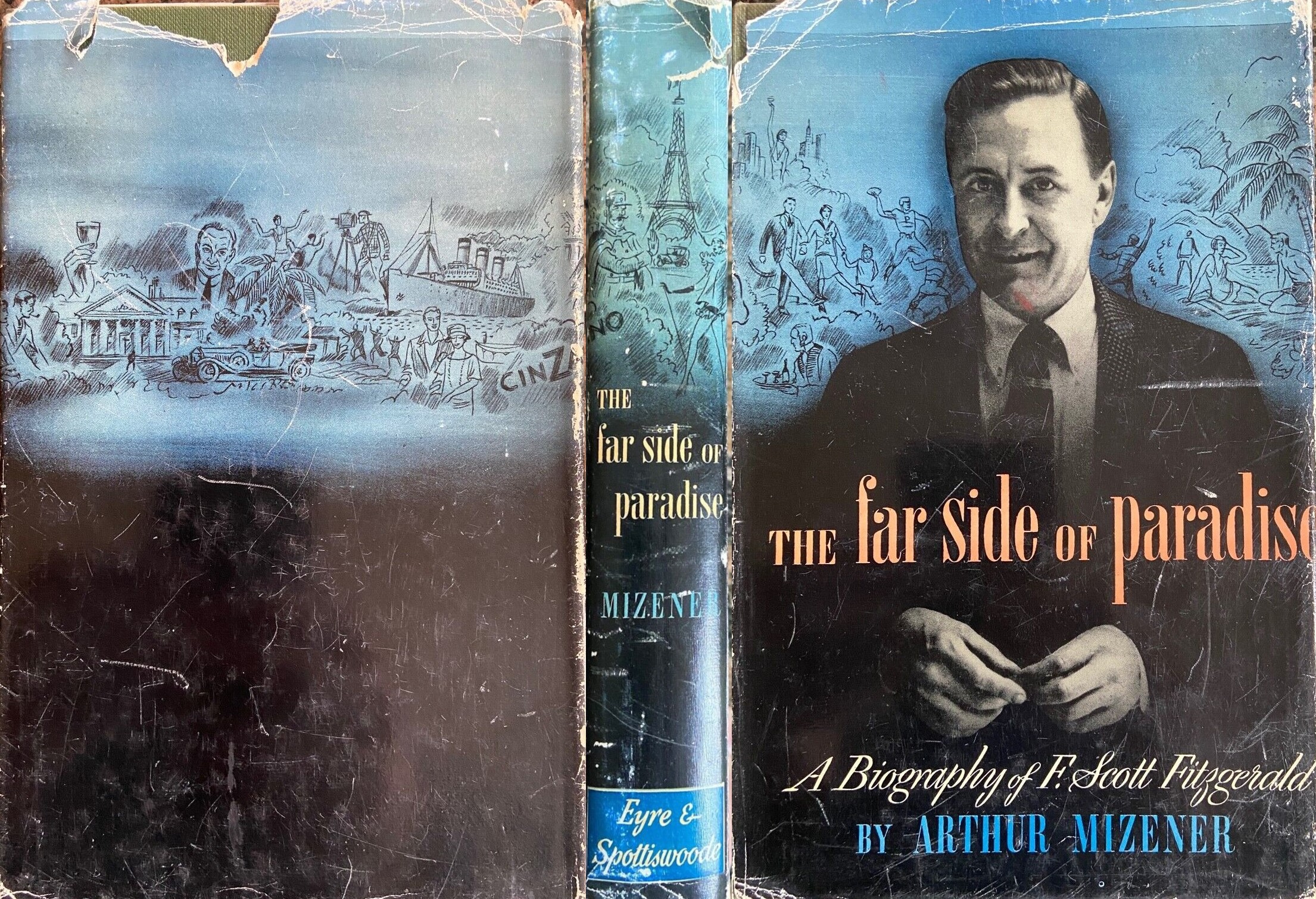

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter III

During the summer vacation he went west to visit his old friend Sap Donahoe at the Donahoe’s ranch near White Sulphur Springs, Montana. This visit provided the background for “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz.” While he was there he played cowboy in a Stetson, gauntlets and puttees, won fifty dollars at poker and on one occasion got drunk and climbed on a table to sing to the amused cowmen of White Sulphur Springs a song called “Won’t You Come Up.” He was not hearing from Ginevra, but his anxiety was somewhat relieved when he was told that his chief rival was “poor as a church mouse.”

In the fall he returned to Princeton ready to go on to the climactic triumphs of his undergraduate career. As always, however, when he was most full of confidence, the enemy struck; he flunked make-up examinations in Latin and chemistry, and he had one of those familiar conferences with the Committee on Non-Athletic Organizations and found himself ineligible. The situation was more serious now; his academic deficit had been accumulating for two years and this was the year for the crucial elections, the final rewards of three years of labor in the Triangle Club and on The Tiger (His election to the editorial board of The Tiger was announced in the issue of June, 1915; his name appeared on the masthead in the September issue and then was dropped). Still, though he had moments of despair, the situation was not yet irretrievable. There was Ginevra at Westover and they dined happily at the Elton in Waterbury after the Yale-Princeton game atNew Haven in October; he worked hard as the Triangle’s secretary, coaching his friends in their parts as a substitute for playing a part himself and doing much of the organizing and directing of the show while President Heyniger played football; he was secretary of the Bicker Committee in Cottage. What was in the sequel the most ironic event of the fall occurred when, in October, the Triangle had a series of photographs made of him as a Show Girl; these photographs were widely used for publicity over such captions as “Considered the Most Beautiful ’show Girl’ in the Princeton Triangle Club’s New Musical Play ‘The Evil Eye.’…” But Fitzgerald was of course never in the show.

