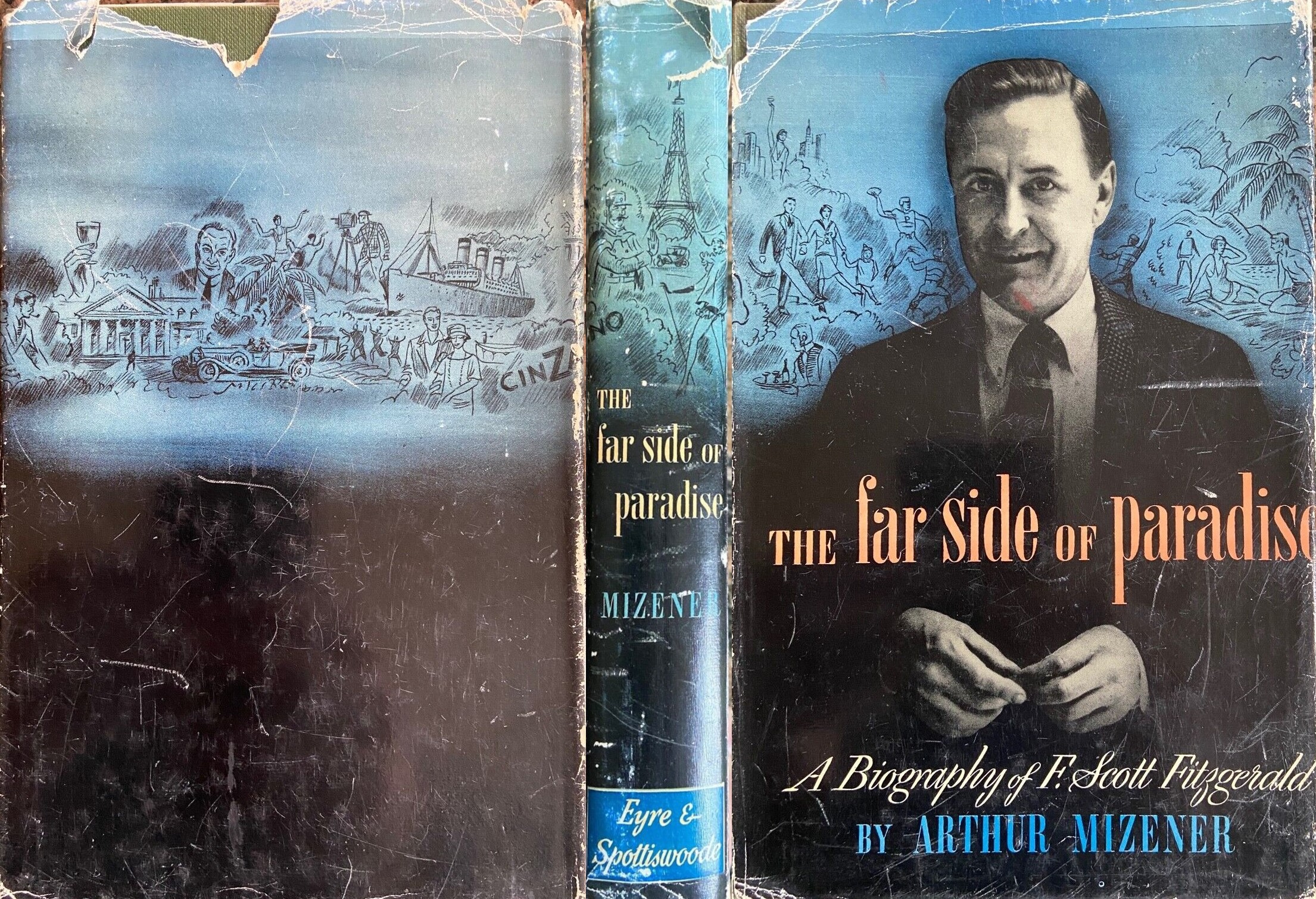

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter XVI

By the summerof 1939 he and Sheilah had made up their quarrel and Fitzgerald was beginning to get control of his drinking for considerable spells. But in the autumn, when Sheilah was nastily attacked by The Hollywood Reporter for something she had said on a lecture tour, he rushed violently to her defense, got very drunk, and tried to challenge The Reporter’s editor, W. R. Wilkinson, to a duel. In September he got a brief week of work at United Artists on Raffles, but he was still in great financial difficulties. Toward the end of that month, however, Littauer at Collier’s expressed a real interest in the novel Fitzgerald had had in the back of his mind since he had first met Irving Thalberg in 1931. Littauer agreed to pay $25,000 or $30,000 for the serial rights to this novel if Fitzgerald would submit fifteen thousand words and an outline that they liked. Collier's offer was for $2,500 for each installment of six or seven thousand words. As Fitzgerald planned the novel - though not as he actually wrote what he got written - this offer meant $20,000 or $25,000 for the complete serial. Later, however, Perkins estimated that Collier's might go to $30,000.

The possibility that he might be released from the drudgery of movie work and free to work on his novel for six months or more seemed miraculous to Fitzgerald, and he went to work with the old enthusiasm making notes and arranging the impressions of Hollywood that had been slowly gathering in his mind like the elements of a myth. He made hundreds of pages of notes; they constitute a minutely detailed, wonderfully perceptive portrait of a place and time, far richer than the small portion of these notes Fitzgerald got organized intothe six chapters of the novel he completed before he died. They show almost better than The Last Tycoon itself how intact his talent was despite his physical and nervous exhaustion.

As soon as he realized Collier’s was seriously interested, Fitzgerald sat down and wrote Littauer a letter outlining the story in detail and telling him what he hoped to make of it. How strongly he felt about it, however, is clearest from his letter to Scottie:

Scottina:

(Do you know that isn’t a nickname I invented but one that Gerald Murphy concocted on the Riviera years ago). Look! I have begun to write something that is maybe great, and I’m going to be absorbed in it for four or six months. It may not make us a cent but it will pay expenses and it is the first labor of love I’ve undertaken since the first part of “Infidelity.”… Anyhow, I’m alive again. …

