Dear Scott/Dear Max

Correspondence of Scott Fitzgerald and Maxwell Perkins

Chapter 2: Trimalchio (April 1924 - December 1926)

102. To Perkins

Great Neck [Long Island]

[ca. April 10, 1924]27

Dear Max:

A few words more relative to our conversation this afternoon. While I have every hope & plan of finishing my novel in June you know how those things often come out. And even [if] it takes me 10 times that long I cannot let it go out unless it has the very best I'm capable of in it or even as I feel sometimes, something better than I'm capable of. Much of what I wrote last summer was good but it was so interrupted that it was ragged & in approaching it from a new angle I've had to discard a lot of it—in one case 18,000 words (part of which will appear in the Mercury as a short story).^ It is only in the last four months that I've realized how much I've—well, almost deteriorated in the three years since I finished the Beautiful and Damned. The last four months of course I've worked but in the two years—over two years—before that, I produced exactly one play, half a dozen short stories and three or four articles—an average of about one hundred words a day. If I'd spent this time reading or travelling or doing anything—even staying healthy—it'd be different but I spent it uselessly, niether in study nor in contemplation but only in drinking and raising hell generally. If I'd written the B & D at the rate of 100 words a day it would have taken me 4 years so you can imagine the moral effect the whole chasm had on me.

What I'm trying to say is just that I'll have to ask you to have patience about the book and trust me that at last, or at least for the 1st time in years, I'm doing the best I can. I've gotten in dozens of bad habits that I'm trying to get rid of.

1. Laziness.

2. Referring everything to Zelda—a terrible habit, nothing ought to be referred to anybody until its finished

3. Word consciousness—self doubt

ect. ect. ect. ect.

I feel I have an enormous power in me now, more than I've ever had in a way but it works so fitfully and with so many bogeys because I've talked so much and not lived enough within myself to develop the nessessary self reliance. Also I don't know anyone who has used up so much personal experience as I have at 27. Copperfield & Pendennis were written at past forty while This Side of Paradise was three books & the B. & D. was two. So in my new novel I'm thrown directly on purely creative work—not trashy imaginings as in my stories but the sustained imagination of a sincere and yet radiant world. So I tread slowly and carefully & at times in considerable distress. This book will be a consciously artistic achievement & must depend on that as the 1st books did not.

If I ever win the right to any liesure again I will assuredly not waste it as I wasted this past time. Please believe me when I say that now I'm doing the best I can.

Yours Ever

Notes:

^ “Absolution,” published in June 1924.

27. Between January and April, Fitzgerald, living in Great Neck, Long Island, worked on his novel. On April 1st, Perkins asked if he had decided on a title so that advance publicity material could be prepared. The title which Fitzgerald proposed was “Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires,” but Perkins, on April 7th, opposed this, noting that “The weakness is in the words 'Ash Heaps' which do not seem to me to be a sufficiently definite and concrete expression of that part of the idea.”

Also Turnbull.

103. To Fitzgerald

April 16, 1924

Dear Scott:

I delayed answering your letter because I wanted to answer it at length. I was delighted to get it. But I have been so pressed with all sorts of things that I have not had time to write as I meant and I am not doing so now. I do not want to delay sending some word on one or two points.

For instance, I understand exactly what you have to do and I know that all these superficial matters of exploitation and so on are not of the slightest consequence along side of the importance of your doing your very best work the way you want to do it;—that is, according to the demands of the situation. So far as we are concerned, you are to go ahead at just your own pace, and if you should finish the book when you think you will, you will have performed a very considerable feat even in the matter of time, it seems to me.

My view of the future is—particularly in the light of your letter—one of very great optimism and confidence.

The only thing is, that if we had a title which was likely, but by no means sure to be the title, we could prepare a cover and a wrap and hold them in readiness for use. In that way, we would gain several weeks if we should find that we were to have the book this fall. We would be that much to the good. Otherwise we should have done no harm. If we sold the book under a title which was later changed, no harm would have been done either. I always thought that “The Great Gatsby” was a suggestive and effective title,—with only the vaguest knowledge of the book, of course. But anyway, the last thing we want to do is to divert you to any degree, from your actual writing, and if you let matters rest just as they are now, we shall be perfectly satisfied. The book is the thing and all the rest is inconsiderable beside it.

Yours,

104. To Fitzgerald

June 5, 1924

Dear Scott:

I was mighty glad to hear from you to say you had arrived, and I did whatever you asked me to do in the store—I have forgotten what it was—and then to get Zelda’s very spirited and amusing letter.

I am glad you are deep in Milton [means: Shelley] and Byron. Trevelyan wrote an exceedingly interesting book about both of them—perhaps you have read it. I came across it in college. He told about how Shelley not only had that physical peculiarity which prevented his heart from burning, but that other one of sinking to the very bottom of a pool when Trevelyan told him that all a man needed to swim was self-confidence. No ordinary human being would, of course, sink to a depth of more than three feet or so. There was also a most interesting book by James Hogg about Shelley. Oh, I was a great Shelley fan, and I never fully got over it, though people think badly of him now.

I read your story in the Mercury ** and it seemed to me very good indeed, and also different from what you had done before,—it showed a more steady and complete mastery, it seemed to me. Greater maturity might be the word. At any rate it gave me a more distinct sense of what you could do,—possibly because I have not read any of your other stories in the magazines except “How to Live on Thirty-six Thousand”* which of course was a trifle. This seemed to show a remarkable strength and resource. I was greatly impressed by it.

Did you get the “War and Peace”? Don't feel any obligation to read it because it is better that you should follow your inclination, and time is valuable. The reason I mention it is that it did not get on the steamer^ in spite of the assurances of office boys, etc., that it would, and so I had to send it by mail.

The reason I went down to Ring Lardner's—but I am ashamed to tell you about it. I meant to have a serious talk with him, but we arrived late and the drinks were already prepared. We did no business that night. He was very amusing. The book* is out—you will have had your copy of it. The reviews have been excellent and so far as the reviewers are concerned, the title got across perfectly. I will pick out a bunch of clippings and send them after certain others like H.L.M.^ have been heard from. So far there has not been much of a sale, but all the publicity we have got ought to accomplish something for us. ...

Yours,

Notes:

** “Absolution” in American Mercury, June, 1924

* “How to Live on $36,000 a Year,” an article published in the Saturday Evening Post, on April 5, 1924.

^ The Fitzgeralds had sailed for Europe for the summer.

* How to Write Short Stories [With Samples] by Ring Lardner.

^ American journalist, essayist and literary critic H. L. Mencken.

105. To Perkins

Villa Marie, Valescure St. Raphael, France

June 18th, 1924

Dear Max:

Thanks for your nice long letter. I'm glad that Ring's* had good reviews but I'm sorry both that he's off the wagon & that the books not selling. I had counted on a sale of 15 to 25 thousand right away for it.

Shelley was a God to me once. What a good man he is compared to that collosal egotist Browning! Havn't you read Ariel yet? For heaven's sake read it if you like Shelley. Its one of the best biographies I've ever read of anyone & its by a Frenchman. I think Harcourt publishes it. And who “thinks badly” of Shelley now?

We are idyllicly settled here & the novel is going fine—it ought to be done in a month—though I'm not sure as I'm contemplating another 16,000 words which would make it about the length of Paradise—not quite though even then.

I'm glad you liked Absolution. As you know it was to have been the prologue of the novel but it interfered with the neatness of the plan. Two Catholics have already protested by letter. Be sure & read “The Baby Party” in Hearsts & my article in the Woman's Home Companion.**

Tom Boyd wrote me that Bridges had been a dodo about some Y.M.C.A. man—I wrote him that he oughtn't to fuss with such a silly old man. I hope he hasn't—you don't mention him in your letter. I enjoyed Arthur Trains story in the Post but he made three steals on the 1st page—one from Shaw (the Arabs remark about Christianity) one from Stendahl & one I've forgotten. It was most ingeniously worked out. I never could have handled such an intricate plot in a thousand years. War & Peace came—many thanks & for the inscription too. Don't forget the clippings. I will have to reduce my tax in Sept.

As Ever, Yours

P.S. If Struthers Burt* comes over give me his address.

Notes:

** “Wait Till You Have Children of Your Own.”

* A poet, essayist and novelist whose works were published by Scribners. Perkins had expressed the hope that Burt and Fitzgerald would meet.

*** How to Write Short Stories.

Also Turnbull.

106. To Perkins

Villa Marie Valescure St. Raphael, France

[ca. July 10, 1924}

Dear Max:

Is Ring dead? We've written him three times & not a word. How about his fall book. I had two suggestions. Either a collection called Mother Goose in Great Neck (or something nonsensical, to include his fairy tales in Hearsts, some of his maddest syndicate articles, his Forty-niners' Sketch, his Authors League Sketch ect.

—or “My Life and Loves” (Privately printed for subscribers only—on sale at all bookstores). I believe I gave you a tentative list for that but he'd have to eke it out by printing some new syndacate articles that way. I thought his short story book was great—Alibi Ike, Some Like 'em Cold & My Rooney are as good almost as the Golden Honeymoon. Menckens review was great. Do send me others. Is it selling?