In November he went to the infirmary with a high fever, got out after a week or so, and then had to return. His trouble was diagnosed at the time as malaria, which was more or less endemic at that time in Princeton, with its swamps and mosquitoes and its Negro slums down Witherspoon Street. When, in 1929, he had what subsequently proved to have been a tubercular hemorrhage, and later investigations showed the scars of even earlier attacks, he decided that this malaria had been tuberculosis. But since there is evidence of a mild attack of tuberculosis in 1919 also, there is little reason to suppose that there was anything more the matter with him than the malaria which he certainly had. His illness was perfectly real, but it also gave him an opportunity to leave college for a respectable reason at a time when the odds on his flunking out at midyears were prohibitive. His plan was to drop out for the rest of the year and to return the next September to start his junior year over again. On November 28 he attended his last class of the year therefore and departed for St. Paul. Still trying to save something from the wreckage of his social career, he persuaded Dean McClenahan to write him an official statement that “Mr. F. Scott Fitzgerald withdrew from Princeton voluntarily… because of ill-health and that he was fully at liberty, at that time, to go on with his class, ifhis health had permitted.” “Dear Mr. Fitzgerald,” said the Dean’s covering letter, “This is for your sensitive feelings. I hope you will find it soothing.” “Almost my final memory before I left,” Fitzgerald wrote later, “was of writing a last lyric on that year’s Triangle production while in bed in the infirmary with a high fever.”

But the career was beyond redemption. “… it took them,” he said twenty-five years later, still hating vigorously the malicious and impersonal “them,” “four months to take it all away from me—stripped of every office and on probation—the phrase was [it was written on his heart like Philip and Calais] ‘ineligible for extra-curricular activities.’“ In February he came on to Princeton for a visit; both the club elections and the Triangle elections were impending. But there was nothing to be done. “To me,” he wrote twenty years later, “college would never be the same. There were to be no badges of pride, no medals, after all. It seemed on one March afternoon that I had lost every single thing I wanted—and that night was the first time that I hunted down the spectre of womanhood that, for a little while, makes everything else seem unimportant.”

For all the trivial objective content of the experience, this was one of the great blows of his life. He had committed himself imaginatively to this world—or had had his imagination committed to it by circumstances—and the occasion’s value was determined for him by what his imagination had made of it. He brought with him to Princeton for exorcism the ghosts of all his past failures. To have succeeded at Princeton would have been to triumph in a world so superior to the Middle West that he could have taken the Middle West for granted. And he had succeeded at Princeton; he had made Cottage, had every reason to believe he would be president of the Triangle, an editor of The Tiger, perhaps even a member of the Senior Council. Then, just as he was about to receive these tangible evidences of his success and at last feel at easein a world which satisfied the needs of his nature, the Gargoyle, with his gift for perfectly timed malice, struck, and for the third time he was defeated. Had he had his rewards, his badges and medals, he would no doubt quickly have seen them for what they were. But he did not get them, so that all his life he remembered the deprivation and could not get out of his mind an extravagant sense of the value of these medals or a feeling that somehow he had never quite known what it was to be a Princeton man, had not penetrated to the innermost sanctum which his imagination dimly conceived, was still only a very good imitation of a man accepted and at ease in the aristocratic world. “… a typical gesture on my part,” he wrote John O’Hara twenty years later, “would have been, for being at Princeon and belonging to one of its snootiest clubs, I would be capable of going to Podunk on a visit and being absolutely booed and overawed by its social system, not from timidity but because of some inner necessity of starting my life and my self justification over again at scratch in whatever new environment I may be thrown.” Like Dick Diver, the hero of Tender Is the Night, at Yale, he went “through [Princeton] almost succeeding but not quite”; instead of removing his sense of social insecurity, this experience fixed it permanently. “I was always trying to be one of them!” as he told James Drawbell years later. “That’s worse than being nothing at all!”

For the young man who set it down that “if I couldn’t be perfect I wouldn’t be anything” this “not quite” was worse than no success at all. That all this disaster should have resulted from the Gargoyle’s suddenly turning on him again seemed to him the grossest kind of injustice. Eventually he was going to describe this period in his Ledger as “A year of terrible disappointments & the end of all college dreams. Everything bad in it was my own fault.” Even when he wrote This Side of Paradise he had Monsignor Darcy chide Amory over his inability to “do the next thing” and described Amory’s failure by saying: “The fundamental Amory, idle, imaginative, rebellious, had been nearly snowed under. He had conformed, he had succeeded, but as his imagination was neither satisfied nor grasped by his own success, he had listlessly, half-accidentally chucked the whole thing and become again… the fundamental Amory.” But when, five years later, President Hibben wrote him a letter of mild remonstrance at the impression given by This Side of Paradise “that our young men are merely living for four years in a country club and spending their lives wholly in a spirit of calculation and snobbery,” Fitzgerald was still so angry at the Gargoyle’s outrageous injustice that he replied:

[This Side of Paradise] was a book written with the bitterness of my discovery that I had spent several years trying to fit in with a curriculum that is after all made for the average student. After the curriculum had tied me up, taken away the honors I’d wanted, bent my nose over a chemistry book and said, “No fun, no activities, no offices, no Triangle trips

—no, not even a diploma “if you can’t do chemistry”—

—after that I retired.

(The John Grier Hibben Papers, Princeton University Library. Fitzgerald's concentration on chemistry in this letter is not quite fair to Princeton. While he was there he failed a third of the courses he took and maintained a fourth-group (D—) average in the rest).

