Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER NINE

It was 8:00 a.m. The morning sun shone brightly through the bedroom window of the cozy service flat we’d taken in Oxford Street. Johnny slept peacefully. I rose, dressed, extracted two shillings from the loose change he had left on the dresser, and slipped out. I was a lady of leisure. For the first time I had nothing to do but enjoy myself. As his wife, Johnny made clear, he could not permit me to work in the oflSce any longer.

I sauntered through the streets. Mrs. John Graham Gil-lam! I rolled the name on my tongue. Even after a month I was not used to it. Wife of Major John Gillam, DS.O. A woman of position. I stepped into a candy shop, bought fourpence worth of toffee and strolled on, sucking on it.

I was happy. To be sure, there had been one difficult episode—Johnny had been reluctant to break the news of our marriage to his sister. I realized that he feared her, far more than I had known. Yet she would never forgive us if she learned it elsewhere. Would I, Johnny had asked the day after we returned from our hone\Tnoon, pay a call upon her and tell her? He was sxire that I could win her over.

I had been afraid but, as always, when I had an unpleasant duXY to do, I did it. I prepared carefully. I wore a conserv^ative suit, little make-up, brushed my hair severely back, and armed with a discreet bag and quiet, elegant gloves, I called upon Mrs. William Gillam AshtoiL Johnny rehearsed me. saying unhappily, “I shouldn’t be sending you, you’re so young, but I know that when she sees you she’ll be captivated as I was—”

My heart pounded as I rang the bell of her flat in a quietly expensive apartment house in Knightsbridge. A prim little maid ushered me inside. I waited in the drawing room, sitting on the edge of my seat. Presently a door opened and I recognized the woman who had hung so proudly on Johnny’s arm when he emerged from Buckingham Palace with his D.S.O. I rose. “I’m Lily Sheil from the ofi&ce,” I said.

She held out her hand. ‘*Oh, yes. My brother has spoken of you.’’ She told me to sit down and then took an armchair and looked at me inquirin^y.

The speech I had rehearsed vanished completely. I didn’t know how to begin. I said, falteringly. ‘T hope this won’t—” I was stammering—suddenly all Cockney in my attempt to be elegant—so that I heard myself say. “I ‘ope this won’t come as too gryte a shock—” I saw her grow tense, her hands begin to grip the arms of her chair. “John and I were married last Saturday.”

She exclaimed, “Oh, no!’’ and burst into tears. I didn’t know what to do. I got up aw^kwardly and went to her as she wept. ‘*Oh, well it isn’t that awful, really it i^n’t—” I said, consolingly. I patted her on the shoulder as though she were a child. I had no idea what I was doing. “I’m going to make him a good wife, I anL Don’t cry, please don’t cry—”

She looked up at me through her tears. “Ill never see him again as long as I live and you can teU him that.” She had control of herself now. She blew her nose. ‘T don’t blame you. I blame him. You know he’s going bankrupt, don’t you? He won’t get another penny from me.’’

I said, “He’s very unhappy. Mrs. Aihton, he doesn’t want to hurt you. He loves you very much.”

She rose, near tears again. “You can tell him this for me”—by now her voice became a scream—”I v^iQ never see him, I am finished ^^ith him. If he wants money let him go bankrupt! He has made his bed, let him he in it.” She turned her back and hurried out of the room.

I picked up my bag and gloves and left.

Johnny was most upset. Now I had to comfort him,

“Don’t worry,” I said. “Somehow we’ll manage without your sister.” He smiled at me. “Oh, I’ll make it up with her sooner or later,” he said. “Of course we’ll manage. It’s spring, I expect a first-rate season—” He rose, fuU of vigor. “By Jove, you’ll see!” I kissed my Johnny.

Now, still sucking on my toffee, I passed a fruiterer’s. Bunches of huge black grapes glistened in the window. I promptiy bought half a pound and munched them as I walked. It was so glorious to indulge yourself. Fresh fruit—a delicacy we rarely received at the orphanage— still overwhelmed me. For the rest of my life I would never be able to get enough.

