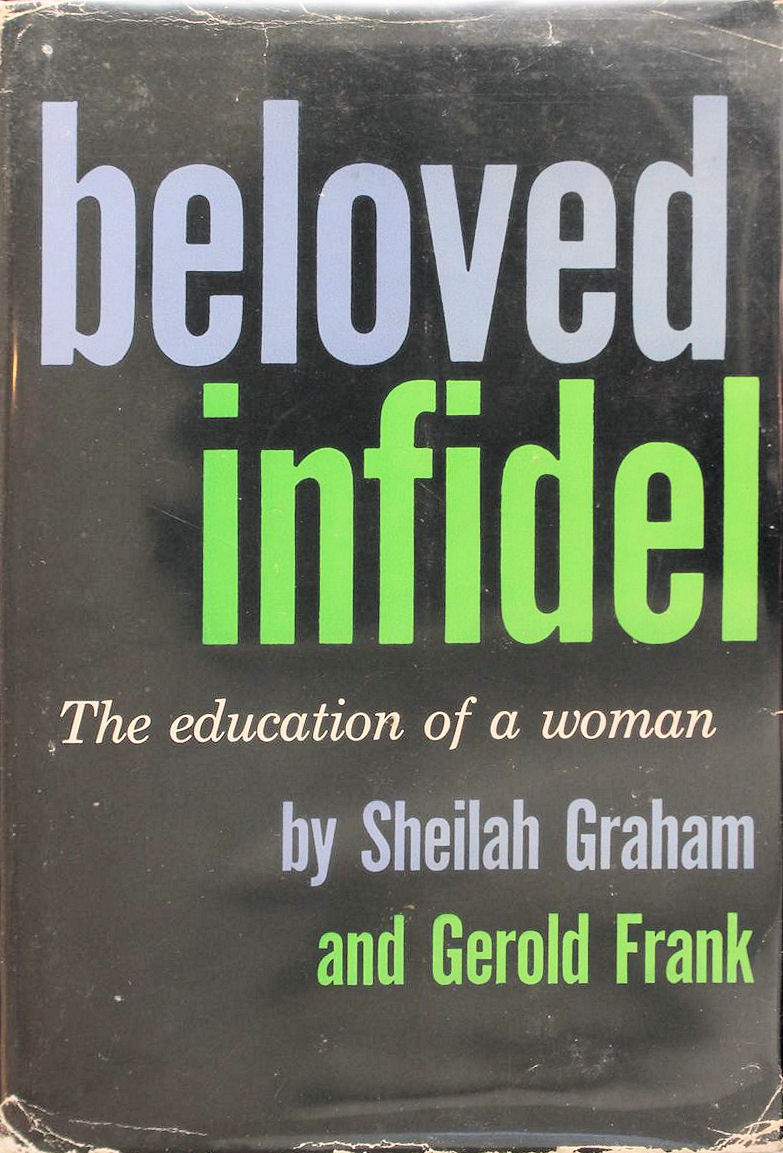

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Mr. NOEL COWARD snuffcd his cigarette out. “No, no,” he said, impatiently. “That’s not the way to do it!” He hurried on stage. “Let me show you.”

I had never expected to meet Mr. Coward. But the principals of This Year of Grace were rehearsing in a Soho hall when Cochran walked in with this slender, nervous, cigarette-smoking gentleman whom I instantly recognized from his photographs. I became flustered. He’ll see right through my sham and know that I’ve had only a few months of dancing and singing lessons. But I had to go ahead, and while he and Cochran took seats in the empty stalls I went through my role with a male lead. r It was then that Mr. Coward bounded up on the stage. ^ “Here,” he said. He took me in his arms. “Now, look at me as though you were disdainful of me—”

I was not sure what disdainful meant, so I promptly turned my most dazzling smile on him.

“No, no, no!” His voice became a thin quaver. I wanted to cry. He threw his hands up and looked at Cochran. I thought, in despair, he knows I’m a fake.

