Dear Scott/Dear Max

Correspondence of Scott Fitzgerald and Maxwell Perkins

Chapter 4: The Count of Darkness (March 1935 - December 1940)

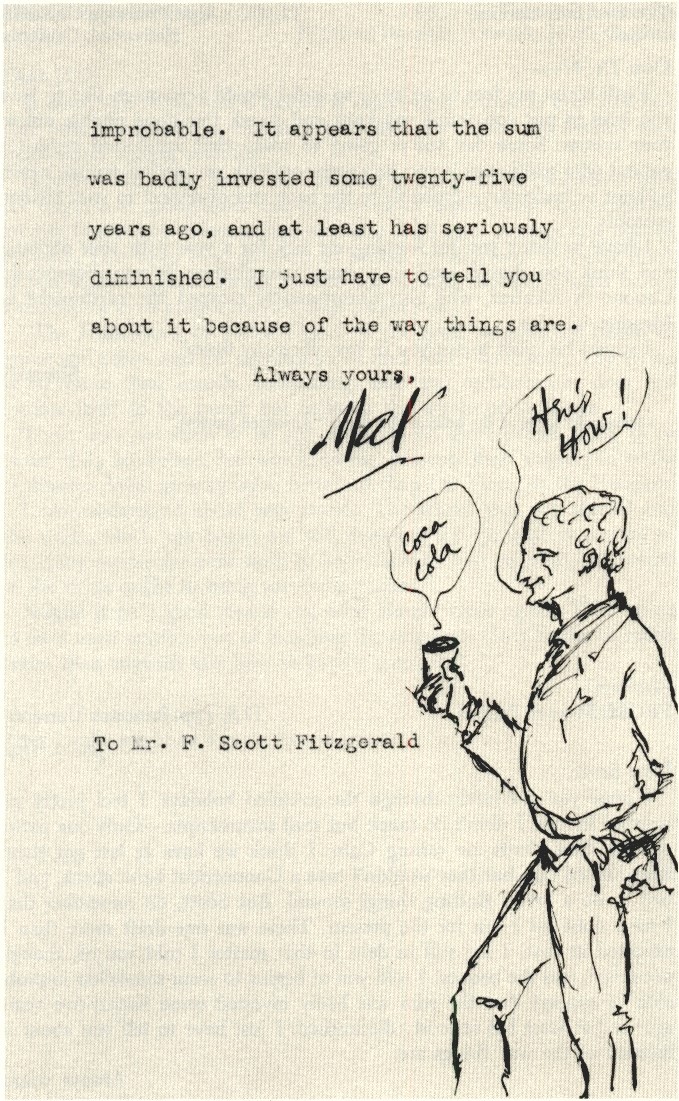

311. TO: Maxwell Perkins

TL, 2 pp. Princeton University Baltimore, Maryland

Dear Max: You might file this

F Scott Fitzgerald1

March 26, 1935.

To Maxwell Perkins

This collection will be published only in case of my sudden death. It contains many stories that have been chosen for anthologies but, though it is the winnowing from almost fifty stories, none that I have seen fit to reprint in book form. This is in some measure because the best of these stories have been stripped of their high spots which were woven into novels—but it is also because each story contains some special fault— sentimentality, faulty construction, confusing change of pace—or else was too obviously made for the trade.

But readers of my other books will find whole passages here and there which I have used elsewhere—so I should prefer that this collection should be allowed to run what course it may have, and die with its season.

If the Mediaeval stories are six or more they should be in a small book of their own. If less than six they should be in one section in this book. Note date above—there may be other good ones after this date.

CHOOSE FROM THESE |

THESE ARE SCRAPPED |

||

|

|

1919 |

Myra Meets His Family |

|

|

|

The Smilers |

1921 |

Two for a Cent |

1921 |

The Popular Girl |

|

|

1923 |

Dice Brass Knuckles and Guitar |

1924 |

One of My Oldest Friends |

1924 |

John Jackson's Arcady |

|

The Pusher in the Face |

|

The Unspeakable Egg |

|

|

|

The Third Casket |

|

|

|

Love in the Night |

1925 |

Presumption |

1925 |

Not in the Guide Book |

|

Adolescent Marriage |

|

A Penny Spent |

1926 |

The Dance |

1926 |

Your Way and Mine |

1927 |

Jacob's Ladder |

1927 |

The Love Boat |

|

The Bowl |

|

Magnetism |

|

Outside the Cabinet Makers |

|

|

|

|

1928 |

A Night at the Fair |

1929 |

The Rough Crossing |

1929 |

Forging Ahead |

|

At Your Age |

|

Basil and Cleopatra |

|

|

|

The Swimmers |

1930 |

One Trip Abroad |

1930 |

The Bridal Party |

|

The Hotel Child |

|

A Snobbish Story |

1931 |

A New Leaf |

1931 |

Indecision |

|

Emotional Bankruptcy |

|

Flight and Pursuit |

|

Between Three and Four |

|

Half a Dozen of the Others |

|

A Change of Class |

|

Diagnosis |

|

A Freeze Out |

|

|

|

|

1932 |

What a Handsome Pair |

|

|

|

The Rubber Check |

|

|

|

On Schedule |

1933 |

More than Just a House |

|

|

|

I Got Shoes |

|

|

|

The Family Bus |

|

|

1934 |

No Flowers |

1934 |

New Types |

|

Her Last Case |

|

|

1935 |

The Intimate Strangers |

1935 |

Shaggy's Morning |

|

And, to date four mediaval stories |

|

|

Notes:

1 Added in holograph.

312. To Fitzgerald

April 8, 1935

Dear Scott:

I sent Hem a copy of “Taps at Reveille”,* but not in time for him to read it before he started on a trip for Bimini with Dos+ and Make [Mike] Strater. But I just had a letter from him in which he says: “How is Scott? I wish I could see him. A strange thing is that in retrospect his Tender is the Night gets better and better. I wish you would tell him I said so.”

Always yours,

Notes:

* Published late in March.

+ John Dos Passos.

313. To Perkins

1307 Park Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland,

April 15, 1935.

Dear Max:

You don't say anything about “Taps” so I gather it hasn't caught on at all. I hope at least it will pay for itself and its corrections. There was a swell review in The Nation;** did you see it?

I went away for another week but history didn't repeat itself and the trip was rather a waste. Thanks for the message from Ernest. I'd like to see him too and I always think of my friendship with him as being one of the high spots of life. But I still believe that such things have a mortality, perhaps in reaction to their very excessive life, and that we will never again see very much of each other. I appreciate what he said about “Tender is the Night.” Things happen all the time which make me think that it is not destined to die quite as easily as the boys-in-a-hurry prophesied. However, I made many mistakes about it from its delay onward, the biggest of which was to refuse the Literary Guild subsidy.

Haven't seen Beth since I got back and am calling her up today to see if she's here. I am waiting eagerly for a first installment of Ernest's book.* When are you coming south? Zelda, after a terrible crisis, is somewhat better. I am, of course, on the wagon as always, but life moves at an uninspiring gait and there is less progress than I could wish on the Mediaeval series—all in all an annoying situation as these should be my most productive years. I've simply got to arrange something for this summer that will bring me to life again, but what it should be is by no means apparent.

About 1929 I wrote a story called “Outside the Cabinet-Maker's,” which ran in the Century Magazine. I either lost it here or else sent it to you with the first batch of selected stories for Taps and it was not returned. Will you (a) see if you've got it? or (b) tell me what and where the Century Company is now and whom I should address to get a copy of the magazine?

I've had a swell portrait painted at practically no charge and next time I come to New York I am going to spend a morning tearing out of your files all those preposterous masks with which you have been libeling me for the last decade.

Just found another whole paragraph in Taps, top of page 384, which appears in Tender Is the Night. I'd carefully elided it and written the paragraph beneath it to replace it, but the proofreaders slipped and put them both in.

Ever yours,

Notes:

** By William Troy (April 17, 1935).

* The Green Hills of Africa, which ran serially, in seven installments, in Scribner's Magazine (prior to its book publication), beginning in May 1935.

Also Turnbull.

314. To Perkins

1307 Park Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland,

April 17, 1935.