He started to write with all the energy he could muster. “He didn’t rise at a given hour and plan the day’s work,” his secretary has said. “Insomnia more or less prevented such a routine…. Some days he worked more than others; some days he worked not at all. … He wrote in bed, in longhand. He preferred to write out narrative and dictated and even enacted dialogue, pacing the floor rapidly. He tired easily and didn’t have enough energy to devote a full day to writing, except under extreme pressure…. Once the plan for a story or idea was clear in his mind, he wrote rapidly. For instance, although it took him several years to accumulate and coordinate notes for The Last Tycoon, the actual writing time of the unfinished novel was only four months. He could do as many as a dozen pages in half a day.”

By the end of November he had completed six thousand words, probably the first chapter and the equivalent of oneinstallment instead of the two Littauer had asked for. Nonetheless, he sent it off to Littauer and asked for a decision. Since the story has reached only the flood in the studio back lot by the end of the first chapter, it is hardly surprising that Littauer wanted to defer verdict until further development of story. But Fitzgerald was uncontrollably impatient for encouragement and his financial difficulties were increasing—he had borrowed money to send Scottie back to Vassar. He abruptly cut off negotiations with Collier’s and wired Perkins: PLEASE RUSH COPY AIR MAIL TO SATURDAY EVENING POST. … I GUESS THERE ARE NO GREAT MAGAZINE EDITORS LEFT. But, like Collier’s, the Post wanted more to go on and there was no more, so that nothing came of this plan either.

As was always true when he was drinking, he was tense and easily driven to despair. “I’m so tired of being sick and old,” he wrote a friend when war broke out, “—would much rather be a scared young man peering out over a hunk of concrete or mud toward something I hate.” His decision to break off negotiations with Collier’s when all they had done was to suggest he follow the original arrangement was not a wise one; when his efforts to interest the Post failed, he grew even more bitter and depressed, and, as if he had to take it out on some one, he precipitated a desperate drunken quarrel with Sheilah during which he struck her and then threatened to kill her. When he finally sobered up he tried to apologize, but Sheilah could not forget that terrible quarrel for months. They finally made their peace in January, 1940, and from then until his death Fitzgerald remained sober. In April they gave up the house at Encino and Fitzgerald moved into an apartment in town near Sheilah’s.