Would you do me this favor? Call up Harvey Craw, 5th Ave—he's in the book and ask him if my house is rented. I'm rather curious to know & letters bring me no response. He is the Great Neck agent.

I'm not going to mention my novel to you again until it is on your desk. All goes well. I wish your bookkeeper would send me the August statement even tho no copies of my book have been sold. How about Gertrude's Steins novel?^ I began War & Peace last night. So write me a nice long letter.

As Ever

Notes:

^ The Making of Americans, then running serially in the Transatlantic Review.

Also Turnbull.

107. To Fitzgerald

August 8, 1924

Dear Scott:

I had yesterday a disillusioning afternoon at Great Neck, not in respect to Ring Lardner, who gains on you whenever you see him, but in respect to Durant's where he took me for lunch. I thought [about] that night a year ago that we ran down a steep place into a lake. There was no steep place and no lake. We sat on a balcony in front. It was dripping hot and Durant took his police dog down to the margin of that puddle of a lily pond,—the dog waded almost across it;—and I'd been calling it a lake all these months. But they've put up a fence to keep others from doing as we did.

About the renting of your house, which has been accomplished, you have heard from Ring Lardner, who says he will see you at Hyeres during September. He did not look well and he coughed. He ate almost nothing and smoked while he ate that. He ordered high-balls. I said I didn't want anything at all; but he stuck to one for himself and so later I took one. I saw no further use in denying myself. We had a number. But Ring told me that to-morrow he would drop both liquor and nicotine so as to do enough work to go safely abroad. He won't drop the strip:—the artist hasn't an idea in his head and counts upon Ring for his living;—is even building a house on the strength of the association. I'd gone through Ring's syndicate articles and found much good in them; and he told me of articles in Liberty and then there are the Hearst articles. I proposed a book selection from all these,—I to select and he to approve, or otherwise; and of this he thought well. But that's for 1925: we hope to carry over the stories through the fall and have planned advertising for mid-August. This Sunday there's to be an excellent ad in the Times. I'll send it over.

Then I proposed that we try to acquire the Doran and Bobbs Merrill books28 ourselves,—if possible, by frank but tactful correspondence, and get prefaces for them and carry them on our lists for the trade and at the same time form a set of five volumes:-a magazine and subscription set such as you first proposed. He thought well of this.

Then I said, “Ring, if it were a matter of money we would be willing to help toward a novel, you know. But I judge the $5,000 or so we'd gladly put up wouldn't count.” And of course he said it wasn't at all a question of money:—but I wanted him to know we were ready to back him anyway. Great Neck is Great Neck even when the Fitzgeralds are elsewhere. He told me of a newcomer who'd made money in the drug business—not dope but the regular line. This gentleman had evidently taken to Ring. One morning he called early with another man and a girl and Ring was not dressed. But he hurried down, unshaven. He was introduced to the girl only and he said he was sorry to appear that way but didn't want to keep them waiting while he shaved.

At this the drug man signals the other, who goes to the car for a black bag and from it produces razors, strops, etc., etc., and publicly shaves Ring. This was the drug man's private barber; the girl was his private manicurist. But as he was lonely he had made them also his companions. Ring declares this is true!

We're living in a quiet cottage near New Canaan. You would hate it but I like it. The nearest we've come to a party was a “beefsteak supper” on the Heyward Broun or Ruth Hale estate,*—an abandoned farm of 100 acres, a ruin of thickets, grass-grown roads, broken walls and decaying orchards. About the only person I knew there, really, among a rather Semitic-looking crowd, was snakey little Johnny Weaver,^ — and that didn't help much. But I had a swim in the lake with Heyward and a man whose name I've forgot. Ruth Hale led me instantly to the punch and filled me a cup because, she said, “I long to see an Evarts** drunk”;—and she added, “I loathe all Evartses”:—she knew some, for her brother, who died—and I liked him much—married a cousin of mine; and during his long, terrible illness there was war between the families as to his care, and I don't know which acted the more crazily. But the Evartses in general are rigorous for duty, the rights of property, the established church, the Republican Party, etc. I suppose that's what sets her against them.

Your standing with the public was never better. I'm always hearing people tell the ideas of your new stories. The novel, if it comes soon, will come at a good time. How will Hovey's leaving Hearst affect serialization? But I'm afraid you'll have to serialize.

My regards to Zelda.

Yours,

Notes:

* Columnist-critic Heywood Broun and reviewer-critic Ruth Hale were married from 1917 to 1933.

^ John V. A. Weaver, American critic, poet and playwright.

** Evarts was Perkins' mother's family name.

28. Between 1917 and 1923, Lardner had published eight books with Bobbs-Merrill (Gullible's Travels, etc.; My Four Weeks in France; Treat 'em Rough; Own Your Own Home; The Real Dope; The Young Immigrunts; Symptoms of Being 35; and The Big Town) and two (Say It With Oil and You Know Me Al) with George H. Doran.

108. TO: Maxwell Perkins

After 8 August 1924

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Villa Marie Valescure, St Raphael France.

Dear Max:

Thanks for your long + most interesting letter. I wrote you yesterday so this is just a note. I feel like saying “I told you so” about the Bobbs-Merril + Doran books of Rings but I know that it is mostly Bobbs-Merrils fault and a good deal Ring's.1 The ad was great—especially the Barrie. I imagine that Mr. Scribner was pleased—and a little surprised. Poor Ring—its discouraging that he keeps on drinking—how bored with life the man must be. I certainly think his collection for 1925 should include all fantasies. Certain marvellous syndicate articles such as the “fur coat + the worlds series” + the “celebrities day-book” should be saved for the “My Life and Loves” volume.2 Do read Seldes on Ring in “The Seven Lively Arts.” Be sure to. I'll really pay you to do it before making the selections.3

As Ever Scott

Notes:

1 Scribners had recently published Ring Lardner's How to Write Short Stories at Fitzgerald's urging, and was negotiating for the Lardner volumes previously published by Bobbs-Merrill and Doran.

2 What of It? (Scribners, 1925).

3 See Perkins' 8 August 1924 letter to Fitzgerald in Scott/Max.

109. To Perkins

Villa Marie, Valescure St. Raphael, France

[ca. August 25, 1924]

Dear Max:

1. The novel will be done next week. That doesn't mean however that it'll reach America before October 1st. as Zelda and I are contemplating a careful revision after a weeks complete rest.

2 The clippings have never arrived.

3. Seldes* has been with me and he thinks “For the Grimalkins” is a wonderful title for Rings book. Also I've got great ideas about “My Life and Loves” which I'll tell Ring when he comes over in September.

4 How many copies has his short stories sold?

5 Your bookkeeper never did send me my royalty report for Aug 1st.

6 For Christs sake don't give anyone that jacket you're saving for me. I've written it into the book.^

7 I think my novel is about the best American novel ever written. It is rough stuff in places, runs only to about 50,000 words & I hope you won't shy at it

8 Its been a fair summer. I've been unhappy but my work hasn't suffered from it. I am grown at last.

9. What books are being talked about. I don't mean bestsellers. Hergeshiemers novel in the Post** seems vile to me.

10. I hope you're reading Gertrude Steins novel in the Transatlantic Review.

11 Raymond Radiguets best book (he is the young man who wrote “Le diable au Corps” at sixteen [untranslatable]++) is a great hit here. He wrote it at 18. Its called “Le Bal de Compte Orgel” & though I'm only half through it I'd get an opinion on it if I were you. Its cosmopolitan rather than French and my instinct tells me that in a good translation it might make an enormous hit in America where everyone is yearning for Paris. Do look it up & get at least one opinion of it. The preface is by the da-dist Jean Cocteau but the book is not da-da at all.

12. Did you get hold of Rings other books?

13. We're liable to leave here by Oct 1st so after the 15th of Sept I wish you'd send everything care of Guarantee Trust Co. Paris

14 Please ask the bookstore, if you have time, to send me Havelock Ellis' “Dance of Life” & charge to my account.

15. I asked Struthers Burt to dinner but his baby was sick.

16 Be sure & and answer every question, Max. I miss seeing you like the devil.

Notes:

* Gilbert Seldes, American journalist and critic.

^ The dust jacket referred to showed two enormous eyes, supposedly those of Daisy Fay, brooding over New York City. This picture inspired the image of the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg in The Great Gatsby.

** Balisand.

^^ These brackets are Fitzgerald's.

Also Turnbull.

110. To Fitzgerald

September 10, 1924

Dear Scott:

I would have written you sooner, but if you had ever had hay-fever you would forgive me for waiting a couple of weeks until the “storm” of pollen had somewhat abated. It was worse than usual because our landlady thought she would make profit for her garden by the fact that there were strangers on the premises, with a crop of buckwheat. I knew buckwheat by reputation, but not by appearance, and so it was some time before I found out what was the matter.

…

…

As to the questions you asked:—The Ring Lardner clippings must have reached you some time ago.

I read a great part of Seldes' book* and got a great deal of fun out of it and considerable illumination. I got it to read the Ring Lardner especially and showed that part of it to Mr. Scribner.

We have sold about 12,000 copies of “How to Write Short Stories”. We have printed 15,000.

