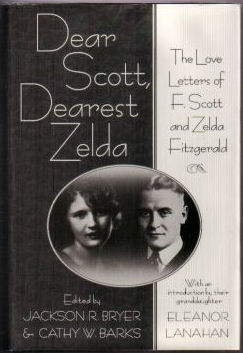

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda

Correspondence of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

A Small Foreword:

This collection includes all survived letters and telegrams from F. Scott Fitzgerald to Zelda (91),

also, all publushed letters from Zelda to Scott (252) plus some letters from Zelda to other persons;

Please note that 241 letters from Zelda to Scott (stored in Princetion archive) are still, as of Sept. 2024, unpublished.

Compiled by Anton Rudnev.

PART I

Courtship and Marriage: 1918–1920

1. TO ZELDA

[August 1918]

ALS, 1 p. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

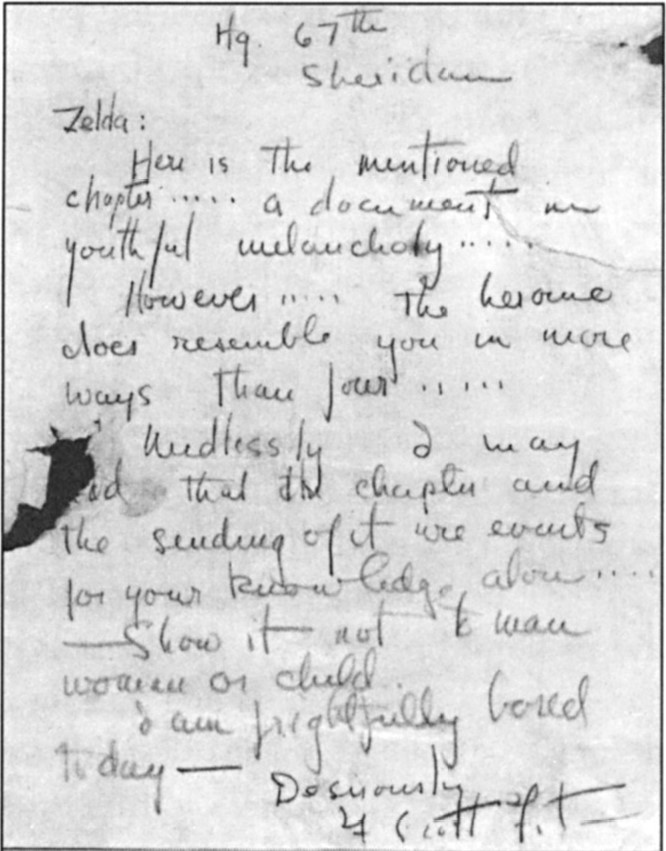

Hq. 67th

[Camp] Sheridan[, Montgomery, Alabama]

Zelda:

Here is the mentioned chapter … a document in youthful melancholy …

However … the heroine does resemble you in more ways than four …

Needlessly I may add that the chapter and the sending of it are events for your knowledge alone … —Show it not to man woman or child.

I am frightfully bored today—

Desirously

F. Scott Fit—

Notes:

1. Scott sent Zelda a chapter from his novel, “The Romantic Egotist,” the summer that they first met. Although Scribners returned Scott’s manuscript the same month (August 1918), Maxwell Perkins, who would become his editor, wrote Scott an encouraging letter, suggesting that he revise and resubmit the novel.

At the time Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre she was eighteen years old and a locally famous belle.

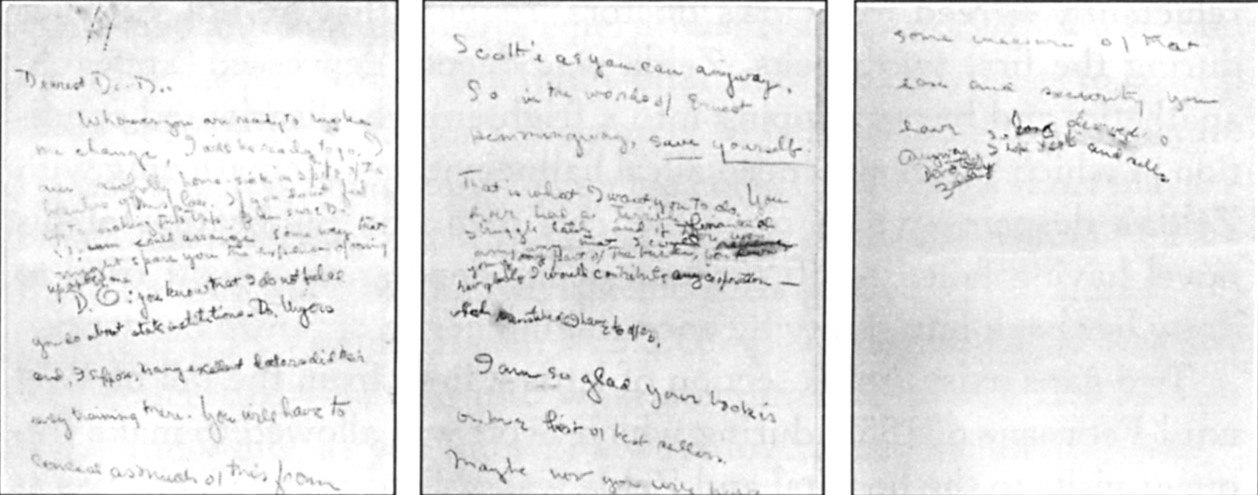

04 Facsimile of Scott’s August 1918 letter to Zelda. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

2. TO SCOTT

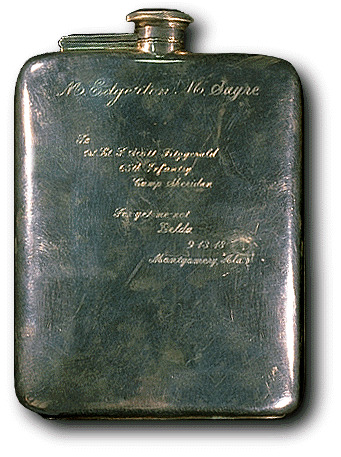

Flask, engraved

M. Edgerton M. Sayre

To

1st Lt. F. Scott Fitzgerald

65th Infantry

Camp Sheridan

Forget me not

Zelda

9.13.18

Montgomery, Ala.

The flask presented to Fitzgerald from Zelda.

3. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

CHARLOTTE NC 122 AM FEB 21ST 1919

MISS TELDA FAYRE

CARE FRANCES STUBBS

AUBURN ALA

YOU KNOW I DO NOT [DOUBT?] YOU DARLING

SCOTT

1103AM

Notes:

2. All wires in the book are reproduced as transmitted by the telegraph service. Misspellings, such as those in Zelda’s name here, have not been corrected.

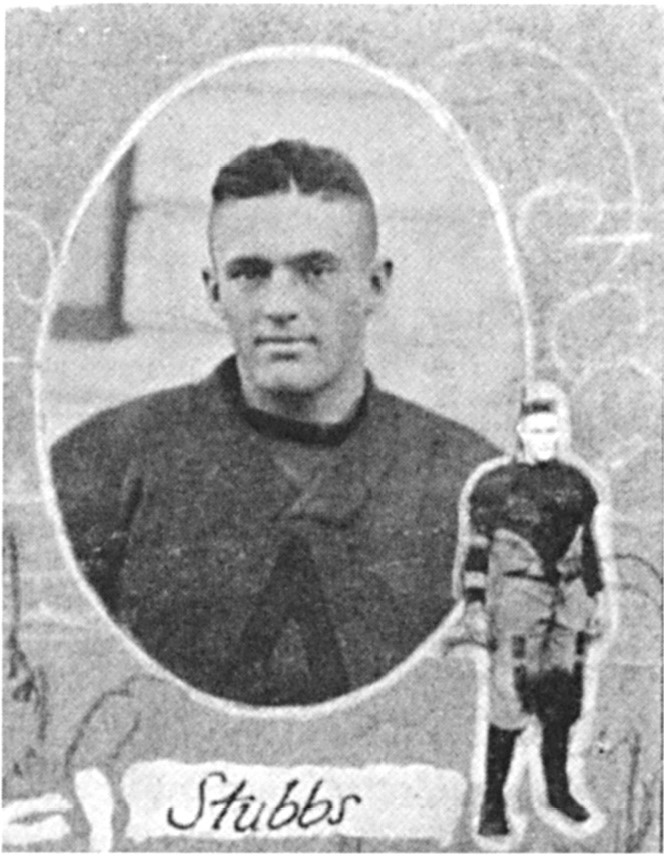

3. Francis Stubbs, with whom Zelda had a date, was one of Auburn University’s star football players. Scott, discharged from the military, was on his way to New York when he wired Zelda, who was at Auburn with Stubbs, perhaps hoping to ensure her fidelity by expressing trust in her.

Stubbs was Zelda's date at an Auburn party. Fitzgerald sent this wire from the train en route from Montgomery to New York following his army discharge.

Auburn football star Francis Stubbs; Zelda pasted this picture in her scrapbook. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

4. TO ZELDA

[After February 22, 1919]

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

[New York City]

MISS SELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

DARLING HEART AMBITION ENTHUSIASM AND CONFIDENCE I DECLARE EVERYTHING GLORIOUS THIS WORLD IS A GAME AND WHITE [WHILE] I FEEL SURE OF YOU LOVE EVERYTHING IS POSSIBLE I AM IN THE LAND OF AMIBITION AND SUCCESS AND MY ONLY HOPE AND FAITH IS THAT MY DARLING HEART WILL BE WITH ME SOON.

Notes:

Fitzgerald was in New York trying to succeed in the advertising business in order to marry Zelda. When she became impatient, he began making quick trips to Montgomery.

5. TO SCOTT

[February 1919]

ALS, 3 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Lover—

I drifted into school this morning, and delivered a most enlightening talk on Browning. Of cource I was well qualified, having read, approximately, two poems. However, the class declared themselves delighted and I departed with honors—I almost wish there were nothing to think of but to-morrow’s lessons and to-day’s lunch—I’d feel so to-no-purpose if it werent for you—and I know you wouldnt keep going just as well without me—that damn school is so depressing—

I s’pose you knew your Mother’s anxiously anticipated epistle at last arrived—I really am so glad she wrote—Just a nice little note— untranslatable, but she called me “Zelda”—

Sweetheart, please dont worry about me—I want to always be a help—You know I am all yours and love you with all my heart. Physically—I am prone to exaggerate my sylphiness—I’d so love to be 5 ft 4” ? 2”—Maybe I’ll accomplish it swimming. To-morrow, I’m breaking the ice—I can already feel the icicles. But the creek is delightfully clean, and me and the sun are getting hot—

Last night a small crowd of practical jokers reversed calls to University, Sewanee and Auburn—telegraphed collect all over the U.S., and were barely restrained by me from getting New York on the wire—O, you’re quite welcome—It would’ve been a good joke, but I couldn’t see the point—

Darling—lover—You know—

Zelda

Notes:

4. Prank calls to boys they knew who were attending southern colleges—the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, and Auburn University in Alabama—and were a part of the social circuit of football games and parties.

6. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

ALS, 7 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Darling, I’ve nearly sat it off in the Strand to-day and all because W. E. Lawrence of the Movies is your physical counter-part. So I was informed by half a dozen girls before I could slam on a hat and see for myself—He made me so homesick—I thought at first waiting must grow easier later—but every day I want you more—

All these soft, warm nights going to waste when I ought to be lying in your arms under the moon—the dearest arms in all the world—darling arms that I love so to feel around me—How much longer—before they’ll be there to stay? When I do get home again, you’ll certainly have a most awful time ever moving me one inch from you—

I’m glad you liked those films—I wanted them to serve as maps of your property—The best is being finished for you—Monday—but if you’re going to be so flattering, my head’ll be swelled so big then, it won’t look like me—Anyway, I am acquiring myriad wrinkles pondering over a reply to your Mother’s note—I’m so dreadfully afraid of appearing fresh or presuming or casual—Most of my correspondents have always been boys, so I am at a loss—now in my hour of need—I really believe this is my first letter to a lady—It’s really heart-rending—my frenzied efforts—Mid-night oil is burning by the well-full—O God!

An old flame from the Stone Ages is calling to-night—He’ll probably leave in disgust because I just must talk about you—I love you so, and I’m so lonesome—

Tilde leaves to-morrow at 6. A.M.—It seems as though I should be going too—I’m sure she isnt half as anxious to leave as I am—O Lover, lover you are mine—and before long—I’ll be coming to you because you are my darlin husband, and I am

Your Wife—

Notes:

5. Actor who starred in sixty-seven movies from 1912 to 1947; his 1919 films included The Girl-Woman, Caleb Piper’s Girl, and Common Clay.

6. Zelda had sent Scott pictures of herself.

7. Clothilde, the third of Zelda’s three older sisters, married to John Palmer; she was to join him in New York.

7. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

AL, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

They’re the most adorably moon-shiny things on earth—I feel like a Vogue cover in ’em—I do wish yours were touching—But I feel sure I’ll never be able to keep off the street in ’em—Does one take a lunch to bed with one in one’s pockets? One has always used her pockets for biscuit—with butter! It was waiting for me when I came home from Selma to-day—What is it? It feels like a cloud and looks like a dream—Thanks, darling—

There are two or three nice men in New York, and he is expecting me near the 11th—so I am going—travelling—I shall probably arrive with a numerous coterie collected en route, but when my husband meets me, it will dissolve, and I shall dissolve, too, in his arms—and we shall live happily ever after—I don’t care where.

“My Soldier Girl” was playing in Selma—so my male escort and I attended a rehearsal. I taught the chorus how to sling [swing?] a little, and so visited upon myself the profuse thanks of the manager— But the pool I went particularly to swim in, was closed—

Aint no use in livin’—

Just die

Aint no use in eatin’—

’Taint pie

Aint no use in kissin’—

He’ll tell

Aint no use in nothin’—

Aw Hell!

You really mustn’t say short hair thrills you—Just after I’ve lived in Vaseline, thereby turning mine dark, to make it long like you wanted it—But anyway, it didn’t grow, so I really am glad you’re becoming reconciled to the ways of convenience—I still think how nice the back of my neck would feel—Then, I think of Porphuria’s Lover—and between the two, I am remaining somewhat sane—

Darling, I guess—I know—Mamma knows that we are going to be married some day—But she keeps leaving stories of young authors, turned out on a dark and stormy night, on my pillow—I wonder if you hadn’t better write to my Daddy—just before I leave—I wish I were detached—sorter without relatives. I’m not exactly scared of ’em, but they could be so unpleasant about what I’m going to do—

But you know we will, my Sweetheart—when you’re ready—your funny little pants sorter are coming home—for you to wrinkle with the dearest arms I know—I hope you squeeze me so hard, I’ll be just as full of wrinkles as it—I hope so—

I dont see how you can carry around as much love as I’ve given you—

Notes:

8. Scott sent Zelda a gift of a glamorous pair of pajamas.

8. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

ALS, 11 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Sweetheart,

Please, please don’t be so depressed—We’ll be married soon, and then these lonesome nights will be over forever—and until we are, I am loving, loving every tiny minute of the day and night—Maybe you won’t understand this, but sometimes when I miss you most, it’s hardest to write—and you always know when I make myself—Just the ache of it all—and I can’t tell you. If we were together, you’d feel how strong it is—you’re so sweet when you’re melancholy. I love your sad tenderness—when I’ve hurt you—That’s one of the reasons I could never be sorry for our quarrels—and they bothered you so— Those dear, dear little fusses, when I always tried so hard to make you kiss and forget—

Scott—there’s nothing in all the world I want but you—and your precious love. All the material things are nothing. I’d just hate to live a sordid, colorless existence—because you’d soon love me less—and less—and I’d do anything—anything—to keep your heart for my own—I don’t want to live—I want to love first, and live incidentally—Why don’t you feel that I’m waiting—I’ll come to you, Lover, when you’re ready—Don’t—don’t ever think of the things you can’t give me. You’ve trusted me with the dearest heart of all—and it’s so damn much more than anybody else in all the world has ever had—

How can you think deliberately of life without me—If you should die—O Darling—darling Scot—It’d be like going blind. I know I would, too,—I’d have no purpose in life—just a pretty—decoration. Don’t you think I was made for you? I feel like you had me ordered—and I was delivered to you—to be worn. I want you to wear me, like a watch-charm or a button hole boquet—to the world. And then, when we’re alone, I want to help—to know that you can’t do anything without me.

I’m glad you wrote Mamma. It was such a nice sincere letter—and mine to St Paul was very evasive and rambling. I’ve never, in all my life, been able to say anything to people older than me. Somehow I just instinctively avoid personal things with them—even my family. Kids are so much nicer. Livye and a model from New York and I have been modelling in the Fashion Show—I had a misconceived idea that it was easy work—Two hours a day exhausts the most pig-iron of females—after twenty minutes, you feel like ten cents worth of fifty-dollar a yard lace—Some old fool had the sheer audacity to buy my favorite dress, so now what’ll I do to-morrow? I’ve discovered something very, very comforting by this attempt at work—that I’m really smaller than average, and I am delighted!

I mailed your picture to-day—It’s not a very characteristic pose, but maybe, if you look hard enough, there will be a little resemblance between me and the madonna—

This is Thursday, and the ring hasn’t come—I want to wear it so people can see—

All my heart—

I love you

Zelda

Notes:

9. Livye Hart, a popular friend of Zelda’s, whose family, along with the Sayres, belonged to Montgomery’s society club, Les Mysterieuses, an organization that planned entertainments and balls featuring the town’s eligible young women.

9. TO ZELDA

[March 1919]

Wire. Scrapbook

[New York City]

MISS LELDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE

MONTGY-ALA.

SWEETHEART I HAVE BEEN FRIGHTFULLY BUSY BUT YOU KNOW I HAVE THOUGHT OF YOU EVERY MINUTE WILL WRITE AT LENGTH TOMORROW GOT YOUR LETTER AND LOVED IT EVERYTHING LOOKS FINE YOU SEEM WITH ME ALWAYS HOPE AND PRAY TO BE TOGETHER SOON GOOD NIGHT DARLING.

Notes:

10. Unlike most of the other telegrams from Scott that Zelda pasted in her scrapbook, this one was not fully in capital letters. See also no. 27.

10. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

NEWYORK NY MAR 22 1919

MISS LILDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

DARLING I SENT YOU A LITTLE PRESENT FRIDAY THE RING ARRIVED TONIGHT AND I AM SENDING IT MONDAY I LOVE YOU AND I THOUGHT I WOULD TELL YOU HOW MUCH ON THIS SATURDAY NIGHT WHEN WE OUGHT TO BE TOGETHER DONT LET YOUR FAMILY BE SHOCKED AT MY PRESENT SCOTT

Notes:

11. Scott sent Zelda an engagement ring that had been his mother’s.

11. TO ZELDA

[March 24, 1919]

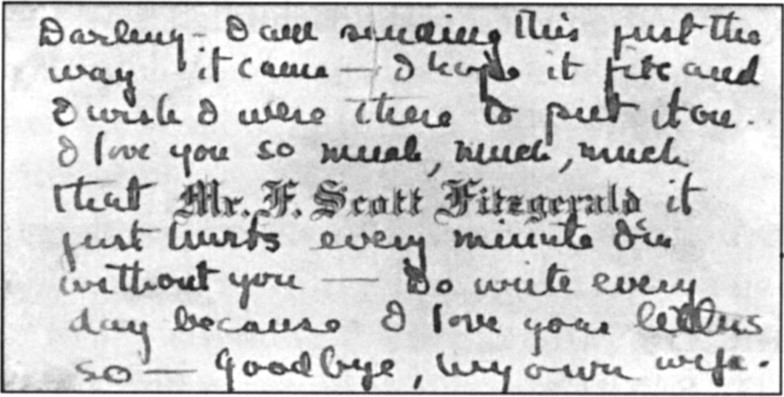

AN, 1 p. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

[New York City]

Darling: I am sending this just the way it came—I hope it fits and I wish I were there to put it on. I love you so much, much, much that it just hurts every minute I’m without you—Do write every day because I love your letters so—Goodbye, my own wife.

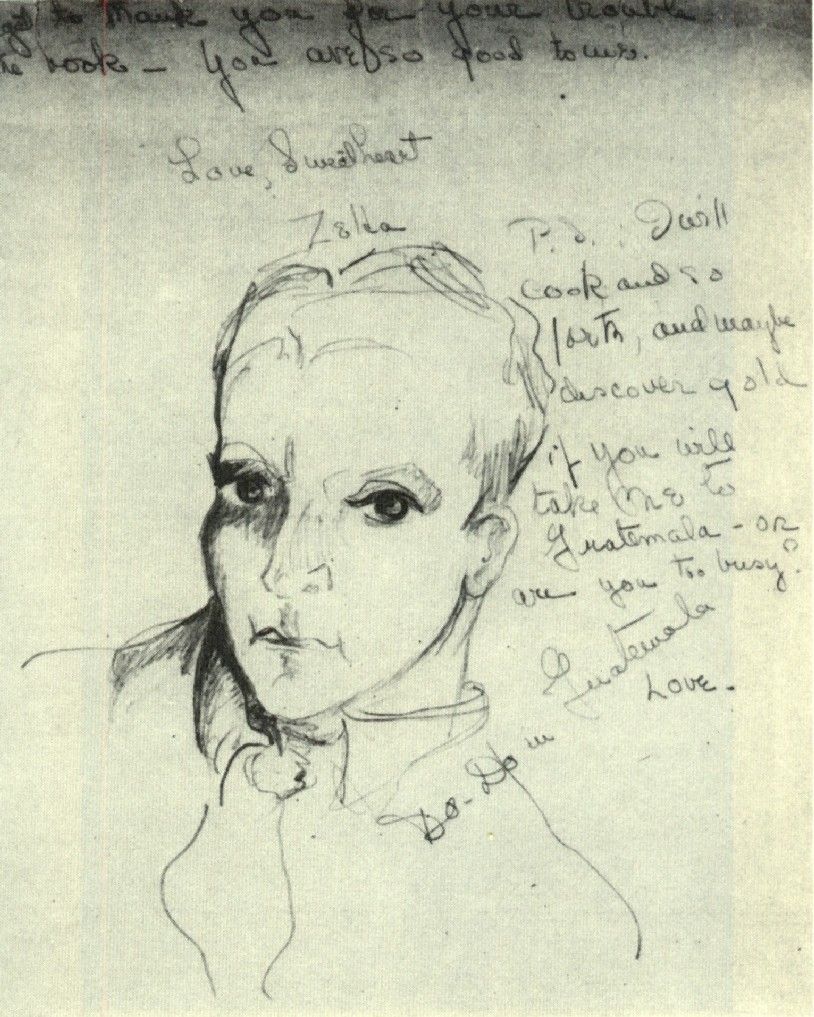

Facsimile of Scott’s March 24, 1919, note to Zelda. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Notes:

12. Written on Fitzgerald's card. Scott wrote this note to Zelda on his calling card and enclosed it with the engagement ring.

12. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

ALS, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Tootsie opened it, of cource, and I wanted to so much. She says she wants Cappy Tan to give her one like it. Scott, Darling, it really is beautiful. Every time I see it on my finger I am rather startled—I’ve never worn a ring before, they’ve always seemed so inappropriate—but I love to see this shining there so nice and white like our love—And it sorter says “soon” to me all the time— Just sings it all day long.

Thank goodness, the Fashion Show is over—wearing $500 dresses is the most strenuous task I’ve ever performed—There’s always so much hanging on to be switched around—Aren’t you glad I look like Hell in trains and slick jet dotties? Seems to me it’d be a constant source of pleasure to you that I am pink and blue.

Auburn has turned loose her R.O.T.C. with 60 loves in Montgomery—May’s is completely devastated as the result. People may be thrown out of New York restaurants for squirmy dancing, but absolutely, those boys must have studied “Popular Mechanics” for months to be able to accomplish some of their favorite feats—Can’t even be called “Chimey”—And every night I get very loud and coarse, and then I always wish for you so—so I wouldn’t be such a kid—

Darlin, I don’t know whether I exactly like the fact of having aged so perceptibly in one year. But, if you do, cource I’m glad—I’m glad “Peevie” is back, too, because I’ve always thought I’d like him best of all the people you know—

Your feet—that you liked so much—are ruined. I’ve been toe-dancing again, and nearly broke my right foot—The doctor is trying, [of] cource, but they’ll always look ugly, I guess—and I’d give half my life to have even little things like toes please you—I love you so—Sweetheart—so—

Hank Young arrived yesterday—to see me parade around in fine feathers. He was just telling me how proud of me you’d be—then May dragged him away.

Zelda

Notes:

13. Rosalind, the second of Zelda’s three older sisters.

14. Newman Smith, Rosalind’s husband, who served in France during the war.

15. Stephan Parrott, a friend of Scott’s, whom he met at the Newman School, a Catholic prep school in New Jersey.

16. Either May Inglis, a popular girl who graduated from Sidney Lanier High School with Zelda in 1918, or May Steiner, a Montgomery girl whom Scott was dating when he met Zelda.

13. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

AL, 9 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Dearest Scott—

I like your letter to A. D. and I’m slowly mustering courage to deliver it—He’s so blind, it’ll probably be a terrible shock to him but it seems the only straight-forward thing to do—I dont see how you can write such nice family letters—and really, your mother was just sparing your feelings, or else she isn’t a literary critic—I hope she’ll like me—I’ll be as nice as possible and try to make her—but I am afraid I’m losing all pretense of femininity, and I imagine she will demand it. Eleanor Browder and I have formed a syndicate— and we’re “best friends” to more college boys than Solomon had wives—Just sorter buddying with ’em and I really am enjoying it— as much as I could anything without you—I have always been inclined toward masculinity. It’s such a cheery atmosphere boys radiate—And we do such unique things—Yesterday, when the University boys took their belated departure, John Sellers wheeled me thru a vast throng of people at the station, crying intermittently “The lady hasn’t walked in five years”—“God bless those who help the poor,” the lady would echo, much to the amazement and amusement of the station at large—We had collected fo’bits when our innocent past-time was rudely interrupted by a somewhat brawny arm-of-the-law being thrust between me and the rolling-chair—I was rather vehemently denounced by the police force—In fact, we are tinting the town a crimson line—and having a delightful time acquiring a bad name—and Ed Hale has left us his cut-down Flivver while he pursue[s] educational muses at Auburn. Of cource, our lives are in continual danger, and our mothers are frantic, but Eleanor and I are enjoying the sensations we create immensely—

I guess you can tell it’s turned colder’n Blackegions by my Spencerian method—That scrawly, wiggly fist seems so inappropriate for winter. I labored for quite a while accomplishing a sunburned, open-air looking script, and almost forgot my cold-weather hand mean-time—

The fire burning again, and the old bench looking so lonesome without us, make things mighty hard—If I weren’t so sure—If I didn’t know we just had to have each other—I think I’d cry an awful lot—I can just feel those darling, darling hands—and see your shiny hair— not slick, but wrinkled, like I did it—

Good night, Sweetheart—

Notes:

17. Zelda’s father, Judge Anthony Dickinson Sayre, was sometimes called “A.D.”

18. A friend of Zelda’s from high school. In the “Composite Picture of an Ideal Senior Girl,” Zelda was voted the best mouth and Eleanor the wittiest.

14. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

AL, 3 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

I am about to sink into a sleep of utter exhaustion—Eleanor B. and I have been actually running the Street-Car all day—We were quite a success in our business career until we ran it off the track. Then we got fired—but we were tired, anyway! Mothers of our associates just stood by and gasped—much to our glee, of cource— Things like the preceeding incident are our only amusement—

Darling heart, I love you—truly. You are my sweetheart—and I do—I do

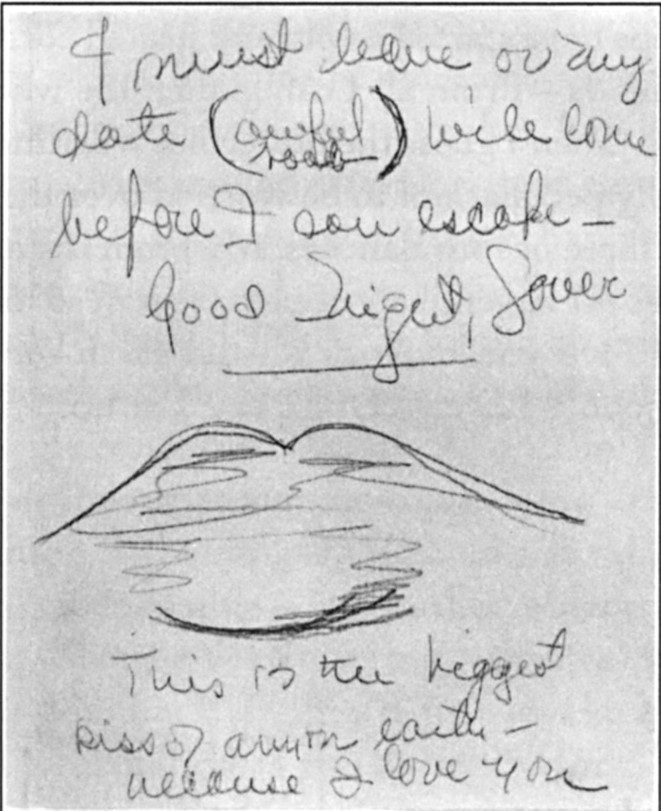

I must leave or my date (awful boob) will come before I can escape—

Good Night, Lover

This is the biggest kiss of any on earth—because I love you

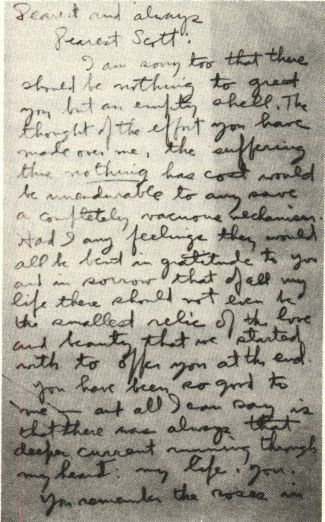

Facsimile of last page of Zelda’s March 1919 letter to Scott, with drawing of a kiss. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

15. TO SCOTT

[March 1919]

AL, 4 pp.; Correspondence.

[Montgomery, Alabama] Sunday—

Darling, darling I love you so—To-day seems like Easter, and I wish we were together walking slow thru the sunshine and the crowds from Church—Everything smells so good and warm, and your ring shines so white in the sun—like one of the church lillies with a little yellow dust on it—We ought to be together [in] the Spring—It seems made for us to love in—

You can’t imagine what havoc the ring wrought—a whole dance was completely upset last night—Everybody thinks its lovely—and I am so proud to be your girl—to have everybody know we are in love. It’s so good to know youre always loving me—and that before long we’ll be together for all our lives—

The Ohio troops have started a wild and heated correspondence with Montgomery damsels—From all I can gather, the whole 37th Div will be down in May—Then I guess the butterflies will flitter a trifle more— It seems dreadfully peculiar not to be worried over the prospects of the return of at least three or four fiancees. My brain is stagnating owing to the lack of scrapes—I havent had to exercise it in so long—

Sweetheart, I love you most of all the earth—and I want to be married soon—soon—Lover—Don’t say I’m not enthusiastic—You ought to know—

16. TO ZELDA

[April 1919]

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

[New York City]

MISS TELDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA TELDA FOUND KNOCKOUT LITTLE APARTMENT REASONABLE RATES I HAVE TAKEN IT FROM TWENTY SIXTH SHE MOVES INTO SAME BUILDING EARLY IN MAY BETTER GIVE LETTER TO YOUR FATHER IM SORRY YOURE NERVOUS DONT WRITE UNLESS YOU WANT TO I LOVE YOU DEAR EVERTHING WILL BE MIGHTY FINE ALL MY LOVE

Notes:

19. Scott visited Zelda’s sister Clothilde in New York while looking for an apartment for himself and Zelda.

1 Zelda's sister Clothilde was called Tilde.

2 Fitzgerald had written a formal letter to Judge Sayre requesting Zelda's hand in marriage.

17. TO SCOTT

[April 1919]

ALS, 7 pp. 6 Pleasant Ave., Montgomery, Ala.

Dearest—

Your letters make things seem so close—and you always said I’d wire I was “scared, Scott”—I’m really not one bit afraid—I love you so—and April has already started!

