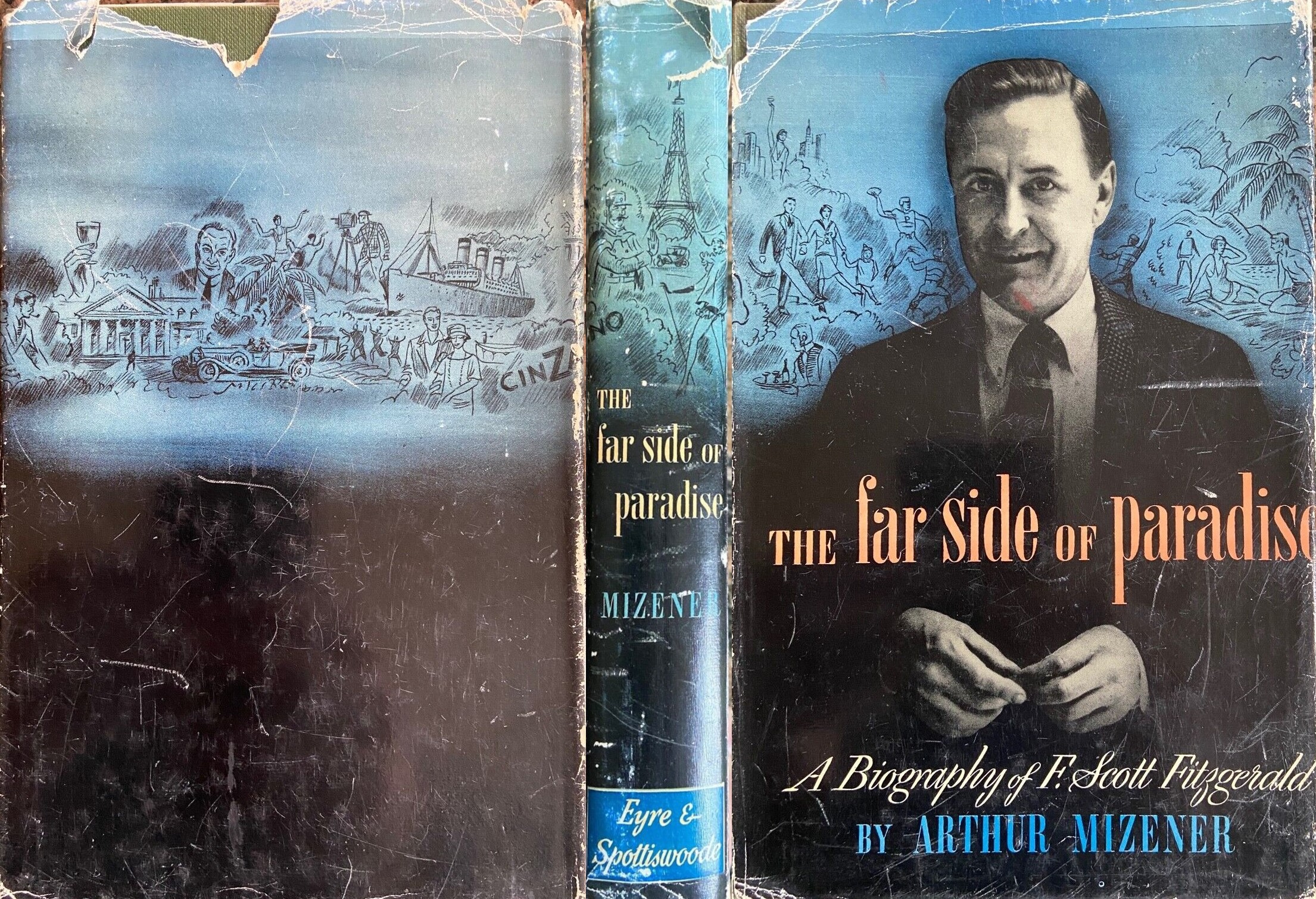

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter X

While this “great time” at Antibes was going on Fitzgerald conceived the plan for The World’s Fair, a novel on which he was to work for three years before giving up the plot and most of what he had written and starting afresh. The World’s Fair—it was also called at one time or another The Boy Who Killed His Mother and Our Type—is the story of a talented boy, Francis Melarky, who makes a success in Hollywood as a technician and then is brought to the Riviera by his mother for a vacation. His father is serving a long prison term, apparently for some crime of violence; there is a suggestion that Francis has inherited a murderous temper. Francis’ mother is a commonplace woman distinguished only by her unscrupulous determination to retain possession of Francis; there is bad feeling between them from the beginning. Fitzgerald intended to have Francis kill his mother—“Will you ask somebody,” he wrote Perkins, “what is done if one American murders another in France. … In a certain sense my plot is not unlike Dreiser’s in the American Tragedy.” The murder had been central to the plot from the moment of the novel’s conception at Antibes: “Our Type,” he had written Perkins when he first got the idea for it, “is about several things, one of which is an intellectual murder on the Leopold-Loeb idea. Incidentally it is about Zelda and me and the hysteria of last May and June in Paris.” As Fitzgerald workedon the novel during the next three years and studied the Murphys and Antibes, he began to shift the background from Paris to the Riviera; this change can be seen taking place between the versions of a given passage (for some parts of the story there are three versions). Altogether Fitzgerald completed four long chapters—about twenty thousand words—before he gave up this story of matricide in 1929.

The book originally began with a chapter describing Francis’ getting in a fight with the Italian police and being beaten up, as Fitzgerald had been, but this chapter was presently made the seventh and the second chapter made the beginning. This chapter describes the arrival of Francis and his mother on the Riviera and—except for the relation of Francis and his mother and a fine scene with Mary and Abe Grant (North)—is like the opening chapter of Tender Is the Night. It is followed by the Pipers’ (Divers’) dinner party and the duel and, finally, a long chapter in which Francis accompanies the Pipers to Paris to see Abe Grant off to America. This is the chapter which uses “the hysteria of last May and June in Paris,” most of which was eliminated in Tender Is the Night to make way for the love affair between Dick and Rosemary.

