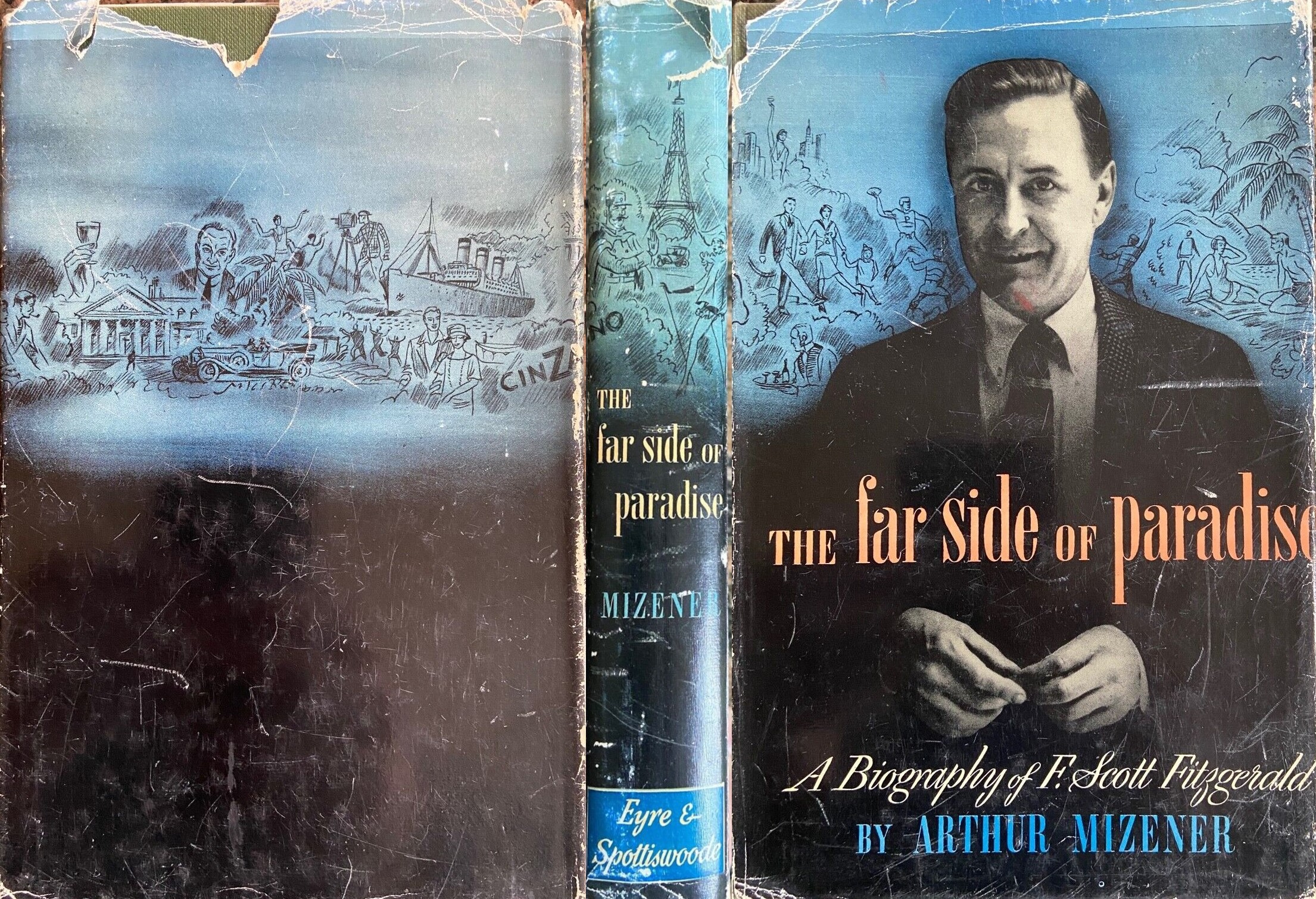

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter XV

Ever since he had got into financial straits, Fitzgerald had thought of trying to get to Hollywood again. During 1936 he had worked to find a job there. What was to be his last story for the Post was written in June (“Trouble”; it was not printed until March, 1937), and, apart from an occasional story for Collier’s or Liberty, he was now pretty much committed to Esquire. The effect of this change of market was to cut the price of his work to a tenth of what it had been. His income reached a new low in 1936 ($10,180) and would have fallen to half of that in 1937 had he not gone to Hollywood. All this he could foresee.

But his attempts to get a foothold in Hollywood were “compromised” as he put it by the “Crack-Up” articles. “It seems to have implied to some people that I was a complete moral and artistic bankrupt,” he wrote a friend. His indignant conviction that his alcoholism was only a malicious delusion of Hemingway’s made him blind to the wide public knowledge of his habits. Having his own rationalization of his case, he hardly understood how much “The Crack-Up” revealed and believed he was playing his cards cunningly when he was showing his hand most openly, as when he remarked in an aside that he had “not tasted so much as a glass of beer for six months.”

His attitude—it was intensified because the writer was Hemingway—showed in his response to the reference to him in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” In the original version of the story Hemingway’s hero thinks, “He remembered poor old Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of [the rich] and how he had started a story once that began, ‘The very rich are different from you and me.’ And how someone had said to Scott, Yes they have more money. But that was not humorous to Scott.” Neither was this.