I’m glad you went to see Tilde—I guess you are too, now that it’s over—she already writes Mamma of moving—says she never sees a single tree from her windows, and it makes her homesick—This end of the family just sits around straining their ears for Miss Bootsie’s little grunts and squeals—the Judge has relapsed into his usual grouch since she left—I guess they’ll be pretty lonesome without me to disturb them—Toots is taking an uproarious departure in about a week—She certainly makes life obnoxious sometimes. I hate people who can’t do anything calmly. When I meet persons who act as if everything, anything, were exactly what they expected and wanted, I always gasp with admiration—They always make me feel so irresponsible—and rather objects to be pitied— they love to fancy themselves suffering—they’re nearly all moral and mental hypo-crondiacs. If they’d just awake to the fact that their excuse and explanation is the necessity for a disturbing element among men—they’d be much happier, and the men much more miserable—which is exactly what they need for the improvement of things in general.

I’ve just found, in Major Smith’s old books a Masonic Chart, in hieroglyphics, of cource, which is puzzling me sorely—It’s a very queer—religion?—and with the help of pencilled notes, I am about to fathom unfathomable secrets—If I could just stop reading “Scott” in every line I’d make more progress—

Kiss me, Lover—one darling kiss—I need you so—

Zelda

Notes:

20. The Sayres’ cat, which apparently moved to New York with Clothilde.

21. Same as Tootsie, Zelda’s sister Rosalind.

22. Newman Smith, Rosalind’s husband.

18. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

S1 NEWYORK NY 250PM APRIL 14 1919

MISS TELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

AM TAKING APARTMENT IMMEDIATELY RIGHT UNDER TILDES NEW APARTMENT LOVE

SCOTT

19. TO SCOTT

[April 1919]

ALS, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

I feel like a full-fledged traveller—by the 18th I’ll be well qualified for my trip—In desperation, yesterday Bill LeGrand and I drove his car to Auburn and came back with ten boys to liven things up—Of cource, the day was vastly exciting—and the night more so—Thanks to a jazz band that’s been performing at Mays between Keith shows. The boys thought I’d be a charming addition to their act, and I nearly entered upon a theatrical career—

Scott, you’re really awfully silly—In the first place, I haven’t kissed anybody good-bye, and in the second place, nobody’s left in the first place—You know, darling, that I love you too much to want to. If I did have an honest—or dishonest—desire to kiss just one or two people, I might—but I couldn’t ever want to—my mouth is yours. But s’pose I did—Don’t you know it’d just be absolutely nothing— Why can’t you understand that nothing means anything except your darling self and your love—I wish we’d hurry and I’d be yours so you’d know—Sometimes I almost despair of making you feel sure—so sure that nothing could ever make you doubt like I do—

Charlie Johnson has arisen from the depths of oblivion—I thought he was dead—and he’ll be home Easter. Seems almost like old times again—I wish you could get a glimpse of Montgomery like it really is—without the camp disturbing things so—and you’d know why I love it so—

We are donning men’s clothing to-night—to take in some picture on Commerce St. It promises disaster, but it’s by far the most madcap of my escapades, so I’m looking forward to the dusk with great excitement. We are dragging Willie Persons along for protection—he’s effeminate—and won’t show us up so much. I could knock him out in one round—but my fertile brain is certainly being cooked over-time thinking up sure-deaths to reputations—

Darling—darling I love you so—and I’m going to—all my life—

Zelda

20. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

NEWYORK NY APRIL 15 1919 3AM

MISS TILDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

ARRIVE MONTGOMERY WEDNESDAY EVENING

21. TO SCOTT

[After April 15, 1919]

AL, 8 pp.; Correspondence.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Scott, my darling lover—everything seems so smooth and restful, like this yellow dusk. Knowing that I’ll always be yours—that you really own me—that nothing can keep us apart—is such a relief after the strain and nervous excitement of the last month. I’m so glad you came—like Summer, just when I needed you most—and took me back with you. Waiting doesn’t seem so hard now. The vague despondency has gone—I love you Sweetheart.

Why did you buy the “best at the Exchange”?—I’d rather have had 10? a quart variety—I wanted it just to know you loved the sweetness—To breathe and know you loved the smell—I think I like breathing twilit gardens and moths more than beautiful pictures or good books—It seems the most sensual of all the sences. Something in me vibrates to a dusky, dreamy smell—a smell of dying moons and shadows—

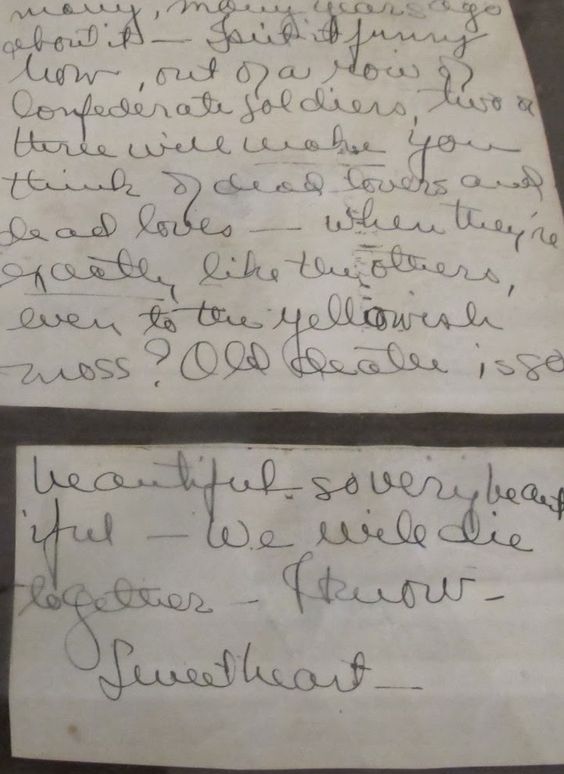

I’ve spent to-day in the grave-yard. It really isn’t a cemetery, you know,—trying to unlock a rusty iron vault built in the side of the hill. It’s all washed and covered with weepy, watery blue flowers that might have grown from dead eyes—sticky to touch with a sickening odor— The boys wanted to get in to test my nerve—to-night—I wanted to feel “William Wreford, 1864.” Why should graves make people feel in vain? I’ve heard that so much, and Grey is so convincing, but somehow I can’t find anything hopeless in having lived—All the broken columnes and clasped hands and doves and angels mean romances— and in an hundred years I think I shall like having young people speculate on whether my eyes were brown or blue—of cource, they are neither—I hope my grave has an air of many, many years ago about it—Isn’t it funny how, out of a row of Confederate soldiers, two or three will make you think of dead lovers and dead loves—when they’re exactly like the others, even to the yellowish moss? Old death is so beautiful—so very beautiful—We will die together—I know—

Sweetheart—

Notes:

23. The Hotel Exchange in Montgomery, where Scott bought a bottle of gin when he visited Zelda.

24. Scott took this romantic description of a graveyard and used it nearly verbatim as the thoughts of the protagonist Amory Blaine, a thinly disguised fictional version of himself, in the final two pages of This Side of Paradise.

1 Fitzgerald had bought a bottle of liquor at the Exchange Hotel when he visited her.

2 Fitzgerald used this graveyard description in This Side of Paradise, pp. 303-04.

22. TO SCOTT

[April 1919]

AL, 5 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Those feathers—those wonderful, wonderful feathers are the most beautiful things on earth—so soft like little chickens, and rosy like fire-light. I feel so rich and pompous waving them around in the air and covering up myself with ’em. Darling, it is the prettiest thing in the world, and you were so sweet to send it—That color is rather becoming.

Aunt Annabel is certainly a procrastinator—I was wondering if pop-calls were hereditary, but I guess you just acquired the fancy. I don’t s’pose now, tho, her visit’s very momentous—except, of cource, that you’ll be glad to see her. I know, Sweetheart, that we aren’t going to need her—Don’t ask me to have more faith—I love you most of everything on earth, and somehow you[r] visit made things so much saner, and I do believe in you—Just the wild rush and knowing what you did was distasteful to you made me afraid—I’d die rather than see you miserable, and you know you hated looking incessantly at banannas and ice-cream before lunch.

I want to go to Italy—with you, Darling—It seems so yellow— dull, mellow yellow—and that’s your color—and I’d feel so like there was nobody else is [in] existence but just you’n me—

Les Mysterieurs is holding a rehearsal on me—I think I’m going [to] look cute in my ballet-dress—

I love you, Scott, with all my heart—

Notes:

25. Nancy Milford says that Scott, “[t]ouched by the beauty of” Zelda’s previous letter (letter 20), “sent her a marvelous flamingo-colored feather fan. It was the perfect gift for Zelda, frivolous and entirely beautiful; she was delighted by it” (Zelda 46).

26. Scott’s maiden aunt, who had helped finance his education.

27. Les Mysterieuses: Zelda’s mother and sister Rosalind wrote a skit for the April “Folly Ball,” in which Zelda performed.

23. TO SCOTT

[April 1919]

ALS, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Sweetheart, Sweetheart, I love you so—and I get so lonesome when I never get a letter—you were very sweet and thoughtful to send the music—but I wish you had just scribbled on the cover what I live to hear you say. I can ’t tell you in “ten words”—or ten volumes, or ten years. I can’t even tell you a new way—But, please, Darling, try not to get tired of the old one—

We’re having the Vaudeville to-night—and I’m leading “Down on the Farm”—in overalls—And, thank Goodness I’ve lost my sandals, so I guess I’ll have to dance bare-foot—and probably suffer more injuries thereby. I think I could do so much better if you were in the audience—Everytime I look nice—or do anything I mentally applaud, I always wish for you—just to hear you say you like it—

“Marcus Aurelius” is my literature in the absence of your letters—Tootsie thinks he’s most remarkable. I guess he was, for his day, but now it’s all just platitudes. All philosophy is, more or less—It seems as if there’s no new wisdom—and surely people haven’t stopped thinking. I guess morality has relinquished it’s claim on the intellect—and the thinkers think dollars and wars and politics—I don’t know whether it’s evolution or degeneration—

Look at this communication from Mamma—all on account of a wine-stained dress—Darling heart—I won’t drink any if you object—Sometimes I get so bored—and sick for you—It helps then—and afterwards, I’m just more bored and sicker for you—and ashamed—

When are you going to marry me—I don’t want to repeat those two months—but I’ve just got to have you—when you can—because I love you, my husband—

Zelda

Zelda

If you have added whiskey to your tobacco you can substract your Mother. I am no Mrs. Guinvan however much you are like Susie. If you prefer the habits of a prostitute don’t try to mix them with gentility. Oil and water do not mix.

Notes:

28. The local Junior League put on a variety show, the proceeds of which were to be sent to “the Alabama boys in France.”

