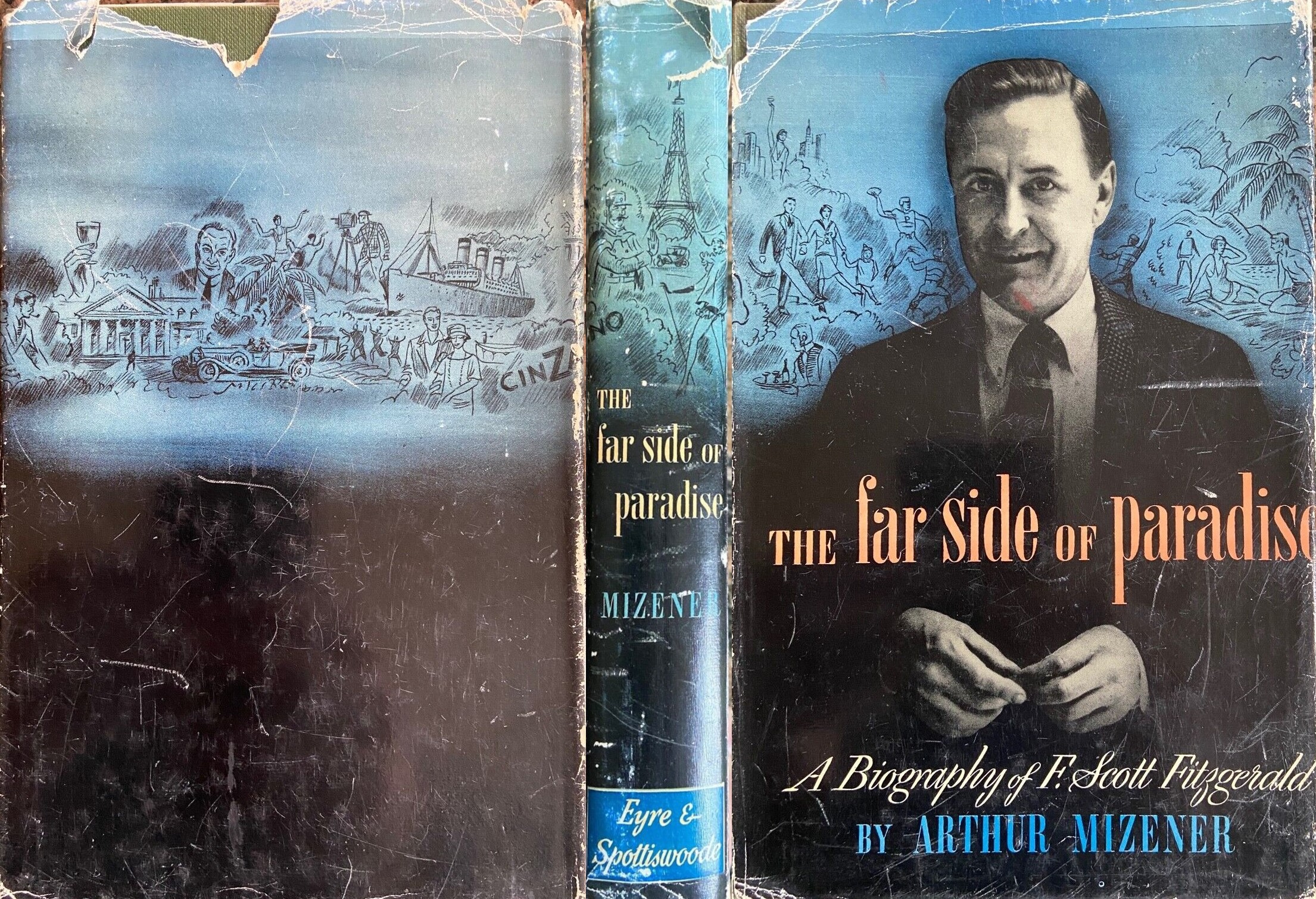

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter XIV

Fitzgerald waited anxiously for the reviews of Tender Is the Night. It was not just a matter of being taken seriously or even of making money now. It was a question of his ability to believe in himself. When the character of the reviews and the sales—Tender Is the Night sold around thirteen thousand copies—became clear, his morale dropped lower than it ever had before. This was the biggest battle he had lost yet.