Before he went back to work, he tried to make a quick profit from his idea and wrote a short story which is a simplified version of the love story of The Last Tycoon called, at first, “Pink and Silver Frost” and, later, “The Last Kiss.” It gives a queer, unsympathetic portrait of Kathleen, of which there is almost nothing left in The Last Tycoon. He could not sell this story so he went back to the novel, working on it as steadily as he could until April, when he took another movie job. By that time he had worked out in some detail nearly all of the six chapters which were completed at his death. He told his picture agent in May that he had written six chapters, but this statement can hardly be precise, since he spent a considerable part of November and December on the book, and during the last three weeks of his life he worked hard at it.

It had been a long time since he had had any picture work except the brief job on Raffles. At first he thought the reason was that he had stopped work for five months during 1939 and he wrote Scottie: “Sorry you got the impression that I’m quitting the movies—they are always there…. But I’m convinced that maybe they’re not going to make me Czar of the Industry right away, as I thought 10 months ago. It’s all right Baby—life has humbled me—Czar or not we’ll survive. I am even willing to compromise for Assistant Czar!” But by January he was frankly anxious. “Once Bud Schulberg told me that, while the story of an official blacklist is a legend, there is a kind of cabal that goes on between producers around a backgammon table, and I have an idea that some such sinister finger is upon me,” he wrote his agent.

In April, however, he found a picture job which, if it paid, according to his views, very little, was congenial and could be worked on outside the studio. In January Lester Cowan had bought the rights to “Babylon Revisited” for $800. “I sold ‘Babylon Revisited’ in which you are a character, to the pictures,” Fitzgerald wrote Scottie, “(the sum received wasn’t worthy of the magnificent story—neither of you nor of me—however, I am accepting it).” Cowan then offered Fitzgerald $5000 to make a script from it. Fitzgerald called the arrangement “a sort of half-pay, half ’spec’ (speculation) business… Columbia advances me living money while Iwork and if it goes over … I get an increasing sum. At bottom we eat—at top the deal is very promising.” He worked close to six hours a day getting the first draft out; this was an heroic effort in his condition, but he loved the story and called his work on it “more fun that I’ve ever had in pictures.” It appealed to him especially because he was now pretty well convinced that he “couldn’t make the grade as a hack—that, like everything else, requires a certain practised excellence.” What the excellence was he explained more carefully to his old friend Katherine Tighe: “…only in the last few months has life begun to level out again in any sensible way. The movies went to my head and I tried to lick the set up single handed and came out a sadder and wiser man. For a long time they will remain nothing more nor less than an industry to manufacture children’s wet goods.” He finished the script, called Cosmopolitan, at the end of June; there was a month and a half of revising and dickering to see if Shirley Temple could be interested in the part of Victoria (the Honoria of the story), and then the script was shelved “for one that has been made for the brave Laurence Olivier who will defend his country in Hollywood (though summoned back by the British Government). This affects the patriotic and unselfish Scott Fitzgerald to the extent that I receive no more money from that source…” Cosmopolitan was, except for some minor doctoring jobs, the last picture Fitzgerald did.

But Fitzgerald’s script is so good that its ghost keeps rising to haunt Mr. Cowan. In 1947 he asked a writer to revise it and when the writer said, “This is the most perfect motion-picture scenario I ever read. I don’t see why you want to revise it,” Mr. Cowan is reported to have said, “You’re absolutely right. I’ll pay you two thousand dollars a week to stay out here and keep me from changing one word of it.” During the summer of 1949 the script was again seriously considered for production.

Though Fitzgerald had been working steadily through the summer, he had not been well. “I can’t exercise even a little any more, I’m best off in my room,” he told Scottie. In his notes for The Last Tycoon he wrote: “Do I look like death (in mirror at 6 p.m.).” He did. He was very thin and his face was gray and delicate-looking. Only his eyes seemed alive, though his wit was as brilliant as ever when he had the physical and nervous energy to exercise it. “Do you want a picture of me in my palmy days or have you got one?” he wrote Scottie with his queer objectivity. (“If you don’t want this one send it back as thousands are clamoring for it,” he said when he sent the picture.)

