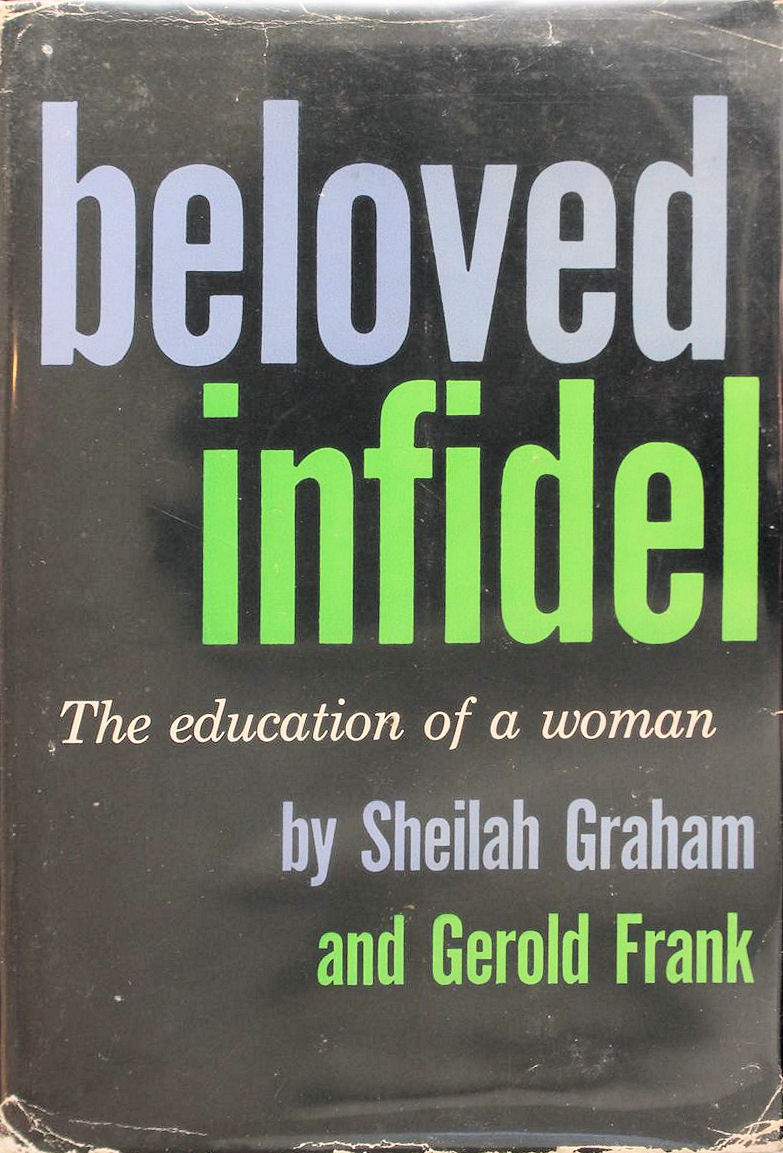

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER TEN

In her dressing room at the London Pavilion I sat at the feet of the great Mimi Crawford, star of One Dam Thing After Another. “How do you become a star?” I asked her, anxiously.

She was so sure of herself, this dainty, pale blond beauty with enormous blue eyes in a little heart-shaped face. She said, “Think of nothing else when you’re on stage except your part. Just concentrate on that and you’ll be a success.”

I took her advice. I was third from the right in the chorus and I needed only to keep in step, smile, and pirouette at the right time, but every moment off stage I stood glued in the wings and studied Mimi Crawford. I followed her every movement, the turn of her head, the coquettish glance of her eyes, the twinkling toe, the seductive turn. I had convinced myself that I would be her • understudy. I cannot explain why: no one had given me i the idea. But it seemed to me then that my ambition would burst without something to cling to. Stardom was something to cling to. And I continued my furious lessons in dancing, ballet, voice.

My concentration on her part got on Miss Crawford’s nerves. Finally she informed William Ring, the stage manager, “If you don’t get that girl out of the wings, I won’t go on.” Mr. Ring allowed me to watch from another vantage point. I memorized her entire part, learned her songs, including one I loved to sing at home to Johnny:

Mary Make-Believe,

Dreams the whole day through,

Mary Make-Believe,

Cried a little up her sleeve,

Nobody claimed her,

They only named her,

Mary Make-Believe.

Johnny, as always, encouraged me. If there was no limit to my ambition for myself, there was even less to Johnny’s ambition for me. He came to each show, to stand in the rear of the stalls, applauding wildly, and to call for me after the show at the stag^ door. Our marriage remained a secret. To the girls, Johnny had been introduced as my uncle, an affectionate elder relative who was my constant escort and chaperone.