In April he had started on a project which was to occupy him off and on for a year or more and, sporadically, for the rest of his life. This was a novel about medieval life which was to take a young man called Phillipe from about 880 to about 950; he was to participate in the founding of France as a nation and, in his old age, to watch the consolidation of the feudal system. It was to be called The Count of Darkness. Fitzgerald’s plan was that “it shall be the story of Ernest” and his hope that “just as Stendahl’s portrait of a Byronic man made Le Rouge et Noir so couldn’t my portrait of Ernest as Phillipe make the real modern man.” In the end, he got four long installments of this story written. They are as bad as anything Fitzgerald ever wrote, and there is good reason to believe that Red Book bought the four installments partly in an effort to help him (The delay in the publishing of the last installment bears out the story. Herbert Mayes bought two unpublished Gwen stories for Good Housekeeping in 1936 'when I knew he was in financial difficulties... They were poorly handled and I never had any intention of publishing them.'). They are the clearest example there is of what Fitzgerald’s work could be when he was not writing out of personal experience.

He was working now in a nightmare of discouragement about his writing and of despair about Zelda—she grew worse rather than better all year—and of worry over finances. In June he spent what he called “a crazy week in New York” and collapsed when he got home. He was in the hospital for some time, got out in July, and then had to go back again. He was beginning to find himself in dangerous financial straits. “The bills really begin,” he noted in his Ledger in July; in September it was “Finances now serious” and in November “Debt bad.”

In September he tried, very tentatively, a love affair. It was an effort to get started living again. It took him away from Baltimore into Virginia on frequent visits and he eventually made a story out of the places he visited and his feelings about this relation. He tried to believe he was pulling himself together, too. “I behaved myself well on all occasions but one, when I did my usual act, which is—to seem perfectly all right up to five minutes before collapse and then to go completely black.” But the love affair was no good, and by January, 1935, he was noting that he was “tiring of——,” and in April, “Good-bye to——” This failure he thought was his own fault and it discouraged him further. For sometime afterwards he kept trying tentative love affairs, from brief encounters on weekends to somewhat more permanent affairs. None of them was very successful. Much as Fitzgerald felt he was missing something in life—and he could never bear to miss anything—by not being able to enjoy its casual pleasures, the very intensity that made him hate to miss anything made it impossible for him to have a casual love affair. “Oh, I’ve had all the fun,” he once said, “but in my heart I can’t stand this casual business. With a woman, I have to be emotionally in it up to the eyebrows, or its nothing. With me it isn’t an affair—it must be the real thing, absorbing me spiritually and emotionally…. Silly, isn’t it? Look at the fun we miss!”

By fall he was in a mood of deep depression. Perkins came to Baltimore to see him and he made an effort to rally. After Perkins had gone Fitzgerald wrote him, “The mood of terrible depression & despair is not going to become characteristic & I am ashamed and felt very yellow about it afterwards. But to deny that such moods come increasingly would be futile.” A couple of weeks later he was saying, with one of his revealing non sequiturs, “… you might have taken literally what I said. I am, in point of fact, never really discouraged; nevertheless to communicate it were a crime.” And the façade came down with a crash a month later: “When the hell did you and Ober get together on my physical habits? It seems to me I’ve had so many—“but before he sent the letter to Perkins he tore up the rest of it. During this whole time his devoted friend Doctor Benjamin Baker was trying to help him. They had an agreement that Fitzgerald would call Doctor Baker whenever he felt tempted to drink. Once Fitzgerald called him from New York. “Ben,” he said, “I’m going to take a drink.” Doctor Baker begged him to hold off for half an hour, and Fitzgerald said he would try. During that half-hour Doctor Baker got hold of a friend in New York who gave Fitzgerald half a dozen secconal tablets and put him on the train for Baltimore, where Doctor Baker met him and took him to the hospital. But these methods were only stop-gap. That Christmas Eve Zelda was well enough to come home overnight and they had a little tree. But she soon grew worse again.

For the next month he was struggling with the proofs of Taps at Reveille. As usual he worried about the title; 'women,' he thought, 'couldn't pronounce it.' He tried to get Perkins to substitute one of several others, the best of which was Last Night's Moon. The book was once advertised as Tales of the Golden Twenties (New York Times, June 17, 1934). Fitzgerald as usual disliked the jacket: 'Some one who can't draw as well as Scottie,' he said. It gave him more trouble than any of his other books of short stories. In the first place Perkins, who was a great admirer of the Basil stories, wanted him to make a separate book of them—there were nine of them, quite enough for a short volume. But he would not publish the stories without revision, and the best Perkins could do was to get him to revise five for Taps.