With the money he collected from his picture work in September and October, he was able to devote himself to his novel and he determined to finish it. “I am trying desperately to finish my novel by the middle of December,” he wrote Zelda, “and it’s a little like working on Tender Is the Night at the end—I think of nothing else.” A few days later he was saying, “I am deep in my novel, living in it, and it makes me happy…. Two thousand words today and all good.”

In November he had what his doctor called a “cardiac spasm” while he was buying cigarettes in Schwab’s. How seriously he took it is shown by the fact that almost for the first time in his life he belittled instead of exaggerating an illness. “I’m still in bed but managing to write and feeling a good deal better. It was a regular heart attack this time and I will simply have to take better care of myself,” he wrote Scottie. Spending most of his time in bed, he got down to even harder work on The Last Tycoon. He knew exactly what he wanted to do: “I want to write scenes that are frightening and inimitable. I don’t want to be as intelligible to my contemporaries as Ernest who as Gertrude Stein said, is bound for the Museums. I am sure I am far enough ahead to have some small immortality if I can keep well.” Much of the actual writing of the book must have been done at this time.

It is not easy to be just to an unfinished novel; everyone tends to read it according to his established bias about the author. The reviewers found, if they were inclined that way, that The Last Tycoon provided “no evidence that [Fitzgerald] could have adjusted its themes into a beautiful articulated piece of craftmanship. … It would have sprawled…” Or they were convinced that “Had Fitzgerald been permitted to finish the book… there is no doubt that it would have added a major character and a major novel to American fiction.” On the whole, however, the reviews were serious and sympathetic. Even Margaret Marshall, who had said at the time of Fitzgerald’s death that Tender Is the Night was “a confused exercise in self-pity,” thought that The Last Tycoon “would assuredly have been a brilliant novel about Hollywood.” About the only representative of the old school of Fitzgerald reviewers was Time, which compared The Last Tycoon to Citizen Kane—though even this comparison may have been a compliment in Time’s judgment. The most penetrating reviews were Benet's and James Thurber's in the New Republic, February 9, 1942.

So far as it goes, The Last Tycoon justifies this burden of favorable opinion. It is true that Fitzgerald had a more ambitious and complicated judgment of his material in mind than he had ever tried to manage before; possibly he could not have pulled the various strands of this judgment together in the end, or perhaps he would have had to sacrifice the dramatic material of the novel to do so. But as far as he got, the evidence is that he would have succeeded in retaining his complex theme and still have managed to control the structure.

As he always did, he started here from direct observation. Even the flood with which he begins the Hollywood part of the novel actually occurred while he was there. It is no secret that Fitzgerald drew freely on his conception of Irving Thalberg for Stahr. At the time of Thalberg's death Fitzgerald had written a friend: 'Thalberg's final collapse is the death of an enemy for me, though I liked the guy enormously. ... I think ... that he killed the idea of either Hopkins or Frederick March doing 'Tender Is the Night.'' (See 'Crazy Sunday.') It is possibly less obvious that, back of every other character in the book, from Kathleen and Brady to the director Red Ridingwood and the superannuated star MarthaDodd, lay Fitzgerald’s acute observation of a real person. No wonder he wrote his daughter, “And I think when you read this book, which will encompass the time when you knew me as an adult, you will understand how intensively I knew your world…” Behind Fitzgerald's portrait of Cecilia is a good deal of Budd Schulberg's past as well as of Scottie. When he showed Schulberg the opening chapter of The Last Tycoon, he said, 'I sort of combined you with my daughter Scottie for Cecilia. ... I hope you won't mind'. He could have said as much for his observation of the movie world in which he had worked for three years. Personally withdrawn from it and yet close to it every day, he was like Cecilia, who “accepted Hollywood with the resignation of a ghost assigned to a haunted house. I knew what you were supposed to think about it but I was obstinately unhorrified.” It was the perfect situation for a writer who simultaneously knew experience as a participant and judged it as an uninvolved observer. Only now, perhaps for the first time in his life with complete understanding, he undertook to cultivate and control this double view of his subject.

