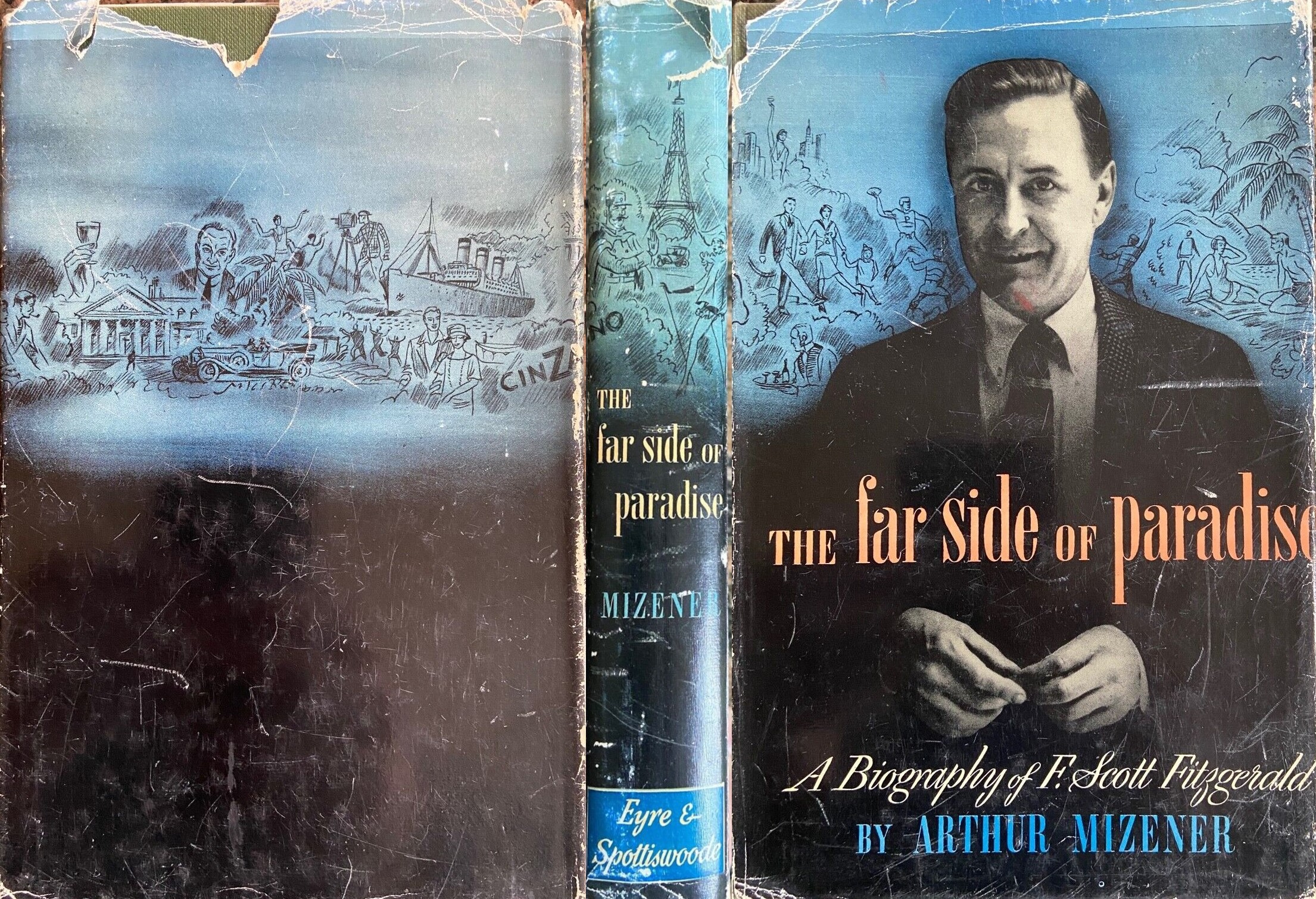

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter VIII

Because of the tension of the winter in St. Paul, they decided to visit New York as soon as Zelda could leave the baby. “I never knew,” Fitzgerald wrote Perkins, “how I [y]earned for New York.” In the middle of March they arrived at the Plaza and plunged into a party which did not end until they got back to St. Paul at the beginning of April. “I was sorry our meetings in New York were so fragmentary,” Fitzgerald wrote Wilson afterwards. “My original plan was to contrive to have long discourses with you but that interminable party began and I couldn’t seem to get sober enough to be able to tolerate being sober. In fact the whole trip was largely a failure.”

At the same time The Beautiful and Damned was getting a mixed reception from the critics and a reception from the public which, if excellent by most people’s standards, was not up to what Fitzgerald had anticipated. By the time the book was published he had borrowed from Scribner’s $5643, the amount he would make from the sale of 18,810 copies (the figures are his own, for it was part of his ceaseless anxiety at the mysterious way his debt piled up that he kept minute track of it). An advance of $5600 to an author so popular as Fitzgerald was not extravagant, but to the writer who had pressed hard to finish a second novel quickly and had driven himself since he returned from Europe to produce enough short stories to keepout of debt, it seemed a defeat. “It is not,” he wrote Perkins, “that I have not been working. The situation is due to the Metropolitan. A finished story is being held up by Reynold’s [the literary agent’s] office until they pay for the one before.” This is more a confession of bewilderment than an explanation. What was the man who had already had, with the sale of the serial rights and the advance from Scribner’s, two thirds of the profits from a book which was not yet even published doing in a position where he needed $1000 at once because payment for a story was delayed a week or ten days? Even if he could maintain his rate of production without damaging his development as a writer, he could hardly assume that his popularity would remain at its peak or that he would never write anything which did not sell beyond expectations. Yet he seemed unable to reduce his expenses. “My play,” he concludes a little hopelessly in the letter I have been quoting from, “left here yesterday and I feel, as I usually do that I’ll soon be out of the woods. …”