In the second place, since Fitzgerald had not published a volume of short stories since 1926, he had an accumulation of sixty-one stories to select from. He finally chose ten, in addition to the Basil and the Josephine stories which fill half the book. They may not have been the ten best stories he could have chosen: Fitzgerald was a shrewd, even brutal critic of his own work, but not always a judicious one. He tended, like all writers, to overrate his most recent work. While Taps at Reveille was in hand—it was put in hand in October, 1934—he dropped “A New Leaf” and added “Her Last Case” and “The Fiend.” Then, when the book was in proof, he dropped “Her Last Case” in favor of “The Night of Chancellorsville.”

The stories in Taps at Reveille fall into two distinguishable groups chronologically, and this division is important because it represents a division in the character of his work. The first group—these are the dates of the writing of the stories, not necessarily of their publication—includes the Basil stories (1928) and the Josephine stories (1930), “A Short Trip Home” (1927), “The Last of the Belles” (1928), “Majesty” (1929), “Two Wrongs” (1929); the second includes “Babylon Revisited” (December, 1930), “Crazy Sunday,” “Family in the Wind,” “One Interne” (all 1932). The first group of stories are the work of the Fitzgerald who was clinging to his old attitudes and convictions; they are the work of the superficially ironic but fundamentally romantic young man. Their sadness is the sadness of the lost past, like that of the best stories in All the Sad Young Men;their irony is an acute awareness, an acceptance, of its distance and difference from the present. This irony is everywhere in the best of the stories, unobtrusive but perfectly in control of the evoked sentiment for the past. It may control the main intention of the story, as in “The Last of the Belles,” when Andy, standing in the deserted camp, thinks of wartime Tarleton and the young Ailie Calhoun: “All I could be sure of was this place that had oncebeen so full of life and effort was gone, as if it had never existed, and that in another month Ailie would be gone, and the South would be empty for me forever.” It may control the smallest details, as when Basil, having ordered “a club sandwich, French fried potatoes and a chocolate parfait” at the Manhattan Hotel, watches “the nonchalant, debonair, blasé New Yorkers” and wanting another chocolate parfait, is “reluctant to bother the busy waiter any more.” It is this balance which gives these stories their power and charm. Possibly 'Two Wrongs' is a partial exception to the generalization in the text. It is, of course, a history of Fitzgerald's own mental and emotional career done in terms of the theatre rather than the novel and it has some of the qualities of his later stories. It was probably written just after his attack of tuberculosis in 1929 (the story was written during October and November of that year) and out of his awareness of how orderly Zelda's life was compared to his own.

The other, smaller group of stories differ from these in an important respect. They were all written after Zelda’s collapse and Fitzgerald’s confrontation of his own deterioration. In them the past has lost its importance. In the first group of stories the main feeling is the sadness of loss and remembrance; the things past had been in themselves happy. But in these stories the past is used only for exposition; they are about the grim present. The first, and perhaps the finest, is “Babylon Revisited,” an attempt to come to grips with all he felt about Zelda’s collapse and his considered love and responsibility for Scottie. A more representative one is “Family in the Wind.” Characteristically Fitzgerald described it as “based on his experiences in the tornadoes that recently swept part of Alabama.” But the story’s value is a result of his attempt to adjust to the wreckage of his own career and his present condition. These feelings are complicated. There is the feeling of injustice, of punishment over and above the crime (a difficult feeling to handle because it is so close to self-pity). There is the acceptance of what is his own doing, including the loss of his fellows’ respect, which was very important to Fitzgerald, even though his destruction of it was sometimes wanton. There is the awareness of “his own moribund but still struggling will to power.” And there is the sense of the pity and irony of anyone’s being in this position whatever the causes.

“Family in the Wind” thus provides an early version of the state of mind which Fitzgerald was going to describe with grimly comic exaggeration three years later in “Pasting It Together,” that “spiritual ‘change of life’ “which began as “a protest against a new set of conditions which I would have to face and a protest of my mind at having to make the psychological adjustments which would suit this new set of circumstances.” As always this understanding and acceptance came first as an act of the imagination, an effort to conceive as fiction this fundamentally different kind of experience and his role in it.