At moments all the rest of his life this feeling of helpless rage—not really at others so much as at life, for having refused him what he had earned—would come back. In 1940, when he finally ran across Bishop’s article, “The Missing All,” and read its quite truthful assertions that he was “dropped from the class [of 1917]” and that “he had an ailment, which served as an excuse for his departure,” he was in a rage. “I left on a stretcher in November—you don’t flunk out in November,” he wrote Hemingway. At the same time he was writing his daughter: “I wore myself out on a musical comedy there [at Princeton] for which I wrote book and lyrics, organized and mostly directed while the president played football. Result: I slipped way back in my work, got T. B., lost a year in college—and, irony of ironies, because of [a] scholastic slip I wasn’t allowed to take the presidency of the Triangle.” “…no Achilles heel ever toughened by itself,” as he remarked to her on another occasion. “It just gets more and more vulnerable.” [It was President Walker Ellis, 1915, who took credit for Fitzgerald’s book for Fie! Fie! Fi-Fi!; it was President C. L. Heyniger, 1916, who played football and left Fitzgerald to organize and direct The Evil Eye].

His friends on the Lit summed up his career with less sympathy:

I was always clever enough

To make the clever upper classmen notice me;

I could make one poem by Browning,

One play by Shaw,

And part of a novel by Meredith

Go further than most people

Could do with the reading of years;

And I could always be cynically amusing at the expense

Of those who were cleverer than I

And from whom I borrowed freely,

But whose cleverness

Was not of the kind that is effective

In the February of sophomore year.…

No doubt by senior year

I would have been on every committee in college,

But I made one slip:

I flunked out in the middle of junior year.

[These lines appear in 'Gossip,' a department which, according to the index, was written for this issue by John Peale Bishop and Edmund Wilson, Jr. Five years later, Fitzgerald, obviously quoting from memory, ascribed 11. 3-6 of the poem to Wilson in an interview by Roy McCardell published in the Morning Telegram (Clipping in Album III). Mr. Wilson's own impression is 'that John first wrote the vers libre piece in the Gossip and then I revised it and probably wrote the lines Scott quoted.' (Edmund Wilson to Arthur Mizener, October 14, 1949.)].

The next eight months were unhappy and aimless ones for him. He sat in the audience when “The Evil Eye” played in St. Paul; he had mumps; he occasionally got drunk. In February he put on his Show Girl make-up and went to a Psi U dance at the University of Minnesota with his old friend Gus Schurmeier as escort. He spent the evening casually asking for cigarettes in the middle of the dance floor and absent-mindedly drawing a small vanity case from the top of a blue stocking. This practical joke made all the papers, but it was an inadequate substitute for the flowers he had looked forward to as “the Most Beautiful ’show Girl’ in the Triangle Club.” [“At the Chicago performance of ‘The Evil Eye,’ “said The Daily Princetonian on January 7, 1916, “300 young ladies occupied the front rows of the house and following the show, they stood up, gave the Princeton locomotive and tossed their bouquets at the cast and chorus.” “They sent flowers too,” Fitzgerald wrote his daughter twenty-five years later of his attack of malaria, “—but not to the footlights, where I expected them—only to the infirmary. “]In March he was preoccupied with Ginevra’s leaving Westover after Miss Hillard, the headmistress, had accused her of scandalous conduct and had later retracted the charge (See “A Woman with a Past,” which gives a fairly accurate account of the affair). The play he wrote for the Triangle that spring was rejected. In August he paid Ginevra an unhappy visit at Lake Forest. “Poor boys,” someone told him, “shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls.”

In September he was back at Princeton to begin over again in his stubborn and courageous way. He was still ineligible, but Paul Nelson, who had been elected to the presidency of the Triangle Club which he had expected to get, suggested there was still hope for him despite the rejection of his book, and he set to work once more to write the songs for the show; once more the Show Girl pictures were got out and printed in the newspapers, though he was not to be in this new show either. He wrote endlessly for The Tiger despite his lack of any official connection with it and conceived and wrote most of an issue of the Nassau Lit which burlesqued Cosmopolitan. Ginevra came down for the Yale game, but they were quarreling now and when they met again in January, she was no longer interested; they quarreled, so far as she was concerned, finally. (“I have destroyed your letters,” she wrote him that summer in reply to a request from him, “… I’m sorry you think that I would hold them up to you as I never did think they meant anything.”)

His interests were gradually shifting from the social to the intellectual world. He began to see more of Bishop and John Biggs, who in March succeeded Bishop as editor of the Lit. He became friendly with David Bruce and with Henry Strater, who read Tolstoi and Edward Carpenter and WaltWhitman and seemed to take them quite seriously. These two, together with Richard Cleveland, the president’s son, led a famous sophomore rebellion against the clubs in the spring, a rebellion in which ninety sophomores bound themselves “not to join any elective eating club while members of Princeton University,” and, with the sympathy of the Princetonian, whose editorial editor, Alec McKaig, supported them boldly, they managed to reduce by twenty-five per cent the number of sophomores joining clubs and might have worked a permanent change in the system had not the interruption of the war destroyed their work.

Fitzgerald was fascinated by Strater; Strater seemed to be utterly unaffected by social disapproval, going about the business of doing what he thought right without regard for prestige; he seemed to see better than anyone the absurdity of the defenders of the clubs who solemnly accused him of trying to bring about a situation in which “the entire College dined in an atmosphere of Utopian socialistic love.” He suggested to Fitzgerald a new conception of superiority, a conception of moral and intellectual integrity which Strater’s dramatic assertion made colorful and appealing to him, especially when Strater, sticking firmly to his Tolstoian position, came out as a pacifist in the face of our declaration of war. Fitzgerald never wholly gave in to Strater, but he listened to him, often all night, and took out his puzzlement by contributing liberally to an issue of The Tiger which satirized impartially both the clubs and the reformers. He was especially amenable to the appeal of Strater’s kind of distinction because, with the failure of his social career, he had begun to write for the first time in his life with the mature intention of realizing and evaluating his experience.

