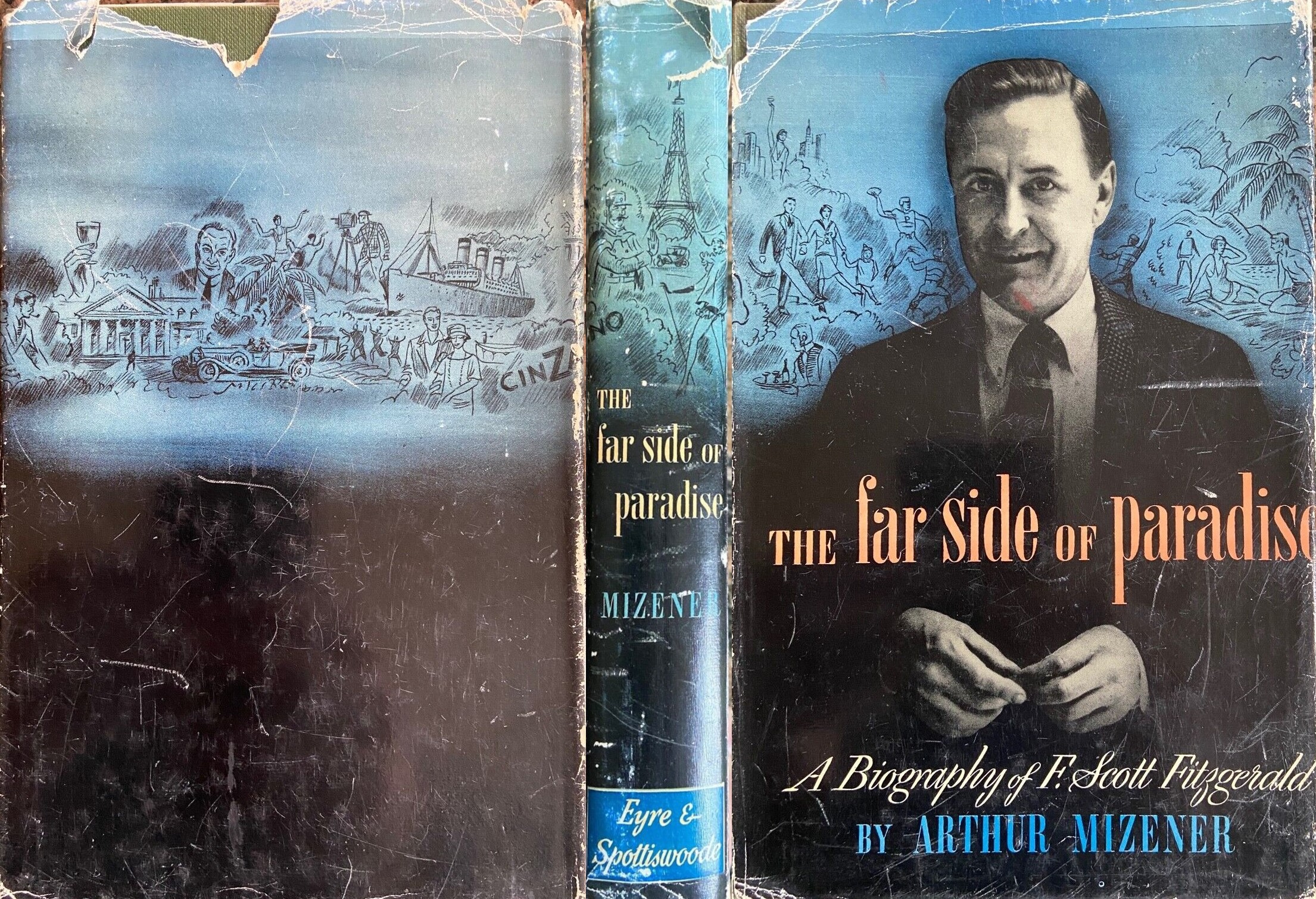

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter IX

The Great Gatsbyis usually considered Fitzgerald’s finest novel. Established opinion is represented by Lionel Trilling: “Except once, Fitzgerald did not fully realize his powers… But [his] quality was a great one and on one occasion, in The Great Gatsby, it was as finely crystallized in art as it deserved to be.” Perhaps people are so sure of this judgment, despite Tender Is the Night’s claim to consideration, because it was quickly reached when the book was published and became a commonplace during the late twenties as time passed and Fitzgerald published no new novel. The Dial called Gatsby “one of the finest of contemporary novels,” the Saturday Review said it revealed “thoroughly matured craftsmanship” and had “high occasions of felicitous, almost magic craftsmanship.” Even Mencken, though he thought that it was “in form no more than a glorified anecdote” and that Fitzgerald did not get “under the skin of its people,” was deeply impressed by “the charm and beauty of the writing.”

Fitzgerald thought he knew what bothered Mencken. “I gave no account (and had no feeling about or knowledge of) the emotional relations between Gatsby and Daisy from the time of their reunion to the catastrophe. However the lack is so astutely concealed by the retrospect of Gatsby’s past and by blankets of excellent prose that no one has noticed it. … I felt that what [Mencken] really missed was the lack of anyemotional backbone at the very height of it.” He was also capable of sharp detailed criticism of the book: “I thought that the whole episode (2 paragraphs) about their playing the Jazz History of the world at Gatsby’s first party [Chapter III] was rotten,” he wrote Perkins. “Did you? Tell me frank reaction—personal. Don’t think. We can all think! “

But whatever its limitations, The Great Gatsby was a leap forward for him. He had found a story which allowed him to exploit much more of his feeling about experience, and he had committed himself to an adequate and workable form which he never betrayed. “I want to write something new,” he told Perkins, “—something extraordinary and beautiful and simple and intricately patterned.” Where he learned how to make that pattern is not easy to say. He was never very conscious of his literary debts. What he did know was that integrity of imagination was nearly everything. As he wrote his daughter when she began to think of being a writer, “What you have felt and thought will, by itself, invent a new style, so that when people talk about style they are always a little astonished at the newness of it, because they think it is only a style that they are talking about, when what they are talking about is the attempt to express a new idea with such force that it will have the originality of the thought.” It is typical of his intuitive way of working that one of the best symbols in Gatsby, the grotesque eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg’s billboard, was an accident. Perkins had had a dust jacket designed for the book before Fitzgerald went abroad; it is a very bad picture intended to suggest—by two enormous eyes—Daisy brooding over an amusement-park version of New York. In August, 1924, as soon as Fitzgerald got back to the book, he wrote Perkins: “For Christ’s sake don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it into the book.”