But though Fitzgerald sent Perkins an optimistic report of progress in September and was still trying to put a good face on things a month later (“… progresses slowly and carefully with much destroying and revision”), he was getting little work done. There were many parties, in Paris with the Murphys and the Hemingways and the MacLeishes, and in London. “[We] went,” wrote Fitzgerald, with his characteristic ambivalence about such things, “on some very high tone parties with Mountbattens and all that sort of thing. Very impressed, but not very, as I furnished most of the amusement myself.” It was an unhappy winter. They were tired of parties without seeming able to stop going to them, and things had gone stale. “… if somebody would come along,” says the heroine of Save Me the Waltz of this time, “to remind us about how we felt about things when we felt the way they remind us of, maybe it would refresh us.” They quarreled with the Murphys and Fitzgerald had a nasty argument with Robert McAlmon, one of the expatriates. Their apartment in the rue de Tilsitt, like nearly every place they ever lived, was uncomfortable; it “smelled of a church chancery because it was impossible to ventilate” and turned out to be “a perfect breeding place for the germs of bitterness they brought with them from the Riviera.”; When Zelda became ill in January they departed with relief for Salies de Béarn in the Pyrenees.

During that fall Owen Davis had made a dramatic version of The Great Gatsby and on February 2, 1926, it opened at the Ambassador Theatre in New York, with James Rennie as Gatsby and Florence Eldridge as Daisy. Davis’ version begins with a prologue which deals with the meeting of Daisy and Gatsby in Louisville, goes directly to Nick Carraway’s cottage for their first post-war meeting, and runs the plot out with two acts in Gatsby’s library. Wilson becomes Tom Buchanan’s chauffeur and so moves into the play, as Alexander Woollcott put it, “bag and, as you might say, baggage.” Daisy begins the final sequence of events by offering to become Gatsby’s mistress, and her offer is rejected. Thus Davis answers the question which Fitzgerald could not.