The most famous of all anecdotes about Fitzgerald derives from this passage—and perhaps from Hemingway’s repetition of it in conversation. The story does not, as do most versions of the anecdote, claim Hemingway made this retort to Fitzgerald, though the implication is that he did. Perkins, however, wrote Fitzgerald that “I was present when that reference was made to the rich, and the retort given, and you were miles away.” This public reference to him astonished and enraged Fitzgerald, and he wrote Hemingway, “Please lay off me in print. If I choose to write de profundis sometimes it doesn’t mean I want friends praying aloud over my corpse. No doubt you meant it kindly but it cost me a night’s sleep. And when you incorporate it (the story) in a book would you mind cutting my name?” “I wrote Ernest about that story of his,” he told Perkins, “asking him in the most measured terms [“a somewhat indignant letter,” he called it elsewhere] not to use my name in future pieces of fiction. He wrote me back a crazy letter, telling me about what a Great Writer he was and how much he loved his children, but yielding the point—’If I should outlive him—’ which he doubted. To have answered it would have been like fooling with a lit firecracker. Somehow I love that man, no matter what he says or does, but just one more crack and I think I would have to throw my weight with the gang…” Fitzgerald's admiration for Hemingway endured to the end. Six months before he died he asked Perkins: 'How does Ernest feel about things? ... I would be interested in at least a clue to Ernest's attitude.' Two months later he was again asking: 'What about Ernest? What does he think?'. Hemingway’s letter—unfortunately lost—was not so irrelevant as Fitzgerald suggests, for he also told Fitzgerald that “since I had chosen to expose my private life so ’shamelessly’ in Esquire, he felt that it was sort of an open season for me….” And though Fitzgerald ironically attributes his restraint in not replying to “approaching maturity on my part,” it was his myth about Hemingway which saved him from sending the “hell of a letter” he wrote. “[Ernest] is quite as nervously broken down as I am,” he said, “but it manifests itself in different ways. His inclination is toward megalomania and mine toward melancholy.” Hemingway quietly dropped Fitzgerald’s name (it became “Julian”) when “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” appeared in The First Forty-Nine Stories.

Just as he was astonished to discover that Hemingway would venture this reference and that “‘the poor old Scott’ line… has been a standby of my dear friends for almost a decade,” so he was surprised when Hollywood drew back after “The Crack-Up.” But he kept trying for a job and in August he got an offer to go out and do a story “of adolescents around seventeen.” The contract was to be for four weeks at $1500. Because of his shoulder he had to refuse, but by the following April he had another feeler. In June the arrangement was completed. He was to go to M-G-M for six months at $1000 a week with an option for twelve months more at $1250. This option was in due course picked up.

Since one of his main motives for going to Hollywood—though not the only one—was to pay his debts, the first thing he did was to make an arrangement with his agent, Harold Ober, to do so. His plan was to deposit his salary with Ober, who would then give him $400 a month, to support himself, keep Scottie in school and Zelda in Highlands. The rest was to be set aside for taxes and payments against his debts to Ober and Perkins and, later, Scribner’s. These debts amounted, according to his own estimate, to something like $40,000 at the time. In March, 1940, Zelda left Highlands on the understanding that she would live quietly with her mother in Montgomery. For several years she spent most of her time there and this arrangement reduced Fitzgerald's expenses appreciably. The record of Fitzgerald's debts is incomplete, but $40,000 is certainly not an over-estimation of them. He maintained substantially this arrangement until his debts were paid.

But though the clearing of these “terrible debts” was veryimportant to him, he also felt something of the old fascination of Hollywood and the old desire to conquer it. It was a place that he had never got the best of. To those who might think Hollywood a surrender he let his doubts have the upper hand. “It’s a hell of a prospect in every other way except money,” he wrote his cousin Ceci, “but for the present & for over 3 years the creative side of me has been dead as hell.” But at exactly the same time (both letters were written on the train on the way out) he was writing Scottie:

I feel a certain excitement. The third Hollywood venture. Two failures behind me though one no fault of mine….

I want to profit by these two experiences—I must be very tactful but keep my hand on the wheel from the start—find out the key man among the bosses and the most malleable among the collaborators—then fight the rest tooth & nail until, in fact or in effect, I’m alone on the picture. That’s the only way I can do my best work. Given a break I can make them double this contract in less than two years.

It was this feeling of excitement that stayed with him, so that when he was making jottings for The Last Tycoon he reminded himself of “my own fears when I landed in Los Angeles with the feeling of new worlds to conquer in 1937….” And it was with this ambition to conquer that he tackled his job. He spent much of his spare time having pictures run off for him and studying other writers’ scripts, and he kept a file of notes on the pictures he had seen. As late as November, when he had finished a revision of A Yank at Oxford and was hard at work on Three Comrades, he called himself “a semi-amateur” at movie construction (“though I won’t be that much longer”). He was determined, this time, to do a good job, to give everything he had. For a while he kept completely sober, and as long as he was under contract to M-G-M he only went on an occasional bust. '... there were only three days while I was on salary in pictures that I ever touched a drop. One of those was in New York and two were on Sunday.' This is an exaggeration on the side of virtue, but it is substantially true that drinking did not affect his efficiency for some time in Hollywood.

In July he got Helen Hayes to bring Scottie out to spendthe rest of the summer with him and when she had returned to Miss Walker’s he wrote her one of his oddly touching letters. “I think of you a lot,” he concluded. “I was very proud of you all Summer and I do think that we had a good time together. Your life seems gaited with much more moderation and I’m not sorry that you had rather a taste of misfortune during my long sickness, but now we can do more things together—when we can’t find anybody better. There—that will take you down! I do adore you and will see you Christmas. Your loving Daddy.”