The dust jacket was not, of course, the real source of that image, but it was the only source Fitzgerald consciouslyunderstood, and he was hardly more aware of his literary sources. Gilbert Seldes said that the book was written in “a series of scenes, a method which Fitzgerald derived from Henry James through Mrs. Wharton”; and Seldes had talked to Fitzgerald about the book. Moreover, Wilson had been urging James on him. He had also been reading Conrad. His use of a narrator and the constant and not always fortunate echoes of Conrad’s phrasing—e.g., “the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men”—show the extent of this influence. Yet when a correspondent of Hound &Horn ventured the guess that Thackeray had been an important influence on the book, Fitzgerald replied, “I never read a French author, except the usual prep-school classics, until I was twenty, but Thackeray I had read over and over by the time I was sixteen, so as far as I am concerned you guessed right.” Shortly after he had written THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, Fitzgerald made a list of the ten most important novels for the Chicago Tribune; in it he called Nostromo 'the greatest novel since 'Vanity Fair' (possibly excluding 'Madame Bovary')' (Clipping in Album III). In 1940 he told Perkins that 'I read [Spengler] the same summer I was writing 'The Great Gatsby,' and I don't think I ever quite recovered from him.' What Spengler meant to him he then makes clear: 'Spengler prophesied gang rule, 'young people hungry for spoil,' and more particularly 'the world as spoil' as an idea, a dominant, supersessive idea' (to Maxwell Perkins, June 6, 1940; The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Andrew Turnbull, New York, 1963 , p. 290)

His use of a narrator allowed Fitzgerald to keep clearly separated for the first time in his career the two sides of his nature, the middle-western Trimalchio and the spoiled priest who disapproved of but grudgingly admired him. Fitzgerald shuffled back and forth between their attitudes in his attempt to find a title for the book. His first suggestion, Among Ash Heaps and Millionaires, soon gave way to The Great Gatsby; but he kept experimenting with others which would suggest a more satiric attitude toward Gatsby, such as Trimalchio in West Egg. “The only other titles that seem to fit it are Trimalchio and On the Road to West Egg. I had two others Gold-Hatted Gatsby and The High-Bouncing Lover but they seemed too light,” he wrote Perkins. A month later he had returned to The Great Gatsby, but by January he was saying, “My heart tells me I should have named it Trimalchio”; and on March 25, two weeks before publication, he cabled: CRAZY ABOUT TITLE UNDER THE RED WHITE AND BLUE WHAT WOULD DELAY BE.

Perhaps the formal ordering of the Gatsby material waseasier for him because, at least in its externals, it was not so close to him as his material usually was. Wolfsheim, for instance, was based on Arnold Rothstein; Fitzgerald had met Rothstein once but knew nothing about him beyond the ordinary rumors. Gatsby himself—once again in externals—was based on a Long Island bootlegger whom Fitzgerald knew only slightly. After one visit at his place Fitzgerald told Edmund Wilson all about this man and Wilson put his description into “The Crime in the Whistler Room.” (Opposite Wilson’s description, in his own copy of This Room and This Gin and These Sandwiches, Fitzgerald wrote: “I had told Bunny my plan for Gatsby.”)

He’s a gentleman bootlegger: his name is Max Fleischman. He lives like a millionaire. Gosh, I haven’t seen so much to drink since Prohibition…. Well, Fleischman was making a damn ass of himself bragging about how much his tapestries were worth and how much his bath-room was worth and how he never wore a shirt twice—and he had a revolver studded with diamonds… And he finally got on my nerves—I was a little bit stewed—and I told him I wasn’t impressed by his ermine-lined revolver: I told him he was nothing but a bootlegger, no matter how much money he made. … I told him I never would have come into his damn house if it hadn’t been to be polite and that it was a torture to stay in a place where everything was in such terrible taste.

Again, however, these details account only for the externals of Gatsby; the vulgar and romantic young man Fitzgerald found somewhere inside himself to fill this outline of a character is what matters. About this young man he could only say, “He was perhaps created in the image of some forgotten farm type of Minnesota that I have known and forgotten, and associated at the same moment with some sense of romance … a story of mine, called “Absolution”… wasintended to be a picture of his early life, but … I cut it because I preferred to preserve the sense of mystery.” Because the form of Gatsby keeps Fitzgerald’s assertions of the romance and of the vulgarity clearly separated, he was able to make out of those unworn shirts of Max Fleischman the fine episode of Gatsby’s many shirts, to blend without confusion the elements of bad taste and idealism implied by that pile of material with “stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple green and lavender and faint orange, with monograms of Indian blue” on which Daisy suddenly bowed her head and cried.

Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald’s narrator, is, for the book’s structure, the most important character. Quite apart from his power to concentrate the story and its theme into a few crucial scenes and thus increase its impact, a great deal of the book’s color and subtlety comes from the constant play of Nick’s judgment and feelings over the events. Fitzgerald had struggled awkwardly with all sorts of devices in his earlier books to find a way to get these things in without intervening in his own person and destroying our dramatic perception of them. Nick, as one of the characters in the story, not only allows but requires him to imply feelings everywhere.

[Daisy] turned her head as there was a light dignified knocking at the front door. I went out and opened it. Gatsby, pale as death, with his hands plunged like weights in his coat pockets, was standing in a puddle of water glaring tragically into my eyes.

With his hands still in his coat pockets he stalked by me into the hall, turned sharply as if he were on a wire, and disappeared into the living-room. It wasn’t a bit funny.