Rennie was well cast as Gatsby, and there was little doubt after the first few nights that Brady had a success. Percy Hammond summed up the general impression when he wrote: “Mr. Davis’s deft shifting of the book’s essential episodes is a marvel of rearrangement and dovetailing…. The speech of the characters is retained in much of its clear-cut veracity, and the ‘atmosphere’ of Long Island’s more rakish sectors is pretty well preserved…. ‘The Great Gatsby’ in the theater is at least half as satisfactory an entertainment as it is in the book.” One newspaper noticed that coincident with the opening ofthe play three speakeasies also opened in West 49th Street. The play ran into the summer and had a considerable career on the road.

“… as it was something of a succès d’estime” Fitzgerald wrote Harold Ober of the play, “and put in my pocket seventeen or eighteen thousand … I should be, and am, well contented.” The play’s success also made possible the sale of Gatsby to the movies, from which Fitzgerald received $15,000 or $20,000 more. These windfalls were welcome, for during 1925 and 1926 his total production was seven short stories and a couple of articles (1925: 'Not in the Guidebooks,' 'A Penny Spent,' 'The Rich Boy,' 'Presumption,' 'The Adolescent Marriage,' 'My Old New England Farm House on the Erie.' 1926: 'Your Way and Mine,' 'The Dance,' 'How to Waste Material.' ). The three main parts in the movie were taken by Warner Baxter, Lois Wilson, and Neil Hamilton; a new actor named William Powell was thought to be very effective as Wilson, the garage man. The picture ended with a subtitle to the effect that some people—meaning Gatsby—live and die for others, followed by a shot of Tom and Daisy and the wee one carefully posed on the porch of their happy home. It is probably best summed up by a review which remarks that it was “a racy, raw, and sentimental concoction which Mr. Fitzgerald will not relish but most of the movie fans will.”

According to Scribner’s regular custom, The Great Gatsby was followed in February, 1926, by a volume of short stories. Fitzgerald had not made a collection of stories since Tales of the Jazz Age in the fall of 1922, and he was confident he could put together a book with “no junk in it.” He certainly included in All the Sad Young Men nothing he knew to be junk and it is a far better book than his previous collections. The enforced production of short stories after the failure of The Vegetable in the winter of 1924 gave him an accumulation of twenty-one stories to choose from, and despite what he said of the 1924 stories at the time they were written, they were not all bad. Six of the nine stories he chose for All the Sad Young Men came from this group, though two of the remaining three—“Winter Dreams” (written inSeptember, 1922) and “The Rich Boy” (written between April and August, 1925)—are the best stories in the volume. These two stories also show the difference between Fitzgerald’s early short stories and those of the middle period of his career.

Into “Winter Dreams” he got all the acute sense of the destructiveness of time which was his strongest feeling as a young writer—the sadness of Judy Jones’ loss of beauty, the greater sadness of Dexter Green’s discovery that he has lost the ability to feel this loss. When Dexter Green, having given up Judy Jones, discovers that “so soon, with so little done, so much of ecstasy had gone from him,” he welcomes the chance to return to her and to be “unconsciously dictated to by his winter dreams again.” It was, though he did not quite understand it, a great relief to him to discover he was still capable of ecstasy. When, after seven years of not seeing her, he is told that she has faded, he feels sad that her magic is gone, but he feels overwhelming grief that he cannot care very much that it has. This loss of the ability to feel deeply is the story’s theme, and Fitzgerald realizes it in a narrative which is full of good, honest things. But the theme has certain limitations. These limitations are clear in Dexter Green’s final judgment, where the discrepancy between his overwhelming grief and its occasion creates a faint air of false rhetoric: “‘Long ago,’ he said, ‘long ago, there was something in me, but now that thing is gone. Now that thing is gone, that thing is gone. I cannot cry. I cannot care. That thing will come back no more.’“ This slightly disturbing effect reaches out into the story’s structure too. It makes something Fitzgerald knew was important to his sense of experience—Dexter’s business career, his place in the world—appear irrelevant and thus gives to what is really a carefully constructed story an air of looseness. At one point Fitzgerald himself says half apologetically that “things creep into [this story] which have nothing to do with those dreams [Dexter] had when he was young.” Theydo have something to do with the dreams Fitzgerald wanted to tell, but not with those he clearly understood he was telling.

