Dear Scott/Dear Max

Correspondence of Scott Fitzgerald and Maxwell Perkins

Chapter 3: The Drunkard's Holiday (January 1927 - February 1935)

177. To Fitzgerald

Jan. 20, 1927

Dear Scott:

I am under great pressure to tell people two things about you:—where you are, and what is to be the name of your novel. Now the papers have told where you are, so I won't have to refuse as I have been doing because you said confidential in your wire.45 But how about the title of the novel? And by the way, I guess you are right about “The World's Fair”. It is certainly a good title, and I see how it would fit what you told me of the book, the scene and all. There is one good reason for announcing it. It would give you control over it. You would establish a sort of proprietorship. And I think it would help to arouse curiosity and interest in the novel too, which will before so very long begin to appear in Liberty.—But whatever you decide about that, write me a line to tell me when you will be back here.

As ever your friend,

P.S. Love to Zelda.

Notes:

45. Fitzgerald had gone to Hollywood early in January to write movie scenarios, wiring Perkins to that effect on January 4th and urging him to keep his whereabouts confidential.

178. To Fitzgerald

April 7, 1927

Dear Scott:

I do not know how I ever happened to let you go without getting your address. All I can remember is Brandywine 100, well as I do remember the grand old edifice you are living in, and the broad river roughened by conflict with the tide.*

I do not want to harass you about your book, which might be bad for it. But if we could by any possibility have the title, and some text, and enough of an idea to make an effective wrap, by the middle of April, we could get out a dummy. And even if all these things had to be changed, it would be worth doing this.—It may though, be impossible, and then we won't, because we know perfectly well that all these things are insignificant along side of writing the book undisturbed by mfg. questions.

Love to Zelda.

Yours as ever,

Notes:

* Early in April, the Fitzgeralds moved into Ellerslie, a Greek-revival mansion outside Wilmington.

179. TO: Maxwell Perkins

April 1927

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

“Ellerslie,” Edgemoor, Delaware

Dear Max:

I get continual requests for biographical data. Would it be very expensive to print a short pamphlet with two or three articles on me already published (Wilsons, Rosenfelds, Boyds—say about 12,000-15,000 words in all)—a picture or so, a few appreciations + a short bibliography. What would be the cost done in the cheapest way possible?

Hope you found the cane. Many thanks for deposit. Will send title + pages at 1st possible moment.2

Let me know about O'Hara's book. It was great to see you

No news. Working hard

Scott.

Notes:

1 A pamphlet was not published.

2 Perkins had requested the title and a sample of the text of Fitzgerald's novel in order to start designing the book. Fitzgerald submitted “The Boy Who Killed His Mother” as a working title.

180. To Fitzgerald

May 10, 1927

Dear Scott:

I had a letter from Hemingway saying that he was about to send off his stories for the book, “Men Without Women” but there is one story there called, “Up in Michigan” I think, which he says Liveright refused to publish in “In Our Time” and that it was on this account that he left Liveright. I think you spoke to Charlie Scribner about this story and said that it was ridiculous that he should think it could be published. Could you tell me about it some time? Certainly we cannot go as far as Liveright is willing to. At least, I look upon him as an extremist in that respect. On the other hand, Mrs. Hemingway told me that the story could be made acceptable even for conservatives, by striking out a few physiological details.

I made an excuse of the loss of your cane to send you a present, which will reach you in a day or two;—may already have reached you.^

I hope the book is going well.

As ever yours,

Notes:

^ Fitzgerald had apparently lost one of his favorite canes during a visit to New York.

181. To Perkins

Ellerslie Edgemoor Delaware

[ca. May 12, 1927]

Dear Max:

The cane was marvelous. The nicest one I ever saw and infinitely superior to the one mislaid. Need I say I value the inscription? This is the cane I shall never lose.

It seems a shame to put business into a letter thanking you for such a gift but just a line about Ernest. It is all bull that he left Liveright about that story. One line at least is pornographic, though please don't bring my name into the discussion. The thing is—what is a seduction story with the seduction left out. Yet if that is softened it is quite printable. However I trust your judgement, as he should.

I'm sorry about O'Hara. ** I imagined that this book wasn't as good as his first—however he doesn't seem to me now to be an indisputably good risk—he's mature and developed and ought to be doing first rate things, if ever.

(Explain to Hemmingway, why don't you, that while such an incident might be lost in a book, a story centering around it points it. In other words the material raison d'etre as oppossed to the artistic raison d'etre of the story is, in part, to show the physiological details of a seduction. If that were possible in America 20 publishers would be scrambling for James Joyce tomorrow.)

Thanks many times for looking for the old cane. It doesn't matter. I want to put off the pamphlet * for a month until I make up some misunderstandings with the men who wrote the articles

Many, many sincere thanks Max. I was touched when I found it at the station

Notes:

* Early in March, Fitzgerald had proposed that Scribners put together a pamphlet containing two or three articles on him, “a picture or so, a few appreciations & a short bibliography.” Perkins was enthusiastic about the idea and asked Fitzgerald to send along copies of the articles he wanted included.

** Unidentifiable.

Also Turnbull.

182. To Fitzgerald

June 2, 1927

Dear Scott:

I have been thinking much about the title, “The Boy Who Killed His Mother”.+ I do not think it is sensational in any objectionable sense whatever, and its very simplicity and directness, almost literalness, give it a value, and a distinction from most of your other titles. At the same time, I am not at all sure about it. You will probably think of other titles in the meantime, so that there will be several to select from.

Yours ever,

Notes:

^ Proposed for Fitzgerald's new novel, then in progress.

183. TO: Maxwell Perkins

September 1927

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

“Ellerslie,” Edgemoor, Delaware

Dear Max:

One million matters

(1) Terribly sorry you can't come down. How about the first wk. end in October. Will that suit you both—I do hope so. The last fortnight of Sept is bad for us.

(2) Thanks for the royalty report. You were nice to say what you said—too nice, alas, for I'm going to ask you, if you possibly can, to deposit for me $200.00. That still keeps it under 5000. Can you?

(3) What do you know of Hemmingway, save his marriage?

(4) I'm hoping now to finish the novel by the middle of November.

(5) This enclosed letter is self explanatory. The entire European vogue of Gatsby (except the Scandanavian rights) rests on the French translation which I paid Llona to make. Evidently what he feared has happened and it seems a shame I wasn't informed about it before money was accepted from the Knauer Verlag. I don't know what arrangement you made with them but I hope it wasn't an outright sale—in any case if it is possible I wish you'd cancel the matter + take up the enclosed contract instead as neither Victor Llona or I who inaugurated the whole European business with your authorization were consulted by Knauer and I'd much rather come out there under Joyces publisher and translated by a known good man. Do let me know at once what you can do. It is of vital importance to me as I feel I am going to have more + more a European public. Also please return Llona's letter.

No more now. Always Your Affectionate Friend

Scott

P.S. I love my cane. I carry nothing else.

184. FROM: Maxwell Perkins

TL (CC), 2 pp. Princeton University

Dec. 8, 1927

Dear Scott:

I am sorry you were troubled about that check for one hundred and fifty. When busy at other things, I thought a number of times of wiring you. I had it on my mind, but I thought, “He will know we did it anyhow.” Now I am enclosing a check in behalf of Ernest Hemingway on orders just received from him. We sent him a check for a thousand dollars the other day, although he had not asked for it, and he does not seem to want it much. He says he may not ever cash it, and that he finds he lives according to the amount he has, however little it may be. “Men without” has gone to 13,000. I shall see John Biggs tomorrow, and hear about how you get on.

By the way, if you want an easy and amusing exercise, do as I have done, and get a set of quoit—tennis. It is practically the same game as deck tennis, and can be put up even on a piazza,—although I do not think yours is wide enough. I have it on a piazza and play it almost every night. Half an hour a day would keep you pretty fit, I believe, and Zelda would like it.

Ever yours,

185. To Perkins

“Ellersie” Edgemoor, Delaware

[ca. January 1, 1928]

Dear Max:

Patience yet a little while, I beseech thee and thanks eternally for the deposits.46 I feel awfully about owing you that money—all I can say is that if book is serialized I'll pay it back immediately. I work at it all the time but that period of sickness set me back—made a break both in the book & financially so that I had to do those Post stories—which made a further break. Please regard it as a safe investment and not as a risk.