29. The philosopher and emperor of ancient Rome, who wrote Meditations, a classic work of stoicism.

30. This two-page handwritten note from Zelda’s mother to her daughter was enclosed.

24. TO SCOTT

[May 1919]

ALS, 8 pp.; Correspondence.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Dearest Scott—

T. G. that’s over! The vaudeville, I mean, and I am a complete wreck—but everybody says the dance was a success. It nearly broke my heart to take off those lovely Oriental pants—Some actor with this week’s Keiths tried to take me and Livye on the road with him— but I can’t ignore physical characteristics enough to elope with a positive ape. And now I’ve got just two weeks to train a Folly Ballet for Les Mysterieurs—

“Plasher’s Mead” has been carefully perused—Thanks awfully for it. I haven’t read in so long—but I don’t really like it—People seldom interest me except in their relations to things, and I like men to be just incidents in books so I can imagine their characters. Nothing annoys me more than having the most trivial action analyzed and explained. Besides, Pauline is positively atrociously uninteresting— I’ll save the book and re-read it in rainy weather in the Fall—I think I’ll appreciate it more—

Scott, you’ve been so sweet about writing—but I’m so damned tired of being told that you “used to wonder why they kept princesses in towers”—you’ve written that verbatim, in your last six letters! It’s dreadfully hard to write so very much—and so many of your letters sound forced—I know you love me, Darling, and I love you more than anything in the world, but if its going to be so much longer, we just can’t keep up this frantic writing. It’s like the last week we were to-gether—and I’d like to feel that you know I am thinking of you and loving you always. I hate writing when I haven’t time, and I just have to scribble a few lines. I’m saying all this so you’ll understand—Hectic affairs of any kind are rather trying, so please let’s write calmly and whenever we feel like it.

I’d probably aggravate you to death to day. There’s no skin on my lips, and I have relapsed into a nervous stupor. It feels like going crazy knowing everything you do and being utterly powerless not to do it—and thinking you’ll surely scream next minute. You used to blame it all on poor Bill—and all the time, it was just my nastiness—

Mamma gave me this to-day—I s’pose it’s another of her subtle suggestions—

All my love

Zelda

Notes:

31. A novel by the popular English writer Compton Mackenzie.

32. When Scott returned to New York after his April 15 visit to Zelda, he wrote in his Ledger: “Failure. I used to wonder why they locked princesses in towers” (Ledger 173). He apparently liked the sentence so much that he used it in letters to Zelda as well.

33. Missing; probably a clipping about a ruined writer. Whatever Zelda’s mother had given her has been lost. Mrs. Sayre, however, was in the habit of giving her daughter clippings of news articles about failed writers, and perhaps this was one.

25. TO SCOTT

[May 1919]

AL, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

The Fourth Alabama arrives Tuesday, and town looks like Mardi Gras—Perry St. is just one long booth with flags and confetti everywhere—The houses for three blocks around the Governor’s are open—or will be—and everybody’s dragging out old costumes and masks—and Good Lord, it’s hot! Commerce St. is just a long arch— Rosemont Garden’s has turned over it’s greenhouse for a flowerbarage. I wish you could see it—but, of cource, everybody’s asleep all up and down the streets. Everything is so delightfully slow, even now. Major Smith’s company that he took over is going to march with the ranks unfilled—Twenty-three men—It almost makes me cry—I would if I weren’t expending all my energy on gum—I’ve started a continuous chew again. Your disapproval used to put me on the wagon, but now I’ve got the habit again—

To-morrow, a man’s going to make some Kodak snaps of me in my Folly dress, and cource I’ll send them to you—Mamma gets rather annoying about her rose-bushes at times, so I s’pose I’ll be perched on the topmost thorn on one of ’em. She bids me tell you how beautiful they are—Even if you didn’t go into ecstacies over Mrs. McKurneys when they weren’t bloomed—

My poor limbs have suffered another accident. Jumping off a sandbank tall as the moon—nearly—and landing in a pile of rocks almost makes me wish them amputated. Little boys are almost too strenuous for my old age. Darling Sweetheart, I’ll be so glad to see you again—

Are you coming on the 20th, or had you rather wait till early June when I’ll be going to Georgia Tech commencement and can go as far as Atlanta with you on your way back? The family threatens to depart for Asheville, N.C. in July—Wouldn’t it be nice if you needed a rest about then and spent a week or two in the mountains with me? However, I cordially loathe consumptives and babies with heat, which constitu[t]e one’s circle of acquaintances there—

I’ve tried so many times to think of a new way to say it—and its still I love you—love you—love you—my Sweetheart—

Notes:

34. A regiment that had been serving in France.

35. Twenty-three of the men in her brother-in-law’s regiment died in France.

36. Zelda had her picture taken in her costume for the April “Folly Ball” in her backyard, sitting among Mrs. Sayre’s rose bushes, and sent it to Scott.

37. Ironically, Highland Hospital—where Zelda was a patient in the 1930s and 1940s and where she died tragically in a fire in 1948—was in Asheville, North Carolina.

26. TO SCOTT

[May 1919]

AL, 9 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

A beautiful golden kitty would be nice—but I wouldn’t swap my cat for two of ’em, and he would probably kill the new one—Besides, I lost my brush and mirror at Cobb’s Ford, and I’d love to have one with pink flowers around the edge. Just so you come, Darling—

Mrs. Francesca—who never heard of you—got a message from Ouija for me. Nobody’s hands were on it but her’s—and it told us to be married—that we were soul mates. Theosophists think that two souls are incarnated to-gether—not necessarily at the same time, but are mated—since the time when people were bi-sexual, so you see “soul-mate” isn’t exactly Snappy-Storyish, after all. I can’t get messages, but it really moved for me last night—only it couldn’t say anything but “dead, dead”—so, of cource, I got scared and quit. It’s really most remarkable, even if you do scoff. I wish you wouldn’t, it’s so easy, and believing is much more intelligent.

We are going to Asheville in July—definitely—but we’ll have some trouble over the “thirty moonlights”—I’m afraid some of the nights may be lacking the moon—But, Sweetheart, we’ll be to-gether a whole month,—and moons dont really matter, anyway. I think I’m going to bob my hair, and that may evoke a furor. I wish you’d tell me if you’ll like it—Everybody’s so discouraging—but think how good it’d feel in the water! I’ll probably look like Hell.

“Red” said last night that I was the pinkest-whitest person he ever saw, so I went to sleep in his lap. Of cource, you dont mind because it was really very fraternal, and we were chaperoned by three girls—

Darling Scott—please come—I love you with all of me—and I’ll be so very, very glad to see you—We’re going to repeat the Vaudeville on the 20th—maybe you’d like to see it—but we’re in the midst of terrible upheaval—The cast is being revised—and I dont think they’re going to let me sing—It’s funny, but I really do think I sing well—

Look at this fist—It’s grown rusty and dreadfully spasmodic— Just translate it into what I’m always thinking—Sweetheart—

Notes:

38. Mrs. Francesca, a local spiritualist, who claimed to receive messages from the “other world” on a Ouija board.

39. Snappy Stories, a popular bimonthly pulp magazine, published formulaic short stories, articles, cartoons, and reviews of movies and plays.

27. TO SCOTT

[Late May 1919]

ALS, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

One more afternoon as strenuous as this, and I’ll be [a] fit inmate for the morgue—Having seen the Vaudeville last night, Livye and I went again to-day to see the dance in the last act so we could put it on for the League show—We were discussing the costumes—very calmly and not one bit drunk or disorderly, when a howling hussy over the foot-lights stopped the orchestra, and demanded in her loudest voice whether “she was going to talk, or we were”—Of cource, the audience went into an uproar instantly, and pandemonium broke loose—After glaring at us for five minutes, she continued the song—to the best of her ability above the noise. The first three rows are already bought for to-morrow’s matinee— the boys are indignant, and I am expecting no less than a ten-round bout—Here’s the point to the joke: We really weren’t annoying a soul. May was back of us, and even she says she couldn’t hear us talking.

She asked me to say she’d be in New York the end of this week, and that she’d call you up. All her beautiful hair came out when she had Flu, and she’s coming up to have it treated. It makes me sorter sick at heart to see her head. It used to be so pretty and curly.

Joel Massie, too, is sending his utmost. He makes a desperate effort at ragging me—as if I could be teased—you’d probably like this now—lots of boys like Jo are back, and things seem more dignified.

Toots is packing her truck—nearly—Cincinnati the first week in May—then New York—Please hurry—I want so much to come— and if that man feels that he must bust loose, for Lawd’s sake shield our timidity from his generosity—He evidently isn’t acquainted with my habits, or he’d realize that meals by lamp-light aren’t exactly breakfasts—

I love you, Darling—and I’m waiting—

Zelda

Please—please—aren’t you ever going to learn that boys never appreciate things other men tell them on their girls? At least five men have suffered a bout behind the Baptist Church for no other offense than you are about to committ, only I was the lady concerned—in the dim past—Anyway, if she is good-looking, and you want to one bit—I know you could and love me just the same—

28. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

NEWYORK MAY 14–19

MISS LELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGY ALA

ARRIVE MONTGOMERY EIGHT THIRTY THURSDAY NIGHT LOVE

SCOTT

29. TO SCOTT

[May 1919]

AL, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Darling Scott, you don’t know how I miss your letters—This morning, I thought you’d written me such a nice fat one, and it was your story—I haven’t heard but once since you left—But I like the little tale—“Clayton” has just been here with Keith’s and even the stage-setting was identical. He suffered a broken head and a hasty departure from here by shrieking, in answer to Mrs. Byar’s question “Is my daughter all right” that her daughter was three months all wrong. The town has been in a dreadful uproar. I think he’s fine, tho, cause he said I’d be in New York before October—It seems so far away, and I love you so—

The sweater is perfectly delicious—and I’m going to save it till you come in June so you can tell me how nice I look. It’s funny, but I like being “pink and helpless”—When I know I seem that way, I feel terribly competent—and superior. I keep thinking, “Now those men think I’m purely decorative, and they’re just fools for not knowing better”— and I love being rather unfathomable. You are the only person on earth, Lover, who has ever known and loved all of me—Men love me cause I’m pretty—and they’re always afraid of mental wickedness—and men love me cause I’m clever, and they’re always afraid of my prettiness— One or two have even loved me cause I’m lovable, and then, of cource, I was acting. But you just do, darling—and I do—so very, very much—

I think I’m beginning to realize the seriousness of us—Little things, like and small familiarities—I used to do them thoughtlessly—and now I can’t, because I love you, so I’ve quit Chummying. I’ll never learn the combination. Maybe I’m getting tired—I can’t think of anything but nights with you—I want them warm and silvery—when we can be to-gether all our lives—Which will probably be long, as I’ve recovered from the cough, much to my disgust. I don’t want you to see me growing old and ugly—I know you’ll be a beautiful old man—romantic and dreamy—and I’ll probably be most prosaic and wrinkled. We will just have to die when we’re thirty. I wish your name were Paul—or Jacquelyn. I’m going to name all our children that—and Peter—yours and mine—because we love each other—

Notes:

40. Perhaps Scott had sent her his short story “Babes in the Woods”; he had just sold the story to The Smart Set for thirty dollars, out of which he bought a sweater for Zelda and white flannel trousers for himself.