His respect for the concrete reality of the life he was describing and his obstinate inability to be horrified by it are what make his description of that life better than any other in print. He knew exactly what he had to do to make it, with all its queerness, real: “actress—introduced so slowly, so close, so real that you believe in her. Somehow she’s first sitting next to you not an actress but with all the qualifications, loud and dissonant in your ear.” It is by this means that the wonderful, ordered but confusing series of scenes in Chapters III and IV—they were to be matched by a similar series at the end of the book—get their effect. At the center of this world lives Stahr with his “face that was aging from within, so that there were no casual furrows of worry and vexation but a drawn asceticism. …” Stahr is the last of the great paternalistic entrepreneurs, in the last, the most complicated, and the most fantastic of nineteenth-century capitalism’s empires. This was Fitzgerald’s deliberate and achieved intention, and in the unfinished part of the book, as Mr. Wilson points out, Stahr was to be defeated primarily by the fact that in the modern kind of capitalist enterprise, with its mechanical structure and its split between the highly organized management of the industry and the highly organized employees, there was no function for the brilliant individual who controlled everything by intelligence and understanding and “held himself directly responsible to everyone with whom he has worked.” “You’re doing a costume part and you don’t know it—the brilliant capitalist of the twenties,” Wylie White says to Stahr.

Yet, though Fitzgerald clearly felt this kind of man was doomed, and even rightly doomed, he admired his gifts more than any others; they were essentially gifts of humanity and imagination, and they were being used to organize, not a fictional world, but a real one. “I never thought,” Stahr tells Brimmer, “that I had more brains than a writer has. But I always thought that his brain belonged to me—because I knew how to use them. Like the Romans—I’ve heard that they never invented things but they knew what to do with them. Do you see? I don’t say it’s right. But it’s the way I’ve always felt—since I was a boy.” Fitzgerald, too, had felt it, since he was a boy. The dream of creating and managing a social enterprise had been part of his “great dream” since the days when he tried to take command of the games as a very small boy and had gone on to invent projects for the Gooserah Club and plays for the Elizabethan Dramatic Club.

A gift for organization and command had always been a characteristic of his heroes, though they had sometimes used that gift for trivial purposes. Amory Blaine had wanted “to pull strings, even for somebody else, or to be Princetonian chairman or Triangle president.” Gatsby had managed a great if illegal business enterprise, though it is far in the background of the novel (as when we hear Gatsby on the longdistance telephone: “I said a small town…. He must know what a small town is. … Well, he’s no use to us if Detroit is his idea of a small town….”). Dick Diver had used his gift to organize a social world for Nicole and her friends; “The enthusiasm, the selflessness behind the whole performance ravished [Rosemary], the technic of moving many varied types, each as immobile, as dependent on supplies of attention as an infantry battalion is dependent on rations, appeared so effortless…” But Stahr used this gift to manage a great and complex industry and to try to improve it. “From where he stood (and though he was not a tall man, it always seemed high up) he watched the multitudinous practicalities of his world like a proud young shepherd to whom night and day had never mattered.” He is Fitzgerald’s hero at his most mature and serious, applying his gifts to the central activity of American society.

Fitzgerald had not many illusions about business as such; it “is a dull game,” he said while he was writing the novel, “and they pay a big price in human values for their money”; and he suggested to Scottie that “Some time when you feel very brave and defiant [about her conservatism] and haven’t been invited to one particular college function read the terrible chapter in Das Kapital on The Working Day, and see if you are ever quite the same.” It was the authority and responsibility that fascinated him. He believed very deeply that “We can’t just let our worlds crash around us like a lot of dropped trays.”

Suppose—Stahr tells the pilot in the first chapter—you were a railroad man. You have to send a train through there somewhere. Well, you get your surveyors’ reports, and you find there’s three or four or half a dozen gaps, and not one is better than the other. You’ve got to decide—on what basis? You can’t test the best way—except by doing it. So you just do it.

