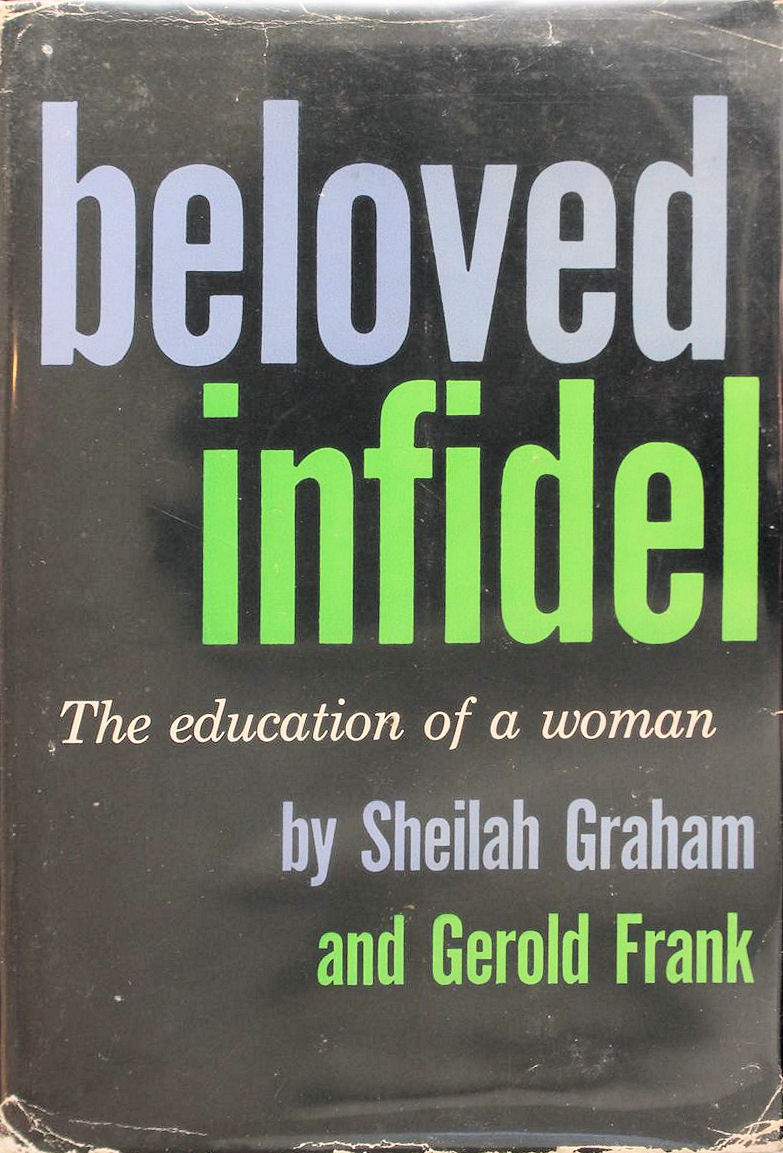

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER TWO

Suddenly, at fourteen, my days at the orphanage ended. Word came: my mother had had an operation and needed me at home. Fourteen was the earliest age under the law at which I could be taken out of school. Miss Mead, telling me the news, shook her head. “I had hoped to see you go on to win a shorthand-typing scholarship,” she said. “You have a good brain, Lily. You deserve something better. I do hope that someday you will make up the education you must miss now.”

I left her office curiously numb. Even the loss of the scholarship—the dream of every girl at the orphanage— seemed unreal. What excited me was the overwhelming fact that I was at last going into the outside.

For the next week I sewed on my “trousseau”—a complete set of clothes that the orphanage gave to every departing girl. And presently I said good by to Jessie, to Miss Walton, to Miss Mead, and walked out through the high, front gate. I was dressed in my new clothes. My hair, allowed to grow for the past two years, was now almost shoulder length, blond and thick; I wore my first hat, a navy-blue straw with a sailor ribbon hanging down the back. I carried a httle tin suitcase packed with my belongings which inclifded thick gray bloomers, black woolen stockings, and two high-necked calico nightgowns.

I had the directions to my mother’s flat written on a sheet of paper. For the first time I took a bus by myself. Again I rode on top, as with Aunt Mary. I was consumed with excitement, with anticipation, with a sense of do or die. The wind blew on my hot face and sent the ribbon of my hat fluttering straight out behind me: I put a firm hand on top of my hat and rode on, face forward, into the wind.