41. At this point in the letter, Zelda drew a picture of two stick figures dancing.

42. Zelda inserted “I’ll never learn the combination” above “Chummying” and drew an arrow circling these words and pointing to the two stick figures that she had drawn.

30. TO SCOTT

[June 1919]

AL, 4 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

No wonder I never hear from you—The New York post-office has been communicating wildly regarding two letters with no postage. Circumstantial evidence against you—looks like wild nights and headachy mornings—I was scared you had forgotten me—It’s been so long since I had a letter. I’ve been seeking consolation in a perfectly delightful golf-tournament—Perry Adair and all the Atlanta celebrities were over, so of cource, I wouldn’t miss Tech commencement for a million. I’ll be in Atlanta till Wednesday, and I hope—I want you to so much—you’ll come down soon as I get back. Darling heart, I love you—It’s been so long since you left me—much more than the three weeks you promised—and sometimes I feel like I’ll die without you—But you’re coming—and please take me with you.

Your pictures are ready—but I haven’t got any money, as usual, so I wish you’d send for ’em.

I do—hope I get a letter to-morrow—and

I do—love you with all my heart.

31. TO SCOTT

[June 1919]

ALS, 6 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Dearest Ole Dear—

I’m back home again—and, as usual, had the most fun I ever had. God, Scott, if you waited till I got tired we’d certainly both be bachelors—Every time, it improves, and I’ll never feel grown. I absolutely despair of it. But if I wait much more I’d have to go in a wheel-chair and return in a hearse. This time the casualty list was unusually long—both eyes and a leg, a couple of tonsils and a suit-case full of clothes: all lost in action. And still I’m so mighty happy—It’s just sort of a “thankful” feeling—that I’m alive and that people are glad I am.

There’s nothing to say—you know everything about me, and that’s mostly what I think about. I seem always curiously interested in myself, and it’s so much fun to stand off and look at me—

But this:

I know you’ve worried—and enjoyed doing it thoroughly—and I didn’t want you to because something always makes things the way they ought to be—Even this time—and its all right—Somehow, I rather hate to tell you that—I know its depriving you of an idea that horrifies and fascinates—you’re so morbidly exaggerative—Your mind dwells on things that don’t make people happy—I can’t explain, but its rather kin to the way kids 13 feel when everybody goes off and leaves them at home—if they aren’t scary, of cource. Sort of deliberately experimental and wiggly—

In Tuscaloosa I saw Katherine Ellesberry’s baby. It’s darling and it’s gotten round. I’m so glad—I hate long children. I felt like I’d sorter like to have it.

Scott, dear boy, I love you—and, thank Heavens, events can take a natural cource—

Write me, please—

Zelda

32. TO SCOTT

[June 1919]

ALS, 5 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Dearest Scott—

I certainly appreciated your last letter. It must have been a desperate struggle to write it, but your efforts were not wasted on an unreceptive audience. Just the same, the only thing that carried me thru a muddy, rainy, boring Auburn commencement was the knowledge that I’d have a note, at least, from you when I got home—but I didn’t. I was so sure—because I left Wed. and you hadn’t written in a week—Not that letters make so much difference, and if you don’t want to write we’ll stop, but I love you so—and I hate being disappointed day after day.

I’m glad you’re coming. Make it any time except the week of June 13. I’m going to Georgia Tech to try my hand in new fields—You might come on the 20th and stay till we go to North Carolina—or come before I go to Atlanta, only I’ll be mighty tired, and they always dance till breakfast.

The picture in the hat is an awful bother—Tresslar won’t make less than three, and won’t send a fifteen-dollar bill to New York, so please remit, and I’ll send my beaming likeness when I get it—next week.

Zelda—

33. TO SCOTT

[June 1919]

ALS, 2 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

You asked me not to write—but I do want to explain—That note belonged with Perry Adair’s fraternity pin which I was returning. Hence, the sentimental tone. He has very thoughtfully contributed a letter to you to the general mix-up. It went to him, with his pin.

I’m so sorry, Scott, and if you want the pictures, I’ll mail them to you.

Zelda

Notes:

43. When Zelda returned home from Georgia Tech, she was pinned to the golfer Perry Adair but she soon regretted it and returned Adair’s fraternity pin by mail. She inadvertently mixed up a “sentimental” note she had written to him with a letter she was writing to Scott. Unfortunately, Scott got the note intended for Adair and was so hurt and angry that Zelda had been disloyal to him that he demanded that she never write to him again. Zelda could not comply, and she sent this brief explanation and apology. After receiving this letter, Scott made a frantic trip to Montgomery to try to patch up the relationship. He begged Zelda to marry him immediately, but she refused and broke their engagement. There were no more letters until they resumed their relationship in the fall.

34. TO SCOTT

[October 1919]

ALS, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Dearest Scott—

Nov. 1—Columbus—sponsor Auburn-Ga. game THANKSGIVING—ATLANTA ditto AUBURN-TECH—

So, you see, you’ll be down just about the right time. It’s awfully hard to do everything by a foot-ball schedule, but I’ve been making a frantic effort at it for the last month. Between the games and my piano-lessons I’ll probably be a mere shadow of the girl I once was by the time you come, but I guess you’ll recognize me. Anyway, in case of emergency, you can notify my parents at the same old Six Pleasant.

I’m mighty glad you’re coming—I’ve been wanting to see you (which you probably knew) but I couldn’t ask you—and besides Mrs. McKinney has run me positively crazy planning weddings in her atrocious magnolia hall until I was almost wishing you’d never come anymore. It’s fine, and I’m tickled to death.

And another thing:

I’m just recovering from a wholesome amour with Auburn’s “starting quarter-back” so my disposition is excellent as well as my health. Mentally, you’ll find me dreadfully detiorated—but you never seemed to know when I was stupid and when I wasn’t, anyway—

Please bring me a quart of gin—I haven’t had a drink all summer, and you’re already ruined along alcoholic lines with Mrs. Sayre. After you left, every corner the nigger started cleaning was occupied by a bottle (or bottles). Tootsie, of cource, is largely responsible—but it was just one of those incidents that cant be explained. She thought you drank at least 12 qts. in two days.

‘S funny, Scott, I don’t feel a bit shaky and “do-don’t” ish like I used to when you came. I really want to see you—that’s all—

Zelda

Beautiful color scheme—n’est-ce pas? [I’m a madamoiselle]

Notes:

44. These brackets were supplied by Zelda.

35. TO SCOTT

[Fall 1919]

AL, 8 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

I am very proud of you—I hate to say this, but I, don’t think I had much confidence in you at first—I was just coming anyway—It’s so nice to know that you really can do things—anything—and I love to feel that maybe I can help just a little—I want to so much—Don’t ask Mr. Hooker about me—I might try and be dreadful and then you’d be so ashamed of me—Why don’t you write the things? Lyrics sound easy—but you know best, of cource. I’m so damn glad I love you—I wouldn’t love any other man on earth—I b’lieve if I had deliberately decided on a sweetheart, he’d have been you—I thought that at first when we couldn’t find each other—Years ago, when you wouldn’t pretend, and I called you Don Juan—and you thought I was Eleanor—and discovered that I really wasn’t a thing on earth but your own true sweetheart—

Don’t—please—accumulate a lot of furniture. Really, Scott, I’d just as soon live anywhere—and can’t we find a bed ready-made? Someday, you know we’ll want rugs and wicker furniture and a home—I’m terribly afraid it’ll just be in the way now. I wish New York were a little tiny town—so I could imagine how it’d be. I haven’t the remotest idea of what it’s like, so I am afraid to make any suggestions—What became of the apartment the men decorated? I liked that—I was picturing walls covered with huge orange and black fruit—and yellow ceilings—

Mrs Hayden is bringing her daughter, Edwine, down Easter— Tilde and Tootsie have both visited them, and, of cource, we’re obligated—Toots is threatening to go with Mrs. DeFuniac to Michigan—She leaves Friday—If she does, I’ll have to stay and entertain Edwine—Then, when they leave, I could come North with them— That’s why I wanted you to write Mamma. You see, I can’t tell them why Tootsie just can’t go to Michigan—What must I do?

Craighead telegraphed he was coming from Gordon for the weekend. I’ll be glad to see him—There’re absolutely no males in this vicinity and, besides, I can tell him about you. I love talking of you— Darling—you’re all—everything in the world—I love you so—

In case of, emergency—

Here’s Tilde—

520 W 124th St Apt. 51

Lover—lover—I want you—always—

36. TO SCOTT

[Fall 1919]

ALS, 9 pp.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

I’m writing on this beautiful paper which everybody thinks is so awful and which I hate to use for fear it’ll use up to thank you—so you know how much I like the “two little junks”—But I’m so distressed over not finding a place to put the picture in the case that I’m going to glue it somewhere even if it’s on the outside. Please don’t look so horrified. It’s a company case, anyway—The chain is just like a hat on a lady, shrieking “take me somewhere—take me somewhere,” and I do love to take it—You know how I like things that nobody around’s ever had, and the tassel on the other thing has elevated me to a most superior position.

Yesterday I almost wrote a book or story, I hadn’t decided which, but after two pages on my heroine I discovered that I hadn’t even started her, and, since I couldn’t just write forever about a charmingly impossible creature, I began to despair. “Vamping Romeo” was the name, and I guess a man would have had to appear somewhere before the end. But there wasn’t any plot, so I thought I’d ask you how to decide what they’re going to do. Mamma answered my S.O.S. with one of O. Henry’s, verbatum, which I discarded because he never created people—just things to happen to the same old kind of folks and unexpected ends, and I like stories with all the ladies like Constance Talmadge and the men just sorter strong, silent characters or college boys—but I know I’m going to be rather fond of Margery See and maybe she’ll fire me with enough ambition to carry Romeo thru two more pages—And so you see, Scott, I’ll never be able to do anything because I’m much too lazy to care whether it’s done or not—and I don’t want to be famous and feted—all I want is to be very young always and very irresponsible and to feel that my life is my own—to live and be happy and die in my own way—to please myself.

And, Scott, Darlin’ don’t try so hard to convince yourself that we’re very old people who’ve lost their most precious possession. We really havent found it yet—and only weaklings like the St. Paul girl you told me about who lack courage and the power to feel they’re right when the whole world says they’re wrong, ever lose—All the fire and sweetness—the emotional strength that we’re capable of is growing—growing and just because sanity and wisdom are growing too and we’re building our love-castle on a firm foundation, nothing is lost—That first abandon couldn’t last, but the things that went to make it are tremendously alive—just like blowing bubbles—they burst, but more bubbles just as beautiful can be blown—and burst— till the soap and water is gone—and that’s the way we’ll be, I guess— so don’t mourn for a poor little forlorn, wonderful memory when we’ve got each other—Because I know I love you—and you’ll come in January to tell me that you do—and we won’t worry any more about anything—Zelda

Notes:

45. Most likely the heroine of her story.

37. TO ZELDA

[Before January 9, 1920]

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

[New York City]

I FIND THAT I CANNOT GET A BERTH SOUTH UNTIL FRIDAY OR POSSIBLY SATURDAY NIGHT WHICH MEANS I WON’T ARRIVE UNTIL THE ELEVENTH OR TWELFTH PERIOD AS SOON AS I KNOW I WILL WIRE YOU THE SATURDAY EVENING POST HAS JUST TAKEN TWO MORE STORIES PERIOD ALL MY LOVE.

