Beautiful Fools

by R. Clifton Spargo

4

THE WINDS, STRONGER BY THE MINUTE, BLEW OUT ONTO THE GULF. Several times Zelda reached up to secure the lavender cloche atop her head, its floral bow tossed frantically by the gusts. Scott walked to her left, near the curb, her gloved hand resting on the cuff of his coat, their conversation aimless yet stilted. Despite the constant flow of correspondence between them these past few years, he existed now on the perimeter of her everyday life, and sometimes he wondered whether he had the right to be admitted to the inner workings of her mind.

“Tell me again,” he said, “about the painting lessons in Florida, the time with Dr. Carroll.”

Two months ago while in Sarasota under the hospital’s care, she’d taken a life drawing class at the Ringling School of Art, another in costume design.

“Dr. Carroll thought it odd that I could be such an accomplished painter, his words not mine,” she said, “someone who has held exhibitions, sold paintings, and been reviewed in the New York Times, without the benefit of any real training.”

“Some people are born with natural talent.”

“That’s what Dr. Carroll said, but I know better. So many of my talents went untrained for so long. My natural creativity is highly undisciplined.”

It was an unmistakable reference to her thwarted career as a dancer, for which she’d started too late, for which in an effort to compensate for her belatedness she’d trained too fast and frantically. Scott didn’t wish to take up the topic.

“Some of the women from the Highland must have strolled here early evenings in January when they visited,” she said, alluding to the trip for which this vacation was a substitute.

“Do you wish you’d come with them,” he said, “instead of coming with me?”

“Scott, don’t ask that. You know I’d rather be with you than with anyone.”

She stopped to rest against the seawall, leaning onto its wide-girthed bulk and into a purpling sky, the winds warm off the ocean, the moon and the city lights sparkling along the water far out into the straits where everything disappeared into black. She listened to the break of the waves, slapping on coastal rocks, then receding in a gentle wash.

“I feel sorry for the other women sometimes,” she said. “They must do everything for themselves, must make sense of small things such as a walk on a promenade entirely on their own. I always have you to help me sift through my thoughts and memories.”

She rarely spoke of her fellow patients as individuals. She spoke of exercises executed in groups, of her superiority to the women in sporting activities, of their prevailing opinions on films and books, but she cited none of them singularly as you might speak of a friend. Whenever he imagined her participating in some activity, she was stolid and alone. Always she had preferred men to women, and on the occasions when she broke from this basic pattern, her affections turned to crushes, passionate in their intensity. Madame Egorova, her former ballet instructor, was only the most illustrative, catastrophic example. Zelda’s obsessive desire to please her had led to the ascetic diet, the unceasing practices, and the insomnia that precipitated her first breakdown.

“You think that’s petty of me,” Zelda asked.

“What?”

“You think it petty, or perhaps egoistical, of me.”

“They’re hardly the same thing.”

“Do you think it egoistical of me to see myself as better than the other patients?”

“I didn’t take you to be saying that at all.”

It was odd how easily they fell into familiarity, and yet there was so much that went unsaid, so much of everyday worry they no longer shared. She asked about Hollywood, when his contract was up for renewal, when he would be assigned to a new film, and he said to himself, She’s like a bloodhound, always on the scent of my troubles. He avoided any mention of his failure to be renewed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, promising there was no need to worry, work would soon come his way, downplaying the drama of his circumstances because, after all, there was nothing she could do to help and her worries only compounded his own. There was no one in whom he might more naturally have confided the cumulative injustice of this past year’s string of professional heartbreaks, and yet he couldn’t risk it for fear of damaging her fragile psyche. Also, he had entrusted that privilege to another woman. Sheilah, in the role of confidante and booster, was entitled to hear his grievances, his increasingly humbler hopes. As someone who trafficked in the industry’s secrets, sharing them with the public in her syndicated “Hollywood Today” column, she could offer consolations based on practical knowledge of his trade. And he was sometimes able to return the favor, repaying her with writerly advice, helping her work out an idea for a column.

“Are you thinking of her?”

“Excuse me,” he said, stumbling, trying to remember where he’d left off. “Weren’t we talking about Dr. Carroll?”

“That was a long time ago.”

“Also about the women at the hospital, whether you were petty?”