Nick has come east after the war to be a real Easterner, but his moral roots are in the Middle West. He is prepared, in the book’s very first scene, to respond to the beauty and charmof Daisy, adrift like some informal goddess in that “bright, rosy-colored space” which is the Buchanans’ drawing room. But he is humorously aware of their difference: “‘You make me feel uncivilized, Daisy,’ I confessed…. ‘Can’t you talk about crops or something?’” A moment later, when Daisy has confessed her unhappiness with Tom, he has an uncomfortable glimpse of what is really involved in this difference. “The instant her voice broke off, ceasing to compel my attention, my belief, I felt the basic insincerity of what she had said. It made me uneasy, as though the whole evening had been a trick of some sort to exact a contributary emotion from me. I waited, and sure enough in a moment she looked at me with an absolute smirk on her lovely face, as if she had asserted her membership in a rather distinguished secret society to which she and Tom belonged.”

It is a secret society distinguished by more than he had supposed, for Nick is learning that the rich are different from you and me in more than their habituation to the appurtenances of wealth which give their lives such a charmed air for the outsider like Gatsby. What astonished Gatsby was the way Daisy’s beautiful house in Louisville “was as casual a thing to her as his tent out at camp was to him.” For Gatsby “there was a ripe mystery about it, a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors, and of romances that were not musty and laid away already in lavender but fresh and breathing and redolent of this year’s shining motor-cars and of dances whose flowers were scarcely withered.”

But while Nick is humorously aware of this charm, he is a Carraway and he has grown up “in the Carraway house in a city where dwellings are still called through decades by a family’s name.” When at the end of the book he unexpectedly runs into Tom in front of a jewelry store on Fifth Avenue, he thinks:

I couldn’t forgive him or like him, but I saw what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made….

I shook hands with him; it seemed silly not to, for I felt suddenly as if I were talking to a child. Then he went into the jewelry store to buy a pearl necklace—or perhaps only a pair of cuff buttons—rid of my provincial squeamishness forever.

It is characteristic of Fitzgerald’s control of his material that he can sum up all he wants to say about Tom in that last sentence with Nick’s ironic glance at the “string of pearls valued at three hundred and fifty thousand dollars” which had been the symbol of Daisy’s surrender to Tom’s world. “A pearl necklace—or perhaps only a pair of cuff buttons.” “I see you’re looking at my cuff buttons,” Meyer Wolfsheim says to Nick. “I hadn’t been looking at them, but I did now. They were composed of oddly familiar pieces of ivory. ‘Finest specimens of human molars,’ he informed me.” This kind of control is everywhere in the book. Gatsby, giving Nick his cheap-magazine version of his life, says that he “lived like a young rajah in all the capitals of Europe—Paris, Venice, Rome—collecting jewels, chiefly rubies, hunting big game, painting a little….” Nick is disgusted by this image “of a turbaned ‘character’ leaking sawdust at every pore as he pursued a tiger through the Bois de Boulogne.” But when Gatsby is showing Daisy his house and Nick sees the pictures of Dan Cody and Gatsby in yachting costume, he is on the verge of seriously “[asking] Gatsby to see the rubies.” In the same way Nick makes a little joke about Daisy’s chauffeur, Ferdie, when he brings Daisy to tea. “Does the gasoline affect his nose?” he asks. “I don’t think so,” Daisy answers innocently. “Why?” But her innocence is only assumed, for it was her own joke; she had told Nick in the book’s first scene about her butler whose nose had been permanently injured because he had to polish silver from morning till night.

So Nick, having learned just how much brutal stupidity and carelessness exist beneath the charm and even the pathos of Tom and Daisy, goes back to the West, to the country he remembers from the Christmas vacations of his boyhood, to “the thrilling returning trains of my youth, and the street lamps and the sleigh bells in the frosty dark and the shadows of holly wreaths thrown by lighted windows on the snow. I am part of that….” The East remains for him “a night scene from El Greco” in which “in the foreground four solemn men in dress suits are walking along the sidewalk with a stretcher on which lies a drunken woman in a white evening dress. Her hand, which dangles over the side, sparkles cold with jewels. Gravely the men turn in at a house—the wrong house. But no one knows the woman’s name, and no one cares.”

Thus, though Fitzgerald would be the last to have reasoned it out in such terms, The Great Gatsby becomes a kind of tragic pastoral, with the East exemplifying urban sophistication and culture and corruption, and the Middle West, “the bored, sprawling, swollen towns beyond the Ohio,” the simple virtues. This contrast is summed up in the title to which Fitzgerald came with such reluctance. In so far as Gatsby represents the simplicity of heart Fitzgerald associated with the Middle West, he is really a great man; in so far as he achieves the kind of notoriety the East accords success of his kind and imagines innocently that because his place is right across from the Buchanans’ he lives in Daisy’s world, he is great about as Barnum was. Out of Gatsby’s ignorance of his real greatness and his misunderstanding of his notoriety, Fitzgerald gets most of the book’s direct irony.

Gatsby himself is a romantic who, as his creator nearly did,has lost his girl because he had no money. On her he had focused all his “heightened sensitivity to the promises of life.” For him money is only the means for the fulfillment of “his incorruptible dream.” “I wouldn’t ask too much of her. You can’t repeat the past,” Nick says to him of Daisy. “‘Can’t repeat the past?’ he cried incredulously. ‘Why of course you can!’ “For Gatsby the habits of wealth have preserved and heightened Daisy’s charm. No one understood that better than he.

“She’s got an indiscreet voice,” I remarked. “It’s full of—“I hesitated.

“Her voice is full of money,” [Gatsby] said suddenly.

That was it. I’d never understood before. It was full of money—that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals’ song of it. … High in a white palace the king’s daughter, the golden girl….

But if a lifetime of wealth colors Daisy’s charm in a way that Gatsby’s new wealth cannot imitate, it has also given her the habit of retreating with Tom “into their money or their vast carelessness” whenever she has to face responsibility. So, as Gatsby watches anxiously outside their house after the accident in order to protect Daisy, she sits with Tom over a plate of cold fried chicken and two bottles of ale in the kitchen. “There was an unmistakable air of natural intimacy about the picture, and anybody would have said they were conspiring together.” After looking through the window at them, Nick returns to Gatsby. “He put his hands in his coat pockets and turned back eagerly to his scrutiny of the house, as though my presence marred the sacredness of the vigil. So I walked away and left him standing there in the moonlight—watching over nothing.” The next day, waiting for a telephone message from Daisy which never comes, he is shot by Wilson.