I’m very happy, or very miserable—says Forrest Janney in “Family in the Wind”—I chuckle or I weep alcoholically and, as I continue to slow up, life accommodatingly goes faster, so that the less there is of myself inside, the more diverting becomes the moving picture without. I have cut myself off from the respect of my fellow man, but I am aware of a compensatory cirrhosis of the emotions. And because my sensitivity, my pity, no longer has direction, but fixes itself on whatever is at hand, I have become an exceptionally good fellow—much more so than when I was a good doctor.

In February, when the last decision about Taps at Reveille had been made and the final proofs read, Fitzgerald turned once more to his personal problem. It seemed to him so overwhelming that he suddenly decided to flee, not so much from himself as to the privacy in which he could confront himself. He went south, first to Tryon and, later in the year, to Hendersonville, North Carolina, a little resort town of about twelve thousand people near Asheville. Here he holed up in a cheap hotel and tried to put himself on the wagon—“on Thursday 7th (or Wed. 6th at 8:30 p.m.)” as he noted in his Ledger. For a month he hung on there suffering from cirrhosis of the liver and trying to stick to beer. “One harrassed and despairing night I packed a brief case and went off a thousand miles to think it over. I took a dollar room in a drab little town where I knew no one and sunk all the money I had with me in a stock of potted meat, crackers and apples.” “I can still see his room,” said Nora Flynn, a friend who lived in Tryon and tried to help him, “with collar buttons on the bureau, and neckties hanging from the light fixture, and dirty pajamas all over.” But Mr. and Mrs. Flynn did not know how desperate his situation was. While he was staying in Hendersonville he made a little note of exactly how he lived.

I am living very cheaply. Today I am in comparative affluence, but Monday and Tuesday I had two tins of potted meat, three oranges and a box of Uneedas and two cans of beer. … It was fun to be poor—especially if you haven’t enough liver power for an appetite. But the air is fine here and I liked what I had—and there was nothing to do about it anyhow because I was afraid to cash any checks and I had to save enough for postage for the story. But it was funny coming into the hotel and the very deferential clerk not knowing that I was not only thousands, nay tens of thousands in debt, but had less than 40 cents cash in the world and probably a $13. deficit at my bank. … I haven’t told you the half of it, i.e. My underwear I started with was a pair of pajama pants—just that. … I washed my two handkerchiefs and my shirt every night, but the pajama trousers I had to wear all the time and I am presenting it to the Hendersonville Museum…

Both Mrs. Flynn and her husband were kind and gentle with him. He never forgot their generosity and always remembered “Nora’s gay, brave, stimulating, ‘tighten up your belt, baby, let’s get going. To any Pole.’ ““I am astonished sometimes,” he added, “By the fearlessness of women, the recklessness—like Nora, Zelda… But it’s heartening when it stays this side of recklessness.” She did her best to cheer Fitzgerald but, as he said, “of all natural forces, vitality is theincommunicable one…. You have it or you haven’t it, like health or brown eyes or honor or a baritone voice. … I could [only] walk from her door, holding myself very carefully like cracked crockery, and go away into the world of bitterness, where I was making a home with such materials as are found there.” She told him her own story, “old woes of her own… and how she had met them, over-ridden them, beaten them.” During March he succeeded in making a story, “The Intimate Strangers,”; out of those old woes, one of the last romantic love stories he attempted.

By the end of the month he was back in Baltimore, still “very sick,” to find Zelda much worse; and as always there were his “terrible debts.” Taps at Reveille was not going well. Except for a brilliant review by William Troy in The Nation, the reviewers talked about “avowed pot-boilers,” and a “subject matter that clings desperately to the knee-skirts of the jazz age.” The book sold only a few thousand copies. There was a month of struggling with Zelda’s fresh breakdown, but by, the middle of April the worst was over and he wrote Perkins: “Zelda, after a terrible crisis, is somewhat better.” “I am, of course,” he added pathetically, “on the wagon as always…” It was not until three years later that he could say of this time that “the things that were the matter with me were so apparent, however, that I did not even need a psychoanalyst to tell me that I was being stubborn about this (giving up drinking) or stupid about that (trying to do too many things)…”

In May matters were brought to a crisis for him by an attack of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis had been half a disease and half an excuse with Fitzgerald for years; it had even been suspected in his childhood. He had probably had a mild attack when he went to New Orleans in 1919. In 1929, the medical records show, he had had a considerable hemorrhage; he did nothing about it, but the healed scar showed clearly in an X-ray taken in 1932. Now the pictures showed a real cavityand Doctor Baker sent Fitzgerald off to a top specialist, Doctor Paul Ringer, in Asheville.