“All leaders have felt that. Labor leaders, and certainly military leaders,” Brimmer tells Stahr when Stahr repeats this idea to him. Because Stahr was using his talent in a great and serious enterprise and because these similarities are evident to us as well as to Brimmer, we gradually see that for Fitzgerald his story is also a political fable. So far as he has gone he has handled this part of his story with great subtlety. Andrew Jackson, who like Stahr had faced a democratic crisis indomitably for all his faults and his illness and his social disadvantage, is presented to us cynically by Wylie White in the Hermitage scene in the first chapter. Wylie’s cynicism half conceals the difficult meaning of the past, its relevance to our present dilemma, as something or other does everywhere in the novel. There, at the Hermitage, Manny Schwartz, after telling Stahr that “when you turn against me I know it’s no use,” commits suicide. “He had come a long way from some Ghetto to present himself at that raw shrine. Manny Schwartz and Andrew Jackson—it was hard to say them in the same sentence. It was doubtful if he knew who Andrew Jackson was as he wandered around, but perhaps he figured that if people had preserved his house Andrew Jackson must have been someone who was large and merciful, able to understand.” “You sort of wish that Andrew Jackson would come out and welcome him in,” one of Fitzgerald’s notes adds. A little later, Prince Agge, deeply puzzled by Stahr, sees an extra dressed as Lincoln eating his lunch in the commissary. “This, then, he thought, was what they all meant to be.” “Stahr was an artist only, as Mr. Lincoln was a general, perforce and as a layman.” And in his notes Fitzgerald kept reminding himself to “show Stahr in Lincoln mood.” In the last part of the book Stahr was to go to Washington but to be ill and to see it clearly “only as he leaves.”

Fitzgerald’s writing is finer than any he had ever done before, and he had not made his final revision of any of it. All his old gifts are in the book. Its scenes are sharp, clean, and beautifully clear, as for instance when Stahr explains to Box-ley what movies are. Fitzgerald’s essential, poetic gift for getting at the quality and feel of a situation with muted figurative language never worked more unremittingly or more tactfully; in the scene on the plane with which the book opens, the stewardess “can always tell people are nice if they wrap their gum in paper”; the passengers make “the studied, unruffled exclamations of distaste that befitted the air-minded” when the plane dips; Schwartz stares at Stahr’s back “with shameless economic lechery” and speaks of his daughter “as if she had been sold to creditors as a tangible asset.” That gift places the startling, revealing, and touching detail just where it is needed:

Martha Dodd was an agricultural girl, who. had never quite understood what had happened to her and had nothing to show for it except a washed-out look about the eyes. …

“I had a beautiful place in 1928,” she told us, “—thirty acres, with a miniature golf course and a pool and a gorgeous view. All spring I was up to my ass in daisies.”

And there is the wonderful dialogue:

“Are you going to sing for Stahr?” Wylie said. “If you do, get in a line about my being a good supervisor.”

“Oh, this’ll be only Stahr and me,” I [Cecilia] said. “He’s going to look at me and think, ‘I’ve never really seen her before.’ “

“We don’t use that line this year,” he said.

”—Then he’ll say ‘Little Cecilia,’ like he did the night of the earthquake. He’ll say he never noticed I have become a woman.”

“You won’t have to do a thing.”

“I’ll stand there and bloom. After he kisses me as you would a child—“

“That’s all in my script,” complained Wylie, “and I’ve got to show it to him tomorrow.”

”—he’ll sit down and put his face in his hands and say he never thought of me like that.”

“You mean you get in a little fast work during the kiss?”

“I bloom, I told you. How often do I have to tell you I bloom.”

“It’s beginning to sound pretty randy to me,” said Wylie. “How about laying off—I’ve got to work this morning.”

Throughout the book there is the quiet, powerful prose of Fitzgerald’s last period. There are no costume-jewelry comparisons or appeals to feelings outside the context of the narrative such as occasionally marred his earlier work. The feelings always belong to the people and the events; they are never forced on them, never asserted for their own sake.

But whether he could have fulfilled the promise of this beginning we can never be sure. Like so much else in his life, his heroic effort to finish his last novel came too late; and the luck which might have kept him alive until he had finished was not with him. He had predicted to Perkins in the middle of December that he could complete a first draft by January 15, and at the rate he was going he might have done so; on December 20 he had completed the first episode of Chapter VI. But that night—it was a Friday—as he and Sheilah were leaving the Pantages Theatre after seeing This Thing Called Love, he had another attack, so severe that he managed to get out of the theatre only with Sheikh’s help; that frightened her: he had never let her help him before. “I feel awful,” he said, “—everything started to go as it did that night at Schwab’s.” But he slept well that night and seemed himself the next morning. After lunch, while they waited for the regular visit of the doctor, Fitzgerald sat making notes on the margin of an article about the Princeton football team. Suddenly he started up from his chair, clutched the mantel for a moment, and then fell to the floor. In a few moments he was dead.