All through the autumn he continued to write enthusiastically about what he called this “tense crossword puzzle game, creative only when you want it to be, a surprisingly interesting intellectual game.” His good health and morale, “miraculously returned after three terrible years,” were a continual surprise to him. In the first week of September he came east and took Zelda on a trip to Charleston which went off without a hitch. Again at Christmas time, in spite of his being dead tired from a final rush of work on Three Comrades, he took Zelda to Miami and Montgomery and back to Asheville without incident. He entered into the social life of Hollywood with a renewal of his old innocent delight in big names. “Had the questionable honor [of] meeting Walter Winchell, a shifty-eyed fellow surrounded by huge bodyguards,” he wrote Scottie. “Norma Shearer invited me to dinner three times but I couldn’t go, unfortunately as I like her. May be she will ask me again… Took Beatrice Lily, Charley MacArthur … to the Tennis Club the other night, and Errol Flynn joined us—he seemed very nice though rather silly and fatuous.”

But in spite of his improved health and his genuine enthusiasm for his job he was neither a well man nor one with much in reserve. Moreover, it showed. “There seemed to be no colors in him. The proud, somewhat too handsome profile of his early dust-jackets was crumpled…. The fine forehead, the leading man’s nose, the matinee-idol set of the gentle, quick-to-smile eyes, the good Scotch-Irish cheekbones, the delicate, almost feminine mouth, the tasteful, Eastern (in fact, Brooks Bros.) attire—he had lost none of these. But there seemed to be something physically or psychologically broken in him that had pitched him forward from scintillating youth to shaken old age.” He soon dropped out of the social life of Hollywood; it was too much for him, and he no longer liked parties anyhow. Insomnia continued to bother him, and he went on feeling uncertain about his own purpose and identity, feeling that he was watching “the disintegration of [his] own personality.”

All his life he had depended on his belief that he could hold the part of himself that responded to experience without restraint and the morally responsible part of himself, the spoiled priest, in reasonable balance. This was a matter of the spoiled priest’s understanding the responsive self, knowing the reasons for his outbursts, and, when necessary, bringing him to heel. He was thinking of his own failure to maintain this balance when he wrote his daughter, “Baby, you’re going on blind faith… when you assume that a small gift for people will get you through the world. It all begins with keeping faith with something that grows and changes as you go on. You have got to make all the right changes at the main corners—the price for losing your way once is years of unhappiness.” He put the point even more strongly to a girl who began to go to pieces when he broke off a love affair with her in 1935: “The luxuriance of your emotions under the strict discipline which you habitually impose on them makes that tensity in you that is the secret of all charm—when you let that balance become disturbed, don’t you become just another victim of self-indulgence—breaking down the solid things around you and, moreover, making yourself terribly vulnerable?”

When he began, in 1928 and 1929, to suspect that the spoiled priest had lost control, he was seriously worried; by 1932 he was saying even to Perkins, with whom he always tried to maintain the pretense that he was in better control of himself than he was, “Five years have rolled away from me and I can’t decide exactly who I am, if anyone…” After the terrible year of 1936, the spoiled priest no longer knew what his experiencing self had become, and he felt his personality had disintegrated. It was no longer a matter of keeping faith with something that had grown and changed; now he could not even find that something. Once during his early days in Hollywood he sent himself a postal card which he carefully preserved. “Dear Scott,” it said, “—How are you? Have been meaning to come in and see you. I have [been] living at the Garden of Allah. Yours Scott Fitzgerald.” Once during this time, in a moment of drunken despair, he tried to commit suicide, but that was not characteristic; he had far too much sense of responsibility for Scottie and Zelda, and too much courage too, not to go on doing the best he could however little meaning it had for him.

He was, a good deal of the time, great fun to be with, he listened as well as he talked, he could be terribly funny, terribly serious, and sometimes, happily, both at once. Possibly half a dozen times I had seen him difficult and belligerent, and then he could be maddening, but it would be badly misleading to picture him as staggering through those last Hollywood years… my most lasting impressions are not of his drinking and falling, but of his thinking and trying.

But in an important sense Scott Fitzgerald was never, as a personality, wholly there again; to old friends like Edmund Wilson he seemed like a polite stranger when he and Sheilah stayed with the Wilsons in the fall of 1938. For brief moments sometimes, like Dick Diver, “he relaxed and pretended that the world was all put together again,” but most of the time for the rest of his life he was a man mostly going through the motions, scarcely believing in the reality of anything hefelt or did except when, drunk, his despair exploded into terrifying violence. Several such occasions are unforgettably described in Beloved Infidel.

Once, for example, when he was drunkenly annoyed with Sheilah for throwing out two bums he had been entertaining at Encino, he threw a bowl of soup across the dining room and, when the nurse tried to calm him down, kicked her viciously and then began trying to hurt Sheilah by reminding her of her most painful secret, her origins in the East End of London as Lily Sheil; finally he started looking for his gun, saying he was going to shoot her. Fortunately she and his secretary had hidden the gun and she escaped, but for days he went on threatening her. When he finally sobered up, he wrote her: “I loved you with everything I had, but something was terribly wrong. You don’t have to look far for the reason—I was it. Not fit for any human relation. … I want to die, Sheilah, and in my own way.” All of him that remained intact—indeed, it grew stronger—“was his gift, though the exercise of it was inhibited by his lack of physical energy. Nevertheless, when he was fully roused by a subject, as he would be once more by the subject of The Last Tycoon, he could write better than ever.

