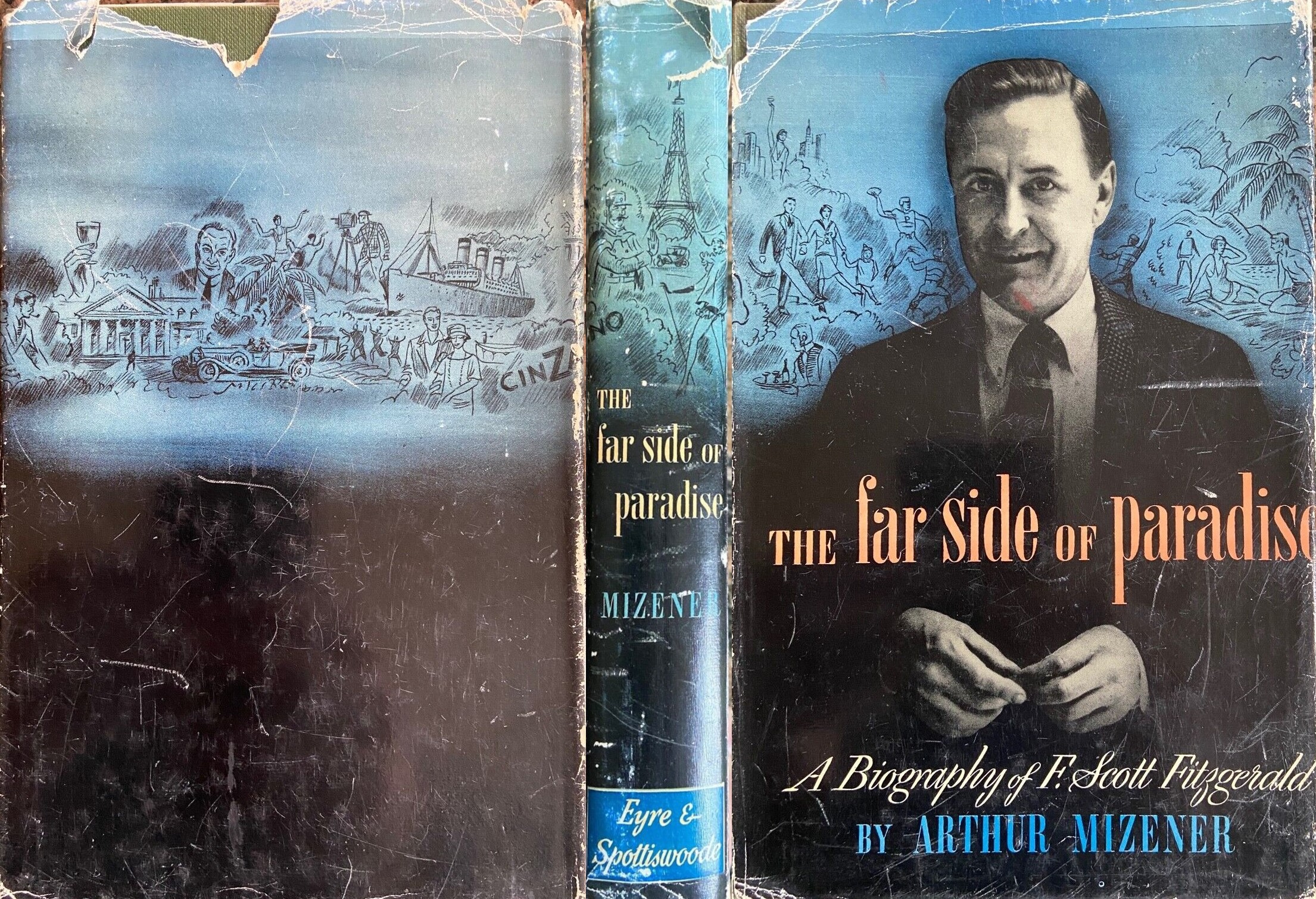

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter VII

In his genuine distress at finding himself sixteen hundred dollars in debt, Fitzgerald determined to work very hard; he planned to write a novel and a play within the next nine months. Before this new dedication to work could take effect, however, they decided, during the summer of 1920, to drive to Montgomery in their unreliable second-hand Marmon. Between mechanical disasters, bad hotels, and the natives’ responses to their matching linen knickerbocker suits, they had enough trouble on the trip to make an hilarious three-part article when Fitzgerald came to write it up. Parties in Montgomery delayed them, but by the middle of August they were back in Westport and Fitzgerald was started on his new novel. He was full of optimism about it and, having sold the serial rights to The Metropolitan for seven thousand dollars, he assured Perkins it would be ready for serialization by the middle of September and available for book publication in the spring. “Scott’s hot in the midst of a new novel,” Zelda wrote, “and West Port is unendurably dull,” but as Fitzgerald told Perkins, “the duller Westport becomes, the more work I do.”