I have no news. I liked Some People by Nicolson & The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Also I loved John's book* and I saw your letter agreeing that its his best thing, & the most likely to go. Its really thought out—oddly enough its least effective moments are the traces of his old manner, tho on [the] whole its steadily & culminatively [cumulatively] effective thoroughout. From the first draft, which was the one I saw I thought he could have cut 2000 or 3000 words that was mere Conradian stalling around. Whether he did or not I don't know.

No news from Ernest. In the latest transition (Vol 9.) there is some good stuff by Murray Goodwin (unprintable here) & a fine German play.

Always Your Afft. Friend

Except for a three day break last week (Xmas) I have been on the absolute wagon since the middle of October. Feel simply grand. Smoke only Sanos. God help us all.

Notes:

* Seven Days Whipping by John Biggs.

46. On September 24th, Perkins had deposited $600 for Fitzgerald; on December 2nd, $250; and on December 7th, $150.

Also Turnbull.

186. To Fitzgerald

Jan. 3, 1928

Dear Scott:

I was delighted to get your letter. I heard from John Biggs that you were making a splendid come back. Did you get the game of deck tennis? That would put on the final touches. I think we ought all to be proud of the way you climbed on the water wagon. It is enormously harder for a man who has no office hours and has control of his own time,—and it is hard enough for anybody.

We feel no anxiety whatever about the novel. I have worried a little about the length of time elapsing between that and “The Great Gatsby”. By the way, I was talking to Conrad Aiken whose opinions are worth something, and his opinion of “The Great Gatsby” is as high as any. I told him how depressed we were at the first reviews, and how I really thought the book had been injured by them because it did not gain the immediate impetus that good reviews would have given. He said, “Well now everybody knows anyhow what it was, and what 'Gatsby' means.”

Wishing you and Zelda the best of New Years, I am,

Ever your friend,

187. To Fitzgerald

Jan. 24, 1928

Dear Scott:

We have just agreed to take on a collection of Morley Callaghan's stories.* Some of them are very good, and they are all the genuine thing. And so is he himself. He wants particularly to see you, and I told him to let me know two or three days in advance before he came down again, and that I felt pretty sure I could get you to come over. He has interesting ideas about writing, and a remarkably just sense of things. At the first glance he is not very prepossessing, but one sees after a couple of minutes of talk, that he is highly intelligent and responsive. He is writing a novel which I have seen in unfinished form, and believe will turn out well.

I was immensely impressed with John's story, and that in the face of a great deal of scepticism. I thought it would be good, but that it would lack the same things which “Demigods” did,—and those things are really essential to any sort of a success. I thought he might never acquire them. But this story is magnificently written, far better than “Demigods”. Who but John would ever attempt to make a story out of such materials…

I have not read “The Bridge of San Luis Rey” myself, although when it came out I sent copies to a number of people who I thought would know a good thing. Between ourselves, the extravagant praise of a certain contributor to the columns of the Magazine, rather put me off it.^ As he likes it, I suspect I might not. I did read “The Caballa” when it came out, and thought it most promising.

We can surely count on your novel for the fall, can't we? It must be very nearly finished now.

Ever your friend,

Notes:

* Published later in 1928 as Strange Fugitive.

^ Perkins may be referring here to William Lyon Phelps, then a regular book reviewer for Scribner's Magazine.

188. TO: Maxwell Perkins

After 24 January 1928

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

“Ellerslie,” Edgemoor, Delaware

Dear Max:

Novel not finished. Christ I wish it were! Thanks for Hemmingway's letter. Was Dudly Lunt's law book any good?1

That's fine about Morly Callagan.2 I'll come up but give me plenty of warning. I think he really has it—personality, or whatever it is. One can't be sure yet and I doubt if he's as distinctive a figure as Ernest (Gosh! hasn't he gone over big?)

Will you ask the bk. keeping dept. not to spare my shame but to send me my bi-ennial report, for the income tax?

As Ever Scott.

Notes:

1 Possibly Dudley Lunt's The Road to the Law, published in 1932.

2 Morley Callaghan, Canadian novelist whose short-story collection, Native Argosy, had just been accepted by Scribners. See Perkins' 24 January letter to Fitzgerald in Scott/Max.

189. FROM Max Perkins TO Roger Burlingame (Fragment)

June 20, 1928

<…>

Waldo Peirce1 has been hereabouts lately with plans for trying to do some writing, in which I have little faith—that is, I have little faith in his ever doing the writing, though I think it might well be excellent if he did it. His mother has died and he seems to be heir to a large part of Bangor, Maine, where he now is “established on the back piazza with an antiquated typewriter.” He went down to visit Hemingway in Florida and came back with a pocketful of photographs of himself and Hemingway and Dos Passos (who was there too) with fishes almost as big as themselves. He gave us a very fine, simple drawing of Hemingway’s head, and promised to do some studies of him.

Scott2 is now in Paris finishing his novel.3 He went there for that purpose because of the expense of living in this country, which compelled him many times to drop the novel in order to write short stories for the Post. He promises to be back in August with a complete manuscript.

<…>

Notes

1 The painter

2 F. Scott Fitzgerald.

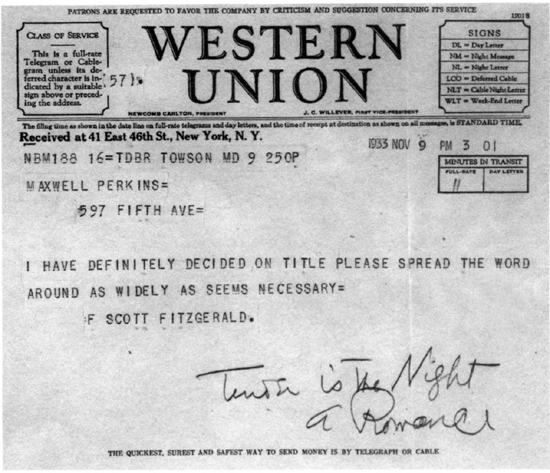

3 Tender Is the Night, Scribners, 1934.

190. To Fitzgerald

June 28, 1928

Dear Scott:

I am off tomorrow to Windsor for a month, but if you want anything from us, I think the most direct way to get it done would be to communicate with C.S., Jr. He will be here and will see to it.

I got from Ober your three boys' stories,47 and read them with great interest. Won't you have a book of them sometime? I thought the best part of any of them was that account of how the boys and girls met in a certain yard at dusk. That was beautifully done. That magical quality of summer dusk for young boys I have never before seen evoked. I hope you will be doing some more of these stories. I have just been having lunch with John Biggs, who said that Zelda wrote you were thinking of coming home,* he seemed to think, right away. I did not believe it though.

Ever your friend,

Notes:

* After unsuccessfully trying to finish his novel at Ellerslie, Fitzgerald and his family had gone to Europe for the summer.

47. Stories centering around the character of Basil Duke Lee. The three referred to are probably “The Scandal Detectives” (Saturday Evening Post, April 28, 1928), “A Night at the Fair” (Saturday Evening Post, July 21, 1928), and “The Freshest Boy” (Saturday Evening Post, July 28, 1928).

191. To Perkins

c/o Guaranty Trust Co. [Paris, France]

[circa July 1, 1928]

Dear Max:

We are settled and not a soul in the world knows where we are; on the absolute wagon and working on the novel, the whole novel and nothing but the novel. I'm coming back in August with it or on it. Thank you so much for the money—by this time Reynolds will have sold my last story and that, at French prices, will carry us through.

Please advise me as to the enclosure. Why not let's do it—you acting as my agent directly with him and keeping 10% thus saving Curtis Brown's 10%? Anyhow please advise me—I'd like to be published by him as he's done better than anyone in England with Americans.

I strongly advise your obtaining immediately the translation rights to

Les Hommes de la Route by Andre Chamson (Published by Bernard Grasset)

He's young, not salacious, and apparently is destined by all the solid literary men here to be the great novelist of France—no flash in the pan like Crevel, Radiguet, Aragon, etc. He has a simply astonishing reputation in its enthusiasm and solidity.

Yours as ever devotedly,

Scott

Thanks for the books at the boat—many thanks!

Notes:

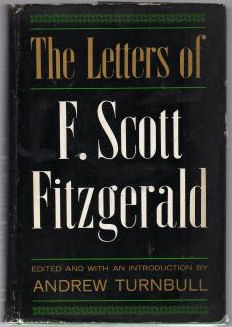

From Turnbull.