In contrast to the grace of Daisy’s world Gatsby’s fantasticmansion, his incredible car, his absurd clothes, “his elaborate formality of speech [which] just missed being absurd” all appear ludicrous. But in contrast to the corruption which underlies Daisy’s world, Gatsby’s essential incorruptibility is heroic. Because of the skilful construction of The Great Gatsby the eloquence and invention with which Fitzgerald gradually reveals this heroism are given a concentration and therefore a power he was never able to achieve again. The art of the book is nearly perfect.

Its limitation is the limitation of Fitzgerald’s own nearly complete commitment to Gatsby’s romantic attitude. “That’s the whole burden of this novel,” he wrote a friend, “—the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world so that you don’t care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory.” Fitzgerald’s irony touches only the surface of Gatsby and the book never suggests a point of view which might bring seriously into question the adequacy to experience of “a heightened sensitivity to the promises of life.” The world of Tom and Daisy, which is set over against Gatsby’s dream of a world, is superficially beautiful and appealing but indefensible: Tom’s muddled attempts to defend it, his “impassioned gibberish” about “‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard,” prove how indefensible it is.

“They’re a rotten bunch,” Nick shouts back to Gatsby as he leaves him for the last time. “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.” Then he thinks: “I’ve always been glad I said that. It was the only compliment I ever gave him, because I disapproved of him from beginning to end. First he nodded politely, and then his face broke into that radiant and understanding smile, as if we’d been in ecstatic cahoots on that fact all the time. His gorgeous pink rag of a suit made a bright spot of color….” But though the tone of this passage is perfect, even down to the irony of the colloquial “rag of a suit,” it does not seriously qualify Nick’s—and Fitzgerald’s—commitment to Gatsby, to the romantic “capacity for wonder” and its belief “in the green light, the orgiastic future,” which justifies by its innocent faith Gatsby’s corruption.

The last two pages of the book make overt Gatsby’s embodiment of the American dream as a whole by identifying his attitude with the awe of the Dutch sailors when, “for a transitory enchanted moment,” they found “something commensurate to [their] capacity for wonder” in the “fresh, green breast of the new world.” Though this commitment to the wonder and the enchantment of a dream is qualified by the dream’s unreality, by its “year by year reced[ing] before us,” the dream is still the book’s only positive good; the rest is a world of “foul dust,” like the “valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat in ridges and hills and gardens”—through which one passed every evening on his way to the night world of East and West Egg.

The first edition reads 'orgastic future,' and Fitzgerald meant it. ' 'Orgastic' is the adjective for 'orgasm,' ' he wrote Perkins (January 24, 1925; The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Andrew Turnbull, New York, 1963 , p. 175), 'and it expresses exactly the intended ecstasy. It's not a bit dirty.' Nonetheless, in his copy of the first edition in which he made a large number of pencilled corrections, he changed the adjective to 'orgiastic.' The only typographical error he corrects in this copy is the reading 'eternal' for 'external' on p. 58, and this mistake was caused by a confusing revision he made in the proofs. A few small changes were made in the second printing of the novel, but it was not until Scribner's reprint of the late fifties that an attempt was made to incorporate Fitzgerald's own corrections and revisions into the text; unfortunately they were not all correctly interpreted, and some new errors, such as dropped phrases, also crept into this edition. There is an interesting article on the text of Gatsby by Bruce Harkness, 'Bibliography and the Novelistic Fallacy,' Studies in Bibliography, 12 (1959), pp. 59-73. The best existing text of Gatsby is in The Fitzgerald Reader, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1963, though even that text is not absolutely accurate (see the Foreword, p. xiii). There remain some unsolved puzzles. Did Fitzgerald mean 'an urban distaste for the concrete' {The Fitzgerald Reader, p. 141) or 'an urbane distaste'? Did he mean 'with fire in the room' (p. 215) or 'with a fire in the room'? It seems almost certain he meant Myrtle Wilson to say, 'you'd have thought she had my appendicitus out' (p. 127), not 'you'd have thought she had my appendicitis out'; originally he wrote 'had my appendix out,' then corrected it in the galleys to 'appendicitus,' tracing over the last five letters of the word a second time to make them perfectly clear. The spelling 'appendicitis' is a copyreader's. Michaelis's name creates an inexplicable puzzle. Originally he was named Mavromichaelis, and on p. 207, when he is spelling out his name for the policeman, he begins, 'M-a-v-r-o.' But then he adds 'g'. The galleys printed this 'g' (it appears twice) as a capital and Fitzgerald carefully corrected it to lower case but did not change it. Where does it come from? There is no 'g' in either Michaelis or Mavromichaelis. A simpler puzzle, since it is an explicable kind of oversight, is Fitzgerald's writing that Gatsby 'was balancing himself on the dashboard' of his car (p. 151); this mistake for 'running board' was missed by the original copyreader, by Fitzgerald, and by all subsequent copyreaders.

2

Early in May 1925 the Fitzgeralds reached Paris from the south of France and there they rented an apartment at 14 rue de Tilsitt for the rest of the year. “It represented to some degree,” as Louis Bromfield observed, “the old aspirations and a yearning for stability, but somehow it got only halfway and was neither one thing nor the other…. The furniture was gilt Louis XVI but a suite from the Galeries Lafayette. The wall paper was the usual striped stuff in dull colors that went with that sort of flat. It was all rather like a furniture shop window and I always had the impression that the Fitzgeralds were camping out there between two worlds.” sales situation doubtful, Perkins cabled about Gatsby excellent reviews. The sales continued to be, by Fitzgerald’s standards, mediocre, though the reviews were the best he had ever had. By the time Gatsby was published, hisdebt to Scribner’s was something over $6200; by October the sales were just short of twenty thousand copies, slightly below what would have covered this debt. By February a few thousand more copies had been sold and the book was dead.

