Beautiful Fools

by R. Clifton Spargo

5

ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF THE CITY THEY TOURED A DERELICT bullfighting ring, hardly recognizable as such, the high sun-bleached walls framing an arena long overrun with grass, the sport having disappeared from Cuba forty years ago under pressure from the United States. Their guide was an elderly man with sunburned skin, dark mustache set against a silver mane of hair, and a milky left eye, and he had never recovered from the death of his country’s once-beloved pastime. He could still conjure the bulls as they entered the ring, hides glistening like dark burnished wood in the sun, their tall-shouldered, majestically sculpted bodies arched and readied for battle, an entire stadium hanging on the grace of their incensed charge. Scott mentioned the bullfights in Morocco, attempting to introduce his experiences into the conversation, but the guide was too lost in his own longing for that which he would never again witness to hear his guest’s words.

“Scott, this is boring, I’m bored,” Zelda said. “I keep expecting Ernest to sprint round the corner in a cape, chasing a mythical bull, sticking it in the ass, saying, ‘I will overstand you, bull, or I am not the man.’”

“?No explico correctamente?” the guide asked, fearing he had erred in some way. “You and the senora wish me to explain again?”

“Zelda,” Scott said with exasperation.

“I don’t care, I’m awfully bored.”

“I understand English, senora,” the guide said, hurt by her rudeness. “I have been talking to you in English all day.”

“Yes, and mostly boring me in English all day.”

Scott grimaced, flashing her a look of gentle reproof.

“If he would only speak in Spanish,” she said, “I might imagine centuries of recondite history beneath his words, the dark Catholic soul of the Romance languages, all those monks mysteriously transcribing the thoughts of God in illuminated texts, taking dictation from Jews and other heretics stretched on the rack, the torture of bulls some kind of metaphor for—”

“Zelda, this must stop.”

He was not altogether against the humiliation of the guide, who was a surprise gift from Mateo Cardona and also something of a pompous ass. They’d come downstairs from Sunday brunch on the rooftop restaurant to find themselves summoned across the cavernous lobby, and at first Scott thought it must have something to do with the previous night, the end to which he began to replay in his head. First, the panicked urgency of getting Zelda out of the bar—he could remember saying as much to Mateo, in those very words, “I have to get her out of here,” and Mateo accepted Scott’s petition as though he were used to solving problems under circumstances more hazardous than these: “It is easily done. I will slip your wife out before the police arrive, here like this.” Scott hadn’t yet given any thought to the police, but no matter, Mateo took hold of Zelda’s wrist, beckoning Scott to follow, expertly guiding his guests through the huddling patrons and the onslaught of newcomers gathered at the entrance by the rumors of blood, most having been nowhere near the violence when it occurred. As yet no police. In this way, Mateo remarked, the Havana police were reliable. Nevertheless, they would soon arrive to comb the crowd for witnesses, some of whom might well remember a white American woman with high cheekbones and piercing eyes who stood only inches from the slain man, his blood splattered on her dress. Only then did it occur to Scott that Zelda was a material witness to a crime. Who knew what Cuban law called for, what the duties of a witness were in this city?

Might the police detain her for hours or days, demanding that she remain in the country until the trial? He foresaw the hassle, the need to borrow money, and if so, from whom? Over the past three years he’d paid down his debts but only at the cost of exhausting the goodwill of all his creditors: Max Perkins and Scribner’s; his agent Harold Ober; maybe even reliable Arnold Gingrich at Esquire. He could never turn to Sheilah for money, not after the way they’d parted. Of course, worse than any material debt was the possible cost to Zelda—who knew what toll reliving the crime over and over again might take on her?