192. To Perkins

58 Rue de Vaugirard [Paris, France]

[ca. July 15, 1928]

Dear Max:

I read John Bishops novel. Of course its impossible. All the people who were impressed with Norman Douglass South Wind & Beerbohm's Zulieka Dobson tried to follow them in their wretched organization of material—without having either the brilliant intelligence of Douglass or the wit of Beerbohm. Vide the total collapse of Aldous Huxley. Conrad has been, after all, the healthy influence on the technique of the novel.

Anyhow at the same time Bishop gave me a novellette to read—and to my great astonishment, as a document of the Civil War its right up to Bierce & Stephen Crane—beautifully written, thrilling and water tight as to construction & interest. He's been so discouraged over the hash he made of the novel that he's been half afraid to send it anywhere & I told him that now that tales of violence are so popular I thought Scribners magazine would love to have a look at it.

So I'm sending it—no one has seen it but me. His adress is

Chateau de Tressancourt Orgeval, Seine et Oise

I'm working hard as hell

As Ever your friend

Notes:

Also Turnbull.

193. To Perkins

[58 rue de Vaugirard] [Paris, France] [ca. July 21, 1928]

Dear Max

(1) The novel goes fine. I think its quite wonderful & I think those who've seen it (for I've read it around a little) have been quite excited. I was encouraged the other day, when James Joyce came to dinner, when he said, “Yes, I expect to finish my novel in three or four years more at the latest” & he works 11 hrs a day to my intermittent 8. Mine will be done sure in September.48

(2) Did you get my letter about Andre Chamson?49 Really, Max, you're missing a great opportunity if you don't take that up. Radiguet was perhaps obscene—Chamson is absolutely not—he's head over heels the best young man here, like Ernest & Thornton Wilder rolled into one. This Hommes de la Route (Road Menders) is his 2nd novel & all but won the Prix Goncourt—the story of men building a road, with all the force of K. Hamsun's Growth of the Soil—not a bit like Tom Boyds bogus American husbandmen. Moreover, tho I know him only slightly and have no axe to grind, I have every faith in him as an extraordinary personality like France & Proust. Incidently King Vidor (who made The Crowd & The Big Parade) is making a picture of it next summer. If you have any confidence in my judgement do at least get a report on it & let me know what you decide. Ten years from now he'll be beyond price.

(3) I plan to publish a book of those Basil Lee Stories after the novel. Perhaps one or two more serious ones to be published in the Mercury or with Scribners if you'd want them, combined with the total of about six in the Post Series, would make a nice light novel, almost, to follow my novel in the season immediately after, so as not to seem in the direct line of my so-called “work.” It would run to perhaps 50 or 60 thousand words.

(4) Do let me know any plans of a) Ernest b) Ring c) Tom (reviews poor, I notice) d) John Biggs

(5) Did you like Bishops story? I thought it was grand.

(6) Home Sept 15th I think. Best to Louise

(7) About Cape—won't you arrange it for me and take the 10% commission? That is if I'm not committed morally to Chatto&Windus who did, so to speak, pick me up out of the English gutter. I'd rather be with Cape. Please decide and act accordingly if you will. If you don't I'll just ask Reynolds. As you like. Let me know.

Ever yr Devoted & Grateful Friend,

Notes:

48. Soon after his arrival in Paris, Fitzgerald had assured Perkins that he was “on the absolute wagon and working on the novel, the whole novel and nothing but the novel. I'm coming back in August with it or on it.”

49. Early in July, Fitzgerald had advised Perkins to obtain the translation rights to Chamson's Les Hommes de la Route, noting that the author was “young, not salacious, and apparently … destined by all the solid literary men here to be the great novelist of France.” The only French writer with whom Fitzgerald formed a friendship, Chamson became a Scribners author.

Also Turnbull.

194. To Fitzgerald

Aug. 6, 1928

Dear Scott: -

I was delighted to get that letter in which you said the novel was going so well. I returned from my vacation last Monday and would have written immediately except that I wanted also to have gotten somewhere with Chamson. The delay was not that I did not take action on your first mention of this, but that the book was in the hands of Mrs. Boyd* and she could not bring me a copy here. I finally got one myself through the bookstore. I ordered one from Paris on first hearing from you but they sent the wrong book,—“Essay, Man and History”. I have had the “Road Menders” read and shall now merely read enough of it to confirm, as I expect to do, the opinion of the reader which is high. Then we will try to make a deal with Mrs. Boyd. Mr. Scribner and all of us are most grateful to you for suggestions like this and we certainly do value your opinion. You never yet fell wrong that I know of.50 As for the “Bishop” I think it very fine but the magazine certainly cannot use it because of its length and I don't know what to do about it. I will write you fully within a few days. Ring's book will not come out until 1929, early. We thought it best to wait for a full collection and there are four copies that we can get into it by postponement. John Biggs has had good reviews but does not look like much of a sale. I am to see him on Thursday for lunch.

There are many more things I want to write you about but I am being as brief as I can because Miss Wyckoff^ is away and the stenographers here are all terribly over-worked.

Love to Zelda.

Ever your friend,

Notes:

* Probably literary agent Madeleine Boyd.

^ Irma Wyckoff (Mrs. Osmer Muench), Perkins' secretary.

50. On August 7th, Fitzgerald wired, “Knopf wants Andre Chamson. If you don't please wire before Friday.” Perkins' reply read, “Want Chamson. Making offer…”

195. TO: Maxwell Perkins

After 6 August 1928

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Paris

Dear Max:

Terribly sorry about Bishop.1 Delighted about Chamson.2 But this is very important!—The Road Menders is not accurate—they are not mending a road but pushing a new road thru + this becomes a great part of their lives; they are creaters + belong to their creation. Of course the difficulty of the literal “Men of the Road” is that it suggests Highwaymen to us. I suggest (without thinking any of these titles are good)

The Road Builders

The Road Makers

Creation

Toilers of the Road

Makers of the Road

Work on the Road3

In Haste Scott

Notes:

1 Perkins had declined to publish a novel by John Peale Bishop.

2 Andre Chamson, author of Les hommes de la route, whom Fitzgerald had recommended to Perkins. The novel was published by Scribners in 1929 as The Road.

3 See Perkins' 6 August letter to Fitzgerald in Scott/Max.

196. FROM Max Perkins TO ——

Aug. 28, 1928

Dear ——

We have read with interest your letter in criticism of “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and we thank you for it. Probably if you had read the book through, you would not have felt any the less repugnance to it, but you would no doubt have grasped its underlying motive, which is by no means opposed to your own point of view.

The author was prompted to write this book by surveying the tragic situation of many people because of the utter confusion of ideals into which they have fallen, with the result that they cannot distinguish the good from the bad. The author did not look upon these people with anger or contempt so much as with pity. He saw that good was in them, but that it was altogether distorted. He therefore pictured, in the Great Gatsby, a man who showed extraordinary nobility and many fine qualities, and yet who was following an evil course without being aware of it, and indeed was altogether a worshipper of wholly false gods. He showed him in the midst of a society such as certainly exists, of a people who were all worshipping false gods. He wished to present such a society to the American public so that they would realize what a grotesque situation existed, that a man could be a deliberate law-breaker, who thought that the accumulation of vast wealth by any means at all was an admirable thing, and yet could have many fine qualities of character. The author intended the story to be repugnant and he intended to present it so forcefully and realistically that it would impress itself upon people. He wanted to show that this was a horrible, grotesque, and tragic fact of life today. He could not possibly present these people effectively if he refused to face their abhorrent characteristics. One of these was profanity—the total disregard for, or ignorance of, any sense of reverence for a Power outside the physical world. If the author had not presented these abhorrent characteristics, he would not have drawn a true picture of these people, and by drawing a true picture of them he has done something to make them different, for he has made the public aware of them, and its opinion generally prevails in the end.

There are, of course, many people who would say that such people as those in the book should not be written about, because of their repulsive characteristics. Such people maintain that it would be better not to inform the public about evil or unpleasantness. Certainly this position has a strong case. There is, however, the other opinion: vice is attractive when gilded by the imagination, as it is when it is concealed and only vaguely known of; but in reality it is horrible and repulsive, and therefore it is well it should be presented as it is so that it may be so recognized. Then people would hate it, and avoid it, but otherwise they may well be drawn to it on account of its false charm.

Very truly yours,

197. TO: Maxwell Perkins

October/November 1928

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

“Ellerslie,” Edgemoor, Delaware

Dear Max:

Am going to send you two chapters a month of the final version of book beginning next week + ending in Feb.1 Strictly confidential. Don't tell Reynolds! I think this will help me get it straight in my own mind—I've been alone with it too long.