“The Rich Boy” is a finer story than “Winter Dreams” because Fitzgerald understood his own intention better when he wrote it. Now he was so aware of how much Anson Hunter’s place in the world mattered that he made the story primarily one of how Anson’s queer, rich-boy’s pride deprived him of what he wanted most, a home and an ordered life. Hating not to dominate, Anson cannot love those he does dominate, cannot commit himself to the human muddle as he must if he is to have the life he wants. All the cross currents of his nature are displayed in the understated climactic scene when Anson spends a night with Paula and her husband just before Paula’s baby is born.

She rested her head against [her husband’s] coat.

“He’s sweet, isn’t he, Anson?” she demanded.

“Absolutely,” said Anson, laughing.

She raised her face to her husband.

“Well, I’m ready,” she said. She turned to Anson: “Do you want to see our family gymnastic stunt? “

“Yes,” he said in an interested voice.

“All right. Here we go!”

Hagerty picked her up easily in his arms.

“This is called the family acrobatic stunt,” said Paula. “He carries me up-stairs. Isn’t it sweet of him?”

“Yes,” said Anson.

Hagerty bent his head slightly until his face touched Paula’s.

“And I love him,” she said. “I’ve just been telling you, haven’t I, Anson? “

“Yes,” he said.

“He’s the dearest thing that ever lived in this world; aren’t you, darling?… Well, good night. Here we go. Isn’t he strong?”

“Yes,” Anson said.

“You’ll find a pair of Pete’s pajamas laid out for you. Sweet dreams—see you at breakfast.”

“Yes,” Anson said.

The very rich are different from you and me. So precise is Fitzgerald’s awareness of how Anson Hunter differs that he gets all his climaxes with quiet moments like this one and never has to resort to rhetoric. Because every paragraph implies much more than it says, the story appears much more tightly constructed than “Winter Dreams,” though the two stories are planned in much the same way. “Anson’s first sense of his superiority came to him when he realized the half-grudging American deference that was paid to him in the Connecticut village [where the Hunters had their summer home]….” “He was convivial, bawdy, robustly avid for pleasure, and we were all surprised when he fell in love with a conservative and rather proper girl.” “There were so many friends in Anson’s life—scarcely one for whom he had not done some unusual kindness and scarcely one whom he did not occasionally embarrass by his bursts of rough conversation or his habit of getting drunk whenever and however he liked.”

There are other good stories in All the Sad Young Men. There is “Absolution,” which contrasts a romantic young man, who has a bad conscience and dreams of himself as a worldly hero named Blatchford Sarnemington, with a spoiled priest, who is filled with piety and a maddening dream of a life like an eternal amusement park. There is “The Adjuster,” where only the handling of Doctor Moon spoils a fine account of suffering and maturity. There is “‘The Sensible Thing’ “with its moving description of Fitzgerald’s own wooing. It was a good book and it fully deserves its favorable critical reception and its sale of fourteen thousand copies.

During this winter of 1924-25 Fitzgerald devoted himselfto getting Hemingway recognized. At least a year earlier he had recommended Hemingway to Perkins’ attention; now he started to work on all his friends. Glenway Wescott has recalled how Fitzgerald drew him aside at Antibes and urged him to do something to help Hemingway’s career.