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald was going to New Orleans to write.

2 Probably "Myra Meets His Family" (20 March 1920), "The Camel's Back" (24 April 1920), or "Bernice Bobs Her Hair" (1 May 1920).

38. TO ZELDA

[January 1920]

Wire. Scrapbook

STPAUL MINN 254P 10

MISS LELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE. MONTGOMERY ALA.

ARRIVE MONDAY

SCOTT FITZGERALD

39. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

NEWORLEANS LA 1213P JAN 19 1920

MISS ZELDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

SEND MANUSCRIPT SPECIAL DELIVERY LOVE

SCOTT

Notes:

46. Concerned about tuberculosis, Scott went to New Orleans in January to write and to avoid the St. Paul winter. While there, he visited Zelda in Montgomery twice, during which Scott and Zelda made love, probably for the first time. Scott moved back to New York in February; then, toward the end of February, he moved to the Cottage Club at Princeton to await the publication of This Side of Paradise.

47. Perhaps Scott was asking Zelda to send him the story that she was working on (mentioned in letter 35).

40. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

NEWORLEANS LA 530P JAN 29 1920

MISS ZELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

COMING UP SATURDAY AND SUNDAY WIRE ME ONLY IF IN-CONVENIENT

SCOTT

41. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

NEWYORK NY FEB 24 1920

MISS LIDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

I HAVE SOLD THE MOVIE RIGHTS OF HEAD AND SHOULDERS TO THE METRO COMPANY FOR TWENTY FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS I LOVE YOU DEAREST GIRL

SCOTT

Notes:

1 Made as The Chorus Girl's Romance by Metro Pictures (1920).

42. TO SCOTT

[February 1920]

AL, 6 pp.; Correspondence.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

Darling Heart, our fairy tale is almost ended, and we’re going to marry and live happily ever afterward just like the princess in her tower who worried you so much—and made me so very cross by her constant recurrence—I’m so sorry for all the times I’ve been mean and hateful—for all the miserable minutes I’ve caused you when we could have been so happy. You deserve so much—so very much—

I think our life together will be like these last four days—and I do want to marry you—even if you do think I “dread” it—I wish you hadn’t said that—I’m not afraid of anything. To be afraid a person has either to be a coward or very great and big. I am neither. Besides, I know you can take much better care of me than I can, and I’ll always be very, very happy with you—except sometimes when we engage in our weekly debates—and even then I rather enjoy myself. I like being very calm and masterful, while you become emotional and sulky. I don’t care whether you think so or not—I do.

There are 3 more pictures I unearthed from a heap of debris under my bed. Our honored mother had disposed of ’em for reasons of her own, but personally I like the attitude of my emaciated limbs, so I solict your approval. Only I waxed artistic, and ruined one.

Sweetheart—I miss you so—I love you so—and next time I’m going back with you—I’m absolutely nothing without you—Just the doll that I should have been born. You’re a necessity and a luxury and a darling, precious lover—and you’re going to be a husband to your wife—

Notes:

48. Nancy Milford dates this letter March 1920 and believes that it was the last letter Zelda wrote to Scott before their marriage. Scott’s biographer Matthew J. Bruccoli, however, believes that the letter was written earlier in February. The editors agree with the February date because Zelda’s writing “and next time I’m going back with you” indicates that Scott was still making trips to Montgomery.

1 During the early days of their engagement in 1919 Zelda Sayre continued to go out with other men, which elicited Fitzgerald's repeated comment that now he knew why princesses were locked in towers.

2 They had renewed their engagement during Fitzgerald's recent visits to Montgomery.

43. TO SCOTT

[February 1920]

AL, 8 pp.; Correspondence.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

O, Scott, its so be-au-ti-ful—and the back’s just as pretty as the front. I think maybe I like it a little better, and I’ve turned it over four hundred times to see “from Scott to Zelda.” I try to feel so rich and fine but I’m so tickled I can’t feel any way but happy—happy enough to bubble completely over and flow away into a sweet-smelling nothing. And I’ve decided, like I do every night before I go to sleep, that you’re the dearest, dearest man on earth and that I love you even more than this delicious little thing ticking on my wrist.

Mamma came in with the package, and I thought maybe it might interest her to know, so she sat on the edge of the bed while I told her we were going to marry each other pretty soon. She wants me to come to New York, because she says you’d like to do it in St. Patrick’s. Now that she knows, everything seems mighty definite and nice; and I’m not a bit scared or shaky—What I dreaded most was telling her—somehow I just didn’t think I could—Both of us are very splashy vivid pictures, those kind with the details left out, but I know our colors will blend, and I think we’ll look very well hanging beside each other in the gallery of life [This is not just another one of my “subterranean river” thoughts]

And I love you so terribly that I’m going to read “McTeague”—but you may have to marry a corpse when I finish. It certainly makes a miserable start—I don’t see how any girl could be pretty with her front teeth lost in action, and besides, it outrages my sense of delicacy to have him violently proposing when she’s got one of those nasty rubber things on her face. All authors who want to make things true to life make them smell bad—like McTeague’s room—and that’s my most sensitive sense. I do hope you’ll never be a realist—one of those kind that thinks being ugly is being forceful—

When my wedding’s going to be, write to me again—and if you’d rather have me come up there I will—I told Mamma I might just come and surprise you, but she said you mightn’t like to be surprised about “your own wedding”—I rather think it’s my wedding—

“Till Death do us part”

Notes:

49. When Scott sold “Head and Shoulders” to the movies for $2,500, he sent Zelda a $600 platinum and diamond watch.

50. These brackets were supplied by Zelda.

51. In McTeague (1899), a novel by Frank Norris, who belonged to the literary school of naturalism, the protagonist is a dentist smitten by a young woman named Trina, whose gaping smile he corrects with bridges and crowns, after which he marries Trina, then murders her. Zelda apparently found Norris’s naturalism so repulsive as to be amusing.

44. TO SCOTT

[March 1920]

ALS, 4 pp.; Correspondence.

[Montgomery, Alabama]

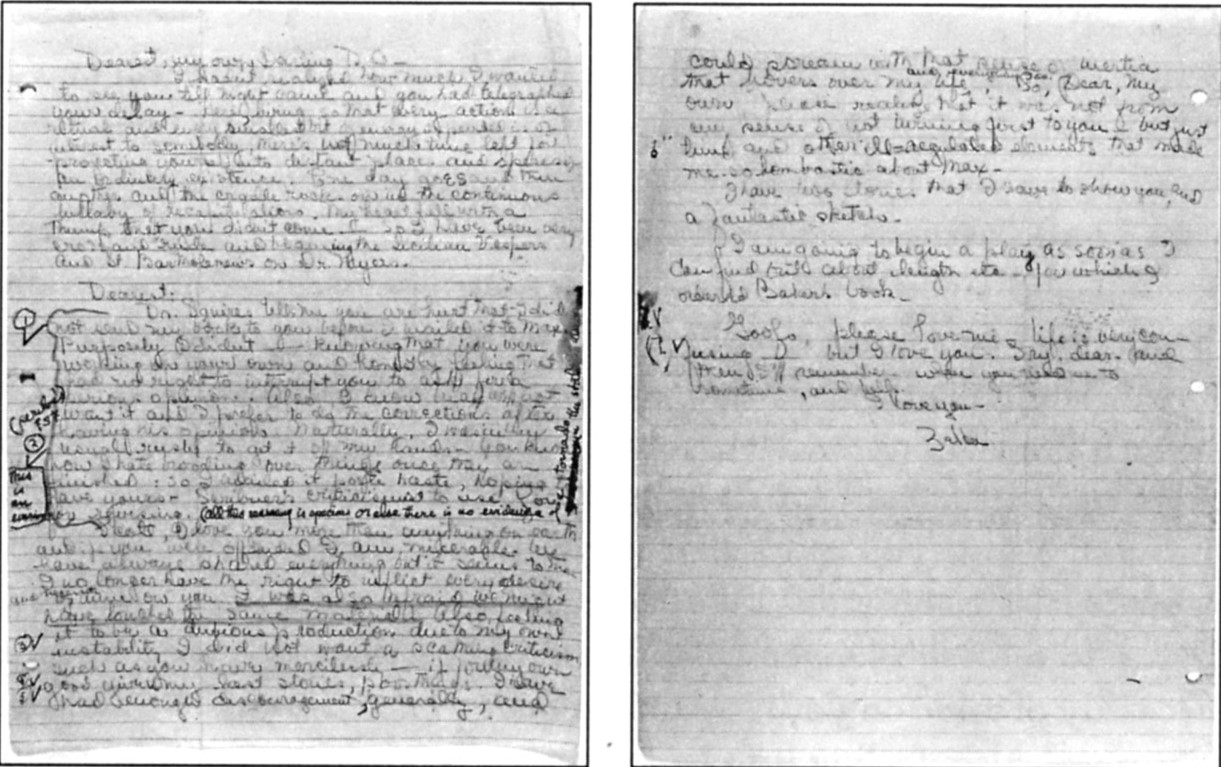

Dearest—

I wanted to for your sake, because I know what a mess I’m making and how inconvenient it’s all going to be—but I simply can’t and won’t take those awful pills—so I’ve thrown them away. I’d rather take carbolic acid. You see, as long as I feel that I had the right, I don’t much mind what happens—and besides, I’d rather have a whole family than sacrifice my self-respect. They just seem to place everything on the wrong basis—and I’d feel like a damned whore if I took even one, so you’ll try to understand, please Scott—and do what you think best—but don’t do anything till we know because God—or something—has always made things right, and maybe this will be.

I love you, Darling Scott, and you love me, and we can be thankful for that anyway—

Thanks for the book—I don’t like it—

Zelda Sayre

Notes:

52. Zelda mistakenly believed that she might be pregnant.

45. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

[PRI]NCETON NJ 1117AM MAR 23 1920

MISS ZELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

GOOD MORNING ZELDA DEAR YOU KNOW I DO

SCOTT

46. TO ZELDA

[March 1920]

Wire. Scrapbook

[Princeton, New Jersey]

MISS ZELDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA DEAR YOUR LETTER JUST CAME I HAD COUNTED ON YOUR LEAVING MONTGOMERY ON THE THIRTIETH OF THIS MONTH BUT IF YOU ARE READY TO COME EARLIER SAY ON THE TWENTIETH WIRE ME TODAY YOU KNOW I WANT YOU ALL THE TIME DEAREST GIRL YOUR PICTURE HAS NOT COME AM WRITING

47. TO ZELDA

[March 1920]

Wire. Scrapbook

PRINCETON NJ 1042A 17

MISS TILDA SAYRE

SIX PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

THE PICTURE IS LOVELY AND SO ARE YOU DARLING

48. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook

PRINCETON NJ MARCH 28 1920

MISS ZELDA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALABAMA YOUR TELEGRAM CAME TONIGHT I HAVE TAKEN ROOMS AT THE BALTIMORE [BILTMORE?] AND WILL EXPECT YOU FRIDAY OR SATURDAY WIRE ME EXACTLY WHEN WILL CALL TOOTSIE TOMORROW MORNING BOOK SELLING ALL MY LOVE

SCOTT

Notes:

53. This Side of Paradise was published on March 26, 1920.

49. TO ZELDA

Wire. Scrapbook; Correspondence.