Cochran, from his seat, said quietly, “Sheilah, you can do better than that.”

We tried again and this time, instead of casting a withering glance at him, I gazed at him soulfully. “Oh, my God,” said Coward, and gave up. “Let’s go on to the next scene.”

Here I was to sing:

I am just an ingenue,

And shall be ‘till I’m eighty-two,

At any rude remark

My spirit winces,

I’ve a keen dramatic sense,

But in girlish self-defense,

I always put my trust in princes.

I was to have burlesqued the song, lisping the words in wide-eyed innocence. Instead, I sang it seriously. Years later, walking on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, I knew exactly how I should have sung it; and when Noel Coward came to Hollywood I sang it for him and he laughed, “Yes, just the way it should have been done.” But now he sat glowering in the stalls; and when I glanced in his direction a few moments later both he and Cochran had gone.

We were to open in Manchester. I was tense and nervous. In one number I had to pirouette on my toes, but my insteps were too weak. I could not carry off what had taken others years of practice. Under the long ballet skirt which mercifully hid my bent knees, I staggered about like a drunken man.

Opening night my experience was almost a burlesque of every amateur’s nightmare. I was to enter doing high kicks across the stage. The music swelled: I made my entrance: the audience gave me thunderous applause. I glowed with confidence. I’ll show them. I kicked as high as I could—my left foot slid from under me and I sat down hard, on the stage.

The applause turned to laughter. My face burned as I scrambled to my feet. Now I couldn’t get back into step with the music. The laughter turned to roars and shrieks —I staggered across the stage, making half-hearted at-temps to kick, my smile frozen on my face, unbearably humiliated, saying to myself, you can’t cry, you can’t cry, you have another number, you can’t cry.

Then I was off, rushing into the wings to change to my next costume. Suddenly, I saw stars: I had crashed into a huge, papier-mache rock backstage, used for a Lorelei number. The noise echoed through the entire theater.

That did it. I lay there and cried and cried. Even Cochran, who put his arm comfortingly around me, could not persuade me to go back on stage until the grand finale.

But when we opened in London, three weeks later, luck was with me. This Year of Grace was a smash hit, and I with it. The reviews were flattering; my pictures appeared in all the newspapers: “Sheilah Graham Laughs” . . . “Winnmg Her Way” . . . “Little Sheilah Graham, the chorus girl who has had a romantic rise to fame.” And after a few weeks, “Sheilah Graham, one of Mr. Cochran’s most charming young ladies, who scores so brightly in This Year of Grace”

And as my luck held, my quandary grew. I was married, my marriage was a secret, and I was going out with men. Sir John Carewe-Pole had been the first. Now Cochran, who exhibited me as his newest star, was taking me out to supper. And many of his friends were asking to meet me. Other invitations came. It was impossible to be starred at the Pavilion without finding yourself surrounded by gallant admirers. Night after night its front boxes, which extended onto the stage, were filled with men in blazing white shirt fronts and tails, who could reach out and touch you if they wished when a whirl or a step brought you next to them. Sometimes the Prince of Wales sat there; but always these boxes were occupied by the most glamorous, the most charming and elegant men in England.

One night two handsome men in the box kept their eyes on me. As I danced by I heard distincdy, “Hello, you pretty little ewe lamb.” I smiled and danced on. A week later the box was taken by the same men. Again the odd salutation, “Hello, you pretty little ewe lamb.”

That night, after the performance, three limousines waited to take the girls of the cast to a bachelor supper at the Savoy Hotel. Our table partners were ojfficers of the Royal Guards. We sat at a long table with magnificent food and champagne, and gifts for each of us— compacts, lipsticks, silk stockings. Presently a young man wandered over and took the chair next to me. He was introduced: Captain Ogilvy. Later I learned he was the Honorable Bruce Ogilvy, equerry to the Prince of Wales. Then an older man, blue eyed—with a red mustache through which he hissed when he grew excited—came over and sat at my feet. He was Sir Richard North, in his fifties, and our host. Both occupied the front box at the Pavilion. It had been Sir Richard who called me the “ewe lamb.” But I ignored him because I was fascinated by Bruce. He was about twenty-eight, strikingly handsome: blue eyes with long black lashes, a straight nose, a clipped Guard’s mustache, sharp high cheekbones and a languid expression that seemed full of mischievous amusement. He snorted when he laughed—I found that irresistible.