In October he got a wire from Ginevra King, who was visiting in Santa Barbara. It filled him with such excitement about the past that he considered what course to follow like a problem in high diplomacy. “She was the first girl I ever loved and I have faithfully avoided seeing her up to this moment to keep that illusion perfect, because she ended up by throwing me over with the most supreme boredom and indifference. I don’t know whether I should go or not. It would be very, very strange. These great beauties are often something else at thirty-eight, but Genevra had a great deal beside beauty.” But he went and they had lunch together. “[We] had a much better time than I had anticipated,” Mrs. Pirie (Ginevra) remembered. “Afterwards … he suggested we go to the bar—I settled for a lemonade but he insisted on a series of double Tom Collins. I was heartsick as he had been behaving himself for some months before that. For the next few days I was besieged with calls, but as he was in love with someone in Hollywood, I believe, he soon gave up the pursuit.” “She is still a charming woman and I’m sorry I didn’t see more of her,” Fitzgerald wrote.

He was in love with Sheilah Graham, then just beginning her career as a columnist in Hollywood. Born Lily Sheil in London’s East End and brought up in an orphanage, she had indomitably made her way in the world, first by a strange but successful marriage with a much older man, then as a chorus girl, and finally as a journalist. From the beginning she showed a determination to dominate the world that must have been part of her appeal to Fitzgerald. The very first time she came into the office of James Drawbell (then editor of the Chronicle), “a chorus girl with a strange idea in her head,” she had her career all mapped out. “I “want to get on to a newspaper, then I want to go to New York and work there, and after that—Hollywood,” she told him, and, astonishingly enough, that is exactly what she did.

Before she left London she even managed to move familiarly in what were quite elevated social circles. It does not seem likely that the Duchess of Devonshire and her friends were quite so deceived by Sheilah’s imaginary account of her respectable social background as she believed they were; it must have been their appreciation of the naïveté of her belief in the value of such a background and the heroic energy with which she played her role that gave this very pretty girl her charm for them. So at least I have been told by people who knew her at this period in London. She herself reports that at St. Moritz one of these people she thought she was deceiving quietly called her an adventuress. For all her drive and ambition, she was essentially young and innocent and touching—even more appealing because, not recognizing the real source of her charm, she had no vanity about it.

She and Fitzgerald first saw one another—just over a week after Fitzgerald had arrived in Hollywood—at a party ofRobert Benchley’s, oddly enough a party to celebrate her engagement to a British gossip columnist, the Marquis of Donegall. Fitzgerald thought she was the European actress Tala Birrell. At a Writers’ Guild dinner sometime later they were at nearby tables and spoke fleetingly, but another week passed before Fitzgerald made sure who she was and persuaded Jonah Ruddy to take them out to dinner together; that night Fitzgerald had all his old wonderful charm, and before it was over Sheilah was well on her way to loving him (Except where I have indicated otherwise, my account of the relations between Fitzgerald and Miss Graham depends on the vivid account Miss Graham herself has given in Beloved Infidel, pp. I72-338.)

The best account there will ever be of how Fitzgerald felt about Sheilah is the story of Stahr and Kathleen in The Last Tycoon. Almost every detail of their falling in love is there, i reimagined to fit the circumstances of Stahr’s story but unchanged in feeling. Fitzgerald’s confusion over Sheilah’s identity and his overwhelming sense of her resemblance to Zelda is in Stahr’s mixing up Kathleen and her friend Edna and his haunted sense of her resemblance to his dead wife, Minna; his brief glimpse of Sheilah at the Writer’s Guild dinner is in Stahr’s glimpse of Kathleen at the screen-writers’ ball at the Ambassador; his response to Sheilah’s engagement to a lord and to her joking assertion that she had had eight lovers is in Kathleen’s casual revelation that she had been a king’s mistress; the drive to Malibu, when Sheilah told him the true story of her life, is in the drive to Stahr’s unfinished house where he and Kathleen consummate their love. Above all Fitzgerald’s devotion to Zelda and the past is in Stahr, who is “in love with Minna and death—with the world in which she looked so alone [when she was dying] that he wanted to go with her.”

Zelda was supposed to know nothing about Sheilah, but some suspicion—perhaps aroused by her knowledge of how close Fitzgerald's books always were to his experience—must have led her to say of Kathleen: 'I confess that I didn't like the heroine [of The Last Tycoon], she seeming the sort of person who knows too well how to capitalize the unwelcome advances of the ice-man and who smells a little of the rubber-shields in her dress.' Fitzgerald's notes for The Last Tycoon show that even the silver belt with stars cut out of it that Stahr remembers from his first meeting with Kathleen was Sheilah's, though she does not mention it in Beloved Infidel.

Fitzgerald’s portrait of Kathleen shows us a girl of great beauty with a past so strange that she can be wholly ignorant of the most commonplace facts of the world she is now living in—as Sheilah, living among the writers and intellectuals of Hollywood, had never heard of Willa Cather—and at thesame time take for granted many hard facts of life that she had been facing undaunted for years, facts that few of these intellectuals had ever known at first hand. It makes her at once naive and unshockable. The only thing Sheilah was really frightened of was that some one might discover the truth about her past. When she broke down under Fitzgerald’s characteristically relentless cross-examination and told him the truth about herself, she was convinced he would cease to care for her: “he’ll never want to see me again. I’m drab, drab, all the glamor is vanishing,” she thought.

Apart from the strength of her feeling for him that that confession shows—she had never told these things to anyone before—there is the pathos of her thinking the truth about her would make her seem drab, when it was much more likely to appeal strongly to Fitzgerald’s imagination and make them much closer than before. For much of his life Fitzgerald had seen himself as a man trying to play a role, a man who lived among the rich and successful without being one of them. The very fact that he now thought of himself as having failed in that role would only make Sheilah’s success in hers the more appealing to him. No one understood better than he the needs of the imagination that could drive one to such a deception or the cost and heroism of living it. From the moment Fitzgerald understood the whole truth about Sheilah, he fought—not always wisely but always with everything he knew—to help her carry off her role. Her energy and courage must have been a constant pleasure to him, and her success—despite its constant, painful emphasis of his own obscurity—a compensation.

