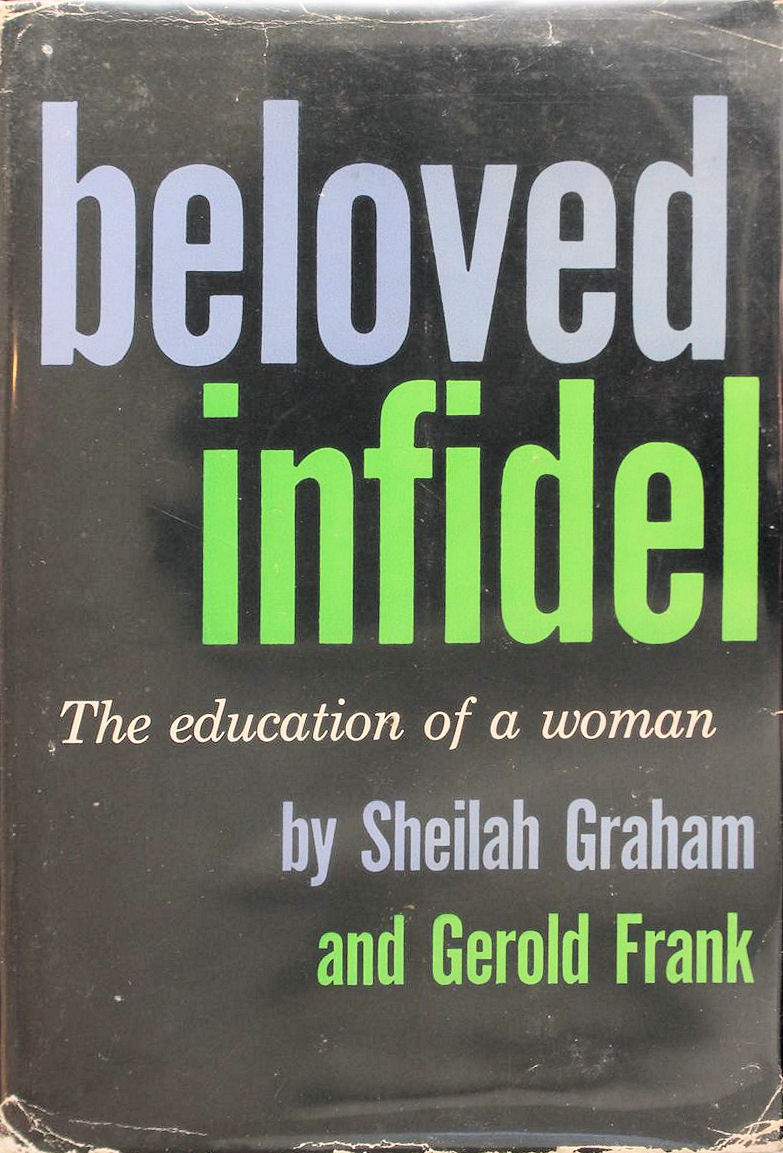

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

It began at my house high in the Hollywood hills, which I’d rented a few weeks before. Benchley lent me his German boy to serve. Donegall and I were toasted in champagne, and I wandered happily among my guests— Eddie Mayer, Frank Morgan, Lew Ayres, Charlie Butter-worth, writers and actors and their wives and girls. From my little terrace the lights of Hollywood far below gleamed and flickered like tiny paper lanterns strung through the streets of some distant, festive city floating in the sky. It was a night for dreams.

I clung to Donegall’s arm. What more lovely dream of splendor could I wish for? The toasts and good healths came fast. Benchley’s boy served industriously, we all drank, and amid the laughter and gaiety I heard Bob shout, “Let’s all go to my place! Remember the Bastille!”

Noisily we piled into half a dozen cars parked outside and drove down the hill to the Garden of Allah. We trooped into Bob’s small drawing room and there was more champagne, and more guests—Dorothy Parker, Alan Campbell, a European actress named Tala Birrell—• and the party went on even more merrily. Donegall’s arm was around me, Frank Morgan was telling a hilarious story, and almost casually I became aware of blue smoke curling lazily upward in the bright radiance of a lamp. Then I saw a man I had not seen before. He sat quietly in an easy chair under the lamp, and from a cigarette motionless in his hand the blue smoke wafted slowly upward. I stared at him, not sure whether I saw him or not: he seemed unreal, sittmg there so quietly, so silently, in this noisy room, watching everything yet talking to no one, no one talking to him—a slight, pale man who appeared to be all shades of the palest, most delicate blue: his hair was pale, his face was pale, like a Marie Laurencin pastel, his suit was blue, his eyes, his lips were blue, behind the veil of blue smoke he seemed an apparition that might vanish at any moment. I turned to laugh with Frank Morgan; Bob spoke to me; when I looked again, the chair was empty. Only the blue smoke remained in the heavy air, curling upon itself as it slowly flowed into the updraft of the lamp. I thought, someone was there.

I turned to Bob. “Who was that man sitting under the lamp? He was so quiet.”

Bob looked. “That was F. Scott Fitzgerald—the writer. I asked him to drop in.” He peered owlishly about the room. “I guess he’s left—he hates parties.”

“Oh,” I said. “I v^sh I’d known before. I would have liked to talk to him.” I thought, he’s the writer of the gay twenties, of flaming youth, of bobbed hair and short skirts and crazy drinking—the jazz age. I had even made use of his name: in SHEILAH GRAHAM SAYS, when I wanted to chide women for silly behavior, I described them as passe, as old-fashioned F. Scott Fitzgerald types, though I had never read anything he wrote. It might have been interesting to talk to him.

Then Benchley was launched on a long, brilliant speech in which every sentence, Eddie Mayer told me later, was the tagline of a dirty story, and I quite forgot the man under the lamp.

Next morning I drove Donegall to the airport and saw him off to New York, London—and his mother. “She’ll weaken, I know she will,” he assured me. He was most tender, most affectionate, on the ride out. “Good-by, your ladyship,” he said, and kissed me. I drove back lost in lovely dreams. Your ladyship!

A few days later Marc Connolly asked me to a Writers’ Guild dinner dance at the Coconut Grove in downtown Los Angeles. He had taken a table for ten; so had Dor-orthy Parker, chairman of the evening. I don’t know how it happened but a moment came when I found myself sitting all alone at our long table, and at Dorothy’s table, parallel to ours, sat a man I recognized as Scott Fitzgerald, all alone at his table. We were facing each other. He looked at me almost inquiringly as if to say, I have seen you somewhere, haven’t I? and smiled. I smiled back. Seeing him clearly now, I saw that he looked tired, his face was pale, pale as it had been behind the veil of blue smoke that night at Benchley’s, but I found him most appealing: his hair pale blond, a wide, attractive forehead, gray-blue eyes set far apart, set beautifully in his head, a straight, sharply chiseled nose and an expressive mouth that seemed to sag a little at the corners, giving the face a gently melancholy expression. He appeared to be in his forties but it was difficult to know; he looked half-young, half-old: the thought flashed through my mind, he should get out into the sun, he needs light and air and warmth. Then he leaned forward and said, smiling across the two tables, “I like you.”

I was pleased. Smiling, I said to him, “I like you, too.”

There was silence for a moment. This was my first evening out since my engagement and, in a magnificent evening gown of gray with a crimson velvet sash, I felt exquisitely beautiful, as befitted a girl who was to become a marchioness. I felt myself radiant, caught in the golden haze as when I parted the curtains and stood before the audience in Mimi Crawford’s place on the stage of the London Pavilion. ... To be sitting now, alone, while everyone was dancing, seemed such a waste. I said to Mr. Fitzgerald, “Why don’t we dance?”

He smiled again, a quick smile that suddenly transfigured his face: it was eager and youthful now, with all trace of melancholy gone. “I’m afraid I promised to dance the next one with Dorothy Parker. But after that—”

But when everyone returned to their tables the band stopped playing; there were many speeches and when they were over everyone scrambled to go home and I did not see him again. Marc Connolly took me home and once more I had brushed against this quiet, attractive man and we had careened off in opposite directions.

Yet something was at work.

At seven o’clock the following Saturday evening Eddie Mayer telephoned just as I was closing the door to go out. “What are you doing tonight?” I was bound for a concert at the Hollywood Bowl wtih Jonah Ruddy, resident correspondent for several British newspapers, who had helped me on a number of stories. I told Eddie.

“A pity,” he said. “Scott Fitzgerald is with me and I wanted you to join us for dinner.”

I said, unhappily, “I’d love to, Eddie, but it’s really too late to cancel Mr. Ruddy—”

“Why don’t you bring him along?” suggested Eddie.

We met at the Garden of Allah and went to the Clover Club, a gambling place with dining and dancing upstairs. Scott said little on the way out—there was a reticence about him that made me feel he belonged to an earlier, quieter world. His clothes, too, spoke of another time: he wore a pepper-and-salt suit and a bow tie, and though this was July, a wrinkled charcoal raincoat with a scarf about his neck and a battered hat. It was hard to believe that this was the glamor boy of the twenties. At the bar we were introduced to Humphrey Bogart and his wife, Mayo Methot. “Won’t you have a drink with us?” Bogart asked Scott.

He shook his head and said, pleasantly, no. Bogart seemed surprised. We sat with them for a few minutes and Scott made some light jokes about a picture he was writing for M-G-M. The Bogarts laughed and I caught respect and deference. Jonah Ruddy, who seemed to know something about everyone in Hollywood and so was not easily awed, seemed most impressed, too.

Now, finally, I danced with Scott, and as we danced, the room and everyone in it—Eddie, Jonah, the others dancing and chattering about us—faded away. It is hard to put into words how Scott Fitzgerald worked this magic, but he made me feel that to dance with me was the most extraordinary privilege for him. He did it by his words, which seemed directed to me alone; he did it by the way he tilted his head back, a little to one side, as though he were mentally measuring, and then took complete possession of my eyes, my hair, my lips, ail with a kind of ddighted amazement at his good fortune to be dancing with me. He gave me the delightful feeling that hundreds of attractive men were just waiting for the chance to cut in on him and to snatch me away because I was so irresistible—and the feeling, too, that he would not let me out of his arms if he had to fight every one of them. He did it, too, by the rapt attention he gave to what I said, as though I was never to be dismissed as shallow or unimportant, that my opinions were of value and were to be respected. Once, to something I said, he exclaimed, “Oh, that’s very witty. I want to remember to write it down when we get back to the table.” I was immensely flattered. This man appreciates my mind as well as my face.

We danced; we never sat down. The room went round and round. Now, though the courtliness, the exquisite manners were-there, on the floor he was like an American college boy. He was only a few inches taller than I but he was sinewy, strong, and firm, his step gay and youthful and sometimes we danced cheek to cheek. I thought, now I know what it must have been like to dance at a college prom. I said, “I love dancing!” He said, “I do, too.” I went on, “When I was a girl in England, I lived to dance—it gave me such a feeling of freedom—” He nodded, his blue eyes still wonderingly on my face as if there were nowhere else to look. He was so easy to talk to, so understanding. In London I had met Evelyn Waugh, the writer, who wrote about the twenties too, but Waugh had been so bored with me that I had been struck dumb. I could talk to this man. He asked me endless questions. How old was I? “Twenty-seven,” I said, lying by a year. How old was he? Forty, he said, with a httle grimace. “How did a girl as beautiful as you come to be a columnist?” he asked. I preened myself and smiled. I had been on the stage, I had been a dancer, I tried to become a Shakespearean actress, but that had been dreadful. I told him of the note from Kenneth Barnes, Director of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art: “It is imperative that you improve.” He put his head back and laughed. He thought it very funny.

We danced the tango; we took over a corner of the floor as our own and danced separately, experimenting with the most amazing steps; we laughed together, struck at the same moment by the same absurdity; we were completely impervious to our surroundings. I thought, this man is not forty, he is a young man, he is a college boy, he is utterly delightful. When, finally, we returned to our table where Eddie and Jonah sat with admirable patience, we looked at them as though they were strangers who had usurped our seats. Scott took out a notebook and to my intense pleasure wrote down my bon mot. Then he sipped a Coca-Cola and took me on the floor again while Eddie and Jonah grinned at each other. Would I have dinner with him? I said, yes. When? I said, Tuesday. Good, he said. Finally our little party broke up and I was taken home. And I thought about Scott.

He had spoken hardly at all about himself, deliberately, it seemed, focusing the attention on me. “Eddie told me that you’re engaged to the Marquess of Donegall,” he said. I nodded. “And youVe to be married in December?” I said yes, but I could not help smiling up at him. If I flirted, it was because it was my nature to flirt; but far more than that, it was because I liked him enormously, I liked the way he made me feel about myself. I wanted to please him because he admired me and from what little I had seen and heard, to be admired by Scott was a great compliment.

Eddie told me later that Scott had arrived in Hollywood only a few days before my party and had moved into the apartment directly above him in one of the Garden of Allah’s charming little bungalows. He had come west on a six-month contract to write the screen play for A Yank at Oxford. Eddie smiled a little sadly as he told me this. They had hired Scott Fitzgerald, he went on, because Scott’s first novel, This Side of Paradise, a remarkable first novel which made him famous as a young man just out of Princeton, dealt with college youth. But from This Side of Paradise to A Yank at Oxford — Eddie shook his head. It was obvious that he thought it a great waste of this man’s time to write for pictures.

On Saturday night Scott had wandered downstairs and dropped in on Eddie. Because he seemed lonely, a little lost, Eddie suggested they dine together. Scott said, “You know, I saw a girl here I like.” He described her. “You must mean Sheilah Graham,” Eddie said, and when Scott remarked, almost casually, “I’d like to meet her,” Eddie telephoned me.

By Tuesday I had learned a little more about Scott Fitzgerald. He was married but his wife Zelda, a great beauty with whom he was very much in love, was in a mental institution and had been for some time. It was a tragic story. So that, I thought, lies behind the sad line of his mouth, explains the hint of melancholy lurking behind his reserve. From scraps of conversation between Eddie and Bob Benchley, I gathered that Scott and Zelda had lived a rather daring, unconventional life, full of outrageous pranks and escapades. Once they had jumped fully dressed into the fountain in front of the Plaza Hotel in New York. They would hire taxicabs and ride on the hood. I thought to myself, that isn’t screamingly funny. I gathered, too, that though Eddie and his friends looked on Scott as a great American writer, nobody paid much attention to him now. People were reading his contemporaries—Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, John Steinbeck—^while Scott was appearing only now and then in magazines such as Esquire.

Tuesday afternoon a telegram arrived from Scott. He could not keep our engagement that evening. His daughter had just arrived from the East and he was taking her to dinner. I recalled that he had spoken of his iBfteen-year-old daughter, Scottie, who attended boarding school in Connecticut. Helen Hayes, a friend of the Fitzgeralds, was bringing her to California on a brief visit. I stared at the telegram, astonished at the intensity of my disappointment. For a moment I was dismayed: how could I be so shaken by this? I was to marry Donegall in six months: how could I be so affected by a broken date with a man —and a married man—whom I had seen for the first time less than ten days ago? Yet suddenly I knew I must see Scott again. Nothing else mattered. I telephoned him. “Scott,” I said, “it makes no difference, your daughter being here. I’d like to meet her. Can’t we all go to dinner?”

There was a pause. Then, reluctantly, “All right. Fll pick you up at seven.”

Scottie was a pretty, vivacious girl with her father’s eyes and forehead, which made me like her instantly. Two boys she had known in the East had called and Scott had invited them, too. At dinner, however, Scott was an altogether different man from the charming cavalier who had danced with me. He was tense and on edge: he was continually correcting his daughter unfairly and embarrassingly. “Scottie, finish your meat,” and “Scottie, don’t touch your hair,” and “Scottie, sit up straight.” She endured it patiently but now and then she turned on him with a despairing, “Oh, Daddy, please—” As the evening progressed Scott grew increasingly nervous, drumming on the table, lighting one cigarette after another, and drinking endless Coca-Colas. It was obvious that he loved his daughter but he fussed about her unbearably. My heart went out to Scottie who would sit there, silently, and sigh as if to say, why doesn’t he stop it? Then she and the boys would fall to giggling, only to have Scott interrupt with a heavily jovial story which they apparently found not funny at all. Scott and I danced a few times but he was distracted and worried. The evening was a strain for everyone. I thought, is this the man I found so fascinating? This anxious, middle-aged father? It was a relief when he said to his daugher, “Scottie, don’t you think it’s time for you to be in bed? I ought to take you back to the hotel.” We dropped the boys off, then dropped Scottie at the hotel where she was staying with Miss Hayes, and Scott took me to my home on the hill.

He stood at the door, saying good-by. I felt utterly lonely and on the point of tears. There had been such a magical quality about him the other night and now he was only a faded little man who was a father. He said good night. I did not want him to go; I felt inexpressibly sad that something that had been so enormously exciting and warming had gone. I thought, oh, what a pity to lose this. In the half light, as he stood there, his face was beautiful. You could not see the tiredness, the grayness, you saw only his eyes, set so beautifully in his head, and the marvelous line from cheekbone to chin. I wanted desperately to recapture the enchantment that had been and I heard myself whisper, “Please don’t go, come in,” and I drew him in and he came in and as he came in he

kissed me and suddenly he was not a father anymore and it was as though this was as it should be, must be, inevitable and foreordained.

Next chapter 17

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).