As Fitzgerald had written Bishop, “We want to come back but we want to come back with money saved and so far we haven’t saved any.” He had hoped Gatsby would make him the kind of money he wanted. This was to hope for a miracle, but Fitzgerald was an optimistic young man and events had conspired, by producing a series of brilliant successes for him, to convince him that if he did his best he would attain fame and fortune. Such expectations were a part of the pattern he had been brought up on, and if he had outgrown much of his upbringing, he had not lost his conviction that money in large quantities was the proper reward of virtue. He showed his usual mixture of naïveté and insight about this attitude. From the day he announced he would be satisfied with a sale of twenty thousand copies of This Side of Paradise he had continued to assume that a novelist should get very large returns for his work. “If,” he wrote Perkins about Gatsby, “[my next novel] will support me with no more intervals of trash I’ll go on as a novelist. If not I’m going to quit, come home, go to Hollywood and learn the movie business…. there’s no point in trying to be an artist if you can’t do your best.” This is a sensible statement—Fitzgerald knew what he could command in Hollywood—except that Fitzgerald’s idea of “support” is fantastic. His writing, even without the “trash,” had supported him more than adequately up to this time. Omitting what he got from everything that might be thought trash and including only his novels and the six best short stories he had so far written, he had averaged between $16,000 and $17,000 a year during his career as a writer (his total income from 1920 to 1924 inclusive was $113,000, a little better than $22,500 a year). This income ought to havesupported them, and Fitzgerald knew it. “I can’t reduce our scale of living,” he continued in his letter to Perkins, “and I can’t stand this financial insecurity. … I had my chance back in 1920 to start my life on a sensible scale and lost it and so I’ll have to pay the penalty…. Yours in great depression.” But why did he feel his chance had been lost at the start? A man who intends to be a serious writer in the twentieth century knows that he will be lucky to average a quarter of Fitzgerald’s income over a lifetime; and it is hard to believe anyone could be so subject to extravagance that he would have to sacrifice his whole career to it, especially when he is a man—as Fitzgerald was—powerfully driven to succeed in that career and at the same time tortured—as again Fitzgerald was—by debt.

The answer to these questions lies in Fitzgerald’s imaginative involvement with wealth and in the way its effect was reinforced by the belief in “airing the desire for unadulterated gaiety” which he and Zelda shared. It was difficult enough that Fitzgerald’s imagination drove him to try to live like a man of inherited wealth and that their extravagance and inefficiency always made that life cost more than it needed to. It was worse that, until tragedy struck them, they sought innocently and sincerely for that “orgiastic future” that haunted Gatsby. Fitzgerald’s imagination saw the meaning of their experience. No one will ever improve on Gatsby’s attempt to imitate the life of inherited wealth or his devotion to the “orgiastic future” as a commentary on Fitzgerald’s life. He also saw their inefficiency as the newly rich and made a joke of it in “How to Live on $36,000 a Year.” But his imagination could realize and evaluate this attitude because he was committed to it in practice. His financial dilemma was more than the penalty he paid for having failed to start his life on a sensible scale; it was what he paid for the theme of his finest work.

Fitzgerald later described this summer of 1925 in Paris asone of “1000 parties and no work”; he was worried about his drinking. It was easy to make a joke of it, as Hemingway, of whom they were beginning to see a great deal, did in The Torrents of Spring: “It was at this point in the story, reader, that Mr. F. Scott Fitzgerald came to our home one afternoon, and after remaining for quite a while suddenly sat down in the fireplace and would not (or was it could not, reader?) get up and let the fire burn something else so as to keep the room warm.” But he was beginning to be drunk for periods of a week or ten days and to sober up in places like Brussels without any notion of how he had got there or where he had been.

Perhaps, like most of us, Fitzgerald had always given himself the benefit of the doubt about his behavior when he was drunk, but about this time he began describing much that he did as more orderly and rational than it was. In A Moveable Feast there is a scene that, despite its exaggerated stylization, shows what was happening to him. One night at the Dingo, he had gone through the startling transformation that alcohol now and then caused in him all his life.

As he sat there at the bar holding the glass of champagne the skin seemed to tighten over his face until all the puffiness was gone and then it drew tighter until the face was like a death’s head. The eyes sank and began to look dead and the lips were drawn tight and the color left the face so that it was the color of used candle wax.

A few days later Hemingway said to him he was sorry the stuff had hit him so hard.

“What do you mean you are sorry? What stuff hit me what way? What are you talking about, Ernest?”

“I meant the other night at the Dingo.”

“There was nothing wrong with me at the Dingo. I simply got tired of those absolutely bloody British you were with and went home.”…

“Yes,” I said. “Of course.”

“That girl with the phoney title who was so rude and that silly drunk with her. They said they were friends of yours.”

“They are. And she is very rude sometimes.”

“You see. There’s no use to make mysteries simply because one has drunk a few glasses of wine. Why did you want to make the mysteries? It isn’t the sort of thing I thought you would do.”

More and more often during these years alcohol affected Fitzgerald in this way; as Hemingway remarked on another occasion in his brutally precise way, “Fitzgerald was soft. He dissolved at the least touch of alcohol.” For his account of his conduct at the Dingo, Fitzgerald probably had some complicated motive derived from his conception of the personal relations between himself and Hemingway, for in his novelist’s way he always had a half-shrewd, half-fantastic theory of such relations in terms of which he maneuvered with the care of a general responsible for whole armies. Not, as Callaghan shows, that Fitzgerald was systematically devious in personal relations in the way Hemingway was, for he was much less self-protective. But they were both complex men.