There is certainly not the slightest risk of our giving that jacket to anyone in the world but you. I wish the manuscript of the book would come, and I don't doubt it is something very like the best American novel. I found other people that were greatly impressed by your story in the Mercury—a very promising young writer in Philadelphia whom I went over to see, spoke of it without any introduction of the subject from me;—he said he had always looked upon you as a leader, had been at times a little bewildered, and had in this story felt a kind of renewal and advance.

As to the literature talked of,—“The American Mercury” is read by everybody and provokes a large part of the conversation. “So Big” by Edna Ferber is the most popular book, and one of the best. For some reason a good many people are reading a cheap affair by that bucolic sophisticate, Van Vechten, called “The tattooed Countess”. It is clever, but cheap and thin. The somewhat conservative and substantial book readers talk a great deal about a book by E. M. Fo[r]ster called “The Passage to India”, but I have only read about a third of it. “These Charming People”* is very popular among people you would be likely to see here, and word has come to those who have been on the other side, about another novel of his called, “The Green Hat”.

I have got Raymond Radeguet's book and am having it read. I am sending you “The Dance of Life” but personally I was very much disappointed in it because it fulfilled for me none of the expectations aroused by the opening statement of what the author proposed to do. Read individually all the essays are effective, but as a whole it fell down,—or else I did in reading it. All I have been able to get is one number of the Transatlantic Review, which did have one chapter of Gertrude Stein, and that Mr. Scribner^

Notes:

* Probably The Seven Lively Arts (1924).

* A novel by Michael Arlen.

^ The letter breaks off here, unsigned.

111. TO: Maxwell Perkins

Sept 10th 1924

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Villa Marie, Valescure St Raphael, France

Dear Max:

I am in rather a predicament. Mr. + Mrs. Gordan Sarre (Ruth Shepley) have my house, as you know, until the 1st day of October— that is for twenty days after the date heading this letter. Now we left in the house for purposes of subletting.

1 Blue figured dinning room rug

1 Stair carpet

and since I want the former I think its advisable to get it out by Oct 1st— otherwise Mrs. Miller may claim its hers, a way landladys have.

As Ring has gone and my others friends there are drunk and unreliable I'm going to ask you to send the enclosed to some reliable New York warehouse and ask them to call for the rugs and store them on Oct 1st.

I have left the name of the warehouse blank as I don't know one—thats why I'm asking you to pick one out + send it to them. I'm sure they do that sort of thing. This is a hell of a thing to ask anybody but I don't know what else to do as everybody in Great Neck is either incapable or crooked. I'm writing the tenants to deliver the property in question. God almighty! If I only knew a warehouse I could do it myself, but I don't.

Tom's book arrived.1 I've only read 40 pages but so far its remarkably interesting. The writing is curiously crude, almost Drieserian but I suppose that's deliberate.

Now for a promise—the novel will absolutely + definately be mailed to you before the 1st of October. I've had to rewrite practically half of it—at present its stored away for a week so I can take a last look at it + see what I've left out—there's some intangible sequence lacking somewhere in the middle + a break in interest there invariably means the failure of a book. It is like nothing I've ever read before.

As Ever Scott

Notes:

1 Thomas Boyd's The Dark Cloud.

112. To Perkins

Villa Marie, Valescure St. Raphael, France

[ca. October 10, 1924]

Dear Max:

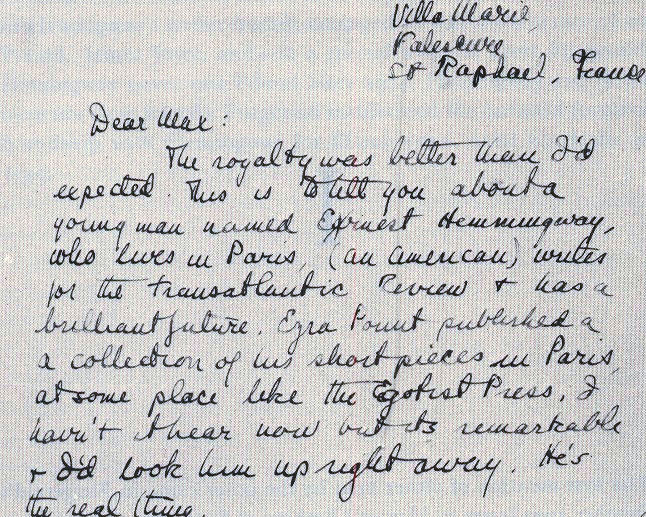

The royalty was better than I'd expected. This is to tell you about a young man named Ernest Hemmingway, who lives in Paris, (an American) writes for the transatlantic Review & has a brilliant future. Ezra Pount published a a collection of his short pieces in Paris, at some place like the Egotist Press.** I havn't it hear now but its remarkable & I'd look him up right away. He's the real thing.

My novel goes to you with a long letter within five days. Ring arrives in a week. This is just a hurried scrawl as I'm working like a dog. I thought Stalling's book^^ was disappointingly rotten. It takes a genius to whine appealingly. Have tried to see Struthers Burt but he's been on the move. More later.

P.S. Important. What chance has a smart young frenchman with an intimate knowledge of French literature in the bookselling business in New York. Is a clerk paid much and is there any opening for one specializing in French literature? Do tell me as there's a young friend of mine here just out of the army who is anxious to know.

Sincerely

Notes:

** Probably In Our Time, published by William Bird of Paris in the Spring of 1924. Ezra Pound helped Hemingway get the book published.

^^ Plumes by Laurence Stallings.

Also Turnbull.

113. To Fitzgerald

October 18, 1924

Dear Scott:

As a correspondent you are tantalizing: each letter makes me almost expect the manuscript of the novel before the next week and so that I count upon reading it then. Take your time;—but when it does come I hope it will be at the end of a week so that I won't be continually interrupted in reading it. Today I could do nothing on account of callers: Ellsworth Huntington, geographer and anthropologist for whom we have just published a book*—he promised us an article I suggested for Scribner's; then Ernest Boyd, most amusing, who said he was somewhat apprehensive of your 'reaction' to his chapter on you in a book Doran is issuing^—we are to publish “Studies in Nine Literatures” for him in the spring; then VanWyck Brooks, who is now investigating Emerson; then Burton Rascoe** whom I introduced to Mr. Brownell;++—and they chatted amicably for some time. And there were others too.

I think I shall soon have got something by Ernest Hemmingway though probably from abroad. Thanks for the tip. I am reading the Gertrude Stein as it comes out, and it fascinates me. But I doubt if the reader who had no literary interest, or not much, would have patience with her method, effective as it does become. Its peculiarities are much more marked than in “The Three Lives”. As for “Plumes”, I greatly liked those few pages about the earlier Plumes. I thought them remarkable in swift presentation and characterization; but I couldn't go the rest. His play, “What Price Glory” is a wonder everyone says. I must manage to see it.

The Lardners are I suppose with you. I wrote Ring we had acquired all the books and when he comes back I'll discuss the composition of a set. I hope he has talked it over with you. I enclose a string of ads. we are consistently running. “The Golden Honeymoon” one is, of course, out of key, altogether;—but the chief idea is to catch the eye and hold it a minute. Everyone thinks we have advertised the book well,—perhaps because, liking it, they have noticed the ads.

I told you we'd bought a house in New Canaan. It has the face of a Greek temple and the body of a spacious Connecticut farm house. It's recovering from a devastating raid of plumbers, carpenters, painters, roofers. I thought at one time it never would. We had always meant to leave Plainfield—a damnable flat, damp, dull, cheap place. This is better in almost every respect,—not worse in any. Eleanor Wylie* lives here;—but I have not yet seen that face that launched the souls of three men into eternity. Someone who had, said he could understand about the two husbands but he didn't see why the other man should have committed suicide.—But Louise^ thinks her charming and she must certainly be interesting. Tonight we dine at one Gregory Mason's about whom I only know from having declined two of his novels. I think he's chiefly a newspaper correspondent.

Mr. Scribner always asks about you. We all miss your calls—that's a fact.

I'm sending a good book—Sidney Howard's first.**

Yours,

Notes:

* The Character of Races as Influenced by Physical Environment, Natural Selection, and Historical Development.

^ Portraits: Real and Imaginary (1924).

** American journalist, reviewer and dramatic critic.

^^ William Crary Brownell, writer and critic and senior editor at Scribners.

* Elinor Wylie, American poetess and novelist.

^ Mrs. Maxwell E. Perkins.

** Three Flights Up, a collection of short fiction, published by Scribners in 1924.

114. To Perkins

October 27th, 1924

Villa Marie, Valescure St. Raphael, France (After Nov. 3d care of American Express Co., Rome Italy)

Dear Max:

Under separate cover I'm sending you my third novel:

The Great Gatsby

(I think that at last I've done something really my own), but how good “my own” is remains to be seen.

I should suggest the following contract.

15% up to 50,000

20% after 50,000

The book is only a little over fifty thousand words long but I believe, as you know, that Whitney Darrow** has the wrong psychology about prices (and about what class constitute the bookbuying public now that the lowbrows go to the movies) and I'm anxious to charge two dollars for it and have it a full size book.