The disappointing sales of The Beautiful and Damned convinced him that it had been “a dire mistake to serialize it,” and if any number of the critics were working from the serial version rather than the book, it was, for as Fitzgerald wrote Perkins, “Hovey [the editor of Metropolitan Magazine] has clipped and cut it up abominably.” Everything in the ending, for example, which emphasizes the deterioration of Anthony and Gloria has been cut in order to reduce, as far as possible, the irony of the “happy” ending (The following passages in the book do not appear in the serial version: pp. 405-14, 430-33, 441-42, 444 (from 'Turning about from the window...' to 'Well, things would be different'). The final paragraph of the serial version was cut by Fitzgerald at Zelda's suggestion). Fitzgerald had apparently suspected the worst when he sold the serial rights, for when Boyd was shown the manuscript of the book in September and exclaimed over its superiority to the first installment he had read in the Metropolitan Magazine, Fitzgerald looked at him “in rather a funny way” and said: “Well, they bought the rights to do anything they liked with it when they paid for it.” (Fitzgerald had borrowed $3400 from Reynolds in May 1921, to pay for their trip abroad. At that time he had wanted to sell the serial rights to THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED to repay this loan and therefore granted Metropolitan the right to cut. See F. Scott Fitzgerald to Harold Ober, May 2, 1921.) He was convinced enough of the evils of serialization by this experience that, when he asked $15,000 for the serialrights to Gatsby and was offered only $10,000 (by College Humor), he turned the offer down. Scribner’s optimistically printed a third edition of The Beautiful and Damned of 10,000 copies a month after publication when the sale was only 33,000 and Perkins was saying that he “doubted if we can hope that it will be an overwhelming success now…” A year after publication the sales had barely exceeded—by 3000-odd copies—the original printing of 40,000 “not,” in Fitzgerald’s judgment, “an inspiring sale.”

When he got back to St. Paul he settled down at once to selecting and revising the stories for his next book of short stories. In his spare time he wrote and directed the St. Paul Junior League show. His piece, called “The Midnight Flappers,” presented a carbaret scene in which there appeared “a southern flapper [played by Zelda], a society flapper, a very tough flapper and a regular flapper—with a background of Yale ‘rowboat-men,’ prohibition agents, well-bred inebriates and cake-walkers.”

His book of stories, Tales of the Jazz Age, was published in September. As with Flappers and Philosophers, which had followed This Side of Paradise, he had to dig deep to find enough stories to fill the book. He put in everything he had written since the previous volume except “Popular Girl” and “Two for a Cent” and reached back further for three pieces he had rejected when Flappers and Philosophers was collected, “The Camel’s Back,” “Porcelain and Pink,” and “Mr. Icky.” Thus there was some grounds for The Dial’s severe assertion that in the collection Fitzgerald was exploiting “the dross in his first book”; with his queer honesty he said as much himself, remarking of “Jemina” that “it seems to me worth preserving a few years” and of “The Camel’s Back” that he liked “it least of all the stories in this volume.” Of the book as a whole, he said it was for “those who read as they run and run as they read.” But he was not to be persuaded by the argument that sales would be injured when Perkins, in anunexpected outburst, suddenly launched an attack on “Tarquin of Cheapside”; “the crime,” Perkins said, “is a repugnant one for it involves violence, generally requires unconsciousness, is associated with negroes.” On the other hand, Fitzgerald’s feelings about the quality of some of these stories, though frankly enough expressed, did not prevent his publishing them and observing that “[Tales of the Jazz Age] will be bought by my own personal public, that is by the countless flappers and college kids who think I am a sort of oracle…. The splash of the flapper movement was too big to have quite died down—the outer rings are still moving.” About this he was quite right, for while The Beautiful and Damned was doing worse than This Side of Paradise had, Tales of the Jazz Age did slightly better than Flappers and Philosophers.

If Tales of the Jazz Age was a badly watered book it was «till a better one than Flappers and Philosophers. The latter had not contained more than one or two stories worth looking at twice, “The Ice Palace” with its fine climactic scene,—and “The Cut-Glass Bowl,” which, in spite of its tendency to overdramatize, has what Fitzgerald himself called “that touch of disaster” common to his best stories. “Dalyrimple Goes Wrong” has the genuineness of all the stories he based on his own inner experience. But the rest are popular stories which are not the worst of their kind only because of Fitzgerald’s verve.

There are more good stories in Tales of the Jazz Age; there is “The Lees of Happiness” with its haunted, tragic version of a possible Fitzgerald life—and its ironic description of his own short stories as “passably amusing stories, a bit out of date now, but doubtless the sort that would then have whiled away a dreary half hour in a dental office”; there are “May Day” and “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” where Fitzgerald’s beautifully defined feeling about limitless wealth is only slightly marred by smart writing; there is “The JellyBean” with its delicate sense of social position; and there are the two fantasies, “O Russet Witch” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” both slight in idea but full of life. The strength of these stories is the precision and genuineness of their feeling. Their weakness is that Fitzgerald was seldom able, at this point in his career, to reason out what he felt. The controlling idea is never clearly enough defined to provide a meaningful structure, nor has it, usually, any close relation to the story’s sentiments. His habit was to vamp passages of generalization here and there in a story and round it off with a piece of popular philosophizing, as he does in “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” or simply to let a mechanical plot serve as a framework for the sentiments. About this time Edmund Wilson, with his usual penetrating understanding of Fitzgerald’s work, wrote him of the first version of his play, The Vegetable: “I think you have a much better grasp on your subject than you usually have—you know what end and point you are working for as isn’t always the case with you.”

Since the previous fall Fitzgerald had been working on the play he had first projected two years before. In January he had written Perkins that he was in the midst of “an awfully funny play that’s going to make me rich forever. It really is. I’m so damned tired of the feeling that I’m living up to my income.” In February he finished the play and began trying it on various producers; they were uninterested. By the end of May he had revised it and tried several places, again without success. In July he did another revision of it and found a tentative name for it, Gabriel’s Trombone. In August Sam Harris was considering this new version.