Still, making every allowance for motives of this kind, Fitzgerald’s conception of that night at the Dingo is dangerously remote from what he actually did as Hemingway describes it, and his conceptions of other situations, where there were no complicated personal relations, were often equally remote from the facts. Perhaps he improved his accounts of these more trivial occasions for the benefit of his listeners without himself losing track of the facts—all his life he had tried to entertain people by making good stories out of his experience—but it is difficult not to suspect that at this time he was beginning to lose track of the second of the two rules he says in his Notebooks he made for himself in order that he might be “both an intellectual and a man of honor simultaneously,” namely, “that I do not tell… lies that will be of value to myself, and secondly, I do not lie to myself. (A little episode in That Summer in Paris illustrates the course Fitzgerald's ceaseless self-analysis was taking at this time. One night as he and Callaghan were walking toward the Deux Magots, when Fitzgerald was exhausted and a little drunk, 'he linked his arm in mine. For about fifty paces he held on to my arm affectionately. I didn't notice him suddenly withdrawing his arm.' Sometime later he said suddenly to Callaghan, 'Remember the night I was in bad shape? I took your arm. Well, I dropped it. It was like holding on to a cold fish. You thought I was a fairy, didn't you?' This particular fantasy is probably traceable to the accusations Zelda, in her disturbed state, was making at this time, accusations that appear in their turn to be developments of the complaints of his sexual inadequacy that Zelda made in earlier quarrels and that led Fitzgerald to make the anxious inquiries that elicited the grotesque advice Hemingway reports in A Moveable Feast (see That Summer in Paris, pp. 193 and 207 and A Moveable Feast, pp. 189-191). Hemingway took this problem very seriously; he brought it up again years later at a disastrous dinner with Fitzgerald and Wilson in New York, in 1933.)

For example, in December of this year he told Perkins that “I called on Chatto & Windus in London last month and had a nice talk with Swinnerton, their reader.” Swinnerton’s version of that “nice talk” is different.

I went from my office to the waiting-room, where a young man sat, with his hat on, at a small table. He did not rise or remove his hat, and he did not answer my greeting, so I took another chair, expressing regret that no partner was available, and asking if there was anything I could do. Assuming, I suppose, that I was some base hirling, he continued brusque to the point of truculence; but we spoke of the purpose of his visit, and after a few moments he silently removed his hat. Two minutes later, looking rather puzzled, he rose. I did the same. I spoke warmly of The Great Gatsby ; and his manner softened. He became an agreeable boy, quite ingenuous and inoffensive, and finally asked my name. I told him. If I had said ‘The Devil’ he could not have been more horrified. Snatching up his hat in consternation, he cried: ‘Oh, my God! Nocturne’s one of my favorite books!’ and dashed out of the premises.33

But Fitzgerald continued to suspect Chatto & Windus of snubbing him; 'they answered a letter of mine on the publication of [The Great Gatsby] with the signature (Chatto & Windus, per Q), undoubtedly an English method of showing real interest in one's work'.

A very similar Fitzgerald appears in Hemingway’s story about going to Lyons with Fitzgerald that spring of 1925 to pick up the car they had left there on their way north. To be sure, Hemingway represents himself in this story as the skilful man of the world handling the impossible drunk with a perfection of ingenuity and patience it is not quite possible to believe in. Nonetheless, Fitzgerald’s insistence that he was suffering from “congestion of the lungs” is characteristic of him in this state, and it must have been particularly maddening to Hemingway with his conviction that the ability to hold one’s liquor is an important manifestation of manliness and his feeling that people like Fitzgerald who could not were “soft.” “You could not,” he said, “be angry with Scott any more than you could be angry with someone who was crazy, “a conclusion which damns Fitzgerald very thoroughly with faint affection. In any event, it is difficult to know how much Fitzgerald was putting a good face on things and how much he was deceiving himself—his ordinary self; the writer in him understood completely even his most drunken moments and used them in stories—when he wrote Gertrude Stein a little later that “Hemingway and I went to Lyon shortly after to get my car and had a slick drive through Burgundy. He’s a peach of a fellow and absolutely first-rate.”

But though it is not possible to determine how much Fitzgerald understood what was happening to him, it is clear he felt himself to be living in a nightmare. Something of what he felt during these years he put into “Babylon Revisited,” and in The World’s Fair he described one of its evenings in detail.

… then six of us, oh, the best the noblest relicts of the evening… were riding on top of thousands of carrots in a market wagon, the carrots smelling fragrant and sweet with earth in their beards—riding through the darkness to the Ritz Hotel and in and through the lobby—no, that couldn’t have happened but we were in the lobby and the bought concierge had gone [f]or a waiter for breakfast and champagne. We were making a waiter trap—what was it, something about a waiter trap, made of—I have forgotten, but I remember with almost the vividness and violence of his native plains, Mr. George T. Horseprotection.

He was a large brown splendidly-dressed oil-Indian—with many faults; he had been out all night and was coming home to bed but presently he was sitting with us, wide awake and trying to pay for the champagne. I was a little ashamed of him before Major Hengest but to my surprise Major Hengest was very impressed so I began, weakly, to like him too. It was quarter of five and Napoleon looked a little formidable on top of his column but we went on to the Grand Duc with him.

The Grand Due had just begun its slow rattling gasp forlife in the inertness of the weakest hour. Discernible near us through the yellow smoke of dawn were Josephine Baker, the Grand Duc Boris, Eskimo, Pepy, a manufacturer of dolls voices from Newark, Albert McKiscoe happily unable to walk and the King of Sweden. In the corner a huge American negro, with his arms around a lovely French tart, roared a song to her in a rich beautiful voice and suddenly Melarky’s Tennessee instincts remembered and were aroused. … he began looking at everyone disagreeably and truculently. Dinah glanced at him and then suddenly got up to go.

She was a minute too late. As we were going another colored man was coming in—he had just finished playing in some night club orchestra for he carried a horn case, and was coming to meet his friends—the case swung against Francis’ knee.

“God damn it, get out of my way! “said Francis savagely, “Or I’ll push your black face in.”

“You’re not behaving like a gentleman should behave,” said the colored man indignantly, “I cern’ly intended—“

“Put down that case! “

Then, before we could intervene it had happened—Francis hit him a smashing blow in the jaw and he crashed up against the door and down into the café—his legs disappearing slowly down [the] steps.

… At that moment Mr. John B. Horseprotection came rushing out and in a moment we were in a cab with him. Major Hengest with great presence of mind had gotten the two women into another taxi and called to me that he was taking them home.

“Now then,” said John T. Horseprotection in character, “Ah’ll take you gentlemen to the best place on the reservation.”