Dear Max:

Reading Tom Wolfe's story^ in the current Mondern Monthly makes me wish he was the sort of person you could talk to about his stuff. It has all his faults and virtues. It seems to me that with any sense of humor he could see the Dreiserian absurdities of how the circus people “ate the cod, bass, mackerel, halibut, clams and oysters of the New England coast, the terrapin of Maryland, the fat beeves, porks and cereals of the middle west” etc. etc. down to “the pink meated lobsters that grope their way along the sea-floors of America.” And then (after one of his fine paragraphs which sounds a note to be expanded later) he remarks that they leave nothing behind except “the droppings of the camel and the elephant in Illinois.” A few pages further on his redundance ruined some paragraphs (see the last complete paragraph on page 103) that might have been gorgeous. I sympathize with his use of repetition, of Joyce-like words, endless metaphor, but I wish he could have seen the disgust in Edmund Wilson's face when I once tried to interpolate part of a rhymed sonnet in the middle of a novel, disguised as prose. How he can put side by side such a mess as “With chitterling tricker fast-fluttering skirrs of sound the palmy honied birderies came” and such fine phrases as “tongue-trilling chirrs, plum-bellied smoothness, sweet lucidity” I don't know. He who has such infinite power of suggestion and delicacy has absolutely no right to glut people on whole meals of caviar. I hope to Christ he isn't taking all these emasculated paeans to his vitality seriously. I'd hate to see such an exquisite talent turn into one of those muscle-bound and useless giants seen in a circus. Athletes have got to learn their games; they shouldn't just be content to tense their muscles, and if they do they suddenly find when called upon to bring off a necessary effect they are simply liable to hurl the shot into the crowd and not break any records at all. The metaphor is mixed but I think you will understand what I mean, and that he would too—save for his tendency to almost feminine horror if he thinks anyone is going to lay hands on his precious talent. I think his lack of humility is his most difficult characteristic, a lack oddly enough which I associate only with second or third rate writers. He was badly taught by bad teachers and now he hates learning.

There is another side of him that I find myself doubting, but this is something that no one could ever teach or tell him. His lack of feeling other people's passions, the lyrical value of Eugene Gant's love affair with the universe—is that going to last through a whole saga? God, I wish he could discipline himself and really plan a novel.

I wrote you the other day and the only other point of this letter is that I've now made a careful plan of the Mediaeval novel as a whole (tentatively called “Philippe, Count of Darkness” confidential) including the planning of the parts which I can sell and the parts which I can't. I think you could publish it either late in the spring of '36 or early in the fall of the same year. This depends entirely on how the money question goes this year. It will run to about 90,000 words and will be a novel in every sense with the episodes unrecognizable as such. That is my only plan. I wish I had these great masses of manuscripts stored away like Wolfe and Hemingway but this goose is beginning to be pretty thoroughly plucked I am afraid.

A young man has dramatized “Tender is the Night” and I am hoping something may come of it. I may be in New York for a day and a night within the next fortnight.

Ever yours,

Later—Went to N.Y. as you know, but one day only. Didn't think I would like Cape that day.* Sorry you & Nora Flynn^ didn't meet. No news here—I think Beth is leaving soon.

Notes:

^ “Circus at Dawn.”

* Perkins was having lunch with Jonathan Cape, the English publisher, and had asked Fitzgerald to join them.

^ Nora Langhorne Flynn, who, with her husband, Lefty, befriended Fitzgerald during 1935 and 1936.

Also Turnbull.

315. To Fitzgerald

April 25, 1935

Dear Scott:

I was just having lunch with Jim Boyd, who, by the way, will be in Baltimore tomorrow. I happened to tell him that you were doing that mediaeval series (but I did not mention the title of the novel, and won't) which was especially in my mind since I had just read your letter. Jim was simply delighted. He has the greatest admiration for your talents, and he said that he had not known about this, but that he himself had thought that the best thing you could do for the moment was a historical novel. I told you that Ned Sheldon** had said the same thing. It is curious they both should have thought of it,—and both of them think that no one surpasses you in possibilities.

It would be a grand thing if some time it should come about that you could talk to Tom. Of course everything you say is true as truth can be. But even if one had an utterly free hand, instead of being subject to constant abuse (God damned Harvard English, grovelling at the feet of Henry James, etc.) it would be a matter of editing inside sentences even, and that would be a dangerous business. But gradually criticism, and age too, may make an impression. By the way.—That Calverton story to the effect that Tom thought he was better than so and so, and so and so, while true in a literal sense, was not true in spirit. I think it is right enough Tom should feel the way he does, which is that what he has to say is so overwhelmingly important that it is all he can see. It is not that he thinks he is better than anyone else. He just does not think about the other people at all. When he reads them he is quite keen about them for a while, but it does not seem to him to be the important thing that they are doing because what he is doing seems to him momentous.

I swear I do not see why a good man could not make a grand play out of “Tender Is the Night”.

Always yours,

Notes:

** Probably American dramatist Edward Sheldon.

316. To Perkins

1307 Park Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland,

April 29, 1935.

Dear Max:

Jim Boyd called me up on race-day76 but I missed him as he pulled out of the Belvedere before the race was over. Elizabeth, by the way, left yesterday or today.

I got “Roll River”* and in the same mail another book called “Deep Dark River,” + (Farrar & Rhinehart), so Max, if you don't mind I want the names of my books changed to fit in with this new mode. They should be called “This Side of the River,” “Rivers and Philosophers,” “Tender is the River,” and “Rivers at Reveille.” Please see to this immediately because dat ol' debbil certainly does make sales.

Zelda is better. I am thinking of closing up shop here and going to North Carolina for a real physical rest as I am God damned tired of being half sick and half well. I will be writing all the time of course.

I would rather you didn't mention the century of my novel or advise people that some of it is in the Red Book. Let it just stand for the present as an historical novel.

Ever yours,

Notes:

* A novel by James Boyd, published by Scribners in 1935.

+ A novel by Robert Rylee.

76. Probably the day of the Preakness Stakes, an annual horserace run at Pimlico Race Track in Baltimore.

317. To Perkins

1307 Park Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland,

May 11, 1935.

Dear Max:

It was fine seeing you but I was in a scrappy mood about Tom Wolfe. I simply cannot see the sign of achievement there yet, but I see that you are very close to the book and you don't particularly relish such an attitude. I am closing the house and going away somewhere for a couple of months and will send you an address when I get one.

I'd like to see Ernest but it seems a long way and I would not like to see him except under the most favorable of circumstances because I don't think I am the pleasantest company of late.** Zelda is in very bad condition and my own mood always somehow reflects it.

Katy Dos Passos was here and in her version the bullet bounced off the side of the boat, but I suppose when Ernest's legend approaches the Bunyan type it will have bounced off the moon, so it is much the same thing.

Had a nice letter from Jim Boyd agreeing with me about Clara but not about the weak writing at the end. I am quite likely to see him this summer.

Ever yours,

Notes:

** Perkins, on May 6th, had written that Hemingway, who was recovering from a bullet wound in his leg, had invited Fitzgerald to visit him in Bimini.

Also Turnbull.

318. To Perkins

Hotel Stafford, Baltimore, Md. Sunday evening

[ca. June 25, 1935]

Dear Max:

I feel I owe you a word of explanation; 1st: As to the health business, I was given what amounted to a death sentence about 3 months ago. It was just before I last saw you—which was why, I think, I got into that silly quarrel with you about Tom Wolfe that I've regretted ever since. I was a good deal dismayed & probably jealous, so forget all I said that night. You know I've always thought there was plenty room in America for more than one good writer, & you'll admit it wasn't like me.

Anyhow what upset me most was that it came just two months after the liquor question was in hand at last—and I was quite reconciled, simply cross and upset at the arbitrary change of plan. (I never felt emotional about it until a fortnight ago when I learned that the Great Scene wasn't coming off. It seemed such a shame after such good rehearsals that one grew suddenly sentimental and sorry for oneself.)

2nd Came up to Baltimore for five days* to see Zelda who seems hopeless & send Scotty to camp, I had 24 hrs with nothing to do and went to N.Y. to see a woman I'm very fond of—its a long peculiar story (…—one of the curious series of relationships that run thru a man's life). Anyhow she'd given up the wk. end at the last minute to meet me & it was impossible to leave her to see you.

Putting Scotty on train in 10 minutes.

In haste, always yrs.

I wish Struthers Burt would decide on a name—I call him everything but Katherine! ^

Notes:

* Fitzgerald had been spending the summer at the Grove Park Inn, in Asheville, North Carolina.

^ Burt's full name was Maxwell Struthers Burt. His wife's name was Katherine.

Also Turnbull.

