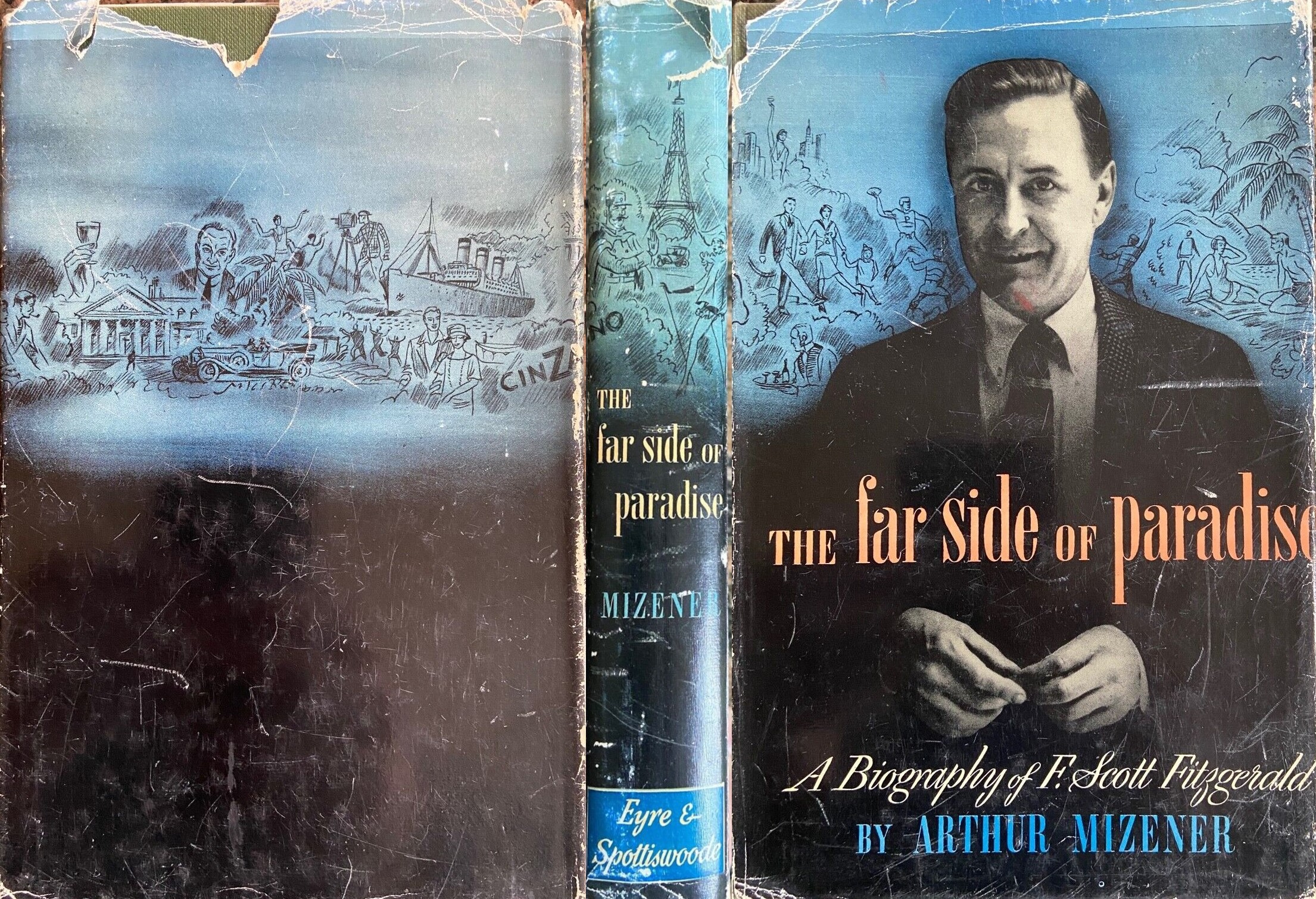

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter VI

At the middle of this whirl of parties stood the Fitzgeralds. The boy from Minnesota who, as he said himself, “knew less of New York than any reporter of six months standing and less of its society than any hall-room boy in a Ritz stag line,” and his girl from Montgomery, Alabama, were an immediate and brilliant success in New York. With the publication of This Side of Paradise Fitzgerald had become a hero to his generation. To the young people who found in the book a glorious expression and a justification of the life they believed in and longed for, he became, as Glenway Wescott put it, “a kind of king of our American youth.” For this role he appeared to be almost ideally equipped. He was strikingly handsome, gracefully casual and informal; he loved popularity and responded to it with great charm; his strong sense of responsibility for the success of a social occasion made him exercise his Irish gift of gay nonsense until it seemed as if the fun he could invent was inexhaustible. He was in his own person a triumphant justification of the way of life he described in his book. So, too, was Zelda. In no way a professional beauty, or, like some Southern girls, consciously feminine, she had with her striking red-gold hair an “astonishing prettiness.” Like Amory Blaine’s Rosalind, she loved to be sunburned and healthy and fresh. As a young woman she used little make-up; her nails were, like a sensible child’s, clippedand unpolished. The combination of her unself-conscious and fresh young prettiness with the wit and unconventionality of her attitude was invariably fascinating. With her quick intelligence she immediately adjusted herself to the manners and customs of the New York world without losing the special attraction of her southernness and her independence; she was, as one of their friends put it, “a barbarian princess from the South.”

“The other evening at a dancing club,” one of their contemporaries wrote, “a young man in a gray suit, soft shirt, loosely tied scarf, shook his tousled yellow hair engagingly, introduced me to the beautiful lady with whom he was dancing and sat down. They were Mr. and Mrs. Scott Fitzgerald, and Scott seemed to have changed not one whit from the first time I met him at Princeton, when he was an eager undergraduate bent upon becoming a great author. He is still eager. He is still bent upon becoming a great author.” Ring Lardner was, therefore, expressing precisely the period’s feelings about the Fitzgeralds when, in his modernized versions of familiar fairy stories, he called the prince Scott and Cinderella Zelda,—

None had such promise then, and none

Your scapegrace wit or your disarming grace;

For you were bold as was Danaë’s son,

Conceived like Perseus in a dream of gold,

as John Peale Bishop wrote of Scott.

Like a fairy-story hero and heroine they lived in a world in which the important things were romance and thrills—both of which could be bought on a roof garden in New York if you just had enough money. The attitude comes through very clearly in “Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr—nce of W—les.” “So I go in with my purse full of beauty and money and youth,” says Rags, “all prepared to buy. ‘What have you gotfor sale?’ I ask [the merchant], and he rubs his hands together and says: ‘Well, Mademoiselle, to-day we have some perfectly be-oo-tiful love.’ Sometimes he hasn’t even got that in stock, but he sends out for it when he finds I have so much money to spend.” So the hero of the story, a bright young executive, gives Rags an evening at a roof garden where he fools her into thinking she has met the Prince of Wales and she thanks him for “the second greatest thrill” of her life and marries him. Thus wrote the romantic young man in Fitzgerald, who guided him during these wonderful months of triumph and success. What the spoiled priest was thinking of it all was another matter. A decade later he was to say in “Babylon Revisited” of the man who locked his wife out in the snow after a drunken quarrel: “… the snow of twenty-nine wasn’t real snow. If you didn’t want it to be snow you just paid some money.”