In the fall of 1937 Sheilah broke her engagement with Lord Donegall, and almost immediately, on a trip to Chicago he took to help Sheilah with a radio broadcast, Fitzgerald began to drink, and for the first time since she had known him Sheilah saw the other Fitzgerald. As usual, he told everyone on the plane who he was; he made ill-timed belligerentgestures that were meant to help Sheilah with the radio people; he led on a girl in the airport bus with compliments (“Isn’t she pretty? Such lovely hair, such poise—a very lovely young woman”) and then suddenly said to her, “You silly bitch.” When Sheilah finally got him to the airport he was too drunk to be allowed on the plane and they had to wait over five hours for the next flight. To keep him out of bars, she drove him around in a cab for the whole time and finally got him sober enough to fly back to Hollywood (Even this refusal of the authorities to let him on the plane gets into The Last Tycoon, in the episode in the Nashville airport.). When Sheilah stuck to him through all the awful time, she really made her decision, and despite the two times later when she left him, she was committed to him from then on.

Fitzgerald did not commit himself so quickly; perhaps he never wholly committed himself. It was not that he did not love Sheilah as much as he was capable of loving anyone new, but he worried about his capacity to live this new life and also to carry his obligations from the past. As late as January, when he went East, he talked the whole matter over doubtingly with Nora Flynn. Her letter to him about their conversation shows how he felt. “I am sure you are doing the right thing—about Zelda—I know you have been beyond words, wonderfull to her—I also know that the time has come for you to have a life of your own—to choose your own life, not for Zelda or for Scottie but just for you… I have a strange feeling that Sheilah is the right person for you…” So, within the limits of his nearly exhausted and already heavily committed emotional capital, Fitzgerald gave himself to this relation.

It was the luckiest thing that could have happened to him. It gave him someone he cared for very much to live with and to worry over and fight for, something he had not had since he and Zelda had begun to quarrel bitterly in the late twenties. His bouts of drinking were not something that could be stopped by anyone’s care and good sense, however much he might love her, as Sheilah soon discovered, as perhaps Zeldain her different way had discovered before her. Fitzgerald had a pride that would not allow him to accept such help, and perhaps it could not have been enough even if he had accepted it, for deep down in him there seems to have lingered his old belief that the only way he could keep his feelings alive for his work over long stretches was by drinking, and for all anyone can tell he may have been right. Nevertheless, the peace and order and happiness Sheilah brought into his life drastically reduced the times when he felt he had to drink, and he went long spells—the last one over a year—without doing so.

By the end of January, 1938, he had completed the script of Three Comrades and had the characteristic Hollywood experience of having the producer, Joseph Mankiewicz, spoil all that he thought best in it by rewriting it. In rage and anguish he wrote Mankiewicz:

Well, I read the last part and I feel like a good many writers must have felt in the past….

To say I’m disillusioned is putting it mildly. I had an entirely different conception of you. For nineteen years… I’ve written best selling entertainment, and my dialogue is supposedly right up at the top. But I learn from the script that you’ve suddenly decided that it isn’t good dialogue and you can take a few hours off and do much better….

Oh, Joe, can’t producers ever be wrong? I’m a good writer—honest. I thought you were going to play fair.

But there was nothing to be done except to make an ironic portrait of Mankiewicz for The Last Tycoon. This was the end of any real hope Fitzgerald had of getting creative satisfaction from his work in Hollywood. He was now thinking of it as “a strange conglomeration of a few excellent overtired men making the pictures, and as dismal a crowd of fakes and hacks at the bottom as you can imagine.” But he went back to playing the crossword puzzle game on a new picture for Joan Crawford called Infidelity. He was not excited about it as he had been about Three Comrades, only tired and a little sardonic. “Writing for [Joan Crawford] is difficult,” he wrote Gerald Murphy. “She can’t change her emotions in the middle of a scene without going through a sort of Jekyll and Hyde contortion of the face, so that when one wants to indicate that she is going from joy to sorrow, one must cut away and then back. Also, you can never give her such a stage direction as ‘telling a lie,’ because if you did, she would practically give a representation of Benedict Arnold selling West Point to the British.” In July he wrote Scottie quite seriously, “I don’t think I will be writing letters many more years and I wish you would read this letter twice…. You don’t realize that what I am doing here is the last tired effort of a man who once did something finer and better.”

In April they ran into censorship trouble over Infidelity and with most of a good and difficult script written, Fitzgerald had to drop it. It was never revived. For the duration of his contract with M-G-M he worked on The Women and Madame Curie. Because of his disappointment with movie work he began to think of writing again. “I don’t write any more,” he had said to Thornton Wilder. “Ernest has made all my writing unnecessary”; and in the fall of 1937 he had said without irony to Perkins, “All goes well—no writing at all except on pictures.” But by April he was saying that “if I am to be out here two years longer, as seems probable, it certainly isn’t advisable to let my name sink… out of sight…” and making anxious proposals for various reprints. This anxiety continued to mount as time went by until, by 1940, he was saying to Perkins: “I wish I was in print… Would the 25 cent press keep Gatsby in the public eye—or is the book unpopular? Has it had its chance?… But to die, so completely and unjustly after having given so much. Even now there is little published in American fiction that doesn’t slightly bare my stamp—in a small way I was an original.”