319. To Fitzgerald

Sept. 28, 1935

Dear Scott:

I have got to go for a two weeks' vacation beginning Tuesday, but I expect to come to Baltimore sometime after that.

Ernest is here now, in fine shape. He is going to be in this region probably for some time because he wants to wait until it gets cool enough to return to Key West. He means to go somewhere in the country. He has speculated several times about seeing you, but he is bent upon writing stories,—has done a couple.

Every writer seems to have to go through a period when the tide runs against him strongly, and at the worst it is better that it should have done this when Ernest was writing books that are in a general sense minor ones. That is, the kind that the trade and the run of the public are bound to regard that way. I hope we can think of something to be done about it between now and October 25th.

I am sorry we did not get Scotty, but Harold did not seem to want to let her go at the beginning, and then Nance had to have her tonsils out.77 The whole family is back from Europe, and we are all in New York.

Yours always,

Notes:

77. Fitzgerald's daughter had been staying with the Obers and plans to have her spend some time with the Perkins family were cancelled when Nancy, the youngest Perkins daughter, became ill.

320. To Perkins

Cambridge Arms, Baltimore, Maryland,

October 24, 1935.

Dear Max:

Thank you again.* I haven't realized on either of the two stories but will hear from one this week end and from the other the beginning of next week.

Have you got any suggestions about the Red Book series? I now have about 30,000 words (in the 4 written stories) but Balmer of the Red Book is noncommittal about whether he wants any more or not. What could Scribner's pay in cash for the rest of the series? Or have you read the last two and did you like them? The fourth isn't published yet. I know this is a wild idea and even granted that the material fitted Scribner's you wouldn't have the advantage of featuring it as a serial from the beginning, but of course it is to your advantage to have me finish the book.

The original plan was to have been a book of over 100,000 words, but supposing instead, I published two books of 60,000 words each about my noble Philippe, the first book dealing with his youth. That book you see would be half done now.

This all sounds like a make-shift arrangement but I can't see how in the next six months I can raise enough money to continue the mediaeval theme unless it is somehow subsidized by serialization. Have you any ideas?

Ever yours,

Notes:

* Perkins had deposited $300 in Fitzgerald's Baltimore bank on October 18th.

321. To Fitzgerald

Oct. 26, 1935

Dear Scott:

It seems to me most unlikely that we could do anything through the magazine about stories you began with the Red Book, but if you have copies of those that have been published, I wish I could read them. I only read the first one. Anyhow, by doing that, I could have more idea of the advisability of breaking the scheme into two books. It might be a good thing to do.

Ernest got a first-rate review* in the Sunday Times Supplement, a very good review in the Tribune Supplement, excellent short reviews in the Atlantic and in Time, a bad review in the Saturday Review (which does not count for much) and mostly unfavorable comment from Gannett,^ and very unfavorable from Chamberlain,** but the review in the Times is more important than all the others put together, generally speaking. The unfavorable reviews are mostly colored by this prevalent idea that you ought to be writing only about the troubles of the day, and are disapproving of anything so remote from present social problems as a hunting expedition.

I had lunch with Bunny Wilson, who seems better and happier than in years, and very enthusiastic about Russia as a country, and a people. I got the impression that his views on Communism were somewhat sobered and more philosophical, and that he thought better of his own country. I suspect he now feels that whatever form of society Russians and Americans are revolving toward is a long slow process. He also told me that he had inherited from an uncle enough money to make his situation considerably more comfortable.

Always yours,

Notes:

*Of The Green Hills of Africa.

^ Critic Lewis Gannett, whose book reviews appeared daily in the New York Herald Tribune.

** Critic John Chamberlain, whose book reviews appeared in the daily New York Times.

322. To Perkins

1 East 34th Street, Baltimore, Maryland,

March 17, 1936.

Dear Max:

A kid named Vincent McHugh has written me asking me to recommend him to you. Ordinarily I would not do such things any more but he has been a sort of unknown protege of mine for some time. He has published a book called Sing Before Breakfast which I thought was a remarkable book and showed a very definite temperament. I'm not promising you that he is as strong a personality as Ernest or Caldwell or Cantwell or the men that I have previously recommended, but I do wish you would get hold of this earlier book Sing Before Breakfast published by Simon and Schuster in 1933 and consider that as much as what he has to offer at the moment in making your decision.

I know, that due to your experience with Tom Boyd, you place a great deal of emphasis on vitality, but remember that a great deal of the work in this world has been done by sick men and people who at first sight seem to have no vitality will suddenly exhibit great streaks of it. I've never seen this young man but potentially he seems capable of great efforts.78

Things are standing still here. I am waiting to hear this afternoon about a Saturday Evening Post story, which, if it is successful, will continue a series.

Best wishes always,

Notes:

78. Perkins replied, on March 20th, that he had “always been interested” in McHugh ever since Scribners had “most reluctantly” declined Sing Before Breakfast “about which I was very enthusiastic.” He assured Fitzgerald that he would help McHugh in any way he could and that he would read anything McHugh wrote “with great interest.”

Also Turnbull.

323. To Perkins

1 East 34th Street, Baltimore, Maryland,

March 25, 1936.

Dear Max:

In regard to the enclosed letter from Simon and Schuster* do you remember my proposing some years ago to gather up such of my non-fiction as is definitely autobiographical—“How to Live on $36,000 a Year,” etc., “My Relations with Ring Lardner,” a Post article called “A Hundred False Starts,” of hotels stayed at that I did with Zelda and about a half dozen others and making them into a book? At the time you didn't like the idea and I'm quite aware that there's not a penny in it unless it was somehow joined together and given the kind of lift that Gertrude Stein's autobiography^ had. Some of it will be inevitably dated, but there is so much of it and the interest in this Esquire series has been so big that I thought you might reconsider the subject on the chance that there might be money in it. If you don't like the idea what would you think of letting Simon and Schuster try it?

I don't want to spend any time at all on it until I am absolutely sure of publication and, as you know, of course I would prefer to keep identified with the house of Scribner, but in view of the success of the Gertrude Stein book and the Seabrook* book it just might be done with profit.

Ever yours,

Notes:

* Simon and Schuster had written Fitzgerald expressing interest in publishing in book form the autobiographical articles which he was publishing in Esquire.

^ The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

* Probably Asylum by William B. Seabrook (1934), in which the author recounted his experiences in a mental hospital for alcoholics.

324. To Fitzgerald

March 26, 1936

Dear Scott:

I remember your speaking to me about a collection of non-fiction. I did not think well of it as a collection. But do you remember at the time when you were struggling desperately with “Tender Is the Night” and it seemed as if you might not get through with it for long, that I suggested a reminiscent book? It might even have been before you published “Echoes of the Jazz Age” in 1931, which was a beautiful article. I have been reading that again lately, and have been hesitating on the question of asking you to do a reminiscent book,—not autobiographical, but reminiscent. Gertrude Stein's autobiography is an apt one to mention in connection with the idea. I even talked to Gilbert Seldes about it, and he was favorable. I do not think the Esquire pieces ought to be published alone. But as for an autobiographical book which would comprehend what is in them, I would be very much for it. Couldn't you make a really well integrated book? You write non-fiction wonderfully well, your observations are brilliant and acute, and your presentations of real characters like Ring, most admirable. I always wanted you to do such a book as that. Whatever you decide, we want to do, but it would be so much better to make a book out of the materials than merely to take the articles and trim them, and join them up, etc.

Always yours,

325. To Perkins

1 East 34th Street, Baltimore, Maryland,

April 2, 1936.

Dear Max:

Your letter really begs the question because it would be one thing to join those articles together and another to write a book. The list would include the following:

1. A short autobiography I wrote for the Saturday Evening Post “Who's Who and How.”

2. An article on Princeton for College Humor.*

3. An article on being twenty-five for the American. +

4. “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” for the Post.

5. “How to Live on Practically Nothing a Year” for the Post.

6. “Imagination and a Few Mothers” for the Ladies Home Journal.

7. “Wait Till You Have Children of Your Own” for the Woman's Home Companion.

8. “How to Waste Material” for Bookman.

9. “One Hundred False Starts” for Post.

10. “Ring Lardner” New Republic.

11. A short autobiography for New Yorker.**

12. “Girls Believe in Girls” Liberty.

13. “My Lost City” Cosmopolitan (still unpublished, but very good I think.)

14. “Show Mr. and Mrs. F—to—” Esquire.

15. Echoes from [of] the Jazz Age.

16. The three articles about cracking up from Esquire.++

This would total 60,000 words. I would expect to revise it and add certain links, perhaps in some sort of telegraphic flashes between each article.