The flat in which my mother now Uved was in the back of a row of identical slate-gray tenements. Small and dark, it consisted of a tiny sitting room with a horsehair sofa and chair, a cubbyhole of a bedroom, and a small kitchen with a two-burner coal grate which served for both heating and cooking. During the first days at home I actually enjoyed the smallness of the rooms. After the enormous dormitory, it was cozy: you could actually feel the four sides. I was enclosed, protected. My mother, recuperating slowly from her operation, was grayer than when I last saw her, but when she took me in her arms her body was warm as I remembered it. We tried, in the months that followed, to know each other but it was difficult. There was no communication. Though I am sure she loved me, we felt awkward and far apart. I was grateful when I made a friend of Mildred Bannock, who lived in the neighborhood and worked for her sister in a dress shop.

Mildred was a plump girl with muddy brown hair who limped—and lived for dancing. She taught me how to dance and I became almost hysterical over it. This was action, excitement—this was almost as good as food! I loved to whirl and swing, to follow intricate steps as we hummed the tunes from two popular musicals, Head Over Heels and Little Nelly Kelly. At home I did the housework in fox-trot time. I’d dance over to the broom in the comer, sweep it up, bow deeply and dance with it about the kitchen, sweeping as I went. It made me forget the drudgery of housework.

One day, when I was visiting Mildred in her shop, her sister invited us to lunch. Gratefully I trotted along with them to an Express Dairy around the comer. In the tea shop we took a small table. To the waitress Mildred said, “I’ll have toad-in-the-hole.” I sat quiedy, looking about the room wondering idly, what does toad-in-the-hole mean? Then I became aware of a silence. The waitress, pad and pencil in hand, was looking at me, and so were the others. “What would you like, miss?” the waitress repeated, impatiently. I stared at her blankly and began to stammer. No one before had ever asked me what I wanted to eat. My food had been placed in front of me and I had eaten it. In desperation I finally blurted out a hoarse, “The same,” and pointed to Mildred. I let my purse shp to the floor so I could bend down and hide my crimson face. Could these giris know that this was the first time I had been in a restaurant? But now they were chatting gaily and when the food arrived—toad-in-the hole turned out to be a sausage baked in batter—we all fell to.

Then, over our tea, Mildred told me of Saturday-night dances at The Cottage, a small dance hall in nearby Bow. She knew all the boys there. Now that I danced well, she’d take me next time she went. It cost only sixpence.

When I broached this to my mother for the first time, she said no. “I don’t want you to go to a dance hall, Lily.” And then reluctantly: “Bad men go to dance halls.”

I knew what she meant. A few days before. The News of the World had a story about three English girls who had been abducted by a South American white-slave ring. I had shown the story to her. Did this really happen?

Oh, yes, my mother had said solemnly. She went on to warn me. I was getting pretty. Men would bother me. I was taken aback. Pretty? I did not beheve her. But she continued. Bad men might try to do something with me and no one would want to marry me. I’d be an old maid. They might even inject me with a drug that made you unable to distinguish right from wrong and you’d become their willing slave and follow them everywhere. This terrified yet thrilled me, to think I’d become some man’s willing slave. But I checked with Mildred, and Mildred confirmed it. My mother was right. Not only that, but a husband would always know if a man had had anything to do with you before you were married. He would always know. Mildred and I promised ourselves no matter what the temptation, we would be pure when we went to our husbands.

“But Mother,” I protested now. “Mildred goes to that dance hall all the time. If bad men went there she wouldn’t go. She’s a good girl.”

We quarreled until my mother finally agreed that I could go to the dance if I brought Mildred home so she could judge Mildred’s character for herself. Mildred came over. My mother took one look at her and gave me the sixpence for the dance. Mildred was simply too homely to be bad.

When we walked into The Cottage that Saturday night I stood there, overwhelmed. The bright, rhythmic beat of the music made my pulse tingle. Mildred, waving and calling to friends, grabbed my hand and pulled me after her. The three sides of the floor were Uned with giris sitting on benches while the boys wandered about studying and choosing at their leisure. “Sit here,” Mildred said, indicating a place on a bench, and she went limping across the floor. When I glanced around later, she was happily dancing.

