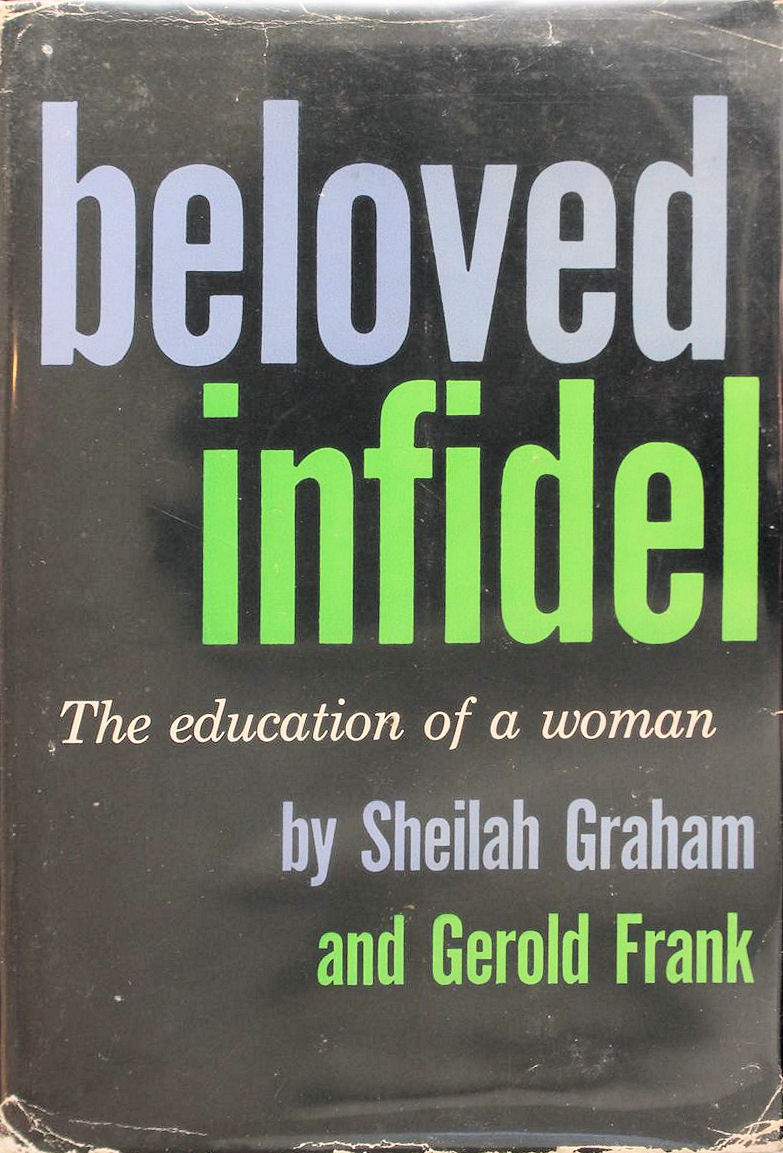

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Armed with one hundred dollars, a return ticket, just in case, and a bagful of letters of introduction, I arrived in the United States in June, 1933. The most important American syndicate, I had been told, was the North American Newspaper Alliance, headed by John Wheeler in New York. When I walked into his office I could not know that I was meeting the man who was to be my employer through the years. I saw a pink-faced tough-looking man who swiveled around in his chair to look hard at me as I entered, an eager smile on my face. He had a half-smoked cigar in his mouth, he wore a green eye-shade and he spoke gruffly. His office, off Times Square, was spare, and simply furnished, with a few World War photographs in which I recognized him, much younger and even tougher-looking. Cigar, eyeshade, gruffness and all, he looked exactly as the American movies had led me to picture an important New York newspaper executive.

He read my letter of introduction, chewing his cigar from side to side. “Let’s see what you’ve done,” he said, abruptly. I opened a large envelope and drew out a clipping of my article on stage-door Johnnies. He read it swiftly. “Not what we want,” he barked, handing it back. Like a mother dispensing sweets to a child—one at a time, not to spoil him—I produced a second clipping. This was dismissed, too. When he handed back the third, I felt sick at heart. I gave him the entire envelope. He went through the rest of the material, stopping at my piece about young wives and middle-aged husbands. He read it through. “Pretty good,” he said.

Since I could never stand suspense, I blurted, “Then will you give me a contract?”

He looked at me. “I don’t know about that,” he said, dryly. “Suppose you leave a set of clippings here and get in touch with me in a few days.”

I dared to say, “I hope you’ll give me the contract right away, Mr. Wheeler. You know, you’re not the only syndicate I’m seeing.”