I had sat in the office of a great doctor—he wrote later—and listened to a grave sentence. With what, in retrospect, seems some equanimity, I had gone about my affairs in the city where I was then living, not caring much, not thinking how much had been left undone, or what would become of this and that responsibility, like people do in books; I was well insured and anyhow I had been a mediocre care-taker of most of the things left in my hands, even of my talent.

Because he was frightened of the effect on his earning capacity if it were known he was tubercular, he persuaded Doctor Ringer to take care of him while he lived at the Grove Park Inn at Asheville. The arrangement was not successful because Fitzgerald would not obey instructions, and it had to be discontinued. He was vague to Perkins—“I am closing the house and going away somewhere for a couple of months,” he wrote—and even told close friends only that he was leaving “for a protracted sojourn in the country… still seeking to get back the hours of sleep that I lost in ‘33 and ‘34… I hate like the devil to leave [Zelda] but it is doctor’s orders.”

“And then suddenly, surprisingly, I got better”—at least the tuberculosis subsided—“and cracked like an old plate as soon as I heard the news.” He had suddenly reached that state which he called “emotional bankruptcy”—“an over-extension of the flank, a burning of the candle at both ends; a call upon physical resources that I did not command, like a man overdrawing at his bank.” He could no longer believe in any of the things that had made him fight up to now, “a feeling,” he called it, “that I was standing at twilight on a deserted range, with an empty rifle in my hands and the targets down. No problem set—simply a silence with only the sound of my own breathing”—watching “the disintegration of [my] own personality.”

For the rest of the summer he made his headquarters inAsheville, going to Baltimore and New York occasionally. Late in the summer he was in a hospital in New York and a month later he had a more serious collapse back in Baltimore and spent a longer stretch in the hospital. After he got out he decided to give up the house on Park Avenue and take an apartment in the Cambridge Arms—“the attic, Cambridge Arms,” he used to head his letters.

It was a time when his friends worried about his daughter’s living with him. She was fourteen years old and it would be another year before she went away to school. His friends, especially his agent, Harold Ober, took over a large part of the responsibility for her during the next few years and she lived mostly with them when she was not at school or camp. Fitzgerald had curiously old-fashioned views of how children should be raised and a special feeling of responsibility for his daughter because she had no mother—a feeling which was only increased by his awareness of what he put her through when he was drinking. He was often ridiculously severe. His attitude shows in the stories he wrote about her, despite the gloss of liberality he gave his own conduct. When it was not so adorned it was touching and—from Scottie’s point of view—probably intolerable. “Don’t,” he would implore his cousin Ceci when Scottie was visiting in Norfolk—

Don’t let her go out with any sixteen year old boys who have managed to amass a charred keg and an automobile license as their Start-in-Life. Really I mean this. My great concern with Scottie for the next five years will be to keep her from being mashed up in an automobile accident…. P.S. I mean that, about any unreliable Virginia boys taking my pet around…. Scottie hasn’t got three sisters—she has only got me. Watch her please!

In addition to this intensified version of the usual parental anxieties, he suffered from continual fear that Scottie might, like him and like the Ginevra King he had imagined for the Josephine stories, become emotionally bankrupt. “Our danger,” he would write her, “is imagining that we have resources—material and moral—which we haven’t got…. Do you know what bankruptcy exactly means? It means drawing on resources which one does not possess…. But I think that, like me, you will be something of a fool in that regard all your life, so I am wasting my words.” Nevertheless he could not resist wasting them: a year and a half later he was telling her exactly the same thing: “The real handicap for a girl like you would have been to have worn herself out emotionally at sixteen.”

Then he would remember the way he had treated her when he was tired and overwrought or drunk and write penitently to her (age fifteen), “I think of you constantly and if I ever prayed it would be that the irritations, exasperations and blow ups of the past winter wouldn’t spoil the old confidence we had in each other.” The severe father, the difficult alcoholic, and the man who loved his child intensely and wanted her confidence continued to alternate all through Scottie’s adolescence.