I sat primly on the bench, hardly daring to look up lest my eyes catch those of a boy and I start blushing. I had never known a boy: I wouldn’t know what to say to one. In the orphanage there had been a boys’ section, but they lived in a separate building which was a world apart. I had had a secret romance with a boy, but we had never spoken. Our eyes had only met in the mirror above the organist’s head each Sunday at chapel. Each time this happened, my face had flamed, and I had looked away. Now and then, as we filed out of the room, he would cast a bold glance at me, but I dared not meet his eyes. I learned his name was Albert. At night I pretended the ceiling above my cot was a magic mirror and Albert, lying in his dormitory across the courtyard, could see me. I lay there, not a skinny, long-legged girl, but a beautiful and fascinating creature, while he watched me with adoration in his eyes, not knowing that I knew he watched me. I turned, I twisted sinuously, I raised my arms languidly over my head, I fell into all the poses of all the sirens I had seen on the screen. And night after night, thinking of Albert secretly watching me, I would smile mysteriously, promising him unimaginable delights though I had no idea what those dehghts might be. How he adored me, how wonderful it was to be admired, to be wanted…

My reverie was interrupted. A shadow fell on me as I sat on the bench at The Cottage and I saw a pair of dark trousers ending in sharply pointed shoes in front of me. I looked up. A tall young man, about seventeen, with ginger-red hair slicked back until it gleamed, was looking down at me. There was absolutely no expression on his face. “Dance?” he said, casually.

I stood up, terribly nervous, terribly grateful. We danced. The music stopped, we danced again. I had never had a boy’s arms around me. He held me firmly, he led me with great skill, and I was in a golden haze as we turned and whirled. His hair smelled sweet and familiar, exactly like the cleanser we used on windows at the orphanage, and he danced beautifully. “What’s your name?” he asked carelessly. I told him. “What’s your’s?” I managed to ask. My voice came out hardly more than a whisper. “Call me Ginger,” he said. “Everyone does.” His aplomb, his self-assurance, made me weak.

In the mi4dle of the dance he took my arm and led me off the floor. “Come into the garden,” he said. It was not a request; it was an order. We walked down a dim path into a little green arbor with two benches in it. Here it was quite dark. My heart pounded. Was I going to be kissed? We sat down and Ginger promptly put his arms around me and kissed me.

I allowed myself to be kissed. I remained completely passive. I made not the slightest move. I was as limp and unresisting as a sack. Kissing was something a boy did to a girl. After a few minutes Ginger said, “Let’s go back.” We went inside and danced.

Now dancing became my life. Ginger was a catch, the boy most sought after at The Cottage, the most accomplished dancer there. The girls swooned in his general direction when he appeared, they treated him like a king and he returned their homage with the arrogance of a king. I went to The Cottage every Saturday night. Ginger danced with me. We’d have httle to talk about to each other. Regularly he would say, “Come into the garden,” and I would follow him dutifully, and there in the darkness, sitting in the arbor, he would begin kissing me as a favor to me. I took it as a favor. I was humble. I wondered how he could have time for a clumsy, undesirable girl like me.

When he kissed me I was all aglow. For a little while I was transported far away from washing dishes and scrubbing floors, from wondering what was going to happen to me and whether I would ever be married…

It was better than any dream you could have, to be held so warmly and tightly and kissed by a boy.

Each time I came home from a dance, my mother and I quarreled. As the weeks went by, we grew more and more estranged. We fought about The Cottage, about her warnings that dancing and boys would ultimately lead to my disgrace. We fought about Mildred, who she decided was a bad influence on me; about my endless daydreaming; about my constant reading of Pearson’s Weekly and other tuppenny periodicals. Once I tried to explain how much dancing meant to me: how gloriously free it made me feel. But she only looked at me suspiciously. We simply could not reach each other.

When she grew strong enough to resume her job, I could not endure staying at home. It had become a strait-jacket. I detested the interminable scrubbing and cleaning, the marketing and cooking—everything I had to do when she was out. Why had she made me give up a scholarship for this? I might have gone on to be a typist, even a secretary.

Matters boiled over one day when I refused to put blacking on the coal grate. “I won’t,” I cried. “You don’t want me to have any fun at all. You brought me here just to make me work! I wish I was back at the orphanage!”

It was the crudest thing I could say to her. Hurt and furious, she advanced on me, her hand upraised: I warded off the blow and struck back blindly, as I had struck back at the teacher in the orphanage. I was horrified to feel the flat of my hand hit her stingingly across the cheekbone. I had never known my mother’s face was so soft, her skin so smooth.

She backed away and burying her face in her hands, suddenly burst into tears. She sat down hard on a chair and wept, her hands still over her face. I was beside myself. “Don’t cry, don’t cry,” I begged her. I put my arm around her. “Mother, I didn’t mean it, oh, I’m so sorry—”

She flung my arm away. “Go away,” she said, through her tears. “Leave me alone. Go away and get a job. I don’t want you!”