Would I come to supper again the following Thursday night after the performance? And invite five of Cochran’s Young Ladies? Sir Richard wanted to know, too, would I honor him by taking tea in his town house the following Sunday?

I had discussed all this with Johnny. We reached an agreement. Going out would help my career: it would also be a means by which I would grow and develop and learn to hold my own with the upper classes. So I accepted the invitations of Sir Richard North and Captain the Honorable Bruce Ogilvy.

I was escorted home that first night by both Bruce and Richard, one holding my right hand as we sat in the cab, the other my left. They said good-by at the door. I floated in to tell Johnny my evening’s triumph as a girl might tell her mother. I told him how they admired me, how beautiful and desirable they made me feel, how each wanted to see me again, how attractive Bruce was, that his mother, the Dowager Countess of Airlie, was a lady-in-waiting to the Queen. I told hun Sir Richard was enormously wealthy, he had great stables in Ireland and loved to ride to hounds and said he had always wished he had a daughter like me. I told Johnny how respectful, how adoring, how charming these men had been. Johnny was more than pleased. His protege was becoming appreciated in ever higher circles.

Each Thursday evening thereafter I was guest of honor at midnight suppers at the Savoy. I would open the menu to find that -every dish had been named for me: “Potdge a la Belle Sheilah;” “Poulet Polonaise a la Belle Sheilah;” “Bombe a la Belle Sheilah.” I was the ewe lamb, the sacrificial lamb, pursued by the wolves, and it was all done with such high spuits, such charm and insouciance, that it was like a fairy tale.

And I—I wanted to have everything this enchanting life could offer. I went out frequently with Captain the Honorable Bruce Ogilvy, with Su: Richard North. I danced with their friends in the Irish and Welsh Coldstream Guards. And each time I was less gauche, my accent less noticeable. My voice, which had taken on something of Johnny’s low, musical quality had now an added touch of Bruce’s quiet drawl—the hallmark of the upper classes. Now I repeated the chitchat, the small talk I’d heard when I had lunched with Lady Diana Cooper. It was more than suflacient, for there were no intellectual discussions at the Savoy suppers, nor at the other parties I attended. It was considered bad taste to flaunt one’s knowledge. Just laughter and beautiful compliments and admiring glances. Now / laughed gendy and said, “This is a funny piece of cheese, isn’t it?” Sometimes I made a humorous remark and they’d laughed and I’d think, pleased, well, I can be amusing, too.

In this world nothing was taken seriously. One afternoon I accepted Bruce’s invitation to have tea with him in his mother’s flat while she was away in the country. It was a surreptitious visit. As we sat together, we heard the front door open and close. We sat, hushed; a few minutes later Bruce tiptoed to the door and tried it—and turned to me. “Mother—she’s locked it, and I don’t have a key! How are we going to get out?” And suddenly, in a burst of mirth, “Good God, what will the Queen say!”

It was an Alice-in-Wonderland world in which Bruce could report that he had just come from the Guard’s mess hall where the Prince of Wales—he called him “Pragger-Wagger”—and half a dozen other chaps had spent the afternoon playing leapfrog over the tables. Or in which, dancing with Bruce at the exclusive Embassy Club, we passed His Royal Highness dancing with a lovely young lady. “Oh Bruce,” I whispered, “dance me close to the prince.” He did. The two men nodded at each other and H.R.H.’s eyes flickered over me. Later Bruce told me, “Pragger-Wagger wanted to know who was the beautiful blonde I was dancing with.” “What did you say?” I asked, breathlessly. “I didn’t give your name,” he replied, with a mischievous grin. “I don’t want him to take you away from me.” Who would have thought it, the Prince of Wales asking about mel

My past was as remote as a stranger’s dream. Yet once I had a narrow escape. One afternoon while waiting with Elsa for a bus, I heard a voice shout, “Lily! Lily Sheil!”

I almost fainted. I managed to turn. There, hastening toward me from across the street, held, up momentarily by traffic, was Leslie! Leslie, older, but still Leslie! He waved excitedly.

For a moment I stood paralyzed. Then I grabbed Lisa’s hand and began running. “Quick—there’s the bus coming—”

I was running, Leslie was running after me. It was like a nightmare in which you are pursued by something unimaginably evil, and no matter how fast you run you seem to be standing still… But we were at the bus, we clambered onto it, it pulled away. I clung, weakly, to a support.

I said nothing when I came home to Johnny. He was trying to forget his financial woes by writing an article on Easter eggs, which he hoped to sell to a newspaper. He had sent off many articles and had yet to sell one.

I said, perhaps a little sharply because I was still upset by my experience, “Oh, Johnny, you’re wasting your time. People aren’t interested in Easter eggs.”

Annoyed, Johnny flung his pencil down. “Well, what are they interested in, if you know?”

I thought. “Remember my first night in Punchbowl, when I came out the stage door?” I had rushed down expecting to find the little alley crowded with stage-door Johnnies in evening dress and top hats, with a bouquet of flowers in one hand and diamonds in the other. Instead, there were only two bedraggled teen-age girls waiting for the star’s autograph. “I think people would be interested in a chorus girl’s experiences.”

“By Jove!” He was enthusiastic now. “You have something there.” He rubbed his nose. “Why don’t you write it?”

I was taken aback. Yet, come to think of it, everyone liked my compositions at the orphanage. They had even been read aloud. I sat down with a pencil and a notebook of yellow paper and wrote, “The Stage-Door Johnny, by A Chorus Girl.” After my husband corrected my elementary-school spelling and grammar, we sent it to the Daily Express. I had already learned to aim for the top and the Express was one of London’s most widely-circulated newspapers.

Each morning I looked for my article to come back in the mail. Days passed. Finally I could not endure the suspense. At intermission one night I hurried to the backstage telephone and called the Daily Express, demanding to speak to the literary editor himself, Mr. Reginald Pound. Unbelievingly enough, he came on the line. “I sent you an article about four weeks ago and it hasn’t come back, I want to know if you’re going to print it.” I gave him the name.

He said, “Odd that you should call tonight. We’re using it tomorrow.”

I had to sit down. Then I came to my senses. “Tomorrow!” I almost shrieked. “That’s wonderful. Will I get anything for it?”

I heard him laugh. “I have requisitioned payment of two guineas.”

In a daze I asked, “When do you print it?”

“Tonight.”

“CouJd I possibly come down and see it printed?”

“Most certainly,” he said.

The moment the performance ended, Johnny and I rushed to Fleet Street. Though Mr. Pound had left, there were instructions to take us to the composing room and show us my story in type. I breathed printer’s ink for the first time.

That night I could hardly sleep. How magical this was! I had had a thought. I had put my thought on paper. They were paying me two guineas for it!

The next day, there was my article on the literary page, opposite the editorial page. I promptly telephoned Cochran and A. P. Herbert: “Don’t forget to read the Express today. I have an article in it.”

Everyone at the Pavilion congratulated me, particularly Mr. Cochran. “There’s quite a lot going on behind that pretty face of yours, isn’t there?” he said. Mr. Herbert came over to congratulate me and give me tips on the rules of composition. When I sat down again to write, my mind teemed with do’s and don’ts. Self-consciously, I wrote four articles, one after another—none sold. 1 tried a fifth—and when that returned, I gave up. Too many problems were now harassing me—and perhaps writing wasn’t as easy as I thought.

This Year of Grace was the first—and last—of the three shows in my contract in which I. appeared. For without knowing it, I was begirming to crumble under pressures growing too great for me.

Mr. Cochran was very attentive; still fatherly, still jolly, he escorted me frequently to lunch. When we were in cabs, he kissed me. I was in a dilemma: how could I avoid what appeared inevitable? I was anxious, too, about my part in the show: my role had been whittled down, bit by bit, as my lack of experience showed itself. I was obviously inadequate in the more difficult routines. I struggled frantically to keep pace with girls who had been dancing since childhood.

At home Johnny’s business problems, though he sought to hide them, weighed heavily. He could not hide the fact that my salary supported us. As it was, our bills were always overdue. I grew increasingly tense. I found myself on a furious merry-go-round, night and day. Morning lessons, afternoon rehearsals, evening performances, midnight suppers, a constant round of entertainment, dancing, food and champagne, and very little sleep. Exhaustion dogged me.

It was becoming harder to maintain my double life— as Sheilah Graham, escorted by Bruce Ogilvy, whom I liked more than I should, C. B. Cochran, who was most solicitous, Sir Richard North, who showed increasing affection toward me—and as Mrs. John Gillam, shopping on Wigmore Street and prevailing upon merchants to wait for their, money. I began to suffer excruciating headaches and indigestion so agonizing that it bent me double. Small as my part had become in This Year of Grace, I found myself forgetting lines and bursting into fits of uncontrollable weeping.

A song in the show ran through my mind:

Dance, dance, dance, little lady,

Youth is fleeting to the rhythm beating in your mind.

Dance, dance, dance, little lady.

So obsessed with second best,

No rest you’ll ever find…

I thought, yes, this is me—dancing and dancing, spinning and spinning faster and faster. . ..

At this point Cochran put me in a quandary.

I had prevailed on Johnny to take me to Torquay, a seaside resort, for a weekend of complete rest. “My dear,” Cochran said, taking my chin between thumb and forefinger, “wire me where you are staying. I’ll come and see you.”

After a great deal of agitated thought, how to discourage him without angering him, I sent what I considered an ingenious telegram from Torquay: DELIGHTED SEE YOU OFFICE HOURS ARE NINE TO SIX.

He ‘did not come to Torquay. Back in London I asked, a little apprehensively, “Why didn’t you come up as you said?”

He replied curtly, “I didn’t like your office hours.”

I had lost Mr. Cochran as an admirer. It did not help my peace of mind.

It was Sir Richard, finally, who brought the merry-go-round to a halt. I had lunched frequently with him at his home, a narrow, elegant, gray-brick house in which my main impression was of shining mahogany and gleaming silver, with handsome paintings and hunting prints everywhere. After coffee, Sir Richard would sit on the floor at my feet, stroking my hand and looking up at me with his pale blue eyes. “My little ewe lamb,” he would say, and kiss my hand. “I’ve never had anyone I wanted to take care of as much as you.”

Sir Richard had tiever married. He had retired from the Indian Civil Service and he spoke often of the fact that he had no family, which helped explain the suppers and entertainments he gave so lavishly for young people. He had sent me gifts, enormous quantities of Fortnum and Mason’s most expensive prepared foods—cooked salmon, smoked trout and ham, plover’s eggs—and once a crate of grapefruit postmarked, “Florida, U.S.A.” arrived for me backstage.

On one visit to his home he showed me his collection of prints. He paused in front of a beautifully intricate forest scene, all trees, branches, vines, and leaves. “This is a most unusual French print,” he said. “How do you like it?”

Putting on my most intelligent expression, I examined it on the wall. “Oh, it’s lovely.”

“Look close—do you see anything interesting?”

I shook my head. “But look, my dear—” and there, amid the branches, faintly etched, were naked men and women making love.

I drew back, repelled, and stole a fearful glance at him, but he was smiling down quite pleasantly at me. I thought, isn’t it strange when love can be so beautiful that this man should find enjoyment in something like this? Yet he was invariably kind to me, and remarked often on his loneliness. Once he said, smiling, “I’d Hke to adopt you,” and I laughed. The afternoon came, however, when he said it most solemnly. “I mean it. I want to adopt you, legally. You will be my daughter, Sheilah.”

I didn’t want to be his daughter. When he pressed me at a moment when I was growing more and more distrait, I suddenly blurted out, “You can’t. Sir Richard. You can’t. I’m married.”

There, I thought—it’s out. The masquerade is over.

He blanched, then his face reddened. My words seemed to drive him into a strange excitement. He began to hiss through his mustache. “That doesn’t matter. You must divorce at once.”

“Oh, no no no,” I cried. “I couldn’t do that.”

He went on eagerly as though he had not heard me. “I fan arrange it easily. I will be the corespondent—”

I burst into tears and could not stop. He grew extremely distressed. “I’m sorry—I won’t insist if you don’t wish. Think it over—” He seemed so genuinely upset that I sobbed everything out to him—the weight of concealing my marriage, the struggle to keep up with the girls in the show, my headaches, my indigestion, my exhaustion. He said, “I will have my physician see you at once.”

His physician was an associate of Sir Henry Simpson, physician to the Queen. I was examined; Sir Henry himself was called in consultation: I was suffering from extreme exhaustion and was on the verge of a complete nervous breakdown. My indigestion came from an inflamed appendix which must be removed at once. I must leave the show immediately and enter a nursing home. Sir Richard would take care of the expense.

The verdict came as a relief. At last I would be out of this spin. I would be cared for. I entered a fashionable nursing home off Harley Street and Sir Henry performed the operation. Later, Sir Richard said, “You must go to a warm climate to recuperate. I am going to send you to the South of France.” When I protested I could not allow him to do so much for me, he brushed my protests aside. It was his pleasure to be able to help me. I could take my husband with me and remain until I felt strong again.

At the Hotel Eden, at Cap d’Ail, in the South of France, I marked my twenty-first birthday with Johnny. He was unhappy, humiliated, resentful—yet he knew we could not afford to foot the bill. “Business is going to get better,” he said. “I’m sure of it.” He calculated the cost of the doctors, the operation, the nursing home, the hotel, and entered the sum in a little book. “I’ll pay him back very soon,” he said.

Who could divorce Johnny?

Yet, Sir Richard had come close. My marriage to Johnny was slowly becoming a marriage in name only. I am sure that this contributed to a good deal of my emotional distress. For Johnny had virtually become the affectionate elder relative we pretended him to be: father, mother, brother, confidant. Despite myself, I had begun to long for a husband of my age who would be fiercely possessive, jealous of every man—the lover, not the patron.

The free, uninhibited life of the theater, too, underlined the lack in my marriage. Here love was an enormously exciting thing, a volcanic thing of impulse and emotions run riot. In this unrespectable, impulsive, impassioned world, people were always in love—they kissed and caressed openly; at any moment backstage, as you rushed down a stair or dashed to your dressing room, you came upon a couple in an embrace so close that it seemed nothing could tear them apart.

I had always thought kissing was secret, in the darkness of a garden arbor, in the back of a car, in the privacy of your apartment. In the theater, love was love in the great romantic tradition—you dared all, you gave all without thought of cost or consequences. It was unbearably exciting, a bright, glittering, overwhelming experience—and nobody said, “This is wrong.” And when a love affair was over, when the man left as he must, the grief, though overwhelming, was exciting, too. This was the ecstasy of being young and unrestrained, of being gloriously responsive to the quickening of your pulse, to the inviting eyes and proffered hearts of the handsome men who courted you. From all this, to return to Johnny with his problems, to Johnny, who, however sweet, was more like a fatherly counselor than a husband…

Next chapter 12

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).