They had slalomed through nighttime revelers on narrow streets, turning often, wending through a barrio ripe with the sweet, sickly smell of excrement and trash. Eventually Mateo drew them across an unevenly cobblestoned plaza at the far end of which stood a baroque cathedral in gray limestone with oddly asymmetrical bell towers. Along the colonnaded porticoes of the government buildings that flanked the square to the north and south, vagrants clustered around barrels of fire, their voices not quite carrying to the center of the plaza. “It is best to keep moving,” said Mateo, making sure Scott understood what was being done for him. At the far end of a street branching perpendicularly off the square, he could make out several men in uniforms, either soldiers or police, and immediately scanned his memory for details he had accumulated about this city’s recent history of coups, military dictatorships, and rogue paramilitary armies. “We must part here,” Mateo said, instructing Scott to continue three blocks down this same road past the uniformed men, until he reached Calle Obispo, there to take a left. Another four blocks, and the hotel would come into view. “Excuse me,” Scott interrupted. “Are those soldiers or policemen?” If stopped, Scott was to say he and his wife were returning from a romantic stroll along the Malecon. “Where?” Scott asked, and Mateo explained, “El Malecon, the seaside promenade on which I found you earlier. Tourists cannot get enough of it. And remember you enjoyed the ocean air, you lost track of the time, cutting back by way of Cathedral Square. You did not stop anywhere else. Entiendes?” Scott replied that he did and shook hands with his new friend, wondering how he could ever repay Mateo’s solicitude, worrying that his favors came at a price still to be named. Then he and Zelda walked hand in hand into the night, circumnavigating the soldiers who wore rifles slung halfway down their arms and inspected tourists through white clouds of cigar smoke without saying anything.

Being met this morning in the lobby of the Ambos Mundos by a guide they hadn’t hired, before they’d even decided what to do with their day, had made Scott uneasy. It felt too much like being spied on. But it wasn’t this fact alone that inspired his resentment of the silver-maned Cuban guide, who was, after all, hardly to be blamed for his paid-for meddlesomeness. No, it was the guide’s alternately officious and sycophantic manner. One minute he was bragging in petty bourgeois terms of hiring himself out to the highest bidder, the next slandering the Europeans who paid for his words but were indifferent to the wells of historical truth he could tap, preferring to be told nonsense (the guide used the word burradas, then translated it) about the passion of the Caribbean soul. Such were the results, he said, of a national economy dependent on the production of sugar, tobacco, and rum, on sweets and sin, on Americanos for whom Havana was an around-the-clock carnival; such, the wages of endless corruption. He spoke contemptuously of foreigners and his fellow countrymen alike.

Not only did he deserve to be put down for his airs, but maybe his cynicism merited a client such as Zelda. Still, it wasn’t wise to let go of the reins on her spite for too long.

“Zelda,” he said again, “please get yourself under control. Senor Famosa Garcia will complete the tour and then we will—”

“I do not wish to subject the senora,” the guide said, interrupting Scott, “to my observations if they do not please her, if they are too boring for her ears.”

“Well, that can’t be helped,” Scott said. In her unkindness Zelda was a picador, pricking the hide, enervating the soul, weakening the guide’s will to go on. “You’ve been paid well, and I’ll tip you later for having to put up with my wife’s cruel if precise wit. So let’s move on. Where to now?”

Already this morning the guide had driven them along the famous seaside promenade he judged an acceptable consequence of the brief American occupation of his country three decades ago, stopping at the far less acceptable monument erected in the 1920s to commemorate the sinking of the Maine, presuming they would wish to pay homage to their countrymen and the event that provoked the United States to declare war on Spain. He talked them through a visit to the Catedral San Cristobal de la Habana, which they’d briefly glimpsed the previous night, entertaining them with stories about the rivalry between Havana and Santo Domingo over two sets of bones, each reputed to be those of Christopher Columbus himself.

“It is up to you,” the guide said politely. “I am here to provide for you, of course.”

“One of the haciendas, then?” Scott suggested. “What other remnants of Spanish barbarism might we find entertaining, perhaps the defunct slaves’ quarters at one of the sugar mills?”

His refusal to soothe the guide’s vanity won Zelda’s gratitude, he could tell from the way she held herself, and it pleased him to be able to read her body language.

“Was I awful before?” she whispered when they were in the backseat of the car.