I stood looking into a familiar window. WE RENOVATE YOUR ANCESTORS. Johnny had many family photographs to decorate the walls of our flat. I had none. I remembered the faded snapshot of myself that had been found in my mother’s purse. I recalled Johnny’s adorable childhood photograph. Just then my eyes fell upon a pair of identically framed photographs, in color: someone’s children. Suddenly I was inspired. Why couldn’t I have my snapshot renovated, then colored like Johnny’s?

Later that day I hurried to the engraver with both photographs. Could he renovate this little girl? And match her to this little boy? And instead of the cheap, high-necked apron, dress her in fashionable clothes of the time? And in color?

He nodded. “We’ll keep the head, fix up the hair, put a nice dress on the body. \fVe’ll have her on a chair instead of a table—you just leave it to me.”

I asked, “Wouldn’t a rich little girl of that time be holding something more elegant than a wooden spool?”

He pursed his lips in thought. “How would you like a flov/er?” he asked.

A week later I emerged triumphantly from his shop. Here was a lovely, antique-framed photograph of Johnny, a blond-haired little prince of a boy. And here was a photograph, identically framed—to all intents taken by the same photographer—of me. I sat, not on a table, but an expensive elaborately carved chair. I wore a fragile blue frock with puffed princess sleeves, my hair was blond and in curls, my eyes were blue, and in my hand I held a daffodil. In the original photograph the comers of my mouth drooped unhappily: now, by the magic of dress and background, I appeared pouting and petulant, as might be expected of a disdainful and aristocratic little girl.

“A topping idea!” was all Johnny could say in admiration when I showed him the photographs. He watched as I hung them side by side. I gloated over mine. I still might not have photographs of my ancestors, but now proof hung on my wall, for all to see, that I had been a well-kept, well-tended, pink-and-white little girl of gentle birth.

Johnny thought it commendable of me to try to better myself. “There’s no telling what heights you’ll reach,” he would say. “There’s nothing you can’t achieve if you set your mind to it.”

I believed him. But what was it I wanted to achieve? Those first few months I was content to explore London, to buy on impulse whatever sweets I saw and, in the evening, to window shop with my handsome husband at my side.

One evening, as we passed a milliner’s window, I stopped and exclaimed, “Oo—er! Wot an ‘at!” Johnny actually winced. “Lily,” he said, almost sharply, “We’ve got to do something about the way you talk.” I was on the edge of tears. Was he ashamed? Was he humiliated by my speech, now that I was Mrs. Gillam? He had found it amusing before. “Look, darling,” he began again, kindly, “You will be meeting people now and I don’t want you to be embarrassed. Don’t ever say ‘oo-er!’ or ‘lum-me!’ Say nothing unless you can start the sentence from the beginning. And if you say something, make a comment that reflects what you think. Not, ‘Wot an ‘at!’ but, ‘Isn’t that a beautiful hat!’ or,”—his good humor had returned—” ‘I’d love to have a hat like that.’ “

He was right. I thought, when I meet his friends, one wrong word and I’ll give myself away. My renovated photograph will be ridiculous then.

I brooded about it, the more so because my idleness was suddenly beginning to bore me. Even unlimited toffee had begun to pall. Except for the weekends when we went to Brighton, where we hired horses and Johnny taught me to ride, my days seemed to pass with maddening slowness.

I tried to hide my dissatisfaction, but Johnny came home one day to find me crying. “I’m so lonely,” I wailed. “I don’t know what to do with myself.”

So it was Johnny who came up with the proposal— again, one of his characteristically breath-taking gestures —suppose he were to enroll me in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art? Kenneth Barnes, the director, knew Johnny from the Birmingham Repertory. A speech course would work wonders for me, Johnny went on enthusiastically; and though he failed to make a stage career, why couldn’t I? “You’re clever, you’re beautiful,” said my champion. “Why can’t you be trained for the stage?”

I was thrilled. I could hardly believe him. Yet, if Johnny was so confident, perhaps I could become an actress. I might even earn some money to help my husband pay his debts. For though Johnny had avoided the bankruptcy his sister had predicted, he was still in financial straits. More than onge I had come home to find an ultimatum from our landlord about the rent and a distressed Johnny: “You’re so persuasive—will you go and see him?” I had gone to the landlord and won an extension.

I applied at the Academy the same day as a plump, clumsy man in his late twenties who seemed even more inept than I. In the anteroom waiting for his interview he sat down on his hat. Later, ready to leave, he suddenly clapped his hand to his head—where jvas his hat? —and began looking everywhere, only to find it, crushed on his own chair. Red-faced, he snatched it up, glanced furtively this way and that and, apologetically, sidled out while everyone tittered. But after he gave his first reading in class none of us tittered at Charles Laughton. He was the Academy’s star pupil.

Even today I do not know why I was accepted. I had no dramatic ability, I was inordinately self-conscious and absolutely terrified to open my mouth. I can only imagine that Mr. Barnes was obliging Johnny.

My most painful ordeal came in a drama course taught by Nancy Price, a distinguished character actress. Each student was to deliver a brief speech from Romeo and Juliet. When my turn came I rose and launched into Juhet’s lines:

O, swear not by the me-uen, th’ inconstant me-uen. That monthly changes in her circled orb—

Miss Price spoke up shaq^ly. “Mrs. Gillam, please. It is not me-uen. It is moon. Say ‘moon.’“

I said. “Me-uen.” Under stress my accent grew worse.

Miss Price shook her head. “Say, ‘It is noontime.’ “

I said, “It is ne-uen time.”

“Really!” Miss Price was growing annoyed although she knew that a Cockney accent is almost impossible to eradicate. She ordered me to stand before the class, made up of some thirty supercilious young men and women, many of them university graduates, and repeat, “Moo— moo—moo.” I was on the verge of tears.

Later, in Johnny’s arms, I wept. “Now, now—” he comforted me. “We’ll practice.” He had me stand in front of the mirror and go over my most troublesome vowels. Again and again he drilled me. “You open your mouth too widely,” he said, finally. “Have you observed well-bred people when they speak? They hardly move their lips. Try it.”

Though this helped, I had the greatest difficulty. Sometimes my speech became too refined. One day I heard myself say to Laughton, who had been away ill, “I do hoop you feel better—” I wanted to sink through the floor.

In one class I played the Queen to Laughton’s King, in Hamlet. I was so impossible that I was replaced after one run-through.

The only course I did well in was miming. I played the rear end of a bucking horse and because no one saw my face and I had no lines, I managed to be quite funny.

At the Academy I learned about make-up. I learned how to enter a room, and I did improve my speech. But it was a wretched time. After my Hamlet fiasco, one girl said, “Mrs. Gillam, with your pretty face you shouldn’t attempt Shakespeare—you ought to be in musical comedy.” I smiled and took it as a compliment but I knew she meant, “With your ‘me-uens’ and ‘ca-ows’ you’re ridiculous trying to do Shakespeare.” The farce ended after three months when I received a severe note from Mr. Barnes which closed with the warning, “It is imperative that you improve.”

To Johnny I said, “I won’t go back. It’s better to quit than be thrown out.” Maybe that girl was right, I told him. I might do well in musical comedy. After all, I was good at miming, I loved to sing and dance—and everyone said I was pretty.

My husband agreed. It would be most helpful if I could get a stage job and bring money in—most helpful. I took a long look at this man I had married. He was sweet, adorable, generous—but my future would be precarious if I trusted it to him. I must prepare for some kind of career to help us both.

Johnny optimistically borrowed more money from a loan company and I immediately enrolled for lessons in ballet, tap dancing, and voice. Furiously I studied and practiced all day, singing and dancing about the flat as I did my housework. I practiced ballet steps using the kitchen table as a bar, and squatting exercises with the bedpost as a support. At the end of the first month I announced, “Johnny, I think I’m ready for a job,” and prepared to make the rounds of the musical-comedy shows. As I was about to leave he cautioned me, “Don’t apply as Mrs. Gillam, Lily. It will hold you back. No producer wants to hire a housewife.”

“But I can’t go as Lily Sheil,” I said. “I hate it. It’s everything I want to forget.” Not even Johnny knew how strongly I felt about my name—how unmistakably it seemed to blare to all the world the poverty and squalor of my childhood, the humiliation of my upbringing.

“Well,” Johnny said thoughtfully, “we’ll have to find another name for you.” And in that moment, while I waited, he invented one. From Miss Houghton’s Sheilsy he produced Sheila, and added, Graham, his middle name. I tried it on my tongue and liked it. He wrote it on a pad: “Sheila Graham.”

We both studied it. I took his pencil and added an “h” to “Sheila.”

“Why that?” asked Johnny.

“I don’t know,” I said happily. “It just looks more elegant.”

But getting a job, even as a chorus girl, was harder than I thought. For a week I made the rounds without success. Then, at the Strand Theatre, I walked in at the right moment. Archie de Bear, whose show. Punchbowl, was to close in three weeks after a long run, had just lost a chorus girl through illness. He looked me over.

“Can you kick?”

“I can,” I said.

“How high?”

“This high,” I kicked with all my might.

“Well,” he said, not enthusiastically. “All right, you go on, Monday.” Salary: three pounds.

This was Friday. I had the week end to leam a dance routine. I rushed back. “This is it!” Johnny exclaimed jubilantly. “This is the beginning. You’re going to be a star. All London wUl ring with your fame!”

“Oh, Johnny,” I said, and we began practicing. At one point I had to be twirled on the shoulders of a chorus boy. He was to stand with knees bent, hands cupped before him close to his body: I was to run, leap into his hands, he would twist me around and up and I’d be standing on his shoulders. We practiced it in our bedroom, Johnny and I. Time and again I bowled him over and we crashed to the floor, laughing and crying. But I learned it.

“Remember,” said Johnny, as he brought me to the stage door. “Always smile. No one can withstand your smile.”

I was terrified—actually trembling with fright—but Johnny’s confidence buoyed me. He stood, a tower of strength, in the rear of the theater, where I could see him. On stage I tried to keep in step by watching the feet of the chorus girl next to me. I concentrated with great care. Suddenly I realized that my head was down and I was frowning. Oh, I’m supposed to smile, flashed through my mind. I looked up suddenly and beamed at the audience, then looked down—and never got back into step again. The dance mistress was merciless. Later I wailed to Johnny, “Oh, I was such a failure!”

“No, you weren’t,” he said stoutly. “That time you looked up and smiled, it broke the heart of the whole audience.” I was touched, though I was sure all anyone noticed was a most inept girl out of step.

Three weeks later, as scheduled, Punchbowl closed, but not before I had a new triumph. At the annual Motor Show Ball held at the Albert Hall, I won the London Theatre Beauty Trophy—a silver cup—as the most beautiful chorus girl in London. Girls were entered from every show: we danced the Charleston and black bottom, then paraded before the judges. My cup was engraved with my name, Sheiiah Graham, and the legend: BE FAITHFUL BE BRAVE AND O BE FORTUNATE. I walked home in a trance.

What now? My award filled me with confidence. Anything might be possible—if, as Johnny had said, I put my mind to it. Johnny, absolutely delighted, recalled that John Drmkwater, the playwright, whom he knew through the Birmingham Repertory, was a friend of C. B. Cochran, the noted musical-comedy producer. Cochran was the Ziegfeld of London: to be one of Cochran’s Young Ladies was to, be as glorified as a Ziegfeld Girl. Johnny, in a letter eloquently describing my beauty and talent, persuaded Mr. Drinkwater to write in my behalf to the producer. The result was an invitation to audition before Mr. Cochran himself at the London Pavilion, where he was preparing a new revue.

I hurried there bringing the music from Rose Marie, which I had been studying in my voice lessons, and my brief costume from Punchbowl. There, in the darkened theater, sat Mr. Cochran with three aides. Several other girls had just completed their auditions. When my cue came, I walked on the empty stage and launched into, “Rose Marie, I love you—”

After half a stanza one of Mr. Cochran’s aides called out: “That’s enough. Let’s see you dance.”

I danced several turns in thick silence and then, utterly dejected, almost stole off the stage. I had reached the wings when a high, thin voice which could only be Mr. Cochran’s said, “Get the name of that last girl.”

I wheeled and dashed back on stage and shouted into the dark expanse of seats, “Oh, Mr. Cochran, I’m the girl! I’m Sheiiah Graham and you had a letter from John Drinkwater about me.”

There was a silence. Then Cochran’s voice: “Will you come down into the stalls, please?”

I went down into the stalls. Mr. Cochran was portly, with a red, cherubic face and bright blue eyes. He said, “Sit down, my dear, next to me.” He looked at me ap-praisinglv. I was very round and firm and fully packed. “Well—” he began.

“I don’t want to be just a chorus girl, Mr. Cochran,” I interrupted him. “I want to be something better than that.”

He looked at me again, slightly amused. I knew I was being brash, but I wanted him to know that though I might be the most beautiful chorus girl in London, I was not a chorus-girl type.

Mr. Cochran said slowly, “I shall have a small chorus —ever}’ girl will be able to show what she can do.” On his face I recognized the look I’d leen on the faces of my customers at Gamage’s.

He hired me at a salary of four pounds a week for the chorus line of One Dam Thing After Another, a new Rodgers and Hart show. I was on my way!

Next chapter 10

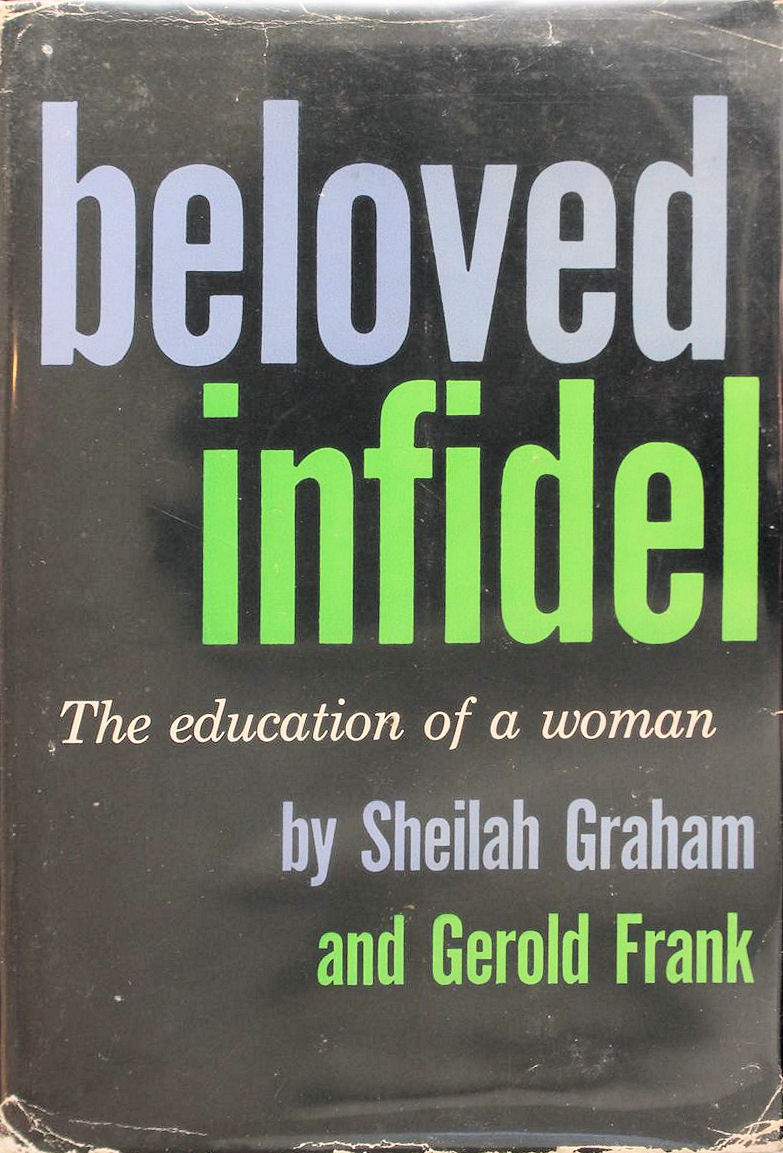

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).