Whether the book would have the cohesion to sell or not I don't know. It makes a difference whether people think they are getting some real inside stuff or whether they think a collection is thrown together. As it happens the greater part of these articles are intensely personal, that is to say, while a newspaper man has to find something to write his daily or weekly article about, I have written articles entirely when the impetus came from within, in fact, I have cleaner hands in the case of non-fiction than in fiction. Let me add, however, if I had the time to sit down and make these over into a re-written book, rather than a revised book, I would devote that time to finishing Philippe. I simply can't afford to do it until I pull myself out of this pit of debt. Meanwhile, what do you think? I need advice on the subject.79

Ever yours,

Notes:

* “Princeton,” College Humor, December, 1927.

^ “What I Think and Feel at Twenty-Five,” American Magazine, September, 1922.

** “A Short Autobiography,” New Yorker, May 25, 1929.

++ “The Crack-up” (February), “Pasting It Together” (March), and “Handle With Care” (April), all published in 1936.

79. In his reply, dated April 8th, Perkins reiterated his feeling that the book would not be wise unless it were unified and revised into a volume of reminiscence. To publish the book Fitzgerald proposed, he pointed out, would “injure the possibilities of a reminiscent book at some later time.”

326. To Perkins

Cambridge Arms, Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland,

June 13, 1936.

Dear Max:

I am glad you agree with me about the Modern Library publishing “Tender Is The Night”. There was no intention of asking them about it before letting you know and I thought the two letters had gone off in the mail at the same time.80

However, the subject has reminded me of the idea that I wrote you about last month, to wit: the practicability of collecting my articles into a book, even without unifying them as an auto biography. The new series for Esquire seems to have moved Gingrich so much that he has written me that the one that appears in the August issue (called “Afternoon of An Author”) is the best thing he has published in six years of editing his sheet. I still think that if I could get an attractive title, that the book would have possibility. It would include very much the material I suggested before with the addition of these new Esquire pieces, and I would expect to do a certain amount of work on it in proof. Please reconsider the matter and let me know.81

My plans are still vague for the summer, but you can always reach me through the Cambridge Arms address.

Best wishes always,

Notes:

80. Fitzgerald had wired Donald Klopfer and Bennett Cerf of the Modern Library, suggesting that they publish Tender Is the Night. Klopfer had replied on May 19th that he was personally interested in the book but that he would have to await Cerf's return from England before a final decision could be made. On June 3rd, Perkins had written Fitzgerald that he too approved the idea.

81. On June 16th, Perkins replied in much the same vein as his earlier response of April 8th, but he ended the letter, “we shall do it [the book Fitzgerald proposed] if you think well of it, and do our best for it.”

327. TO: Earl Donaldson (Of the Sun Life Insurance Co.)

TL(CC), 1 p. Princeton University; Correspondence.

July 5, 1936

Dear Earl:

With the help of a suggestion of John Biggs Jr. I went to the Scribner Company and arranged to borrow enough to cover the two deficient payments of March 15 and June 15. From his office I called up your office in Newark, New Jersey and found that you are equipped to handle such assignments in emergencies. The time is short now because my interests must be protected before the fifteenth of July, and this is already the sixth; so would you send me the following documents which I must fill out?

(a) An assignment to the Charles Scribner Company, 599 Fifth Avenue, New York City, of first rights, in case of my death, of $1500.00 to them, I am told that you must send me three papers to be signed and assigned. Mr. Charles Scribner will, in return, pay you $1500.00 to cover the payments overdue on March 15 and June 15. According to your letter, it is important that all of this should be done before July 15, up to which time I am protected, after that I think I shall be able to carry the $700.00 per quarter. I don't want any slip up to happen here, because this is the only protection that my wife and child have.

(b) My life insurance might lapse for non-payment; therefore, I would like to have my policy changed so that the beneficiaries, in the event of my death, will be, first: Charles Scribner, to the amount of $1500.00; and second: Harold Ober, of 40 E. 49th Street, New York City, to the extent of $8,000.00, balance to go to such heirs and assigns as may be made in my will.

Please send all necessary forms in triplicate to provide for the Charles Scribner's Sons, and for Harold Ober, to reach me by special delivery here.

Ever yours,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

P.S. I am sending this registered mail and hope for a registered letter from you.

Cambridge Arms Apts, Baltimore, Md.

328. FROM: Charles Scribner

TL(CC), 2 pp. Princeton University; Correspondence.

July 10, 1936.

Dear Scott:

Eben Cross called me up on the telephone the first of the week and I sent him the cheque for $1,500.00 to pay your back insurance premiums. I also thought that it was a good time to check up on the advances we had made in order that no misunderstanding might ever arise.

Most of the ancient indebtedness was written off against the serial publication of “Tender is the Night” and the royalty advance on this book. The advance still stands us out $1,671.50 but this is of course only an obligation against “Tender is the Night.”

Since its publication we loaned you $2,000.00 which Ober thought would be met by the sale of motion-picture rights but unfortunately that never came off. On this it was agreed that you should pay 5% interest and it was not to be regarded as a charge against your account with us.

Your open account shows that we have advanced you from time to time $4,400.00 and that this has been reduced by the fact that you have earned since that time $1,188.99 in royalties. We have also paid $100.00 for customs duties which I do not know about personally, and for sundry charged $39.83 plus a bill in the retail of $390.03, and $77.22 interest on the $2,000.00.

Therefore, after deducting the unearned balance on “Tender is the Night,” there is a deficit in your account of $5,818.09, not taking into account the $1,500.00 which you have just assigned on your life insurance policies.

I have thought of asking you to include the loan of $2,000.00 in the assignment as there does not seem to be any prospect in the next few years that you will be able to take care of it, and had I known that Ober was willing to do so I would have spoken to you, but I rather hated to see your daughter's heritage cut down any.

All this is rather painful and I hope it will not give you a headache. Max and I thought it only fair, however, by you as well as ourselves to get the figures on paper, to make sure that we agreed with you.

I certainly hope that you may be able to find time to write a novel in the next few years but I can very well appreciate the difficulties you are up against.

I overlooked giving you a book which I thought might interest you and when you have a permanent address I wish you would let me know and I will send it on.

With all best wishes

Sincerely yours

329. To Perkins

Asheville, N.C., *

Sept. 19th, 1936

Dear Max:

This is my second day of having a minute to catch up with correspondence. Probably Harold Ober has kept you in general touch with what has happened to me but I will summarize:

I broke the clavicle of my shoulder, diving—nothing heroic, but a little too high for the muscles to tie up the efforts of a simple swan dive—At first the Doctors thought that I must have tuberculosis of the bone, but x-ray showed nothing of the sort, so (like occasional pitchers who throw their arm out of joint with some unprepared for effort) it was left to dangle for twenty-four hours with a bad diagnosis by a young Intern; then an x-ray and found broken and set in an elaborate plaster cast.

I had almost adapted myself to the thing when I fell in the bath-room reaching for the light, and lay on the floor until I caught a mild form of arthritis called “Miotoosis,” [myotosis] which popped me in the bed for five weeks more. During this time there were domestic crises: Mother sickened and then died and I tried my best to be there but couldn't. I have been within a mile and a half of my wife all summer and have seen her about half dozen times. Total accomplished for one summer has been one story—not very good, two Esquire articles, neither of them very good.

You have probably seen Harold Ober and he may have told you that Scottie got a remission of tuition at a very expensive school where I wanted her to go (Miss Edith Walker's School in Connecticut). Outside of that I have no good news, except that I came into some money from my Mother, not as much as I had hoped, but at least $20,000. in cash and bonds at the materialization in six months—for some reason, I do not know the why or wherefore of it, it requires this time. I am going to use some of it, with the products of the last story and the one in process of completion, to pay off my bills and to take two or three months rest in a big way. I have to admit to myself that I haven't the vitality that I had five years ago.

I feel that I must tell you something which at first seemed better to leave alone: I wrote Ernest about that story of his,** asking him in the most measured terms not to use my name in future pieces of fiction. He wrote me back a crazy letter, telling me about what a great Writer he was and how much he loved his children, but yielding the point—“If I should out live him—” which he doubted. To have answered it would have been like fooling with a lit firecracker.

Somehow I love that man, no matter what he says or does, but just one more crack and I think I would have to throw my weight with the gang and lay him. No one could ever hurt him in his first books but he has completely lost his head and the duller he gets about it, the more he is like a punch-drunk pug fighting himself in the movies.