I think Stearns will be delighted + hereby accept for him.2 Send me a check made out to him—he hasn't had that much money since I gave him $50 in '25—the poor bastard. If you leave out his name leave out mine too—or as you like.

Ever Yrs Scott

Sending chapters Tues or Wed or Thurs.

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald sent only one installment of the novel.

2 Harold Stearns, “Apology of an Expatriate,” Scribner's Magazine (March 1929) — written in the form of a letter to Fitzgerald.

198. To Perkins

Edgemoor **

Nov '28

Dear Max:

It seems fine to be sending you something again, even though its only the first fourth of the book (2 chapters, 18,000 words). Now comes another short story, then I'll patch up Chaps. 3 & 4 the same way, and send them, I hope, about the 1st of December.

Chap. I. here is good

Chap II. has caused me more trouble than anything in the book. You'll realize this when I tell you it was once 27,000 words long! It started its career as Chap I. I am far from satisfied with it even now, but won't go into its obvious faults. I would appreciate it if you jotted down any critisisms—and saved them until I've sent you the whole book, because I want to feel that each part is finished and not worry about it any longer, even though I may change it enormously at the very last minute. All I want to know now is if, in general, you like it & this will have to wait, I suppose, until you've seen the next batch which finishes the first half. (My God its good to see those chapters lying in an envelope!)

I think I have found you a new prospect of really extraordinary talent in a Carl Van Vechten way. I have his first novel at hand—unfortunately its about Lesbians. More of this later.

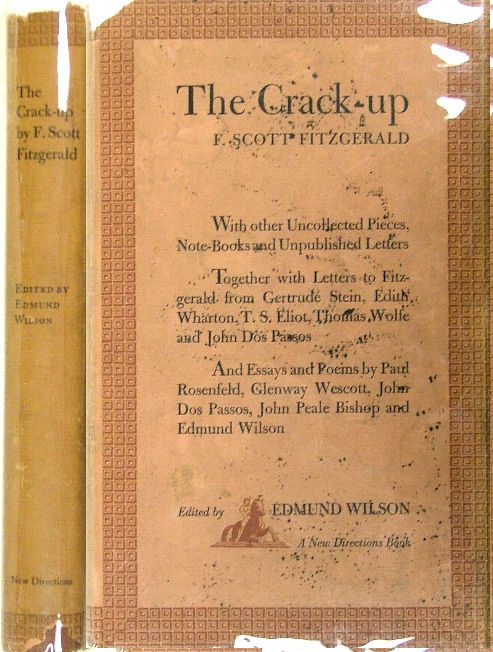

I think Bunny's title* is wonderful!

Remember novel is confidential, even to Ernest.

Always Yrs.

Notes:

** The Fitzgeralds had returned home late in September.

* I Thought of Daisy, a novel by Edmund Wilson, published by Scribners in 1929.

Also Turnbull.

199. To Fitzgerald

Nov. 13, 1928

Dear Scott:

I have just finished the two chapters. About the first we fully agree. It is excellent. The second I think contains some of the best writing you have ever done—some lovely scenes, and impressions briefly and beautifully conveyed. Besides it is very entertaining, including the duel. There are certain things one could say of it in criticism, but anyhow I will make no criticism until I read the whole book, and so see the relationships of the chapters. I think this is a wonderfully promising start off. Send on others as soon as you can.

I wish it might be possible to get this book out this spring, if only because it promises so much that it makes me impatient to see it completed.

Ever yours,

200. FROM: Maxwell Perkins

TL(CC), 2 pp. Princeton University

Jan. 23, 1929

Dear Scott:

I enclose a check for one hundred dollars which is from Ernest Hemingway in payment of that loan. He has also written, “Unless you come and get the book you can't have it,” so I expect to go and get it next week.1 Why don't you come too, and swear to stick with me and I will have you back inside of nine days. I would feel much safer with you too. Without you I may leave a leg with a shark, or do worse,—because alone I would lack the courage of my cowardice which would otherwise prompt me not to have anything to do with sharks. It seems Hemingway and Waldo2 have a theory that the sharks are more afraid of them than they are of the sharks,—but they are much more likely to be afraid of them than they are of me.

I am going to post an office boy sentry to watch the elevators to see when you come into this building and go out of it unless you break the habit of skipping the fifth floor.

Ever your friend,

Notes:

1 A Farewell to Arms (1929). Hemingway was in Key West, Fla.

2 Artist Waldo Peirce.

201. TO: Maxwell Perkins

February 1929

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Edgemoor, Dela

Dear Max

This is about four things

1st Can you have my “royalty” report sent me this week as I need it for my income tax. The last one Aug 1st 1928 with chivalrous delicacy does not mention the monies I had from you during 1928 and the government is insistant.

2nd Will you look out for a war book by one Wm. A. Brennan, a friend of a cousin of mine. It just might amount to something

3d Ditto in the case of a novel by Katherine Tighe Fessenden (Mrs. T. Hart Fessenden) who read proof on T. S. of P. + to whom I dedicated The Vegetable. Its her 1st novel + might be excellent. Will you let me know privately what you think of it?

4th Reynolds says Mr. Chas. Scribner was opposed to Cerf1 using one of my stories in a modern library collection to be called The Best Modern Short Stories; a 20th Century Anthology and to include Conrad, E. M Forster, D. H. Lawrence, Kath. Mansfield, Anderson + Maugham. In the cases of Hemmingway + Lardner who are chiefly known as short story writers I can see the objection, especially as they are still selling. But as my three collections sold about 150 books last year I don't see it makes much difference in a financial way.

Personally I should like very much to be in the collection—but there are only three or four short stories, Absolution, The Rich Boy, Benjamin Button, The Diamond as Big as the Ritz + May Day that I'd put in a book with the people I've mentioned—everything recently has a certain popular twist, even when its pretty good. So without your permission I'll have to forgo the matter. Please advise me.2

I'll be up next week

As Ever

Scott

Notes:

1 Bennett Cerf, a founding partner of Random House.

2 Great Modern Short Stories, ed. Grant Overton (1930), included Fitzgerald's “At Your Age” and Hemingway's “Three-Day Blow” but nothing by Ring Lardner.

202. To Perkins

[Ellerslie] [Edgetnoor, Delaware]

[ca. March 1, 1929]

Dear Max:

I am sneaking away like a thief without leaving the chapters—there is a weeks work to straighten them out & in the confusion of influenza & leaving, I havn't been able to do it. I'll do it on the boat & send it from Genoa. A thousand thanks for your patience—just trust me a few months longer, Max—its been a discouraging time for me too but I will never forget your kindness and the fact that you've never reproached me.

I'm delighted about Ernest's book—I bow to your decision on the modern library without agreeing at all. $100 or $50 advance is better than 1/8 of $40 for a years royalty, & the Scribner collection sounds vague & arbitrary to me. But its a trifle & I'll give them a new & much inferior story instead as I want to be represented with those men, ie Forster, Conrad, Mansfield ect.51

Herewith a manuscript I promised to bring you—I think it needs cutting but it just might sell with a decent title and no foreword. I don't feel certain tho at all—

Will you watch for some stories from a young Holger Lundberg who has appeared in the Mercury, he is a man of some promise & I headed him your way.

I hate to leave without seeing you—and I hate to see you without the ability to put the finished ms in your hands. So for a few months good bye & my affection & gratitude always

Notes:

51. Scribners had refused Random House permission to use a Fitzgerald story in a planned anthology, because, as Perkins explained in a letter of February 25th, the royalty proposed (one-half cent) “seemed like robbery.” He added that Scribners was planning their own similar anthology and that they would pay “2c apiece royalty.”

Also Turnbull.

203. To Perkins

[Paris]

[ca. April 1, 1929]

Dear Max:

This letter is too hurried to thank you for the very kind & encouraging one you wrote me. Its only to say—watch for a book on Baudelaire by Pierre Loving which Madeliene Boyd will bring you. I believe another one has been published but this man once did me a service & I promised to call your attention to it, before knowing it had a rival in the market.

I'm delighted about Ernest's novel.* Will be here in Paris trying as usual to finish mine, till July 1st. c/o The Guaranty Trust, Rue des Italiennes. Then the seashore.