The Fitzgeralds went about New York spending money and “doing what they had always wanted to do” with a youthful innocence and gusto which made whatever they did seem a part of their charm. They were as likely to be two or three hours late to a dinner party as on time and even more likely not to come at all. They went to people’s houses, carefully greeted their hosts, and then sat down quietly in a corner and, like two children, went fast asleep (Town Topics, clipping in ZELDA SAYRE FITZGERALD's Scrapbook. As Hemingway points out in A Moveable Feast (p. 181), falling asleep this way protected them. ‘They went to sleep on drinking an amount of liquor or champagne that would have little effect on a person accustomed to drinking… and when they woke they would be fresh and happy, not having taken enough alcohol to damage their bodies before it made them unconscious.’). They rode down Fifth Avenue on the tops of taxis because it was hot or dove into the fountain at Union Square or tried to undress at the Scandals, or, in sheer delight at the splendor of New York, jumped, dead sober, into the Pulitzer fountain in front of the Plaza (Zelda dove into the fountain at Union Square; the event was later celebrated in the Greenwich Village Follies. Fitzgerald jumped into the Pulitzer fountain; his account of his motives for doing so is incorporated into Wilson's The Delegate from Great Neck from Discordant Encounters, p. 58. Fitzgerald's attempt to undress at the Scandals appears in THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, NEW YORK, 1922, p. 390). Fitzgerald got in fights with waiters and Zelda danced on people’s dinner tables (Fitzgerald refers to the fight in My Lost City—the fight occurred that summer of 1920 and was written up in The News—and Edmund Wilson described it in The Crime in the Whistler Room from Discordant Encounters, pp. 195-97.). “When Zelda Sayre and I were young,” said Fitzgerald, “the war was in the sky,” and with his incurable honesty he always remembered how optimistic and assured they all felt about life as they actually lived it in the early twenties “when we drank wood alcohol and every day in every way grew better and better, and there was afirst abortive shortening of the skirts, and girls all looked alike in sweater dresses, and people you didn’t want to know said ‘Yes, we have no bananas,’ and it seemed only a question of a few years before the older people would step aside and let the world be run by those who saw things as they were.” It was for them a time “when the fulfilled future and the wistful past were mingled in a single gorgeous moment.” Fitzgerald had achieved his dream of writing a famous book, marrying Zelda, and making a success in New York. For a moment the delights of anticipation remained a part of the achievement. At the same time Fitzgerald knew that fulfillment destroys the dream. In the middle of this achieved “orgiastic future,” as he calls it in The Great Gatsby, he sat alone one day, riding through New York “between very tall buildings under a mauve and rosy sky,” and “bawl[ed] because I had everything I wanted and knew I would never be so happy again.” It was not simply that the orgiastic future which “year by year recedes before us” drove him to “run faster, stretch out his arms farther” in a pursuit that he half understood was self-defeating even as he gave more and more of his time and energy to it; it was also that the man who wanted to “achieve … to be … wise, to be strong and self-controlled” always stood at the elbow of the man who wanted “to enjoy, to be prodigal and open-hearted … to miss nothing,” reminding the former that he was marking time, that he was not doing anything except waste his gift and strain his resources writing commercial stories under terrible pressure in order to pay for the party (The quoted phrases here are from The Great Gatsby, New York, 1925, p. 218 and the ms. of Our Type (the passage is quoted at length above). See also My Lost City).