That April Sheilah found a house for them at Malibu and Fitzgerald moved out there from the Garden of Allah, where he had been living since his arrival in Hollywood. His anxiety over Scottie now became even more intense than usual, for she was about to go to college. At the last moment, after a harrowing though innocent episode during College Board examinations the previous spring, she had been accepted by Vassar. Fitzgerald’s lifelong habit of identifying himself with those he loved—and he loved Scottie very much—combined with a flood of recollections of his own undergraduate days to make him even more than usually advisory. “[Vassar’s] position,” he wrote her delightedly, “is rather like Harvard’s—you’d have to include it in any list of the big three, while you could name Harvard, Columbia, and Chicago, and leave out poor little Princeton altogether.” He then redoubled his anxious, loving, exasperating efforts to help her manage her life wisely. “Poor Scott,” one of his friends said. “He had to go through Princeton and Vassar too!” He tried to choose Scottie’s courses and her friends for her; he spent hours making her outside reading lists and lists of questions about what he had told her to read; he harried and chivied her about the smallest detail of her life. When she went on too many weekends, or got poor marks, or ran into debt, he would write her violently angry letters. “I’m habituated to the string of little lies,” he would write, “… but this sort of thing can lead into a hellish mess…. Friends!—we don’t even speak the same language. I’ll give you the same answer my father would have given to me…. Either you can decide to make concessions to what I want in the East or you can come out here Thanksgiving and try something else…. With dearest love, believe it or not, Daddy.” Sometimes he would try irony, as when he scrawled at the bottom of a letter, “I have paid Peck & Peck & Peck & Peck & Peck.”

At one point Scottie’s adviser intervened in her defense. “To tell you the honest truth,” she wrote Fitzgerald, “I was horrified by your letter… because I can’t see how an eighteen-year-old girl could have behaved badly enough to merit so much parental misgiving and despair—such dark bodings for the future.” But Fitzgerald was quite unmoved; “I thought the letter from Miss Barber had a somewhat impertinent tone,” he said stiffly.

Most of the time, however, he was not angry, only inexhaustibly concerned. The letter he wrote her as she was starting for Poughkeepsie and her freshman year is typical:

Dearest Pie:

Here are a few ideas I didn’t discuss with you and I’m sending this to reach you on your first day.

For heaven’s sake don’t make yourself conspicuous by rushing around inquiring which are the Farmington Girls, which are the Dobbs Girls, etc. You’ll make an enemy of everyone who isn’t. … I’d hate to see you branded among them the first week as a snob. …

If I hear of you taking a drink before you’re twenty, I shall feel entitled to begin my last and greatest non-stop binge, and the world also will have an interest in the matter of your behavior. It would like to be able to say, and would say on the slightest provocation: “There she goes—just like her papa and mama.”…

I think it would be wise to put on somewhat of an act in reference to your attitude to the upper classmen. In every college the class just ahead of you is of great importance. … It would pay dividends many times to treat them with an outward respect which you might not feel….

Everything you are and do from fifteen to eighteen is what you are and will do through life. Two years are gone and half the indicators already point down—two years are left and you’ve got to pursue desperately the ones that point up!

I wish I were going to be with you the first day, and I hope the work has already started.

With dearest love—DADDY

Underneath everything there was his pathetic desire to participate in her life: “These are such valuable years. Let me watch over the development a little longer. What are the courses you are taking? Please list them. Please cater to me…. What do the Obers say about me? So sad?… What play are you in? … What proms and games? Let me at least renew my youth!… As a papa—not the made [mad] child of a mad genius—what do you do? and how?”

In October, because Malibu had become too cold and damp for Fitzgerald, Sheilah found a house on the estate of Edward Everett Horton at Encino in the San Fernando Valley; she gave up her own house, keeping only a small flat off Sunset Boulevard, and moved in with Fitzgerald. In November he took on what turned out to be a disastrous job for Walter Wanger. Budd Schulberg, then fresh out of Dartmouth and starting a career as a script writer, had been assigned by Wanger to a picture about the Dartmouth Winter Carnival. Wanger then decided there ought to be an older hand on the picture and hired Fitzgerald to collaborate with Schulberg. When he told Schulberg, he said, “My God, isn’t Scott Fitzgerald dead?” “On the contrary,” said Wanger, “he’s in the next office reading your script.”

It always raises doubts in a script writer’s mind when he has a collaborator assigned to him, but Schulberg knew Fitzgerald’s work and admired it and they got along fine during a series of long conferences that consisted mostly of discussions of literature. Schulberg remembers that he struggled unsuccessfully to bring together the world in which he had always imagined Scott Fitzgerald living and the world in which he himself wrote scripts. But though they seemed to make little progress with the script, Schulberg was not seriously worried; he supposed Fitzgerald, the experienced script writer, was quietly planning the picture and would presently say, “Here’s what we’re going to do.” Fitzgerald was worrying about the script, pacing his room nights over it, but he was not making much progress. This was the perilous stateof their work when Wanger decided that they must see the Winter Carnival itself and, despite Fitzgerald’s protest that he remembered undergraduate life very well, they found themselves boarding a plane for the East to join the crew already installed at Hanover waiting for the Winter Carnival and the script.