He thought I would agree that The Apple of the Eye and The Great Gatsby were rather inflated market values just then. What could I do to help launch Hemingway? Why didn’t I write a laudatory essay on him? With this questioning, Fitzgerald now and then impatiently grasped and shook my elbow. There was something more than ordinary art-admiration about it, but on the other hand it was no mere matter of affection for Hemingway. … I was touched and flattered by Fitzgerald’s taking so much for granted. It simply had not occurred to him that unfriendliness or pettiness on my part might inhibit my enthusiasm about the art of a new colleague and rival.

It did not inhibit Fitzgerald, who hastened to write his own laudatory essay, “How to Waste Material,” for The Bookman.

Hemingway had just finished The Torrents of Spring and had completed the first draft of The Sun Also Rises (the final draft was ready in April). His publishers, Boni & Liveright, were embarrassed by The Torrents of Spring: Sherwood Anderson was one of their most valuable authors, and The Torrents of Spring is a parody of Anderson. But they did not want to lose The Sun Also Rises, and Hemingway would be legally free to take it elsewhere if they rejected The Torrents of Spring. It is hardly surprising that Boni & Liveright were convinced Hemingway deliberately wrote The Torrents of Spring as part of a plot, devised by him and Fitzgerald, to free him from them. In the end, however, they decided to reject Hemingway’s parody. Fitzgerald had certainly hoped the matter would work out this way, but there is no reason to supposeHemingway wrote the book for this purpose. “[Ernest’s] book,” Fitzgerald wrote Perkins, “is almost a vicious parody-on Anderson. You see I agree with Ernest that Anderson’s last two books have let everybody down who believed in him—I think they’re cheap, faked, obscurantic and awful.” This was Hemingway’s motive. “I have known all along,” he wrote Fitzgerald, “that they could not and would not be able to publish it as it makes a bum out of their present ace and best seller Anderson. Now in 10th printing. I did not, however, have that in mind in any way when I wrote it.” When Boni & Liveright finally rejected The Torrents of Spring, Hemingway turned down offers from several other publishers and signed with Scribner’s.

As you see—he wrote Fitzgerald—I am jeopardizing my chances with Harcourt by first sending the Ms to Scribner and if Scribner turned it down It would be very bad as Harcourt have practically offered to take me unsight [sic] unseen. Am turning down a sure thing for delay and a chance but feel no regret because of the impression I have formed of Maxwell Perkins through his letters and what you have told me of him. Also confidence in Scribners and would like to be lined up with you…. Well, so long. I’m certainly relying on your good nature in a lousy brutal way.

Though the feeling between them later became less friendly, Fitzgerald never lost his deep admiration for Hemingway’s talent; he paid generous tribute to it in “Handle with Care”: “… a third contemporary had been an artistic conscience to me—I had not imitated his infectious style, because my own style, such as it is, was formed before he published anything, but there was an awful pull toward him when I was on a spot.” As soon as Hemingway had signed with Scribner’s Fitzgerald began to fuss over his work like a maiden aunt. He was particularly worried about The Sun Also Rises,and Hemingway took to teasing him about his own plans for The World’s Fair:

If you are worried [The Sun Also Rises] is not a series of anecdotes—nor is it written very much like either Manhattan Transfer nor Dark Laughter…. The hero, like Gatsby, is a Lake Superior Salmon Fisherman. (There are no salmon in Lake Superior) The action all takes place in Newport, R. I. and the heroine is a girl named Sophie Irene Loeb who kills her mother. The scene in which Sophie gives birth to twins in the death house at Sing Sing where she is waiting to be electrocuted for the murder of the father and sister of her, as then, unborn children I got from Dreiser but practically everything else in the book is either my own or yours. I know you’ll be glad to see it. The Sun Also Rises comes from Sophie’s statement as she is strapped into the chair as the current mounts.