He struggled through the old ritual of having Zelda at home for Christmas that winter but during February and March he was in the hospital several times. “Me caring for no one and nothing,” he noted in his Ledger. At the same time his work began to decline in quality. Except for the three crack-up articles he wrote at the end of 1935 in a serious attempt to get at his own state of mind (“The Crack-Up,” “Handle with Care,” and “Pasting It Together”), he had been turning out nothing but mediocre work for a year or more; it was remarkable that he turned out even printable work considering the circumstances. But now his fiction began, for the first time in years, to be rejected. He grew anxious over the apparent failure of his creative power, for it fitted altogether too well with his theory of emotional bankruptcy to be taken lightly. As late as the middle of 1937, he wrote his friend and secretary, Martha Marie Shank: “Went to New York, wrote two stories on the spot and sold them on the spot. Can it be that the climate here [this letter was written from Tryon] isn’t good for work?” Some sense of what he had to do set him writing a series of autobiographical pieces during these early months of 1936, pieces which could exploit the new personality toward which he was moving and save him the hopeless struggle to fake the old optimistic excitement which had been the making of his popular fiction in the past. (“It grows harder to write now,” he said wryly, “because there is so much less weather than when I was a boy and practically no men and women at all.”) They brought him, with the exception of the crack-up series, less fame and—at $250 apiece from Esquire—much less fortune than he had earned in the past. But they are beautifully written little sketches, and through them he gradually worked out fully the attitude which had first appeared in Taps at Reveille and was to dominate the stories he wrote during the rest of his life.

Though he was convinced, as one close observer put it, that “his writing ability had left, or was leaving, him for good,” Fitzgerald’s crack-up was not so final as he supposed. But, as he remarked of a disaster earlier in his life, “A man does not recover from such jolts—he becomes a different person and, eventually, the new person finds new things to care about.” If Fitzgerald was not, as his father had been, “a failure the rest of his days,” he was a scarred man whose success was of a very different order from what the man he had been before he went emotionally bankrupt had desired and, to a large extent, achieved. For the rest of his life he continued to think of himself as living on what he had saved out of a spiritual forced sale. “The price was high,” he said, “right up with Kipling, because there was one little drop of something—not blood, not a tear, not my seed, but me more intimately than these, in every story, it was the extra I had. Now it is gone and I am just like you now.”

In April he decided to put Zelda in a sanitarium called Highlands, near Asheville; it was to be her permanent headquarters for the rest of his life. In July he gave up the apartment in Baltimore and moved temporarily to a hotel. Here Zelda was allowed to come for a weekend visit. His pity for her, when they were separate and he allowed himself to brood about it, was very deep. “I think I feel [the whole tragedy of Zelda] more now than at any time since it’s inception. She seems so helpless and pitiful,” he said about this time. But he was himself in such a nervous condition that he could seldom endure for more than a few hours the strain of living in the limited world she inhabited. This time he got drunk and they quarreled. Zelda walked out of the hotel and when the friend Fitzgerald had called for help arrived he found Fitzgerald carefully emptying her suitcase and tearing up her clothes, slowly, piece by piece. He refused to discuss where Zelda might have gone. After a long search the friend found her at the station, exquisitely dressed, a thoroughly sophisticated woman, except that she was wearing a hat like a child’s bonnet with the strings carefully knotted under her chin. She was reading the Bible. Though it was hours before train time, she insisted quietly that she had to remain there because she had to get back to Highlands. She was penniless, and their friend had to find Fitzgerald again, get Zelda’s fare from him, and take it to Zelda at the station.

All too frequently their visits ended so. Fitzgerald would plot and plan endlessly in advance to make a little vacation from Highlands as perfect as possible for Zelda: he once interrupted Dean Gauss in the midst of Commencement exercises to have him look at a dress he had bought Zelda in New York and was taking to her. But when he was actually with her he would go to pieces. “I added to the confusion,” he said of another trip, “by getting drunk, whereupon she adopted the course of telling all and sundry that I was a dangerous man and needed to be carefully watched… Onthe boat coming up from Norfolk… I had some words with the idiotic trained nurse… all this isn’t pretty on my part, but if I had been left alone, would have amounted to a two day batt.”

Sometimes he would make a success of such a visit. Their best times were while he was living at Asheville in 1936 and 1937; living in comparative quiet there, he was better than he had been for some time, and Zelda improved after she got to Highlands to the point where he was much encouraged. “Your mother,” he wrote his daughter, “looks five years younger and prettier… Maybe she will still come all the way back. So things are not as blue-looking as they have been this past winter and spring.” This improvement was, of course, comparative. On several occasions Fitzgerald took Zelda back to Tryon with him to gatherings at the Flynns or the Bannings. Once, one of the guests reported, “She came in looking like Ophelia, with water lilies she’d bought…. Wine was served and she drank it in an eager gulp and right away it set her off.” Fitzgerald drew her quietly into a corner and began a little fairy story in which she was a princess in a tower and he her prince; gradually she came to herself. Mrs. Flynn herself commented on another occasion when Zelda came in looking old and ill and, after walking about just touching things for a while, started to dance. “I shall never forget,” she said, “the tragic, frightful look on [Scott’s] face as he watched her…. They had loved each other. Now it was dead. But he still loved that love and hated to give it up—that was what he continued to nurse and cherish.”