They had moved out to the lake in June, this time to the White Bear Yacht Club; living at the club spared Zelda the uncongenial task of housekeeping and Scott’s irritating fidgets about household noises; and at the club they were conveniently at the location of the summer’s parties. Meanwhile Fitzgeraldloafed; he had temporarily exhausted his material. In the spring he played with the idea of a novel about the Middle West and New York in 1885; “it will concern less superlative beauties than I run to usually,” he wrote Perkins, “and will be centered on a smaller period of time. It will have a catholic element.” But he soon lost interest in this idea and began to dicker “with 2 men who want to do Paradise as a movie with Zelda and I in the leading rolls.” Perkins was horrified at the idea, and Fitzgerald tried to reassure him by promising that it would be his “first and last appearance positively.” That scheme too came to nothing. He talked so much about his lack of material that one day Heywood Broun, in New York, came around to see John Bishop to suggest Fitzgerald might like to do a part-time column for The World at $125 a week if he wanted a chance to look for material; Broun estimated the job would take half Fitzgerald’s time. That Broun should have supposed Fitzgerald could afford to sell half his working time at this price is evidence of the sincerity of his conviction that the life portrayed in Fitzgerald’s books did not exist.

If Fitzgerald loafed partly because he had exhausted his material, he did so partly, too, because of the belief he and Zelda shared that if you were good enough you not only could live according to the hedonistic code of the twenties but would probably turn out all the better for doing so. Zelda stated their belief without qualification:

I should think that fully airing the desire for unadulterated gaiety, for romance that she knows will not last, and for dramatizing herself would make [a woman] more inclined to favor the “back to the fireside” movement than if she were repressed until age gives her those rights that only youth has the right to give.

I refer to the right to experiment with herself as a transient, poignant figure who will be dead tomorrow. … I see no reason for keeping the young illusioned. Certainly disillusionment comes easier at twenty than at forty—the fundamental and inevitable disillusionments, I mean.

Fitzgerald’s less assured version of this belief was, as he put it in a newspaper article:

“What kind of a wife will the girl make who has had numerous petting parties?”

The answer is that nobody knows what kind of a wife any girl will make.

“But,” they continue, “won’t she be inclined to have petting parties after she’s married?”

In one sense she will. The girl who is a veteran of many petting parties was probably amorously inclined from birth….

But it may even be true that petting parties tend to lessen a roving tendency after marriage. A girl who knows before she marries that there is more than one man in the world but that all men know very much the same names for love is perhaps less liable after marriage to cruise here and there seeking a lover more romantic than her husband.

This was the code of the twenties; the Fitzgeralds believed in it sincerely and conducted their lives according to its precepts. No doubt it has faults of moral naïveté and sentimentality. But neither these faults nor the fact that experimenting with themselves led the Fitzgeralds to habits of self-indulgence and disorder rather than back to the fireside should make one forget the circumstances which led them to adopt it. The hypocrisy, the ignorance, and the cant about “experiments noble in purpose” of the moralists the twenties objected to were something worse than what the rebels believed in as an alternative. To that alternative the Fitzgeralds committed themselves. They were going to “air the desire for unadulterated gaiety” on the conviction that “youth’s a stuff will not endure” and then, duly disillusioned, settle into a resigned old age. Fitzgerald was even inclined for a while to think that he would commit suicide at thirty, though he gradually advanced the date until—sadly enough for he never saw it—he settled on fifty. “‘Up to forty-nine it’ll be all right,’ I said. ‘I can count on that. For a man who’s lived as I have, that’s all you could ask.’”

In October, because of the play and because they longed for New York again, they decided to move back there. They went on at the beginning of October, but were so involved in going to see the Greenwich Village Follies—where the curtain by Reginald Marsh included a view of Zelda diving into a fountain—and otherwise catching up that it was the middle of the month before they finally settled on a $300-a-month house on Gateway Drive in Great Neck and Zelda went back to St. Paul to bring the baby and her nurse east. They bought a secondhand Rolls-Royce (their cars were always romantic but secondhand) and settled down to New York. “… with the impunity of their years,” as Ernest Boyd said, “they can realize to the full all that the Jazz Age has to offer, yet appear as fresh and innocent and unspoiled as characters in the idyllic world of pure romance. The wicked uncle, Success, has tried to lead these Babes in the Wood away and lose them, but they are always found peacefully sleeping in each other’s arms. The kind fairies have watched over them, as they wandered in the city underwoods, from Palais Royal to Plantation, from Rendezvous to Club Gallant, with many a détour before the delayed and ever-miraculous departure for Great Neck, and safe arrival there in the most autonomous automobile on Long Island.”

There is some exaggeration in Boyd’s account, yet it is substantially true. If they were more worldly people than they had been two years before in New York, they were still eager and enthusiastic and Fitzgerald’s combination of brashness and honesty was disarming. In “The Crime in the Whistler Room” (Discordant Encounters, pp. 180-81), Edmund Wilson describes one of his characters as “an attractive young man with a good profile, who wears a clean soft shirt and a gay summer tie, but looks haggard and dissipated... His manner ... alternates between too much and too little assurance, but there is something disarmingly childlike about his egoism.” Opposite this passage in the margin of his own copy of the play Fitzgerald wrote: “Bunny on Papa.” But Mr. Wilson says: “My conception of the character was quite distinct from Scott. Scott, for example, though he sometimes looked pale, could not be described as haggard.” It shows clearly in the portrait Edmund Wilson did of him in “The Delegate from GreatNeck.” When Van Wyck Brooks in that dialogue points out the characteristic American impoverishment he thinks he sees in Henry James’ career, Fitzgerald is made to say: “The Puritan thing, you mean. I suppose you’re probably right. I don’t know anything about James myself. I’ve never read a word of him.” A moment later he is explaining to Brooks that “I find that I can’t live at Great Neck on anything under thirty-six thousand a year and I have to write a lot of rotten stuff that bores me and makes me depressed.” But when Brooks protests that no writer needs to live on such a scale, he says, “Well, don’t you think, though, that the American millionaires must have had a certain amount of fun out of their money?… Think of being able to give a stupendous house party that would go on for days and days, with everything that anybody could want to drink and a medical staff in attendance and the biggest jazz orchestras in the city alternating night and day! I must confess that I get a big kick out of all the glittering expensive things.” This outburst is followed by an invitation to Brooks to attend a party at Great Neck which will include Gloria Swanson, Sherwood Anderson, Dos Passos, Marc Connelly, Dorothy Parker, Rube Goldberg, Ring Lardner, and “a man who sings a song called, Who’ll Bite your Neck, When my Teeth are Gone?” “Neither my wife nor I knows his name,” he adds, “but his song is one of the funniest things we’ve ever heard!” “I wonder,” Hemingway wrote him a little later, “what your idea of heaven would be—A beautiful vacuum filled with wealthy monogamists all powerful and members of the best families all drinking themselves to death.”