During the previous term, while he had been out of college, he had written “The Spire and the Gargoyle,” which is, for all its naïveté, an attempt to deal with his own failure. Writing made him realize a little how much he had been deprived of by the desire to conform, and until after he had written TheBeautiful and Damned he thought of Strater as the “greatest influence in his writing.” “My idealism,” he said, “flickered out with Henry Strater’s anticlub movement at Princeton.”

In February he went to New York to see Wilson in his Eighth Street apartment and thought Wilson had found the ideal man’s world, at once “released… from all undergraduate taboos” and yet “mellow and safe, a finer distillation of all that I had come to love at Princeton.” He had begun to read voraciously in Tarkington, Shaw, Wells, Butler, and, above all, Compton Mackenzie. He was enchanted by Youth’s Encounter and Sinister Street and began a period of seeing himself as Michael Fane and all his friends as appropriate subsidiary figures. Wilson and his other New York friends fitted in admirably, as did Fay, who took him to dine in suave splendor at the Lafayette and got confused in Fitzgerald’s exuberant imagination with Mr. Viner. Thus with his imagination full of the romance of Sinister Street—so that, seeing a man disappear silently into a doorway in Greenwich Village one night he had an almost physical sense of the pressure of evil—and with his head “ringing with the meters of Swinburne [and, he ought to have added, Tennyson] and the matters of Rupert Brooke,” he plunged into being a writer. He deluged the Nassau Lit with his work and before he was through they had published nine poems, five reviews, and eight short stories.

With this shift, he completed for the first time what was to be the characteristic pattern of his relation to his experience. In one of the best articles written at the time of The Crack-Up’s publication, Malcolm Cowley noticed what he called Fitzgerald’s “double vision.” “It was as if,” he said, “all his novels described a big dance to which he had taken… the prettiest girl… and as if at the same time he stood outside the ballroom, a little Midwestern boy with his nose to the glass, wondering how much the tickets cost and who paid for the music.”

This is an important insight for an understanding of Fitzgerald the talented novelist. His nature was divided. Partly he was an enthusiastic, romantic young man. Partly he was what he called himself in the “General Plan” for Tender Is the Night, “a spoiled priest.” This division shows itself in nearly every aspect of his life. The romantic young man was full of confidence about his own ability and the world’s friendliness; the spoiled priest distrusted both himself and the world. The romantic young man wanted to participate in life and took delight in spending himself and his money without counting the cost (“All big men have spent money freely,” he wrote his mother when she tried to caution him in 1930, “I hate avarice or even caution”); but the spoiled priest, shocked by debt and fearing the spiritual exhaustion Fitzgerald was later to call “Emotional Bankruptcy,” wanted to stand aside and study life. The spoiled priest compared the romantic young man—as his author compared Gatsby—to Trimalchio, the rich and vulgar upstart in Petronius’ Satyricon.

But the talented novelist, whose books Fitzgerald sometimes read “for advice” (“How much,” he said, “I know sometimes—how little at others”) would not have existed without them both. All his best work is a product of the tension between these two sides of his nature, of his ability to hold in balance the impulses “to achieve and to enjoy, to be prodigal and open-hearted, and yet ambitious and wise, to be strong and self-controlled, yet to miss nothing—to do and yet to symbolize.” Not until 1936 did he lose faith in his ability to realize in his personal life what he called “the old dream of being an entire man in the Goethe-Byron-Shaw tradition, with an opulent American touch, a sort of combination of J. P. Morgan, Topham Beauclerk and St. Francis of Assisi…” He never lost his conviction that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

If Fitzgerald’s imagination owes its force and penetrationto the spoiled priest, however, it was the kind which works successfully only when it has personal experience to deal with; Fitzgerald was a romantic in the sense that for him “the divine,” as Hulme put it, “is life at its intensest.” “Taking things hard—from Genevra to Joe Mank—“he said, remembering his whole life, from his first love (Ginevra King) to his last battle (with Joseph Mankiewicz, the Hollywood producer) to preserve the integrity of his work: “That’s the stamp that goes into my books so that people can read it blind like brail.” Understanding was for him the awareness of a constellation of feelings and of the objects to which they attached themselves in a moment of actual experience. “After all,” as he said, “any given moment has its value; it can be questioned in the light of after-events, but the moment remains. The young princes in velvet gathered in lovely domesticity around the queen amid the hush of rich draperies may presently grow up to be Pedro the Cruel or Charles the Mad, but the moment of beauty was there.” Thus the direct experience of the romantic young man who plunged eagerly and unwarily into the life about him provided the novelist with his material.

This material the spoiled priest struggled throughout Fitzgerald’s life to understand. When he was young this struggle sometimes gave Fitzgerald an almost priggish air. Once, for instance, when he was an undergraduate he watched a friend leave a group of classmates on Nassau Street to pursue a young lady. After a long silence, he said: “That’s one thing Fitzgerald has never done!” This attitude gave his early critics their most obvious target. “… a chorus girl named Axia,” said Heywood Broun in his review of This Side of Paradise, “laid her blond head on Amory’s shoulder and the youth immediately rushed away in a frenzy of terror and suffered from hallucinations for forty-eight hours. The explanation was hidden from us. It did not sound altogether characteristic of Princeton.” This moral earnestness was alsopartly responsible for Fitzgerald’s changing his title from The Romantic Egotist to This Side of Paradise: “Well, this side of Paradise!… There’s little comfort in the wise.” Rupert Brooke’s lines in “Tiare Tahiti” imply more than “we glamorous young people live practically in heaven”; they also mean “the world is very imperfect and the prudent wisdom of the old is perhaps no better than the imprudent sincerity of the young.”