No particular news except the dreary routine of illness.

Scottie excited about the wedding.

As ever yours,

Notes:

* Fitzgerald had moved to Asheville to be close to Zelda who was in a sanitarium there.

** “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” which, in its original version, had the hero thinking, “He remembered poor old Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of [the rich] and how he had started a story once that began, 'The very rich are different from you and me.' And how someone had said to Scott, yes they have more money. But that was not humorous to Scott.” In subsequent printings, the name was changed to Julian.

Ethel Walker School, Simsbury, Connecticut.

Also Turnbull.

330. To Fitzgerald

Sept. 23, 1936

Dear Scott:

If you are sure to get $20,000 in six months, doesn't this offer you your big chance? You have never, since the very beginning, had a time free from the necessity of earning money.—You have never been free from financial anxiety. Can't you now work out a plan to get at least eighteen months, or perhaps two years, free from worry by living very economically, and work as you always wanted to, on a major book? Certainly it seems to me that here is your opportunity. I am glad Scotty is doing so well. I know the school in Simsbury, once thought of sending our girls there. It is very good.

As for what Ernest did, I resented it, and when it comes to book publication, I shall have it out with him. It is odd about it too because I was present when that reference was made to the rich, and the retort given, and you were many miles away.

Always yours,

331. TO: Maxwell Perkins

Wire. Princeton University

ASHEVILLE NCAR 1936 OCT 6 AM 2 23

EVEN THOUGH ADMINISTRATOR HAS BEEN APPOINTED BALTIMORE BANK WILL NOT ADVANCE MONEY ON MY SECURITIES OF TWENTY THOUSAND I MARKET VALUE AT THEIR ESTIMATE UNTIL SIX WEEKS BY WHICH TIME I WILL BE IN JAIL STOP WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN YOU CANT PAY TYPIST OR BUY MEDICINES OR CIGARETTS STOP ANY LOANS FROM SCRIBNERS CAN BE SECURED BY LIEN PAYABLE ON LIQUIDATION CANT SOMETHING BE DONE I AM UP AND PRETTY STRONG BUT THESE ARE IMPOSSIBLE WRITING CONDITIONS I NEED THREE HUNDRED DOLLARS WIRED TO FIRST NATIONAL BALTIMORE AND TWO THOUSAND MORE THIS WEEK WIRE ANSWER1

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD.

Notes:

1 This loan was not made. See Perkins' 6 October letter to Fitzgerald in Scott /Max.

332. To Fitzgerald

Oct 6, 1936

Dear Scott:

We have been talking here for a long time as a result of getting your telegram.82 We have to have some business justification for the money we put out. With both Charlie* and me there is a strong personal element in the matter, but there is none, or hardly any, with others who do not know you and who cannot understand why your account should look as it does. How are we to explain it to them? We greatly want to help you and always have, but you do not half help us to do it. In this case, if we send you the two thousand, we should have some degree of justification if you could give us a guarantee from the administrator that this, and the earlier loan of two thousand for which we hold your note, would be paid on liquidation of the Estate. But we should feel much better about the whole thing, and about you yourself, if you could now, with the respite which this inheritance will give you, work out some plan by which you would be producing something upon which we might hope to realize,—and you would too. One successful book would clear the whole slate for you all round. Couldn't you now make a regular scheme by which you would produce a book? I am not at all sure but what that biographical book I urged upon you would not be the most likely one to do what is needed. But you will now have this interval of a year, and you ought to make the fullest use of the opportunity.

—If you only could tell us what you are planning, we should feel very much better about the whole matter,—and more on your account than on our own too.

Always yours,

Notes:

* Charles Scribner, President of Charles Scribner's Sons.

82. Fitzgerald had asked for $2,000. On October 6th, Perkins wired that he was sending $300, but added, “If we advanced more could you have administrator legally guarantee repayment[?]”

333. To Perkins

Grove Park Inn Asheville, N.C.

October 16, 1936

Dear Max:

As I wired you, an advance on my Mother's estate from a friend makes it unnecessary to impose on you further.

I do not like the idea of the biographical book. I have a novel planned, or rather I should say conceived, which fits much better into the circumstances, but neither by this inheritance nor in view of the general financial situation do I see clear to undertake it. It is a novel certainly as long as Tender Is The Night, and knowing my habit of endless corrections and revisions, you will understand that I figure it at two years. Except for a lucky break you see how difficult it would be for me to master the leisure of the two years to finish it. For a whole year I have been counting on such a break in the shape of either Hollywood buying Tender or else of Grisman getting Kirkland or someone else to do an efficient dramatization. (I know I would not like the job and I know that Davis* who had every reason to undertake it after the success of Gatsby simply turned thumbs down from his dramatist's instinct that the story was not constructed as dramatically as Gatsby and did not readily lend itself to dramatization.) So let us say that all accidental, good breaks can not be considered. I can not think up any practical way of undertaking this work. If you have any suggestions they will be welcomed, but there is no likelihood that my expenses will be reduced below $18,000 a year in the next two years, with Zelda's hospital bills, insurance payments to keep, etc. And there is no likelihood that after the comparative financial failure of Tender Is The Night that I should be advanced such a sum as $3,000. The present plan, as near as I have formulated it, seems to be to go on with this endless Post writing or else go to Hollywood again. Each time I have gone to Hollywood, in spite of the enormous salary, has really set me back financially and artistically. My feelings against the autobiographical book are:

First: that certain people have thought that those Esquire articles*** did me definite damage and certainly they would have to form part of the fabric of a book so projected. My feeling last winter that I could put together the articles I had written vanished in the light of your disapproval, and certainly when so many books have been made up out of miscellaneous material and exploited material, as it would be in my case, there is no considerable sale to be expected. If I were Negly Farson* and had been through the revolutions and panics of the last fifteen years it would be another story, or if I were prepared at this moment to “tell all” it would have a chance at success, but now it would seem to be a measure adopted in extremis, a sort of period to my whole career.

In relation to all this, I enjoyed reading General Grant's Last Stand,+ and was conscious of your particular reasons for sending it to me. It is needless to compare the force of character between myself and General Grant, the number of words that he could write in a year, and the absolutely virgin field which he exploited with the experiences of a four-year life under the most dramatic of circumstances. What attitude on life I have been able to put into my books is dependent upon entirely different field of reference with the predominant themes based on problems of personal psychology. While you may sit down and write 3,000 words one day, it inevitably means that you write 500 words the next.

I certainly have this one more novel, but it may have to remain among the unwritten books of this world. Such stray ideas as sending my daughter to a public school, putting my wife in a public insane asylum, have been proposed to me by intimate friends, but it would break something in me that would shatter the very delicate pencil end of a point of view. I have got myself completely on the spot and what the next step is I don't know.

I am going to New York around Thanksgiving for a day or so and we might discuss ways and means. This general eclipse of ambition and determination and fortitude, all of the very qualities on which I have prided myself, is ridiculous, and, I must admit, somewhat obscene.

Anyhow, that [thank] you for your willingness to help me. Thank Charlie for me and tell him that the assignments he mentioned have only been waiting on a general straightening up of my affairs. My God, debt is an awful thing!

Yours,

Heard from Mrs. Rawlings & will see her83

Notes:

* Playwright Owen Davis, who had done the dramatization of Gatsby.

* American journalist and novelist, known primarily for his autobiographical books of adventure.

^ By Horace Green, published by Scribners in 1936.

*** Three essays known collectively as “The Crack-Up.”

83. Perkins, in a letter of October 2nd, had told Fitzgerald that Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was nearby in North Carolina and was very interested in meeting him. Perkins recommended her highly as “a great deal of a person, both in intelligence and in personality,” and urged Fitzgerald to see her.

Also Turnbull.

334. TO: Maxwell Perkins

Wire. Princeton University

ASHEVILLE NCAR 1936 DEC 3 PM 7 44

CANT EVEN GET OUT OF HERE UNLESS YOU DEPOSIT THE REMAINING THOUSAND STOP IT IS ONLY FOR A COUPLE OF MONTHS STOP I HAVE COUNTED ON IT SO THAT I HAVE CHECKS OUT AGAINST IT ALREADY STOP PLEASE WIRE ME IF YOU HAVE WIRED IT TO THE BALTIMORE BANK STOP THE DOCTORS THINK THAT THIS SESSION OF COMPARATIVE PROSTRATION IS ABOUT OVER

SCOTT FITZGERALD.

