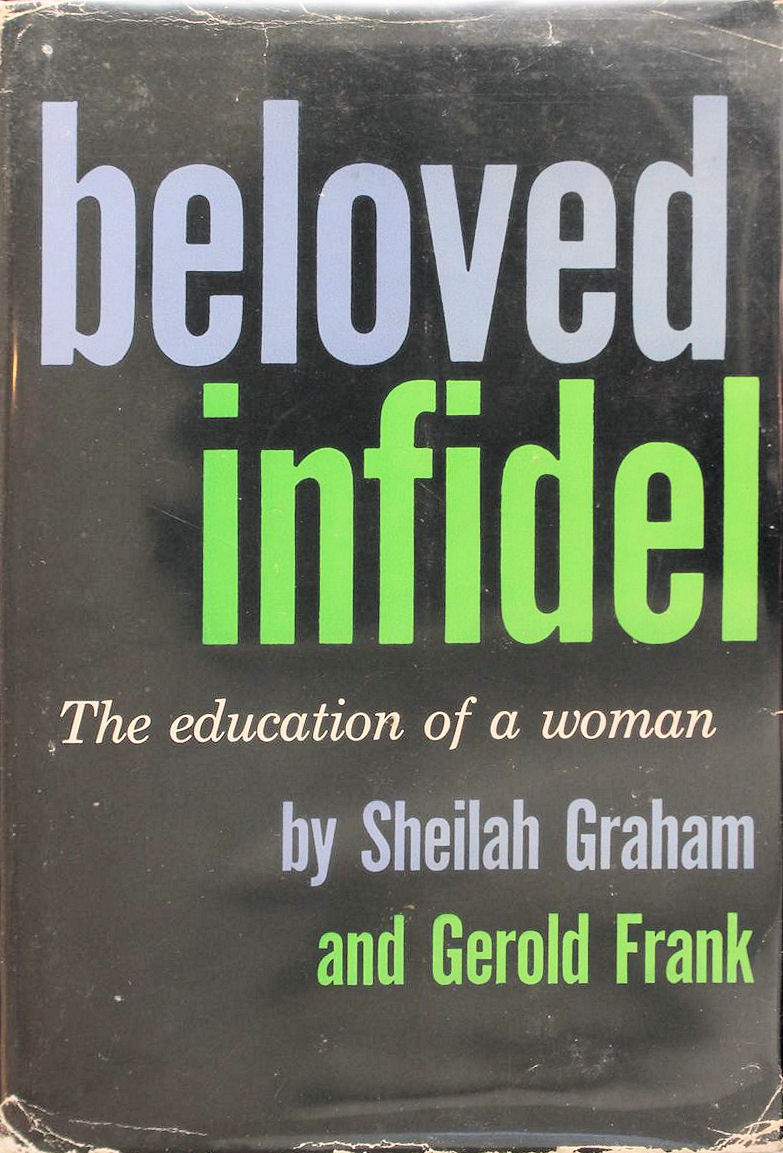

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

Book III

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

From Daily Variety, Hollywood, August 6, 1936:

Studio publicity heads may take action to ban girl correspondent for big newspaper feature syndicate. Gal has been sniping at Hollywood pictures… Has had several brushes wi:h studios… There is now talk of getting Hays to call in hatchet men.

Looking back on my first months as a syndicated movie columnist, there is no doubt in my mind that I landed in Hollywood on two left feet. The shock technique that had made SHEILAH GRAHAM SAYS so successful in New York was far less appreciated in the proud, tight little closed corporation that was Hollywood.

I had sensed at the beginning that I could reach the head of the class here in only one way—by having the sharpest, most startlingly candid column in Hollywood. Only in that way could I hope to compete with Louella Parsons, the most widely read Hollywood columnist in the country. I would write what I saw without fear or favor, as in New York I had begun by writing outspokenly of what others knew but dared not express.

The result Was catastrophic. I knew no rules, recognized no sacred cows. In my brashness there was an element of desperation, too. I knew no one in the movie colony; in the first days 1 simply invited myself to parties.

Time and again when I attached myself to a group at someone’s home and hopefully ventured a few words, the group seemed to dissolve and I would be left standing alone. Again the horror of rejection, of feeling outside, of bejng scorned —as if these people knew instinctively that 1 was of commoner clay—came over me. 1 took it, perhaps unconsciously, as an attack on my very right to exist and as always, when attacked, I wanted to leap up and claw. Thus, in a movie colony where Clark Gable and Joan Crawford were major names, 1 wrote, “Clark Gable threw back his handsome head and exposed a chin line upon which a thin ridge of fat is beginning to collect.” I wrote, “If they hadn’t said to me, ‘Miss Graham, we want you to meet Joan Crawford,’ I would never have recognized her in this tired, sallow-faced woman.” Kay Francis, 1 told my readers, painted on her famous widow’s peak. I previewed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s new film, Suzie, starring Jean Harlow: “I can’t understand why a company with the best producers, the best writers, the best actors, the best cameraman, should make a picture like Suzie which has the worst acting, the worst photography, the worst direction—”

It was this paragraph, appearing in my column before the picture’s release—just as M-G-M was enthusiastically advertising it throughout the country—that led to reports that Will Hays, Hollywood czar, might be asked to take action against me.

John Wheeler sent me an anguished telegram. “You are not Walter Winchell.” Why must I strike so hard? I could not explain. To everything I saw and heard, my reaction was immediate: this is the way 1 feel, right or wrong. Perhaps because so much of my life had been pretense 1 now had to be absolutely, compulsively honest, at whatever cost. Perhaps I merely feared exposure and thought the best way to establish a defense was to write as truthfully as 1 knew how. That, at least, would be added to the scales if and when the awful moment of exposure came.

Some of my difficulties also rose from ignorance. Marion Davies invited me to her magnificent beach house. I reported that it was a beautiful mansion, the drawing room filled with priceless paintings. “But I cannot understand why Miss Davies allows her hall to be cluttered up with such horrible caricatures.” No one informed me that these were paintings of Miss Davies in her various screen roles.

I was dined at the Trocadero Restaurant, then the most fashionable in Hollywood. I wrote: “Not even the doubtful pleasure of rubbing elbows with Louis B. Mayer can compensate for the high prices charged for rather inferior food.” No one told me that the Trocadero’s owner, Billy Wilkerson, also owned The Hollywood Reporter, a most influential trade paper. With one sentence I had made an enemy of the powerful Louis B. Mayer and had invited Mr. Wilkerson and his Reporter to declare open season on Sheilah Graham.

But Sheilah Graham’s column was read.

“Robert Benchley will show you around,” John Wheeler had told me. “I’ll write him.”

Now I sat at the Brown Derby restaurant with Robert Benchley, the celebrated wit and writer for The New Yorker magazine. He was round-faced, quizzical, with a little mustache and cornflower-blue eyes creased in a constant smile of good humor. He was given to sudden, booming laughter which made me congratulate myself on my own wit. He could not get over the fact that an English girl of my social background—tutors, French finishing school, presentation at court—should have become a Hollywood columnist embroiled in altercation with some of the biggest names in the movie colony. “Well,” he said, chuckling, “Little Sheilah, the Giant-Killer.” I should be playing croquet on some English greeni^ward instead of frantically dashing about from studio to studio picking up gossip.

We had discovered that we were neighbors. I had taken a small apartment on Sunset Boulevard; Benchley lived across the street in a hotel romantically named, “The Garden of Allah,” a favorite residence of screen writers. Once owned by AUa Nazimova, the great silent screen star, it consisted of tiny two-story Spanish stucco bungalows, quite charming, each with two apartments. They surrounded a main house with pool and patio where pretty starlets promenaded in their brief swim suits. Benchley and 1 spolce of people we knew—Deems Taylor and Dorothy Parker were his close friends—and when I finished the glass of sherry in front of me, he said, “Let me order something else for you.” Before I could stop him, 1 was served a gin drink.

I looked at it doubtfully. “Are you sure these mix? I’ve heard you can get deathly ill—”

Benchley grinned. “Take my word for it,” he said. “Best mixture you could possibly have.” I drank it down and before I reached my apartment a few minutes later, I was deathly ill.

Next day Mr. Benchley was on the phone. How did I feel? he asked solicitously. I was furious. If this was Benchley humor, he could save it for The New Yorkerl

“Yes,” he said, sadly, in a most apologetic voice. “I was afraid of that.” I heard his self-deprecating chuckle. “After you left I began to think perhaps I might have given you very bad advice.” As a peace offering, he invited me to dinner. I accepted and all was forgiven. Through Benchley, in the weeks that followed, I came to know his fellow screen writers at the Garden of Allah —Edwin Justus Mayer, author of Children of Darkness, John O’Hara, who had just written Butterfield 8, Marc Connolly, author of Green Pastures. I was delighted to be greeted again by Dorothy Parker, who had come to Hollywood with Alan Campbell, a playwright she had just married. I began to know Hollywood.

It was, I discovered, a frantic city and a slumbrous village, in which great wisdom and great absurdity, enormous talent and enormous mediocrity, existed side by side. The Hollywood I came to was the Hollywood of Norma Shearer and Shirley Temple, Jean Harlow and Constance Bennett; where friends at a dinner hid a tape recorder under the chair of John Barrymore as he whispered romantically to Elaine Barrie, and everyone wagered huge sums on Jock Whitney’s ponies at the newly opened Santa Anita track. It was the Hollywood of the President’s Birthday Ball, of Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, Mary Pickford and Buddy Rogers, Ernst Lubitsch and Irving Thalberg—a city of dreams and dream makers where the sun shone brightly and only when you thought about it did you realize that you were chilled… That first year and a half, until the summer of 1937, I was a girl on the town and enjoyed it. By now Johnny was resigned to our divorce: in early 1937 I instituted proceedings. My papers would be ready in June. After the first outcry over my column, the protests had died down and I discovered how pleasant Hollywood could be for an unattached girl who earned her own living, was beholden to no man, and whose social and professional life so neady complemented each other that it was difficult to know where duty ended and pleasure began. The items for my column came not only from my conscientious daily visits to the studios but from my friends— and that circle grew.

Through Bob Benchley and Eddie Mayer, a big, thoughtful, extremely good-hearted friend, I came to know many eligible men in Hollywood. I was always on tap for tennis or dancing, or to be taken to dinner, or to a party at the David Selznicks, or the Basil Rathbones, or the Frank Morgans. It was preferable to go escorted than to go alone. And in the midst of my busy days, running through them like a leitmotiv to dull the sense that time was fleeing, were the affectionate letters from Lord Done-gall reminding me that if and when I made up my mind in far-off Hollywood, his lordship would be on hand.

In June I made a quick trip to London for my divorce, and once again saw Johnny: the meeting was sad, but we parted friends. On my last day I lunched with Donegall.

I remember I had just finished my steak-and-kidney pie when an elderly man at another table waved to me. 1 waved back. Donegall asked curiously, “Who is that?” I wiped my mouth with my napkin. “My lawyer, Mr. T. Cannon Brooks, a most respectable gentleman.” And, I added, “It may interest you to know that 1 got my divorce this morning.”

Don nearly dropped his knife and fork. “What!” he exclaimed, delightedly. “How could you have sat through the whole meal without telling me?” For a moment he was overcome. “Sheilah, darling,” he said. “Now the way is clear!” He took my hand and pressed it fervently, his large brown eyes brimming with emotion. I was touched. I thought, I am fond of this man. I could learn to love him. I had not told him about the divorce because I feared he would hunt through the vital statistics and come upon the notice and so learn my real name. But Donegall did not press me. He was too busy with plans. “Well! Now that you’re free I’m coming to Hollywood myself to make up your mind for you. You’ll see 1 mean this. Til be there in two weeks.”

Two weeks later Donegall turned up in Hollywood to urge his suit. He took me to a fashionable jewelers and bought me an engagement ring. As he slipped it gently on my finger he said, ‘This will do until I have one made up in London for you.” He met Bob Benchley and liked him instantly. “Bob will be our best man,” said his lordship masterfully. We would be married on New Year’s Eve—under British law I could* not remarry until six months had elapsed. Our honeymoon would be spent on a cruise around the world. Now he had to return to London—there was Mother to persuade, he was sure he would succeed, but if she proved difficult, we’d go forward with the marriage anyway. He kissed me long and ardently. Was my mind made up?

Only now, as Donegall’s plans took such confident shape, did it occur to me that this could come true. Perhaps, I thought, this isn’t a top-of-the-bus dream. He means it. He followed me to Hollywood to ask me. He has given me the ring. I dared believe it, and I found myself trembling. It could happen. I saw the headlines: “Cochran Young Lady Marries Marquess.” I thought, this will be the most fantastic climax of all to this fantastic journey I have taken through life.

I saw the proud coronet on my stationery, my lingerie, my linen, the centuries-old coat of arms. I saw myself at Buckingham Palace, sitting as a marchiojiess, a lady, a viscountess and a baroness, above all other peers of the realm, below only the dukes and princes of the blood royal. I saw my name and the name of my issue in Burke’s Peerage, and in Debrett. The gentle birth I had been denied and had envied every waking moment since I first knew who 1 was, I would now bestow upon my children…

I thought, almost fearfully, am I strong enough to see this through? Can I get away with it? Must I tell everything to Donegall? Perhaps 1 don’t have to tell Donegall everything.

I accepted the hand of my suitor, the Marquess and Earl of Donegall, the Viscount of Chichester, the Earl of Belfast, the Baron Fisherwick of Fisherwick, the Hereditary Lord High Admiral of Lough Neagh.

Benchley was among the first to congratulate us. He would be honored and delighted to be the best man at our wedding. When was Donegall returning to London? Tomorrow, said my fiance, “Then we’ll celebrate tonight,” said Benchley. He was all enthusiasm. “Let’s have a party.” He thought for a moment, and added, with a grin, “It’s July Fourteenth—Bastille Day in France. We’ll celebrate the Fall of the Bastille, too!”

And at the party Robert Benchley gave to celebrate my engagement to Lord Donegall on the night of July 14, 1937, I saw F. Scott Fitzgerald for the first time.

Next chapter 16

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).