Ernest Boyd was, for all his fancy writing, observing shrewdly when he said of Fitzgerald in 1924: “There are still venial and mortal sins in his calendar, and … his Catholic heaven is not so far away that he can be misled into mistaking the shoddy dreams of a radical millennium as a substitute for Paradise…. His confessions, if he ever writes any, will make the reader envy his transgressions, for they will be permeated by the conviction of sin, which is much happier than the conviction that the way to Utopia is paved with adultery.” At the end of his life Fitzgerald himself wrote his daughter: “Sometimes I wish I had gone along with [Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart and that gang], but I guess I am too much a moralist at heart, and really want to preach at people in some acceptable form, rather than to entertain.”

These are the forces which constitute what he called “luxuriance of emotion under strict discipline.” They are logically contradictory impulses, but much of the time, and always when he was at his best, they functioned together in Fitzgerald. When his child was born in 1921, his emotional involvement with Zelda in her suffering was intense; he was, as the friend who waited with him at the hospital said, all prospective fathers rolled into one. At the same time he had his notebook out—“I might be able to use this”—and was taking down everything Zelda said. What he took down was: “Oh God, goofo I’m drunk. Mark Twain. Isn’t she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it’s beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.” When Daisy, the heroine of The Great Gatsby,is first showing the soft spot in her nature, what Nick calls her “basic insincerity,” the talented novelist was indeed able to use this.

“Oh yes.” She looked at me absently. “Listen, Nick; let me tell you what I said when [the baby] was born. Would you like to hear?”

“Very much.”

“It’ll show you how I’ve gotten to feel about—things. Well, she was less than an hour old and Tom was God knows where. I woke up out of the ether with an utterly abandoned feeling, and asked the nurse right away if it was . a boy or a girl. She told me it was a girl, and so I turned my head away and wept. ‘All right,’ I said, ‘I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool….’”

The instant her voice broke off, ceasing to compel my attention, my belief, I felt the basic insincerity of what she had said…

This act of uninvolved understanding at a moment of maximum involvement is of a piece with hundreds of others, from the compassionate but devastating portrait of Ring Lardner which he used as a foundation for the character of Abe North in Tender Is the Night to the many frank and disapproving portraits he made of himself in various guises in his fiction. You always wonder, as Glenway Wescott wondered of “The Crack-Up,” “if he himself knew how much he was confessing.” But of course he did. “You’ve got to sell your heart,” he wrote a young writer, trying to explain what he did. “… In ‘This Side of Paradise’ I wrote about a love affair that was still bleeding as fresh as the skin wound on a haemophile.” (He said much the same thing to James Boyd: 'I have just emerged not totally unscathed, I'm afraid, from a short violent love affair. . . . maybe some day I'll get a chapter out of it. God, what a hell of a profession to be a writer. One is one simply because one can't help it' (to James Boyd, August, 1935; The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Andrew Turnbull, New York, 1963 , pp. 528-529). It was only one example from a lifetime’s accumulation.

The stories he wrote during this period of seeking to understand his life at Princeton are, apart from “The Spire and the Gargoyle” and one war story, about Ginevra. Like all his deeply felt experiences, this one would not let him rest, and he was struggling to understand what he and Ginevra had been and why they had acted as they had. Each of the stories has a conventional, even banal framework, which is often very naively handled—the young lover who climbs the rain pipe to talk to his girl, the alcoholic but indefinably charming bohemian uncle with a secret sorrow—but at the heart of each is a version of himself and Ginevra, genuine, alive, and, at each reimagining, more fully understood.

All through this spring of 1917 a preoccupation with the war had been growing at Princeton. A large delegation of undergraduates had gone off to join the mosquito fleet; another was, with the assistance of experienced military men like Professor Robert Root of the English Department, drilling energetically on the campus. With the immediate support of Strater’s pacifism and John Biggs’ common sense, Fitzgerald took little part in this excitement. He never did participate in the rotarian kind of war hysteria—“wine-bibbers of patriotism,” he called such people, “which, of course, I think is the biggest rot in the world.” He had his own pose, built partly out of Rupert Brooke and partly out of what he called “the short, swift chain of the Princeton intellectuals, Brooke’s clothes, clean ears, and, withall, a lack of mental prigishness… Whipple, Wilson, Bishop, Fitzgerald…” Its form was: “This insolent war has carried off Stuart Wolcott in France, as you may know and really is beginning to irritate me—but the maudlin sentiment of most people is still the spear in my side. In everything except my romantic Chestertonian orthodoxy I still agree with the early Wells on human nature and the ‘no hope for Tono Bungay’ theory.” The two sources of the attitude are interesting, since Fitzgerald’s attitude, deepened by their experience of the war and of the activities of the Palmers and the Volsteads and the Doughertys, was to emerge in the twenties as the younger generation’s.

Fitzgerald went on, with enforced calm noting the names of classmates he had admired who were already being killed in France during the winter and spring of 1916-1917 and trying to decide whether to enlist in the air force or the infantry. In June he visited Fay at Deal and heard the first of a scheme which was to occupy him for some time. The scheme was surrounded by a great deal of mystification, but on some authority—there are hints in Fay’s letters that it was the very highest—Fay was going to Russia, ostensibly as the head of a Red Cross mission but actually to see what he could do for the Roman Church in Russia during the disturbance of the Kerensky revolution. His plan was to take Fitzgerald along, in the guise of a Red Cross lieutenant, as his confidential assistant. The boyish, E. Phillips Oppenheim air with which he and Fitzgerald managed to invest the affair can be seen from Fay’s letters:

Now, in the eyes of the world, we are a Red Cross Commission sent out to report on the work of the Red Cross, and especially on the State of the civil population, and that is all I can say. But I will tell you this, the State Department is writing to our ambassador in Russia and Japan, the British Foreign Office is writing…. Moreover I am taking letters from Eminence to the Catholic Bishops….

As soon as you have read this letter and shown it at home, burn it.

He and Fay had another conspiratorial conference in Washington late in the month to discuss costs—they were to pay their own way—and the important matter of the uniform (they agreed that only Wetzel could do the case justice). Fitzgerald then went on to spend a literary month with Bishop at his home in Charles Town, West Virgina, where he “wrote a terrific lot of poetry mostly under the Masefield-Brooke influence.” One of these outpourings, entitled “The Way to Purgation,” was sold to Poet Lore in the fall; it was the first piece of writing he ever sold, though Poet Lore never printed it. Poet Lore’s letter of acceptance is in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Scrapbook; he had sent Wilson the poem earlier in the fall (see The Crack-Up, p. 249), and he submitted it two years later to Professor Morris Croll for inclusion in A Book of Princeton Verse II (1919), where it was again not printed.

Late in July he was back in St. Paul, where he went out to Fort Snelling and took the necessary examinations for a provisional appointment as a second lieutenant in the regular army. At the same time he was getting his passport for Japan and Russia to go with Fay. Early in September there came a hasty letter from Fay in Washington: “We can not go to Russia because of the new Revolution…. But there is another reason which is that you and I are to be sent to Rome. Do not breathe a word of this and burn this letter. … I cannot put details on paper.” This turned out to be a mission from Cardinal Gibbons to the Pope to lay before him the American Catholic attitude toward the war, “which is most loyal—barring the Sien-Fien—40% of Pershing’s army are Irish Catholics,” as Fitzgerald summed it up. But this scheme, too, hung fire (Fay finally got to Rome the following February); he had further consultations with Fay at Deal Beach, but there was nothing to do but return to Princeton for his senior year and wait restlessly for his commission. He roomed with John Biggs who, like him, was on The Tiger and the Lit. Together they sometimes produced whole issues of The Tiger between darkness and dawn and wrote a great deal of the Lit.

His commission was finally issued on October 26. His first move on receiving it was to sign the Oath (“My pay started the day I signed the Oath of Allegiance and sent it back which was yesterday”); his second to go up to New York, to Brooks Brothers, and order his uniforms. Presently his orders came and he prepared to depart for Fort Leavenworth on November 20. He maintained the proper attitude, writing his mother:

About the army please lets not have either tragedy or Heroics because they are equeally distastful to me. I went into this perfectly cold bloodedly and dont sympathize with the

“Give my son to country” ect

or ect

“Hero stuff” ect

because I just went and purely for social reasons. If you want to pray, pray for my soul and not that I wont get killed—the last doesn’t seem to matter particularly and if you are a good Catholic the first ought to.

To a profound pessimist about life, being in danger is not depressing. I have never been more cheerful.

This letter is colored by his special feelings about his mother: he was afraid that she might make some ill-timed assertion of conventional patriotism in St. Paul and that would hurt him because he suffered from his mother’s being foolish almost as much as from his own being so. He had to discipline her. “I could now be sympathetic to Mother,” he had written the year before, “but she reacts too quickly.” Yet the attitude this letter expresses represents, in spite of its affectations, motives that were very real in Fitzgerald. “Updike from Oxford or Harvard,” he wrote his cousin Ceci, “says ‘I die for England’ or ‘I die for America’—not me I’m too Irish for that—I may get killed for America—but I’m going to die for myself.” Moreover, for all his dislike of conventions patriotism he was appealed to by the romantic idea of the allant individual confronting and dominating danger and death. His. not getting overseas and into action came gradually to seem to him a great deprivation. “It was as if, when he came later to read books about it,” as Edmund Wilson has said, “he decided that he had been greatly to blame for not having had any real idea of what had been going on at that time, and he suddenly produced his old trench helmet which had never seen the shores of France and hung it up in his bedroom at Wilmington and would surprise his visitors there by showing them, as if it were a revelation, a book of pictures of horribly mutilated soldiers.” (As part of her education he required his eleven-year-olddaughter to look these pictures over at La Paix in 1932, and the book was still in his library when he died.)

Nor was the loss of a romantic occasion the only loss Fitzgerald imagined; the war had a curiously social quality for him too. Missing out on it was for him a little like his never having, as an undergraduate, got into the inner sanctum of the Big Men at Princeton.

“God damn it to hell,” he once said, “I never got over there. I can’t tell you how I wanted to get over. I wanted to belong to what every other bastard belonged to: the greatest club in history. And I was barred from that too. They kept me out of it. … Oh, God, I’ve never made it in anything!”

This feeling of deprivation, with its curious mixture of romantic and social frustrations, is dramatized in the story he wrote about it twenty years later called “‘I Didn’t Get Over.’” “‘I Didn’t Get Over’” is the story of Captain Hibbing, who is snubbed during a training exercise by an officer named Abe Danzer who had been a prominent figure when they had been at college together. Hibbing is thrown off by this snub, loses his head, and asserts his authority by forcing the troops to cross a river in a leaky ferry which sinks with the loss of several men. All the heroism of the story belongs to Abe Danzer, but Fitzgerald identifies himself with Hibbing, who was thrown off by Danzer’s snubbing him and acted badly as a consequence, just as Fitzgerald sometimes did in similar circumstances. The experience Hibbing has to tell about is far more dramatic than anything that happened to those who did get over and “spent most of [the time] guarding prisoners at Brest.” But it was not, as Hibbing put it, “the big time.” Training camp was a hopelessly inadequate setting for the heroism Fitzgerald had imagined. There was a barge sinking during a practice crossing of the Talapoosa River while Fitzgerald was in training. There was also an occasion when a propellant charge failed to go off and a fused shell stuck in a Stokes Mortar. The Director of the School of Arms, Major Dana Palmer, picked up the mortar and swung it so that the shell was thrown far enough away to explode without injuring anyone (Major Dana Palmer to Arthur Mizener, February 11, 1951).

His departure from Princeton was, he thought, the end ofyouth, the end of experiments with life and fresh starts undertaken with easy confidence that there was plenty of time, the end of the period when one is irretrievably committed to nothing. These were the things he meant when he talked about youth, when he said at the age of twenty-one, “God! how I miss my youth—that’s only relative of course but already lines are beginning to coarsen in other people and that’s the sure sign.” There were many social influences to encourage this attitude in the twenties—the revolt of the “Younger Generation,” the heritage from the hedonism of the Nineties. But Fitzgerald’s feelings about youth went much deeper than that; because his commitment to any experience was always unguarded, he could appreciate, as few people ever have, his youth, which had no commitments of invested vitality, no past, no unredeemable times “lost, spent, gone.” Though he loved experience, he hated the indelible “marks of weakness, marks of woe” it left. Even through the pose of the young man off to the wars and writing to a pretty cousin, you can feel this conviction: “On the whole I’m having a fairly good time—but it looks as if the youth of me and my generation ends sometime during the present year, rather summarily—If we ever get back, and I don’t particularly care, we’ll be rather aged—in the worst way. After all life hasn’t much to offer except youth and… every man I’ve met who’s been to war, that is this war, seems to have lost youth and faith in man…”

Fitzgerald’s directness in asserting these feelings made it easy to misunderstand him. “You put so damned much value on youth,” Hemingway wrote him nearly twenty years later, “it seems to me that you confused growing up with growing old….” But it was not, of course, a desire to avoid maturity that determined Fitzgerald’s feeling. What he wanted to do was to keep his emotional capital intact, and this desire was in turn the result of his fear of bad investment rather than of any timorousness in the face of experience. He hadbegun to understand very early in life how dependent he was on emotional energy and to be disturbed by its extravagant expenditure. “I was always,” he said later of his young manhood, “saving or being saved—in a single morning I would go through the emotions ascribable to Wellington at Waterloo.” This ability to care intensely was his great personal charm; everyone you talk to who knew him as a young man will try to make you understand that charm. They will laugh at their memory of his unguarded eagerness and excitement over parties and his dashing but inaccurate dancing—he could not carry a tune and he had a very uncertain sense of rhythm. But like Jay Gatsby’s, his life was modeled on “his Platonic conception of himself.” No one ever remembers except with a certain envy the way he could say to the girl he was dancing with, ”My God, you’re beautiful! You’re the most beautiful girl I know!”—and mean every word of it.

But he also knew how extravagant this expenditure of vitality was. Later in his life he would work out a theory of what he called “Emotional Bankruptcy”; it is the most pervasive idea he ever had and it derives directly from his own knowledge of himself. Neither Tender Is the Night nor The Last Tycoon makes very good sense unless you realize how deeply embedded in them this idea is. Even at the age of twenty-one he had the essentials of it worked out. He summed them up in a poem called “Princeton—The Last Day” which, if it is still borrowing heavily for its style, states accurately his feeling that at this point in his life he was leaving for good the endless pause of youth.

No more to wait the twilight of the moon

In this sequestrated vale of star and spire;

For one, eternal morning of desire

Passes to time and earthy afternoon.

Here, Heracletus, did you build of fire

And changing stuffs your prophecy far hurled

Down the dead years…

Just before he left Princeton, he brought Dean Gauss the manuscript of a novel. He wanted Dean Gauss to recommend the book to his publisher, Scribner’s. Gauss, after reading it, told Fitzgerald frankly that he could not do so. Fitzgerald argued that he would probably be killed in the war and wanted it published. This conviction had taken a strong hold on his imagination; as late as 1923 he was telling a reporter that he had been “certain all the young people were going to be killed in the war and he wanted to put on paper a record of the strange life they had led in their time.” Dean Gauss finally talked him out of trying to publish. He remembers that the first part of this novel was much like the first part of This Side of Paradise, the remainder a series of unconnected anecdotes, satires, and verse about Princeton life, such as “The Spire and the Gargoyle” and the satire on Alfred Noyes’ class in This Side of Paradise.

But Fitzgerald was not through with the novel. He carried over into Officers’ Training Camp precisely the attitude he had been maintaining at Princeton. He did not fail to note, half in earnest and half ironically, that “in my right hand bunk sleeps the editor of Contemporary Verse (ex) Devereux Joseph, Harvard ‘15 and a peach—on my left side is G. C. King a Harvard crazy man who is dramatizing War and Peace; but you see I’m lucky in being well protected from the Philistines” —and, he might have added, that great mass of people who had not gone to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton. But his main preoccupation was his novel. At about the time he was showing the first version of his book to Dean Gauss, Fay, about to depart for Europe, confided Fitzgerald to Shane Leslie’s care and Fitzgerald showed Leslie his poems and later wrote him his plans for a “novel in verse.” The minute he was settled at Leavenworth, he started to rewrite his novel, at first by concealing a pad within his copy of Small Problems for Infantry and later, after he had been caught at this, by working weekends amidst the smoke and conversation and rattling of newspapers at the Officers’ Club. “I would begin work at it every Saturday afternoon at one and work like mad until midnight. Then I would work at it from six Sunday morning until six Sunday night, when I had to report back to barracks. I was thoroughly enjoying myself.” Working in this way he wrote a novel of one hundred and twenty thousand words, twenty-three chapters, of which four were in verse, “on the consecutive week-ends of three months”—that is, while he was at Fort Leavenworth; he was transferred to Camp Taylor, Kentucky, in February, 1918. It is hardly any wonder that he was remembered at Leavenworth as “a sandy-haired youngster… the world’s worst second lieutenant.”

Fitzgerald’s statement that The Romantic Egotist was completed by January is a slight exaggeration; he still had five of his twenty-three chapters to go. But in spite of being on leave that month, he got the rest finished by March, doing part of the job in Cottage Club during his leave and sending the final installment to Bishop in March. He sent the book to Leslie who, after spending ten days correcting the punctuation and grammar, sent it along to Scribner’s with a recommendation and a request that, if they did not like it, they keep it anyway so that Fitzgerald “could go to France believing his book had been accepted.” (Leslie’s letter is still in Scribner’s files. A section of ms., later incorporated into the THIS SIDE OF PARADISE ms. without change (it is the passage on p. 168 of THIS SIDE OF PARADISE) is inscribed “Completed at Cottage Club on leave, February, 1918.” It was so inscribed when Cottage, in 1933, got up a committee to collect memorabilia of famous members. Fitzgerald eventually decided to send them, instead of this page, the ms. of “Good Morning Fool!” (THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, pp. 117-19). This piece of ms., also with an inscription stating that it was completed in Cottage in 1918, now hangs in the club library). By June the book was being read by Scribner’s.

The Romantic Egotist was a very crude book, yet it was an original and striking book, too. “I don’t think you ever realized at Princeton,” he wrote Wilson while he was at work on it, “the childlike simplicity that lay behind all my petty sophistication and my lack of a real sense of honor.” À good deal of this combination of simplicity and petty sophistication was in The Romantic Egotist. But it also had Fitzgerald’s penetration and honesty. The book’s worst faults were its lack of structure and, in the early parts, of concrete particulars. “Each scene—chapter or what you will should be significant in the development either of the story or the hero’scharacter and I don’t feel that yours are,” Bishop wrote him. “You see Stephen does the things every boy does. Well and good…. But the way to get it is to have the usual thing done in an individual way. You don’t get enough into the boy’s reactions to what he does…. You see what I mean? Each incident must be carefully chosen—to bring out the typical: then ride it for all it’s worth.” But if the book had faults, it should also be remembered that a great deal of what is now This Side of Paradise, including some of the best of it, such as the chapters about Princeton and the Isabelle and Eleanor episodes, was carried over into that book with only minor revisions from The Romantic Egotist.’ [The episode of The Devil is in THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, Bk. I, chapter III; the Isabelle episode in Bk. I, chapter II; the Eleanor episode in Book II, chapter III. No complete ms. of The Romantic Egotist now exists but a ms. of five chapters - I, II, V, XII, and XIV - has been presented to the Princeton Library by Mr. Charles W. Donahoe, and several sections of the existing ms. of THIS SIDE OF PARADISE are the revised typescript of The Romantic Egotist: the original names of the characters are still decipherable where they have been inked over. The statements in the text of what The Romantic Egotist contained are based on this evidence. The Isabelle episode of course existed even earlier than The Romantic Egotist.]

In August Scribner’s returned the book to Fitzgerald with a long and encouraging letter. “… we are,” they said, “considerably influenced by the prevailing conditions, including a governmental limitation on the number of publications… but we are also influenced by certain characteristics of the novel itself.” They then went on to make a number of detailed suggestions and concluded by urging him to submit the book again. Fitzgerald attempted to meet these suggestions and returned the manuscript to Scribner’s, but at the end of October they finally rejected it. Of the editors only Perkins was really for it; both Brownell and Burlingame favored its rejection.

At the same time he had been getting on with his career as the worst second lieutenant in the army. In February he got a leave and made a flying trip east to visit Princeton. He returned to Camp Taylor, Kentucky, where he found Bishop, who showed him around Louisville and talked poetry with him into the small hours. In April he was transferred again, to Camp Gordon, Georgia, and, in June, yet again to Camp Sheridan near Montgomery, Alabama. Here, in June, he received the news that Ginevra was to be married in September.

Then one Saturday night at the country club he noticed a girl dancing with his friend Major Dana Palmer. She was young, so young that she had not put up her hair and wore the frilly sort of dress that used to be reserved for young girls. As he looked at her, he always recalled afterward, everything inside him seemed to melt. The minute the dance was over, he got hold of Major Palmer and had himself introduced to Zelda Sayre. In his precise way where emotions were concerned he noted in his Ledger that he “fell in love on the 7th” of September. Like Amory Blaine, who stopped at the door of the Knickerbocker bar to check his watch before he got drunk because Rosalind had finished with him, Fitzgerald always “wanted particularly to know the time, for something in his mind that catalogued and classified liked to chip things off cleanly.”

Next chapter 4

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).