335. To Perkins

[Oak Hall Hotel] [Tryon, North Carolina] [late in February, 1937]

Dear Max:

Thanks for your note and the appalling statement. Odd how enormous sums of $10,000 have come to seem lately—I can remember turning down that for the serialization of The Great Gatsby—from College Humor.

Well, my least productive & lowest general year since 1926 is over. In that year I did 1 short story and 2 chaps. of a novel—that is two chaps. that I afterwards used. And it was a terrible story. Last year, even though laid up 4 mos. I sold 4 stories & 8 Esq. pieces, a poor showing God knows. This year has started slowly also, same damn lack of interest, staleness, when I have every reason to want to work if only to keep from thinking. Havn't had a drink since I left the north. (about six weeks, not even beer) but while I feel a little better nervously it doesn't bring back the old exuberance. I honestly think that all the prizefighters, actors, writers who live by their own personal performances ought to have managers in their best years. The ephemeral part of the talent seems when it is in hiding so apart from one, so “otherwise” that it seems it ought to have some better custodian than the poor individual with whom it lodges and who is left with the bill. My chief achievment lately has been in cutting down my and Zelda's expenses to rock bottom; my chief failure is my inability to see a workable future. Hollywood for money has much against it, the stories are somehow mostly out of me unless some new [scourse /] source of material springs up, a novel takes money & time—I am thinking of putting aside certain hours and digging out a play, the ever-appealing mirage. At 40 one counts carefully one's remaining vitality and rescourses and a play ought to be within both of them. The novel & the autobiography have got to wait till this load of debt is lifted.

So much, & too much, for my affairs. Write me of Ernest & Tom & who's new & does Ring still sell & John Fox & The House of Mirth. Or am I the only best seller who doesn't sell?

The account, I know, doesn't include my personal debt to you. How much is it please?

I don't know at all about Brookfield. Never have heard of it but there are so many schools there. Someone asked me about Oldfields where Mrs. Simpson went and I'd never heard of that. Please write me—you are about the only friend who does not see fit to incorporate a moral lesson, especially since the Crack up stuff. Actually I hear from people in Sing Sing & Joliet all comforting & advising me.

Ever Your Friend

Notes:

Also Turnbull.

336. To Fitzgerald

March 3, 1937

Dear Scott:

In spite of the discouraging financial outlook, I thought your letter was fine. Maybe you really were the best diagno[s]tician of any,—maybe you best knew yourself. My urgency about doing the autobiographical book—which of course I thought would be extremely good and would sell—was part of one of my very cunning plots.—That is, I thought that if you wrote all about that period, and said your full say about it, you would get through with it all and step out into some fresh field without being directed back by the past. I do not think I am much of a psychologist, but maybe there was something in that side of the idea.

Hem was here last week, and on Saturday I saw him off for Spain on the Paris, along with Evan Shipman* and Sidney Franklin. I hope they won't all get into trouble over there. They seem to be quite bloodthirsty, although they are going strictly on business. Ernest has finished his novel,+ but won't deliver it to us until June. He says he will be out of Spain by May first.

Tom is turning out volumes of manuscript, but he is terribly worried about his lawsuits. The landlady who sued him won't settle, at least for the present. She is too furious with him.84

Edith Wharton doesn't sell except with “Ethan Frome”, and that excellently. Not “The House of Mirth” though, nor any of her other books. Nor does Ring sell to any extent. But John Fox does, and also Thomas Nelson Page.** We had an unusual experience with Marcia Davenport's novel, “Of Lena Geyer”. Most books today succeed from the start or never. And even successes seldom carry into a new year. Marcia started out badly, with little advance sale, and none of the breaks. Not even good reviews, really. She has had no great sale yet,—about 20,000—but almost half of that has come since Christmas…

I see you have a story in the new Post.^^

Always yours,

Notes:

* Poet and acquaintance of Hemingway. + To Have and Have Not, published by Scribners in 1937.

** American novelist and diplomat, known primarily for his romantic stories of the post-Civil War South.

++ “Trouble.”

84. Late in 1936, Scribners and Wolfe had gotten into a $125,000 libel suit brought on the allegation of a woman who claimed that she had been slanderously portrayed in Wolfe's short story “No Door” and was identifiable. The suit was eventually settled out of court.

337. To Fitzgerald

[Oak Hall Hotel] [Tryon, North Carolina]

[Before March 19, 1937]

Dear Max:

Thanks for the book—I don't think it was very good but then I didn't go for Sheean or Negley Farson either. Ernest ought to write a swell book now about Spain—real Richard Harding Davis reporting or better. (I mean not the sad jocosity of P.O.M. passages or the mere calendar of slaughter.) And speaking of Ernest, did I tell you that when I wrote asking him to cut me out of his story he answered, with ill grace, that he would—in fact he answered with such unpleasantness that it is hard to think he has any friendly feeling to me any more. Anyhow please remember that he agreed to do this if the story should come in with me still in it.

At the moment it appears that I may go to Hollywood for awhile, and I hope it works out. I was glad to get news of Tom Wolfe though I don't understand about his landlady. What?

Ever yours,

Scott

Write me again—I hear no news. On the wagon since January and in good shape physically.

Notes:

Foreign correspondent Vincent Sheean.

In Green Hills of Africa (Scribners, 1935), Hemingway referred to his wife Pauline as “Poor Old Mama” or “P.O.M.”

Wolfe’s landlady had brought a libel suit against him.

From Turnbull.

338. To Fitzgerald

March 19, 1937

Dear Scott:

As for Ernest, I know he will cut that piece out of his story. He spoke to me a while ago about it, and his feelings toward you are far different from what you seem to suspect. I think he had some queer notion that he would give you a “jolt” and that it might be good for you, or something like that. Anyhow, he means to take it out.85

Ober told me about the Hollywood possibility,* and I hope it goes through;—and as he told you, I took the liberty of sending three hundred to the Baltimore bank myself, in view of the situation.

I hope the Hollywood thing goes, but even if it does not, don't get discouraged now because your letters are beginning to look and sound the way they used to.

Always yours,

Notes:

* Fitzgerald had written in his previous letter, that he was considering a Hollywood offer.

85. Fitzgerald had written a few days earlier that when he had asked Hemingway to remove his name from “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” Ernest “answered, with ill grace, that he would—in fact he answered with such unpleasantness that it is hard to think he has any friendly feeling to me any more. Anyhow please remember that he agreed to do this if the story should come in with me still in it.”

339. To Perkins

[Oak Hall Hotel] [Tryon, North Carolina]

[ca. May 10, 1937]

Dear Max:

Thanks for your letter—and the loan. I hope Ober will be able to pay you in a few weeks.

All serene here and would be content to remain indefinately save that for short stories a change of scene is better. I have lived in tombs for years it seems to me—a real experience like the 1st trip to Loudon County usually means a story. As soon as I can I want to travel a little—its fine not having Scottie to worry over, love her as I do. I want to meet some new people. (I do constantly but they seem just the old people over again but not so nice.)

Ever your Friend

Thanks for the word about Ernest. Methinks he does protest too much. *

Notes:

* Perkins had written Fitzgerald about Hemingway, “... his feelings towards you are different from what you seem to suspect. I think he had some queer notion that he would give you a 'jolt' and that it might be good for you or something like that.”

Also Turnbull.

340. To Perkins

[The Garden of Allah Hotel] [Hollywood, Calif.]

[ca. July 15, 1937]

Dear Max:

Thanks for your letter—I was just going to write you. Harold has doubtless told you I have a nice salary out here tho until I have paid my debts and piled up a little security so that my “catastrophe at forty” wont be repeated I'm not bragging about it or even talking about it. The money is budgeted by Harold, as someone I believe Charlie Scribner recomended years ago. I'm sorry that the Scribner share will only ammount to $2500 or so the first year but that is while I'm paying back Harold who like you is an individual. The seconde year it will be better.

There are clauses in the contract which allow certain off periods but it postpones a book for quite a while.

Ernest came like a whirlwind, put Ernest Lubitch [Ernst Lubitsch] the great directer in his place by refusing to have his picture prettied up and remade for him a la Hollywood at various cocktail parties. I felt he was in a state of nervous tensity, that there was something almost religious about it. He raised $1000 bills won by Miriam Hopkins fresh from the gaming table, the rumor is $14,000 in one night.

Everyone is very nice to me, surprised & rather relieved that I don't drink. I am happier than I've been for several years.

Ever your Friend

Notes:

Also Turnbull.

341. To Perkins

[Garden of Allah Hotel] [Hollywood, Cal.]

[ca. August 20, 1937]

Dear Max:

Have heard every possible version* save that Eastman has fled to Shanghai with Pauline.^ Is Ernest on a bat—what has happened? I'm so damn sorry for him after my late taste of newspaper bastards. But is he just being stupid or are they after him politically. It amounts to either great indiscretion or actual persecution.

Thanks for my “royalty” report. I scarcely even belong to the gentry in that line. All goes beautifully here so far. Scottie is having the time of her young life, dining with Crawford, Scheerer ect, talking to Fred Astaire & her other heroes. I am very proud of her. And a granddaughter.** Max, do you feel a hundred?

Ever Your Friend

Notes:

* Of a scuffle in the Scribners offices between Hemingway and radical editor-critic Max Eastman, which is elaborately described in Perkins' letter of August 24th.

^ Mrs. Ernest Hemingway.

** Perkins had recently become a grandfather

Also Turnbull.

342. FROM Max Perkins TO HAMILTON BASSO

Aug. 23, 1937

Dear Ham :

I was glad to hear about Tom. I took the risk of paying a month’s rent on his apartment 1 because the agent has been threatening to dispossess him at any moment, for the last week, and I did not know what in the world would happen if all his manuscripts got thrown out on the sidewalk, or even put up for auction—which I believe the landlord is entitled to do, to the extent of the debt. Miss Nowell2 has been telegraphing and writing Tom, but has got no answer, and I think this means that he has been away and when he gets back he will send a check. I thought it would do Tom lots of good to get back into the mountains,3 but perhaps the great fame that he enjoys there, and the happiness of being among his own people, has not enabled him to work properly. It must have done him good in resting him, and I suppose John Barleycorn is not so ubiquitous in that region as in this.

I guess I wrote you that old Scott4 seems to be on the right road at last, and busy and paying his debts.

I look forward eagerly to seeing both of you.

Always yours,

Notes

1 Thomas Wolfe’s apartment at 49th Street and First Avenue.

2 Miss Elizabeth Nowell, literary agent, a friend of Wolfe’s.

3 Wolfe made a short trip to his home town, Asheville, North Carolina, during August, 1937.

4 F. Scott Fitzgerald.

343. To Fitzgerald

Aug. 24, 1937

Dear Scott:

Since the battle occurred in my office between two men whom I have long known, and for both of whom I was at the time acting as editor, I have tried to maintain a position of strict neutrality.—And I have said to every newspaperman, and to everyone that I did not know very well, that the “altercation” was a matter entirely between them, and that I had nothing to say about it. But here, for your own self alone, is what happened:

Max Eastman was sitting beside me and looking in my direction, with his back more or less toward the door, talking about a new edition of his “Enjoyment of Poetry”. Suddenly in tramped Ernest and stopped just inside the door, realizing I guess, who was with me. Anyhow, since Ernest had often told me what he would do to Eastman on account of that piece Eastman wrote,* I felt some apprehension.—But that was a long time ago, and everyone was now in a better state of mind. But in the hope of making things go well I said to Eastman, “Here's a friend of yours, Max.” And everything did go well at first. Ernest shook hands with Eastman and each asked the other about different things. Then, with a broad smile, Ernest ripped open his shirt and exposed a chest which was certainly hairy enough for anybody. Max laughed, and then Ernest, quite good-naturedly, reached over and opened Max's shirt, revealing a chest which was as bare as a bald man's head, and we all had to laugh at the contrast.—And I got all ready for a similar exposure, thinking at least that I could come in second. But then suddenly Ernest became truculent and said, “What do you mean of accusing me of impotence?” Eastman denied that he had, and there was some talk to and fro, and then, most unfortunately, Eastman said, “Ernest you don't know what you are talking about. Here, read what I said,” and he picked up a book on my desk which I had there for something else in it and didn't even know contained the “Bull in the Afternoon” article. But there it was, and instead of reading what Eastman pointed out, a whole passage, Ernest began reading a part of one paragraph, and he began muttering and swearing. Eastman said, “Read all of it, Ernest. You don't understand,—Here, let Max read it.” And he handed it to me. I saw things were getting serious and started to read it, thinking I could say something about it, but instantly Ernest snatched it from me and said, “No, I am going to do the reading,” and as he read it again, he flushed up and got his head down, and turned, and smack,—he hit Eastman with the open book. Instantly, of course, Eastman rushed at him. I thought Ernest would begin fighting and would kill him, and ran around my desk to try to catch him from behind, with never any fear for anything that might happen to Ernest. At the same time, as they grappled, all the books and everything went off my desk to the floor, and by the time I got around, both men were on the ground. I was shouting at Ernest and grabbed the man on top, thinking it was he, when I looked down and there was Ernest on his back, with a broad smile on his face.—Apparently he regained his temper instantly after striking Eastman, and offered no resistance whatever.—Not that he needed to, because it had merely become a grapple, and of course two big men grappling do necessarily fall, and it is only chance as to which one falls on top.—But it is true that Eastman was on top and that Ernest's shoulders were touching the ground,—if that is of any importance at all. Ernest evidently thinks it is, and so I am saying nothing about it.

When both Ernest and Eastman had gone, I spoke to the several people who had seen or heard, and all agreed that nothing would be said.

It seems that Max Eastman for some reason wrote out an account of the thing and that the next night at dinner, where there were a number of newspaper people and various others of that kind, read it aloud. Apparently he was urged to do it by his wife, and it was supposed that it would go no further. But of course it did go further, and reporters came to Eastman for it and he gave them his own story. His story appeared in the evening papers on Friday, and reporters were calling me up all day, and when, late in the afternoon, Ernest came in I told him this. The reporters represented the story as saying, as indeed it did imply, that Eastman had thrown him over my desk and bounced him on his head, etc. And Ernest talked to one of these reporters and then agreed to be interviewed by him, and then a number of others turned up. I was talking to different people outside all the time and did not know what Ernest said until I read it in the papers. He talked too much, and unwisely. It would have been better to have said nothing, but at the time it seemed as though Eastman's story should not appear without proper qualification. Ernest really behaved admirably the moment after he had struck the blow with the book. He then talked more the next day at the dock before he sailed. That is the whole story. I think Eastman does think that he beat Ernest at least in a wrestling match, but in reality Ernest could have killed him, and probably would have if he had not regained his temper. I thought he was going to.

I am glad everything is going well with you. In rather troubled times I often think of that with great pleasure,—and with admiration.

All this I am telling you about the fight is in strict confidence.

Always yours,

Notes:

* “Bull in the Afternoon,” New Republic, June 7, 1933.

344. To Perkins

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. Studios Culver City, Calif.

Sept. 3, 1937.

Dear Max:

Thanks for your long, full letter. I will guard the secrets as my life.

I was thoroughly amused by your descriptions, but what transpires is that Ernest did exactly the same asinine thing that I knew he had it in him to do when he was out here. The fact that he lost his temper only for a minute does not minimize the fact that he picked the exact wrong minute to do it. His discretion must have been at low ebb or he would not have again trusted the reporters at the boat.

He is living at the present in a world so entirely his own that it is impossible to help him, even if I felt close to him at the moment, which I don't. I like him so much, though, that I wince when anything happens to him, and I feel rather personally ashamed that it has been possible for imbeciles to dig at him and hurt him. After all, you would think that a man who has arrived at the position of being practically his country's most imminent [eminent] writer, could be spared that yelping.

All goes well—no writing at all except on pictures.

Ever your friend,

The Schulberg book * is in all the windows here.

Notes:

Hemingway had brawled with critic Max Eastman in Perkins’s office.

* They Cried a Little by Sonya Schulberg.

Also Turnbull.

345. To Perkins

Garden of Allah 8152 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California

March 4th, 1938

Dear Max:

Sorry I saw you for such a brief time while I was in New York and that we had really no time to talk.

My little binge lasted only three days, and I haven't had a drop since. There was one other in September, likewise three days. Save for that, I haven't had a drop since a year ago last January. Isn't it awful that we reformed alcoholics have to preface everything by explaining exactly how we stand on that question?