A French man here (unfortunately I havn't his book at hand, but he's a well known writer on aviation) has written a book called “Evasions d'Aviateurs” dealing with aviators escapes during the war—all true & to me facinating. It's a best seller here now. In three months will come a sequel which will include some escapes of German & American aviators (as you know it was the tradition of all aviators to escape) which will include that of Tommy Hitchcock.

What would you say to the two in one oversized volume profusely illustrated with photographs? I believe Liberty had a great success with Richthoven & as a record of human ingenuity Les Evasions d'Aviateurs is astounding. To swell the thing a 3d book he has just published called Special Missions of Aviators during the War might be added. What do you think? It might just make a great killing like Trader Horn—it has a certain bizzare quality to divert the bored.

Unfortunately I havn't the man's name.

Again thank you for your kind and understanding letter. I'm ashamed of myself for whining about nothing & never will again.

Notes:

* A Farewell to Arms, published by Scribners in September, 1929.

Also Turnbull.

204. To Fitzgerald

April 12, 1929

Dear Scott:

I was certainly glad to get a letter from you and I immediately wrote Madeline Boyd to see if she could get through Bradley, an option on the book about the escapes of aviators. The Chamson has got beautiful reviews, but so far has not sold much;—but we are bringing out “Roux le Bandit” in the fall, and shall follow it by the other. I think we shall get the right results in the end. Don't think I do not—or that we do not—realize how much you have done for us apart from your own books. We fully appreciate it as a very great thing for us.—But the book we really want to publish is your book.

As for the last sentence of your letter, it ought not to have been written. You never did it so far as I know. You have always been to me the very model of courage.

Ever yours,

205. To Perkins

Villa Fleur des Bois Boulevard Eugene Gazagnaire (Till Oct 1st) Cannes.

[ca. June 1929]

Dear Max:

A line in haste to say

(1.) I am working night & day on novel from new angle that I think will solve previous difficulties

(2.) Dotty Parker, whos Big Blonde won O. Henry prize is writing a novelette or novel. She has been getting bad prices & I think, if she interested you she'd be glad to find a market in Scribners. Just now she's at a high point as a producer & as to reputation. You'd better get her Paris bank address from Bookman or New Yorker and have them forward, as I don't know when she'll leave here, where she's at Hotel Beau Rivage, Antibes. I wouldn't lose any time about this if it interests you.

(3.) Ernest's last letter a little worried, but I don't see why. To hell with the toughs of Boston. I hope to god All Quiet on the Western Front won't cut in on his sales. My bet is the book will pass 50,000.

(4) Deeply sorry about Ring.* Why won't he write about Great Neck, a sort of Oddysee of man starting in theatre business.

(5.) Do send me Bunny's book. I heard about his breakdown. I hope his poems include “Our Autumns were unreal with the new—”Please ask him about it—its haunted me for 12 years.

(6) Sorry about John's* leg—am writing him as I want news of the play.

(7) Tom Boyd has apparently dropped from sight, hasn't he. Do give me any news

Always Yr. Afft. Friend

Notes:

* Perkins had written on May 31st that Lardner's new book, Round Up, had sold 10,000 copies, with a prospect of 10,000 more, but that he seemed “dreadfully discouraged.”

* John Biggs.

Also Turnbull.

206. TO: Maxwell Perkins

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Villa Fleur des Bois Cannes

Sept 1st [1929]

Dear Max:

Working hard at the novel + have sworn not to come back this fall without completing it. Prospects bright. Two things.

(1) My clipping Bureau (The Author's) has gone out of business. Will you send me the adress of another.

(2) Most important—can you get me copies of The Great Gatsby in German, Swedish, Norwregan Danish ect. I should like very much to have them + if they go out of print never will even see them.' Can you take care of this for me?

Ever Yours Scott

207. To Fitzgerald

October 30, 1929

Dear Scott:

Weeks ago I began to hear rumors that you were about to sail for America,—in fact that you were then probably actually on the ocean. Then John Biggs began to think you would arrive any day,—probably at New Orleans.—But yesterday I had a letter from Ernest which spoke about you in a way which made me think you must be in Paris, and said nothing about your sailing at all, and so I am in hopes this letter may get there before you leave.

You will have heard about Ernest's book from him: it has sold just about 36,000 to date, and the only obstacle to a really big sale is that which may come from the collapse of the market,—what effect that will have nobody can tell. It may have a very bad effect on all retail business including that of books. No book could have been better received than his, and it has been the outstanding seller ever since it appeared. It has been pre-eminent. You may also have heard that Ring's play, “June Moon” based upon “Some Like 'Em Cold” and having songs for which Ring wrote both words and music, is a distinct success.—But this does not encourage me so much, because I am sure if Ring made a lot of money, he would do even less writing of the kind we can use, than even now.—And he is writing another play too, and once a man gets going at that, it is a question if he will ever do anything else, except by necessity. I hope you and Ernest will keep out of it.

I have seen several people lately who have seen you. One was Robert McAlmon.^ Ernest sent me a letter telling me he was coming, and so far as I could see the letter was entirely designed to help him, and there was no advantage to Ernest whatever in his meeting me. Ernest simply hoped that we would be able to do something for McAlmon as publishers, and yet when we got out to dinner what does McAlmon do but start in to say mean things about Ernest (this is absolutely between you and me) both as a man and as a writer. I can see that he might be envious, and that that was all the significance his talk had, but you would think even so, that when Ernest had brought us together, he might have laid off on him.

Another who had seen you was Callaghan.—He had seen you, he said, out of the corner of his eye while boxing with Ernest. He said you were meant to be keeping time, but that you were evidently thinking of something quite remote from boxing, and that he wondered if you ever would call the end of the round.

Bunny Wilson's book has sold about 3,000 and it is not going to have a large sale. What did you think of it? It did get excellent reviews and among a certain crowd made quite a hit,—but for the general public there is too much thought in it, or rather the thought and theory are too important and conspicuous elements in it. At least I suppose that is the trouble. We have been having quite an active and exciting season here with the life of Mrs. Eddy and the Christian Scientists living up to their great motto “All is love” by boycott and intimidation, which we have countered by advertising the fact that they were using these methods. You would have been much interested in this whole affair if you had been on hand. I sent Ernest a copy of the book,—or did I send you one? Then of course there was a certain amount of controversy over the “Farewell” out of which we seem to have come very successfully;—and the Wolfe book* of which I told you before you left here, is also stirring things up quite a bit.^

Notes:

^ American writer and editor.

* Later published as Look Homeward, Angel, by Thomas Wolfe.

^ Letter breaks off here, unsigned.

208. To Perkins

10 Rue Pergolese [Paris, France]

[ca. November 15, 1929]

Dear Max:

For the first time since August I see my way clear to a long stretch on the novel, so I'm writing you as I can't bear to do when its in one of its states of postponement & seems so in the air. We are not coming home for Xmas, because of expense & because it'd be an awful interruption now. Both our families are raising hell but I can't compromise the remains of my future for that.

I'm glad of Ring's success tho—at least its for something new & will make him think he's still alive & not a defunct semi-classic. Also Ernest's press has been marvellous & I hope it sells. By the way, McAlmon* is a bitter rat and I'm not surprised at anything he does or says. He's failed as a writer and tries to fortify himself by tieing up to the big boys like Joyce and Stien and despising everything else. Part of his quarrel with Ernest some years ago was because he assured Ernest that I was a fairy—God knows he shows more creative imagination in his malice than in his work. Next he told Callaghan* that Ernest was a fairy. He's a pretty good person to avoid

Sorry Bunny's book didn't go—I thought it was fine, & more interesting than better or at least more achieved novels.

Congratulations to Louise.

Oh, and what the hell is this book I keep getting clippings about with me and Struthers Burt and Ernest ect. As I remember you refused to let The Rich Boy be published in the Modern Library in a representative collection where it would have helped me & here it is in a book obviously fordoomed to oblivion that can serve no purpose than to fatigue reviewers with the stories. I know its a small matter but I am disturbed by the fact that you didn't see fit to discuss it with me.

However that's a rather disagreeable note to close on when I am forever in your debt for countless favors and valuable advice. It is because so little has happened to me lately that it seems magnified. Will you, by the way, send the Princeton book by Edgar—it's not available here. Did Tom Boyd elope? And what about Biggs' play?

Ever Yr. Afft Friend

* American writer and publisher, Robert McAlmon.

** Canadian writer, Morley Callaghan.

Notes:

A Farewell to Arms.

Canadian novelist Morley Callaghan was published by Scribners.