At the airport Schulberg’s father presented him with a magnum of champagne—it was his first big assignment—and after some hesitation Fitzgerald was persuaded to join Schulberg in drinking it. Sheilah was actually on the same plane, but she and Fitzgerald greeted each other as polite acquaintances and went their separate ways so that she was not aware of what was happening. In New York, Fitzgerald went on to gin and by the time they were on the train for White River Junction he was at the stage where he was telling everyone who he was and how much he earned. It is characteristic of the way he, like Gatsby, could, even when he was at his worst, get behind the conventional judgments and the self-interest of intelligent people that Schulberg, when he realized what was happening, put himself immediately and unequivocably on Fitzgerald’s side; he tried desperately to keep Wanger, who was also on the train, unaware of Fitzgerald’s condition. Then, despite his wretched condition—he had added a bad cold to his drunkenness and lack of sleep—suddenly at five in the morning Fitzgerald ad libbed a beautiful opening shot for the picture; it was like Gatsby’s proving to Tom Buchanan that he really was an Oxford man. With his usual impetuousness Fitzgerald insisted on waking Wanger up to tell him about his idea, thus alerting Wanger to his condition. But that was all the script they had when they arrived the next morning at Hanover to find the crew clamoring for something to shoot. Fortified by Wanger’s now dangerous impatience, Schulberg improvised enough to get them by for the moment.

Through some slip-up there was no reservation for the twowriters at the Inn and they were squeezed into an attic room with a double-decker bed. Fitzgerald insisted that this was a measure of Hollywood’s respect for writers. They spent that night in their attic room talking of Fitzgerald’s books; he was pathetically pleased to discover how well Schulberg knew them and began talking about himself with his characteristic, almost frightening detachment. “You know,” he said, “I used to have a beautiful talent once, Baby. It used to be wonderful feeling it was there….” Then for two days longer Fitzgerald wandered around Hanover with his cold and his four days’ growth of beard amidst the gloss and gaiety of the Winter Carnival, a tactless ghost from another age of college pleasures.

On what turned out to be their last evening he had just settled himself, very disheveled, at the Alpha Delt party when Wanger came in and ordered Schulberg to get him out of sight. Fitzgerald was full of the spirit of the occasion, however, and insisted on Schulberg’s taking him to the Psi U house. As they passed the Inn Schulberg tried to steer him to bed, but Fitzgerald heard in his voice the tone of a man handling a drunken friend and turned on him sharply. “You son of a bitch!” he said. “All right, I’ll go there by myself.” Schulberg finally got him into the coffee shop of the Inn, and there they dictated to one another a parody script. “We fade in on the thin clear cold slope of the ski slide,” they would say, “and fade through to the thin clear cold mind of a Dartmouth undergraduate.” After an hour or so they struggled out into the night again, and came face to face with Wanger. He took a good look at them and said: “You two are getting out of here, right away.”

“Wanger will never forgive me for this,” Fitzgerald said on the way to the Junction. “He sees himself as the intellectual producer and he was going to impress Dartmouth by showing them he used real writers, not vulgar hacks, and here I, his real writer, have disgraced him before the whole college.” Butwhat troubled him in the long run was the feeling that he had let Schulberg down, and until the script was finished he kept sending Schulberg apologetic little suggestions of things that might be done with it. They were so battered and dirty when they reached New York that no hotel would take them in. Finally Sheilah, who had been waiting for Fitzgerald in New York, got him into Doctors Hospital; it was two weeks before he was well enough to return to Hollywood. I have based this account of the Winter Carnival trip largely on what Mr. Schulberg has told me and on his two articles about Fitzgerald, 'Fitzgerald in Hollywood,' The New Republic, March 31, 1941, and 'Old Scott,' Esquire, January, 1961. See also Beloved Infidel, pp. 271-72. In dealing with this episode Mr. Turnbull says that Mr. Schulberg was 'celebrity-conscious' and unable to 'help feeling a little superior to this derelict 'genius''(Scott Fitzgerald, pp. 296-97). I do not know the evidence on which Mr. Turnbull bases this unfavorable judgment of Mr. Schulberg, but it is perhaps worth reporting that during all the many times I have discussed Fitzgerald with him he has never shown anything but admiration and affection for Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald had not got a screen credit for his work on The Women and he had been replaced on Madame Curie after two months; the only screen credit he had was therefore the one for Three Comrades. His contract was not renewed, and he had to face a new situation. His first tentative plan was that “at present, while it is possible I may be on the Coast another year, it is more likely the work will be from picture to picture with the prospect of taking off three or four months in the year, perhaps even more, for literary work.” In January he was hired to do some revision on Gone With the Wind but found himself in the midst of a complicated row and made little impression. A little later he worked for a month or so with Donald Ogden Stewart on Air Raid. When that was shelved (for something called Honeymoon in Bali) even the idea of working from picture to picture became impossible to arrange and he began to drink heavily again.

In April he made an effort to start his novel but, though he talked about it a good deal to Perkins and Ober, he got little done; at the same time he was quarreling seriously with Sheilah over his drinking and very abruptly one day he decided to go east and take Zelda on a trip to Cuba. He was exhausted, drunk, and in low spirits and the trip ended calamitously. In Cuba, in a moment of confused heroism, he attempted to put a stop to a cock fight and was badly beaten for his pains. At the end of April he arrived back in New York in very bad shape. There his old friends the Cases, who managed the Algonquin where he was staying, got a doctor and a nurse for him. Again he was in Doctors Hospital forsome time before he was able to return to California, and it was July before he was able to get about as usual. “Almost every time I have come to New York lately,” he wrote Perkins, “I have just taken Zelda somewhere and have gone on more or less of a binge, and [Ober] has formed the idea that I am back in the mess of three years ago.” Ober was uncomfortably close to the truth.