They gave many parties, for as Fitzgerald remarked ruefully, “it became a habit with many world-weary New Yorkers to pass their week-ends at the Fitzgerald house in the country.” He and Zelda wrote a set of Rules for Guests at the Fitzgerald House. “Visitors,” it said, “are requested not to break down doors in search of liquor, even when authorized to do so by the host and hostess”; and, “Week-end guests are respectfully notified that the invitations to stay over Monday, issued by the host and hostess during the small hours of Sunday morning, must not be taken seriously.” These rules were only partly a joke, for a Fitzgerald party was likely to go on indefinitely. It might begin at some night club. There would be, perhaps, a bootlegger, “some probably intimidated and indignant friends from the hinterland,” a mixed collection of literary and theatrical people, and a few unaccountable strays like the man who sang “Who’ll Bite your Neck, When my Teeth are Gone?” Burton Rascoe once described the course of such an evening:

Fitzgerald showed us some card tricks he had learned from Edmund Wilson, Jr., told us the plot of “the great American novel” which he is just writing (and asked me not to give it away), and the plots, too, of some new scenarios, and made a speech, and sang a pathetic ballad of his own composition, “Dog, Dog, Dog.” Mencken kept calling him Mr. Fitzheimer and Nathan made him as dispirited as words very well can by kidding him about one of the plots he was relating….

By the time they were ready to pick up the second-hand Rolls somewhere near the Plaza and go home, they would have attracted a crowd of friends for the confused drive to Great Neck.

The journey to and from Great Neck was always an adventure, for a car was not a safe instrument in the hands of either of them. Once Fitzgerald drove Max Perkins straight into a pond instead of following the curve of the road “because it seemed more fun”; Zelda got herself arrested as “the Bob-haired Bandit,” and once she drove slowly out of a side road in front of a car which missed her only by a heroic effort. When her passenger asked breathlessly if she had not seen it, she said, Oh yes, that she had. (Fitzgerald drove Perkins into the pond in July, 1923, according to his Ledger; the story is told in John Mosher's 'That Sad Young Man' (the New Yorker, April 17, 1926), where Perkins is made a 'publicity manager' and the pond a lake. A year later Perkins wrote Fitzgerald: 'I thought that night a year ago that we ran down a steep place into a lake. There was no steep place and no lake... Durant took his police dog down to the margin of that puddle of a lily pond,—the dog waded almost across it;—and I'd been calling it a lake all these months. But they've put up a fence to keep others from doing as we did.' (Perkins to F. Scott Fitzgerald, August 8, 1924.) The Bob-haired Bandit story is in 'Echoes of the Jazz Age' (The Crack-Up, p. 21); the other story I had from Edmund Wilson) Yet somehow, in spite of their driving and in spite of the law, they always managed the return to Gateway Drive, where it was customary for their man to find them sleeping quietly on the front lawn when he got up in the morning.

This life made the proper operation of a household difficult at best, and, as Fitzgerald said of himself, “… I have [never] been able to fire a bad servant, and I am astonished and impressed by people who can.” They had three such servants at Great Neck. It was an expensive domestic arrangement. Nor were the parties cheap, nor the liquor, nor what Ernest Boyd called Fitzgerald’s “embarrassing habit of using his check book for the writing of inexplicable autographs in the tragic moments immediately preceding his flight through the weary wastes of Long Island.” They spent $36,000 during their first year at Great Neck.

Yet at the center of all this confusion, there persisted in Fitzgerald the hard core of his dead earnestness about being a good writer. It showed itself, perhaps a little incongruously, on the occasion of Dreiser’s literary party. Dreiser, who seldom entertained or went out, appears to have had no idea how to go about giving such a party. He had his guests—Mencken, Van Vechten, Ernest Boyd, Sherwood Anderson, Llewelyn Powys, and a good many others—seated in straight-back chairs lined along the wall like chairs in a ballroom. Evidence as to the refreshment provided is mixed, but there appears to have been little or nothing to drink. Dreiser seems to have neither introduced his guests to one another nor attempted in any way to draw them together, and the party was dying a lingering death when Fitzgerald arrived. With his deep admiration for anyone who had talent and integrity as a writer, Fitzgerald looked up to Dreiser with awe. “I consider H. L. Mencken and Theodore Dreiser,” he said, “the greatest men living in the country today.” He had determined, therefore, to make a fitting gesture for the occasion of his first meeting with so great a writer and had spent considerable time obtaining a really good bottle of champagne for Dreiser. Its purchase had involved some judicious sampling. Nonetheless, when he reached Dreiser’s, he managed to struggle up to his host and deliver a formal expression of his admiration. He then handed over the bottle of wine. Dreiser put it carefully in the icebox and the party sank back into its previous torpor. After an hour or so everyone gave up hoping that Dreiser would ever get the champagne out again, and so, one by one, the guests dragged themselves away. Like all literary anecdotes frequently repeated, this one has become badly confused. Sherwood Anderson says Fitzgerald never got past the door; Burton Rascoe says he came in and 'teetering from one guest to another, inquiring which was Dreiser, he finally found his host...' There are many other discrepancies. The party seems to have taken place in January, 1923. See Ernest Boyd, Portraits: Real and Imaginary, pp. 221-22; Llewelyn Powys, The Verdict of Brindlegoose, pp. 131-32; Burton Rascoe, We Were Interrupted, pp. 229-302; Sherwood Anderson, Memoirs, pp. 335-37. Anderson's version, with its unique details, its suspiciously stylized dialogue, and its neat tie-up with a previous experience of Anderson's own with Dreiser appears the least trustworthy of any of these accounts

Similarly, on another occasion, he insisted on paying tribute to Edith Wharton. Finding himself at Scribner’s while she was there and able to persuade no one to intrude on Mrs. Wharton to the extent of introducing him, he burst in on a conference in Mr. Scribner’s own office and introduced himself to her. Indeed, he is reported to have thrown himself at her feet and said: “Could I let the author of ‘Ethan Frome’ pass through New York without paying my respects?”