I went to the orphanage. I told Miss Walton that my mother and I had quarreled. Could she find a job for me away from home? There was one available immediately— a position as an under housemaid—a skivy—in Brighton, fifty miles from London. It paid board, room, and thirty shillings a month—about seven dollars.

Though r hated housework, I took the job. I took it because I would be free, on my own, earning money, without teacher or mother to order me about. I could even underwrite my independence by sending a few shillings home every month—and at the same time assuage the faint sense of guilt I felt.

The address to which I was sent in Brighton, which is a well-known seaside resort, turned out to be a stately, five-story house with gleaming brass fixtures and a basement gate of intricate wrought iron. I walked up the front steps and knocked timidly on the door. Presently it was opened by a plump middle-aged woman. “Yes?” she asked.

I said apologetically, “I’m the new maid.”

Without a word she swung the door v^de to let me in. “Come this way,” she said. My feet sank into thick carpets as I followed her through a spacious reception hall and up what seemed endless flights of stairs to a small sitting room on the fourth floor. She looked me over doubtfully. How old was I? I told her, nearly sixteen. She went on: “Are you strong?”

“Oh, yes, madam, I’m very strong.”

“Are you used to doing housework?”

“Oh, yes I’ve been doing it at home and I did it at the orphanage.”

She looked at me for a moment. “Very well,” she said briskly. “There’ll be nothing for you to do tonight. You may go to the kitchen now and have your supper. You are to begin first thing in the morning. I will give you your uniforms and caps then.”

Suddenly I realized I’d never thought of myself wearing a maid’s cap. I’d seen maids in the films—somehow that piece of starched white lace perched on their heads was a badge of servitude. That really made you a servant. I blurted out, “Madam, I don’t want to wear a cap.”

She stared at me. “Why not? Good heavens girl, why not?”

“I just don’t.” I would work as a skivy, I would work hard, but I felt once 1 permitted myself to wear a cap I’d be a servant for the rest of my life.

“I’ve never heard of anything so silly,” she said, annoyed. “If you want to stay here, my girl, you’ll wear the cap like every maid does.”

“No, madam,” I mumbled, miserably, looking at the floor. “I won’t.” I stood before her, head down, saying to myself, // she makes me wear it, I’m leaving. I’ll go home and make it up with my mother.

“Oh,” she exclaimed, impatiently. “You’re a tiresome girl. I really think I shall have to send you back and be done with it.”

I was silent.

Finally: “Well, for the time being, we’U let the cap go.” Now she was all business. “We’ll have to get you blue dresses to do the scrubbing in. And a black serving dress with a white apron.” When I said nothing, she asked, suspiciously, “You’ll wear the apron?”

I said, “Yes, madam, I’ll wear the apron.”

“Good,” she said. She had one more matter to settle. She led me downstairs to the basement and into a small, gloomy room. It was furnished with a round wooden table, a wicker rocking chair and a table lamp. “You’ll sleep on the fifth floor, but this is your sitting room,” she said. “Once you come down in the morning you’re not to go upstairs again except to change. I -don’t want you going up and down the stairs at all hours of the day.”

She outlined my work. Each day before breakfast I was to water the plants, scrub the basement floor, clean and put whiting on the front steps, and polish the brass fixtures. I was to do all the cleaning, serve breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and wash the dishes. I would take my meals in the kitchen. I was to have no visitors. When I left or entered the house I was to do so by the basement gate. I would have every Thursday off, after washing up the lunch dishes, and must be in the house by ten o’clock.

As she explained my duties I glanced about my sitting room. Daylight came from a single high, narrow window, with an iron grating on the outside. The window was below the pavement level and I could see feet hurrying past. As I watched, a dog trotted by, paused, and left his message on the grating. My employer followed my glance and she made a grimace of distaste. “The grating is to be cleaned thoroughly every day,” she said. “Now, you may go to the kitchen and have your supper.”

In my spare time, those first few days, I sat in my sitting room, watching the feet go by—high-heeled shoes, flat-heeled shoes with walking sticks, tightly rolled umbrellas—to whom did they belong, and where were they going so busily? Everybody but me, it seemed, had a place to go. I shouted at the dogs who made the grating a regular port of call. Sometimes I read. There were few books in the house but I found copies of Peg’s Paper, a penny weekly, and eagerly I read about the mill-owner’s noble, handsome son. Usually the mill foreman, an evil, unscrupulous type, would try to get the innocent working girl in the family way, but it all ended happily because the mill-owner’s son fell in love with her and married her. I read romances about aristocratic girls whose lives were preordained; they went to Roedean, one of England’s most exclusive schools and, after attending a French finishing school, were presented at court and invariably married peers of the realm. This was the course of their lives—always. I loved these stories.