Moreover, in spite of their success, they were often lonely and confused; “Within a few months after our embarkation on the Metropolitan venture we scarcely knew any more who we were and we hadn’t a notion what we were,” Fitzgerald said. This confusion was the result not simply of the social situation but also of themselves, or at least of Fitzgerald. He was not exactly a shy man so much as one who was neverwholly at his ease socially. For ease he substituted a kind of dramatic power on which he depended to charm and entertain people. He did not expect people to believe most of what he said; part of the fun was that it was not true. He delighted in such occasions as the one on which he hurried in half an hour late for an engagement at the Manhattan Bar and said, with anxious apology: “I’m very sorry I’m late. You see, I got run over by a bus.” When his friend said: “My God, Scott, are you all right,” he was heroically superior to the whole affair; “yes, yes”—brushing himself off casually—“I just picked myself up.” But it required energy and inventiveness to carry off this role constantly, especially as it was part of Fitzgerald’s very real generosity as well as of his pleasure in shining that he was always anxious to be entertaining. “Once,” as he wrote Max Perkins years later, “I believed in friendship, believed I could (if I didn’t always) make people happy and it was more fun than anything.” “It is in the thirties that we want friends,” he added in the Notebooks. “In the forties we know they won’t save us any more than love did.”

In the delight and confusion of this life, Fitzgerald’s old habit of falling into a mood of lofty assurance in which he innocently advised all comers for their own good and talked endlessly about himself reasserted itself. He was like Richard Carmel in The Beautiful and Damned, who, in this respect, is half a portrait and half a gloomy prediction—for Fitzgerald exaggerated his faults in this mood—of his creator’s future. (Richard Carmel actually wrote the novel called The Demon-Lover which Fitzgerald had projected a year before.)

The author, indeed, spent his days in a state of pleasant madness. The book was in his conversation three-fourths of the time—he wanted to know if one had heard “the latest”; he would go into a store and in a loud voice order books to be charged to him, in order to catch a chance morselof recognition from clerk or customer. He knew to a town in what sections of the country it was selling best; he knew exactly what he cleared on each edition, and when he met any one who had not read, or, as it happened only too often, had not heard of it, he succumbed to moody depression.

He read all the publicity about his being “the youngest writer for whom Scribner’s have ever published a novel” and was even persuaded to say that This Side of Paradise was “a novel about Flappers written for Philosophers.” Heywood Broun, better than any critic in New York, put his finger on this brash quality in both the book and Fitzgerald’s conduct, though he seems not to have felt its authentic charm:

We have just read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “This Side of Paradise” (Scribner’s)—he wrote—and it makes us feel very old. According to the announcement of his publishers Mr. Fitzgerald is only twenty-three, but there were times during our progress through the book when we suspected that this was an overstatement. Daisy Ashford is hardly more naive…. None of Fitzgerald’s characters ever puts his hands down for a second. There is too much footwork and too much feinting for anything solid and substantial being accomplished. You can’t expect to have blood drawn in any such exhibition as that.