Present-Day American Stories (Scribners, 1929).

In Princeton Town (1929), by Day Edgar.

Also Turnbull.

209. FROM: Maxwell Perkins

TL(CC), 3 pp. Princeton University

November 20, 1929

Dear Scott:

Harold Ober was telling me today of a letter he had from you which said you would not come back until mid-February. Well, do come then anyhow. He told me the novel seemed to be going on, but I suppose we can hardly expect to publish until fall,—unless perhaps you will be sending it over before you yourself leave France.

I was terribly sorry to have to decline John Biggs'1 last book. It did not seem to have the life and power of his others;—and besides he had been Hemingway'd. Many young writers have, but one would not expect it of so marked an individual as John. He picked up the superficial traits of Ernest's method without anything else. It is possible, though, that this book represents a transition with John. He has probably outgrown his old fantastic phaze with its almost insane imaginative quality, and the next thing he writes may be much more natural, and if he gets into a new mood he may do better and also more successful things. I think he felt greatly disappointed, but I could not do anything else in his interests, even more than in ours.

Everything goes well to date with “A Farewell to Arms.” Ernest has cabled me several times to report on the sale, but it is hard to do it because there are always complications like those which come from dealers and jobbers splitting their orders so that part go into one month, and others into another, so that sometimes the sale is several thousand larger than the card actually shows. And yet I am always careful not to give an over-statement. In reality, between ourselves, the sale must now be 50,000, and perhaps more, but only about 47,000 show on the card. Somehow rumors very damaging to us have got about that Ernest is dissatisfied with his publisher. He knew about this before we did, and wrote me there was nothing in it whatever, but there is nothing that can be done to stop it, and every other house is perfectly willing to pass it on, and to take the excuse for going to Ernest with an offer. Here is one publisher rushing to him who, when “The Sun Also” appeared said of Scribners:— “A great publisher sunk to the gutter,” and another publisher sends over a delegation whose younger men read aloud passages from “The Sun Also” in derision, at a director's meeting. You would think they would be too ashamed of their original position to do this. I enclose herewith a paragraph from the Eagle which I suppose was written by a man who came in to see me to tell me that there was nothing in these reports of Ernest's dissatisfaction; and then he turns right around and puts into the paper something which will spread them everywhere. It is just an annoyance that can't be avoided, I suppose, but it is hurtful with writers in general who hear of it, as they all must.

I was impressed with McAlmon's “Village,”2 a copy of which he gave me. Some of the passages in it are very fine, but he does not seem to have any attractiveness of style, but rather the reverse. I think though, that if he will be patient, we shall be able to publish a book made up of some of the better things in “Village” and some other things which he has that he thinks will combine with these. I would certainly like to do this even on his own account because he is entitled to publication.—And I understand that he has had much to do with bringing other writers forward, although I never knew exactly what it was. Was he the originator and publisher of “Transition”?3

I hope you will send me a line some day, but don't do it if you are too busy. Remembrances to Zelda.4

Ever yours,

Notes:

1 Scribners had published two of Biggs' novels: Demigods (1926) and Seven Days Whipping (1928).

2 Village: As It Happened Through a Fifteen Year Period (1924).

3 McAlmon had slandered both Fitzgerald and Hemingway during his meeting with Perkins.

4 See Fitzgerald's c. 15 November letter to Perkins in Scott/Max.

210. To Fitzgerald

Nov. 30, 1929

Dear Scott:

I am sorry you feel as you do—and I understand why you feel as you do—about the collection of stories. The truth is I did not care much about the venture myself, but I see no harm in it at all, and the idea was that a collection like this could sell in school and college courses… I did speak to you about this collection, and you acquiesced in it in a letter you wrote me just before you sailed.

You may be right about wanting stories in the Modern Library, and it has been much on my mind that you should not have one of your best ones in if you have a story in at all. But what are regular publishers to do if all kinds of special sorts of publishers get out anthologies all the time, and come to them for their material and pay practically nothing for it, either to them or to the author. There are more of these demands for material for anthologies every year.—When a new publisher sets up, the very first thing he does is to try to get up an anthology of stories. I realize that the Modern Library is in a different position from others. It is a fine enterprise too, and good for the book business as a whole, in the long run.—But they come down upon us all the time with these requests, and it is hard to be making exceptions, and this book of theirs as originally planned, was over fifty percent made up of material published by Scribners.

I could not be glader of anything than of hearing how well you are going forward now. I know the book will be a great book, and you will have the most ardent support from every man here when it is ready.

Remembrances to Zelda. I am sending Scotty a copy of “American Folk and Fairy Tales”.

Ever your friend,

211. To Fitzgerald

Dec. 17, 1929

Dear Scott:

I am enclosing a letter I got from Callaghan, and a note which he sent to the Herald Tribune, and which was printed there. They will show you how things stand. The girl who started this story is one Caroline Bancroft. She wanders around Europe every year and picks up what she can in the way of gossip, and prints it in the Denver paper, and it spreads from there. Callaghan told me the whole story about boxing with Ernest, and the point he put the most emphasis on was your time-keeping. That impressed him a great deal. He did say that he knew he was more adept in boxing than Ernest, and that he had been practising for several years with fighters. He was all right about the whole matter. He is much better than he looks.52

…

Ernest's book should have sold very close to 70,000 by Christmas, and then the question is whether we can carry it actively on into the next season;—and that is chiefly a question because of the fact that we are evidently in for a period of depression. We have come out well here for the year—probably the best year we have had—but it is largely because of four or five very good books. Most books have failed this year, and most publishers have had bad years because of the fall season.

I hope you and Zelda will be coming back sometime early in 1930. Why don't you think of going down to Key West if I go in the spring?

Ever your friend,

Notes:

52. During the summer of 1929 in Paris, Fitzgerald had acted as unofficial timekeeper for a boxing match between Hemingway and Callaghan. He became so fascinated with the action of the match that he forgot to keep track of the time and only ended the round when Callaghan dropped Hemingway with a wild swing. Hemingway at first accused Fitzgerald of deliberately prolonging the round so that he could be beaten; but, according to Callaghan, all ended in an amicable drink at a nearby bar. Caroline Bancroft's account, in the Denver Post, inaccurately portrayed the match as the result of Hemingway's having spoken slightingly of Callaghan's knowledge of boxing. This same version was printed in the New York Herald Tribune Sunday Books Section by Isabel M. Paterson, on November 24, 1929.

212. To Perkins

10 Rue Pergolese Paris, France

Jan 21st 1930

This has run to seven long close-written pages so you better not read it when you're in a hurry.*

Dear Max: There is so much to write you—or rather so many small things that I'll write 1st the personal things and then on another sheet a series of suggestions about books and authors that have accumulated in me in the last six months.

(1.) To begin with, because I don't mention my novel it isn't because it isn't finishing up or that I'm neglecting it—but only that I'm weary of setting dates for it till the moment when it is in the Post Office Box.

(2) I was very grateful for the money*—it won't happen again but I'd managed to get horribly into debt & I hated to call on Ober, who's just getting started, for another centt

(3.) Thank you for the documents in the Callaghan case. I'd rather not discuss it except to say that I don't like him and that I wrote him a formal letter of apology. I never thought he started the rumor & never said nor implied such a thing to Ernest.

(4.) Delighted with the success of Ernest's book. I took the responsibility of telling him that McAlmon was at his old dirty work around New York. McAlmon, by the way, didn't have anything to do with founding Transition. He published Ernest's first book over here & some books of his own & did found some little magazine but of no importance.

(5) Thank you for getting Gatsby for me in foreign languages

(6) Sorry about John Biggs but it will probably do him good in the end. The Stranger in Soul Country had something & the Seven Days Whipping was respectable but colorless. Demigods was simply oratorical twirp. How is his play going?

(7.) Tom Boyd seems far away. I'll tell you one awful thing tho. Lawrence Stallings was in the West with King Vidor at a huge salary to write an equivalent of What Price Glory. King Vidor told me that Stallings in despair of showing Vidor what the war was about gave him a copy of Through the Wheat. And that's how Vidor so he told me made the big scenes of the Big Parade. Tom Boyd's profits were a few thousand—Stallings were a few hundred thousands. Please don't connect my name with this story but it is the truth and it seems to me rather horrible.