He came down to visit the Fitzgeralds at Juan-les-Pins in August, much depressed by his marital difficulties. He brought with him a carbon of The Sun Also Rises, and he and Fitzgerald discussed it at great length. When he got back to Paris he wrote: “I cut The Sun to start with Cohn—cut all that first part made a number of minor cuts and did quite a lot of re-writing and tightening up. Cut and … in proof it read[s] like a good book.… I hope to hell you’ll like it and I think maybe you will. Have a swell hunch for a new novel. I’m calling it the World’s Fair. You’ll like the title.” In the final analysis Fitzgerald, almost as ambitious for Hemingway as for himself, decided that the fiesta, the fishing trip, and the minor characters were wonderful, but that in Jake Hemingway had bitten off “more than can yet be chewn between the covers of a book.” He disliked Lady Brett but was not sure his judgment of the character was not colored by his knowledge of the person it was based on.

In A Moveable Feast Hemingway goes to some pains to deny this account of Fitzgerald's association with the writing of The Sun Also Rises: 'The fall of 1925 he was upset because I would not show him the manuscript of the first draft of The Sun Also Rises.... Scott did not see it until after the completed rewritten and cut manuscript had been sent to Scribner's at the end of April' (p. 184). This statement cannot be absolutely true, since Hemingway's letter quoted in the text says quite specifically that he 'cut The Sun to start with Cohn-cut all that first part, etc.' after his visit to Juan-les-Pins. Fitzgerald may have been referring to this occasion when he wrote O'Hara in 1936: 'The only effect I ever had on Ernest was to get him into a receptive mood and say let's cut everything that goes before this'.

The Fitzgeralds had been in Juan-les-Pins since May, whenthey had taken a handsome house there called the Villa St. Louis. In a moment of enthusiasm Fitzgerald had told Perkins that they were “wonderfully situated in a big house on the shore with a beach and the Casino not 100 yds. away and every prospect of a marvelous summer.” Apart from a quick trip to Paris in June to have “Zelda’s appendix neatly removed,” they remained there into the autumn. Except that Zelda was ill for the rest of the year, they had a good time. The Murphys were there to give their fine parties, and sooner or later nearly everyone interesting seemed to turn up, from Grace Moore and Alexander Woollcott to Bishop and Donald Ogden Stewart. They dined with Grace Moore in Monte Carlo and were fascinated by the odd gentleman who was there for dinner in a leopard skin; not even Fitzgerald and Charles MacArthur had thought of that trick, though they spent much of the summer inventing similar ones. Once they planned to saw a waiter in two (with a musical saw to “eliminate any sordidness”) to see what was inside him, but Zelda told them it was not worth it, that they would only find old menus and tips and pencil stubs and broken china. Another time they lured the orchestra from the Hôtel Provençal to the Villa St. Louis, locked them in a room with a bottle of whiskey, and settled down outside the door for an evening of listening to their old favorites. The orchestra grew weaker and weaker, but Fitzgerald and MacArthur did not, and the poor musicians did not escape till dawn.

Adding Ben Finney to their staff they wrote and photographed, on the grounds of the Hôtel du Cap, a movie about a Princess Alluria, the wickedest woman in Europe. MacArthur wrote in an “incest theme” with the Japanese Ambassador as “the incestor,” and they spent a good deal of time thinking up unprintable titles to write on the walls of Grace Moore’s villa so that they could be photographed. “I complained and scrubbed once or twice,” she said, “but the new captions that then appeared were so much worse than the oldthat it seemed better to do with the four-letter words one knew than those one knew not of.”

These practical jokes, though in retrospect entertaining, were sometimes ominously destructive. On one occasion they raided a small restaurant in Cannes, carried off all its silverware, and kidnaped the proprietor and waiters. These victims they tied up and carried to the edge of a cliff, full of dire threats of murder. They did not stop until they had exhausted every device of terrorization they could imagine. The impulse to destroy visible behind this practical joking shows also in Fitzgerald’s social disturbances, as when, at a formal dinner in the Murphys’ garden, he suddenly rose and threw a ripe fig at the bare back of one of the guests. All the guests—including his victim—ignored him completely; he was left standing, alone and invisible, like a man in a nightmare. It defeated him completely, so that he appeared to be almost comforted later when Gerald Murphy remonstrated with him and he could be crestfallen and repentant. His dislike of the English must have been partly the result of their habit of suavely ignoring him when he tried to apologize for his bad behavior; they simply refused to admit that he had existed on such occasions. Perhaps he was compelled to such bad behavior by the conviction that it was innocent fun, and felt that it misfired because he did not belong and understand, as Gatsby’s efforts to give “interesting” parties misfired and, inexplicably, alienated Daisy.