“… for some days [after this attack],” Fitzgerald remembered, “I was notably poor company.” Nonetheless, he tried to meet Broun’s onslaught by inviting him to lunch and, as he himself put it later, “in a kindly way [telling] him that it was too bad he had let his life slide away without accomplishing anything. He had just turned thirty….” Broun’s response to this well-meant advice was to print one of Fitzgerald’s interviews in which he told how he had become a great writer, and to remark at the end of it: “Having heard Mr. Fitzgerald, we are not entirely minded to abandon our notion that he isa rather complacent, somewhat pretentious and altogether self-conscious young man.” (Richard Carmel also gave this interview, THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, NEW YORK, 1922, pp. 188-89. Fitzgerald answered Broun two years later when he reviewed Broun's novel, The Boy Grew Older, for the St. Paul Daily News. '[Broun's] literary taste,' he said, '…is pretty likely to be ill-considered, faintly philistine and often downright absurd.'—Clipping in Album III.) Fitzgerald was not consoled by Perkins’ tactful suggestion that “we consider all this sort of thing as advantageous.” The boy who, full of dreams of the glories of prep-school life and of his own heroic role in it, had quickly made a bad name for himself at St. Paul Academy and Newman had reappeared; no one had yet found a means to shut Scotty’s mouth. So amused were Bishop and Wilson by this sudden excess of greatness that they sent Fitzgerald a list of items for a “Proposed exhibit of Fitzgeraldiania for Chas. Scribner’s Sons.” It included “Three double malted milks from Joe’s [a popular undergraduate eating place in Princeton]… Overseas cap never worn overseas… 1 bottle of Oleaqua [a much publicized hair tonic sold by Jack Honoré’s barber shop in Princeton]… Entire Fitzgerald library consisting of seven books, one of them a notebook and two made up of press clippings… First yellow silk shirt worn by Fitzgerald at the beginning of his great success… Mirror.”

In May he and Zelda decided to achieve peace and to collect their souls in the country; they began investigating Westchester County and near-by Connecticut. They needed a car, and “a man sold [them]”—the phrase is eloquent of what happened—a second-hand Marmon. Zelda did not improve the car when she “drove it over a fire-plug and completely deintestined it.” “About once every five years,” as Fitzgerald said, “some of the manufacturers put out a Rolling Junk, and their salesmen come immediately to us because they know that we are the sort of people to whom Rolling Junks should be sold.” Eventually they settled in Westport in a comfortable gray-shingled house known locally as, the Burritt Wakeman place.

But peace did not descend; instead weekend guests descended. One night, out of some kind of boredom, Zelda put in a fire alarm and when the department arrived and askedwhere the fire was, she struck her breast dramatically and said, “Here.” The gesture is sometimes ascribed to Fitzgerald (e.g., Thomas Boyd, 'Literary Libels, II,' the St. Paul Daily News, March 7, 1922). The local paper reported with ill-concealed anger that when 'the chief and his assistants… went to the Fitzgerald house… investigation proved of little use, everyone of the occupants claiming they knew nothing about the alarm. Some member of the family suggested that possibly someone came into their house during their absence and sent in an alarm.' 'There is a statute,' the local reporter concludes, 'which deals severely with people who send in false alarms for the fun of it.' When Fitzgerald was brought before the prosecutor the next week he said 'that he did not feel he was to blame for the alarm being sent in but that he would take the responsibility and bear the costs of the department making the run.' The newspaper clippings about this affair are in ZELDA SAYRE FITZGERALD's Scrapbook. “There were people in automobiles all along the Boston Post Road,” Zelda said afterwards, “thinking everything was going to be all right while they got drunk and ran into fire-plugs and trucks and old stone walls. Policemen were too busy thinking everything was going to be all right to arrest them.” Through May and June they saw a host of old and new friends, college friends of Scott’s like John Biggs and Townsend Martin, new acquaintances like Charles Towne. George Jean Nathan came for a weekend and immediately announced that their Japanese servant, Tana, had whispered to him that his real name was Lieutenant Emile Tannenbaum and that he was a German Intelligence Officer; he kept urging on them parties which were hard to resist; “Can’t we all have a party during the week? Mencken will be here and I should like to have you meet him. I have laid in three more cases of gin,” he would write. He flirted gaily with Zelda. But for all his high spirits, he aroused Fitzgerald’s jealousy and Fitzgerald picked a quarrel with him. Though they were very much in love, both Fitzgeralds were, in their different ways, easily made jealous. Scott’s was a lover’s jealousy, and when it was aroused, all the old-fashioned morality of his upbringing, which was not very far below the surface of his nature at any time, came out. Zelda, on the other hand, was often unhappy when Scott was lionized, for she liked to be the center of things as much as he did. “They love[d] each other… desperately, passionately. They [clung] to each other like barnacles cling to rocks, but they want[ed] to hurt each other all the time…” says Simone of David and Rilda (who are contemporary portraits of the Fitzgeralds) in Van Vechten’s Parties. This was the impression they gave people.

Gradually the division in Fitzgerald’s nature was being reinforced by the life they were living, by Zelda’s delight in it and her appeal to the old feeling, left over from his wooing, that her love required it.

When I was your age—he wrote his daughter in 1938—I lived with a great dream. The dream grew and I learned how to speak of it and to make people listen. Then the dream divided one day when I decided to marry your mother after all, even though I knew she was spoiled and meant no good to me. I was sorry immediately I had married her, but being patient in those days, made the best of it and got to love her in another way. You came along and for a long time we made quite a lot of happiness out of our lives. But I was a man divided—she wanted me to work too much for her and not enough for my dream.

This account of his feelings is distorted by the opinions of the much older Fitzgerald who wrote it. What he said about the Anthony and Gloria of The Beautiful and Damned in 1921 is probably closer to what he felt at the time. “The idyl passed,” he said of them. “… But, knowing they had had the best of love, they clung to what remained. Love lingered—by way of long conversations at night … by way of deep and intimate kindnesses they developed toward each -other, by way of their laughing at the same absurdities and thinking the same things noble and the same things sad.” But those who worried about Fitzgerald’s career worried about his working for Zelda, and the spoiled priest in Fitzgerald did too. “Scott was extravagant,” said Max Perkins, “but not like her; money went through her fingers like water; she wanted everything; she kept him writing for the magazines.” (Mr. Turnbull quotes some fascinating observations of the kind of pressure Zelda was putting on Fitzgerald at this time from the diary of Fitzgerald's college friend Alec McKaig, who was seeing a great deal of them during these months. For example: 'Spent evening at Fitzgeralds. Fitz has been on wagon 8 days - talks as if it were a century. Zelda increasingly restless - says frankly she simply wants to be amused and is only good for useless, pleasure-giving pursuits; great problem - what is she to do?'—Scott Fitzgerald, p. 114.)

All this Fitzgerald understood better than he has sometimes been given credit for, but he was, as he said in his Notebooks, “too many people” to act wholly on the judgment of any one of them. One night about this time, in a speakeasy, he struck up a casual acquaintance with James Drawbell and the two of them went off to Drawbell’s “small back airless room on the top floor [of a] grubby brownstone house” to talk. “Don’t be stuffy,” Fitzgerald said when Drawbell apologized for theroom. “You’re not the only one. I put up at a dreadful hole once.” “Parties,” he then said, thinking of the one he had just walked out on, “are a form of suicide. I love them, but the old Catholic in me secretly disapproves. I was going to the world’s lushest party tonight.” A moment later he was saying, “Nice to get away from the gang and meet another bewildered and despairing human soul,” and when Drawbell said, “Bewildered, yes….” Fitzgerald added, “The rest will come. Wait till you’re successful.”

Gradually, however, in the midst of all this bewilderment, Fitzgerald’s writer’s conscience, his serious ambition, began to assert itself; what that conscience thought of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald was to come out in his portrait of Anthony and Gloria, Patch in his next novel. “My new novel,” he wrote Mr. Scribner a little later, “called ‘The Flight of the Rocket’ concerns the life of Anthony Patch between his 25th and 33rd years (1913-1921). He is one of those many with the tastes and weaknesses of an artist but with no actual creative inspiration. How he and his beautiful young wife are wrecked on the shoals of dissipation is told in the story.” This description points up the share which Fitzgerald’s feelings about himself and Zelda played in The Beautiful and Damned. If you were carried away by the glamour of Gloria you could even say, as Grace Moore did, that “[Zelda] and Scott always seemed to me straight out of The Beautiful and Damned. “

There was some encouragement for this view in Zelda’s wonderfully entertaining and very personal review of the book.

To begin with,—she wrote—every one must buy this book for the following aesthetic reasons: First, because I know where there is the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Forty-second Street, and also if enough people buy it where there is a platinum ring with a complete circlet, and also if loads of people buy it my husbandneeds a new winter overcoat, although the one he has has done well enough for the last three years.

A little later in the review she remarks: “It seems to me that on one page I recognize a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.” This suggestion that the book is biographical was also encouraged by Hill’s generalized but easily recognizable portraits of the Fitzgeralds on the dust-wrapper. Fitzgerald was half amused and half angry over this wrapper, not, characteristically, because it exploited their private lives, but because he was annoyed by the portrait of himself; he wrote Perkins one of his comically enraged letters about it: “The more I think of the picture on the jacket the more I fail to understand [Hill’s] drawing that man. The girl is excellent of course—it looks somewhat like Zelda but the man, I suspect, is a sort of debauched edition of me….” He went on to observe that though Anthony is “just under six feet… here he looks about Gloria’s height with ugly short legs” and that though Anthony is dark-haired, “this bartender on the cover is light-haired.” Fitzgerald had always wanted to be dark-haired and had always been sensitive about his inadequate five feet eight inches of height, which was mainly a matter of short legs. (“Perfection,” he had noted in his sophomore year in college, “black hair, olive skin and tenor voice.”)

This suggestion that the book had its scandalous side was encouraged by the newspaper paragraphes; “Readers may satisfy their curiosity…” and “… if there is so much smoke…” they said. But one had to be as simple-minded as Grace Moore to know the Fitzgeralds and still be victimized by this idea. Gloria and Anthony were not the Fitzgeralds;they were what the spoiled priest in Fitzgerald thought the Fitzgeralds might become. “Gloria,” he wrote his daughter years later, “was a much more trivial and vulgar person than your mother. I can’t really say there was any resemblance except in the beauty and certain terms of expression she used, and also I naturally used many circumstantial events of our early married life. However the emphases were entirely different. We had a much better time than Anthony and Gloria did.”

They did. They were both at ease as New Yorkers now, and they were having a wonderful time. Moreover, they wanted to see others having a good time. Between them they could create—like young and unhaunted Divers—a charmed and happy world, and they loved doing it. So they played their parts as prince and princess of the confident and eager kingdom of youth with what one of their friends called “an almost theatrical innocence.” These were, of course, expensive roles to play. “It costs more,” as Zelda remembered, “to ride on the tops of taxis… [and] Joseph Urban skies are expensive when they’re real.”

They were expensive, so expensive that Fitzgerald began about this time a lifelong habit of borrowing from his agent. At first his requests that Ober “deposit a thousand” would be made when he could say “am mailing story today.” But gradually he came to anticipate the production of a story, so that for twenty years he was almost constantly behind with Ober. About these calls for help Ober was unfailingly generous, and again and again Fitzgerald would write him: “I must owe you thousands—three at least—maybe more. … I honestly think I cause you more trouble and bring you less business than any of your clients. How you tolerate it I don’t know—but thank God you do.” Ober’s generosity went beyond mere money, as Fitgerald was to realize at the end of his life when he asked for more help than Ober could give. Ober not only lent Fitzgerald money; he took the responsibility forFitzgerald’s financial difficulties as if they were his own. His “we” in the following letter was habitual: “I realize this solves our difficulties only temporarily but if you can finish rewriting the fourth section of the story [Tender Is the Night] in eight or ten days and then take a little rest, I think it would probably be much easier for you to do a short story and I am sure we can survive some way until that is done.”

Though Fitzgerald was aware even in 1920 that their financial problem was more than a joke, he could not help seeing the comedy of it.

… after we had been married for three months I found one day to my horror that I didn’t have a dollar in the world…

I remember the mixed feelings with which I issued from the bank on hearing the news.

“What’s the matter?” demanded my wife anxiously, as I joined her on the sidewalk. “You look depressed.”

“I’m not depressed,” I answered cheerfully; “I’m just surprised. We haven’t got any money.”

“Haven’t got any money,” she repeated calmly, and we began to walk up the Avenue in a sort of trance. “Well, let’s go to the movies,” she suggested jovially.

It all seemed so tranquil that I was not a bit cast down. The cashier had not even scowled at me. I had walked in and said to him, “How much money have I got?” And he had looked in a big book and answered, “None.”

That was all. There were no harsh words, no blows. And I knew there was nothing to worry about. I was now a successful author, and when successful authors ran out of money all they had to do was to sign checks. I wasn’t poor—they couldn’t fool me.

But he was disturbed by this early discovery that the minute he started a novel, or any piece of work that took any time, he sank over his ears in debt. Thus on December 31, 1920, he wrote Perkins:

The bank this afternoon refused to lend me anything on the security of stock I hold—and I have been pacing the floor for an hour trying to decide what to do. Here, with the novel within two weeks of completion, am I with six hundred dollars worth of bills and owing Reynolds $650 for an advance on a story that I’m utterly unable to write. I’ve made half a dozen starts yesterday and today and I’ll go mad if I have to do another debutante which is what they want.

I hoped that at last being square with Scribner’s I could remain so. But I’m at my wit’s end. Isn’t there some way you could regard this as an advance on the new novel rather than on the Xmas sale [of This Side of Paradise] which won’t be due me till July? And at the same interest that it costs Scribner’s to borrow? Or could you make it a month’s loan from Scribner and Co. with my next ten books as security? I need $1600.00.

Anxiously

When everything proper has been said about Fitzgerald’s being in this financial mess after making over eighteen thousand dollars in 1920 and about the transparent exaggeration that The Beautiful and Damned was two weeks from completion (it was not finished until the following April), this remains a touching letter: it is so oviously shocked itself by the amount required that once the awful sum is mentioned it turns tail and runs.

This particular crisis was soon over. This Side of Paradise was at the peak of its sales and Scribner’s were glad to make a little advance against his accumulated royalties; the movies came forward to buy two more stories and to pay three thousand for an option on Fitzgerald’s future output. For the first three years of his career, Fitzgerald had a great success with the movies. He began by selling 'Head and Shoulders' for $2500 to Metro in 1920; it was quickly produced, with Viola Dana and Gareth Hughes, under the impossibly conventional title, The Chorus Girl's Romance. He next sold the same company 'The Off-Shore Pirate,' which was also quickly produced with Viola Dana and Jack Mulhall in the leads. ('The Off-Shore Pirate' was written about a St. Paul girl, Ardita Ford; when the picture reached St. Paul she gave a locally celebrated theatre party so that everyone could 'see what I am like in the movies.') A little later he sold 'Myra Meets His Family' to Fox; it was produced under the title The Husband Hunter with Eileen Percy in the lead. In 1922 he sold the silent rights to THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, NEW YORK, 1922 to Warner Brothers 'for $2500.00 which seems a small price… Please don't tell anyone what I got for it…' (To Maxwell Perkins, April 15, 1922.) Also quickly produced with Marie Prevost and Kenneth Harlan, it was, according to James Gray, 'one of the most horrific motion pictures of memory.' (St. Paul Dispatch, March 2, 1926.) The talking rights to THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, NEW YORK, 1922 seem to have been sold in 1929. In 1923 he sold THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, NEW YORK, 1920 to Famous Players for $10,000, under an arrangement according to which he did a treatment for them. '[Famous Players],' he told an interviewer, 'are going to produce 'This Side of Paradise,' with Glen Hunter in the leading role. I have written first of all a ten-thousand word condensation of my book. This is not a synopsis, but a variation of the story better suited for screening.' (Interview by B. F. Wilson; clipping in Album III.) For some reason nothing ever came of this plan; in 1936 Fitzgerald wrote his daughter: 'Paramount owns the old silent rights but never made it.' (To Frances Fitzgerald Lanahan , July, 1936.) In 1923 he also wrote an original story, called 'Grit,' for the Film Guild, which cast Glen Hunter in the lead. But this kind of rescue by fresh funds solved nothing permanently. It was not until the end of his life that Fitzgerald faced the fact that he had never been “any of the things a proper business man should be” and recognized how “crippled … I am by my inability to handle money.”

Paradoxical as it may sound, Fitzgerald did not care enough about money ever to manage it in a businesslike way. What he did care for was that vision of the good life which he had come to feel was, at least in America, open only to those who command the appurtenances of wealth. Like the Dalyrimple of his own story, who went wrong so successfully, “he had a strong conviction that the materials, if not the inspiration of happiness, could be bought with money.” He strove, therefore, to become a member of the community of the rich, to live from day to day as they did, to share their interests and tastes. “For sixteen years,” he wrote in 1936, “I have lived pretty much as this… person, distrusting the rich, yet working for money with which to share their mobility and the grace that some of them brought into their lives.” He was speaking the simple if complicated truth when he wrote Hemingway, after Hemingway had made a joke about him and the rich in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” “Riches have never fascinated me, unless combined with the greatest charm or distinction.”

But, loving the life of mobility and grace which he saw was open to the rich and which he tried to achieve for himself, he could find nothing to interest him in the means to that life; in fact, the spoiled priest in him had a deep-seated moral distrust of the whole process of money-making, and it is an image of this distrust that Gatsby, with his incorruptible dream of the good life, achieves the means for it by all sorts of underworld activities. Fitzgerald never seriously condemns Gatsby’s illegal business life; he even makes us sympathize with Gatsby when he defends that life against Tom’s condemnation. Fitzgerald could see no real distinction between bootlegging and dealing in stolen liberty bonds on the one hand and, on the other, the kinds of transactions he suspected, after the Harding scandals, that most businessmen were aparty to. He was not at all sure, much of the time, that he could distinguish between these people and a writer with a great gift who wrote superficial stories for the commercial magazines.