On one such occasion in July he took Zelda swimming near Asheville. Feeling better than he had in a year and a half, “I thought I would be very smart and do some diving.” It went all right for a little, but then, “trying to show off for Zelda,” he ventured a dive from the fifteen-foot board and, while he was still in midair, tore the muscles of his shoulder so badly that he ended with his arm dangling an inch or two out ofthe socket (Fitzgerald wrote dozens of accounts of this accident. I have quoted from letters to Frances Fitzgerald Lanahan, July 31, 1936, and to C.O. Kalman, September 19, 1936.). The shoulder started to heal after a couple of weeks but then Fitzgerald, soaking with sweat on a very hot night, tripped over the raised platform of the bathroom. It was four o’clock in the morning and, nearly helpless in his cast, he took three quarters of an hour to crawl to the telephone and get help. He caught cold and developed “Miotosis” (a form of arthritis) in his shoulder and had to go back to bed for several weeks more. It was the middle of September before he could get around again.

The worst consequence of this accident was its effect on his morale. Putting it in the best light he could, Fitzgerald described this effect by saying: “I had been seriously sick for a year and just barely recovered and tried to set up a household in Baltimore which I was ill equipped to sustain. I was planning to spend a fairly leisurely summer, keeping my debt in abeyance on money I had borrowed on my life insurance… To make a long story short, I was on my back for ten weeks, with whole days in which I was out of bed trying to write or dictate, and then a return to the impotency of the trouble.” What happened was that, out of pain and boredom and to get stimulation for his work, he began to drink again. Something of what he felt can be deduced from the story he wrote about this accident called “Design in Plaster,” and something more from the fact that during this time he twice attempted to commit suicide. Once his secretary came in and found him lying on the bed in a darkened room and staring at the ceiling. She sat down on the chair beside the bed and said: “Scott, what is going to become of you?” He looked at her for a moment in a way she still remembers with terror and then said quietly, “God knows.” It was truly a time when, as he said, “it is always three o’clock in the morning, day after day.”

On September 24, his fortieth birthday, an enterprising and inhuman reporter came to interview him. He found Fitzgerald in his room, up and about but still under nurse’s care,and noted “his jittery jumping off and onto his bed, his restless pacing, his trembling hands … his frequent trips to a highboy, in a drawer of which lay a bottle.” Each time Fitzgerald poured a drink into the measuring glass on his bedside table, he would look appealingly at the nurse and ask, “Just one ounce?” As time went on (“Much against your better judgment, my dear,” he was now saying to the nurse) he got franker. “A writer like me,” he said, “must have an utter confidence, an utter faith in his star. … I once had it. But through a series of blows, many of them my own fault, something happened to that sense of immunity and I lost my grip.” When the reporter asked him about his own generation, he said, “Some became brokers and threw themselves out of windows. Others became bankers and shot themselves…. And a few became successful authors.” His face twitched. “Successful authors!” he cried. “Oh, my God, successful authors!”

When all this appeared in print Fitzgerald was frightened—for its effect on his market—and hurt; “Martha Marie,” he said to his secretary, “it nearly broke my heart.” “None of the remarks attributed to me did I make to him. They were taken word by word from the first ‘crack-up’ article…” he said. “I had a temperature of 103 with arthritis, after a ten weeks’ siege in and out of bed. He was an s. o. b. and I should have guessed it.”

This interview shows Fitzgerald in the state of mind he used for his story “An Alcoholic Case,” which he wrote in December. But he was still capable of his old charm and excitement when properly appealed to. At Max Perkins’ insistence Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, who was spending the summer in the Carolina mountains working on The Yearling, came to see him. Her recollection of the occasion is vivid:

He was exhilarated. He talked of his own work. He was modest, but he was sure. He said that he had made an ass ofhimself, that his broken bone was the result of his having tried to “show off” in front of “debutantes” when he dived proudly into a swimming-pool, that he had gone astray with his writing, but was ready to go back to it in full force…. I remember being impressed by the affection with which he spoke of Hemingway…. He also spoke of Hemingway with a quality that puzzled me. It was not envy of the work or the man, it was not malice. I identified it as irony…. He was not interested in me as a writer or as a woman, but he turned on his charm as deliberately as a water-tap, taking obvious pleasure in it. The irony was here, too, as though he said, “This is my little trick. It is my defiance, my challenge to criticism, to being shut out.”