(8) Lastly & most important. For the English rights of my next book Knopf** made me an offer so much better than any in England (advance $500.00; royal[t]ies sliding from ten to fifteen & twenty; guaranty to publish next book of short stories at same rate) that I accepted of course.53 My previous talk with Cape was encouraging on my part but conditional. As to Chatto & Windus—since they made no overtures at my All the Sad Young Men I feel free to take any advantage of a technicality to have my short stories published in England, especially as they answered a letter of mine on the publication of the book with the signature (Chatto & Windus, per Q), undoubtedly an English method of showing real interest in one's work.

I must tell you (+ privately) for your own amusement that the first treaty Knopf sent me contained a clause that would have required me to give him $10,000 on date of publication—that is: 25% of all serial rights (no specifying only English ones,) for which Liberty have contracted, as you know, for $40,000. This was pretty Jewish, or maybe an error in his office, but later I went over the contract with a fine tooth comb + he was very decent. Confidential! Incidently he said to me as Harcourt once did to Ernest that you were the best publishers in America. I told him he was wrong—that you were just a lot of royalty-doctorers + short changers.

No more for the moment. I liked Bunny's book and am sorry it didn't go. I thought those Day Edgar stories made a nice book, didn't you?

Ever Your Devoted Friend

I append the sheet of brilliant ideas of which you may find one or two worth considering. Congratulations [on] the Eddy book.

(Suggestion List)

(1.) Certainly if the ubiquitous and ruined McAlmon deserves a hearing then John Bishop, a poet and a man of really great talents and intelligence does. I am sending you under another cover a sister story of the novelette you refused, which together with the first one and three shorter ones will form his Civil-War-civilian-in-invaded-Virginia-book, a simply grand idea & a new, rich field. The enclosed is the best thing he has ever done and the best thing about the non-combatant or rather behind-the-lines war I've ever read. I hope to God you can use this in the magazine—couldn't it be run into small type carried over like Sew Collins did with Boston & you Farewell to Arms? He needs the encouragement & is so worth it.

(2) In the new American Caravan amid much sandwiching of Joyce and Co is the first work of a 21 year old named Robert Cantwell. Mark it well, for my guess is that he's learned a better lesson from Proust than Thornton Wilder did and has a destiny of no mean star.

(3.) Another young man therein named Gerald Sykes has an extraordinary talent in the line of heaven knows what, but very memorable and distinguished.

(4) Thirdly (and these three are all in the whole damn book) there is a man named Erskine Caldwell, who interested me less than the others because of the usual derivations from Hemmingway and even Callaghan—still read him. He & Sykes are 26 yrs old. I don't know any of them.

If you decide to act in any of these last three cases I'd do it within a few weeks. I know none of the men but Cantwell will go quick with his next stuff if he hasn't gone already. For some reason young writers come in groups—Cummings, Dos Passos & me in 1920-21; Hemmingway, Callaghan & Wilder in 1926-27 and no one in between and no one since. This looks to me like a really new generation

(5) Now a personal friend (but he knows not that I'm [writing] you)—Cary Ross (Yale 1925)—poorly represented in this American Caravan, but rather brilliantly by poems in the Mercury & Transition, studying medicine at Johns Hopkins & one who at the price of publication or at least examination of his poems might prove a valuable man. Distincly younger that [than] post war, later than my generation, sure to turn to fiction & worth corresponding with. I believe these are the cream of the young people

(6) [general]* Dos Passos wrote me about the ms. of some protegee of his but as I didn't see the ms. or know the man the letter seemed meaningless. Did you do anything about Murray Godwin (or Goodwin?). Shortly I'm sending you some memoirs by an ex-marine, doorman at my bank here. They might have some documentary value as true stories of the Nicaraguan expedition ect.

(7.) In the foreign (French) field there is besides Chamson one man, and at the opposite pole, of great great talent. It is not Cocteau nor Arragon but young Rene Crevel. I am opposed to him for being a fairy but in the last Transition (number 18.) there is a translation of the beginning of his current novel which simply knocked me cold with its beauty. The part in Transition is called Mr. Knife and Miss Fork and I wish to God you'd read it immediately. Incedently the novel is a great current success here. I know its not yet placed in America & if you're interested please communicate with me before you write Bradley.

(8) Now, one last, much more elaborate idea. In France any military book of real tactical or strategical importance, theoretical or fully documented (& usually the latter) (and I'm not referring to the one-company battles between “Red” & “Blue” taught us in the army under the name of Small Problems for Infantry). They are mostly published by Payots here & include such works as Ludendorfs Memoirs; and the Documentary Preparations for the German break-thru in 1918 — how the men were massed, trained, brought up to the line in 12 hours in 150 different technical groups from flame throwers to field kitchens, the whole inside story from captured orders of the greatest tactical attack in history; a study of Tannenburg (German); several, both French & German of the 1st Marne; a thorough study of gas warfare, another of Tanks, no dogmatic distillations compiled by some old dotart, but original documents.

Now—believing that so long as we have service schools and not much preparation (I am a political cynic and a big-navy-man, like all Europeans) English Translations should be available in all academies, army service schools, staff schools ect (I'll bet there are American army officers with the rank of Captain that don't know what “infiltration in depth” is or what Colonel Bruckmuller's idea of artillery employment was.) It seems to me that it would be a great patriotic service to consult the war-department bookbuyers on some subsidy plan to bring out a tentative dozen of the most important as “an original scource [source] tactical library of the lessons of the great war.” It would be a parallel, but more essentially military rather than politico-military, to the enclosed list of Payot's collection. I underline some of my proposed inclusions. This, in view of some millions of amateurs of battle now in America might be an enormous popular success as well as a patriotic service. Let me know about this because if you shouldn't be interested I'd like to for my own satisfaction make the suggestion to someone else. Some that I've underlined may be already published.

My God—this is 7 pages & you're asleep & I want to catch the Olympic with this so I'll close. Please tell me your response to each idea.

Does Chamson sell at all? Oh, for my income tax will you have the usual statement of lack of royalties sent me—& for my curiosity to see if I've sold a book this year except to myself.

Notes:

* This note appeared above the salutation.

* On January 13th, Perkins had deposited $500 for Fitzgerald.

^ Harold Ober had recently disassociated himself from Paul Reynolds and was now starting on his own.

** Alfred A. Knopf, Ltd.

* These brackets are Fitzgerald's.

53. This agreement was terminated when Knopf dissolved their London house.

During the summer of 1929, Fitzgerald, acting as timekeeper for a sparring match between Hemingway and Callaghan, inadvertently allowed a round to run long, during which Callaghan knocked down Hemingway. This event was publicized and placed a strain on the Hemingway-Fitzgerald friendship. See Callaghan, That Summer in Paris (1963).

Knopf did not publish Tender Is the Night in England.

Bishop’s “The Cellar” had been rejected by Scribner’s Magazine, which then accepted “Many Thousands Gone” (September 1930). The novelette won the Scribner’s Magazine prize for 1930 and became the title story for Bishop’s first Charles Scribner’s Sons book in 1931.

Also Turnbull.

213. To Fitzgerald

Feb. 11, 1930

Dear Scott:

I enclose the royalty report. It was mighty good to get your long letter and all the suggestions, and I shall write you in detail about them this week. But as for the John Bishop story, I think it is a very, very fine thing, and although you must not say anything yet to him about it, I do hope we can work out a way of getting it into the Magazine. It is a hard proposition, for in a sense it is not a magazine kind of thing even in character. But it is a most unusual and impressive piece of work.

The Chamson stories have sold only about 2500 copies apiece. “The Crime of the Just” comes out pretty soon, and we may do better;—but anyhow, I am in hopes of publishing them all in one volume, and the very faint hope that we may be able to interest the Guild in the one volume. The stories are so short that they are at a disadvantage as separate books anyhow, and although they have had very warm reviews, they did not strike with a sufficient impact to get through to a sizeable public.—But when put together, they may well do more. Chamson tells us that he is writing a larger, and altogether different sort of novel. We have had very nice, sympathetic letters from him always.

I am trying to get in touch with Cantrell and Erskine Caldwell, and I shall let you know what comes of it.

I have here Crevell's “Etes-vous Fous” and I shall have the Transition, and I shall certainly communicate with you before the week is done. The military books I do not think we can go in for. We are pretty heavily embarked in literature relating to war, although quite different, of course, from that you speak of.—And there is even a large book on the whole military conduct of the war that we are involved with.—A fine book too, but a very large and difficult one. Besides, the American people do not believe there is ever going to be another war, apparently,—at least outside the Union Club and the Brevoort.