Of course I want the binding to be absolutely uniform with my other books—the stamping too—and the jacket we discussed before. This time I don't want any signed blurbs on the jacket—not Mencken's or Lewis' or Howard's*** or anyone's. I'm tired of being the author of This Side of Paradise and I want to start over.

About serialization. I am bound under contract to show it to Hearsts but I am asking a prohibitive price, Long* hates me and its not a very serialized book. If they should take it—they won't—it would put of [f] publication in the fall. Otherwise you can publish it in the spring. When Hearst turns it down I'm going to offer it to Liberty for $15,000 on condition that they'll publish it in ten weekly installments before April 15th. If they don't want it I shan't serialize. I am absolutely positive Long won't want it.

I have an alternative title:

Gold-hatted Gatsby

After you've read the book let me know what you think about the title. Naturally I won't get a nights sleep until I hear from you but do tell me the absolute truth, your first impression of the book & tell me anything that bothers you in it.

As Ever

I'd rather you wouldn't call Reynolds as he might try to act as my agent. Would you send me the N.Y. World with accounts of Harvard-Princeton and Yale-Princeton games?

Notes:

* Ray Long, editor of Hearst's International.

** Sales manager at Scribners.

*** Playwright Sidney Howard.

Also Turnbull.

115. To Perkins

Hotel Continental St. Raphael, France (Leaving Tuesday)

[ca. November 7, 1924]

Dear Max:

By now you've recieved the novel. There are things in it I'm not satisfied with in the middle of the book—Chapters 6&7. And I may write in a complete new scene in proof. I hope you got my telegram.29 I have now decided to stick to the title I put on the book.

Trimalchio in West Egg

The only other titles that seem to fit it are Trimalchio and On the Road to West Egg. I had two others Gold-hatted Gatsby and The High-bouncing Lover but they seemed too light.

We leave for Rome as soon as I finish the short story I'm working on.

As Ever

I was interested that you've moved to New Canaan. It sounds wonderful. Sometimes I'm awfully anxious to be home.

But I am confused at what you say about Gertrude Stien. I thought it was one purpose of critics & publishers to educate the public up to original work. The first people who risked Conrad certainly didn't do it as a commercial venture. Did the evolution of startling work into accepted work cease twenty years ago?

Do send me Boyd's (Ernest's) book when it comes out. I think the Lardner ads are wonderful. Did the Dark Cloud flop?

Would you ask the people downstairs to keep sending me my monthly bill for the encyclopedia?

Notes:

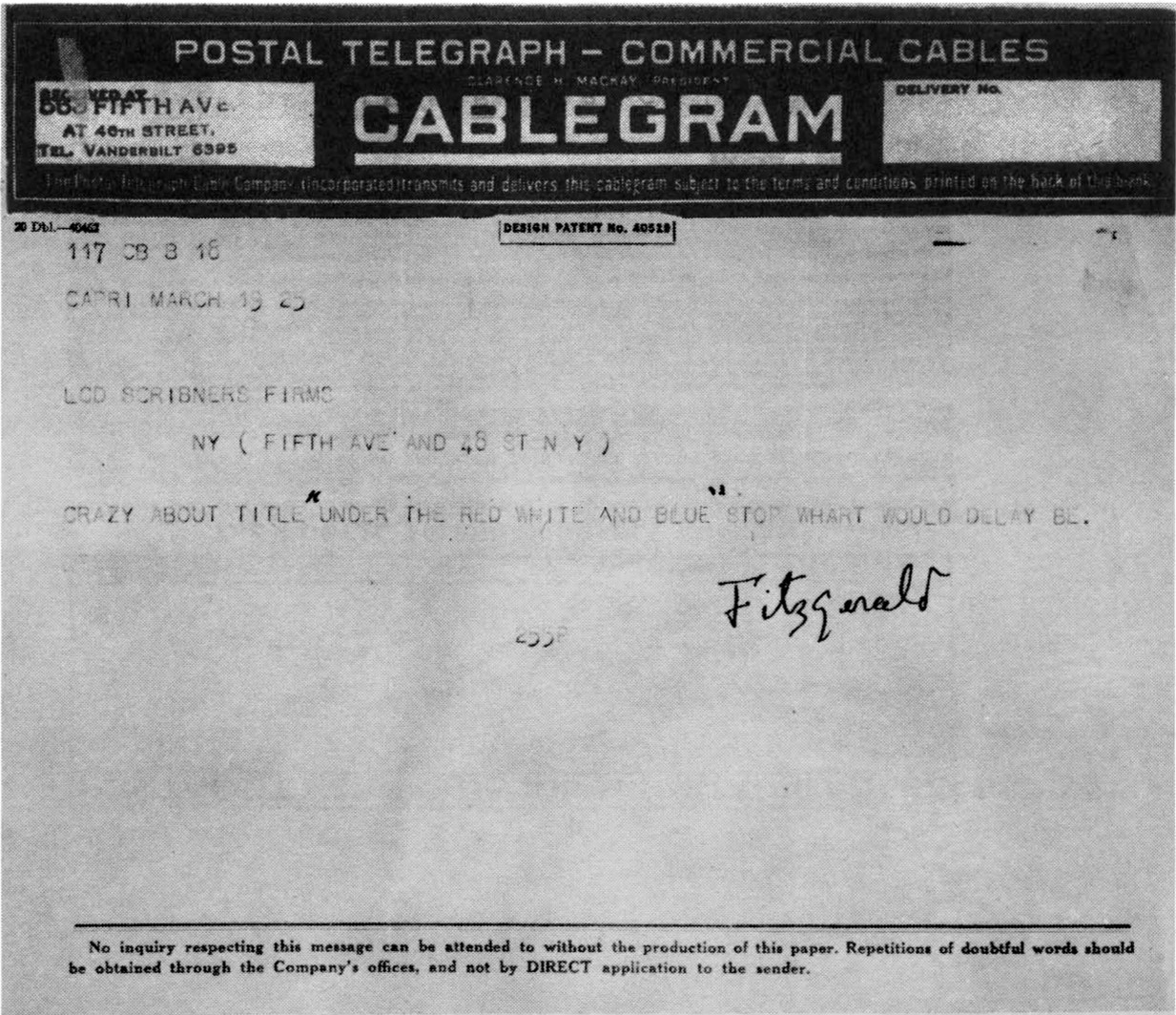

29. On October 28th, Perkins had wired, asking when he could expect the novel. On the same day, Fitzgerald replied, also by telegram, that he had sent it but was undecided about the title.

Also Turnbull.

116. To Perkins

Nov. 14, 1924

Dear Scott:

I think the novel is a wonder. I'm taking it home to read again and shall then write my impressions in full;—but it has vitality to an extraordinary degree, and glamour, and a great deal of underlying thought of unusual quality. It has a kind of mystic atmosphere at times that you infused into parts of “Paradise” and have not since used. It is a marvelous fusion, into a unity of presentation, of the extraordinary incongruities of life today. And as for sheer writing, it's astonishing.

Now deal with this question: various gentlemen here don't like the title,—in fact none like it but me. To me, the strange incongruity of the words in it sound the note of the book. But the objectors are more practical men than I. Consider as quickly as you can the question of a change.

But if you do not change, you will have to leave that note off the wrap. Its presence would injure it too much;—and good as the wrap always seemed, it now seems a masterpiece for this book. So judge of the value of the title when it stands alone and write or cable your decision the instant you can.

With congratulations, I am,

Yours,

117. To Fitzgerald

November 20, 1924

Dear Scott:

I think you have every kind of right to be proud of this book. It is an extraordinary book, suggestive of all sorts of thoughts and moods. You adopted exactly the right method of telling it, that of employing a narrator who is more of a spectator than an actor: this puts the reader upon a point of observation on a higher level than that on which the characters stand and at a distance that gives perspective. In no other way could your irony have been so immensely effective, nor the reader have been enabled so strongly to feel at times the strangeness of human circumstance in a vast heedless universe. In the eyes of Dr. Eckleberg various readers will see different significances; but their presence gives a superb touch to the whole thing: great unblinking eyes, expressionless, looking down upon the human scene. It's magnificent!

I could go on praising the book and speculating on its various elements, and meanings, but points of criticism are more important now. I think you are right in feeling a certain slight sagging in chapters six and seven, and I don't know how to suggest a remedy. I hardly doubt that you will find one and I am only writing to say that I think it does need something to hold up here to the pace set, and ensuing. I have only two actual criticisms: -

One is that among a set of characters marvelously palpable and vital—I would know Tom Buchanan if I met him on the street and would avoid him—Gatsby is somewhat vague. The reader's eyes can never quite focus upon him, his outlines are dim. Now everything about Gatsby is more or less a mystery i.e. more or less vague, and this may be somewhat of an artistic intention, but I think it is mistaken. Couldn't he be physically described as distinctly as the others, and couldn't you add one or two characteristics like the use of that phrase “old sport”,—not verbal, but physical ones, perhaps. I think that for some reason or other a reader—this was true of Mr. Scribner and of Louise—gets an idea that Gatsby is a much older man than he is, although you have the writer say that he is little older than himself. But this would be avoided if on his first appearance he was seen as vividly as Daisy and Tom are, for instance;—and I do not think your scheme would be impaired if you made him so.

The other point is also about Gatsby: his career must remain mysterious, of course. But in the end you make it pretty clear that his wealth came through his connection with Wolfsheim. You also suggest this much earlier. Now almost all readers numerically are going to be puzzled by his having all this wealth and are going to feel entitled to an explanation. To give a distinct and definite one would be, of course, utterly absurd. It did occur to me though, that you might here and there interpolate some phrases, and possibly incidents, little touches of various kinds, that would suggest that he was in some active way mysteriously engaged. You do have him called on the telephone, but couldn't he be seen once or twice consulting at his parties with people of some sort of mysterious significance, from the political, the gambling, the sporting world, or whatever it may be. I know I am floundering, but that fact may help you to see what I mean. The total lack of an explanation through so large a part of the story does seem to me a defect;—or not of an explanation, but of the suggestion of an explanation. I wish you were here so I could talk about it to you for then I know I could at least make you understand what I mean. What Gatsby did ought never to be definitely imparted, even if it could be. Whether he was an innocent tool in the hands of somebody else, or to what degree he was this, ought not to be explained. But if some sort of business activity of his were simply adumbrated, it would lend further probability to that part of the story.

There is one other point: in giving deliberately Gatsby's biography when he gives it to the narrator you do depart from the method of the narrative in some degree, for otherwise almost everything is told, and beautifully told, in the regular flow of it,—in the succession of events or in accompaniment with them. But you can't avoid the biography altogether. I thought you might find ways to let the truth of some of his claims like “Oxford” and his army career come out bit by bit in the course of actual narrative. I mention the point anyway for consideration in this interval before I send the proofs.

The general brilliant quality of the book makes me ashamed to make even these criticisms. The amount of meaning you get into a sentence, the dimensions and intensity of the impression you make a paragraph carry, are most extraordinary. The manuscript is full of phrases which make a scene blaze with life. If one enjoyed a rapid railroad journey I would compare the number and vividness of pictures your living words suggest, to the living scenes disclosed in that way. It seems in reading a much shorter book than it is, but it carries the mind through a series of experiences that one would think would require a book of three times its length.

The presentation of Tom, his place, Daisy and Jordan, and the unfolding of their characters is unequalled so far as I know. The description of the valley of ashes adjacent to the lovely country, the conversation and the action in Myrtle's apartment, the marvelous catalogue of those who came to Gatsby's house,—these are such things as make a man famous. And all these things, the whole pathetic episode, you have given a place in time and space, for with the help of T. J. Eckleberg and by an occasional glance at the sky, or the sea, or the city, you have imparted a sort of sense of eternity. You once told me you were not a natural writer—my God! You have plainly mastered the craft, of course; but you needed far more than craftsmanship for this.

As ever,

P.S. Why do you ask for a lower royalty on this than you had on the last book where it changed from 15% to 17 l/2 % after 20,000 and to 20% after 40,000? Did you do it in order to give us a better margin for advertising? We shall advertise very energetically anyhow and if you stick to the old terms you will sooner overcome the advance. Naturally we should like the ones you suggest better, but there is no reason you should get less on this than you did on the other.

118. To Perkins

Hotel des Princes Piazza di Spagna Rome, Italy

[ca. December 1, 1924]

Dear Max:

Your wire & your letters made me feel like a million dollars—I'm sorry I could make no better response than a telegram whining for money. But the long siege of the novel winded me a little & I've been slow on starting the stories on which I must live.

I think all your criticisms are true

(a) About the title. I'll try my best but I don't know what I can do. Maybe simply “Trimalchio” or “Gatsby.” In the former case I don't see why the note shouldn't go on the back.

(b) Chapters VI & VII I know how to fix

(c) Gatsby's business affairs I can fix. I get your point about them.

(d) His vagueness I can repair by making more pointed—this doesn't sound good but wait and see. It'll make him clear

(e) But his long narrative in Chap VIII will be difficult to split up. Zelda also thought I was a little out of key but it is good writing and I don't think I could bear to sacrifice any of it

(f) I have 1000 minor corrections which I will make on the proof & several more large ones which you didn't mention.

Your criticisms were excellent & most helpful & you picked out all my favorite spots in the book to praise as high spots. Except you didn't mention my favorite of all—the chapter where Gatsby & Daisy meet.

Two more things. Zelda's been reading me the cowboy book* aloud to spare my mind & I love it—tho I think he learned the American language from Ring rather than from his own ear.

Another point—in Chap. II of my book when Tom & Myrt[l]e go into the bedroom while Carraway reads Simon called Peter- is that raw? Let me know. I think its pretty nessessary.

I made the royalty smaller because I wanted to make up for all the money you've advanced these two years by letting it pay a sort of interest on it. But I see by calculating I made it too small—a difference of 2000 dollars. Let us call it 15% up to 40,000 and 20% after that. That's a good fair contract all around.

By now you have heard from a smart young french woman* who wants to translate the book. She's equeal to it intellectually & linguisticly I think—had read all my others—If you'll tell her how to go about it as to royalty demands ect.

Anyhow thanks & thanks & thanks for your letters. I'd rather have you & Bunny^ like it than anyone I know. And I'd rather have you like it than Bunny. If its as good as you say, when I finish with the proof it'll be perfect.

Remember, by the way, to put by some cloth for the cover uniform with my other books.

As soon as I can think about the title I'll write or wire a decision. Thank Louise** for me, for liking it. Best Regards to Mr. Scribner. Tell him Galsworthy is here in Rome.

As Ever,

Notes:

* Cowboys North and South by Will James.

* Irene de Morsier.

^ Edmund Wilson.

** Mrs. Maxwell Perkins

Also Turnbull.

119. To Fitzgerald

Dec. 16, 1924

Dear Scott:

Your cable changing the title to “The Great Gatsby” has come and has been followed; and as I just now cabled, we have deposited the seven hundred and fifteen [fifty].**

…

…

Ring came in at last and told me about being with you and Zelda, and then I got for the purposes of his book^^ the proofs of his articles about the trip which are to appear in Liberty;—and you and Zelda figure therein. “Mr. Fitzgerald,” he says, “is a novelist, and Mrs. Fitzgerald is a novelty.” And he tells how you got to Monte Carlo with nothing but a full dress coat. His articles are most excellent and I think we shall get a very good book out of all the material we have.

I wish you would see Struthers Burt. You would probably think he was extremely prejudiced in some respects, but he has a very interesting mind. He has a theory on almost every topic that comes up and whether valid or not, all his theories are intricate and interesting.

I hope you are thinking over “The Great Gatsby” in this interval and will add to it freely. The most important point I think, is that of how he comes by his wealth,—some sort of suggestion about it. He was supposed to be a bootlegger, wasn't he, at least in part, and I should think a little touch here and there would give the reader the suspicion that this was so and that is all that is needed.

Zelda wrote me a splendid letter from Rome in return for “The White Monkey”;*—that, by the way, has sold about 75,000 copies, although it came out very late. Tom's book^ has only sold about 3,000 but I really did not think it could do much more in view of its nature. I do think it a very interesting book which, though crudely, shows a great deal of power. We are publishing his stories in the spring.

I lunched the other day with John Biggs and the girl he is engaged to, a very feminine, wide awake, Wilmington girl. They must be going to be married pretty soon because they have bought a house which they are repairing,—that is, if he has any money left. I haven't.

As ever,

Notes:

“ The request for $750 and the title change were contained in a cable dated December 15th.

^^ What of It?, published in 1925.

* By John Galsworthy.

+ Through the Wheat by Thomas A. Boyd.

120. To Fitzgerald

Dec. 19, 1924

Dear Scott:

When Ring Lardner came in the other day I told him about your novel and he instantly balked at the title. “No one could pronounce it,” he said;—so probably your change is wise on other than typographical counts. Certainly it is a good title. I've just put in hand the material for a book by Ring and the first of it is an account of his European trip. Ober,** from whom you will have heard, called up this morning to say Liberty had decided not to take “The Great Gatsby” though Rex Lardner wanted to, because it was really above their readers and they did not want to run two serials at once. So we shall go ahead full speed;—and will you read the proof rapidly?

Not long ago I had a call from John Peale Bishop,++ who must get himself a job. He said nothing of his novel, nor did I. He looked, to me, quite a bit older than before he went abroad,—more than two years older;—said he and she were living in a roof house,—a little four room ediface, which sounded most attractive to me; but he did not regard it so poetically. He told of seeing you in Paris at a late hour in the early summer. By the way, I've only just now got word that something by that Hemingway you told me of is in a case at the custom's house,—a case of books. Did you ever look at that Will James book—not that I want you to: I'd rather you'd write than read.—But I have an idea that he could write a fine story—a sort of cowboy's Odyssey about a cattle drive or some such episode;—that with the barest tale to tell he would gain a continuity of interest that would greatly enhance the attraction of his writing. It would give him a show. I've proposed it to him. To be illustrated, of course, by him.

Here we are in our house since a week ago, and last night the new kitchen ceiling fell down. Now what the hell! And the men who put it up don't even seem surprised. They're perfectly willing to put up another though at twelve dollars a day per man. They're a great bunch, these members of what Ring Lardner might laughingly call the “laboring class”. But the house suits us anyway.