By November, however, they were finding that “late autumn made the country dreary” and moved into an apartment at 38 West 59th Street. Through the fall Fitzgerald alternated parties with spurts of strenuous work on the novel. (“Done 15,000 words in last three days which is very fast writing evenfor me who write very fast,” he told Perkins.) By January enough hard work—and it took a great deal—had been done so that Part I of The Beautiful and Damned had been finished; a month later Wilson was reading and criticizing Part II and Fitzgerald was hoping to have the rest completed by the end of the month. Actually the book was not finished until just before they sailed for Europe at the beginning of May.

In March Zelda had discovered she was pregnant, which meant that if they were to take the trip to Europe which they had planned they would have to do so quickly, and amid a good deal of confusion they managed to get away on May 3 on the Aquitania. They began the trip with enthusiasm, Fitzgerald going carefully through the first-class passenger list and marking the names of all the important people, including “Mr. Francis S. Fitzgerald” (“Disguise! Sh!” he noted), but they quickly became depressed. They landed in England and then went on almost immediately to France, which was, Fitzgerald wrote Leslie, “a bore and a dissapointment, chiefly, I imagine, because we know no one here.” They sat for an hour outside Anatole France’s house hoping he would go in or out, but he did not oblige them. They went on to Florence and Rome, where they were similarly disappointed, and by the end of June they were back in London. There they dined with Galsworthy and, as he reported to Edmund Wilson, Fitzgerald said to him: “Mr. Galsworthy, you are one of the three living writers that I admire most in the world: you and Joseph Conrad and Anatole France!” When Wilson asked Fitzgerald what Galsworthy had said to that, Fitzgerald said: “I don’t think he liked it much. He knew he wasn’t that good.” But if that second observation represents accurately Fitzgerald’s cool, professional judgment of Galsworthy, there is a kind of truth in his first remark, too, the truth of his great admiration for writers and his desire to express it dramatically, with some sort of emotional truth. An even more extravagant display of this second impulse occurred when he met Joyce inParis. Addressing Joyce as “Sir” he asked him if he were not very proud of his achievement. Then he announced that, to show his abasement before Joyce’s genius, he was going to jump out of the window. Joyce prevented the paying of this tribute and said afterwards in obvious puzzlement: “That young man must be mad—I’m afraid he’ll do himself some injury.” (This story comes from Edmund Wilson, who had it from Herbert Gorman.)

Fitzgerald had begun his visit in England by announcing that he planned to settle there; then, after ten days in London, decided from one day to the next to go home. He called Charles Kingsley, Scribner’s London representative, at seven-thirty one morning to say he needed money; one hour later he was on Kingsley’s doorstep in Richmond where he announced that he had had a rotten time, clutched the twenty pounds Kingsley had managed to scrape together for him, and shot off in a cab to catch the nine-thirty train for Liverpool. Not even Edmund Wilson’s appeal from Paris—“Cancel your passage and come to Paris for the summer!”—could stop them. “What an overestimated place Europe is!” Fitzgerald concluded. Zelda summed up the whole phantasmagoric period from their marriage to their return from Europe in her exuberant and ungrammatical prose: “Lustily splashing their dreams in the dark pool of gratification, their fifty thousand dollars bought a cardboard baby-nurse for Bonnie, a secondhand Marmon, a Picasso etching, a white satin dress … a yellow chiffon dress … a dress as green as fresh wet paint, two white knickerbocker suits exactly alike, a broker’s suit: … and two first-class tickets for Europe.”