Episodes like these have a ludicrous aspect which Fitzgerald sometimes half consciously cultivated, but his admiration for real literary achievement was dead earnest. Admiring serious writers as he did, he never ceased to want to emulate them, “to pit himself,” as Edmund Wilson put it, “against the best in his own line that he knew.” He was presently to show his seriousness about being a good writer with The Great Gatsby, and to demonstrate his almost pathetic admiration for real literary distinction in his response to its reception. Even his play, The Vegetable, though clearly written with an eye on the Big Money, was written with care and literary ambition.

In September, 1922, The Vegetable had been rejected again and as soon as they were settled in Great Neck Fitzgerald sat down to rewrite it completely for the third time. Late in April it was finally accepted by Sam Harris and scheduled to go into rehearsal in October. Meanwhile Fitzgerald had begun to work rather casually on a new novel. In March he hadsold the movie rights to This Side of Paradise for what was then the considerable sum of $10,000, so that there was no immediate financial pressure on him; his notes through this period consist mainly of “Dec. [1922] A series of parties…. Jan. [1923] Still drunk…. April. Third Anniversary. On the wagon…. July. Intermittent work on novel. Constant drinking…. Aug. More drinking.” At the end of the summer he tried to settle down and got some steady work done on his novel. But in October The Vegetable went into rehearsal and, like many authors, Fitzgerald became fascinated by the process of production, spending his days at the theater watching and arguing and his nights revising what seemed not to be going well in rehearsals. His excitement rose to fever pitch through November; he was delighted with Ernest Truex in the lead and sure the play was going to be a great success. In the middle of November they opened at the Apollo Theater in Atlantic City and The Vegetable flopped dismally. “It was,” wrote Fitzgerald, “a colossal frost. People left their seats and walked out, people rustled their programs and talked audibly in bored impatient whispers. After the second act I wanted to stop the show and say it was all a mistake but the actors struggled heroically on. There was a fruitless week of patching and revising, and then we gave up and came home.”

The Vegetable is not nearly so bad as this history suggests. The political fantasy in the second act is more inventive than anything in Of Thee I Sing, which is based on a similar idea and was to be a hit a few years later (Fitzgerald believed to his dying day that Kaufman had stolen his idea). Perhaps both plays suffer from the fact that they have nothing to say on the subject of politics except that politics are hopelessly absurd. This was the conventional attitude of the period, but it is too inclusive and undefined an attitude to make for pointed satire. Fitzgerald’s play also suffers because in writing political satire at all he was working at something which did not draw on any of his deeper resources. He had a vein of light comedywhich served him for popular stories and he shared superficially his period’s feelings about politics. But these feelings were not among the ones he had really made a part of himself, and his expression of them never had the intensity and precision he achieved when his feelings were deeply involved. Moreover, he was always in danger when he was writing fantasy, for he was inclined to use material which was more extravagant than its point justified and to make so much fantastic that nothing seemed remarkable. There are, of course, exceptions to this general statement, but even in Fitzgerald’s partially successful fantasies—such as “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” or “A Short Trip Home,” or “The Adjuster”—the fantasy itself is often the weakest thing. These stories succeed by virtue of the intensity of their feeling, usually of human evil, rather than because of their fantasy, which is likely to hover uneasily between symbolism and allegory, as it does in “The Adjuster.” Between the tendency of his fantasy to overreach itself and the vagueness of the satire’s assertion about politics, The Vegetable’s second act is never more than mildly amusing.

But political satire is not the main point of Fitzgerald’s play; his main point is that the American dream of rising from newsboy to President is ridiculous and that the Jerry Frosts of this world are far happier being the postmen nature made them than being presidents. “The spirit [of the play is],” as one reviewer remarked, “an obvious act of deference to Mencken’s virulent contempt for the American people.” It was a curious point for Fitzgerald to be making, and his assertion of, Jerry’s triumph as a postman in the last act is unconvincing because he is so successful in making Jerry a hopeless cipher in the first act. This first act is the strongest in the play; it contains a good deal of sharp observation of Jerry and “Charlit” Frost’s domestic life. After all the deficiencies of the play have been considered it remains a good deal more shrewd and amusing than most things of its kind. Perhaps the worstthat can be said about it is that it fatally compromised its hopes of Broadway success by its seriousness and originality and at the same time weakened the point it wanted to make about the middle-class civilization of America by its concessions to the Broadway conventions for successful farce.

When Fitzgerald got back to Great Neck after the failure of The Vegetable he found himself, to his profound astonishment, $5000 in debt. He did the only thing he knew to do in these circumstances; he went on the wagon, retired to the large bare room with the oil stove over their garage, and set to work to write himself out of his financial plight. The task was made no easier by the fact that the previous January he had, for $1500, sold Hearsts International an option on all his stories. This contract had been the result of a considerable struggle on the part of Carl Hovey, who greatly admired Fitzgerald’s stories, against the opposition of everyone “from W. R. down.” When Fitzgerald submitted “Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr—nce of W—les,” there was such an outcry “upstairs” that Hovey had to give up the fight. Fitzgerald then had what he called “a grand fight” with the Hearst organization and the contract was cancelled.

Between November and April, when he got out of debt and enough ahead so that he felt he could go back to his novel, Fitzgerald produced eleven stories and earned over $17,000. It had been a nerve-racking drive of working for long stretches at twelve hours a day and, often, producing a story at one sitting. “But I was,” said Fitzgerald with restraint, “far from satisfied with the whole affair. A young man can work at excessive speed with no ill effects, but youth is unfortunately not a permanent condition of life.” It was six months before he was able to say: “I have got my health back—I no longer cough and itch and roll from one side of the bed to the other all night and have a hollow ache in my stomach after two cups of black coffee. I really worked hard as hell last winter—but it was all trash and it nearly broke my heart aswell as my iron constitution.” This account is exaggerated, for Fitzgerald was, like so many writers, always something of a hypochondriac, and he was inclined to become more so whenever his work went badly. Yet the winter did put a severe strain on him, and it was in January of 1923 that he first began to suffer from insomnia and to put himself to sleep with the daydream about being a football player or a general which he describes in “Sleeping and Waking.” At the same time he took a sort of pride in his remarkable burst of energy and its financial rewards and in what he thought was Zelda’s inability to appreciate what he was doing. These feelings come out in “Gretchen’s Forty Winks,” written in the middle of his big push.