He smiled for the first time. “You get in touch with me in a few days,” he repeated. He rose and showed me to the door.

Mr. Wheeler liked my articles. I was obviously too much the beginner to write a syndicated column, but he referred me to Albert J. Kobler, publisher of the New York Mirror. On the strength of my English clippings, I was hired at forty dollars a week. Mr. Wheeler, whose advice I asked, suggested I might earn additional money by selling his NANA features to the newspapers, and so in my spare time 1 trotted about to the various editors.

At the Evening Journal, Mary Dougherty, Woman’s Editor, bought nothing but gave me an idea. “You ought to write your impressions of New York. Why don’t you try it for us?”

I had already gained definite impressions of New York. I determined to write a shocking, attention-getting story for Miss Dougherty. Entitled, “Who Cheats the Most in Marriage?” I examined the habits of the French, English, Germans, and Americans, and concluded that the English were the most guilty. I spoke of the menage a trois as a common occurrence in England. “It is not unusual for all three—husband, wife, and lover—to live under one roof, the lover paying the bills while the husband looks the other way,” I wrote. Among the French, I went on provocatively, the favorite phrase was, “Que-voulez-vous?”—”What do you expect?”—if a man spent his afternoons with his mistress, his nights with his wife. The Germans, I declared were too stodgy to care. As for the Americans, I confessed that my first impression of New York had been two-fold: first, men without wives, because the wives had all left the hot city for the country; and second, apartments without carpets, for the carpets like the wives had been sent away for the summer. These impressions belonged together, I declared, because invariably the men without wives entertained young ladies in the apartments without carpets. If it were not for the fact that gathering alimony is the main occupation of American women, I concluded, Americans would cheat the most.

I mailed it to the Evening Journal and went off to my job on the Mirror, where I was reporting events of no consequence.

Next morning the excitement broke. The Evening Journal wanted me in their offices, immediately. My article was terrific! The moment I arrived—on my lunch hour from the Mirror —a photographer was called and I was photographed in half a dozen poses—on the telephone, at the typewriter, smiling at the reader. They were going to publicize me as their find of the year— Sheilah Graham, the audacious, saucy lady journalist from England. How much did I want to work for them?

I said, “A hundred a week.” I always liked big round numbers.

Even an audacious, saucy lady journalist from England wasn’t worth one hundred dollars a week in 1933. Miss Dougherty countered, “We can pay you seventy-five dollars.”

Seventy-five dollars from the Evening Journal added to forty dollars from the Mirror made one hundred fifteen dollars a week—”That will be acceptable,” 1 said with dignity.

“Fine,” said Miss Dougherty. I was hired.

The denouement came the following day when my story appeared in the Journal. The Mirror protested vehemently. How could I work for the Journal when I was on their payroll? And at the Journal, an icy Miss Dougherty called me in. It took some time to convince her that I was so new to journalism that I thought it proper to work for two newspapers at the same time in the same city. I was forced to give up the Mirror. But overnight I had become a full-fledged newspaper writer, my articles appearing three times a week under a headline that blazed: SHEILAH GRAHAM SAYS.

In the two years I spent in New York I became what I had pretended to be—a professional journalist. As on the stage, I was an amateur who learned how to keep up with professionals. I did so by combination of daring, brazenness, and desperation. I was the kind of reporter who climbed through the bedroom window to steal the photograph demanded by the city editor. I was terrified of small planes—yet I went up in a tiny, open, two-seater to cover Lindbergh’s arrival from his top-of-the-world flight. I dreaded having anything to do with violence, yet I attended the Hauptmann murder trial, interviewed women moments after they learned their husbands had been slain in a gang war, and even surreptitiously entered Al Capone’s home in Florida to describe its lavish interior for Evening Journal readers.

I stopped at nothing and everything had its value for me. When I was sent to interview Dorothy Parker, the distinguished writer for The New Yorker magazine, I asked her if it was true she had just been tattooed—and where? She laughed apologetically. “Yes, it is true—but only on my arm, I’m afraid,” and invited me in for cocktails. I was dispatched to demand of George Jean Nathan, the drama critic, then seen everywhere with LilHan Gish: “When are you going to marry Miss Gish?” It was a brazen thing to ask. He smiled. “I can’t tell you when I’m going to marry, but I’ll tell you why I’m not going to marry her,”—and I obtained an even better story.

Through it all, John Wheeler was my friend and counselor. When I ran out of provocative ideas for SHEILAH GRAHAM SAYS, he suggested, “Write a piece saying that all dogs should be kicked out of New York. Tell them it’s ridiculous to keep dogs in city apartments— unfair to dog and master.” I did, and the Evening Journal was delighted to find itself deluged with angry letters demanding that Sheilah Graham go back where she came from. It was Wheeler who introduced me to the world of American publishing and advertising—Herbert Bayard Swope, the editor; Bruce Barton, head of his well-known advertising firm; Deak Aylesworth, president of NBC; Kent Cooper, general manager of the Associated Press. Through the people I met, and with my letters of introduction, I soon found myself part of New York sophisticated life.

Now instead of Quag’s, it was the Stork Qub, with Quentin Reynolds and Deems Taylor holding forth; instead of castles in Northumberland it was country homes in Connecticut where I sat on the floor listening to George Gershwin at the piano, and the voices I heard were those of Gene Tunney and Heywood Broun. Now I played tennis at the Piping Rock Club on Long Island and went riding on Vincent Astor’s magnificent estate in Rhinebeck.

And all the time as the months passed, I sought to learn. Americans, I discovered, differed from the English. They were not ashamed of knowledge; indeed, they were eager for it; they did not think it bad taste to reveal what they knew, to check and challenge and throw themselves into exciting discourse. In polite English society one never showed off how much he knew. That was for Bloomsbury intellectuals and the odd types who climbed on soap boxes in Hyde Park. Now, at the parties I attended, I discovered a new facet of America—for the first time, I met women intellectuals of grace and charm.

In England, the lady intellectuals I had brushed against were gaunt, dyspeptic women, forbidding and spartan, who gave erudition an unpleasant quality. They were women who never seemed to enjoy food: I hoped never to be so educated that I’d not care what I was eating.

Enviously I watched Dorothy Parker. Everything this warm, attractive woman said, seemed to get into print. Men flocked to her. I thought—you see, a woman need not be strikingly beautiful to draw admirers about her: she can do it, too, if she has high intelligence and flashing wit and knows a great deal about everything going on in the world. And it came to me that I would have a more difficult time getting by in America simply on a smile and a pretty face.

At one dinner party I met Clare Boothe, the playwright who as Clare Boothe Luce later became Ambassador to Italy. Here was cool beauty, brains, and talent. It proved an agonizing evening for me. About twenty guests, a cross-section of New York’s literary and theatrical society, were present and the party crackled with epigrams and witty conversation. Someone suggested a game of hypothetical questions: suppose President Roosevelt, Pope Pius, and George Bernard Shaw died: which death would represent the greatest loss to the world? If Shakespeare and Plato met today, how might their conversation go? Everyone made a contribution but me. The evening was almost over and I had said nothing. I became desperate. Somehow I had to join in the conversation. I was wringing wet with the agony of feeling completely outside this scintillating group. Miss Boothe, who had been speaking brilliantly, paused for a moment to open a ruby-studded compact and powder her nose. I spoke up. In the dead silence I said, “That’s a very pretty compact.” No one said anything. Miss Boothe looked at me, finished powdering her nose, clicked her compact shut, put it back in her bag, and went on talking. That was the only thing I said all evening.

I went home and cried.

My ego was soothed when I received an affectionate letter from Lord Donegall. He thought constantly about me, he wrote. He was sorry he could not have seen me before I left. He was sending me under separate cover an important record which he wanted me to play as soon as possible.

When the record arrived a few days later, I placed it on my phonograph, settled comfortably with a bun and a glass of milk, and listened. His voice came: “My darling Sheilah. I have thought of so many ways to phrase this, and the simplest is the best. I want to marry you when you are free. I am hopeful that I can bring Mother on our side. Do think about this and consider it. And please don’t send me an answer you don’t mean.”

I played the record several times and wrote to tell him how flattering his proposal was, and that I would think about it. I had no wish to marry Donegall and return to live in England, yet I could not bring myself to close the door completely. It reassured me to know that the Marquess of Donegall waited to marry me. It was pleasing to toy with the dream of myself as a marchioness.

My ego was further salved when John Wheeler invited me to have a drink at the Hotel Marguery and meet Lee Orwell—then publisher of the Evening Journal —and several of his friends. We were served and sat waiting when Mr. Orwell entered, accompanied by a fair, pretty woman of forty, who was introduced to me as Miss Margaret Brainard. Years later she told me she had thought I was an alcoholic when she met me that afternoon, for I had six old fashioneds lined up in front of me.

“Are you going to drink all of those, my dear?” she asked.

I shook my head. “I’m not drinking anything—I just eat the cherries.”

Mr. Orwell broke into laughter and John Wheeler said dryly, “Don’t you think it might be less expensive if I bought you the cherries without the drinks?”

That had never occurred to me.

Margaret thought this very amusing. She took a liking to me and became my closest woman friend in New York. I confided in her my hopes of becoming a successful, syndicated columnist, my distress at not knowing American customs. I told her about the marquess who waited for me—about everything save my true past.

I threw myself into work. I earned more money— sometimes as much as four hundred dollars a week—with radio interviews, magazine articles, and special assignments. In 1934, King Features sent me on a quick trip to London to cover the marriage of the Duke of Kent to Princess Marina of Greece. Johnny—as ever Johnny— met me at the dock waving a copy of the Daily Express with one of my New York stories. “You’re a success,” he shouted. “You’re famous!”

On the visit Johnny and I finally agreed to a divorce. He was most reluctant, but he knew that the farce of our marriage could not continue indefinitely. “All right,” he said sadly, at last. “But not right away, Sheilah. If you still want it after you’ve been in America for another year, I won’t contest it.”

I do not know how seriously I had Lord Donegall in the back of my mind when I talked about divorce to Johnny. When I saw Don, briefly, I said only that I was still thinking about his proposal. He must be patient. And Donegall, busy dashing about the country, seemed prepared to be patient.

Upon my return to the United States, an exciting new job appeared. Elsie Robinson, who wrote an advice-to-the-lovelorn column in more than one hundred newspapers, was about to retire. Eagerly I applied for her position. To my intense disappointment, I did not get it. Only later I learned why. When my name reached Joseph P. Connolly, head of King Features, which owned the column, he said, “Oh, no. That young lady is much too sophisticated.” And he gave the column to some one else.

My fault had been that I had pretended too well. Mr. Connolly had seen me at publishers’ dinners, laughing uproariously each time an off-color story was told. Actually, I hadn’t understood them: but I wanted these brusque, successful, expansive Americans to think that I understood. I wanted to belong.

I brooded over it for weeks.

Then, quite unexpectedly, my New York interlude ended. The North American Newspaper Alliance’s Hollywood columnist, Molly Merrick, was due to renew her contract but wanted more money. Mr. Wheeler was not prepared to acquiesce, and it appeared that NANA would find itself without a Hollywood column. “I’ll take the job at whatever she’s making,” I told Wheeler eagerly. “I know I can do it.” I pleaded for the chance. Hollywood to me was sham and glitter and I thought myself qualified to understand sham and glitter.

Mr. Wheeler considered my request and finally yielded. Miss Merrick had been earning two hundred dollars a week: he slashed me to one hundred and twenty-five dollars a week, but he gave me the job. He was willing to let me prove myself. He knew that any girl who ordered old fashioneds for the cherries alone was not too sophisticated to write a gossip column from Hollywood.

On Christmas Eve, 1935, I flew to the West Coast. As the plane took off I suddenly felt blue and depressed. Was this a mistake? Should I have remained in New York where I earned three times as much? But it was not money I had come to the States for—or was it? What did I want?

I thought a great deal about this as I sat on the plane, listening to the steady roar of the motors. What was it I looked for? Love, security, a home—a family? I desperately wanted a child. I remembered a day at the orphanage when Miss Walton asked us, “What would you like to be when you grow up?” The other girls had said, nurses, cooks, teachers, nuns, typists, artists, dancers. I had replied, “a mother.” It was true. Since I had no family, I yearned to create a family, out of myself. Oh, to have something that belonged to me, that was part of me—to be related to at least one living person in the world! That was part of it—to belong somewhere. That was why I loved to be with men: because they were warm and protective to me, because they made me feel beautiful and wanted and belonging.

But I had yet to find what I sought. The stage hadn’t answered my need; nor the world of society. Whatever it was, I hadn’t found it in London, and now in New York I hadn’t found it either. True, I was learning about America, and having a good time in the process—good food, good clothes, gay companions—but I lived in a vacuum. I was still spinning about, looking—what was I looking for? Was it a man? Someone to care for me, someone who would love me body and soul and want me with him until the day he died? Someone whose love would rescue me from the fraudulence of my life? Was that it? Or was it success such as I had still not known, wealth that would allow me every luxury, the gratifying knowledge that I was climbing, climbing, gaining a higher rung each time… Was it to be a marchioness? Even that seemed empty, now that it was within sight…

My reverie was interrupted by the stewardess. She came down the aisle distributing pink paper hats and paper cups of champagne. “Just a little of the Christmas spirit,” she said gaily.

I sipped the champagne and sat with my paper hat perched crazily on my head and looked out the window into the dark night.

Next chapter 15

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).