By the end of July they were back in Montgomery considering the possibility of taking a house there, for they were determined to get away from New York and the parties, at least until their child was born. But eventually Scott’s home town won out, and in the middle of August they arrived in St. Paul, where Scott’s old friend Sandra Kalman had rented them a house at Delwood for the summer. It was a triumphant return for the young man who had left eight months before with just enough money to keep him going in New Orleans. Between the continued popularity of This Side of Paradise and the first serial rights of The Beautiful and Damned he was making more money than ever. Moreover he was a famous man. He and Zelda were paragraphed in the papers when they arrived and Fitzgerald was quoted as saying that he “had got tired of New York and had decided to come to a nice quiet town to write.” He also informed the press that he had three novels mapped out in his mind and that he would run off a dozen stories for a weekly magazine, presumably the Post, before he tackled them. The papers referred to him as “St. Paul’s first successful novelist” and he was obviously doing his best to look the part. He even addressed the Woman’s Club of St. Paul, informing them that he was the inventor of bobbed knees. “And all the while,” as one sympathetic observer remarked, “he is a somewhat wistful, very sensitive, impulsive and attractive young man, not half as spoiled as it would be reasonable to expect.”

It was a brave show, and publicly Fitzgerald did his best to make it appear that they had their lives under control; privately, however, he was discouraged about the way they were living and its effect on his work. Out of one of those states of depression in which he was inclined to exaggerate the disorder of their lives, he wrote Perkins: “I’m having a hell of a time because I’ve loafed for 5 months and I want to get to work. Loafing puts me in this particularly obnoxious and abominable gloom. My 3rd novel, if I ever write another, will I am sure be black as death with gloom. I should like to sit down with ½ a dozen chosen companions and drink myself to death but I am sick alike of life, liquor and literature. If it wasn’t for Zelda I think I’d disappear out of sight for three years. Ship as a sailor or something and get hard—I’m sick of the flabby semi-intellectual softness in which I flounder with my generation.” For the moment the man who wantedto achieve had the upper hand of the man who wanted to enjoy. As a result he got through an enormous amount of work that fall and winter. He had hired an office downtown, a bare affair with nothing but a desk and two chairs; its location was known only to a few of his most intimate friends. Here he went daily to work. He got The Beautiful and Damned ready for book publication in March, he produced two very long short stories—“The Popular Girl” and “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz”—and he completed the first draft of the play which was to occupy him more and more for the next two years.

Nor was their personal life unhappy, for all the gloom of Fitzgerald’s letter to Perkins. He and Zelda were happy together and there were long summer days of consultations over his work, to which Zelda made very real contributions; they golfed and swam and dined with the Kalmans. Their talent for giving excitement and charm to an occasion made it a gay time. Fitzgerald planned and carried off by his enthusiasm all sorts of jokes. On the occasion of the Cotillion in January, for instance, he wrote a parody society-page description of the party and had it printed up as a newspaper. cotillion is a sad failure, said the headline, and the subhead, frightful orgy at university club. “The benedict’s cotillion given Friday the 13th,” said the description, “was the worst social failure of the year. In a sordid fist fight started by Mr. William Motter four noses were broken and one removable bridge was bent out of recognition. The fight was said to have started because some remark derogatory to Yale was made before Mr. Motter [Mr. Motter had gone to Princeton]…. It is to be hoped that these vain frivolous peacocks who strut through the gorgeous vistas of the exclusive and corrupt St. Paul clubs will learn to conduct themselves in a more normal, wholesome way.”

As always, the people who really knew Fitzgerald felt most his infectious enthusiasm and the charm of his childlike curiosity and love of play-acting. His friend Tom Boyd described how Fitzgerald saw a blind man tapping along the street and immediately wanted to know what it felt like to be blind. He closed his eyes and began to tap his way along the street too. “He had almost experienced the sensations of a blind man for an entire block on a crowded street when unluckily, two middle aged women passed us by and passing, one said to the other: ‘Oh look at that.’ And Fitzgerald opened his eyes.” When he discovered they were speaking, not about him, but about a bargain in a store window he was furious. He insisted, however, that he had walked as well as the blind man and was indignant when Boyd denied it firmly and said that in fact he walked like a man with the blind staggers. But a minute later something else caught his fancy and he was once more cheerful and enthusiastic. His childhood friend, Tubby Washington, remembers with similar amusement how he went one day to Fitzgerald’s office to borrow fifty dollars from him for the most innocent of purposes, only to encounter Fitzgerald The Man of the World. “Well, well, Tubby,” he said, leaning back in his chair, “now what’s this all about? Got some girl knocked up in Chicago, eh?” When Tubby insisted the matter was nothing so conventionally melodramatic as that, Fitzgerald began by assuring him he could not lend the money and ended by talking himself around to lending forty-nine dollars, the odd dollar being a fairly accurate measure of Fitzgerald’s respect for the mythology of laissez-faire. (Fitzgerald, like most people who have known poverty, had too vivid a memory of what a few dollars can mean ever to put up much resistance to a borrower. Compare 'Hot and Cold Blood.') He loved nothing better than to expose this mythology. Tubby had, earlier, gone to apply for a job which his father had got for him by pulling wires and then had been forced to listen to a long harangue about the firm’s “always having a place for bright young men, etc. “; he hurried home to share this choice absurdity with Fitzgerald. They roared over it together, and Fitzgerald presently wrote a story about it called “Dalyrimple Goes Wrong.”

Tom Boyd and his wife, Peggy, and Cornelius Van Nessand one or two others formed a congenial literary group around the Kilmarnock Book Shop at Fourth and Minnesota, and Fitzgerald spent long hours there arguing and drinking with them. When Joseph Hergesheimer, then at the peak of his fame, came through in January to dazzle St. Paul with his coonskin coat, shell-rimmed spectacles, and cane, it was this group which entertained him.

In October the Fitzgeralds moved back to the city, first to a hotel and then, after their daughter was born on October 26, to a house at 646 Goodrich Avenue which Mrs. Kalman again found for them. Discovering at the last moment that in their casual way they had made no arrangements whatever for the baby, Mrs. Kalman also found herself purchasing supplies and providing a nurse for the baby. It was she, too, who supported an incredibly nervous father through the ordeal of waiting at the hospital. In his excitement at the baby’s birth Fitzgerald sent telegrams broadcast announcing that a second Mary Pickford had arrived. His New York friends wired back: CONGRATULATIONS FEARED TWINS HAVE YOU BOBBED HER HAIR and Mencken advised that they NAME HER CHARLOTTE AFTER CHARLES EVANS HUGHES.

But if the Fitzgeralds were usually happy and attractive they were also occasionally unhappy and difficult. They disliked St. Paul, particularly in winter. “We are both simply mad to get back to New York,” Zelda wrote. “… This damned place is 18 below zero and I go around thanking God that, anatomically and proverbially speaking, I am safe from the awful fate of the monkey.” Zelda revenged herself on St. Paul by offending against its mores. She stood on the back platforms of trolleys smoking, and made a business of shocking the young men who danced with her (“My hips are going wild; you don’t mind, do you?”). At the movies she commented loudly. “I think Gilda Gray is the most beautiful girl in the world, don’t you? If I were a man I’d give a year of my life to live with her a week. She has rather thick ankles, don’tyou think? I wouldn’t give five minutes to live with her a week if I were a man.”

After the baby was born and Zelda was tied down, St. Paul became exasperatingly dull. Fitzgerald’s impulse was to have more parties, and he used to fall into embarrassing public arguments with Zelda about inviting people to the house. “You won’t come, will you?” Zelda would say to people Fitzgerald had invited to come for a drink. “The baby wakes up and yells and the place is too small. We don’t want you.” Then Scott would draw them aside to say confidentially: “Zelda’s got this silly notion that we can’t have anyone in the place; she ought to have it knocked out of her head; you’ll come up, won’t you, and help me cure her of this idea.” Back of it all somewhere was the ceaseless battle of the mind; one of Fitzgerald’s St. Paul acquaintances remembers overhearing him muttering to himself as they drove past a church one night: “God damn the Catholic Church; God damn the Church; God damn God.”

In February Fitzgerald was down with flu and beginning to work himself into his customary pre-publication frame of mind.

My deadly fear now is—he wrote the long-suffering Perkins—not the critics but the public. Will they buy—will you and the bookstores be stuck with forty thousand copies on your hands? Have you overestimated my public and will this sell up to within seven thousand of what Paradise has done in two years? My God! Suppose it fell flat!

On March 3 The Beautiful and Damned was published.

It is, compared to This Side of Paradise, a painstakingly thought-out book, and for that reason a much less effective one; its real purpose is constantly being obscured by its “literary” purpose, Fitzgerald’s conscious effort to be ironic and superior in the fashionable manner of George Jean Nathan (on whom he drew heavily for Maury Noble). What Fitzgeraldthe literary man believed he was doing is quite clear from the blurb on the dust jacket (in which he almost certainly had a hand). “… it reveals with devastating satire a section of American society which has been recognized as an entity—that wealthy, floating population which throngs the restaurants, cabarets, theatres, and hotels of our great cities”—a description that fits the famous chapter about the floating newly rich in Wells’ Tono-Bungay far better than it fits The Beautiful and Damned. But this intention is at odds with the real story Fitzgerald had to tell, the story of what he had known and felt in the incredible years since the success of This Side of Paradise. The consequences of these mixed purposes were clear to the best of the reviewers. “… Mr. Fitzgerald,” said Mary Colum, “has not the faculty [needed by a satirist] of standing away from his principal characters”; and Carl van Doren said that “what hurts ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ is deliberate seriousness—or rather, seriousness not deliberated quite enough…. Fitzgerald has trusted … his doctrine rather more than his gusto.” “‘The Beautiful and Damned,’” said H. W. Boynton, “is a real story, but a story greatly damaged by wit… the bane, not the making, of a true storyteller.”

The result of this mixture is a confusion of the novel’s purpose, and this confusion is increased by Fitzgerald’s disregard for form. In this last respect he had learned a good deal since This Side of Paradise, but he still seemed to think there was some special virtue in passages written in play form; there are three of these, including an embarrassing scene in the manner of Man and Superman between Beauty and The Voice. He also allowed himself to go haring off in any direction which promised a little smart satire or talk about the meaninglessness of it all. Gloria’s entrance is delayed in order that he may do a satiric portrait of her parents, who never appear again; Gloria is made to evince a most implausible fellow feeling for the lower-middle classes in order that the rabblewho patronize second-rate cabarets may be looked down on at length; Anthony, the least likely of all people to do so, answers an ad for salesmen in order that go-getters may be satirized. The book also contains a great deal of witty cynical dialogue and lecturing on Life.

M a u r y : … I shall go on shining as a brilliantly meaningless figure in a meaningless world.

D i c k : (pompously) Art isn’t meaningless.

M a u r y : It is in itself. It isn’t in that it tries to make life less so …

A n t h o n y : (to Maury) On the contrary, I’d feel that it being a meaningless world, why write? The very attempt to give it purpose is purposeless.

Perhaps the worst offense of this kind is the long harangue delivered by Maury Noble from the roof of the Marietta station, a passage of which The Dial’s reviewer observed that it sounds “like a résumé of The Education of Henry Adams filtered through a particularly thick page of The Smart Set.”

Some of these things Fitzgerald half suspected. “If you think my ‘Flash Back in Paradise’ in Chap I is like the elevated moments of D. W. Griffith say so,” he wrote Bishop of the scene between Beauty and The Voice. And to Wilson, who had criticized severely the ideas in the original version of Maury Noble’s speech, he said, “I’ve almost completely rewritten my book…. I’ve interpolated [in the Symposium scene] some recent ideas of my own and (possibly) of others.” At the same time he could say: “I devoted so much more care myself to the detail of the book than I did to thinking out the general scheme…”

The worst effect of this mixed purpose was the way it muddled the characters of Anthony and Gloria. Fitzgerald never made up his mind whether he wanted to stand apart from them and treat them satirically or to enter into their experiencewith sympathy and understanding. “As you first see him,” the fashionable satirist says of Anthony, “he wonders frequently whether he is not without honor and slightly mad… these occasions being varied, of course, with those in which he thinks himself rather an exceptional young man, thoroughly sophisticated….” But when he comes to describe the courtship and honeymoon of Gloria and Anthony, this cool, man-of-the-world air deserts him and he is carried away by the poignancy and delight of their love. About this muddle his friend Edmund Wilson was very severe: “… since his advent into the literary world, [Fitzgerald] has discovered that there is another genre in favor: the kind which makes much of the tragedy and ‘the meaninglessness of life.’ Hitherto, he had supposed that the thing to do was to discover a meaning in life; but he now set bravely about to produce a distressing tragedy which should be, also, 100 per cent. meaningless.”

But this description is not fair to The Beautiful and Damned, for there is more than the fashionable Fitzgerald in it; there is also the novel he would have written straight had he not made his advent into the literary world. About this novel there are still some of the defects of This Side of Paradise. There is still for example, the curious shocked immaturity about sex: Anthony’s prep-school philandering with Géraldine and the lovers who push about menus on which they have written “you know I do” and describe each other as “sort of blowy clean,” Gloria’s smart dictum that “a woman should be able to kiss a man beautifully and romantically without any desire to be either his wife or his mistress.” Like the lovers of This Side of Paradise, these lovers are embarrassingly real (they are real; Fitzgerald and Zelda said these things to one another).

Nonetheless, The Beautiful and Damned has a central purpose and meaning. Fitzgerald got into it his acute sense of disaster and his ability to realize the minutiae of humiliation and suffering. “It is,” as William Troy put it, “not so much astudy in failure as in the atmosphere of failure.” It would be difficult, for example, to match the scene in which Anthony, penniless and drunk, tries to borrow money from Maury Noble and Bloeckman. Fitzgerald’s difficulty is in finding a cause for this suffering sufficient to justify the importance he asks us to give it and characters of sufficient dignity to make their suffering and defeat tragic rather than merely pathetic. It is not that he did not try; amid the confusion of other purposes there is a fairly consistent effort to make Anthony the sensitive and intelligent man who, deprived of a conventional career by his refusal to compromise with a brutal and stupid world, finds his weaknesses too strong to allow him the special career he imagines for himself. He is tempted to cowardice by his imagination; he cannot blame others for his failures and fight them because of “that old quality of understanding too well to blame—that quality which was the best of him and had worked swiftly and ceaselessly toward his ruin.” Over against Anthony, Fitzgerald sets Richard Carmel, too stupid to know he is compromising or to see that the success he has won by compromising is not worth having, and Maury Noble, cynical enough to compromise even though he knows the worthlessness of what he gets.

The trouble with this story is that Anthony is not convincing as the intelligent and sensitive man; what is convincing is the Anthony who is weak, drifting, and full of self-pity—perhaps because Fitzgerald was exaggeratedly aware of these qualities in himself. You are convinced by the Anthony who drifts into the affair with Dorothy Raycroft under a momentary flicker of his romantic imagination, though he knows perfectly well that he does not believe in the affair; you are convinced by the Anthony who is continually drunk because only thus can he sustain “the old illusion that truth and beauty [are] in some way intertwined”; you are convinced by the partly intolerable, partly absurd, partly pathetic Anthonywho tries to sustain his dignity and honor even after he has deteriorated—against Maury who tells him to sober up, against Bloeckman who has unintentionally humiliated Gloria, against Gloria herself. This Anthony is fully realized. But the thing that would justify this pathos, the quality of character which would make Anthony a man more sinned against than sinning, is almost wholly lacking. In her way Gloria is a more successful character in spite of the gap between what she is at the beginning of the book and what she is at the end. What she believes in—the rights and privileges of her beauty—is more trivial even than what Anthony believes in—the rights and privileges of his own undemonstrated intellectual superiority. But she believes in it with courage, and when she is forced, in brutal circumstances, to recognize it is fading, she takes her defeat with something like dignity.

The story of Gloria and Anthony is full of precisely observed life, and Fitzgerald makes us feel the grief they suffer; but he is able to provide neither an adequate cause for their suffering nor adequate grounds in their characters for the importance he gives it. In the end you do not believe they ever were people capable of using well the opportunities for grace and mobility that wealth provides; you believe them only people who wanted luxury and stimulation. They are pitiful, and their pathos is often overwelmingly convincing; but they are not tragic and damned as Fitzgerald meant them to be. At the time he wrote The Beautiful and Damned he had mastered the quality but not the reason of his moral judgment of his experience; had he not muddied his book with smartness, he might, even at this stage in his career, have written a definitive novel of sentiment. His attempt to make The Beautiful and Damned a kind of American Madame Bovary defeated him; he could not yet, as he could when he got to The Great Gatsby, separate his sympathy from his judgment, because he could not really define his judgment.

Next chapter 8

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).