While they were living at Great Neck Fitzgerald and Ring Lardner became intimate friends. Their friendship was an odd but very close one; they drank and argued together till dawn again and again and got into some epic scrapes. One night in May, 1923, for example, they decided they wanted to meet Conrad and express to him their admiration. Conrad had come to this country on a much publicized visit at the height of his ‘ fame and was staying with his publisher, Doubleday, at Oyster Bay. But he was shy and suffering from gout and he went nowhere and saw almost nobody. Fitzgerald and Lardner devised a typical Fitzgerald scheme for breaking through this barrier. They would go to the Doubledays and perform a dance on the lawn. Their notion was that this dance would make Conrad see he was dealing with men who knew how to turn an amusing, yet delicate and sincere, compliment and that from there everything would be clear sailing. But before Conrad could be properly charmed they found themselves thrown off the Doubleday estate for creating a drunken disturbance.

It would be difficult to say just what there was about Fitzgerald which appealed to the bitterness and despair which show clearly in Lardner’s best stories and which Fitzgerald himself tried to define. What appealed to Fitzgerald in Lardner, though not simple, can be partly understood because Fitzgerald wrote about it carefully. He saw Lardner, as he said after Lardner had died, as “proud, shy, solemn, shrewd, polite, brave, kind, merciful, honorable—with the affection these qualities aroused he created in addition a certain awe in people… Under any conditions a, noble dignity flowed from him, so that time in his company always seemed well spent.” There is no doubt about Lardner’s possession of these qualities or about his talent for friendship; it shows in everything he said and did, in the marvelous letters he wrote and in the funny things he printed about his friends. In the parody he did of the “intimate glimpses” of famous writers, “In Regards to Genius,” he wrote of Fitzgerald, for example:

Another prominent writer of the younger set is F. Scott Fitzgerald. Mr. Fitzgerald sprung into fame with his novel This Side of Paradise which he turned out when only three years old and wrote the entire book with one hand. Mr. Fitzgerald never shaves while at work on his novels and looks very funny along towards the last five or six chapters. His hobby is leashing high bred dogs and when not engaged on a book or story, can be seen most any day on the streets of Great Neck leashing high bred dogs of which there is a great number. He cannot bear to see any of them untied.

That a man with these personal qualities and undoubted gifts should, out of obscure despair, destroy himself, and, because he was proud, destroy himself so quietly that he never admitted he was doing it—this was a situation bound to fascinate Fitzgerald. With all his ebullience and self-dramatization Fitzgerald had a deep respect for the kind of pride and restraint he felt in Lardner. Moreover, his fear of emotional bankruptcy in his own life, of a state in which he could care for nothing enough any more to go on with it, was growing rapidly at this time. “Being in the town where the emotions of my youth culminated in one emotion,” he wrote Perkins from Montgomery, “makes me feel old and tired. I doubt if, after all, I’ll ever write anything again worth putting in print.”

The more he felt he was deteriorating—and the deliberate drive to make money during the winter of 1923-24 seemed to him as destructive as the dissipation which preceded it—the more he was fascinated by a man who seemed able to preserve his pride and dignity in complete emotional bankruptcy. This achievement represented a heroism which Fitzgerald respected all the more because he realized how impossible it would be for him.

While he knew Lardner he alternated between efforts to shake him out of indifference toward his gifts and a kind of baffled admiration for Lardner’s stoicism. After struggling unsuccessfully to get Lardner to tackle a big subject, he finally persuaded him to take an interest in a collection of stories. “My God!” he wrote ten years later in undiminished astonishment, “he hadn’t even saved them—the material of ‘How to Write Short Stories’ was obtained by photographing old issues of magazines in the public library! “ Into looking up these stories, persuading Max Perkins to publish them, finding a title for the book, and getting Lardner to take a mild interest in the whole business Fitzgerald threw himself with all the generous enthusiasm he always had for a writer he admired. When Fitzgerald admired a writer his generosity was unlimited. His advocacy of Hemingway is a case in point, and at about the same time he was pressing Lardner to publish, he succeeded, by nagging furiously at Perkins, in getting Scribner's to publish Thomas Boyd's Through the Wheat, though they had originally rejected it. Though he was disappointed in Boyd's later work, he always believed he had been right about Through the Wheat. Lardner’s contemporary reputation as a serious writer was largely Fitzgerald’s work, though even he could not keep Lardner at it after he had left for Europe, and Perkins gradually gave up pressing Lardner for material.

Much later, when Fitzgerald came to write the story of his own emotional bankruptcy in Tender Is the Night, he used what he understood of Lardner’s attitude for Abe North, and all through Tender Is the Night there runs a persistent but unemphatic suggestion of the resemblance between Dick Diver, whose destruction is Fitzgerald’s self-judgment, and AbeNorth; they are secret sharers. In the earlier versions of Tender Is the Night the portrait of Abe North is much more detailed than in the printed book and one passage from a description of this character in the earlier version is worth quoting because a key phrase from it remained in Fitzgerald’s mind to reappear again more than a decade later in the passage I have quoted above from his tribute to Lardner: “In spite of the amount of liquor he was carrying a great, solemn dignity flowed from him—a dignity that would have been heavy had he been less modest. But Francis guessed that behind the face that was like a cathedral there was something in him that was bitter and bored.”

By April, 1924, Fitzgerald found himself at last out of the woods financially and able to return to the novel he had put aside in the middle of the previous October. But before he could get much work done on it, he and Zelda suddenly decided that their life in Great Neck was impossible, financially and socially, and that they would go to France and “live on practically nothing a year.” They were escaping, Fitzgerald thought, “from extravagence and clamor and from all the wild extremes among which we had dwelt for five hectic years, from the tradesmen who laid for us and the nurse who bullied us and the couple who kept our house for us and knew us all too well. We were going to the Old World to find a new rhythm for our lives, with a true conviction that we had left our old selves behind forever—and with a capital of just over seven thousand dollars.” They would find, as Fitzgerald knew all too well by the time he wrote that, that they could not so easily leave their old selves behind, but for the moment they were full of optimism. Like Gatsby, Fitzgerald “wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving [Zelda]. His life had been confused and disordered since then, but if he could once return to a certain starting place and go over it all slowly, he could find out what that thing was.”