But it was a truth Fitzgerald was very anxious to conceal, and he constructed an elaborate fiction about a recurrence of tuberculosis, complete with temperature readings, X-ray reports, and details about cavities. 'I think I can honestly say that the 1939 attack of T.B. was fictional. He was drinking heavily at the time and preferred to have as few people as possible know about it. Specifically, he tried to spare Scottie or rather to conceal from her the fact that he drank so much, so he referred to his confinement as T.B.' (See also Beloved Infidel, p. 278.) But though at that time he did not have tuberculosis, he was always anxiously expecting it to flare up (as it had briefly in December 1938). This anxiety was as persistent as his belief that whenever he went to the movies the person behind him was kicking the back of his chair. He even worried about Sheilah’s using his cup or towel. He had always been hypochondriacal when he was drinking and it was easy for him now to imagine he was tubercular; any steady drinking made him very ill, and any drinking at all became steady drinking. His way of bringing himself out of such bouts was drastic but perhaps necessary. He would get a doctor and nurses and put himself through a three- or four-day cure during which he was fed intravenously and tossed sleeplessly through the nights in retching misery. He emerged from such cures wan and shaken (See Beloved Infidel, pp. 210, 234-35, 269).

He was also soon in fresh financial difficulties. As early as the previous November he had borrowed from Perkins and in February he had begun to borrow against his insurance again. Even so he was in sore trouble by July. During May and June, when he had been struggling with the aftereffects of the Cuban trip, he had begun again to think of writing. He asked Harold Ober for details of the contemporary short-story market and took up once more his project for a novel. On the strength of these new intentions, he tried to borrow money from Ober, as he so frequently had in the past.

It was never easy for Ober to find the kind of money Fitzgerald always needed; often in the past he had deprived himself in order to provide it. Now, hoping he might force Fitzgerald to work really hard, he said he could no longer make advances on unwritten stories. Fitzgerald responded to this decision with indignation. After years of having Ober advance him the expected price of a story, he had come to feel that this was almost the normal mode of conducting business; perhaps, too, he suspected Ober’s motive and his pride was injured. The very fact that he did not wholly trust himself made him even more sensitive to such treatment. He had come very close to losing faith in himself with his failure at M-G-M and he desperately needed the encouragement of someone else’s belief in him. It was the rage of guilt and despair that made him write Perkins, “[Ober] is a stupid hard-headed man and has a highly erroneous idea of how I live, moreover he has made it a noble duty to piously depress me at every possible opportunity.” If, on the contrary, Ober guessed all too accurately how Fitzgerald was living, the angry sarcasm of “noble” and “piously” shows how much Fitzgerald hated anyone’s even suspecting his condition.

His answer to Ober combines a description of his inability to face what he believed to be Ober’s loss of faith in him with a generous acknowledgment of what he owed Ober from the past.

As I said in my telegram, the shock wasn’t so much at your refusal to lend me a specific sum … it was rather “the manner of the doing.”…

I don’t blame you…. my unwritten debt to you is terribly large and I shall always be terribly aware of it—your care and cherishing of Scottie during the intervals between school and camp in those awful sick years of ‘35 and ‘36. …

But Harold, I must never again let my morale become as shattered as it was in those black years….

I have a neurosis about anyone’s uncertainty about my ability that has been a principal handicap in the picture business…. One doesn’t change at 42 though one can grow more tired and even more acquiescent—and I am very close to knowing how you feel about it all: I realize there is little place in this tortured world for any exhibition of shattered nerves or anything that illness makes people do.

So goodbye and I won’t be ridiculous enough to thank you again.

From this time on Fitzgerald dealt directly—and far from effectively—with the magazine editors, mostly with Arnold Gingrich of Esquire who treated him very, very generously. In July, 1939, he turned out two stories, “Design in Plaster” and “The Lost Decade,” for Gingrich; they were his first stories since “Financing Finnegan,” written in June, 1937. Of the twenty-three stories he wrote from this time until his death all but one were sold to Esquire. Seventeen of the twenty-three belong to the series about Pat Hobby, Fitzgerald’s sardonic portrait of a broken-down script writer. “A complete rat” but not essentially a “sinister” character, he is what Fitzgerald in his worst moments saw himself becoming.

The six other stories of this period, together with the six he wrote in the spring of 1937 before going to Hollywood, constitute a distinct group; in them Fitzgerald faces the fact that he can no longer write the kind of popular love story he had made his short story reputation with and had to find a new subject and attitude. “It isn’t particularly likely,” he wrote one editor, “that I’ll write a great many more stories about young love. I was tagged with that by my first writings up to 1925. Since then… they have been done with increasing difficulty and increasing insincerity. … I have a daughter. She is very smart; she is very pretty; she is very popular. Her problems seem to me to be utterly dull and her point of view completely uninteresting. … I once tried to write about her. I couldn’t. So you see I’ve made a sort of turn.”

The stories in this group are not, of course, all equally good,but the vision projected in them is the vision of the late stories in Taps at Reveille and of the series of biographical sketches he had written in 1936 for Esquire. They are shorter than his earlier stories because of Esquire’s needs, with the result that Fitzgerald’s quiet, humorous acceptance of suffering and disaster is disentangled from the plots of his earlier stories about such feelings, and the brilliant, subtle movement of his final prose gets its full effect. We do not need to be told what to feel about Mr. Trimble of “The Lost Decade”; knowing him is enough. We are ahead of the doctor in “The Long Way Out” in wanting to get back to the subject of oubliettes. The condemnation of the Paris of the twenties in “News of Paris—Fifteen Years After” need never be made explicit because the shuffling moral attitude of the twenties toward their own conduct is, for all the grace and sympathy with which that conduct is presented, so completely implied by the events themselves. These stories, because of their brevity, are purer in motive and written more delicately and economically than any of Fitzgerald’s earlier stories.

Next chapter 16

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).