He was buried with a flurry of ironies even thicker than he had himself dared to devise for Gatsby. His body was laid out in an undertaker’s parlor on Washington Boulevard “which,” as one observer remarked, “—to Beverly Hills—is on the other side of the tracks in downtown Los Angeles.” He was not placed in the chapel but in a back room named the William Wordsworth room; no doubt it seemed to the undertaker the appropriate place for a literary man. Almost no one came to see him; one of the people who did said that

he was laid out to look like a cross between a floor-walker and a wax dummy in the window of a two-pants tailor. But in technicolor. Not a line showed on his face. His hair was parted slightly to one side. None of it was gray.

Until you reached his hands, this looked strictly like an A production in peace and security. Realism began at his extremities. His hands were horribly wrinkled and thin, the only proof left after death that for all the props of youth, he actually had suffered and died an old man.

His old friend Dorothy Parker is said to have stood looking at his body for a long time and then, without taking her eyes off him, to have repeated quietly what “Owl-eyes” said at Gatsby’s funeral: “The poor son of a bitch.” This story has been reported to me as coming from Alan Campbell, who was then Dorothy Parker's husband.

His body was shipped to Baltimore for burial. He had always wanted to be buried with his father’s family in the Catholic cemetery at Rockville, Maryland. But there were difficulties about this plan: his books were proscribed and he had not died a good Catholic. Despite the efforts of his friends to overcome these difficulties, the Bishop refused to allow him to be buried in hallowed ground. The funeral itself was a very simple one. When Fitzgerald had made his will in June, 1937, full of optimism about the fortune he was to make in Hollywood, he had written: “Part of my estate is first to provide for a funeral and burial in keeping with my station in life.” But later he canceled “for a funeral” and inserted in pencil “the cheapest funeral.” Then he added at the end of the paragraph: “The same to be without undue ostentation or unnecessary expense.”

The services were held in a funeral parlor in Bethesda on December 27. Scottie was there, and Fitzgerald’s cousins from Norfolk, the Abeles and the Taylors, and Zelda’s brother-in-law, Newman Smith, from Atlanta. There were old friends like Max Perkins and Harold Ober and the Murphys from New York and college friends like Ludlow Fowler and Judge Biggs and a number of others who lived in Baltimore. One of those present estimated that there were all of thirty or forty people there. Miss Graham was not one of them. He was buried in the Rockville Union Cemetery. It was as near as he was allowed to be to his father, beside whose grave he had stood almost exactly ten years before thinking how “very friendly [it was] leaving him there with all his relations around him.”

***

Not long before he died Fitzgerald scribbled on an odd scrap of paper a few imperfect lines for a poem he never got time to finish. As if conscious to the last of a need to tell his story, he was writing his own epitaph.

Your books were in your desk

I guess and some unfinished

Chaos in your head

Was dumped to nothing by the great janitress

Of destinies.

The novel he wanted so desperately to complete was unfinished; the reputation in which he found his justification was only a faint echo (all his life he saved clippings about himself; at the end there were only a few scattered sentences from The Hollywood Reporter to be clipped); and he was, he knew, dying. Like Gatsby, who felt that if Daisy had loved Tom at all “it was just personal,” Fitzgerald loved reputation, the public acknowledgment of genuine achievement, with the impersonal magnanimity of a Renaissance prince. He lived, finally, to give that chaos in his head shape in his books andto see the knowledge that he had done so reflected back to him from the world. He died believing he had failed.

Now we know better, and it is one of the final ironies of Fitzgerald’s career that he did not live to enjoy our knowledge. “You can take off your hats, now, gentlemen,” Stephen Vincent Benêt wrote when The Last Tycoon appeared in 1941, “and I think perhaps you had better. This is not a legend, this is a reputation—and, seen in perspective, it may well be one of the most secure reputations of our time.”

On March 11, 1947, Highland Hospital burned down. Zelda Fitzgerald, who was on the top floor, was trapped and burned to death. She was buried beside Fitzgerald in the small-town quiet of the Rockville Cemetery. There is a common headstone.

The End

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).