Concealing the truth, however, led to unexpected complications. Presumed single, I was fair game for the young men about town, by whom Mr. Cochran’s Young Ladies were highly esteemed. We all received dinner invitations from London’s gay blades and young peers. For the girls this was their shining opportunity: more than one had gone from a Cochran chorus to become mistress of a great estate and possessor of a proud name. But invariably I refused all invitations. Even when Elsa, a lovely brunette who took a liking to me, asked me on double dates, I had to say, no.

One evening Elsa, with a triumphant smile, passed a calling card to me. It read Sir John Carewe-Pole, Bart. On the other side was written in a j&ne hand:

It is said that you do not accept invitations and will make no exception. I have wagered with my regiment to the contrary! 1 shall be deeply honoured if you will have supper with me next Saturday.

J.C.-P.

Elsa watched me as I read it. I shook my head. “Now Sheilah, really,” she exclaimed. “You can’t turn him down. He’s the handsomest man in the Guards! You can’t spend the rest of your life with your uncle!”

Johnny and I discussed the matter seriously. Sooner or later I must accept an invitation—or else disclose our marriage. What should I do?

“I think you’d better say yes to Carewe-Pole,” Johnny said finally. He spoke not as a husband but as a patron to a protege. “It might be an excellent expeiience for you to be the guest of someone like Sir John Carewe-Pole. He’ll undoubtedly take you to Giro’s and you’ll have a topping time and dance to your heart’s content. I’m sure he’s an honorable fellow. You’re young—why shouldn’t you enjoy yourself?”

When Saturday came, waiting for me at the stage door was a tall, dark-haired man with a small clipped mustache. He was extremely handsome in white tie and tails. He bowed and announced, “Miss Graham, I’m John Carewe-Pole. Very sporting of you to accept my invitation.” He conducted me to a taxi and helped me in.

We rode in silence. I was very ill at ease. I had never been with a Sir before. Did one speak or wait until spoken to?

My escort turned to me with a charming smile. “I enjoyed your show—very much.”

I wanted to say something more gracious than, “Thank you,” but I could think of nothing. “Thank you,” I said.

“Your dance in the first number—” he went on smoothly. “You stood right out, Miss Graham. Quite.”

I was silent. “It’s nice of you to say so,” I said. Johnny had once used that phrase.

He said, “You know, you’re very pretty—but other men must have told you this.” I nodded, uncomfortably.

“How long have you been on the stage?” “About three months,” I murmured. Now apprehension was added to my discomfort. I did not like being questioned.

“Three months? Well.” He smoothed his mustache. I felt his eyes on me. .”Must be a fascinating life, what?”

I said, carefully, choosing words with vowels I was sure of, “Yes, it is. But it’s not as easy as it looks. I must rehearse every day and take dancing and singing lessons—”

He listened courteously. “Never thought of it that way, you know.” He was silent again. Then unexpectedly^ “Did you do anything before the stage?”

I racked my brain, almost in panic. If only he would kiss me so I wouldn’t have to answer any more questions! I managed to make some kind of reply.

When we arrived at our destination—it was Giro’s—I ordered gfapefruit, which I had always associated with elegance, then sole and coffee and a chocolate eclaire. Sir John ordered champagne with dinner. I ate with painstaking care. Then we danced, mainly in silence. He saw people^he knew and bowed to them. I saw no one I knew. Then he sat down again. The silence was agony.

The evening ended, we bid good-by to each other. I had had my dinner and dance at Giro’s. He had won his wager. I never saw Sir John Garewe-Pole, handsomest man in the Guards, again.

Mimi Grawford continued in excellent health and I bided my time. Just before the end of November all of Gochran’s Young Ladies were assigned to the lobby of His Majesty’s Theatre to sell programs for a charity show. I took my place with the others. A man stroUed by and I accosted him: “Buy a program, sir?”

He was a thin, rangy man with a long nose, long face, long chin. “I’d be happy to,” he said. He shot a quick glance at me. “Don’t I know you? I’m sure I’ve seen vou before—” ^

I was sure that I had never seen him before. A little distantly, I said, “I’m Sheilah Graham. I’m one of Mr. Gochran’s Young Ladies.”

He said, still gazing at me thoughtfully, “I’m A. P. Herbert.” My haughtiness changed to awe. I had read about this man. He was the well-known writer for Punch, and author of comic operas on the London stage.

“I have it!” His face brightened. “I’ve seen you with a man in the reading room of the British Museum. Now, what on earth would one of Cochran’s Young Ladies be studying in the British Museum?”

I blushed. Mr. Herbert had seen Johnny and me. Johnny had gone to research for a newspaper article he hoped to sell. I had spent the time reading an unexpur-gated edition of The Arabian Nights, which I found naughty and fascinating.

“I read a great deal,” I replied, evading his question. “I’m preparing myself to be a star.”

“Really?” He looked at me with interest. How was I preparing myself? I began to tell him something of my lessons, my desire to better myself, my dream of starring in musical comedy. “Why don’t you let me hear you sing,” he suggested. “Perhaps I can help you.” He added that he would drop in to see our show at the Pavilion.

“Oh, please do,” I said. “You’ll recognize me—I’m the third from the right.”

A few days later he sent a message backstage at the Pavilion asking if he might call on me one afternoon with a few of his songs. Johnny approved: A. P. Herbert was an excellent person for me to know. On the afternoon Mr. Herbert visited me, Johnny discreetly took himself to the cinema. I was proud to usher Mr, Herbert into our little flat. Somewhere I had read that black was fashionable and I had had our sitting room walls done in black wallpaper covered with Httle orange butterflies. It was busy and dreadful but I thought it very smart.

Mr. Herbert was the essence of charm. He sat at our rented upright and I sang his songs. “Very good,” he said encouragingly. “By all means keep up your voice lessons.” He looked at the photographs on the wall and seemed properly impressed. “Who is that?” he asked, indicating a hazy snapshot that Johnny had taken of me on our honeymoon.

Suddenly I had to have more of a family than just me.

“My sister Alicia,” I said.

Mr. Herbert stared at it again, then at me. “Amazing! Is she your twin?”

“Oh, no, she’s a little older than I am,” I hastened to say. “But everyone remarks on the resemblance.”

He gcized at my treasure, my renovated childhood photograph hanging in a place of honor side by side with Johnny’s. “This is you, of course,” he said, to my deUght. “And this?” He pointed to Johnny’s photograph.

For a moment I was nonplused. Then I thought of Jessie and her Uttle brother.

“My brother David,” I said. “He died before I was bom.”

“Ah, too bad,” murmured Mr. Herbert, sympathetically.

On a Sunday afternoon a few days later, he came over to play songs from his new operetta. After he ran through them on the piano, he looked at me mysteriously, and announced, “I have written a poem you might like to hear. I call it, ‘The Third From the Right.’ “

“Oh,” I cried. “You’ve written something about me!”

He grinned, and began to recite:

The Third From The Right

Mr. Mumjumbo’s been telling my bumps, And it seems I’m a wonderful girl. I’m lovable, kind, ambitious, refined. And likely to marry an Earl. I’ve Culture well-marked in my forehead, I hear. And Talent for Business just over the ear, I’m sure to succeed in some brainy career Well—but why am I still in the Chorus!

I listened, enraptured:

They all like the third from the right,

I’m filling the house every night;

I could act if I once got a chance—

Well, I’ve made people think I can dance;

The public may wish us.

Just merely delicious,

But we want to play Desdemona.

I could be tragic and husky and hoarse, Ophelia, perhaps is my part— If the manager thinks I’m a butterfly minx, I can tell him I live for my Art. Sometimes I dream that I’m taking a call. Catching the showers of flowers that fall, 78

Or acting as Judge at a fancy-dress ball— But I wake and I’m still in the Chorus.

I said, with emotion, “You know just how I feel!” Mr. Herbert, enjoying himself, recited the last stanza:

They all like the third from the right,

It’s a pity my eyes are so bright,

For nobody sees that I’m deep,

A kind of volcano asleep.

Don’t praise my figure,

I wish it was bigger,

For I want to play in Grand Opera,

A few weeks later “The Third From the Right” appeared in Punch. I was immortalized by one of England’s most distinguished writers in one of England’s most distinguished magazines!

The call came at eleven a.m. Mimi Crawford was ill. I would go on in her stead!

My heart started pounding. I said to myself, don’t get frightened. Or you won’t be able to do it when the time come^. I rushed to the theater. There Mr. Ring, the stage manager, grabbed my hand. “Thank God, I thought you’d never get here!” He led me to Mimi Crawford’s dressing room. Wardrobe women, pins in their mouths, swarmed about me, fitting Mimi’s clothes to me. I tried not to think of the ordeal awaiting me—to go out on that stage alone, to stand alone in the brilliant spotlight, singing, dancing, acting, with every eye on me, - alone. I dared not think about it: once I let my heart beat too fast, it would choke in my throat and not a word come out. And I thought, this is Johnny’s triumph, because the stage had not been my idea, it was all Johnny’s.

From the wings I heard the brief announcement: “Miss Mimi Crawford’s part in this performance will be taken by Miss Sheilah Graham,”—and the audience’s sigh of disappointment.

Then Mr. Ring’s tense voice: “Sheilah, ready—two minutes . . . one minute . . . thirty seconds ... on stage!”

There was an enormous fanfare of music as the overture began, ana I hurried out to stand, trembling, behind the closed curtains. I had to make a grand entrance—come from behind the curtains, part them, and stand there in the spotlight striking a pose, my arms outstretched, my head up—then go into my song. As I stood waiting for my cue I thought frantically, suppose my hands become paralyzed! But no. It was do or die, and I did it. At the right moment I parted the curtains and stood there, in a golden haze, my head up, smilmg, knowing only, don’t be frightened, there is no failure, give it everything you have, don’t tremble, give them everything — There was a wave of applause, a chord from the orchestra, and my voice rang out, clear as a bell:

The voice of the desert is calling me, It constantly calls to me . . .

Then the applause came beating up from the stalls. I rushed back to change. “Jolly good!” from Mr. Rmg. “Keep it up!” He hovered over me.

Nothing could go wrong that night. I had no clear idea of what I was doing. I was simply imitating Mimi Crawford down to the tiniest toss of a curl. I moved m that golden haze, I was bathed in applause, in the great wave of affection and admiration flowing to me from the audience.

Unbelievingly I read my first notice in the newspaper the next day: CHORUS GIRL LEAPS TO FAME^ this, under my picture. And the story accompanying the photograph began: “Her fair beauty and dulcet voice enchanted a packed house at the Pavilion last evening…”

For seven delirious performances, until Mimi Crawford returned, I played her role. In the midst of it a starry-eyed Johnny brought me the Daily Express for August 28, 1927. There was my picture agam, and under it the words:

A BORN ACTRESS—

Miss Sheilah Graham is playing a great success in Miss Mimi Crawford’s part in One Dam Thing After Another. That gifted young lady was not even a recognized understudy but stepped into Miss Crawford’s part without even an hour’s rehearsal. So successful has she been that she has been promised a speaking part in the next edition of the revue, although she is only a beginner… Mr. Cochran is delighted with her aptitude and told me tonight that he considers her one of the most promising young actresses on the London stage.

It was incredible. I read it, Johnny read and re-read it. He said, “I knew it. Nothing can stop you now. Nothing!”

Mr. Cochran sent me a congratulatory note and enclosed a ten pound bonus. There was also an invitation to call at his office, high above the stage.

“You’ve done very well, my dear,” he said. He was in high humor. I had heard that understudies were often offered leads in touring companies. I risked everything. “I’ve been offered a chance to go on tour, Mr. Cochran. But if there’s any chance of getting out of the chorus for good, I’d like to stay with you.”

He came from behind his desk and putting a hand under my chin, he tilted my face up to his, and said softly, “My dear, of course you’re going to stay with me. I will make you a star.”

I thought, despite my gratification, Oh dear, how am I going to handle this? Mr. Cochran was a kind man but he had a reputation with girls. This man can make me a star. How far do I have to go for it? I did not want Mr. Cochran to be more than an employer to me. I walked home with a cold weight in the pit of my stomach.

A week later he invited me to join him and a few friends—among them, Frederick Lonsdale, the prominent playwright, and Lady Diana Cooper—for lunch. I went, with Johnny’s blessings. At last, I was moving in the right circles! “Watch and listen.” he counseled me.

I was agonizingly self-conscious all through the meal. Oh, to be like these people! To speak easily, to be accepted—even more, to be famous! Yet, as I watched and listened, I was strangely disappointed. I sat silent, smiling politely, listening intently, and thinking, is this what they talk about? I had thought such distinguished personalities spoke in lofty, elegant language about matters of the highest importance. But Lady Diana at this moment was saying to another woman, “Did you see what Iris was wearing last night?” And another guest remarked, “God, if I ever hear Louise tell that tired story about the policeman and the American—” 1 listened to them and learned what small talk was. It was laughing gently and saying, “Weil, this is a funny piece of cheese, isn’t it?” And, “If I don’t have my hair done after lunch, I’ll be wretched all day—” They spoke about their latest marriages and divorces, about their diets and ailments. I thought, so this is what you talk about when you have nothing to say.

And it came to me, I can do this. Even if I stopped school at fourteen and can’t open my mouth lest I show my ignorance, or get my me-uens wrong, I can do this. All you need to get by, even among the accomplished and the famous, is to speak casually about the trivial— or scomfuUy about anybody. That is all you need, once you are part of this charmed circle. I can become part of it, I thought.

I felt sure of it when, at the close of One Dam Thing After Another, Cochran signed me to a three-show contract with a speaking role in his next production, Noel Coward’s T/2/5 Year of Grace. I would appear with Jessie Matthews, Tilly Losch and other stars. My contract provided for ten pounds a week with an increase to twenty by the third show.

I was able to help Johnny enormously with his mounting debts. I could only marvel that this good fortune had come to me. I was nineteen, and making more than I had ever dreamed of.

Johnny was very proud. “I told you,” he said. “By Jove, they’re beginning to appreciate you. Now the world will see in you what I’ve always seen. There’s no limit to what you can do!”

Next chapter 11

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).