“Well, I don’t care to repeat myself just now.”

“If you were trying to bring up our daughter—”

“I wasn’t.”

“I wouldn’t mind speaking about our need to form a united front in conveying to Scottie the seriousness of her situation. How she must make her way in the world after Vassar, without resources to fall back on. How she must prepare to live on her own and for herself, realistically, beginning now while there’s time.”

“So she doesn’t end up a young fool without a plan, much like her mother?”

“Or her father,” he said equably.

“Scott, you must remember she’s only a child, seventeen.”

“She doesn’t have much of a safety net.”

“Don’t make me worry for her,” Zelda said with a hint of panic in her voice. “Not here, not now, not yet.”

Clearly, Zelda had intuited his reason for changing the topic. Her pride, however, would keep her from pursuing the original question. It was altogether possible she had never heard the name Sheilah Graham voiced by another person, but still Zelda could be counted on to sense when there was someone new in his life, some usurper eager to take up as much room as his imagination would allow her.

Ahead of them the promenade opened onto a plaza, people huddled along the seawall. “How marvelous,” Zelda exclaimed. “If I lived in this city, I would come here every night.” A shabbily dressed young man with neatly cropped, kinked hair drew near. “You are Americanos, no?” He walked beside them, slowing their pace, soon joined by a woman as he explained, “Es mi madre,” repeating the phrase several times, though Scott couldn’t figure out why a young man in his early twenties was accompanied by his mother at this hour of the night. He spoke of the United States, mixing English and Spanish, dashing off complex sentences in his native tongue. Whenever they tried to negotiate a difficult phrase, Scott cringing at his own incompetence in Spanish, Zelda took the lead in contriving pacts of compromised knowledge by picking up Latin roots in ways he couldn’t. Or by repeating cognates with the syllables accented in the wrong place, a la the rhythms of French. Or, still more crudely, by pantomiming objects to match the words. The system had its limits, but through it they figured out that the young man and his mother resided in one of the barrios within the Old City. Infinitely patient in his desire to be understood, he proposed many places the Americans might visit, then issued an invitation that neither Scott nor Zelda could decipher, though, clearly, it involved listening to music.

“He wants to take you out on the town, presumably at your expense,” a man interjected. Scott turned to find himself face to face with Mateo Cardona, the girl Yonaidys at his side. He didn’t believe for a second that the meeting was by chance.

“Scott, it is good to see you,” Mateo said, looking from him to his wife. “Zelda Fitzgerald, I hope you enjoyed your dinner.”

Zelda started at the mention of her name, leaning in to whisper something Scott couldn’t hear, even as he replied, automatically, under his breath, “It’s okay, Zelda.”

“Senora Fitzgerald,” the girl now chimed in, “we believe you, how you say, sueno—”

“Sleep,” Mateo said.

“Yes, sleep,” Yonaidys said, echoing Mateo, “until there was no night? No time for revel, revel, what is—”

“Revels,” Scott said.

“Si,” said the young girl, whom Scott now saw through Zelda’s eyes: the hem of her dress hanging slightly, her white shoes scuffed with dirt. She seemed woefully deficient by contrast to the elegantly dressed man at her side.

The young man, perceiving that he and his mother were being supplanted by this new couple, said his goodbyes, but not before inviting the Fitzgeralds to visit his home, rolling his finger several times before his mouth in an effort to encourage Mateo to translate as he explained that the Americans had expressed interest in joining him for dinner.

Scott asked, “Was he inviting us to visit him?”

“Very good,” Mateo said easily. “I’ve made a mental note of the directions and would be happy to escort you tomorrow or another day, if you wish to see how the other half lives. But I recommend visiting during the daytime.”

“I hadn’t made up my mind one way or the other,” Scott said, resenting Mateo’s paternalistic tone, “but I certainly wouldn’t have taken my wife to an unknown, most likely impoverished section of the city at night.”

“That is wise,” Mateo congratulated him. “So will you join us on our walk? I am far better suited to introduce you to our fashionable city and its history and culture.”

Scott understood there was no easy way to extricate himself a second time from Mateo’s company.

“We’re headed for a drink,” Scott said.

“Where?”

“Maybe Sloppy Joe’s.”

“?No lo permita Dios!” Yonaidys cried.

“She is offended on behalf of God and Cuba,” Mateo explained. “That place is strictly for Americans. Let us escort you to a worthy Cuban establishment.”

So they followed the charismatic Cuban, who kept two steps ahead at all times, walking sideways now and then to direct Zelda’s attention to vistas of the city. He stopped them before a monument to the USS Maine, sunk in 1898, then turned them toward the center of town, the salt air thinning, the sound of waves against the seawall receding. They walked the Prado, a tree-lined, terrazzo-floored promenade dense with restaurants, hotels, galleries, and music halls, but also with musicians, dancers, prostitutes, and street peddlers of all stripes.

“Ignore them, that is all.” Senor Cardona referred generally to the undesirables.

“So you will know what you are missing,” he said moments later, cupping Zelda’s arm, directing her vision down the block to the crowds overflowing from under the arcade of an Italianate three-storied building, its flattened arches and distinctive cornice shining coral pink in the nighttime sky. “It is the place we must avoid, the famous Sloppy Joe’s.”

“En este direccion, por favor,” the girl said cheerfully, ending her long silence, motioning with her hand as if to hurry their escape from the tourists assembled there, and soon they bypassed several raucous bars packed with Cubans and foreigners.

Beyond the last of these their hosts turned them onto a narrow lane, halting before an establishment from which throbbed the sounds of rhythmic African music.

***

The girl began to chatter in Spanish and Zelda was exasperated. Who were these people? How could Scott know anything about them from an hour’s conversation in a hotel lobby? Had he given any thought to where they were, whether it was safe? Inside the bar there wasn’t a foreigner in sight. Mateo led them to a table with a view of the band, an eight-person ensemble—guitarist, four percussionists, two guys on horns, and singer—pumping out a sultry but high-energy modern music on a makeshift stage in the far corner, the song paced by the layered percussion. She felt summoned by the brightly clicking claves and steady two-tone beat of the woodblocks, by the diffuse shimmer of the large gourd keeping time with the rippling beat of a washboardlike wooden instrument. All around them blacks, mulattos, and a very few fair-skinned Spanish Cubans swayed and tapped their feet without paying attention to the band.

It was a juke joint, for all practical purposes, like one of the many seedy establishments strewn across her own Deep South and patronized exclusively by blacks, at which on any given night the pulsing music inspired dance, sultry liaisons, lovers’ quarrels, sometimes quarrels between rivals over the same lover. From the time she was a girl of twelve Zelda had been up for any adventure. She relished the jazz bars she and Scott had visited in Harlem in the early years after their marriage, but she never managed to get herself inside a Southern juke joint. It just wasn’t something white people did. Thrilled by the idea of listening to this Cuban cousin of jazz blues in an establishment her genteel parents would never have set foot in, thrilled also by the sensual progression of the song, she let the pulsingly metrical music roll through her like nervous excitement, listening for space within the melody, deep within the beat, attempting to squeeze her way inside the song as if it were a crowded room.

“Your wife understands music,” Mateo said to Scott, but Zelda did not look up.

“She was once an accomplished dancer,” Scott said, and she heard her own thoughts, unvoiced, Until my art disrupted the routine of your writer’s life and you put a stop to it, but even as she phrased the words, she realized she could no longer feel the bitterness they once inspired. Enjoying the music, she instructed herself: He has done his best and fought battles for you, losing many, but never casually.

Mateo bought drinks for the group and Zelda absently sipped hers without tasting it, not wanting to lose the thread of the song. Scott was saying something, but she waved him off. Her body in motion on the inside, she could project images of herself that corresponded to the music. For every arrangement of notes built on intervals and rhythm there is a motion through which the body might objectify it in dance. In listening for that form, Zelda released herself from the strictures of social etiquette, let go of the night, her rough sleep, and the distress of traveling with an alcohol-wearied Scott. Let go also of waking alone in a hotel room, not knowing where he was or how long he’d been away or if he would return. Music is healing, she might have said under her breath, knowing she would give anything, after all it had cost her, for one last chance at the ballet. So what if devotion to her art unfit her for the world. Once you knew what it was to live inside a song, and allow your body to become its instrument, everything else in life was disappointing.

“Zelda,” Scott was whispering to her, “you’re being antisocial. Are you angry with me?”

“I’m having a good time,” she said, charmed by the song’s percussive drive, “and I know you’ll watch out for me, I have absolute confidence in you.”

How strange it was that she of all people had married a man with no ear for music. If she were to stop and ask Scott to describe how it made him feel, whether he could hear the intervals, the structure of memory and anticipation by which any song lived, he would look at her with admiring annoyance. He might dismiss her as a mystic, worse yet a Dionysian. And so what if she was. Did he think his the only true art? He couldn’t hear what she heard in song, the echo of meaninglessness, the place inside it where we all become nothing. About music he was merely sentimental, the way he was also about women. All he heard were the lyrics in their scant ephemerality, how they scuttled like mice across the surface of the song, extrapolating on the rhythm. He couldn’t understand that the words were beats and syllabic notes and varying lengths of breath, and if she were to jumble them in a babble of consonants and vowels, all that really mattered was that she could unscramble them well enough to find usable vowels through which to hold open the notes, also some punchy consonants with which to scat and propel the melody forward so it didn’t succumb to the ecstatic drive of the percussion.

She moved closer to Scott, wrapping her palm on his forearm, squeezing it. She listened closely to the song, how different this relentlessly percussive music was from jazz. Scott, listening only to Mateo, nevertheless tilted his head to smile at her.

Could he hear it too? she asked in a whisper, and Scott rotated to stare at her as though reproving an eccentric child.

“Speak plainly, Zelda. We can’t afford mystery this time around. It’s too risky.”

“I wasn’t being mysterious, only musical.”

From across the table she could feel Mateo, pretending to look away but listening to every word, studying the two of them out of the corner of his eye.

“Is this about your dancing?” Scott asked.

“Oh, never mind,” she said, “and don’t start accusing me of bringing up things I’ve long ago stopped bringing up. Not my fault if you still feel guilty about squelching my dance amb—”

“Zelda, stop,” he said. “Not while we’re out with people.”

“We don’t know these people,” she sighed, “and, besides, I’m done now. As a matter of fact, I have to use the bathroom. Can you ask them where it is?”

Mateo proposed that Yonaidys escort Zelda. To which Zelda replied, without so much as glancing at the Cuban, “Scott, I don’t expect to be treated like some patient in an asylum, watched at every minute.”

“No hay problema,” Yonaidys said. “Yo tambien, I have need also of el cuarto de bano.”

“Zelda,” Scott scolded, “she is only being courteous.”

So Zelda waited as Mateo stood clear of the table to let Yonaidys pass, and soon the lithe young woman was escorting her to the rear of the bar, beyond the band, now driving the song to its end with cadent harmonies layered over the percussion, the crescendo rolling forward into the crowd like a storm front until even the portion of the room it hadn’t yet reached was sweltering, stifling, and Zelda suddenly wished she were headed out of this bar rather than into its bowels.

***

“She is nervous, no?” Mateo asked. “Your wife is made nervous by this place to which we have escorted her?”

Scott shifted uneasily. He could no longer see Zelda through the throngs at the rear of the room.

Mateo was preparing himself to make a pitch of some sort, everything he said inclining toward greater consequence. Wending through banal chatter, he told Scott about his acquaintance with the bartender, about the bar’s reputation for playing the best African music in the city, about his practice of bringing here only those Americans who could appreciate cultures other than their own. He’d known Scott for such a person right away. Scott rested an elbow on the edge of the table, propping his chin on his thumb and caressing the thin two-day stubble along his jawline.

Mateo, his intentions seemingly as aimless as his manner, asked for Scott’s opinions on baseball, wondering whether he was a fanatic of the great American sport, also the national pastime of Cuba. Mateo had attended games of the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers, he had witnessed firsthand the impressive feats of the New York Yankees, but he believed in the prowess of his own countrymen. The best among the Cuban baseballers, men such as Jose de la Caridad Mendez, Joseito Munoz, and Cristobal Torriente, were as grand as Cobb, Ruth, and Gehrig. Though no expert on the sport, Scott had spent countless hours in the company of famed sportswriter Ring Lardner, long evenings squandered on Ring’s porch in Great Neck, lapping up his booze and his stories about the greatest of pastimes, many of which ended with his drinking ballplayers under the table while instructing them on the art of a game they played expertly but appreciated far less than he. Ring had bestowed on Scott enough knowledge to make him capable of comparing Mateo’s present chatter, for instance, to the tactics of a clever pitcher working a batter with off-speed junk, tossing slow curves and change-ups early in the count in order to sneak the fastball by a few pitches later.

Shifting gears, Mateo made mention of a new project in development, a hotel here in Havana. The developer was a friend. If Scott had ever thought of investing in Cuba, now was an ideal time to do so. Mateo could personally assure him that Americans were making money hand over fist in Cuban real estate, in hotels, in bars and jazz speakeasies, in beach properties. Scott should think about it. Mateo would be happy to set up a meeting any time over the next few days, an informal talk with the magnate, or one of his associates, so that Scott might assess such a nice opportunity. Scott smiled grimly. Inside him was an echo of laughter, sturdy and nihilistic. He thinks I have money, Scott said to himself. He thinks because I was on the cover of a few magazines and he can remember my novels, probably owned This Side of Paradise without reading it, because I should have saved and invested or because my books and stories will have continued to sell or because my wife so far as he knows never broke down and spent the last decade in expensive institutions, draining the dregs of her desperate soul, costing every last penny we had and then some, so much that I had to go to Hollywood and whore myself; he thinks because I will have stored up against the prospect of just such a terrible future and not spent money liberally in my youth; he thinks for all these reasons—and because I’m here with my fine American wife in Havana, mingling with the well-to-do—that I have the funds to invest in some cockamamy Caribbean venture of which I have no way of assessing the legitimacy.

Scott didn’t answer Mateo. Several minutes of conversational calm ensued, each man pretending to listen to the band while scanning the rear of the establishment for his companion.

Just then Scott spotted Zelda dashing into the crowd, something awry in her expression as she leaned a forearm into the back of one person after another. Men and women alike wheeled about, prepared to protest but mostly failing to do so, maybe because they recognized the desperation on her face, maybe because they made allowances for esoteric behavior from a lily-white foreigner so obviously out of place. Yonaidys followed in Zelda’s wake, slowing to speak with people she had jostled, offering excuses for the American. “Is something wrong?” Mateo asked, as if Scott could read his wife’s mind from across the room. It was possible someone had threatened her, or leered at her, or made unwelcome advances. It could have been almost anything. Halfway to him, Zelda stalled in the densest portion of the crowd, the band no longer playing, the club’s patrons amassed in a thick swarm between the stage and the bar as she tried to shove through them. A mulatto nearly as fair as Mateo, who wore dark hair streaked with brilliantine and a light-blue jacket, whirled in place shouting curses above the milling masses. He dropped his voice somewhat when he saw that he had been denouncing a woman but nevertheless continued his tirade for the benefit of those immediately surrounding him.

Mateo caught the attention of a dark-skinned man at a nearby table, indicating with a slight nod that he should intervene. The young man, who wore a white guayabera with a camp collar and stood several feet beyond Zelda, shouldered the two men who were in her path, and again she slanted toward Scott, slipping through the clustered people at the center of the bar. The next thing he knew, Zelda stood beside him, whispering into the side of his head, teeth clenched, voice gruff, her sentences impossible to hear. All he could make out was a phrase or two about her being unable to use the toilet. Meanwhile, he kept his eyes on the scene unfolding in her wake, whole sections of the crowd tossing one way, then another, as those siding with the man who’d cursed Zelda stole forward and those backing the black man who’d liberated her drove them back.

“Why, you ask,” she said. “Well, for one thing, it wasn’t clean enough.” She wanted him to ask what the second or third thing was, but he said nothing because he was studying the escalating violence and because he dreaded what she would say next; and if he could have put it off until later, he would have done so. Zelda’s ash-colored eyes bored into him. She was going to speak her mind whether he felt like hearing it or not. “And for another,” she said, “that crazy girl pulled a knife on me as we entered the bathroom.”

At first Scott didn’t believe her.

“You don’t believe me,” she said, then tried to explain, but still it didn’t make any sense, the details all jumbled. For a moment he feared she had come unhinged. Only later, as they lay awake in each other’s arms at the hotel in the early morning, did the source of her panic resolve itself into something like linear narrative, as he arranged the component parts neatly enough to see Mateo’s girl guiding Zelda into the bathroom and announcing, “I’ll stand guard,” or some such well-intended phrase that Zelda couldn’t hear for what it was, concentrated as she was on the fine steel blade the girl extracted from a case strapped to a garter inside her thigh. “She was offering to protect you, I am sure of it,” Scott told his wife by the gray morning light, and Zelda could no longer disagree. But that hadn’t seemed a likely explanation as she stepped into a stall with a flimsy door and broken clasp, her pelvis tightening, her bladder though full unable to release a drop of urine. No time for hindsight or clearheadedness, not while crouching in such a vulnerable pose, with a stranger outside your stall holding a long, thin blade. She had risen from the seat and rushed back to the table, shoving her way through the crowd, oblivious to the ire she provoked, to the curses, even to the handsome black man who had chivalrously thrown himself at her maligners—she must find Scott and tell him what had happened.

Amid the commotion of the bar he had tried to calm her, still not quite believing her, not finding any cause for alarm in Yonaidys’s actions in the bathroom, even if what his wife said was true. He praised the band, vowed that the bar was safe even as he shot nervous glances at Mateo, who surveyed the ongoing ruckus, which was gradually rolling forward, spilling into their corner of the establishment. Scott draped his arm over his wife’s shoulders, protectively, keeping her attention averted from the wildly tossing, listing swarm she had incited. Eventually, though, she must have heard the shouts and threats, or felt the pressure of Scott’s forearm holding her in place, because she shrugged her shoulders free of his hold and spun around and into the glint of a second knife, this one held less than a foot from her cheek by the black man in the guayabera. He was turned sideways in a defensive posture, his flank toward her, his right arm raised high and held away from his body, the blade dancing in his hand. The mulatto in the light-blue jacket who’d cursed her had squared off with the black man, also with knife in hand, the crowd spreading out in all directions, opening a circle around them.

It was impossible to say how long she stood in harm’s way. Scott, dulled by drink, reacted more slowly than he should have. Mateo stepped between Zelda and the melee even as the knife-wielding man nearest her lost his footing and tried to interrupt his fall with the hand in which he held the knife, whereupon the man in the blue jacket seized the opportunity to plunge a blade twice into the prone man’s chest, the white guayabera flowering like a rose as his body rolled toward Zelda and Mateo, blood splashing onto her dress.

She was still fixed on the injured man’s bleeding shirt when Scott pulled her stare to his own, her pupils empty and dilated. He cupped her clenched jaw in his hand so that she couldn’t peer down at the splatters on her pale-ivory dress, while Mateo, grasping her at the wrist, dragged them from the scene. She was whispering loudly under her breath, “I could kill you for this, I could just kill you,” and in case Scott hadn’t heard her the first time, “I could kill you for exposing me to this,” the tremolo of her voice succumbing to thoughts beyond her control.

Next: Chapter 5.

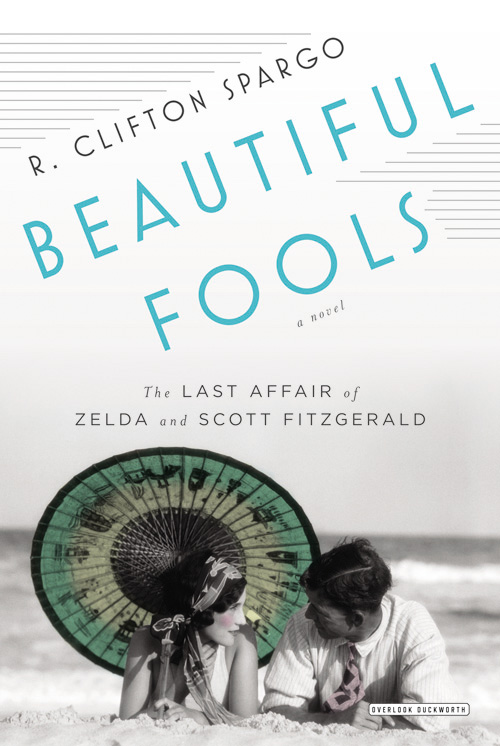

Published as Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald by R. Clifton Spargo (NY. Overlook Duckworth, 2013).