Yours as ever,

Notes:

** Literary agent Harold Ober, an associate at this time of Paul Reynolds. Ober was gradually taking over from Reynolds the placing of Fitzgerald's work.

^^ American poet and novelist who had attended Princeton with Fitzgerald.

121. To Perkins

Hotel des Princes Piazza di Spagna Rome, Italy

[ca. December 20, 1924]

Dear Max:

I'm a bit (not very—not dangerously) stewed tonight & I'll probably write you a long letter. We're living in a small, unfashionable but most comfortable hotel at $525.00 a month including tips, meals ect. Rome does not particularly interest me but its a big year here, and early in the spring we're going to Paris. There's no use telling you my plans because they're usually just about as unsuccessful as to work as a religious prognosticaters are as to the End of the World. I've got a new novel to write—title and all, that'll take about a year. Meanwhile, I don't want to start it until this is out & meanwhile I'll do short stories for money (I now get $2000.00 a story but I hate worse than hell to do them) and there's the never dying lure of another play.

Now! Thanks enormously for making up the $5000.00* I know I don't technically deserve it considering I've had $3000.00 or $4000.00 for as long as I can remember. But since you force it on me (inexecrable [or is it execrable] joke) I will accept it. I hope to Christ you get 10 times it back on Gatsby—and I think perhaps you will.

For:

I can now make it perfect but the proof (I will soon get the immemorial letter with the statement “We now have the book in hand and will soon begin to send you proof” [what is 'in hand'—I have a vague picture of everyone in the office holding the book in the light and and reading it]+) will be one of the most expensive affairs since Madame Bovary. Please charge it to my account. If its possible to send a second proof over here I'd love to have it. Count on 12 days each way—four days here on first proof & two on the second. I hope there are other good books in the spring because I think now the public interest in books per se rises when there seems to be a group of them as in 1920 (spring & fall), 1921 (fall), 1922 (spring). Ring's & Tom's* (first) books, Willa Cathers Lost Lady & in an inferior, cheap way Edna Ferber's are the only American fiction in over two years that had a really excellent press (say, since Babbit).

With the aid you've given me I can make “Gatsby” perfect. The chapter VII (the hotel scene) will never quite be up to mark—I've worried about it too long & I can't quite place Daisy's reaction. But I can improve it a lot. It isn't imaginative energy that's lacking- its because I'm automaticly prevented from thinking it out over again because I must get all those characters to New York in order to have the catastrophe on the road going back & I must have it pretty much that way. So there's no chance of bringing the freshness to it that a new free conception sometimes gives.

The rest is easy and I see my way so clear that I even see the mental quirks that queered it before. Strange to say my notion of Gatsby's vagueness was O.K. What you and Louise & Mr. Charles Scribner found wanting was that:

I myself didn't know what Gatsby looked like or was engaged in & you felt it. If I'd known & kept it from you you'd have been too impressed with my knowledge to protest. This is a complicated idea but I'm sure you'll understand. But I know now—and as a penalty for not having known first, in other words to make sure I'm going to tell more.

It seems of almost mystical significance to me that you thot he was older—the man I had in mind, half unconsciously, was older (a specific individual) and evidently, without so much as a definate word, I conveyed the fact.—or rather, I must qualify this Shaw-Desmond-trash by saying that I conveyed it without a word that I can at present and for the life of me, trace. (I think Shaw Desmond^ was one of your bad bets—I was the other)

Anyhow after careful searching of the files (of a man's mind here) for the Fuller Magee case** & after having had Zelda draw pictures until her fingers ache I know Gatsby better than I know my own child. My first instinct after your letter was to let him go & have Tom Buchanan dominate the book (I suppose he's the best character I've ever done—I think he and the brother in “Salt” & Hurstwood in “Sister Carrie” are the three best characters in American fiction in the last twenty years, perhaps and perhaps not) but Gatsby sticks in my heart. I had him for awhile then lost him & now I know I have him again. I'm sorry Myrtle is better than Daisy. Jordan of course was a great idea (perhaps you know its Edith Cummings)* but she fades out. Its Chap VII thats the trouble with Daisy & it may hurt the book's popularity that its a man's book.

Anyhow I think (for the first time since The Vegetable failed) that I'm a wonderful writer & its your always wonderful letters that help me to go on believing in myself.

Now some practical, very important questions. Please answer every one.

1. Montenegro has an order called The Order of Danilo. Is there any possible way you could find out for me there what it would look like—whether a courtesy decoration given to an American would bear an English inscription—or anything to give versimilitude to the medal which sounds horribly amateurish.

2. Please have no blurbs of any kind on the jacket!!! No Mencken or Lewis or Sid Howard or anything. I don't believe in them one bit any more.

3. Don't forget to change name of book in list of works

4. Please shift exclamation point from end of 3d line to end of 4th line in title page poem. Please! Important!

5. I thought that the whole episode (2 paragraphs) about their playing the Jazz History of the world at Gatsby's first party was rotten. Did you? Tell me frank reaction—personal, don't think! We can all think!

Got a sweet letter from Sid Howard—rather touching. I wrote him first. I thought Transatlantic was great stuff—a really gorgeous surprise. Up to that I never believed in him 'specially & I was sorry because he did in me. Now I'm tickled silly to find he has power, and his own power. It seemed tragic too to see Mrs. Viectch wasted in a novelette when, despite Anderson the short story is at its lowest ebb as an art form. (Despite Ruth Suckow, Gertrude Stien, Ring there is a horrible impermanence on it because the overwhelming number of short stories are impermanent.

Poor Tom Boyd! His cycle sounded so sad to me—perhaps it'll be wonderful but it sounds to me like sloughing in a field whose first freshness has gone.

See that word?* The ambition of my life is to make that use of it correct. The temptation to use it as a neuter is one of the vile fevers in my still insecure prose.

Tell me about Ring! About Tom—is he poor? He seems to be counting on his short story book, frail cane! About Biggs***—did he ever finish the novel? About Peggy Boyd****. I think Louise might have sent us her book!

I thot the White Monkey was stinko. On second thoughts I didn't like Cowboys, West & South either. What about Bal de Compte Orget? and Ring's set? and his new book? & Gertrude Stien? and Hemmingway?

I still owe the store almost $700 on my Encyclopedia but I'll pay them on about Jan 10th—all in a lump as I expect my finances will then be on a firm footing. Will you ask them to send me Ernest Boyd's book*****? Unless it has about my drinking in it that would reach my family. However, I guess it'd worry me more if I hadn't seen it than if I had. If my book is a big success or a great failure (financial—no other sort can be imagined, I hope) I don't want to publish stories in the fall. If it goes between 25,000 and 50,000 I have an excellent collection for you. This is the longest letter I've written in three or four years. Please thank Mr. Scribner for me for his exceeding kindness.

Always yours

Notes:

^ These brackets are Fitzgerald's

* Thomas A. Boyd best known for his war novel, Through the Wheat.

^ Irish poet, dramatist and novelist.

** Edward M. Fuller and William F. McGee, partners in a brokerage firm, had been convicted, after four trials, of pocketing their customers' order money. Arnold Rothstein, the famous gambler and model for Meyer Wolfsheim in Gatsby, was the man behind Fuller and McGee. Fuller was Fitzgerald's neighbor in Great Neck.

* A famous woman golfer who once won the women's national championship. Fitzgerald had met her when she was a classmate at Westover School of Ginevra King, a girl he dated while he was at Princeton.

* Fitzgerald had circled “whose” in the previous sentence.

* The $750 as per Fitzgerald's telegram of December 15th made a total of $5000 advanced him on the publication of Gatsby.

*** Fitzgerald's college friend, John Biggs.

**** Mrs. Thomas Boyd.

***** Portraits Real and Imaginary

Also Turnbull.

122. To Perkins

Hotel des Princes Rome

[ca. January 15, 1925]

Dear Max:

Proof hasn't arrived yet. Have been in bed for a week with grippe but I'm ready to attack it violently. Here are two important things.

1. In [Is] the scene in Myrt[l]es appartment—in the place where Tom & Myrtle dissapear for awhile noticeably raw. Does it stick out enough so that the censor might get it. Its the only place in the book I'm in doubt about on that score. Please let me know right away.

2. Please have no quotations from any critics whatsoever on the jacket -simply your own blurb on the back and don't give away too much of the idea—especially don't connect Daisy & Gatsby (I need the quality of surprise there.) Please be very general.

These points are both very important. Do drop me a line about them. Wish I could see your new house. I havn't your faith in Will James—I feel its old material without too much feeling or too new a touch.

As Ever,

123. To Fitzgerald

Jan. 20, 1925

Dear Scott:

I am terribly rushed for time so I am answering your letter as briefly and rapidly as I can,—but I will have a chance to write to tell you the news, etc. etc., soon.

First as to the jazz history of the world:—that did jar on me unfavorably. And yet in a way it pleased me as a tour de force, but one not completely successful. Upon the whole, I should probably have objected to it in the first place except that I felt you needed something there in the way of incident, something special. But if you have something else, I would take it out.