“No,” he said, only then pivoting to look at her, understanding that she meant much earlier—as in, the night before, when she hadn’t spoken as Scott pulled her gaze from the skirts of her dress, not a word of gratitude or curiosity as she was dragged through dank, shadowed streets by Mateo, not a whisper to Scott as he avoided the cigar-toting soldiers and delivered her to the lobby of the Ambos Mundos, riding the elevator to regain the safety of her room.

“You were frightened, that’s all. I’ve seen you far worse,” he said.

Even today she couldn’t remember anything of what had happened after the knife plunged into the man’s chest, the blood bright and effervescent on his white shirt. She asked her husband to tell her how they’d escaped the bar and made it back to the hotel, and as Scott described their exit remarked, “Oh, yes, I remember someone pulling at my arm.”

“We arrive at the hacienda of one of the great sugar mills of the old regime in Cuba in five minutes,” the guide said to them. All morning he had been estimating the time it took to go from one place to the next, and always it took longer than he said.

“Do you think anyone noticed anything?” Zelda whispered. “Maybe they could see the shadow of the crime, the way it clung to us, maybe they could see it my eyes. Do you think they will come for me?”

She spoke as though she didn’t want him to give her an honest answer. Sometimes he would have liked to ask her, “What are you capable of hearing today?” His impulse even after all these years was to confide in her, but he could never be certain whether she was up to the challenge of assessing her own well-being.

“For all they know, I could be the person who stabbed the man.”

“Don’t be preposterous, Zelda,” Scott said, reminding her again that they had done nothing wrong.

“Oh, I know,” she said. “Besides, I probably couldn’t tell them anything. I don’t remember looking at the man’s face, and if I did—”

Scott asked her to lower her voice.

“If I did, I hardly remember the color of his skin or the slope of his nose or the angle of his jaw. Still, do you think it’s right that we left without saying anything?”

In her mind she was a fugitive from last night’s violence, calculating how long she might have to stay on the run.

“We did nothing wrong,” Scott said again. Wrong place at the wrong time, that was all, but they were safe now.

She laid her left wrist on his lap, palm open and up, a gesture of invitation, and he stared down at her hand for a brief while, then clasped it in his, intertwining his fingers in hers.

“I didn’t mean what I said,” she whispered.

At first he couldn’t figure out what she was talking about.

“It’s a powerful feeling, I really can’t control it,” she said. The guide tossed off phrases from the front seat, but Scott ignored him. “It accumulates in me like bile, and I have to get it out of my system—you understand, don’t you? It doesn’t mean anything, not really. They were just words and you were in the way of them. I’m sorry you’re so often the one who is in the way of them.”

Now he understood and he heard the words again, fresh and sharp as if she’d just spoken them, I could kill you for this, suffering their malice for the first time.

“It’s only because you’re so good and loyal, and what’s your reward?” she said. “You always come back for me, even when no one else will. Even if everybody else is content to let me rot my days away in a madhouse.”

“Zelda, don’t.”

“Not you, you always come back.”

***

Not an insignificant portion of Mateo Cardona’s Sabbath had been devoted to making inquiries on behalf of his new acquaintances from the United States. He started by visiting the police station, letting it be known he was at the bar last night when the incident took place, since he was certain to be placed there sooner or later.

“Tell me, Mr. Cardona, what did you see?” asked the detective, who was well aware of the prestige of the Cardona name and whose courtesies were so exaggerated it might have been reasonable to infer hostility beneath them.

“If only I’d caught a better glimpse,” he replied. “It would make things simpler.”

“Indeed it would,” the detective said.

On any other night Mateo might have remained on the scene and taken charge, paying the two largest men he could find to seize the assailant and obtain the weapon. Of course, it all depended on the man—whether Mateo owed favors to any of his acquaintances or might procure their favor on credit. Mateo Cardona was by all accounts a pragmatic man. Even now, if the police were to apprehend a suspect and it was someone he agreed to identify, his reputation in the city was such that a prosecutor would have little trouble obtaining a conviction on his word alone. But then the assailant might remember seeing Mateo in the company of the two Americans who had riled him in the first place, and Scott had made it clear he didn’t want his wife involved. For the time being, there was more to be gained in covering for the Fitzgeralds.