[Princeton] NJ

NEWYORK NY MAR 30 1920

MISS TILLA SAYRE

6 PLEASANT AVE MONTGOMERY ALA

TALKED WITH JOHN PALMER AND ROSALIND AND WE THINK BEST TO GET MARRIED SATURDAY NOON WE WILL BE AWFULLY NERVOUS UNTIL IT IS OVER AND WOULD GET NO REST BY WAITING UNTIL MONDAY FIRST EDITION OF THE BOOK IS SOLD OUT ADDRESS COTTAGE UNTIL THURSDAY AND SCRIBNERS AFTER THAT

LOVE

SCOTT

Notes:

54. John Palmer (Clothilde’s husband) and Rosalind (Zelda’s sister) apparently helped Scott with the last-minute wedding arrangements. Zelda’s other sister, Marjorie, accompanied her to New York for the wedding. Neither Scott’s nor Zelda’s parents attended. The small wedding party consisted of Zelda’s three sisters; her brothers-in-law, Newman Smith and John Palmer; and Scott’s best man, Ludlow Fowler, his friend from Princeton. Scott was so nervous he began the ceremony before John and Clothilde arrived.

John Palmer was married to Zelda's sister Clothilde; Rosalind was another sister.

PART II

The Years Together: 1920–1929

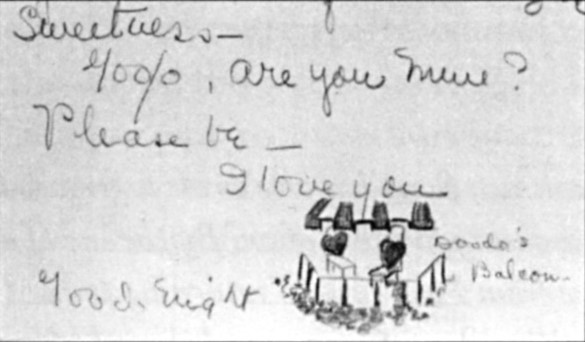

50. TO SCOTT

[September 1920]

ALS, 2 pp.

[Westport, Connecticut]

I look down the tracks and see you coming—and out of every haze + mist your darling rumpled trousers are hurrying to me—Without you, dearest dearest I couldn’t see or hear or feel or think—or live—I love you so and I’m never in all our lives going to let us be apart another night. It’s like begging for mercy of a storm or killing Beauty or growing old, without you. I want to kiss you so—and in the back where your dear hair starts and your chest—I love you—and I cant tell you how much—To think that I’ll die without your knowing— Goofo, you’ve got to try [to] feel how much I do—how inanimate I am when you’re gone—I can’t even hate these damnable people— nobodys got any right to live but us—and they’re dirtying up our world and I can’t hate them because I want you so—Come Quick— Come Quick to me—I could never do without you if you hated me and were covered with sores like a leper—if you ran away with another woman and starved me and beat me—I still would want you I know—

Lover, Lover, Darling—

Your Wife

51. TO ZELDA

[Summer 1930]

AL (draft), 7 pp.; Correspondence.

[Paris or Lausanne]

Written with Zelda gone to the Clinque

I know this then—that those day when we came up from the south, from Capri, were among my happiest—but you were sick and the happiness was not in the home.

I had been unhappy for a long time then—when my play failed a year and a half before, when I worked so hard for a year[,] twelve stories and novel and four articles in that time with no one believing in me and no one to see except you + before the end your heart betraying me and then I was really alone with no one I liked. In Rome we were dismal and was still working proof and three more stories and in Capri you were sick and there seemed to be nothing left of happiness in the world anywhere I looked.

Then we came to Paris and suddenly I reallized that it hadn’t all been in vain. I was a success—the biggest one in my profession— everybody admired me and I was proud I’d done such a good thing. I met Gerald and Sara who took us for friends now and Ernest who was an equeal and my kind of an idealist. I got drunk with him on the Left Bank in careless cafes and drank with Sara and Gerald in their garden in St Cloud but you were endlessly sick and at home everything was unhappy. We went to Antibes and I was happy but you were sick still and all that fall and that winter and spring at the cure and I was alone all the time and I had to get drunk before I could leave you so sick and not care and I was only happy a little while before I got too drunk. Afterwards there were all the usuall penalties for being drunk.

Finally you got well in Juan-les-Pins and a lot of money came in and I made [one] of those mistakes literary men make—I thought I was a man of the world—that everybody liked me and admired me for myself but I only liked a few people like Ernest and Charlie McArthur and Gerald and Sara who were my peers. Time goes bye fast in those moods and nothing is ever done. I thought then that things came easily—I forgot how I’d dragged the great Gatsby out of the pit of my stomach in a time of misery. I woke up in Hollywood no longer my egotistic, certain self but a mixture of Ernest in fine clothes and Gerald with a career—and Charlie McArthur with a past. Anybody that could make me believe that, like Lois Moran did, was precious to me.

Ellerslie, the polo people, Mrs. Chanler the party for Cecelia were all attempts to make up from without for being undernourished now from within. Anything to be liked, to be reassured not that I was a man of a little genius but that I was a great man of the world. At the same time I knew it was nonsense—the part of me that knew it was nonsense brought us to the Rue Vaugirard.

But now you had gone into yourself just as I had four years before in St. Raphael—and there were all the consequences of bad appartments through your lack of patience (“Well, if you want a better appartment why don’t you make some money”) bad servants, through your indifference (“Well, if you don’t like her why don’t you send Scotty away to school”) Your dislike for Vidor, your indifference to Joyce I understood—share your incessant entheusiasm and absorbtion in the ballet I could not. Somewhere in there I had a sense of being exploited, not by you but by something I resented terribly no happiness. Certainly less than there had ever been at home—you were a phantom washing clothes, talking French bromides with Lucien or Del Plangue—I remember desolate trips to Versaille to Rhiems, to LaBaule undertaken in sheer weariness of home. I remember wondering why I kept working to pay the bills of this desolate menage. I had evolved. In despair I went from the extreme of isolation, which is to say isolation with Mlle Delplangue, or the Ritz Bar where I got back my self esteem for half an hour, often with someone I had hardly ever seen before. In the evenings sometimes you and I rode to the Bois in a cab—after awhile I preferred to go to Cafe de Lilas and sit there alone remembering what a happy time I had had there with Ernest, Hadley, Dorothy Parker + Benchley two years before. During all this time, remember I didn’t blame anyone but myself. I complained when the house got unbearable but after all I was not John Peale Bishop—I was paying for it with work, that I passionately hated and found more and more diffi-cult to do. The novel was like a dream, daily farther and farther away.

Ellerslie was better and worse. Unhappiness is less accute when one lives with a certain sober dignity but the financial strain was too much. Between Sept when we left Paris and March when we reached Nice we were living at the rate of forty thousand a year.

But somehow I felt happier. Another Spring—I would see Ernest whom I had launched, Gerald + Sarah who through my agency had been able to try the movies. At least life would [seem] less drab; there would be parties with people who offered something, conversations with people with something to say. Later swimming and getting tanned and young and being near the sea.

It worked out beautifully didn’t it. Gerald and Sara didn’t see us. Ernest and I met but it was a more irritable Ernest, apprehensively telling me his whereabouts lest I come in on them tight and endanger his lease. The discovery that half a dozen people were familiars there didn’t help my self esteem. By the time we reached the beautiful Rivierra I had developed such an inferiority complex that I couldn’t face anyone unless I was tight. I worked there too, though, and the unusual combination exploded my lungs.

You were gone now—I scarcely remember you that summer. You were simply one of all the people who disliked me or were indifferent to me. I didn’t like to think of you.—You didn’t need me and it was easier to talk to or rather at Madame Bellois and keep full of wine. I was grateful when you came with me to the Doctors one afternoon but after we’d been a week in Paris and I didn’t try any more about living or dieing. Things were always the same. The appartments that were rotten, the maids that stank—the ballet before my eyes, spoiling a story to take the Troubetskoys to dinner, poisening a trip to Africa. You were going crazy and calling it genius—I was going to ruin and calling it anything that came to hand. And I think everyone far enough away to see us outside of our glib presentations of ourselves guessed at your almost meglomaniacal selfishness and my insane indulgence in drink. Toward the end nothing much mattered. The nearest I ever came to leaving you was when you told me you thot I was a fairy in the Rue Palatine but now whatever you said aroused a sort of detached pity for you. For all your superior observation and your harder intelligence I have a faculty of guessing right, without evidence even with a certain wonder as to why and whence that mental short cut came. I wish the Beautiful and Damned had been a maturely written book because it was all true. We ruined ourselves—I have never honestly thought that we ruined each other

Notes:

1. Scott may never have sent this letter.

2. Charles MacArthur, American playwright and, later, screenwriter and husband of actress Helen Hayes. Scott had met and caroused with MacArthur on the Riviera during the summer of 1926.

3. Mrs. Winthrop Chanler, a wealthy society matron whom Scott had first met when he was a young man.

4. Scott’s second cousin, daughter of his cousin Cecilia Taylor.

5. King Vidor, Hollywood movie director, whom Scott met in Paris in the summer of 1928 and with whom he briefly planned to make a movie.

6. Mademoiselle Delplangue was Scottie’s governess.

7. Hadley Richardson, Hemingway’s first wife.

8. Scott introduced King Vidor to Gerald Murphy and the two later collaborated on the film Hallelujah! (1929), Hollywood’s first all-black movie.

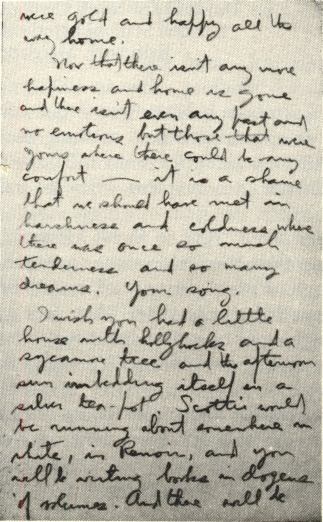

52. TO SCOTT

[September(?) 1930]

AL, 42 pp., on stationery embossed ZELDA at top center; Correspondence.

[Prangins Clinic, Nyon, Switzerland]

Dear Scott:

I have just written to Newman to come here to me. You say that you have been thinking of the past. The weeks since I haven’t slept more than three or four hours, swathed in bandages sick and unable to read so have I.

There was: