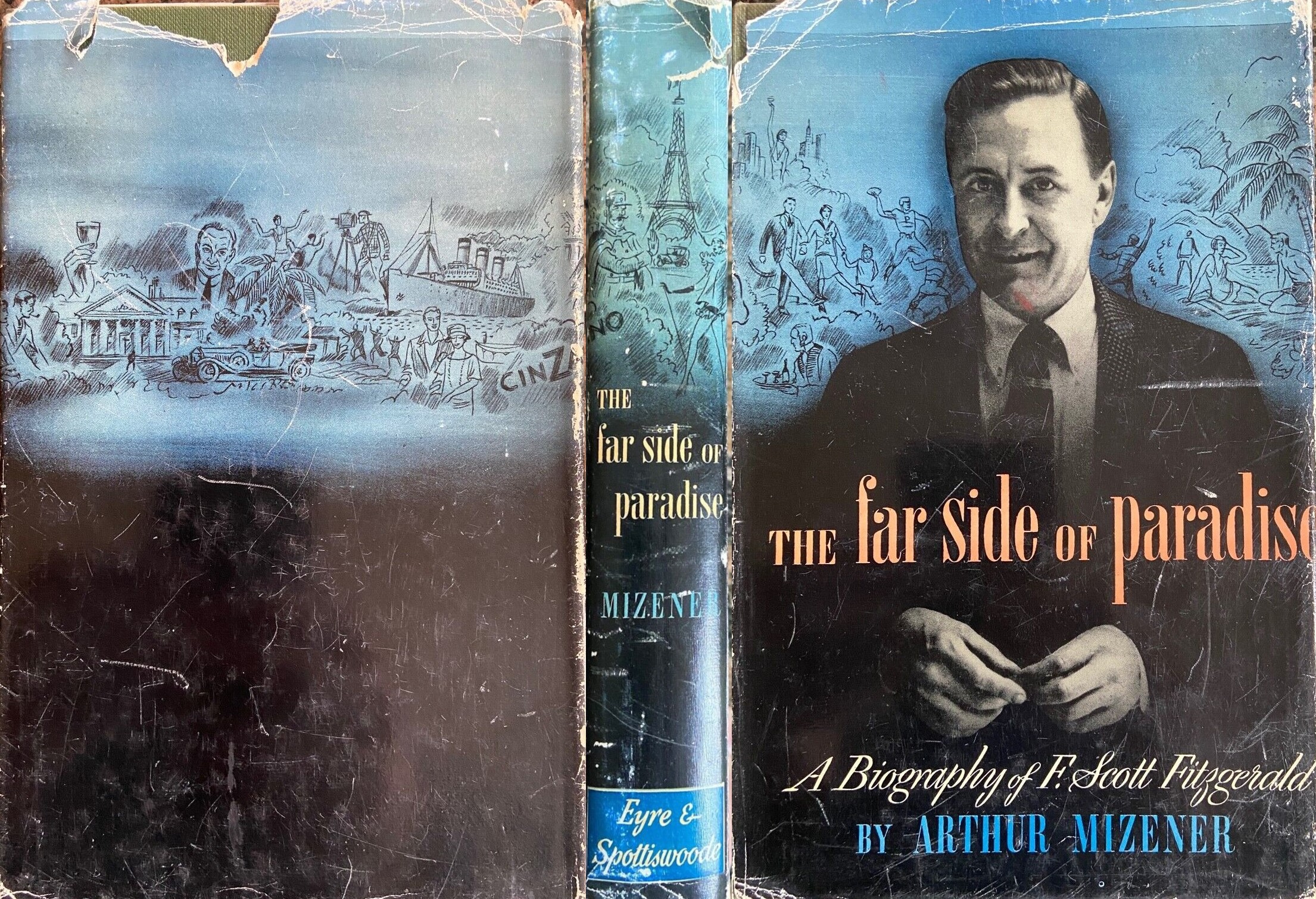

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter II

Fitzgerald came on to Princeton in the middle of September of 1913 to take the examinations which would determine whether he was to be admitted. On the twenty-fourth he was able to wire his mother: ADMITTED SEND FOOTBALL PADS AND SHOES IMMEDIATELY PLEASE WAIT TRUNK. He Settled for his freshman year into the rambling stucco warren at 15 University Place.

The Princeton to which he was then admitted was a very different place from the present Princeton. It was essentially an undergraduate college, though the Graduate College was dedicated the fall Fitzgerald arrived. Its enrollment was around 1500; it had a good undergraduate library of about 300,000 volumes; it had just begun to feel the effect of the preceptorial system introduced under President Wilson, who had recently escaped from an unhappy situation at the University into the governorship of New Jersey and had been replaced by John Grier Hibben.

Physically Princeton still centered in the old campus above the transverse line set by McCosh Walk, though some of the new dormitories on the lower campus such as Little, Patton, and Cuyler had been built. The railroad station still stood at the foot of Blair steps, and the old Casino, where the Triangle Club rehearsed, stood not far off. The rickety but partly eighteenth-century façade of Nassau Street had not yet been replaced by faked Georgian; Nassau Street itself was unpaved. The modern undergraduate commons on the corner of University Place and Nassau Street would not be built for two more years; Palmer stadium was under construction and would first be used for the Dartmouth game in the fall of Fitzgerald’s sophomore year (Fitzgerald first saw “the romantic Buzz Law kicking from behind his own goal line with a bloody bandage round his head” on University Field on Prospect Street).

Pause some evening—wrote V. Lansing Collins in 1914—beneath the windows of any dormitory on the campus…. From one room comes the rapid clicking of a typewriter where someone is getting out a report or an essay … in another room are three or four men hotly arguing some triviality of college politics; across the way a talking machine is reproducing the latest Broadway success; elsewhere an impromptu quartet of piano, violin, guitar, and mandolin is reminding nobody of the Kneisels or the Flonzaleys….

This sounds typical of undergraduate life at almost any time, save that the overtones of the age of guitar and mandolin are still evident. They were soon to fade, however. The Princeton modification of hazing, known locally as “horsing”—it consisted in forcing freshmen to sing or recite, or to march to commons in “lockstep express”—was officially abolished altogether in the spring of 1914. The rushes—battles between freshmen and sophomores—continued for only a few years longer, though Fitzgerald was proud to have his picture taken to show his battered condition after one of them. The fact revealed by “an official census” that there were only six undergraduate automobiles in Princeton in 1913 was soon to seem astonishing. It was, as Dean Gauss remarked years later, “the Indian Summer of the ‘College Customs’ era in our campus life,” an era which was gradually dying and was to be abruptly closed by the country’s entrance into the war.

Meanwhile, however, it was a small world, as perhaps theundergraduate world always is. Most of its standards and traditions had come down to it very little changed from the nineties and this was largely true of the curriculum as well as of undergraduate mores. “… Ernest Dowson and Oscar Wilde were the latest sensational writers who had got in past the stained glass windows [of the library],” as Edmund Wilson remembered. John Peale Bishop, a sympathetic observer, described it as a place where

… nothing matters much but that a man bear an agreeable person and maintain with slightly mature modifications the standards of prep school. Any extreme in habiliment, pleasures or opinions is apt to be characterized as “running it out,” and to “run it out” is to lose all chance of social distinction….

These somewhat naive standards may be violated on occasion by the politician or the big man, but to the mere individualist they will be applied with contempt and intolerance.

Football was a deadly serious affair; the Big Three were still really big, so that football, it could be felt, was a game conducted by gentlemen in a kind of Tennysonian Round-Table spirit. No editorial writer on the Daily Princetonian ever questioned the idea that the success or failure of a university year depended on the results of the Yale and Harvard games, and Fitzgerald, at a time when he was by no means a simple disciple of the conventional Princeton attitude, could write in This Side of Paradise: “There at the head of the white platoon marched Allenby, the football captain, slim and defiant, as if aware that this year the hopes of the college rested on him, that his hundred-and-sixty pounds were expected to dodge to victory through the heavy blue and crimson lines.” Questions of the intercollegiate regulation of major sports were conducted at the high diplomatic level by consultations among the captains of the Big Three teams andtheir decisions were solemnly canvassed at the universities and in the metropolitan press.

Football was the best means to social distinction on the campus, and social distinction, as the quotation from John Peale Bishop shows, was the main preoccupation of the first two years of an undergraduate’s career. The competition was no less fierce because its most inviolable requirement was that the contestants should appear quite unconcerned with social prestige. Beneath this pretense of indifference the game of becoming a Big Man was carried on day in and day out by everyone who had, by local standards, good sense. “From the day when, wild-eyed and exhausted [from the rush], the… freshmen sat in the gymnasium and elected some one from Hill School class president … up until the end of sophomore year it never ceased, that breathless social system, that worship, seldom named, never really admitted, of the bogey ‘Big Man.’” … “all the petty snobbishness within the prep-school, all the caste system of Minneapolis, all were here magnified, glorified and transformed into a glittering classification.”

There were besides football other, though less powerful, means of becoming a Big Man; other sports which drew crowds counted, though, as Bishop noted, “Closet athletics, such as wrestling and the parallel bars, are almost a disadvantage.” After football the most powerful organization socially was the Triangle Club which, by an incredible consumption of undergraduate time and energy, produces annually a commonplace musical comedy. After the Triangle Club, the Daily Princetonian was the most reputable pursuit for an undergraduate, and after that what Bishop called “the Y.M.C.A. in a Brooks suit”—the Philadelphian Society—and The Tiger.

All this energetic pursuit of extracurricular activities received its reward at the time of club elections in the middle of the sophomore year. The Princeton clubs come as near tobeing purely social institutions as such organizations ever can, and it is this very purity which sets the limits to their influence. A Yale senior society or an ordinary fraternity chapter, which does perform a serious function however limited or misdirected it may be, offers its members something to work for and even believe in. A Princeton club, apart from providing a place to eat, to play billiards, and to take a girl on week-ends (and nowadays, though not in Fitzgerald’s day, a bar and a television set), does not even pretend to offer anything. The function of the Princeton clubs is to provide a system of grading people according to social distinction at the middle of the sophomore year. Once that is done, their serious purpose has been fulfilled. Perhaps the classic statement about the Princeton clubs was made by the group of sophomores who refused to join any club in the spring of 1917. “Making a club is usually considered the most important event in college life. Not to make a club constitutes failure; and a man’s success is measured by the prestige of the club to which he is elected. In order to achieve this success, a man must repress his individuality enough to conform to the standards which the upper-classmen may determine”—“standards,” as a sympathetic Princetonian editorial added, “… which… have been uniformly bad, almost as bad as they could be.” For the last two years of an undergraduate’s life the clubs then provide him with a gathering place patterned on the best country-club models where he eats and enjoys the wonderful leisure of undergraduate years in luxurious surroundings with congenial companions—if in the scramble of other considerations he has been lucky enough to fall among friends.

But if this was the dominant world of the University, Princeton was also a place in which Scott Fitzgerald, going out for dinner during the September examination period before commons were open, could sit down at the Peacock Inn next to an aristocratic-looking boy, and while “in the leafystreet outside the September twilight faded [and] the lights came on against the paper walls, where tiny peacocks strode and trailed their tails among the gayer foliations,” he and Bishop could talk and talk about books, about Stephen Phillips and Shaw and Meredith and the Yellow Book. It is true that as they talked Fitzgerald appears to have worried for fear the “St. Paul’s crowd at the next table would… mistake him for a bird, too…” and he would injure his social standing. Still, that intellectually admirable world was there. It had been built up through two college generations under the leadership of T. K. Whipple and Edmund Wilson and it was, before the war broke its tradition too, to include, besides Bishop, the versatile Stanley Dell, John Biggs, Jr., and Hamilton Fish Armstrong. Fitzgerald was going to turn to this group at the end of his college career and to say many years later, without qualification and undoubtedly with some exaggeration: “I got nothing out of my first two years [in college]—in the last I got my passionate love for poetry and historical perspective and ideas in general (however superficially), that carried me full swing into my career.”

But if this is an oversimplified view of his career it is a tribute to what this group did for him which is deserved; they gave him the only education he ever got, and, above all, they gave him a respect for literature which was more responsible than anything else for making him a serious man. The voice of conscience which had taken form under these pressures spoke when Fitzgerald wrote sadly to his old friend, John Biggs, about Biggs’ appointment to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals as the youngest judge in the history of that court: “I hope you’ll be a better judge than I’ve been a man of letters.” This was a professional conscience. If Princeton was a place of provincial social competition for two years and of charming relaxation for two more, and if it was academically a place where, as Fitzgerald himself remarked, too often “in the preceptorial rooms… mildly poetic gentlemen resented any warmth of discussion and called the prominent men of the class by their first names,” it was also a place where people with intellectual interests could educate themselves.

These people were committed to high standards and maturity of judgment; they wrote for each other as best they could without embarrassment or inhibition. Some of the literary expectations of the time have been betrayed by changes in ambition or personal defeats; but very few of its judgments seem, thirty years after, to have been wrong. They belonged, these writers, as Edmund Wilson remarked long after,

to a kind of professional group, now becoming extinct and a legend, in which the practice of letters was a common craft and the belief in its value a common motivation…. [They] saw in literature a sphere of activity in which they hoped themselves to play a part. You read Shakespeare, Shelley, George Meredith, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, and you wanted, however imperfectly and on however infinitesimal a scale, to learn their trade and have the freedom of their company. I remember Scott Fitzgerald’s saying to me, not long after we got out of college: ‘I want to be one of the greatest writers who have ever lived, don’t you?’ I had not myself really quite entertained this fantasy because I had teen reading Plato and Dante. Scott had been reading Booth Tarkington, Compton Mackenzie, H. G. Wells and Swinburne; but when he later got to better writers, his standards and achievements went sharply up, and he would always have pitted himself against the best in his own line that he knew. I thought his remark rather foolish at the time, yet it was one of the things that made me respect him; and I am sure that his intoxicated ardor represented the healthy way for a young man of talent to feel.

However far this world was, in its essential values, from the ordinary social world of Princeton, the two of course overlapped; Princeton was a small place. Both Wilson and Bishop were in the Triangle Club. Wilson even wrote the book for the Triangle’s 1915-1916 show called “The Evil Eye.” He started with the idea that he could do something brilliant and ended with the feeling that, under the usual pressures, he had produced just another musical comedy. “I am sick of it myself,” he wrote Fitzgerald when he had finished the first draft. “Perhaps you can infuse into it some of the fresh effervescence of youth for which you are so justly celebrated.” For by this time Fitzgerald was a considerable figure in the Triangle Club and was as a matter of course to write the lyrics for what Dean Gauss was later to call the “most serious of all [Wilson’s] literary péchés de jeunesse. “

It was Dean Gauss too, however, who remarked with amusement that, for all Wilson’s boredom with the play, it was “a bit too exotic and literary … [for] the older wearers of Triangle charms.”

One could not, to be sure, be a really big man without pretty well accepting the mores of the social world and going out for the right things and avoiding the wrong, but the two worlds tolerated each other, so that the Princeton Pictorial Review could write an editorial supporting “running it out,” and the Nassau Lit could take up questions of campus politics. If Wilson went his sure way toward his unobtrusive, thorough, and humane learning and toward the mastery of a craft whose demands he had always understood and never underrated, he could at the same time participate in the life of the social world, writing, not very seriously perhaps, his Triangle show, being elected to a good but not big club, being good-humoredly selected by his classmates at the end of four years as “the worst poet” they knew. It is typical of the social world’s kind of tolerance that Fitzgerald should have remembered the undergraduate Wilson as “the shy little scholar of Holder Court.” It is also typical of theliterary world that Wilson, thinking of how Fitzgerald first called on him with a story, should have remembered that

I climbed, a quarter-century and more

Played out, the college steps, unlatched my door,

And, creature strange to college, found you there:

The pale skin, hard green eyes, and yellow hair—

Intently pinching out before a glass

Some pimples left by parties at the Nass;

Nor did you stop abashed, thus pocked and blotched,

But kept on peering while I stood and watched.

The two worlds thus lived together with only the occasional strain of a rebellion against the club system to mar their sympathy, and many undergraduates doubtless lived out their college careers according to the ostensible conventions of the society largely unaware of how a man really becomes Big. It was a perfectly healthy society set in an old and homogeneous small town. Years after, in a passage in his Notebooks, Fitzgerald compared it with modern Princeton:

Once upon a time Princeton was a leafy campus where the students went in for understatement, and if they had earned a P, wore it on the inside of the sweater, displaying only the orange seams, as if the letter were only faintly deserved. The professors were patient men who prudently kept their daughters out of contact with the students. Half a dozen great estates ringed the township, which was inhabited by townsmen and darkies—these latter the avowed descendents of body servants brought north by southerners before the Civil war.

Nowadays Princeton is an “advantageous residential vicinity”—in consequence of which young ladies dressed in riding habits, with fashionable manners, may be encountered lounging in the students’ clubs on Prospect Avenue. The local society no longer has a professional, almost military homogeneity—it is leavened with many frivolous people,and has “sets” and antennae extending to New York and Philadelphia.

As such a society, the old Princeton had, within the narrow area of activity established by its ideals, its conceptions of honor and duty, its heroes and men of integrity, its occasions of difficult moral choice. Its worst fault was its failure, inherent in the conditions necessary to education, to provide extracurricular activities with practical consequences in the real world, thus forcing the ordinary, unintellectual undergraduate to devote his energy to social achievement and games. It is certainly better for undergraduates to see football players and Triangle authors and Princeton gentlemen, all of whom have skills and gifts of a kind, as heroic figures of a serious world, in the way Fitzgerald did, than to take the cynical attitude toward these things of later, more sophisticated undergraduates. It committed them to a kind of order; “For at Princeton, as at Yale, football became, back in the nineties, a sort of symbol…” as Fitzgerald said. “It became something at first satisfactory, then essential and beautiful. It became… the most intense and dramatic spectacle since the Olympic games. The death of Johnny Poe with the Black Watch in Flanders starts the cymbals crashing for me, plucks the strings of nervous violins as no adventure of the mind that Princeton ever offered.”

Fitzgerald plunged eagerly into the life of Princeton. His first impulse was to accept its standards, to admire its heroes, to use his imagination to make his participation in it seem even more dazzling than it otherwise would have. As the university where the honnêtes hommes of the American bourgeoisie were supposed to concentrate—as contrasted with Yale, the university where the ambitious went, and Harvard, the university of intellectuals and individualists—Princeton had a special appeal for Fitzgerald, with his feelings of social uncertainty and his desire for social success andsecurity. That it was also the university of Southern gentlemen only strengthened his admiration of it. “I think of Princeton,” said Amory Blaine in This Side of Paradise, “as being lazy and good-looking and aristocratic.” Fitzgerald’s acceptance of Princeton did not, of course—such commitments never did—prevent the shrewd, observing part of his mind from seeing what the forces which made for success were; but neither did his almost Machiavellian grasp of the political realities of the system and the worth of some of its big men affect his admiration of it or his determination “to become one of the gods of the class.” All his life he made this kind of approach to a new world.

[His winter dreams]—as he wrote later of the hero of “Winter Dreams”—persuaded [him] … to pass up a business course at the State university… for the precarious advantage of attending an older and more famous university in the East, where he was bothered by his scanty funds. But do not get the impression, because his winter dreams happened to be concerned at first with musings on the rich, that there was anything merely snobbish in the boy. He wanted not association with glittering things and glittering people—he wanted the glittering things themselves. Often he reached out for the best without knowing why he wanted it….

The Fitzgerald of 1913—he was seventeen years old the day he was admitted to Princeton—was a small boy (five feet seven), slight and slope-shouldered in build, almost girlishly handsome, with yellow hair and long-lashed green eyes which seemed, because of the clearness of their whites, to stare at people with a disconcerting sharpness and curiosity. “He had rather a young face, the ingenuousness of which was marred by the penetrating green eyes fringed with long dark eyelashes,” says This Side of Paradise of Amory Blaine at this age; and

The glitter of the hard and emerald eyes[,]

The cornea tough, the aqueous chamber cold,

is the clearest detail in Wilson’s memory of Fitzgerald’s physical appearance as an undergraduate. His remarkable pallor reinforced the effect of his eyes. He wore the correct clothes and labored to acquire the proper manners and mannerisms, the high stiff Livingston collar with the narrow opening and rounded points or the equally high button-down collar with the deliberate bulge, the dark tie, the narrow-cuffed white flannels, or the tight knickers, the high-buttoned vest and jacket, the casual almost slouching posture, the swooping handshake. But the very earnestness with which he stalked convention betrayed him. All the energy of his disturbing talent for transforming imaginatively the actual world into an adequate vehicle for his immature but deeply felt vision of the good life had been applied to the Princeton ideal of the gentleman, so that the very completeness of his conformity and the dramatic intensity of his performance of the part of an average undergraduate made him stand out as an odd and unusual person. It was the essence of the Princeton manner to appear not to take the deadly game of social competition seriously; but Fitzgerald, with his lifelong habit of “taking things hard,” his anxiety to succeed and to be liked and admired, could not manage that most essential part of the pose. He worried, much too visibly, over the details of his performance; it was a failing he never conquered: twenty-five years later he was still fussing at his hostess at a house party in Tryon to know if his sports jacket were “all right.” (“A gentleman’s clothes may be right or wrong,” his hostess remarked, “but he is never self-conscious about them and he certainly never talks about them.”) “I can’t drift,” says Amory Blaine “—I want to be interested. I want to pull strings, even for somebody else, or be Princetonian chairman or Triangle President. I want to be admired, Kerry.” So did Fitzgerald.

One of his classmates remembers an occasion early in their freshman year when Joe McKibben, an upperclassman from St. Paul, took him and Fitzgerald walking along the old canal with another upperclassman. Fitzgerald bounded around and was boyish and talkative in a harmless way. The next day when they met outside a classroom Fitzgerald rushed up to his friend and said: “Do you know who that was we were walking with yesterday?—That was George Phillips, the varsity tackle!” His classmate said he knew that. “But my gosh, why didn’t you tell me! I made a fool of myself, didn’t I?” To discuss the matter in this open way was to disregard the decencies of the situation.

As the telegram announcing his admission indicates, Fitzgerald began by trying to be a football hero, but at one hundred and thirty-eight pounds his chances of success were not good even had he had any natural talent or liking for the ‘ game. He lasted just one day on the freshman squad. The initial failure did not daunt him at the time, but it meant there was one kind of god he would never be and the realization left its scar, a lifelong habit of daydreaming a story which he had first written out as a student at St. Paul Academy. He described this dream in his essay on insomnia called “Sleeping and Waking.”

“Once upon a time” (I tell myself) “they needed a quarterback at Princeton, and they had nobody and were in despair. The head coach noticed me kicking and passing on the side of the field, and he cried: ‘Who is that man—why haven’t we noticed him before?’ The under coach answered, ‘He hasn’t been out,’ and the response was: ‘Bring him to me.’

“… we go to the day of the Yale game. I weigh only one hundred and thirty-five, so they save me until the third quarter, with the score—“

—But it’s no use—I have used that dream of a defeated dream to induce sleep for almost twenty years, but it has worn thin at last.

But there were other ways to prestige. He went out for The Tiger and—probably at Bishop’s urging—for a part in the English Dramatic Association’s annual play. Though he was tentatively cast, he quickly dropped out of the EDA; it was not an organization with much prestige. But he had a contribution in the first issue of The Tiger. Most important of all, he went to the organization meeting of the Triangle Club in October and was busy for the next two months helping with suggestions for lyrics and laboring over the lights during rehearsals in the old Casino. By February he was hard at work on a libretto which he hoped would be accepted for the next year’s Triangle show. By that date he was also deep in academic difficulties. As early as October 7 the dean had called him into consultation on this question and now the midyear examinations showed the full extent of his troubles; he had failed three subjects, acquired fifth groups in three others, and made one fourth group—in English. [Grades at Princeton run downward from first to seventh group. Groups one to five are passing, six and seven failures. The groups span approximately ten points each on a scale of one hundred.] This dismal record resulted in spite of his having devised what was considered to be the perfect stall for the question which caught him napping in class: “It all depends on how you look at it. There is the subjective and objective point of view.”

Throughout the spring he continued to work hard on his Triangle show and grew intimate with Walker Ellis, a handsome and romantic junior from New Orleans who was now the president-elect of the Triangle. Through the spring he watched with fascination the club elections and, carried away by the wonderful New Jersey spring, began to think of himself as a dedicated romantic nature and to discuss all the aspects of this commitment with his friend Sap Donahoe. He also took to walking in the beautiful gardens of the Pyne estate and watching the swans in the pools. Father Fay, a converted Episcopalian who had taken Fitzgerald up when he had been a student at Newman, came to the campus fromtime to time during the year and took him out to dinner with a few other carefully selected undergraduates. That spring he invited Fitzgerald to his mother’s home at Deal for a weekend and Fitzgerald was dazzled by the mixture of luxury and intellectual life he found. With his usual combination of innocence and calculation he played the eager, ingenuous boy; one guest who met him at Deal called him “a prose Shelley.” There was of course much very real naïveté in him at this point in his career and all his life he appeared more naive than he was because he was so direct and effervescent. Moreover, he had had very little experience of the sophisticated eastern rich and Fay’s world doubtless seemed to him the perfect fulfillment of the simpler St. Paul society in which he had never felt secure. To be intimately at home in Fay’s world was really to succeed.

Father Fay was a man of taste and cultivation who, having never known anything but the life of the well-to-do, had that unconscious ease and security in it which Fitzgerald always envied and never could achieve. In addition to these qualities he was something of an eighteen-nineties aesthete, a dandy, always heavily perfumed, and a lover of epigrams. To a schoolboy of both social and literary ambitions this combination of characteristics must have been nearly irresistible. As a convert to Catholicism Fay could sympathize with Fitzgerald’s dislike of the dreary side of his Irish Catholic youth and also show him a Catholicism which was wealthy and cultivated and yet secure in its faith. “… he [Shane Leslie] and another [Fay], since dead,” Fitzgerald wrote several years later, “made of that church a dazzling, golden thing, dispelling its oppressive mugginess and giving the succession of days upon gray days, passing under its plaintive ritual, the romantic glamour of an adolescent dream.”

As a man of taste and intellectual interests, Father Fay understood all Fitzgerald’s ambitions and doubts. At the same time he had a gift for getting on an intimate footing withyoung men of Fitzgerald’s age, and, delighting in him, exercised that talent so that Fitzgerald found him sympathetic and understanding and talked with him as an equal. Fay was presently to be a Monsignor and, as a friend of Cardinal Gibbons and the occasional diplomatic representative of the Vatican, he had already considerable position and influence in the church. He was a romantically satisfying figure. There is no doubt that Fay did a great deal for what Shane Leslie, the Irish novelist and critic, called “the crude, ambitious schoolboy” who arrived at Newman from St. Paul, and, until he died very suddenly in the influenza epidemic in 1919, Fay was probably the greatest single influence on Fitzgerald. How much Fitzgerald admired him is clear from the portrait of him as Father Darcy in This Side of Paradise and from the dedication of the book to him (even though his name is misspelled in it. When Fay died on January 10, 1919, Fitzgerald and Zelda imagined they had a premonition of disaster. As they sat together on the couch in the Sayres' living room, they were seized by uncontrollable fear. They learned of Fay's death the next day. (ZELDA SAYRE FITZGERALD to H. D. Piper.) The description of Father Darcy's funeral in THIS SIDE OF PARADISE (pp. 286-87) is taken from the description of Fay's funeral Leslie sent Fitzgerald, January 16, 1919) Such need as there was in Fitzgerald’s nature for a father was fully satisfied by him. “… the jovial, impressive prelate who could dazzle an embassy ball, and the green-eyed, intent youth… accepted in their own minds a relation of father and son within a half-hour’s conversation,” says Fitzgerald of Monsignor Darcy and Amory Blaine.

The flavor of their relation can still be felt in Fay’s letters. They are addressed to “Dear Old Boy” or “Dear Boy” and a characteristic one runs:

July 9,1917

I was very glad to get your letter. It was an amusing letter, although one can see that you are frightfully bored.

I am jolly glad about the poetry. Do get it done as quickly as possible and let me know about the commission…. We had a good jaw at the club, did we not? I enjoyed it immensely. It is always so entertaining to talk about oneself. …

What you say about the Manlys is most amusing…. That is so like what I would have done at your age.

Do write me soon. I mean to say, whenever the spirit moves you.

Best love, Cyril Fay

“So they talked,” as This Side of Paradise says, “often about themselves, sometimes of philosophy and religion, and life as respectively a game or a mystery. The priest seemed to guess Amory’s thoughts before they were clear in his own head, so closely related were their minds in form and groove.” The account of Amory and Darcy in This Side of Paradise, with its amazing honesty, shows more clearly than anything the tangle of affection and sympathy, of social and intellectual snobbery, of literary attitudinizing and wisdom, of innocence and calculation which constituted the relation between Fitzgerald and Fay.

“I think when we write one another,” said Fay, “we ought always to think of the possibility of the other person some day publishing that letter.” He was right. Fitzgerald used three of Fay’s letters and one of his poems in This Side of Paradise with only the slight changes necessary to make them fit the fictional situation. What is even more surprising is the revelation of how Fay talked to Fitzgerald; the episode of Eleanor Savage, for example, was an experience of Fay’s youth he had told Fitzgerald about. When Fitzgerald sent Fay his version of the episode for The Romantic Egotist, Fay was unperturbed, indeed fascinated: “The two chapters… gave me a queer feeling. I seemed to go back twenty-five years. Of course you know that Eleanor’s real name was Emily. I never realized that I told you so much about her…. How you got it in I do not know…. Really the whole thing is most startling. … I suppose this is most ill-advised talk on my part, but really I cannot be bothered with the hypocracy of an elder…” Thus Fitzgerald was probably right when he told Shane Leslie that “I really don’t think he’d have minded” about the letters and the poems.

With this important visit with Fay at Deal Fitzgerald completed his freshman year. The rest of his life he liked to remember that he had flunked practically everything that year in order to write the Triangle show. “I spent my entire freshman year,” he said later, “writing an operetta for the Triangle Club. To do this I failed in algebra, trigonometry, coordinate geometry and hygiene.” But in fact three of these four failures were in the first term and his June record, with only one failure, was a great improvement over February; he even raised his English mark to a third group. He took forty-nine cuts, the maximum allowed without penalty.

That September the Elizabethan Dramatic Club staged the last of its annual plays. This time Fitzgerald wrote for them a farce about a man who wishes to buy a house and tries to get it cheap by persuading the owners it is haunted. The elaborate make-believe of other years as to organization and purpose was continued: “Assorted Spirits” was “produced under the management of G. B. Schurmeier”; it was “Presented by the Elizabethan Dramatic Club for the Benefit of the Baby Welfare Association”; it was directed by Miss Elizabeth Magoffin. But all these names were really fronts for Scott Fitzgerald. He wrote the play, organized the production, directed, and acted. The play was apparently a competent farce, and, together with the public interest in what the society pages liked to call “juvenile St. Anthony Hill,” made for a success. The Baby Welfare Association netted three hundred dollars and the play was given a second time at the White Bear Yacht Club. On this second occasion there was a near panic. In the midst of one of the ghost scenes the main fuse burned out with a loud explosion; women shrieked and prepared to faint. “Scott Fitzgerald the 17-year-old playwright proved equal to the situation however and leaping to the edge of the stage quieted the audience with an improvised monologue… The youthful playwright actor held the attention of the 200 men and women and in a few minutes the electrician had repaired the lights and the play proceeded.” Fitzgerald used the experience of this little crisis in his story “The Captured Shadow.”

Meanwhile, in spite of all the work he was doing on “Assorted Spirits,” he managed to get in enough tutoring to, go back to Princeton early and to pass off enough conditions to become a sophomore in precarious “good standing.” The Committee on Non-Àthletic Organizations, however, found his standing too insecure to allow him to participate officially in the Triangle Club. It puzzled and angered him to find that important things like the Triangle Club and his career as a Big Man could be interfered with by the academic authorities and he was presently to write a story about this experience of taking make-up examinations called “The Spire and the Gargoyle,” in which the Spire is the imitation Gothic architecture of Princeton which stands for all the romantic success Fitzgerald dreamed of and the Gargoyle the instructor who graded his make-up examination. The irony of the story depends on the absurdity of a superior and more sensitive person like Fitzgerald’s finding himself at the mercy of this pathetic worm. This is the perennial undergraduate attitude, of course, but Fitzgerald’s version of it has a kind of classic perfection.

For the moment, however, the gargoyle was cowed and Fitzgerald promptly forgot the possibility that he might vent his spleen again later, for he was swept away in the excitement of having his Triangle show accepted in September. His friend Walker Ellis was partly responsible for his triumph, but having done some revision on the dialogue—mostly, as a faculty reviewer noted in the Princetonian, the addition of faintly disguised borrowings from Wilde and Shaw—Ellis put himself down as the author of the book, leaving Fitzgerald credit only for the lyrics (in his own copy of the program, Fitzgerald has pencilled in corrections which make the credits read: “Book and lyrics by F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1917. Revision by Walker M. Ellis, 1915.” This description represents the facts). Unable to accept the part he had been cast for or to go on the Christmas trip because of his ineligibility, Fitzgerald nonetheless threw himself into the work of producing the show, pulling wires for others insteadof himself when it came to parts, working to get his friends into the chorus, and devoting the better part of a solid month to rehearsals. In the intervals he worried about the club elections which would come in the spring.

The show itself—entitled Fie! Fie! Fi-Fi!—is a Graustarkian melodrama about a prime minister of Monaco who is ousted by an ex-gangster and saloonkeeper from Chicago and reinstated through the machinations of the gangster’s estranged but undivorced wife, temporarily a manicurist at the hotel. It had a successful tour and Fitzgerald’s lyrics were much praised. He had been studying his Gilbert as the “Chatter Trio” of Act I shows:

I’d like to hear a reason for this terrible commotion,—

But if you try to talk so much I can’t get any notion;

So restrain yourselves and take your time and let’s discuss the question.

You act as though you had a touch of chronic indigestion—

And as I need a lot of time for ev’ry mental action;

Kindly ease your flow of English, or you’ll drive me to distraction.

His remarkable verbal facility stood him in good stead in this business; once, when Hooper, the coach, found fault with a song, Fitzgerald went to the back of the old Casino and, while the chorus ran through a number, produced a new and better lyric.

While the Triangle was touring as far west as Chicago and St. Louis in the customary haze of alcohol and débutantes, Fitzgerald went home to St. Paul for Christmas. By now he had become a figure there, a somewhat uncertain quantity, perhaps, but a handsome young man who was making a success at Princeton and likely to become a Big Man. When it became known that “Midge” Hersey was bringing home for a vacation visit her Westover roommate, Ginevra King, it was expected that an interesting passage at arms between her and Fitzgerald was bound to occur. Ginevra King was acelebrity, a beautiful and wealthy girl from Chicago who had already acquired a reputation for daring and adventurousness. Fitzgerald let it be known that, though he had originally not planned to spend the vacation in St. Paul, he might undertake to stay if Miss King interested him. Thus warily the two champions approached one another. It was not, however, till January fourth, at a dinner at the Town and Country Club, that they met. The scene is described with great precision in a story Fitzgerald wrote for the Nassau Lit two years later: “Isabelle and Kenneth were distinctly not innocent, nor were they particularly hardened…. When Isabelle’s eyes, wide and innocent, proclaimed the ingenue most, Kenneth was proportionally the less deceived. He waited for the mask to drop off, but at the same time he did not question her right to wear it. She, on her part, was not impressed by his studied air of blase sophistication. She came from a larger city and had slightly an advantage in range. But she accepted his pose. It was one of the dozen little conventions of this kind of affair. … So they proceeded, with an infinite guile that would have horrified the parents of both.” Nevertheless, up to the limit of his still immature capacity, Fitzgerald fell in love. For Ginevra, he became for a time the most important of her many conquests. As she said herself many years later, “… at this time I was definitely out for quantity not quality in beaux, and, although Scott was top man, I still wasn’t serious enough not to want plenty of other attention!” For all that he was in love, Fitzgerald understood her attitude. “The future vista of her life,” he wrote of Isabelle, “seemed an unending succession of scenes like this: under moonlight and pale starlight, and in the backs of warm limousines and in low, cosey roadsters stopped under sheltering trees—only the boy might change….” But for Fitzgerald the girl would not. There were, of course, plenty of other girls, for he was at the age when social life consists largely of mild flirtations, and he , had a dozen such encounters at house parties and during vacations in the next couple of years. But in his schoolboy way he never faltered in his devotion to his Westover Cynara. To the end of his life he kept every letter she ever wrote him (he had them typed up and bound; they run to 227 pages). Born and brought up in the best circumstances in Chicago and Lake Forest, Ginevra moved for him in a golden haze of habit, assumption, gesture, made up of a lifetime of wealth and ease, of social position always taken for granted, of country clubs and proms which she dominated as if such authority were her natural prerogative. When Fitzgerald wanted to realize this feeling in his story, “Winter Dreams,” he portrayed himself as Dexter Green, whose father was a grocer and whose “mother’s name had been Krimslich … a Bohemian of the peasant class… [who] had talked broken English to the end of her days”; Dexter Green had been a caddy, worked his way through college, and was as a young businessman “making more money than any man my age in the Northwest.” Fitzgerald portrayed Ginevra in the story as Judy Jones, whom Dexter saw always in a “soft deep summer room” peopled with the men who had already loved her, “the men who when he first went to college had entered from the great prep schools with graceful clothes and the deep tan of healthy summers,” or swimming in the moonlight alone and moody at expensive summer resorts, or at dances, “a slender enamelled doll in cloth of gold” who had just “passed through enchanted streets, doing things that were like provocative music.” “Whatever Judy wanted, she went after with the full pressure of her charm.” Like Gatsby with Daisy, Dexter knew she “was extraordinary, but he didn’t realize [until he knew her well] just how extraordinary a ‘nice’ girl could be.”

Ginevra, the extraordinary “nice” girl, the beautiful, magnetic girl who was always effortlessly at ease and sure seemed like this to Fitzgerald, with his imagination, his genteel poverty, and his uncertainty. The other men were part of hercharm, for though she conquered everywhere quite deliberately, she remained essentially untouched, free. This was the girl he was, without much conscious intention, to make the ideal girl of his generation, the wise, even hard-boiled, virgin who for all her daring and unconventionality was essentially far more elusive than her mother—and, in her own way, far more romantic. He could see the naïveté and innocence of this girl temporarily in search of pleasure but seriously desiring some not very clearly defined romantic future, and it only made her seem to him more poignant: Judy Jones is wholly defeated in the end. Thus Fitzgerald was something more than one of Ginevra’s conquests; what he loved was the substance she gave to an ideal to which his imagination clung for a lifetime. To the end of his days the thought of Ginevra could bring tears to his eyes, and when, twenty years after they had parted, he saw her again in Hollywood, he very nearly fell in love all over again with that imagined figure.

Thus, he fell in love; tentatively, as if he understood the consequences of complete commitment, he focused his imagination on her as he was to do finally with Zelda a few years later. He went back to college to write Ginevra at Westover enormous daily letters full of the touching incoherence of young lovers. “… Oh, it’s so hard to write you what I really feel when I think about you so much; you’ve gotten to mean to me a dream that I can’t put on paper any more…”

At Princeton his main concern was the clubs. At midyears he managed to pass everything except chemistry, and in March he went triumphantly into Cottage Club as one of the important men in its section, having turned down bids from Cap and Gown, Quadrangle, and Cannon. Cottage represented the type of social success Fitzgerald had dreamed of; Walker Ellis, with his personal charm, his apparently effortless embodiment of all the qualities of elegance and superiority which were the Princeton ideal, was the president of Cottage:it was the logical climax to Fitzgerald’s social career. Years later he wrote a friend he was trying to advise for her son’s sake that “though I might have been more comfortable in Quadrangle, for instance, where there were lots of literary minded boys, I was never sorry about my choice.” At the section party he passed out cold for the first time in his life.

In many ways this was one of the happiest times in his whole life. On February twenty-sixth he had been elected secretary of the Triangle and he began to look forward to being the club’s president in his senior year with a confidence which—except for his disregard of the Gargoyle—was justified. In May he was elected to the editorial board of The Tiger. He anticipated election to the Senior Council, that most select gathering of the leaders of the senior class. He was in love and on the whole happy about it; there was one wonderful moment in early June when he met Ginevra in New York. They went to Nobody Home and to the Midnight Frolic. The glittering urban splendor of a metropolitan evening was the perfect setting for Ginevra and he always remembered how “for one night… she made luminous the Ritz Roof on a brief passage through [New York].” He was also beginning to make his way among the serious writers; that occasion described in Wilson’s poem on which he had brought “the shy little scholar of Holder Court” his first contribution for the Nassau Lit, “Shadow Laurels,” had taken place and before the spring was out he had appeared twice in the Lit. He was happy among his friends at Cottage, and they topped off a spring of easy, lazy gaiety with an epic visit to Asbury Park which Fitzgerald duly recorded in This Side of Paradise. Because he was successful and confident of the future, he was at ease about everything. Consequently he was unmoved by the first faint signals of disaster which could be seen in his term-end report. Again he failed three subjects; he had taken in the first term alone more than the forty-nine cuts allowed in any two successive terms. Moreover, the ebullientdelight he always took in his own success had brought on his old habit of talking too much about himself—it was only when he verbalized his experience that it seemed completely real to him—to such an extent that even his old friends grew impatient with him. One of them sent him an “Ode to Himself, by F. S. F.”:

I can pull off a line of sob-stuff

I’m a typical Parlor Snake

At cards I’m a regular devil

When there’s anything much at stake.

My motto is “I should worry”

And before I stop I’ll say—

I’m a peach of an ‘all ‘round’ fellow

I’m Perfect in Every Way!

Next chapter 3

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).