What was it that made his actions from last night suspicious to the detective? Well, for one thing there was the mistake of leaving the scene, his judgment warped by the Americans, by his own inscrutable desire for the woman with her languorous eyes and thick pouting lips, also her amply curved figure, more like that of a Cubana than an Americana. Even today the image of her slow swaying inside the music pursued him, her motions sensual yet precise; and when he’d spotted the knife in the air, so close to Zelda’s face, the animal terror in her eyes, the color draining from her cheeks, he had known he must act. So he seized hold of her wrist as the man nearer Zelda slipped, his rival’s knife plunging into his chest as Scott rushed forward to obstruct her view while the wounded man writhed on the floor. The sensible thing to do was to stay and report what they had seen to the police. Not much could be made of Zelda’s role in the affair. Who would care if some white woman out of her element became claustrophobic and tried to shove her way through a crowd? Nevertheless, when Scott said, “We have to get her out of here,” Mateo took it as a command.

“Any Americans in the bar, by chance?”

Mateo ignored the question.

“So you didn’t see anything?”

“Nothing that can be of much use.”

“Then why are you here?”

“Duties of a citizen.”

“That would be a first,” the detective joked. It was impossible to tell whether he meant to accuse all of Havana’s citizens of a lax sense of duty or only the one sitting before him.

“Well, I am also an acquaintance of the victim’s family and of course I feel someone must pay for what happened. How is the victim this morning?”

“The family has not told you?”

“I have not spoken to his family since last night,” Mateo said.

“Let’s only say,” the detective replied, hesitating, most likely revealing less than he knew, “he has not regained consciousness.”

The detective asked in whose company Mateo spent the previous night.

“Only a girl,” Mateo replied, and the two men laughed.

“No foreigners in your party?”

“I believe you just asked me that, yes?” He couldn’t decide if the detective was merely fishing. “Why do you ask, my friend?”

Mateo had to be careful. The detective knew more than he was letting on; perhaps someone had mentioned seeing Mateo in the company of the yanquis, buying them drinks. He was a man known for mixing business and leisure, the two modes hardly separable for him. None of which was truly compromising, so long as he didn’t get caught in a lie.

“One witness reported seeing foreigners in the club,” the detective said. “I wondered if you met them, maybe spent time or some friendly cash on them.”

“What good would foreigners be to your case? They were not part of the fight, this much I can be sure of. What are the chances they witnessed anything in so large a crowd of people?”

“Well, Americans often make the best witnesses,” the detective said. “They are cooperative, they wish to see justice move swiftly so they can get on with their lives. Our judges find them reliable. We have a society that puts its trust in Europeans of all stripes, no sense pretending otherwise.”

The detective himself was a mulatto with a long jaw, a thin smile, an even thinner mustache, and cobalt eyes. When he spoke he showed no teeth, curling his lip so that one of his nostrils flared even as the thin mustache tented, then fell. It was hard to determine whether there was any bitterness in what he said. Mateo had known all along why the police and lawyers might be interested in tracking down Scott and Zelda. It was true, Americans were good for clearing cases. Even if Zelda had seen nothing, the police might persuade her to identify a suspect who resembled the blurred image of her memory, and whatever she said, the prosecutors could make it stick.

“In your opinion, the victim will recover, yes?”

“Of course this makes all the difference.” The detective smiled wryly. “If he recovers, it’s a petty squabble over some girl that got out of hand, American, Cuban, it does not matter. Two gamecocks preening for a female. We have all been subject to such fits on occasion.”

“Yes,” Mateo said, “a spontaneous crime, the passion of jealousy, hard to say which of the two was to blame.”

“Except one has not regained consciousness,” the detective said.

“And, of course, the assailant stabbed the man after he stumbled,” Mateo replied. “He must be held accountable. Intentions do not always matter under the law. I will keep my ear to the ground and maybe I will stumble across your Americans.”

“You’ll let me know if you hear from them, is that what you’re saying, sir?”

“Duties of a citizen,” Mateo replied, and rose to take his leave.

He walked out of the office convinced that the detective was holding out on him. It would take some maneuvering, but he could track down the necessary information—was the wounded man dead or alive, and if hospitalized, what were his chances?—before the day was done. He might as well start at the top: General Benitez, chief of police. Mateo had made Benitez money several times over on a string of investments. Benitez would tell him what he needed to know.

In the afternoon Mateo kept a reporter at the Havana Post from running a story about the Fitzgeralds’ visit to the Old City in the society pages. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say he bought himself and the Fitzgeralds some time by promising to get together with the reporter the next afternoon. Mateo’s motives in protecting the American couple weren’t entirely mercenary. Something about Scott reminded him of his younger brother. Of course, Mateo’s break with his family in Santiago had strained his relationship with his brother, whose politics were as twisted and reactionary as those of the rest of the family, but nevertheless every now and then Hector traveled to Havana and they met for dinner, drinks, and conversation about their favorite baseball players over Por Larranaga cigars. During his youth, Hector had been a hard drinker always in trouble with their father, and the only one who stuck up for him was Mateo. Scott too had the habits of the hard drinker and the kindly soul often at odds with authority, and from his days in New York City, Mateo remembered such men of talent fondly, tolerant of their bohemian, sometimes squalid tendencies. Everything had been so aimless in the Village in the twenties, the parties so free and licentious; some men never righted themselves afterward.

But what was Scott’s story? There was an air of irrepressible poise about him, the style of someone who’d made a success in the world but now exuded whiffs of intermittent hard luck. If he was writing for Hollywood, he must be doing pretty well.

***

They visited an old church on the hacienda, the doors still open for Sabbath devotions, several local women lingering to light candles and recite rosaries in the pews nearest the altar. Zelda redeemed herself in the eyes of their guide when she too insisted on lighting a candle.

“Your wife is religious,” he said to Scott as he observed her crouching low in one of the pews, genuflecting as she dropped to her knees. Scott, while apparently studying the altar, wondered what Mateo had intended in procuring this guide for them. Was it a way of keeping track of them? And if so, for what purpose? “My wife, Dios la bendiga,” the guide continued, “was also a holy woman all her life. Now she is dead, sometimes I tell my friends, who is to look out for my soul? All the women of Cuba, they are religious. This is a country in which God matters, the women look after us.”

Mentored throughout his teen years by an avuncular priest whom he had loved as a father, Scott had lost his feeling for God in his early twenties, but he couldn’t enter a church without awakening the rhythm of belief, if only in the echoes of his love for that kindly, cultured man. On dipping fingers in a font of holy water, crossing himself and murmuring a prayer without consciously thinking about the words, he felt a calm flow through him. It was like returning to a place where he belonged, his wanderings completed, as though life were a journey on the order of the prodigal son’s, your greatest ambition to get back to where you started.

So Zelda prayed while he and the guide toured the church, Famosa Garcia deciphering some of the finer details of the stations of the cross, revealing demons crouched in the corner of a stained glass window that displayed Jesus scourged. He said mysteriously, “Are sacred places not worth fighting to preserve? You would agree, yes, churches cannot be desecrated, men and women of God should not be forsaken?”; and Scott understood him to be speaking in code of Spain and the victorious alliance of royalists, clergy, and nationalists. The afternoon sun slanted through the windows above the chancel, suffusing the marble in an arrow of colored light that folded over the altar rail, casting shadows into the nearby pews. Those at the back of the church where Zelda knelt were darker still. It was time to leave, so he slid into the pew beside his wife, her eyes shut tight, lips fixed in beatific contentment. He tapped her on the shoulder several times. She smiled as she lifted her head to see him sitting next to her, as if she were used to him at last. They exited the church in silence.

“I wasn’t unbearably rude earlier, I don’t think,” she said to Scott as she drank wine over a late lunch. She probably shouldn’t be drinking wine—how many times had the doctors taken him aside to remind him that alcohol wasn’t good for her and he must avoid drinking in her company? But he was exhausted from the sightseeing, eyes heavy from lack of sleep, simply too weary to police her choices.

“Scott, didn’t you sleep well? You have bags,” she said, running her finger into the bone-sore sockets above his cheekbones. He wondered if she had no memory of asking him last night to watch over her while she slept or of his combing her temples with his fingers as she purred gratitude. Not until she was all the way under, more than an hour later, was it safe to leave her, and still he lay at her side, waiting until sunlight was leaking beneath the curtains to slip next door to his own bed.

“You didn’t answer my question, whether you thought I was terrible to the guide earlier.”

“I thought it was a statement.”

“You think he’s forgiven me, then?”

The table at which they sat, in a cafe in a small fishing village along the northern coast, faced the Gulf of Mexico. From its stilted wood deck they looked out over a harbor where small to midsized ramshackle fishing boats, some no bigger than dinghies, docked along two weather-beaten piers that jutted out into the expanse of ocean beyond. The boggy seawater, full of reeds and cattails closer to shore, ran up to and beneath the deck of the cafe. Not much of a breeze today, but the coastal air was cool, pleasing in its briny stench. Flies settled on the pink meat of the guava slices set before them. The waiter returned with bowls of mussels, fish, and lobster in a red broth. Scott ordered another rum and a bottle of Pepsi-Cola. The waiter, when he wasn’t tending to Zelda and Scott, talked with their guide at the bar, the restaurant otherwise empty at the siesta hour. “We keep eating when we should be sleeping,” Zelda remarked midway through her bowl of soup. All he had a taste for was the guava, though the thickening flies (he waved them off every now and then) discouraged his enthusiasm for the tart, pasty fruit. Several times Zelda looked up from her bowl to suggest Scott try the soup, and for God’s sake stop waving at the flies, there was nothing to be done about them, but he continued to sip his cola, occasionally flapping his hand, his chair pulled out from under the table’s umbrella into sunlight because it was too cool in the shadows.

“I feel rather bad for the poor man now,” Zelda was saying. “He held up bravely under my derision, in his own servile way.”

“He’s making a living, Zelda. Just getting by, like the rest of us.”

A copy of yesterday’s Havana Post, an English-language daily, lay on the table next to them and she retrieved it, flipping absentmindedly through its pages.

“But he’s forgiven me,” she said, trying to find a headline that grabbed her. “I can tell. What did he say again about his wife?”

On the fifth page, as if she had been searching for it, she discovered under the headline “Wings Over Cuba” their names in print: “Arrivals from Miami by plane yesterday were F. Scott Fitzgerald, novelist writer from Hollywood, Calif., and Mrs. Fitzgerald.” She was his spouse, nothing more, but to the world at large they were still a couple of note, the writer and his wife.

“When you were praying in the church,” Scott was saying, “Senor Famosa Garcia told me that you reminded him of his wife.”

“And she’s dead?”

“For several years.”

“Then he’s definitely forgiven me,” Zelda said, folding shut the newspaper. “We’ll make it up to him by asking if we can take a picture with him. Does he know who you are?”

“I’m sure it would mean nothing to him.”

From the beach below came a rush of angry voices in Spanish, and as Zelda darted to the rail of the deck, Scott rose slowly, tired of alarm. Two young boys had been fishing with hand lines from the shore, and one of them had hooked a sizable fish, fighting it by backing up the beach in order to wear it out. In his distracted state, he had walked his own line straight into that of the other boy. At the rail Scott heard the explosion of the fish breaking the surface maybe twenty yards from shore, magnificently iridescent in the sun as it slapped sideways on the water and disappeared again. The boy who had hooked the fish became all the more frantic. He let out line from his stick as the fish ran, let the stick on which the line was wrapped rotate like a motor in his palms so as to avoid slicing his fingers, and when the fish no longer ate up line, he again backpedaled up and away from the shoreline, tugging at the hopelessly tangled lines and shouting in Spanish at the other boy who followed him only because he had to. The owner of the cafe descended a wood staircase to the beach, striding across the blanched sand to settle the dispute. As soon as he reached the two boys, each plunged into his version of events, gesticulating fiercely, now and then pointing to where the fish had jumped. When it again broke the surface, the owner of the cafe pulled out a knife, biting its leather handle to hold it between his teeth as he assumed possession of the two sticks on which the lines were wrapped.

“He’ll have to cut the lines,” announced Famosa Garcia as he came forward to perch his forearms on the rail. “It’s only the one with the fish on it that matters, of course.”

“He seems to be gathering a lot of line,” Zelda remarked as the cafe owner cautiously wrapped the lines together around the conjoined sticks.

“That’s no way to catch a fish as strong as the one the boy has hooked. My friend is letting the eager one down easy, would you say; he is doing everything to pretend they will catch the fish. Cuando el pez huye de nuevo, when it makes its run, the boys will comprehend necessity. The fish is too far out. Without a proper reel, it will take all day, hours and hours, to pull it in.”

“And the sharks will claim it before then,” Scott said.

“This could be true,” the guide replied.

He seized this opportunity to hand Scott an envelope on which were written the words “To Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald,” and for a second Scott imagined the note might be from Ernest, who’d learned somehow (Max might have told him, after all) that Scott was in the country. Scott tore it open, but when he didn’t recognize the handwriting, he glanced down at the signature. In the note Mateo Cardona inquired after Zelda and expressed his hopes that the Fitzgeralds were enjoying the expertise of one of Havana’s finest guides. He closed with an invitation to join him for drinks and dinner at La Floridita tomorrow, the restaurant for which Scott, Mateo, and the girl had started only last night. “Arrive by eight,” Mateo instructed. “I will meet you there and report on what I will have learned for you.”

“What does it say?” Zelda asked, sidling up next to Scott and the guide, resting her forearms on the rail, which suddenly bowed forward, not just a few inches as if testing the groove in the newel but rather a full foot or more, bending like the string of an archer’s bow, even as Zelda’s trained instincts as a ballerina took over. It was as though she’d thrown herself too far forward during a performance, catching herself before anyone could detect the wobble, already recovering by the time Scott caught her dress at the waistband and wrapped his hand around her waist and brought her to him until they were posed in a travesty of the ballet’s “poisson position,” or “fish dive,” the woman with head tucked, dipping beneath the horizontal plane of the man’s hold. The guide hadn’t been so lucky. With no one to catch him, he pushed at the rail in an effort to right himself, but when the beam failed, popping free of the newel on one end and crashing to the deck, he could only fall to his knees, throw his legs into a baseball slide, and let his shins eat splinters as Zelda burst into laughter.

“Why are you laughing?” Scott asked. “You might have been seriously hurt.”

The guide, from his knees, was spewing a torrent of Spanish profanity.

“I tell my amigo how many times, it is necessary to fix the rail,” he said, rising to his feet, gaping at the strangely laughing woman.

“You two are awful bores,” she said. To the guide she added, “If only you could have seen your face as you lost balance.”

“You wouldn’t be laughing if you’d plunged into the water,” Scott said.

“Maybe, maybe not,” she said. “But comedy is all about what hasn’t happened to you. And it’s funnier when it could have been you, but it’s somebody else instead.”

They could hear the cafe owner’s sandals on the staircase. He had sprinted across the beach as soon as he heard the crashing beam, relieved now to find that everyone was all right, unwilling to surmise how many times he’d asked the village carpenter to look at that post. Zelda wandered to a darkened corner of the cafe. “Does this work?” she called to the owner, drawing everyone’s attention to a camera on a shelf loaded with plates and pitchers, its stand propped against the wall beneath the shelf.

It did in fact work, though the owner wasn’t sure there was any film in it just now.

“Then you must find some film,” Zelda said. “We’ll pay, of course. We want a picture with your friend, our guide for the day, who has been so lovely and patient with us.”

The guide might have been angered by Zelda’s fit of laughter, but her talent for finessing people prevailed. Once he realized she was asking to have her picture taken with him, he took on the role of intercessor, negotiating with the owner as to where they might find film and how much it would cost, the owner now hastening away in search of the film. In his absence, the boys from the beach climbed halfway up the stairs, complaining that the cafe owner had cut their lines and allowed their fish to get away. It was clear they felt that something was owed them for their loss, and they appealed to Scott, asking him if he spoke Spanish, until Famosa Garcia came to the top of the staircase, recommending that they renew their labors. “Debe pescar otro pez,” he shouted, waving them away. Another fish, that was the answer. “Eso es todo lo que se puedes hacer ahora.”

The cafe owner returned with a pad of film, and Zelda told him exactly where to set up the camera. Minutes later she was traipsing across the sandy lot toward the black Plymouth sedan, the photograph wedged between the pages of a book, the negative in her hand.

The unhappy boys loitered near the car, again drawing near to Scott to see if he would compensate them for their loss, again chased off by Senor Famosa Garcia, less kindly the second time around.

“They are unfortunate today,” the guide said with a sigh, “and wish to blame somebody.”

“You are a handsome man,” Zelda told the guide, entranced by the photograph, talking to his image rather than the man himself. “And you liked having your picture taken with us.”

In the backseat she was distracted, her mirth quieted by the shock of studying herself, the crooked smile, her face gaunter than she remembered it. She recognized the roundness in her cheeks, flushed and healthy from the day’s activities, but she couldn’t quite place the eyes, so small, stealthy, and averted. She was never sure how she would photograph, her responses to her image ranging from alienation to full-on disgust to the despairing conviction “That’s not me.” Even in the prime of youth, when the camera had liked her as much as anyone she knew, friends used to remark that she never took the same picture twice.

It was true, you could run through photo albums, through the pictures in magazines, and there was Zelda in shots taken within minutes of one another, often by the very same photographer, yet she appeared as two entirely different women. More peculiar than how it portrayed her eyes, though, were two facts about the picture in her hand: first, it showed Scott and her together, after all these years still resembling a couple; and, second, it depicted the guide’s face as oddly familiar, the graying black mustache and strong chin underneath a straw hat wrapped in a black band.

It took her a minute, but then she understood. “You remind me of an old friend of ours,” she said to the guide as they rode into town, waving the photograph in front of Scott’s nose, asking if he too could discern the resemblance.

Next: Chapter 6.

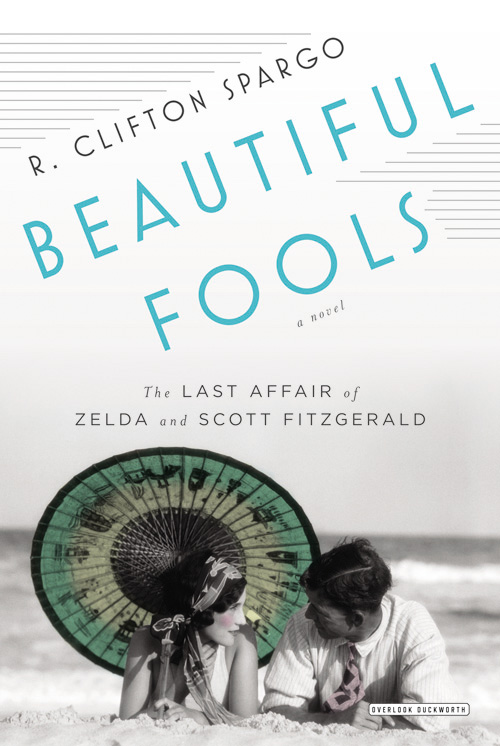

Published as Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald by R. Clifton Spargo (NY. Overlook Duckworth, 2013).