This letter is just a preliminary to a real answer. I have been so excessively busy that I have not been able to round things up as quickly as I had hoped.

Ernest went through, and seemed in fine shape. I swore I would go down to Key West in March,—and I do hope to do it for I have seldom liked a place as well.

Always your friend,

214. TO: Maxwell Perkins

After 11 February 1930

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Paris

Dear Max:

Just a last word about the Bishop story. He (and I too) is in doubt about the episode of the Union boy murdered + mutilated by the nigger. It is too melodramatic + not too clear, as the whole thing is already harrowing enough.

Will you consider the question of cutting it from the story. It is a short episode + not really important1

Ever

Scott

Notes:

1 “Many Thousands Gone” (Scribner's Magazine [September 1930]), which Fitzgerald had recommended to Perkins. The murder and castration of the soldier were retained in the story. See Perkins' 11 February letter to Fitzgerald in Scott /Max.

215. To Fitzgerald

March 14, 1930

Dear Scott:

I am off tomorrow for Key West where Mike Strater* also is, for two weeks. I wish you were here and could come too. Ernest is planning for a cruise up to the Everglades. If I ever go down there again after this year, and you are in this country, I shall keep after you until I get you to come along.

John Bishop writes that he told you about our accepting his story, but I wrote to you about it at the same time that I wrote to him. Since then I have seen both Cantwell, who is a very interesting fellow, and Caldwell. In fact we have taken two stories by Caldwell, though they are not up to his best. Cantwell submitted one which I enjoyed immensely in reading, but which we could not take partly because it was very long, and partly because it was one of those stories which do not make a clear, definite impression,—more of the sort that Katherine Mansfield often wrote in that respect. But it was beautifully done. I had lunch with him, and he is to send us others, but some friend of his had led him long ago to Farrar and Rhinehart, and they had accepted his first novel without seeing a line of it, which I do not think we could have done. Caldwell is also writing a novel, and although other publishers are after him now, I think we can probably have it.

Harold Ober yesterday gave me reason to hope that a large part of your novel would be here before long. I'll tell you when we get that into our hands, and a publication date set, we'll let loose everything we have got in the way of salesmanship and advertising. Everyone here is impatient to get that book and what is more, there is no author who commands a more complete loyalty than you do.

Ever your friend,

Notes:

*A painter and friend of Hemingway.

216. To Perkins

May 1930

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University; Life In Letters.

Paris

Dear Max:

I was delighted about the Bishop story—the acceptance has done wonders for him. The other night I read him a good deal of my novel + I think he liked it. Harold Ober wrote me that if it couldn’t be published this fall I should publish the Basil Lee stories, but I know too well by whom reputations are made + broken to ruin myself completely by such a move—I’ve seen Tom Boyd, Michael Arlen + too many others fall through the eternal trapdoor of trying cheat the public, no matter what their public is, with substitutes—better to let four years go by. I wrote young + I wrote a lot + the pot takes longer to fill up now but the novel, my novel, is a different matter than if I’d hurriedly finished it up a year and a half ago. If you think Callahgan hasn’t completely blown himself up with this death house masterpiece just wait and see the pieces fall. I don’t know why I’m saying this to you who have never been anything but my most loyal and confident encourager and friend but Ober’s letter annoyed me today + put me in a wretched humor. I know what I’m doing—honestly, Max. How much time between The Cabala + The Bridge of St Lois Rey, between The Genius + The American Tragedy between The Wisdom Tooth + Green Pastures. I think time seems to go by quicker there in America but time put in is time eventually taken out—and whatever this thing of mine is its certainly not a mediocrity like The Woman of Andros + The Forty Second Parallel. “He through” is an easy cry to raise but its safer for the critics to raise it at the evidence in print than at a long silence.

Ever yours

Scott

Notes:

Callaghan, Strange Fugitive (1928).

The Cabala (1926) and The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), by Thornton Wilder; The “Genius” (1915) and An American Tragedy (1925), by Theodore Dreiser; The Wisdom Tooth (1926) and The Green Pastures (1929), by Marc Connelly.

The Woman of Andros (1930), by Wilder; The 42nd Parallel (1930), by John Dos Passos.

Also Turnbull.

217. FROM: Maxwell Perkins

TL(CC), 2 pp. Princeton University

May 14, 1930

Dear Scott:

I hope Zelda is O.K. now. I am mighty sorry she was ill.1 You ought to spend next winter in Key West,—the healthiest, sunniest, restfullest place in the world (so far as I know it) and enough good company.

I have never found any flaw in your judgment about your work, yet. I think you are dead right in holding back the Basil Lee story until you get out the novel. The only thing that has ever worried me about you was the question of health. I know you have everything else, but I have often been afraid on that account, perhaps because I myself can stand so little in the way of late hours, and all that goes with them.

But don't blame me for being impatient once in a while. It is only the impatience to see something one expects greatly to enjoy and admire, and wishes to see triumph. That's the truth.

Ever yours,

Notes:

1 In April 1930 Zelda Fitzgerald suffered a nervous breakdown in Paris. While she was being treated at a Swiss clinic Fitzgerald shuttled between Switzerland and Paris, where Scottie was living with a governess.

218. To Perkins

[10 rue Pergolese] [Paris, France]

[May, 1930]

Dear Max:

First let me tell you how shocked I was by Mr. Scribner's death. It was in due time of course but nevertheless [I shall miss] his fairness toward things that were of another generation, his general tolerance and simply his being there as titular head of a great business.

Please tell me how this affects you—if at all.

The letter enclosed has been in my desk for three weeks as I wasn't sure whether to send it when I wrote it. Then Powell Fowler and his wedding party arrived and I got unfortunately involved in dinners and night clubs and drinking; then Zelda got a sort of nervous breakdown from overwork and consequently I haven't done a line of work or written a letter for twenty-one days.

Have you read The Building of St. Michele and D. H. Lawrence's Fantasia of the Unconscious? Don't miss either of them.

Always yours,

Scott

What news of Ernest?

Please don't mention the enclosed letter to Ober as I've written him already.

Notes:

The letter enclosed... - The Letter #163 of this collection

Brother of Ludlow Fowler.

The Story of San Michele (1929), by Axel Munthe.

From Turnbull.

219. To Perkins

[Switzerland]

[ca. July 8, 1930]

Dear Max:

I'm asking Harold Ober to offer you these three stories^ which Zelda wrote in the dark middle of her nervous breakdown. I think you'll see that apart from the beauty & richness of the writing they have a strange haunting and evocative quality that is absolutely new. I think too that there is a certain unity apparent in them—their actual unity is a fact because each of them is the story of her life when things for awhile seemed to have brought her to the edge of madness and despair. In my opinion they are literature tho I may in this case read so much between the lines that my opinion is valueless. (By the way Caldwell's stories were a throrough disappointment, wern't they—more crimes committed in Hemmingway's name)

Ever yours

Notes:

^ “A Workman,” “The Drouth and the Flood” and “The House.”

Also Turnbull.

220. To Fitzgerald

July 8, 1930

Dear Scott:

There is nothing so futile as telling a person you are sorry for things that have happened,—particularly when the person is one who knows how sorry you would be. I do hope Zelda is getting on. It is too bad. You certainly have a lot on your hands. We got the cable, and have replied that the fifteen hundred was deposited.

Ernest was here a while ago to meet Bumby,* who had come over with Ernest's sister-in-law. Ernest was very well, and we had some good times. We managed to take over from Liveright “In Our Time” and we shall re-issue that, and I believe will do quite well with it. On account of the circumstances it was published in, it never had a good show, and I think we could almost give it the effect of a new book, for the general public.

John Bishop sent over another story which was too long, and was not otherwise quite right for magazine publication, but he shortened it, and changed it in the other ways, and I think it is a very fine story.—Certainly it is a beautiful piece of writing.

Business never was worse, but people begin to think it will pick up in the fall.... We came out much better than most people this spring because of S. S. Van Dine,+ whose books seem not to have been affected by the depression,—in fact, almost to have gained by it. The booksellers seemed to think that they could sell it, and only it, and concentrated upon it.

Hoping that things will soon be better with you all, and that you may be back here, I am,

Ever your friend,

Notes:

* Nickname of John, Hemingway's oldest son.

+ Pen-name of Willard Huntington Wright, author of the Philo Vance mystery stories.

221. To Perkins

[Switzerland]

[circa July 20, 1930]

Dear Max: