic Egoist.”

5 Edmund Wilson, Jr.

6 Bishop had published Green Fruit (1917), a volume of verse.

7 Rupert Brooke.

10. Jan 1918. [Fragment] From J. P. Bishop

Bishop wrote ...even death there would be a compensation - Keats, Shelley, Browning, Wilde, Bishop various and gifted quintet, let us weep over all five...

11. Jan 1918. [Fragment]

And Fitzgerald responded:

12. FROM: John Peale Bishop, To Fitzgerald

January 1918

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University; From Correspondence.

Now as to the book—The new chapters are much, much better. You didn't get the small boy's viewpoint very well. The schoolboy is far better done. I am beginning to know Stephen better, but I feel you are concealing a great deal of the young man's history that I ought to know. And it's just for this reason that I don't particularly like him. You see he isn't popular and on the whole one feels rather deservedly; you have been too hard on him and your reader is rather easily prejudiced against him. Why don't you give the other side. Show the boy's loneliness, his real suffering when alone, his mental and emotional states. The history is not subjective enough. I cant make that too strong. That's when the immense superiority of Youths Encounter comes in. You give us the acts of the boy. Mackenzie the mind and soul moving through the action. No body is particularly interested in what small boys do—except their individual parents—but we all love to recapture their attitude toward the world. In a way, it's the most mysterious thing in the world. To a grown man, woman is comparitively simple as against the adolescent youth. It apparently means nothing that we have been through it. It is exceedingly difficult to regain that curious mental life which is not rational, not clear, and uncolored by real emotion. It is the result of the beginning of clear reasoning and the uprising of the thousand obscure complexities of sex which permeate everything yet never identify themselves definitely with the sexual function That's my first criticism and the second is a further plea for simplification. Don't put in everything you remember. Retain only significant events and ride them hard. Pad them with Stephen's reactions. That's the great trouble with autobiographical material, it's so hard to arrange, so hard to distinguish as regards the incidental and the essential.

Send on more copy.

I haven't heard of the 45th going away.

One face than autumn lilies tenderer

And voice more soft than the far plaint of viols is

Or the soft moan of any grey-eyed lute player

—Heard the strange lutes on the green banks

Ring loud with grief and delight

Of the sun-silked, dark haired musicians

In the brooding silence of night.

O western winds when will ye blow

That the small rain down can rain.

Christ! that my love were in my arms

And I in my bed again.

Till life us do part

Casabianca.

13. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

August 9, 1919

Red Bank

Dear Scott: I have heard various rumors about you since I have been back (I landed July 2), but can't seem to find out where you are now. I suppose you must be in St. Paul. I move up to the city tomorrow where I have an apartment (114 West Twelfth Street) with Larry Noyes and others. When you come to New York again, be sure to look me up and, in the meantime, drop me a line.

Stan Dell and I have conceived a literary project In which you might possibly help us. Our idea is to write a new Soirees de Medan on the American part in the war. The original Soirees de Medan was a set of short stories published after the Franco-Prussian War by a group of realistic writers headed by Zola (Zola, Maupassant, Huysmans, etc.). Our problem is to get enough other people to contribute besides ourselves, and I have written to John Bishop and a number of others. These stories don't all of them have to deal with the fighting proper, of course, One of the remarkable virtues of the Soirees was the fact that they dealt not only with the front but also with the mismanagement of the war by the government, the effect on the civilian population, and the stagnation of the troops behind the lines. You never got abroad, but tant mieux! let us have something about army life in the States during the war. I know that your line isn't the Zola-Maupassant genre, but I'm sure you ought to be able to produce something illuminating. No Saturday Evening Post stuff, understand! clear your mind of cant! brace up your artistic conscience, which was always the weakest part of your talent! forget for a moment the phosphorescences of the decaying Church of Rome! Banish whatever sentimentalities may still cling about you from college! Concentrate in one short story a world of tragedy, comedy, irony, and beauty!!! I await your manuscript with impatience.

I'm sorry to hear that you were disappointed about your novel; I should like to see it. And you must write another someday, in any case.

Yours always, Edmund Wilson, Jr.

14. To F. Scott Fitzgerald [Postcard], From Edmund Wilson

August 14, 1919

114 West Twelfth Street, NX

I'm glad you've got a foothold with Scribner's. Don't worry about me: I'm not writing a novel, but I'm writing almost everything else, and getting some of it accepted. I hope your letter isn't a fair sample of your present literary methods: it looks like the attempt of a child of six to write F.P.A.'s [Franklin P. Adams] column. Send along your story, when you get to it.

E.W.

I don't think any of your titles are any good.

John Bishop hasn't arrived yet as far as I know.

15. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

ALS, 4 pp. Yale University; From Turnbull, Life In Letters.

599 Summit Ave

St. Paul, Minn

August 15th [1919]

Dear Bunny:

Delighted to get your letter. I am deep in the throes of a new novel. Which is the best title

(1) The Education of a Personage

(2) The Romantic Egotist

(3) This Side of Paradise

I am sending it to Scribner—They liked my first one. Am enclosing two letters from them that migh t’amuse you. Please return them.

I have just the story for your book *. Its not written yet. An American girl falls in love with an officier Francais at a Southern camp.

Since I last saw you I’ve tried to get married + then tried to drink myself to death but foiled, as have been so many good men, by the sex and the state I have returned to literature

Have sold three or four cheap stories to Amurican magazines.

Will start on story for you about 25th d’Auout (as the French say or do not say), (which is about 10 days off)

I am ashamed to say that my Catholoscism is scarcely more than a memory—no that’s wrong its more than that; at any rate I go not to the church nor mumble stray nothings over chrystaline beads.

May be in N’York in Sept or early Oct.

Is John Bishop in hoc terrain?

Remember me to Larry Noyes. I’m afraid he’s very much off me. I don’t think he’s seen me sober for many years.

For god’s sake Bunny write a novel + don’t waste your time editing collections. It’ll get to be a habit.

That sounds crass + discordant but you know what I mean.

Yours in the Holder ** group

F Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

* Wilson was trying to get together a collection of realistic stories about the war.

** Holder Hall, Princeton University dormitory.

16. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

599 Summit Avenue St. Paul, Minnesota

[Probably September, 1919]

From Turnbull.