Francis sat there with a haunted face, “God, what a son-of-a-bitch I am. He was a nice-looking fellow.” Tears began to run out of his eyes, “Sort of dignified—just finished his work. Was Dinah gone?”

“Nobody saw. We’re all sons-of-bitches sometimes,” I assured him generously….

“Here we are,” interrupted Mr. Horseprotection. “Now you see something—something really funny. They have to know you, but I guess they know me.”

And then suddenly we were in a world of fairies—I never saw so many or such a variety together. There were tall gangling ones and little pert ones with round thin shoulders, and great broad ones with the faces of Nero and Oscar Wilde, and fat ones with sly smiles that twisted into horrible leers, and nervous ones who hitched and jerked opening their eyes very wide. There were handsome, passive dumb ones who turned their profiles this way and that, noble-faced ones with the countenances of senators that dissolved suddenly into girlish fatuity; pimply studgy ones with the most delicate gestures of all; raw ones with red lips and frail curly bodies… self-conscious ones who looked with eager politeness toward every noise; English ones with great racial self-control, Balkan ones—a small cooing Japanese.

The others must have been looking around simultaneously, for we all said “Let’s get out” together. After that we rode in the Bois I think. Then Francis and Abe and I, the last survivors went in to drink coffee in the Ritz Bar.

“But don’t get up close,” as Father Schwartz, the mad priest of “Absolution” who also longed for the world’s fair, says, “because if you do you’ll only feel the heat and the sweat and the life.”

But the time was not all spent like that. There was a scheme according to which Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Dean Gauss met once a week for lunch and discussed some serious topic, setting the topic for the next meeting at the end of each session so that they could prepare themselves. Fitzgerald also had the satisfaction of Gatsby’s critical reception. In addition to the handsome reviews, he got many personal lettersof great enthusiasm. “It is just four o’clock in the morning,” Deems Taylor wrote him, “and I’ve got to be up at seven, and I’ve just finished ‘The Great Gatsby’, and it can’t possibly be as good as I think it is.” Similar letters came from Woollcott and Nathan, from Cabell and Seldes, from Van Wyck Brooks and Paul Rosenfeld. Even better were the letters from Willa Cather and Mrs. Wharton and T. S. Eliot; these overwhelmed the Fitzgerald who stood in awe of distinguished writers: he got the Gausses out of bed at one in the morning to come over and celebrate Willa Cather’s letter. The letter from Mrs. Wharton, with its modesty and its informed comments on the book, meant more to him than all the others, for Mrs. Wharton was a remote and awful figure to the young rebels of Paris.

When it turned out that Mrs. Wharton wanted them to come to the Pavillon Colombe for tea, Fitzgerald was flattered and ready to throw himself once more at the feet of the author of Ethan Frome. When the day arrived, Zelda said she was damned if she would go forty or fifty miles from Paris just to let an exceedingly proper and curious old lady stare at her and Scott and make them feel provincial. Fitzgerald therefore went alone, full of trepidation and secretly, perhaps, suspecting Zelda might be right. All the way out he kept stopping to fortify himself, and bit by bit became more determined not to be put down. No doubt all his feelings of inferiority as a Middle-Westerner, as a product of the lower-middle class, and as a member of the younger generation were aroused. He was scarcely settled for tea with Mrs. Wharton and the few guests she had gathered to meet him than he set out to show them all he was not cowed. The conversation went something like this.

“Mrs. Wharton,” Fitzgerald demanded, “do you know what’s the matter with you?”

“No, Mr. Fitzgerald, I’ve often wondered about that. What is it?”

“You don’t know anything about life,” Fitzgerald roared, and then—determined to shock and impress them—“Why, when my wife and I first came to Paris, we took a room in a bordello! And we lived there for two weeks! “

After a moment he realized that, instead of being horrified, Mrs. Wharton and her guests were looking at him with sincere and quite unfeigned interest. The bombshell had fizzled; he had lied outrageously, shocked himself, and succeeded only in bringing his audience to an alert and friendly attention. After a moment’s pause Mrs. Wharton, seeming to realize from his expression how baffled Fitzgerald was, tried to help him.

“But Mr. Fitzgerald,” she said, “you haven’t told us what they did in the bordello.”

At this Fitzgerald fled, making his way back to Paris, where he was to meet Zelda, as best he could. At first when Zelda asked him how it had gone he assured her that it had been a great success, they had liked him, he had bowled them over. But gradually the truth came out, until—after several drinks—Fitzgerald put his head on his arms and began to pound the table with his fists.

“They beat me,” he said. “They beat me! They beat me! They beat me!”

I owe this anecdote to Mr. Robert Chapman, who made a note of it immediately after hearing it from Richard Knight. A slightly different version of how Fitzgerald told the bordello story and what Mrs. Wharton said in reply appears in Andrew Turnbull's Scott Fitzgerald, p. 154. Mr. Turnbull's version comes from Theodore Chanler, who was at the Pavillon Colombe that day, and it may be the more accurate. Mr. Turnbull makes no reference at all to Fitzgerald's subsequent conversation with Zelda. It seems probable that Mr. Knight, who was a closer friend of Zelda than of Fitzgerald, got this detail as well as his version of the conversation at the Pavillon Colombe from Zelda. Probably no recollection of an episode like this will be letter perfect, certainly not at the distance of time at which Mr. Knight and Mr. Chanler were reporting it.