The enclosed letter is to supplement a conversation some time ago. It shows quite definitely how a whole lot of people interpreted Ernest's crack at me in “Snows of K.” When I called him on it, he promised in a letter that he would not reprint it in book form. Of course, since then, it has been in O'Brien's collection,^ but I gather he can't help that. If, however, you are publishing a collection of his this fall, do keep in mind that he has promised to make an elision of my name. It was a damned rotten thing to do, and with anybody but Ernest my tendency would be to crack back. Why did he think it would add to the strength of his story if I had become such a negligible figure? This is quite indefensible on any grounds.

No news here. I am writing a new Crawford picture, called “Infidelity.” Though based on a magazine story, it is practically an original. I like the work and have a better producer than before—Hunt Stromberg—a sort of one-finger Thalberg, without Thalberg's scope, but with his intense power of work and his absorption in his job.

Meanwhile, I am filling a notebook with stuff that will be of more immediate interest to you, but please don't mention me ever as having any plans. “Tender Is the Night” hung over too long, and my next venture will be presented to you without preparation or fanfare.

I am sorry about the Tom Wolfe business.* I don't understand it. I am sorry for him, and, in another way, I am sorry for you for I know how fond of him you are.

I may possibly see you around Easter.

Best to Louise.

Ever yours,

All this about The Snows is confidential.

Notes:

^ The Best Short Stories 1937 and the Yearbook of the American Short Story, edited by Edward J. O'Brien.

* Wolfe had left Scribners and was to have his future books published by Harpers.

Also Turnbull.

346. To Fitzgerald

March 9, 1938

Dear Scott:

I was mighty glad to get your letter. I'll bet you find the work out there very interesting. Don't get so you find it too interesting and stay in it. I don't believe anyone could do it better, and I should think doing “Infidelity” would be really worthwhile.

You know my position about Ernest's story “The Snows”.—Don't be concerned about it. We do aim to publish a book of his stories in the Fall and that would be in it. His play^ will presumably be put on in the Fall but I cannot find out definitely whether it has yet been arranged for. I think Ernest is having a bad time, by the way, in getting re-acclimated to domestic life, and I only hope he can succeed.

I am sending back the letter about Gatsby.—You might want to have it for some reason. What a pleasure it was to publish that! It was as perfect a thing as I ever had any share in publishing.—One does not seem to get such satisfactions as that any more. Tom was a kind of great adventure, but all the dreadful imperfections about him took much of the satisfaction out of it. I think that at bottom Tom has an idea now that he will go it alone, doing his own work, and if he could manage that, it would be the one and only way in which he could really achieve what he should.

Scott, I ought not to even breathe it to you because it will probably never turn out, but I have a secret hope that we could some day—after a big success with a new novel—make an omnibus book of “This Side of Paradise,” “The Great Gatsby,” and “Tender Is the Night” with an introduction of considerable length by the author. Those three books, besides having the intrinsic qualities of permanence, represent three distinct periods.—And nobody has written about any of those periods as well. But we must forget that plan for the present.

I understand about your brief holiday, and thought it was justified, and greatly enjoyed seeing you the little I did. I wish you were to be here on April first when we are giving a party for Marjorie Rawlings, whose “South Moon” you liked.—She has written one called “The Yearling” which the Book of the Month Club has taken for April.—I planned the party before the Club did take it, though. They also took “South Moon” but that only sold about 10,000 copies even so, because it appeared on the day the bank holiday began.

Yours,

Notes:

^ “The Fifth Column.”

347. To Fitzgerald

April 8, 1938

Dear Scott:

You know Ernest went back to Spain, and I think he did it for good reasons. He couldn't reconcile himself to seeing it all go wrong over there,—all the people he knew in trouble—while he was sitting around in Key West. It was a cause he had fought for and believed in, and he couldn't run out on it. So he went back for a syndicate, and he wrote me on his arrival in France ten days ago. He wrote from the ship, and in a quite different vein from what he ever did before, in apology for having been troublesome—which he hadn't been in any serious sense—and thanking me for “loyalty” and then sending messages to different people here, and also to you and John Bishop. In fact, his letter made me feel depressed all through the weekend because it sounded as if he felt as if he did not think he would ever get back from Spain.—But I haven't much faith in premonitions. Very few of mine ever developed. Hem seemed very well, and I thought he was in good spirits, but I guess he wasn't. I thought I would tell you that he especially mentioned you.

But the good news is that the play, which came right after the letter, is very fine indeed, and it shows he is going forward. At the end, after “Philip” has gone through all kinds of horrors and carried on an affair with a girl, Dorothy, who is living in a Madrid hotel writing trivial articles, he says to his side-partner, “There's no sense babying me along. We're in for fifty years of undeclared wars, and I've signed up for the duration. I don't exactly remember when it was, but I signed up all right.”

And then later the girl, who has disgusted him by turning up with a silver fox cape bought for innumerable smuggled pesetas, tries to persuade him to marry her, or anyhow to go off with her to all the beautiful places on the Rivera and Paris and all that. And Philip says finally, “You can go. But I have been to all those places and I have left them all behind, and where I go now I go alone, or with others who go there for the same reason I go.”

There isn't much to give you an idea from, but you have intuition, and you know Ernest. He has grown a lot in some way. I don't know where he is going either, but it is somewhere. But anyhow, I felt greatly moved by the play, but melancholy after his letter. One thing that worries him a lot is Evan Shipman who was in that foreign brigade, whatever they called it. Anything may have happened to him, and Ernest felt responsible about his being there. I hope everything will turn out all right, but I thought you would like to hear. Anyhow, the play is really splendid. It should be produced in September.

Always yours,

348. TO: Maxwell Perkins

TLS, 4 pp. Princeton University

Garden of Allah stationery.

Hollywood, California

PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL

April 23, 1938

Dear Max:

I got both your letters and appreciate them and their fullness, as I feel very much the Californian at the moment and, consequently, out of touch with New York.

The Marjorie Rawlings’ book fascinated me. I thought it was even better than “South Moon Under” and I envy her the ease with which she does action scenes, such as the tremendously complicated hunt sequence, which I would have to stake off in advance and which would probably turn out to be a stilted business in the end. Hers just simply flows; the characters keep thinking, talking, feeling and don’t stop, and you think and talk and feel with them.

As to Ernest, I was fascinated by what you told me about the play, touched that he remembered me in his premonitory last word, and fascinated, as always, by the man’s Byronic intensity. The Los Angeles Times printed a couple of his articles, but none the last three days, and I keep hoping a stray Krupp shell hasn’t knocked off our currently most valuable citizen.

In the mail yesterday came a letter from that exquisitely tactful co-worker of yours, Whitney Darrow, or Darrow Whitney, or whatever his name is. I’ve never had much love for the man since he insisted on selling “This Side of Paradise” for a dollar fifty, and cost me around five thousand dollars; nor do I love him more when, as it happened the other day, I went into a house and saw someone reading the Modern Library’s “Great Modern Short Stories” with a poor piece of mine called “Act Your Age” side by side with Conrad’s “Youth,” Ernest’s “The Killers” because Whitney Darrow was jealous of a copyright.

His letter informs me that “This Side of Paradise” is now out of print. I am not surprised after eighteen years (looking it over, I think it is now one of the funniest books since “Dorian Gray” in its utter spuriousness—and then, here and there, I find a page that is very real and living), but I know to the younger generation it is a pretty remote business, reading about the battles that engrossed us then and the things that were startling. To hold them I would have to put in a couple of abortions to give it color (and probably would if I was that age and writing it again). However, I’d like to know what “out of print” means. Does it mean that I can make my own arrangements about it? That is, if any publisher was interested in reprinting it, could I go ahead, or would it immediately become a valuable property to Whitney again?

I once had an idea of getting Bennett Cerf to publish it in the Modern Library, with a new preface. But also I note in your letter a suggestion of publishing an omnibus book with “Paradise,” “Gatsby” and “Tender.” How remote is that idea, and why must we forget it? If I am to be out here two years longer, as seems probable, it certainly isn’t advisable to let my name slip so out of sight as it did between “Gatsby” and “Tender,” especially as I now will not be writing even the Saturday Evening Post stories.

I have again gone back to the idea of expanding the stories about Phillippe, the Dark Ages knight, but when I will find time for that, I don’t know, as this amazing business has a way of whizzing you along at a terrific speed and then letting you wait in a dispirited, half-cocked mood when you don’t feel like undertaking anything else, while it makes up its mind. It is a strange conglomeration of a few excellent over-tired men making the pictures, and as dismal a crowd of fakes and hacks at the bottom as you can imagine. The consequence is that every other man is a charlatan, nobody trusts anybody else, and an infinite amount of time is wasted from lack of confidence.