There was little of the practical joker and none of the repentant in Zelda. She was even more striking in appearance now than she had been as a girl. Her hair had darkened to a “glossy dark gold”; Fitzgerald compared its color to a chow’s. Her whole face had matured, until even her mouth—“the cupid’s bow of a magazine cover”—only intensified the almost hawklike upper part of her face with its firm brow and nose and its remarkable eyes. She was always immaculate—“a fresh little cotton dress every day.” She talked very little. “I don’t believe,” Sara Murphy wrote of her long afterwards, “she liked very many people, although her manners to everyone were perfect.… Her dignity was never lost in the midst of the wildest escapades. Even that time at the Casino she was cool and aloof, and unconscious of onlookers. No one ever took a liberty with Zelda, as far as I know. It did upset her to hear Scott scolded or criticized—she flew to his defense and backed him up in everything.”

A good deal of injustice has certainly been done the Zelda of the twenties because she later went insane and it is difficult not to let the knowledge that she did so affect one’s view of what she was like before 1930. Many of their friends thought at the time that she saw more clearly than Fitzgerald how seriously their lives were getting out of hand and had greater strength of character in resisting dissipation than he did. There is much to support this view. To a friend who helped her get Fitzgerald home late one night during these years she said as she got out of the taxi, “Now I’ll have to start all over again,” and to his insistence on going out one night with the Callaghans, though he was drunk and exhausted, “Zelda said wearily, ‘You’d better let him go with with you. I’m going to bed.’ “Of their life at this time, Louis Bromfield said:

Of the two Zelda drank better and had, I think, the stronger character, and I have sometimes thought that she could have given it up without any great difficulty and that she was led on to a tragic end only because he could not stop and in despair she followed him. I have sometimes suspected that Scott was aware of this and that it caused remorse which did nothing to help his situation as it grew more tragic.

On the other hand, it could be maintained, as Hemingway maintained all his life, that Zelda was jealous of Fitzgerald’s achievement and used her ability to outdrink him to keep him from working. “Scott,” as Hemingway put it, “was afraid for her to pass out in the company they kept that spring and theplaces they went to. [“This spring she was making him jealous with other women. ”] Scott… had to drink more than he could drink and be in control of himself…. Finally he had few intervals of work at all.”

There is no doubt that Zelda often resented Fitzgerald’s concentration on work. Often enough she simply complained that it deprived them of fun and parties, but from the beginning she seems to have wanted also to compete with Fitzgerald by making a success as a writer or—later on—as a dancer or a painter: perhaps for people as attractive as they were at their best even the parties were occasions for competition. At the same time Zelda to some extent depended on Fitzgerald to provide the security for which, as a girl, she had depended on her father. People like the Callaghans were astonished when, at a moment of what appeared to them innocent gaiety for Zelda, Fitzgerald peremptorily ordered her home to bed: “her whole manner changed; it was as if she knew he had command over her; she agreed meekly…”

Where the relation between two people was as complicated as this one, perhaps all one can safely say is that at one time or another all these things were true of their marriage. In any event, during the middle years of the twenties, Zelda’s customary social demeanor was a brooding and fiery silence from which she would occasionally emerge to make some sudden gesture which, if often disturbing, was usually serious and symbolic. When Alexander Woollcott and Grace Moore’s fiancé, “Chato” Elizaga, were leaving for Paris at the end of the summer, there was a farewell dinner for them on the terrace at Eden Roc. After a considerable number of toasts, Zelda got up and said: “I have been so touched by all these kind words. But what are words? Nobody has offered our departing heroes any gifts to take with them. I’ll start off.” And she stepped out of her black lace panties and threw them toward Woollcott and Elizaga. Elizaga caught them and, announcing that he must perform an adequately heroic act m return for his lady’s favor, leapt from the rocks into theMediterranean. Everyone dashed down after him, and when order had been re-established, they suddenly became aware of Woollcott, completely naked, carefully donning his straw hat, lighting a cigarette, and walking slowly up the path to the hotel. They learned later that he had walked with great dignity but still naked into the lobby, up to the desk for his key, and on upstairs to his room. On another occasion, after she and Fitzgerald had been quarreling all evening, Zelda, instead of getting into the car when they were leaving, lay down in front of it and told Fitzgerald to run over her. Fitzgerald got into the car, apparently angry enough to do so, but it failed to start and their friends intervened.

With all these diversions, Fitzgerald naturally got little work done. When they had first reached the Riviera he had had a moment of optimism. “My book is wonderful,” he wrote Perkins. “I don’t think it’ll be interrupted again. I expect to reach New York about Dec. 10th with the ms. under my arm.” Two weeks later he was still going strong: “The novel… now goes on apace. This is confidential but Liberty, with certain conditions, has offered me $35,000 sight unseen. I hope to have it done in January.” But there is no further mention of the novel until December, when he answered a direct question from Perkins by saying, “My book [is] not nearly finished.” He did not write a single story between February, 1926 (when he wrote “Your Way and Mine” for The Women’s Home Companion), and June, 1927 (when he wrote “Jacob’s Ladder” for the Post). This failure, together with his failure to complete the novel, effectively canceled the profitable arrangement with Liberty. As always when he was not working, he was depressed, now, however, not simply because of his failure to write serious fiction, or indeed, to write at all; he also felt that he was steadily deteriorating. “I wish I were twenty-two again,” he said, “with only my dramatic and feverishly enjoyed miseries. You remember I used to say I wanted to die at thirty—well, I’m twenty-nine and the prospect is still welcome. My work isthe only thing that makes me happy—except to be a little tight—and for these two indulgences I pay a big price in mental and physical hangovers.” As if to demonstrate how persistent this mood was, he wrote Perkins two months later: “If you see anyone I know tell ‘em I hate ‘em all, him especially. Never want to see ‘em again. Why shouldn’t I go crazy? My father is a moron and my mother is a neurotic, half insane with pathological nervous worry. Between them they haven’t and never have had the brains of Calvin Coolidge. If I knew anything I’d be the best writer in America”—“which isn’t saying a lot,” he added when he recurred to this subject in another letter.

But if coming home, as he said, revolted him as much as the thought of remaining in France, they nonetheless made up their minds to return to America. Zelda was ill, their morale was badly shaken, and their money was running out, for “that was a period,” as one of their friends said, “when [Scott’s] pockets were always full of damp little wads of hundred franc notes that he dribbled out behind him wherever he went the way some women do Kleenex.” Fitzgerald saw nothing to do but flee, and they sailed for America from Genoa on the Conte Biancamano on December 10. It was an unhappy return. They did not have the money they had planned, three years earlier, to Save before they came home; the manuscript of Fitzgerald’s novel was not under his arm. If he still appeared, at thirty, to be a “stocky, muscular, clear-skinned [young man] with wide, fresh, green-blue eyes” and blond hair, who announced boldly to the press on his arrival in New York that “he [had] nearly completed a novel… which deal[t] with Americans in Europe,” he felt himself to be a man who for over two years had done no serious work and very little work of any kind, who was leading a self-indulgent life, a man in whom as in Dick Diver, “The change came a long way back—but at first it didn’t show. The manner remains intact for some time after the morale cracks.”

Next chapter 11

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).