In August they went to Antibes for the month. “There was no one at Antibes this summer,” Fitzgerald wrote Bishop, “except me, Zelda, the Valentinos, the Murphy’s, Mistinguet, Rex Ingram, Dos Passos, Alice Terry, the MacLeishes, Charles Bracket, Maude Kahn, Esther Murphy, Marguerite Namara, E. Phillips Openheim, Mannes the violinist, Floyd Dell, Max and Chrystal Eastman, ex-Premier Orlando, Etienne de Beaumont—just a real place to rough it and escape from all the world. But we had a great time.” This year was the beginning of that brief period when a group of Americans were to make on the summer Riviera a brilliant social life. “The gay elements of society,” said Fitzgerald, “had divided into twomain streams, one flowing toward Palm Beach and Deauville, and the other, much smaller, toward the summer Riviera. One could get away with more on the summer Riviera, and whatever happened seemed to have something to do with art. From 1926 to 1929, the great years of the Cap d’Antibes, this corner of France was dominated by a group quite distinct from that American society which is dominated by Europeans.” The Cap d’Antibes was remote enough to seem safe from the tourists; it was an uncomfortable overnight trip from Paris; it was also primitive enough to seem very French: the movie house operated only once a week; the telephone service was shut down for two hours at noon and completely after seven at night. This happy situation did not of course last; already in 1925, as Fitzgerald’s letter to Bishop shows, things were getting out of hand, and by 1927 the half-mile of glorious beach was jammed with Americans, an apartment house was going up, and there were two American bars doing a flourishing business. By 1929 no one swam off Eden Roc any more, except for a hangover dip at noon; people spent their time, as Fitzgerald said, in the bar discussing each other.

But for a few years after the Gerald Murphys had made it the style of a special few, it was a gay, casual, informal place. The men wore French workmen’s shirts, striped bathing trunks, and jockey caps; they lived an easy, relaxed life between beach and villa and the blue shuttered Hôtel du Cap d’Antibes. The whole feeling of the place is in the opening chapters of Tender Is the Night, how remarkably you see when you compare Fitzgerald’s account of it with some other description such as that in Charles Brackett’s American Colony. Gerald and Sara Murphy, with their charm, their social skill, and their wealth, were the heart of the original group. Fitzgerald drew on Gerald Murphy for these characteristics in Dick Diver. Murphy was always inventing amusing games for everyone, including the children: he once arranged an elaborate mock wedding between himself and Fitzgerald’sdaughter, which was carried out with perfect gravity. Mrs. Murphy shared her husband’s social gifts; “Picasso always said of her (even if she’d prepared a basket lunch for the beach) ’sara est très festin.’ “This gift baffled and fascinated Fitzgerald; as one of their friends remarked, “he thought it was something you did with money.” Imaginatively the Fitzgeralds were more than equal to the demands of a society like this. Once, for instance, Fitzgerald got up a children’s-party game about the Crusades involving complicated maneuvers with a famous set of lead soldiers. Nearly a decade later Robert Benchley wrote him, after reading Tender Is the Night: “Anyone who gets down on his stomach and crawls all afternoon around a yard playing tin-soldiers with a lot of kids, shouldn’t be made unhappy. I cry a little every time I think of you that afternoon in Antibes.”

But, like all skilful hosts, the Murphys ruled firmly: people were expected to fall in with their schemes. Their parties were carefully planned and as beautifully managed as the Divers’ party. Occasionally people failed to accept the place assigned them. Fitzgerald is said to have got drunk once when he was omitted from a Murphy party, and to have stood outside the garden where the guests were having cocktails and thrown the contents of a garbage can over the wall into their midst. But with the Fitzgeralds such gestures were something more than social rebellion. They had reached a stage which was difficult for themselves as well as others, and, like Dick Diver, Fitzgerald began to find himself excluded not only from parties but from hotels and other public places. They still believed that life ought to provide them something wonderful and exciting to do. “We grew up,” Zelda said ironically later, “founding our dreams on the infinite promise of American advertising. I still believe that one can learn to play the piano by mail and that mud will give you a perfect complexion.” To do what you wanted to was a matter of your honor, of your “sincerity.” The Fitzgeralds had beencommitted to this conception of sincerity from the start. But as time went on and they satisfied the accumulated and organized desires of their early years, doing what they wanted to became doing whatever momentary impulse suggested. Less and less did they find any long-term desires to which they wanted to sacrifice their momentary inclinations; more and more they lived at the edge of consciousness, where all the obscure and confused impulses of their natures hovered. They were at the mercy of these impulses because they were still striving to reach a kind of activity which would seem unusual and exciting.

Impulse led them to act extravagantly and incalculably. One night at the Casino at Juan-les-Pins, very late in the evening, Zelda suddenly rose from the table and, holding her skirt high, danced around the empty ball room, seriously, with great dignity, appallingly alone with her impulse to express herself. On another occasion, in Nice, as they were going down the steps into a night club, they encountered an old woman “with a tray of all sorts of little paper cornucopias of nuts and candies, rather prettily laid out.” When some of the party stopped to admire it, Fitzgerald “gave it a sort of gay nineties kick and sent everything flying.” It was, as one of his friends remarked, “an ugly little scene,” very like the scene between Francis Melarky and the Negro, and like Francis, Fitzgerald was full of remorse the minute his friends remonstrated with him—“You know,” said one of them long afterwards about the episode, “how sore you get with a small child you are fond of who acts up?”

Under the pressure of such disorganized desires the Fitzgeralds became more and more unpredictable. One evening, with the Murphys, they found themselves at a table next to Isadora Duncan at a small inn in the mountains. It quickly became apparent that Fitzgerald was the man she had, according to her custom, selected to spend that night with. He went over to her table and sat at her feet while she ran her handsthrough his hair and called him “my centurion.” Presently she arose to go, telling Fitzgerald where she was staying in a loud, clear voice. At this Zelda, who out of some pride or principle never remonstrated with Fitzgerald and had been ignoring the whole episode, stood up, leapt across the table, and plunged down a long flight of stone steps. When the Murphys reached her she was cut and bleeding but not seriously hurt. She offered no explanation. By now both Fitzgeralds felt they must go on to something exciting. Scott proposed that they put all the chickens they could find at the inn, some sixteen, on the spit in the great fireplace and cook them. But the Murphys insisted on going home. Within a short time the Fitzgeralds followed them, but at a point on the road where it crossed a trolley line, they turned up the track onto a trestle instead of following the road. Their car bumped over the open ties a few yards and stalled. They settled back in their seats and fell asleep, though they had been told that the trolley came around a blind curve and onto this trestle at high speed so that even the crossing was very dangerous. They were found the next morning by a peasant, up early to take his vegetables to market, and carried to safety by him less than twenty minutes before the morning trolley crashed into their car and smashed it to pieces.

Next chapter 10

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).