Not very long before this Fitzgerald and Perkins had been taken to see an old Southern house by a member of the family.

Scott and I—Perkins remembered—both being Yankees… took a kind of interest in all this, which Scott, who was very sensitive, perceived was not considerate of our companion’s feelings. So he suddenly launched into an account of the surrender at Appomattox. “Well,” he said, “it was all a great mistake, the surrender. The facts never got out. The camera men flashed the pictures at the wrong moment, and then it couldn’t be changed to the truth. For the truth was that… Grant said, ‘General Lee, there is no pen here. May I borrow your sword to sign with?’ For Grant, of course, had no sidearms, as history records. And in the moment when Lee courteously handed him his sword for that purpose the press pictures were taken.”

“This,” Perkins adds with his usual modesty, “doesn’t sound like much when written, but Scott in all his high spirits made a fine thing of it.” All the characteristic elements are here: Fitzgerald’s comic nonsense about camera men, the joke about the strength of pens and swords, the high spirits, the desire tomake others happy. This, like the Fitzgerald Mrs. Rawlings saw, is the old unbeaten Fitzgerald.

His shoulder gradually mended through the autumn and he got himself “an ancient Packard roadster” and began to get out again. In September his mother died. She left $42,000 and he tried hard to get his share of it at once; it would not have been much: he owed his mother’s estate $5000 or $6000. “… it would be suicidal,” he wrote his sister, “to keep on writing at this nervous tensity often with no help but what can be gotten out of a bottle of gin…. There is no use reproaching me for past extravagances nor for my failure to get control of the liquor situation under these conditions of strain…. [I] have used the liquor for purposes of work or of accomplishing some duty for which I no longer have the physical or nervous energy.”

When it became clear that there would be no money from the estate for six months or so, he turned, for the first time in his life, to a wealthy friend for help. “I do not know,” he wrote, “very many rich people well, in spite of the fact that my life has been cast among rich people—certainly only two well enough to have called upon in this emergency…” In this way he got himself through the fall and in December he returned to Baltimore, partly at least because he wanted to give a tea dance for his daughter so that she could repay some of her social debts there. “Old dowager Fitzgerald,” he called himself. The dance was not a success, because Fitzgerald drank too much in an attempt to rise to the occasion. Once more he had to go into a hospital.

As soon as he was out, he returned to Asheville and again, as he had before his accident, he began the long pull back. With the money he had borrowed and the now imminent inheritance from his mother he had ready cash and could take things a little easier. With the pressure eased, his old Irish stubbornness reasserted itself and he began honestly to face his tendency toward “unnecessary rages, glooms, nervoustensity, times of coma-like inertia…” “I stopped drinking in January,” he wrote his cousin, “and have been concentrating on other mischief, such as work… Scottie must be educated & Zelda can’t starve. As for me I’d had enough of the whole wretched mess some years ago & seen thru a sober eye find it more appalling than ever.” To another friend he summed up the causes of his disaster: “A prejudiced enemy might say it was all drink, a fond mama might say it was not providing for the future in better days, a psychologist might say it was a nervous collapse—it was perhaps partly all these things…. My life looked like a hopeless mess there for awhile and the point was I didn’t want it to be better. I had completely ceased to give a good Goddamn. … So much for me and I don’t think it will ever happen again.”

But “when you once get to the point where you don’t care whether you live or die—as I did—it’s hard to come back to life,” and he did not come all the way back. Still he began to go about again. He took to eating in a place called Misseldine’s in Tryon and invented all sorts of wonderfully absurd stories about it. By Easter he was well enough to have his daughter for her vacation and very nearly to make a success of the visit. “I loved having you here (except in the early morning),” he wrote her when she was back at Miss Walker’s, “and I think we didn’t get along so badly, did we? Glad you had a gay time in Baltimore and New York and have a friend at Groton. They are very democratic there—they have to sleep in gold cubicles and wash at old platinum pumps. This toughens them up so they can pay the poor starvation wages without weakening.”

Next chapter 15

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).