You are beginning to get me worried about the scene in Myrtle's apartment for you have spoken of it several times. It never occurred to me to think there was any objection to it. I am sure there is none. No censor could make an issue on that,—nor I think on anything else in the book.

I will be sure not to use any quotations and I will make it very general indeed, because I realize that not much ought to be said about the story. I have not thought what to say, but we might say something very brief which gave the impression that nothing need any longer be said.

I certainly hope the proofs have got to you and that you have been at work on them for some time. If not you had better cable. They were sent first-class mail. The first lot on December 27th and the second lot on December 30th.

Yours,

P.S. The mysterious hand referred to in the immemorial phrase is that of the typesetter.

124. To Perkins

Hotel des Princes, Rome, Italy.

January 24th. = 1925

(But address the American Express Co. because its damn cold here and we may leave any day.

Dear Max:

This is a most important letter so I'm having it typed. Guard it as your life.

1) Under a separate cover I'm sending the first part of the proof. While I agreed with the general suggestions in your first letters I differ with you in others. I want Myrtle Wilson's breast ripped off- its exactly the thing, I think, and I don't want to chop up the good scenes by too much tinkering. When Wolfsheim says “sid” for “said”, it's deliberate. “Orgastic” is the adjective from “orgasm” and it expresses exactly the intended ecstasy. It's not a bit dirty. I'm much more worried about the disappearance of Tom and Myrtle on Galley 9—I think it's all right but I'm not sure. If it isn't please wire and I'll send correction.30

2) Now about the page proof—under certain conditions never mind sending them (unless, of course, there's loads of time, which I suppose there isn't. I'm keen for late March or early April publication)

The conditions are two.

a) That someone reads it very carefully twice to see that every one of my inserts are put in correctly. There are so many of them that I'm in terror of a mistake.

b) That no changes whatsoever are made in it except in the case of a misprint so glaring as to be certain, and that only by you.

If there's some time left but not enough for the double mail send them to me and I'll simply wire O.K. which will save two weeks. However don't postpone for that. In any case send me the page proof as usual just to see.

3) Now, many thanks for the deposit. Two days after wiring you I had a cable from Reynolds that he'd sold two stories of mine for a total of $3,750. but before that I was in debt to him and after turning down the ten thousand dollars from College Humor* I was afraid to borrow more from him until he'd made a sale. I won't ask for any more from you until the book has earned it. My guess is that it will sell about 80,000 copies but I may be wrong. Please thank Mr. Charles Scribner for me. I bet he thinks he's caught another John Fox** now for sure. Thank God for John Fox. It would have been awful to have had no predecessor

4) This is very important. Be sure not to give away any of my plot in the blurb. Don't give away that Gatsby dies or is a parvenu or a crook or anything. Its a part of the suspense of the book that all these things are in doubt until the end. You'll watch this won't you? And remember about having no quotations from critics on the jacket- not even about my other books!

5) This is just a list of small things.

a) What's Ring's title for his spring book?

b) Did O'Brien star my story “Absolution” or any of my others on his trash-album?***

c) I wish your bookkeeping department would send me an account on February first. Not that it gives me pleasure to see how much in debt I am but that I like to keep a yearly record of the sales of all my books.

Do answer every question and keep this letter until the proof comes. Let me know how you like the changes. I miss seeing you, Max, more than I can say.

As ever,

P. S. I'm returning the proof of the title page ect. It's O.K. but my heart tells me I should have named it Trimalchio. However against all the advice I suppose it would have been stupid and stubborn of me. Trimalchio in West Egg was only a compromise. Gatsby is too much like Babbit and The Great Gatsby is weak because there's no emphasis even ironically on his greatness or lack of it. However let it pass.

Notes:

* To serialize The Great Gatsby.

** A Scribner novelist who had written some runaway best sellers.

*** Best American Short Stories, collected annually by Edward J. O'Brien.

30. Early in February, Fitzgerald wrote, “I've thought it over & decided the Tom & Myrtle episode in Chap. HI isn't half as rough as lots of things in the B.&D. and should stand.”

Also Turnbull.

125. TO: Maxwell Perkins

Late January 1925

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Rome American Express Co.

Most important of all, I've thought it over + decided the Tom + Myrtle episode in Chap III isn't half as rough as lots of things in the B.+D. and should stand. Havn't heard from you on the subject but sure you agree

Dear Max:

Three things

(1.) The Plaza Hotel scene (Chap VII) is now wonderful and that makes the book wonderful. It should reach you in 3 days

(2) I hope you're sending Irene de Moirier1 the page proof and not the galley. Sure!

(3) Didn't you think I was heroic to turn down $10,000.2 God! I wish I'd been a month earlier with it.

No news. Proof should all reach you within 10 days after this letter

Scott.

Starved for news!!!

Notes:

1 Miss de Moirier was planning to translate The Great Gatsby into French, but dropped the project.

2 College Humor had offered $10,000 for serial rights to The Great Gatsby, which would have delayed publication.

126. To Perkins

new address Hotel Tiberio Capri

[ca. February 18, 1925]

Dear Max:

After six weeks of uninterrupted work the proof is finished and the last of it goes to you this afternoon. On the whole its been very successful labor

(1.) I've brought Gatsby to life

(2.) I've accounted for his money

(3.) I've fixed up the two weak chap[t]ers (VI and VII)

(4.) I've improved his first party

(5.) I've broken up his long narrative in Chap. VIII

This morning I wired you to hold up the galley of Chap 40. The correction—and God! its important because in my other revision I made Gatsby look too mean—is enclosed herewith. Also some corrections for the page proof.

We're moving to Capri. We hate Rome. I'm behind financially and have to write three short stories. Then I try another play, and by June, I hope, begin my new novel.

Had long interesting letters from Ring and John Bishop. Do tell me if all corrections have been recieved. I'm worried.

I hope you're setting publication date at first possible moment.

Notes:

Also Turnbull.

127. To Fitzgerald

Feb. 24, 1925

Dear Scott:

I congratulate you on resisting the $10,000. I don't see how you managed it. But it delighted us, for otherwise book publication would have been deferred until too late in the spring… Those [changes] you have made do wonders for Gatsby,—in making him visible and palpable. You're right about the danger of meddling with the high spots—instinct is the best guide there. I'll have the proofs read twice, once by Dunn and once by Roger,* and shall allow no change unless it is certain the printer has blundered. I know the whole book so well myself that I could hardly decide wrongly. But I won't decide anything if there is ground for doubt.

Ring Lardner came back last week from Nassau looking brown and well, with the page proof of his new book—“What of It”. I'll send you a copy soon. That and “How to Write Short Stories,” “Alibi Ike,” “The Big Town,” and “Gullible's Travels,” with new prefaces, constitute the set. I simply could not get Ring to pay enough attention to it to reorganize the material as we might have done. I tried to work out a book to contain “Symptoms of Being 35” and some of the shorter things; but without the war material—which, good as it was, seems dreadfully old now—there was not enough. And the subscription agents wanted to retain the familiar titles for their canvassing. “How to Write Short Stories” has sold 16,500 copies and it continues steadily to sell: the new book and the old books in new forms and wrappers, in the trade, will give it new impetus. We'll have a wonderful Ring Lardner window when we get all these books out.

As for Hemingway: I finally got his “In our time” which accumulates a fearful effect through a series of brief episodes, presented with economy, strength and vitality. A remarkable, tight, complete expression of the scene, in our time, as it looks to Hemingway. I have written him that we wish he would write us about his plans and if possible send a ms.; but I must say I have little hope that he will get the letter,—so hard was it for me to get his book. Do you know his address?

Here, the great recent piece of literary gossip arose from a luncheon to Sherwood Anderson given by his publisher Ben Heubsch. All the critics and commentators were guests, including Stuart P. Sherman^ and Mencken;—and Mencken refused to meet Sherman. Not point blank, but in such a way that all the room was aware; and the general tension was not reduced when, upon Anderson's refusal to speak, old Dutch Van Loon** arose and said perhaps a question he had long wanted to ask him might suggest a topic:—why did he let Ben Heubsch publish his books?—If it was a jest, and heaven knows how it was, there was too much truth in the implication. As for the other situation, Sherman has set upon Mencken with violence, in his articles, a number of times. But Mencken is not the man to resent that, even when, as once he did, I suppose to draw him out, Sherman charged him with cowardice. Apparently Mencken has detested Sherman on account of some anti-German-American articles he wrote during the war. I'm to see Sherman Wednesday and may hear more about it,—not that it matters.

There are here two couples we much enjoy seeing: the Benets* and the Colums. Molly Colum I think is a wonder, quick as a cat. And Padriac trails along an atmosphere of good nature and peaceful humor. Elinor Wylie is very much of a person, and Benet I like.—At all events, there was no one in Plainfield of this sort whatever. It was a bore there to go anywhere unless artificial stimulant was plentiful.

The other day I sent Tom Boyd a cheque of about $683 in royalties. “The Dark Cloud” is to be published by Fisher Unwin in England, which will help. We're publishing his stories under the title, “Points of Honor”,—not with the hope of much of a sale of course; but they will help him, and while I hardly took seriously his idea of a trilogy, I have hopes of the book he is now doing by itself, not because I know much of it but because I believe in him once he gets control of himself. Some of the best find that the hardest. I think he is utterly honest, and has strong, deep feeling, which is the great thing. He does not work hard over his writing—once it is down on paper it seems to bore him;—but this he realizes…

…

As ever,

Notes:

* Charles Dunn and Roger Burlingame, Scribners editors.

* American literary critic, then editor of the New York Herald Tribune Sunday Books section.

** Hendrik Willem Van Loon, Dutch-American historian, then Associate Editor of the Baltimore Sun.

* William Rose Benet, American poet, novelist and critic, was married to poetess Elinor Wylie from 1923 until her sudden and premature death in 1928.

128. TO: Maxwell Perkins

c. March 12, 1925

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University; Life In Letters.

Hotel Tiberio, Capri

Dear Max:

Thanks many times for your nice letter. You answered all questions (except about the account) I wired you on a chance about the title[31]—I wanted to change back to Gold-hatted Gatsby but I don’t suppose it would matter. That’s the one flaw in the book—I feel Trimalchio might have been best after all.

Don’t forget to send Ring’s book. Hemmingway could be reached, I’m sure, through the Transatlantic review. I’m going to look him up when we get to Paris. I think its amusing about Sherman and Mencken—however Sherman’s such a louse that it doesn’t matter. He wouldn’t have shaken Mencken’s hand during the war—he’s only been bullied into servility and all the Tribune appointments in the world wouldn’t make him more than 10th rate. Poor Sherwood Anderson. What a mess his life is—almost like Driesers. Are you going to do “Le Bal de Compte Orgel”—I think you’re losing a big opportunity if you dont. The success of The Little French Girl is a pointer of taste—and this is really French, and sensational and meritorious besides.

I hope you’re sending page proofs to that French woman who wants to translate Gatsby! I’m sending in two other envelopes.

(1.) Cards to go in books to go to critics

(2) " " " " " " " " friends

Also, I’m enclosing herewith a note I wish you’d send down to the retail dept.

They won’t forget to send copies to all the liberal papers—Freeman, Liberator, Transatlantic, Dial ect?

Can’t you send me

a jacket now?

Scott

While, on the contrary these 16 are all personal. Like wise I wish they’d tear off the adress and send each message in a book charged to my account.

For myself in Europe 6 books will be enough—one post haste and five at liesure.

Fitzg.

Notes:

In his February 24, 1925, letter Perkins had reported on a confrontation between New York Herald Tribune Books editor Stuart P. Sherman and H. L. Mencken.

Popular 1924 novel by Anne Douglas Sedgwick.

31. On March 7th, Fitzgerald had wired, “Is it too late to change title[?]” Perkins replied, also by cable, on March 9th, “Title change would cause bad delay and confusion.”

[Attachments:]

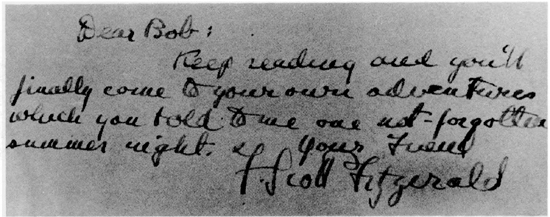

128a. TO: Robert Kerr

April 1925

Inscription pasted in The Great Gatsby.

Doris Kerr Brown

Capri, Italy

Dear Bob: Keep readingand you'll finally come to ...

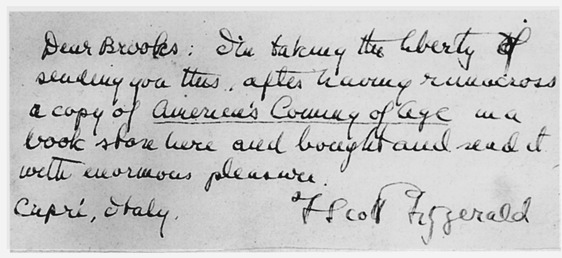

128b. TO: Van Wyck Brooks

April 1925

Inscription pasted in The Great Gatsby.

Bruccoli

Capri, Italy

Dear Brooks: I'm taking the liberty ...

Van Wyck Brooks - Literary historian and critic.

128c. TO: Sinclair Lewis

April 1925

Inscription pasted in The Great Gatsby.

University of Tulsa

Capri, Italy

Dear Sinclair Lewis: I've just sent for Arrowsmith. ...

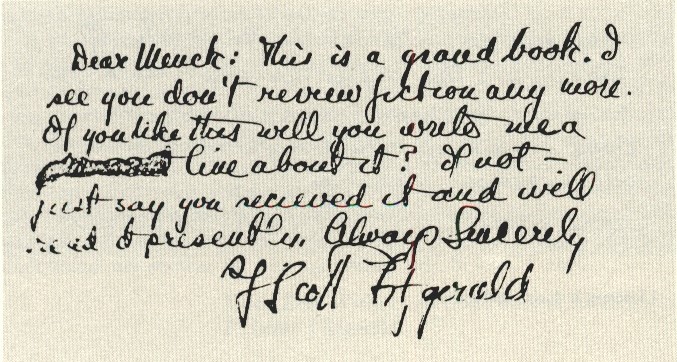

128d. TO: H. L. Mencken

April 1925

Inscription pasted in The Great Gatsby.

Enoch Pratt Free Library

Capri, Italy

Dear Menck: This is a grand book. ...

128e. TO: Mrs. Edward Fitzgerald

April 1925

Inscription pasted in The Great Gatsby. Auction

Capri, Italy

It's a masterpiece, Mother. Write me how you like it.

128f. Other presentation slips

April 1925

Lily Library, Indiana University

List of names:

Franklin P. Adams,

Herbert Agar,

Thomas Beer,

Prince Antoine Bibesco,

John Peale Bishop,

Ernest Boyd,

Thomas A. Boyd,

Heywood Broun,

James Branch Cabell,

Henry Siedel Canby,

Mary Coleman,

William Curtiss,

Benjamin de Casseris,

John Farrar,

Blair Flandran,

John Galesworthy,

Hildegarde Hawthorne,

Sidney Howard,

Robert McClure,

Cyril Maplethorpe,

Eunice Nathan,

George Jean Nathan,

Burton Rascoe,

Paul Rosenfeld,

Mrs. A.D. Sayre,

Gilbert Seldes,

Laurence Stallings,

Charles Hanson Towne,

Carl Van Doren,

Carl Van Vetchten,

Bernard Vaughn,

J.A.V. Weaver,

Edmund Wilson Jr.,

Alexander Wolcott

129. To Fitzgerald

March 19, 1925

Dear Scott:

This is not a letter, but a sort of bulletin. All the corrections came safely, I am sure, and all have been rightly made. I had to make two little changes: there are no tides in Lake Superior, as Rex Lardner told me and I have verified the fact, and this made it necessary to attribute the danger of the yacht to wind. The other change was where in describing the dead Gatsby in the swimming pool, you speak of the “leg of transept”. I ought to have caught this on the galleys. The transept is the cross formation in a church and surely you could not figuratively have referred to this. I think you must have been thinking of a transit, which is an engineer's instrument. It is really not like compasses, for it rests upon a tripod, but I think the use of the word transit would be psychologically correct in giving the impression of the circle being drawn. I think this must be what you meant, but anyway it could not have been transept. You will now have page proofs and you ought to deal with these two points and make them as you want them, and I will have them changed in the next printing. Otherwise we found only typographical errors of a perfectly obvious kind. I think the book is a wonder and Gatsby is now most appealing, effective and real, and yet altogether original. We publish on April 10th.32

I am awfully sorry that Zelda has been ill, and painfully. I hope it is all over now. Pain is regarded altogether too likely in this world. It is about the worst thing there is.

I am sending you a wonderful story by Ring Lardner in Liberty. We worked his “Young Immigrunts” and “Symptoms of Being 35” into the set.

As ever,

Notes:

32. Fitzgerald cabled, on March 19th, “Crazy about title 'Under the Red[,] White and Blue.' What would delay be[?]” Perkins cabled back, on the same day, “Advertised and sold for April tenth publication. Change suggested would mean some weeks delay, very great psychological damage. Think irony is far more effective under less leading title. Everyone likes present title. Urge we keep it.” On March 22nd, Fitzgerald, by telegram "YOURE RIGHT" agreed.

130. To Fitzgerald

March 25, 1925

Dear Scott:

I'm sending the French lady* a set of page proof,—the set that Ring had over the week end. He liked the book greatly—so he said yesterday when seated in my box stall before an artist who was sketching him—and is writing you about it. He said also that he expected to have enough stories for a fall book and if he does he will have a much greater success, I think, than with the first. He is now almost as healthy looking as on that night at your house in West Egg when he had not smoked or drunk for a long time.

Didn't I send you “The Apple of the Eye”?* I don't know why not: I was mightily impressed by it—by its Hardy like inevitability—I really don't know much about Hardy and don't think Tess had the quality, but I mean what he is supposed to stand for. With the help of Ernest Boyd I came in touch with the author and although many people loathe him—largely on account of a sort of lispy, preciosity—an Oxford accent -I was not unfavorably affected at all;—and I could have got his next book if I had found any support. I missed you greatly then. (This is strictly confidential.)