Dear Bunny:

Scribners has accepted my book for publication late in the winter. You'll call it sensational but it really is neither sentimental nor trashy.

I'll probably be East in November and I'll call you up or come to see you or something. Haven't had time to hit a story for you yet. Better not count on me as the w. of i. or the E.S. are rather dry.

Yrs. faithfully, Francis S. Fitzgerald

17. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

November 21, 1919

114 West Twelfth Street, N.Y.

Dear Fitz: I have just read your novel with more delight than I can well tell you.* It ought to be a classic in a class with The Young Visiters.** Amory Blaine should rank with Mr. Salteena. It sounds like an exquisite burlesque of Compton Mackenzie with a pastiche of Wells thrown in at the end. I wish you hadn't chosen such bad masters as Mackenzie and the later Wells: your hero is an unreal imitation of Michael Fane, who was himself unreal and who was last seen in the role of the veriest cardboard best-seller hero being nursed back to life in the Balkans. Almost the only things of value to be learned from the Michael Fane books are pretty writing and clever dialogue and with both of these you have done very well. The descriptions in places are very nicely done and so is some of the college dialogue, which really catches the Princeton tone, though your hero as an intellectual is a fake of the first water and I read his views on art, politics, religion, and society with more riotous mirth than I should care to have you know. You handicap your story, for one thing, by making your hero go to the war and then completely leaving the war out. If you thought you couldn't deal with his military experiences, you shouldn't have had him go abroad at all. You make him do a lot of other things that the real Amory never did, such as getting on The Prince and playing on the football team, and thereby you produce an incredible monster, half romantic hero and half F. Scott Fitzgerald. This, of course, may be more evident to me than it would be to some reader who didn't know you, but I really think you should cultivate detachment and not allow yourself to drift into a state of mind where, as in the latter part of the book, you make Amory the hero of a series of dramatic encounters with all the naive and romantic gusto of a small boy imagining himself as a brave hunter of Indians. The love affairs seem to me the soundest part of the book as fiction; the ones with Isabelle and Rosalind are the realest. I was, of course, infinitely entertained by the Princeton part: but you put in some very dubious things—the party at Asbury Park, for example, where they beat their way through the restaurants. If you tell me that you have seen this happen, I point to the incident in which the Burne brothers, who are presumably not supposed to he cads, are made to play an outrageous and impossible practical joke on the girl who comes down for the game. I was also very much shocked when poor old John Bishop's hair stands up on end at beholding the Devil.

I don't want to bludgeon you too brutally, however, for I think that some of the poems and descriptions are really exceedingly good. It would all be better if you would tighten up your artistic conscience and pay a little more attention to form. Il faut faire quelque chose de vraiment beau, vous savez! something which the world will not willingly let die! I feel called upon to give you this advice because I believe you might become a very popular trashy novelist without much difficulty.

The only first-rate novel recently produced in this genre is James Joyce's hook and that is one of the best things in English because of its rigorous form and selection and its polished style and because the protagonist is presented with complete detachment, with the ugly sides of his life as accurately depicted as the inspired and beautiful ones. But what about the ugly and mean features of Amory's life! You make some feeble attempts to account for them in the beginning, but on the whole your hero is a kind of young god moving among demi-gods; the Amory I hear about in the book is not the Amory I knew at Princeton, nor at all like any genuine human being I ever saw. Well, I concede that it is much better to imagine even a more or less brummagem god and strike off from him a few authentic gleams of poetry and romance than to put together a perfectly convincing and mediocre man who never conveys to the reader a single thrill of the wonder of life, like Beresford's Jacob Stahl and a lot of other current heroes, but I do think the most telling poetry and romance may be achieved by keeping close to life and not making Scott Fitzgerald a sort of super-Michael Fane. Cultivate a universal irony and do read something other than contemporary British novelists: this history of a young man stuff has been run into the ground and has always seemed to me a bum art form, anyway, at least when, as in Beresford's or Mackenzie's case, it consists of dumping all one's youthful impressions in the reader's lap, with a profound air of importance. You do the same thing: you tell the reader all sorts of stuff which has no tearing on your story and no other interest—that detail about how Amory's uncle gave him a cap, etc.

I really like the hook, though; I enjoyed it enormously, and I shouldn't wonder if a good many other people would enjoy it, too. You have a knack of writing readably which is a great asset, Your style, by the way, has become much sounder than it used to be. Well, I hope to see you here soon. Thanks for the novel.

Yours always, Edmund Wilson, Jr.

Notes:

* This Side of Paradise.

** A novel by Daisy Ashford, purporting to be written by a pre-adolescent English girl.

18. FROM: John Peale Bishop, To Fitzgerald

18 December 1919

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University; From Correspondence.

Dear Scott,

The most poetic thing in the novel is the Title—couldn't be better.

The most original character is Eleanor.

The best incident is the dramatic interlude at Alec's house.

The most realistic bit is the drunk.

The most amusing character is Tanaduke.

The best poem is “When Vanity kissed Vanity”

The cleverest poem is from Boston Bards and Hearst Reviewers.

The best-written part is the last.

The most unconvincing character is Amory's mother.

“ ” ” incident is that with Ferrenby's father.

But it's damn good, brilliant in places, and sins chiefly through exuberance and lack of development.

I have been offered a job to go back to Europe for a year at $2800, but shan't take it if Scribner's comes through, and I think they will. I wish I could go up and just write but I am too poor. And I can't write here. Alec1 and I are going to live together. I am throwing out several poems a day and have started a story. The idea is a knock-out, but I doubt my ability to handle it. I enclose two poems, for your criticism.

When are you to be married? When are you coming to New York?

John

Notes:

1 Alexander McKaig, Princeton '17.

19. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

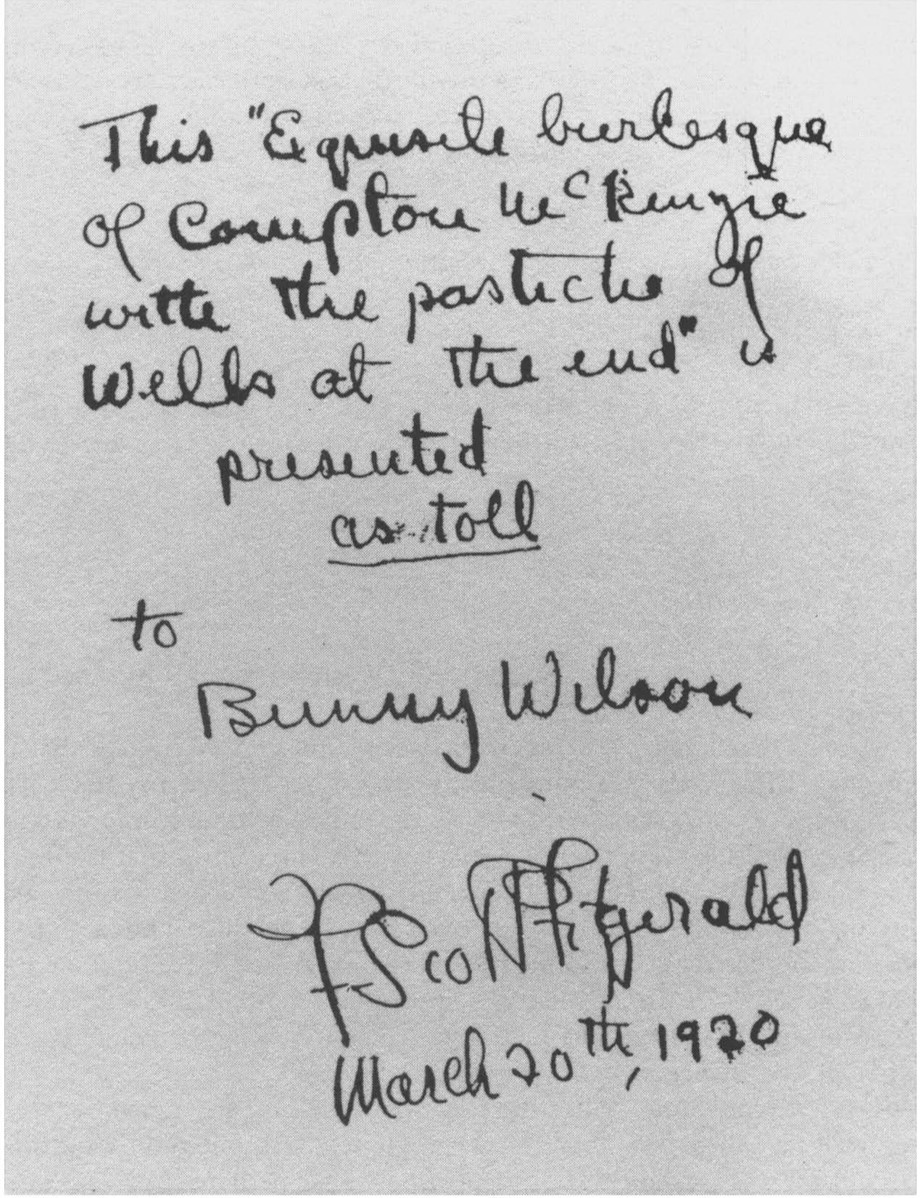

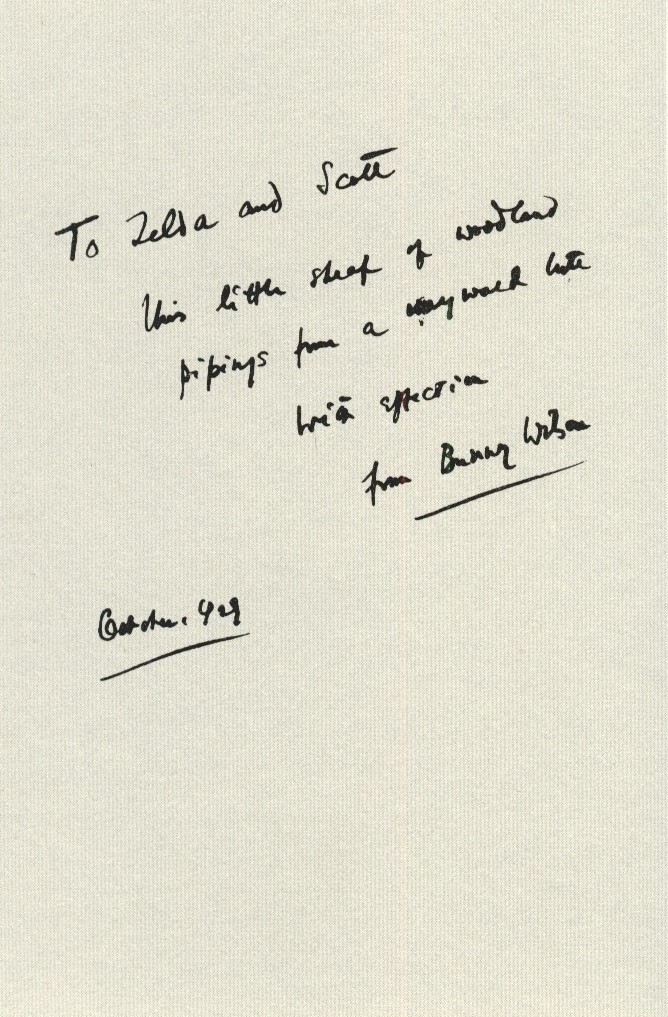

Inscription in This Side of Paradise (published on April 20, 1920)

University of Tulsa Library, New York City

This “Exquisite burlesque of Compton McKenzie with the pastiche of Wells at the end” is presented as toll to Bunny Wilson

F. Scott Fitzgerald

March 20th, 1920

Notes:

Fitzgerald's description of This Side of Paradise is quoted from Wilson's letter.

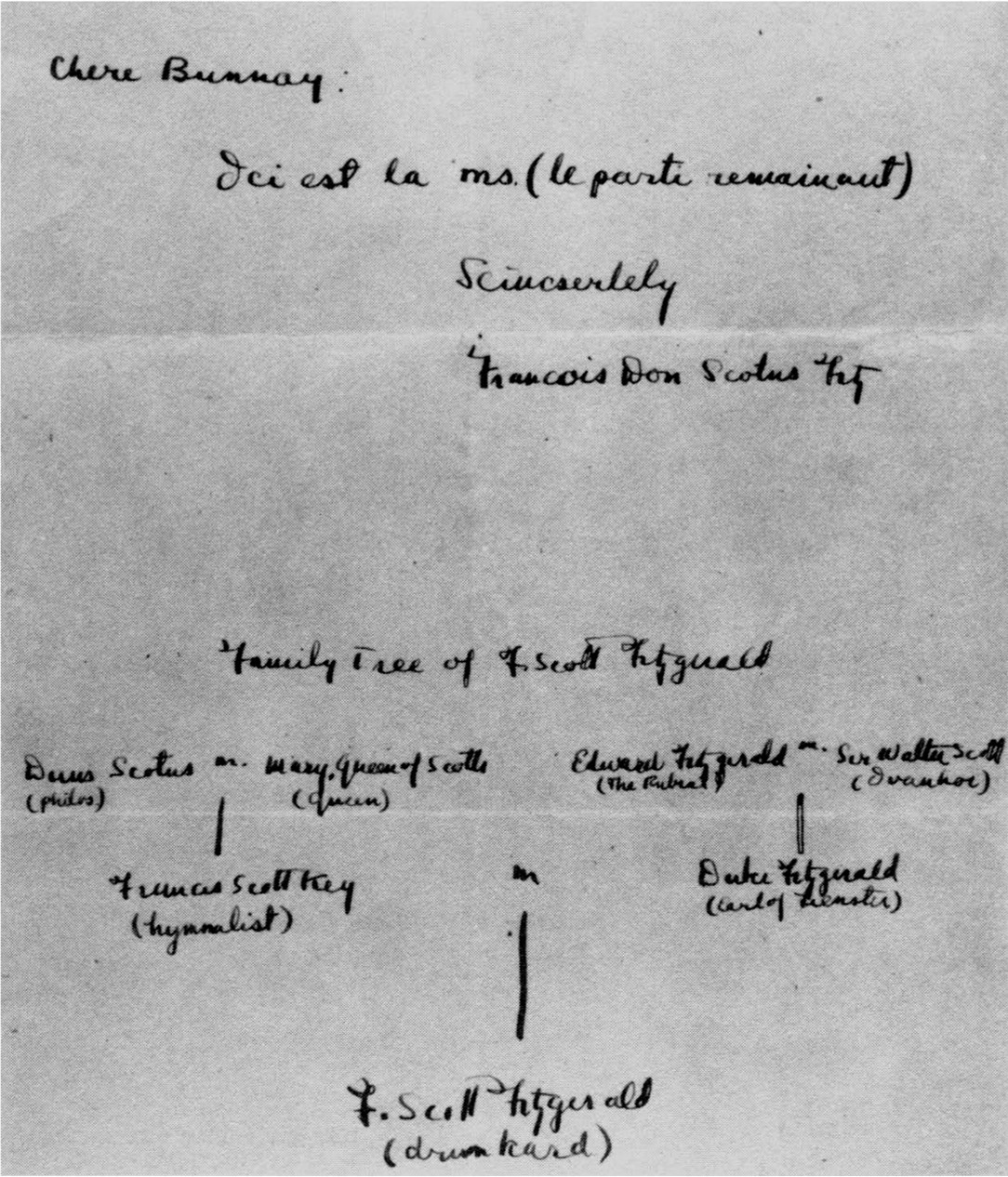

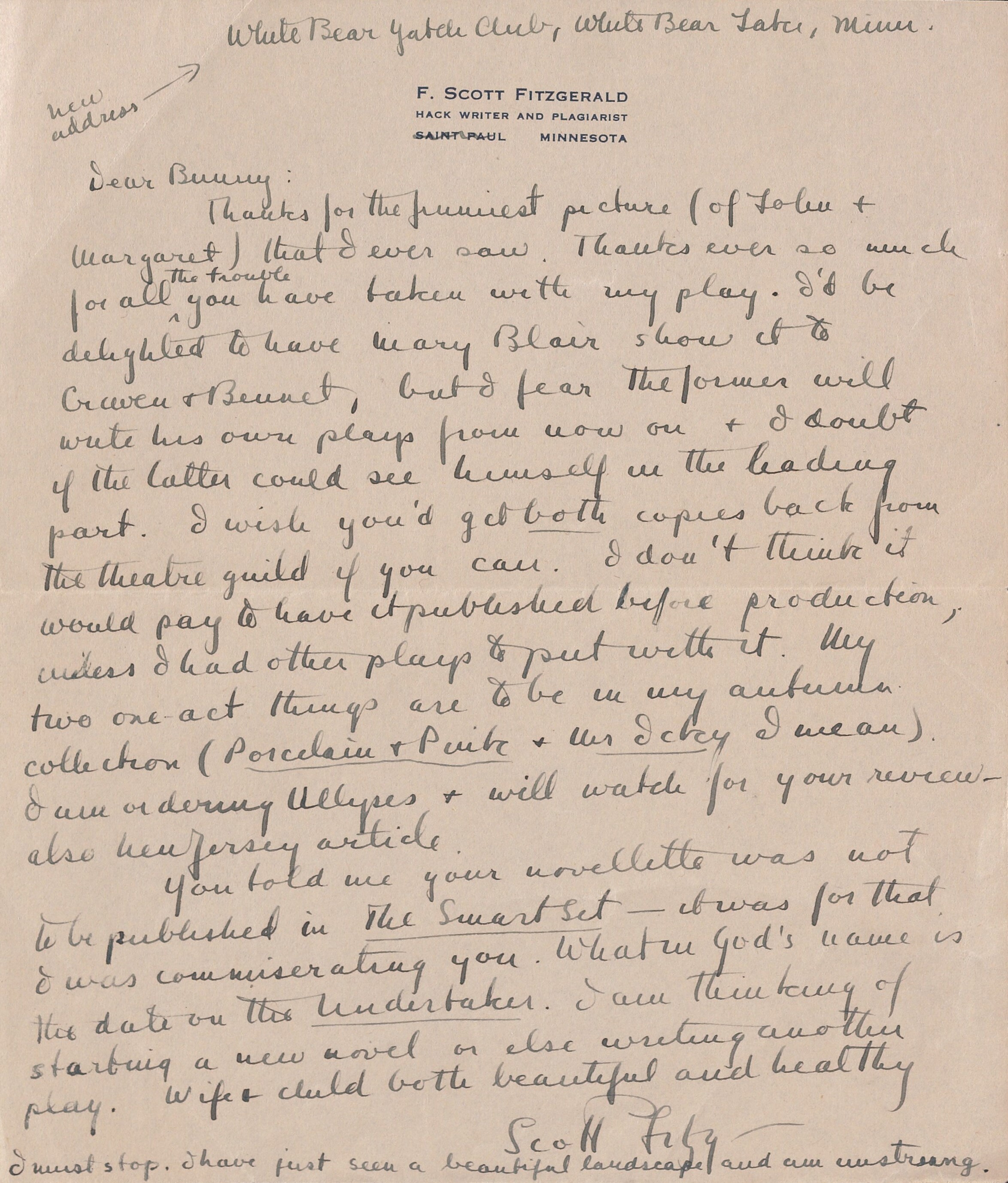

20. To Edmund Wilson

ALS, 1 p., Yale Univercity, New York City

December 1920

Chere Bunnay

Ici est la ms (le parte remainant)

Scincserlely,

Francois Don Scotus Fitz

Family tree of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

...

Notes:

The manuscript enclosed was either "This Is a Magazine" or "Jemina, The Mountain Girl" (both were published in Vanity Fair, Dec'20 or Jan'21, corresp.)

21. To Christian Gauss, From Edmund Wilson

April 28, 1920

Vanity Fair

Dear Mr. Gauss: Fitz is in town, at the Hotel Commodore. I have just had a telephone conversation with him. He said that he had left Princeton in disgrace and was ashamed to go back, but when I told him we wanted him for the dinner, he said that he would like to go down with John [Peale Bishop] and me and come back immediately afterwards. I hounded him about speaking and he protested that he couldn't speak except when under the influence and that he didn't want to get drunk on this occasion. I think he will he fairly tame, because he is going to leave Zelda at the Commodore; I trust that she will seize the opportunity to run away with the elevator boy or something.

I have written to Kean Wallis, but not to Teek Whipple; I understood that the committee would notify him. That's right, isn't it? John Bishop says he will speak. Besides him and Fitz, Stanley Dell, Townsend Martin, and Hardwick Nevin are surely coming,

Yours always, EW

22. [Fragment] To Stanley Dell, From Edmund Wilson

February 19, 1921

Vanity Fair

… I am editing the MS of Fitz's new novel* and, though I thought it was lather silly at first, I find it developing a genuine emotional power which he has scarcely displayed before. I haven't finished it yet, though, so can't tell definitely. It is all about him and Zelda…

Notes:

* The Beautiful and Damned

23. TO: Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

February 1921

New York City

ALS, 1 p. Yale University; From Correspondence

Dear Bunny:

The kind of critisism1 I'd like more than anything else—if you find you have the time, would be; par example

P. 10x I find this page rotten

P. 10y Dull! Cut!

P. 10z Good! enlarge!

P. 10a Invert sentence I have marked (in pencil!)

P. 10b unconvincing!

P. 10c Confused!

***

Ha-ha!

***

I'm glad you're going to the New Republic. It always seemed undignified for you to be on Vanity Fair.

F. Scott Fitz—

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald had probably given Wilson a working draft of The Beautiful and Damned.

24. [Fragment] To Christian Gauss, From Edmund Wilson

March 1, 1921

The New Republic

… Fitz's new novel, which I have been editing, is admirable, much the best thing he has done; it is all about his married life …

25. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

July 1921

ALS, 6 pp. Yale University; From Turnbull.

Hotel Cecil stationery. London

Dear Bunny:

Of course I’m wild with jealousy! Do you think you can indecently parade this obscene success before my envious desposition, with equanaminity, you are mistaken.

God damn the continent of Europe. It is of merely antiquarian interest. Rome is only a few years behind Tyre + Babylon. The negroid streak creeps northward to defile the nordic race. Already the Italians have the souls of blackamoors. Raise the bars of immigration and permit only Scandinavians, Teutons, Anglo Saxons + Celts to enter. France made me sick. It’s silly pose as the thing the world has to save. I think its a shame that England + America didn’t let Germany conquor Europe. Its the only thing that would have saved the fleet of tottering old wrecks. My reactions were all philistine, anti-socialistic, provincial + racially snobbish. I believe at last in the white man’s burden. We are as far above the modern frenchman as he is above the negro. Even in art! Italy has no one. When Antole France dies French literature will be a silly jealous rehashing of technical quarrels. They’re thru + done. You may have spoken in jest about N.Y. as the capitol of culture but in 25 years it will be just as London is now. Culture follows money + all the refinements of aesthetescism can’t stave off its change of seat (Christ! what a metaphor). We will be the Romans in the next generation as the English are now.

Alec sent me your article. I read it half a dozen times and think it is magnificent. I can’t tell you how I hate you. I don’t hate Don Stuart half as much (tho I find that I am suddenly + curiously irritated by him) because I don’t really dread him. But you! Keep out of my sight. I want no more of your articles!

Enclosed is 2 francs with which you will please find a french slave to make me a typed copy of your letter from Mencken. Send here at once, if it please you. I will destroy it on reading it. Please! I’d do as much for you. I haven’t gotten hold of a Bookman.

Paradise is out here. Of 20 reviews about half are mildly favorable, a quarter of them imply that I’ve read “Sinister Street once too often” + the other five (including the Times) damn it summarily as artificial. I doubt if it sells 1,500 copies.

Menckens 1st series of Predjudices is attracting wide attention here. Wonderful review in the Times.

I’m delighted to hear about The Undertaker. Alec wrote describing how John “goes to see Mrs. Knopf and rubs himself against her passionately hoping for early fall publication.” Edna has no doubt told you how we scoured Paris for you. Idiot! The American Express mail dept has my adress. Why didn’t you register. We came back to Paris especially to see you. Needless to say our idea of a year in Italy was well shattered + we sail for America on the 9th + thence to The “Sahara of Bozart” (Montgomery) for life.

With envious curses + hopes of an immediate responce

F. Scott Fitzgerald (author of Flappers +

Philosophers [juvenile])

Notes:

Wilson’s New Republic article on Mencken, which Mencken had commended.

Alexander McKaig, Princeton ’17.

The Undertaker’s Garland (1922), a collection of verse and prose by Wilson and Bishop.

Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay.

26. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

June 22, 1921

Mont-Thabor Hotel, Paris

Dear Fitz: I find no word from you at the American Express (though I got a postcard in America before I left), so am writing to find out where you arc, etc. I arrived in Paris the day before yesterday and am not yet settled, so please write to me c/o Credit Commercial de France, 22 Boulevard des Capucines. I'm very anxious to see you, when possible. If you are in Italy, I expect to go there sometime in August.

I may say in closing that the two great literary successes of the States since your departure are Don Stewart and myself. The first installment of Don Stewart's History arrived with a crash, Prodigious praise from F.P.A., Broun, Cabell, etc.—and he was finally summoned to the penetralia of The Smart Set and requested to write them an article on Yale. And as for myself, my Mencken article, completely rewritten from the version you saw, enabled me to leave The New Republic in an aurora borealis of glory. It brought me not only a letter from the Prophet himself—from the enthusiasm of which I am still recovering—but also complimentary communications from Van Wyck Brooks and Lawrence Gilman. The Globe wrote an editorial on it; one unknown person sent me an enormously long letter to prove that I was all wrong. I am doing all this boasting on behalf of Dr. Stewart and myself, frankly, to make you jealous. As you know, I have always regarded your great capacity for envy as the one unfortunate blemish in an otherwise consummately admirable character and I hope to cure you, as G. B. Shaw describes intelligent men, in Back to Methuselah, being cured of false ideas, by homeopathic doses of the disease. (This is both idiotic and dull, I'm afraid, but it's very late and I'm exhausted.)

By the way, Mencken summoned me to the sacred chamber of The Smart Set the day you sailed, to talk to me about The Undertaker's Garland, and I greatly astounded Nathan by telling him that you were going abroad. He seemed a little crestfallen and I think he was sorry that you should have got off without patching up your quarrel. He told me that he was going to Europe himself and got your address from me, saying that he was going to look you up.

Scribner's passed The Undertaker up, with kind and noncommittal words. So we think we'll fall back on Knopf in the fall, Let me hear from you.

Yours for the shifting of the world's capital of culture from Paris to New York, E.W.

27. To F. Scott Fitzgerald, From Edmund Wilson

July 5, 1921

16 rue du Four, Paris

Dear Scott: It was terrible that we didn't meet, I never knew you had been here until John Wyeth told me—I think, the day you left. But you should have left a note at the American Express. I called there, expecting something from you.

Your reaction to the Continent is only what most Americans go through when they come over for the first time as late in life as you. It is due, I suppose, first, to the fact that they can't understand the language and, consequently, assume both that there is nothing doing and that there is something inherently hateful about a people who, not being able to make themselves understood, present such a blank facade to a foreigner, and second, to the fact that, having been a part of one civilization all their lives, it is difficult for them to adjust themselves to another, whether superior or inferior, as it is for any other kind of animal to learn to live in a different environment. The lower animals frequently die, when transplanted; Fitzgerald denounces European civilization and returns at once to God's country. The truth is that you are so saturated with twentieth-century America, bad as well as good—you are so used to hotels, plumbing, drugstores, aesthetic ideals, and vast commercial prosperity of the country—that you can't appreciate those institutions of France, for example, which are really superior to American ones. If you had only given it a chance to sink in! I wish that I could have seen you and tried to induct you a little into the amenities of France. Paris seems to me an ideal place to live: it combines all the attractions and conveniences of a large city with all the freedom, beauty, and regard for the arts and pleasures of a place like Princeton. I find myself more contented and at ease here than anywhere else I know. Take my advice, cancel your passage and come to Paris for the summer! Settle down and learn French and apply a little French leisure and measure to that restless and jumpy nervous system. It would be a service to American letters: your novels would never be the same afterwards. That's one reason I came to France, by the way: in America I feel so superior and culturally sophisticated in comparison to the rest of the intellectual and artistic life of the country that I am in danger of regarding my present attainments as an absolute standard and am obliged to save my soul by emigrating into a country which humiliates me intellectually and artistically by surrounding me with a solid perfection of a standard arrived at by way of Racine, Moliere, La Bruyere, Pascal, Voltaire, Vigny, Renan, Taine, Flaubert, Maupassant, and Anatole France. I don't mean to say, of course, that I can actually do better work than anybody else in America; I simply mean that I feel as if I had higher critical standards and that, since in America all standards are let down, I am afraid mine will drop, too; it is too easy to be a highbrow or an artist in America these days; every American savant and artist should beware of falling a victim to the ease with which a traditionless and half-educated public (I mean the growing public for really good stuff) can be impressed, delighted, and satisfied; the Messrs. Mencken, Nathan, Cabell, Dreiser, Anderson, Lewis, Dell, Lippmann, Rosenfeld, Fitzgerald, etc., etc., should all beware of this; let them remember that, like John Stuart Mill, they all owe a good deal of their eminence “to the flatness of the surrounding country”! I do think seriously that there is a great hope for New York as a cultural center; it seems to me that there is a lot doing intellectually in America just now—America seems to be actually beginning to express herself in something like an idiom of her own. But, believe me, she has a long way to go. The commercialism and industrialism, with no older and more civilized civilization behind except one layer of eighteenth-century civilization on the East Coast, impose a terrific handicap upon any other sort of endeavor: the intellectual and aesthetic manifestations have to crowd their way up and out from between the crevices left by the factories, the office buildings, the apartment houses, and the banks; the country was simply not built for them and, if they escape with their lives, they can thank God, but would better not think they are too percent elect, attired in authentic and untarnished vestments of light, because they have obviously been stunted and deformed at birth and afterwards greatly battered and contaminated in their struggle to get out. Cabell seems to me a great instance of this: it is not the fact that he is a first-rate writer (I don't think, on the whole, that he is) which has won him the first place in public (enlightened public) estimation; it is the fact that he makes serious artistic pretensions and has labored long and conscientiously (and not altogether without success) to make them good. We haven't any Anatole France, or any of the classic literature which made Anatole France possible; consequently, Cabell looks good to us.

When I began this letter I intended to write only a page, but your strictures upon poor old France demanded a complete explanation of practically everything from the beginning of the world. I don't hope to persuade you to stay in Europe and I suppose you haven't time to come back to France. It's a great pity. (Have you ever tried the Paris-London airline, by the way? I think I shall, if I go to England.)

Mencken's letter went somewhat as follows (I haven't it with me):

“Dear Mr. Wilson: It would be needless to thank you. No one has ever done me before on so lavish a scale, or with so persuasive an eloquence. A little more and you would have persuaded even me. But what engages me more particularly as a practical critic is the critical penetration of the second half of your article. Here, I think, you have told the truth. The beer cellar, these days, has become as impossible as the ivory tower. One is irresistibly impelled to rush out and crack a head or two—that is, to do something or other for the sake of common decency. God knows what can be done. But, at any rate, it is easier to do with such a fellow as you in the grandstand.

“You must come down to Baltimore sometime. I pledge you in a large Humpen of malt. Yours sincerely, H. L. Mencken.”

I am sending you The Bookman: I happen to have a copy.

Yours always,

E.W.

28. [Fragment] To John Peale Bishop, From Edmund Wilson

July 3, 1921

Paris

… The Fltzgeralds have recently been here and tried to get hold of me, but, to my infinite regret, couldn't. I didn't know about it until after they had gone back to London. It seems they hate Europe and are planning to go back to America almost immediately. The story is that they were put out of a hotel because Zelda insisted upon tying the elevator—one of those little half-ass affairs that you run yourself—to the floor where she was living so that she would be sure to have it on hand when she had finished dressing for dinner…

29. [Fragment] To Stanley Dell, From Edmund Wilson

August 16, 1921

Haslemere, Surrey, England

… The Fitzgeralds, as you perhaps know, came to Europe last May on the $7,000 which Fitz got for his new novel from The Metropolitan, The astonishing (though, I suppose, natural) thing was that they hated Europe, especially the Continent, and started back home after staying not much more than a month. They had apparently become so accustomed to the luxurious appointment of the Ritz and the Plaza and the jazz of American life that Europe seemed to them too tame and too primitive to he taken seriously. I had a violent letter from Fitz in which he declared that the modern American was as far superior to the modern Frenchman as the modern Frenchman was superior to the Negro …

30. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

Postmarked November 25, 1921

ALS, 5pp. Yale University; From Turnbull, Life In Letters.

626 Goodrich Ave.

St. Paul, Minn.

Dear Bunny—

Thank you for your congratulations. * I’m glad the damn thing’s over. Zelda came through without a scratch + I have awarded her the croix-deguerre with palm. Speaking of France, the great general with the suggestive name is in town today.

I agree with you about Mencken—Weaver + Dell are both something awful. I like some of John’s critisism but Christ! he is utterly dishonest. Why does he tell us how rotten he thinks Mooncalf is and then give it a “polite bow” in his column. Likewise he told me personally that my “book just missed being a great book” + how I was the most hopeful ect ect + then damned me with faint praise in two papers six months before I’m published. I am sat with a condescending bow “halfway between the posts of Compton Mckenzie and Booth Tarkington.” So much for that!

I have almost completely rewritten my book. ** Do you remember you told me that in my midnight symposium scene I had sort of set the stage for a play that never came off—in other words when they all began to talk none of them had anything important to say. I’ve interpolated some recent ideas of my own and (possibly) of others. See enclosure at end of letter. ***

Having desposed of myself I turn to you. I am glad you + Ted Paramore are together. I was never crazy over the oboist nor the accepter of invitations and I imagine they must have been small consolation to live with. I like Ted immensely. He is a little too much the successful Eli to live comfortably in his mind’s bed-chamber but I like him immensely.

What in hell does this mean? My controll must have dictated it. His name is Mr. Ikki and he is an Alaskan orange-grower.

Nathan and me have become reconciled by letter. If the baby is ugly she can retire into the shelter of her full name Frances Scott.

I hear strange stories about you and your private life. Are they all true? What are you going to do? Free lance? I’m delighted about the undertaker’s garland. Why not have a preface by that famous undertaker in New York. Say justa blurb on the cover. He might do it if he had a sense of humor

St. Paul is dull as hell. Have written two good short stories + three cheap ones.

I liked Three Soldiers immensely + reviewed it for the St. Paul Daily News. I am tired of modern novels + have just finished Paine’s biography of Clemens. It’s excellent. Do let me see if if you do me for the Bookman. Isn’t The Triumph of the Egg a wonderful title. I liked both John’s + Don’s articles in Smart Set. I am lonesome for N.Y. May get there next fall + may go to England to live. Yours in this hell-hole of life & time,

the world.

F Scott Fitz—

Notes:

* On the birth of the Fitzgeralds’ daughter, Scottie.

** The Beautiful and Damned.

*** These enclosures included the greater part of Maury Noble's monologue in the chapter called “Symposium.”

John V. A. Weaver, poet and reviewer; Floyd Dell, novelist best known for Moon-Calf (1920).

E. E. Paramore, friend of Wilson, and, later, Fitzgerald’s collaborator on Three Comrades.

George Jean Nathan, co-editor with Mencken of The Smart Set; he was the model for Maury Noble in The Beautiful and Damned.

1921 novel by John Dos Passos.

Mark Twain: A Biography, 3 vols. (1912), by Albert Bigelow Paine.

1921 story collection by Sherwood Anderson.

Bishop and Stewart.

31. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

626 Goodrich Avenue St. Paul, Minnesota

[Postmarked January 24, 1922]

From Turnbull.

Dear Bunny:

Farrar tells a man here that I'm to be in the March “Literary Spotlight.” 1 I deduce that this is your doing. My curiosity is at fever heat—for God's sake send me a copy immediately.

Have you read Upton Sinclair's The Brass Check?

Have you seen Hergesheimer's movie Tol'able David?

Both are excellent. I have written two wonderful stories and get letters of praise from six editors with the addenda that “our readers, however, would be offended.” Very discouraging. Also discouraging that Knopf has put off the Garland till fall. I enjoyed your da-daist article in Vanity Fair—also the free advertising Bishop gave us. Zelda says the picture of you is “beautiful and bloodless.”

I am bored as hell out here. The baby is well—we dazzle her exquisite eyes with gold pieces in the hopes that she'll marry a millionaire. We'll be East for ten days early in March.

I have heard vague and unfathomable stories about your private life —not that you have become a pervert or anything—romantic stories. I wish to God you were not so reticent!

What are you doing? I was tremendously interested by all the data in your last letter. I am dying of a sort of emotional anemia like the lady in Pound's poem. The Briary Bush is stinko. Cytherea is Hergesheimer's best but it's not quite.

Yours, John Grier Hibben 2

Notes:

1A series of portraits of contemporary writers published in The Bookman.

2 John Grier Hibben, then president of Princeton.

32. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

January 1922

ALS, 7 pp. Yale University; From Turnbull, Life In Letters.

626 Goodrich Ave.

St. Paul, Minn

Dear Bunny—

Needless to say I have never read anything with quite the uncanny fascination with which I read your article.1 It is, of course, the only intelligible and intelligent thing of any length which has been written about me and my stuff—and like everything you write it seems to me pretty generally true. I am guilty of its every stricture and I take an extraordinary delight in its considered approbation. I don't see how I could possibly be offended at anything in it—on the contrary it pleases me more to be compared to “standards out of time,” than to merely the usual scapegoats of contemporary criticism. Of course I'm going to carp at it a little but merely to conform to convention. I like it, I think it's an unprejudiced diagnosis and I am considerably in your debt for the interest which impelled you to write it.

Now as to the liquor thing—it's true, but nevertheless I'm going to ask you take it out. It leaves a loophole through which I can be attacked and discredited by every moralist who reads the article. Wasn't it Bernard Shaw who said that you've either got to be conventional in your work or in your private life or get into trouble? Anyway the legend about my liquoring is terribly widespread and this thing would hurt me more than you could imagine—both in my contact with the people with whom I'm thrown—relatives and respectable friends— and, what is much more important, financially.

So I'm asking you to cut.

1. “when sober” on page one. I have indicated it. If you want to substitute “when not unduly celebrating” or some innuendo no more definite than that, all right.

2. From “This quotation indicates …” to “… sets down the facts” would be awfully bad for me. I'd much rather have you cut it or at least leave out the personal implication if you must indicate that my characters drink. As a matter of fact I have never written a line of any kind while I was under the glow of so much as a single cocktail and tho my parties have been many it's been their spectacularity rather than their frequency which has built up the usual “dope-fiend” story. Judge and Mrs. Sayre would be crazy! And they never miss The Bookman.

Now your three influences, St. Paul, Irish (incidentally, though it doesn't matter, I'm not Irish on Father's side—that's where Francis Scott Key comes in) and liquor are all important I grant. But I feel less hesitancy asking you to remove the liquor because your catalogue is not complete anyhow—the most enormous influence on me in the four and a half years since I met her has been the complete, fine and full-hearted selfishness and chill-mindedness of Zelda.

Both Zelda and I roared over the Anthony-Maury incident. You've improved mine (which was to have Muriel go blind) by 100%—we were utterly convulsed.

But Bunny, and this I hate to ask you, please take out the soldier incident. I am afraid of it. It will not only utterly spoil the effect of the incident in the book but will give rise to the most unpleasant series of events imaginable. Ever since Three Soldiers, The New York Times has been itching for a chance to get at the critics of the war. If they got hold of this I would be assailed with the most violent vituperation in the press of the entire country (and you know what the press can do, how they can present an incident to make a man upholding an unpopular cause into the likeness of a monster—vide Upton Sinclair). And, by God, they would! Besides the incident is not correct. I didn't apologize. I told the Colonel about it very proudly. I wasn't sorry for months afterwards and then it was only a novelist's remorse.

So for God's sake cut that paragraph. I'd be wild if it appeared! And it would without doubt do me serious harm.

I note from the quotation from “Head and Shoulders” and from reference to “Bernice” that you have plowed through Flappers for which conscientious labor I thank you. When the strain has abated I will send you two exquisite stories in what Professor Lemuel Ozuk in his definitive biography will call my “second” or “neo-flapper” manner.

But one more carp before I close. Gloria and Anthony are representative. They are two of the great army of the rootless who float around New York. There must be thousands. Still, I didn't bring it out.

With these two cuts, Bunny, the article ought to be in my favor. At any rate I enjoyed it enormously and shall try to reciprocate in some way on The Undertaker's Garland though I doubt whether you'd trust it to my palsied hands for review. Don't change the Irish thing—it's much better as it is—besides the quotation hints at the whiskey motif.

Forever,

Benjamin Disraeli

I am consoled for asking you to cut the soldier and alcoholic paragraphs by the fact that if you hadn't known me you couldn't or wouldn't have put them in. They have a critical value but are really personal gossip.

I'm glad about the novelette in Smart Set. I am about to send them one. I am writing a comedy—or a burlesque or something. The “romantic stories” about you are none of my business. They will keep until I see you.

Hersesassery—Quelque mot!

How do you like echolalia for “meaningless chatter?”

Glad you like the title motto— Zelda sends best— Remember me to Ted.1 Did he say I was “old woman with jewel?”

Notes:

1 This letter and the letter after it refer to Wilson's essay, “F. Scott Fitzgerald,” in the March, 1922, Bookman (reprinted in Wilson's collection, The Shores of Light).

1 Ted Paramore. Actually it was Edna Millay who had said that to meet Fitzgerald was to think of a stupid old woman with whom someone had left a diamond (his talent), and Wilson had quoted the remark at the beginning of his Bookman essay.

Wilson’s “F. Scott Fitzgerald,” The Bookman (March 1922).

Wilson’s burlesque of the final meeting of Anthony Patch and Maury Noble reads: “It seemed to Anthony that Maury’s eyes had a fixed glassy stare; his legs moved stiffly as he walked and when he spoke his voice had no life in it. When Anthony came nearer, he saw that Maury was dead!”

Unidentified incident during Fitzgerald’s army service.

Sinclair, whose novels and nonfiction books treated controversial subjects, was frequently attacked in the press.

Edna St. Vincent Millay had compared Fitzgerald to a stupid old woman with whom someone had left a diamond.

33. To Edmund Wilson, From Fitzgerald

ALS, 2 pp. Yale University; From Turnbull, Life In Letters.

626 Goodrich Ave, St. Paul, Minn

Feb 6th 1921 [1922]

Dear Bunny—