Lardner sent them off with a farewell poem to Zelda which concluded:

So dearie when your tender heart

Of all his coarseness tires

Just cable me and I will start

Immediately for Hyères.

To hell with Scott Fitzgerald then!

To hell with Scott his daughter!

It’s you and I back home again

To Great Neck where the men are men

And booze is ¾ water.

After a couple of weeks of great confusion they got settled temporarily in the Grimm’s Park Hotel at Hyères and set about finding a villa. “This is a strange hotel,” Zelda wrote Perkins, “—we are surrounded by invalids of every variety and all the native Hyèresans have goiter.” It was, Fitzgerald noticed in the guidebook a little too late, “the very oldest and warmest of the Riviera winter resorts” and there appeared to be nothing on the menu but goat’s meat. But by June they had found a satisfactory place to live at St. Raphaël, a large and handsome place with extensive gardens called the Villa Marie. There they settled for the summer. “Oh, we are going to be so happy away from all the things that almost got us but couldn’t quite because we were too smart for them!” says the hero of Save Me the Waltz when he and his wife move into a villa at St. Raphaël. They bought a Renault “à six chevaux,” Fitzgerald grew a mustache and gradually surrendered to the French barber’s idea of how his hair ought to be cut, and they soaked in the sun long hours on the beach. For a while things went along so well that Fitzgerald wrote Perkins optimistically, “We are idyllicly settled here and the novel is going fine—it ought to be done in a month….” They were planning to go home in the autumn when the book was finished.

But in July there was a serious crisis in their lives. When they had first come to St. Raphaël they had met a French aviator by the name of Edouard Josanne. He was a dark, romantic fellow with a classically handsome profile and curly black hair and he almost immediately fell deeply and openly in love with Zelda. This was a familiar experience for Fitzgerald though he never altogether accustomed himself to it. But when Zelda in her turn began to show an interest in Josanne it was another matter. “The head of the gold of a Christmas coin,” Zelda wrote of the character in Save Me the Waltz who is based on Josanne, “… broad bronze hands… convex shoulders… slim and strong and rigid….” The affair came to quick and violent climax by the middle of the month and, apparently after one or two noisy and undignified scenes set off by Fitzgerald, Edouard departed from St. Raphaël, leaving Zelda a long letter in French and his photograph. “It was the most beautiful thing she’d ever owned in her life, that photograph,” Zelda wrote in Save Me the Waltz. “What was the use of keeping it? … There wasn’t a way to hold on to the summer, no French phrase to preserve its rising broken harmonies, no hopes to be salvaged from a cheap French photograph. What ever it was that she wanted from [him], [he] took with him…. You took what you wanted from life, if you could get it, and you did without the rest.” There is a courage about this assessment of the experience which is typical of Zelda; there is also a disregard for its effect on anyone else which helps to explain Fitzgerald’s later feeling that “never in her whole life did she have a sense of guilt, even when she put other lives in danger—it was always people and circumstances that oppressed her.”

The effect of this experience on Fitzgerald was enormous. He had given himself completely to his feelings about Zelda, and if those feelings changed during the course of their marriage, he never imagined that he loved her less or she him. He had never acquired the twenties’ habit of tolerating casual affairs. He remained all his life essentially the boy who was shocked as an undergraduate by his classmates’ casual sex life; if he came to tolerate this kind of thing intellectually later, he never reconciled his feelings to it. Sexual matters were always deadly serious to him, a final commitment to the elaborate structure of personal sentiments he built around anyone he loved, above all around Zelda. His attitude was the attitude of Gatsby toward Daisy, who was for him, after he had taken her, as Zelda was for Fitzgerald, a kind of incarnation. “The emotions of my youth,” as he said, “culminated in one emotion,” his feeling for Zelda. It was the damage done to this structure of sentiments which was most disturbing in the Josanne affair. “… no one, I think,” as Lionel Trilling said in a review of The Crack-Up, “has remarked how innocent of mere ’sex,’ how charged with sentiment is Fitzgerald’s description of love in the jazz age”; the descriptions of love in Fitzgerald’s books are all descriptions of his own love.

Thus, his capacity for being hurt by Zelda was always very great. A month after the crisis he noted that they were “close together” again and in September that the “trouble [was] clearing away.” But long afterwards he wrote in his Notebooks: “That September 1924 I knew something had happened that could never be repaired.”

By some odd quirk Fitzgerald found that this crisis scarcely affected his ability to work. “It’s been a fair summer,” he wrote Max Perkins. “I’ve been unhappy but my work hasn’t suffered from it. I am grown at last.” That last sentence was one he was to repeat half hopefully and half ironically for the rest of his life. In August he had gone on the wagon and begun to get a great deal of good work done on his novel. Early in November he sent it off to Scribner’s, though he was anxiously revising almost up to the day of publication; he wasparticularly dissatisfied with chapters six and seven. “I can’t quite place Daisy’s reaction,” he wrote Perkins. As late as February 18, 1925, he cabled Perkins, hold up galley forty for big change. This change involved cutting five or six pages from the heart of the quarrel between Gatsby and Tom and rewriting the whole passage (The new material runs from ''I've got something to tell you, old sport' ...' (p. 156) to ''I just remembered that to-day's my birthday.'' (p. 163.) He had already done extensive rewriting on the proofs. The episode about 'Blocks' Biloxi (pp. 153-54), for example, was a last-minute inspiration, and he rewrote the last half of chapter six (from 'Tom was evidently perturbed...' on p. 125) at this time and relocated most of the material about Gatsby's past).

Meanwhile Zelda had been reading Roderick Hudson and as a result they decided to spend the winter in Rome. Fitzgerald wrote a Post story as quickly as he could after dispatching the novel, in order to provide ready money, and they got away about the middle of the month. It was not a happy winter. Fitzgerald was in a state of tension after three months of hard work on his novel and there were unresolved difficulties in their relation left over from the previous summer. It was not until after Christmas, widen Fitzgerald went on the wagon, that they were at peace again. “Zelda and I,” Fitzgerald wrote John Bishop, “sometimes indulge in terrible four day rows that always start with a drinking party but we’re still enormously in love and about the only truly happily married people I know.” They clung hard to this conviction and made it true for themselves.

They spent much of their time with the film company which was in Italy making Ben Hur in what they remembered as “bigger and grander papier-maché arenas than the real ones.” They made a good friend of Carmel Myers, who was staring in the picture, and years later she helped Fitzgerald with one of his many protégés in Hollywood. From this time forward the movies fascinated Fitzgerald. Later he was to say, “I saw that novel… was becoming subordinated to a mechanical… art. … I had a hunch that the talkies would make even the best selling novelist as archaic as silent pictures.” That “best selling” is an important part of the complex which made the movies fascinating to him: even in 1923 he had got almost as much for the movie rights to This Side of Paradise as he had made from The Beautiful and Damned as a book. But the movies fascinated him too, as they must fascinate any artist, because, as a visual dramatic art, they have such exciting possibilities of greatness, for all their actual shoddiness, and because they offered Fitzgerald what always drew him, a Diamond-as-Big-as-the-Ritz scale of operation, a world “bigger and grander” than the ordinary world.

But they hated Rome. They were always cold and they never could habituate themselves to the petty thievery which they found was a standard part of all relations with landlords, waiters, and taxi drivers in Italy. Once they were ordered from their table in a hotel to make room for some Roman aristocrat, and Fitzgerald never forgot his rage, as is shown by a note, apparently written about 1929 for his Notebooks but never included: “I’ve lain awake whole nights practicing murders. After I—after a thing that happened to me in Rome I used to imagine whole auditoriums filled with the flower of Italy, and me with a machine gun concealed on the stage. All ready. Curtain up. Tap-tap-tap-tap-tap.”

At one point Fitzgerald, in drunken exasperation, got in a fight with a group of taxi drivers when, at a late hour, they refused to take him to his hotel except for an extravagant fare. After one of his few successful blows struck a plain-clothes policeman who tried to interfere, Fitzgerald was hauled roughly off to jail. Zelda and a friend were able to rescue him only with some difficulty and a considerable distribution of largesse. The beating had been a severe one and Fitzgerald suffered from it physically for some rime. But its effect on his pride and conscience was even more important. His immediate motives, he knew, had been good: the taxi drivers had been extortionate and insulting; if he had lost control of himself, he had had some reason, and his first impulse was to assert indignantly his outraged innocence. But gradually, as he thought about the experience, he came more and more to blame himself; what had happened to him that he got into drunken brawls with taxi drivers? Thus bit by bit the humiliation of this experience came to seem to him a measure of his own deterioration, and he made out of the episode a symbol. Ten years later he spoke of it as “just about the rottenest thing that ever happened in my life” and by retelling it with a careful but persistent emphasis on his drunken loss of control he made it one of the most revealing instances of Dick Diver’s deterioration in Tender Is the Night. His deepest feelings about the experience are even more clearly revealed by the fact that this episode originally constituted the opening chapter of Our Type, where it was intended to give dramatic emphasis to Francis Melarky’s outbursts of murderous rage, a quality of character on which the whole novel was to turn. A humorous account of the actual experience is given in an essay-called The High Cost of Macaroni, that describes their winter in Rome and was intended as a third installment of the Post series that begins with How to Live on $36,000 a Year; the Post rejected it. The Dick Diver episode is in TENDER IS THE NIGHT Chapters XXII and XXIII.

In January both Fitzgeralds were sick and they decided to go to Capri to recover. Scott merely had grippe and was soon better but Zelda had a painful attack of colitis which she could not shake off. She was, with periods of temporary improvement, ill for a full year with it. It was while they were at Capri that Zelda began to paint, an interest which endured, with one long interruption for her ballet work, for the rest of her life. Fitzgerald met Compton Mackenzie, whose Sinister Street had meant so much to him ten years earlier, and liked him, though he no longer admired Mackenzie’s work. “I asked him,” Fitzgerald told Edmund Wilson later, “why he had petered out and never written anything that was any good since Sinister Street and those early novels.” The question is very much in character; poor Mackenzie could only reply that it was not true, as, indeed, it was not.

Fitzgerald himself was full of optimistic talk about starting a new novel, especially to Perkins, whom he always imagined he deceived more than he did about his periods of idleness; he did almost nothing during this spring except to worry about Zelda’s illness and about the reception of Gatsby and, in his anxiety, to drink more heavily than, as he knew, he should. One of his wonderfully funny letters written to Bishop from Capri concludes: “I am quite drunk again and enclose apostage stamp.” He was behind financially, as he always was after a spell of working on a book; he had borrowed to the limit against the expected royalties on Gatsby and owed Reynolds three stories, only one of which he actually got written during the spring.

The reception of his novel worried him most; he had committed all his forces in it and he realized that he was now old enough to be judged without qualification for his youth. His desire to put his talent to some serious use had flared up strongly after his experience of the previous winter and he had made a supreme effort with Gatsby. It was for him a test case of whether, in spite of his popularity and the critics’ hesitations about his earlier work, he could develop into a good novelist. As he waited, therefore, for its publication he became more and more nervous, not simply over whether it would be a financial success—he always had to worry about that—but over whether it would be considered good by the people whose judgments he respected.

Write me—he said to Bishop—the opinion you may be pleased to form of my chef d’oevre and others opinion. Please! I think its great. … Is Lewis’ book any good. I imagine that mine is infinitely better—what else is well-reviewed this spring? Maybe my book is rotten but I don’t think so.

There were remarks like this in nearly every letter he wrote, and beneath the joking there was more and more anxiety as publication date approached. Just before Gatsby was to appear—publication date was April 10—they decided to return to Paris, driving north from Marseilles in their car (the car, as usual, broke down, at Lyons, and they went the rest of the way by train). April 10 caught them in the south of France and Fitzgerald, his anxiety now beyond all reason, cabled Perkins on April 11, less than twenty-four hours after publication, ANY NEWS.

Next chapter 9

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).