The virtues he respected were “honor, courtesy, and courage,” and, in a phrase he marked heavily in his copy of Mencken’s Prejudices, “interior security.” It was the full opportunity for the realization of these virtues in the life of the rich which appealed to him. He admired deeply the rich people who practiced them, and in his generous and unselfish way he gave all rich people the benefit of the doubt, wanting to believe in their heroism. “How I envied you when you knew those people!” he said to Max Perkins once when, walking around a great estate near Baltimore, they met the owner and found he and Perkins had been classmates at Harvard. But such people often disappointed him, and the spoiled priest in him could be very hard on them when they did. They roused in him, as he said, “not the conviction of a revolutionist but the smouldering hatred of a peasant.”

They are—he wrote his daughter late in his life—homeless people, ashamed of being American, unable to master the culture of another country; ashamed, usually, of their husbands, wives, grandparents, and unable to bring up descendants of whom they could be proud, even if they had the nerve to bear them, ashamed of each other yet leaning on each other’s weakness, a menace to the social order in which they live. … If I come up and find you gone Park Avenue, you will have to explain me away as a Georgia cracker or a Chicago killer. God help Park Avenue.

“The idea of the grand dame slightly tight,” he observed on another occasion, “… is one of the least impressive in the world. You know: ‘The foreign office will hear about this, hic!’”

The tension of this “double vision” is apparent in all his heroes. It is in his portrait of Gatsby, the newly rich bootlegger who had grown up on a Minnesota farm and had none of the superficial charm or confidence of the really rich but did have his “heightened sensitivity to the promises of life”; it is in his portrait of Dick Diver, whose father was an impoverished clergyman from Buffalo who nonetheless taught Dick his trick of the heart; it is in his portrait of Stahr, the dispossessed Jew who had fought his way up from the slums of Erie, Pennsylvania, but who had the aristocrat’s gift for understanding and command. The rich, as he remarked at the beginning of one of his finest stories, “are different from you and me” (the second pronoun is important) and this difference fascinated him all his life because for his understanding the circumstances of the very rich provided the perfect occasion for the conflict of good and evil.

There is a fine—though I think largely unconscious—revelation of Fitzgerald’s attitude toward this central subject matter in the ending he sketched but never got written for The Last Tycoon: everything he found in the life of the rich is in it—the opportunity their life offers for the realization of the dream of happiness, the fascination and glitter of its appurtenances, the immorality of its brutal acquisition, and, above all, the crucial moral choice with which it confronts those who live it. A plane in which Stahr is flying from Hollywood to New York crashes in Oklahoma in November. Everyone in it is killed and it remains undiscovered except by two boys, Jim and Dan, who are about fifteen, and a somewhat younger girl, Frances. “Frances comes upon a purse and an open travelling case which belonged to the actress. It contains things that to her represent undreamt of luxuries … a jewel box… flasks of perfume that would never appear in the town where she lives, perhaps a negligee or anything I can think of that an actress might be carrying which was absolutely the last word in film elegance. She isutterly fascinated. Simultaneously Jim has found Stahr’s briefcase—a briefcase is what he has always wanted, and Stahr’s briefcase is an excellent piece of leather—and some other travelling appurtenances of Stahr’s…. Dan makes the suggestion of ‘Why do we have to tell about this? We can all come up here later, and there is probably a lot more of this stuff here….’ Show Frances as malleable and amoral in the situation, but show a definite doubt on Jim’s part, even from the first, as to whether this is fair dealing even toward the dead.” Eventually Jim’s conscience drives him to tell the authorities of their discovery. “There will be no punishment of any kind for any of the three children. Give the impression that Jim is all right—that Frances is faintly corrupted and may possibly go off in a year or so in search of adventure and may turn into anything from a gold digger to a prostitute, and that Dan has been completely corrupted and will spend the rest of his life looking for a chance to get something for nothing.”

This is to see, in a way not unlike Henry James’, that one of the central moral problems is raised in American life in an acute form among the rich, in the conflict between the opportunities for being “all right” and for being “completely corrupted” which exist for them. Thus the spoiled priest in Fitzgerald found the conflict he was seeking at the very heart of the world the romantic young man’s imagination responded to with such eagerness.

Next chapter 7

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).