It was Thursday afternoon, three p.m. —my first day off. I strolled on the promenade, wearing my best: my black sailor hat, a white blouse and blue skirt, a little blue coat. My blond hair, tied in back with a black bow, hung below my shoulders. I came upon a bench facing the street and I sat down, dreaming. I had seven precious hours. What would I do with them? There was always food to look forward to, ham in a roll with a glass of hot milk—that would cost a shilling. Then, sixpence for a movie ... I juggled my hours of freedom in my pocket, fumbling with the money I had there and feeUng very happy. This was the moment for which I lived, my little green oasis of independence in the great desert of housework. To work so hard and then to have seven hours of absolute freedom—it was like seven years!

The promenade was all but deserted. From my bench I could see the bandstand, empty now but alive with music on Saturday and Sunday nights when I had to stay in. A man walked slowly by and looked intently at me. I averted my face until he passed. I was excited and a little frightened. Suppose he spoke to me? I might wake to find myself on a ship bound for South America, a willing slave. The News of the World would print my picture, my mother would cry, “Oh, I warned her, I warned her—”

The put-put-put of a motorcycle broke into my thoughts. I looked up to see a young man with dark hair slowly riding by on his cycle. As he passed he smiled at me. It was a charming, contagious smile. I half-smiled back, hardly aware of what I was doing. He continued on for a few yards, then, with an ear-splitting roar of his motor, made a wide, swooping U-turn and was at the curb opposite me. Now I could see him clearly. He was handsome, and about twenty.

“Hello,” he said, with his smile. “Care for a ride?”

I thought, he certainly doesn’t look like a white slaver. The easiest thing was to nod. If I shook my head I might have to explain and I wasn’t sure what I would say. I gave the faintest kind of a nod.

“Righto!” he said. “Come on—” He instructed me how to sit sideways and how to place my arms around him. “Now, hold on tight because you might fall off—” I dutifully locked my arms around his waist. The warmth of his body, the sense of strength there, comforted me. I liked holding him. And off we went. We careened around corners and I held on, thrilled. I wasn’t afraid. I wasn’t afraid of falling off and I wasn’t afraid of this strange man. We rode until we reached the Sussex Downs, about two miles away, a vast stretch of green, rolling grass.

“Let’s walk a little,” he suggested. We stroUed in silence for a few moments. Did 1 live nearby? 1 said, yes, I lived with my rich aunt in a big house and I told hira where it was. And I chattered on: “I love to take little walks, to get the air, it’s so healthy here by the sea. That’s why I was on the promenade. I get so bored doing nothing, because we have three servants who do all the work.”

He listened, smiling. Then he asked, gently, “How old are you?”

“Eighteen,” I said.

He laughed, put his arm around me and as we walked, bent down and kissed me. His kiss was gentle. We walked, until we came to grassy knoll. We were utterly alone. We sat on the Downs, the fresh, fragrant wind blowing, and he kissed me. I enjoyed being kissed and murmured to, there on the Downs, not a soul around us for miles and strangely without fear because he was kind to me and I could not distrust anyone who was kind to me. He told me about himself. His name was Ralph. He was a bank clerk, and he hoped someday to be manager, perhaps even chairman of the bank.

I said, “And when I get my inheritance won’t it be grand if I bring all my money to your bank?”

He laughed, and kissed me again, gentle kisses, and then said, “I have an appointment—I must go now.” As we walked back to his cycle I dared to ask, “Will I see you again?” I could meet him at the same time a week later. Good, he said. I must wait for him on the same bench—our lucky bench.

“I’ll take you home,” he said, and before I could think of what to say he had deposited me in front of the house. I stood there knowing I dared not use the front door. For an anguished moment I thought he would wait until I went in. But he jumped on his machine, waved and was gone. When he was out of sight I turned on my heel and went to a movie. I hardly knew what I saw on the screen, thinking, this will be my*secret life, meeting charming men, bank chairmen-to-be, making them adore me, kiss me until they expired on my lips.

Was I getting pretty, as my mother had said? I remembered the ornate, full-length mirror in one of the bedrooms. Each time I cleaned the room I had stood in front of the mirror and looked at myself. I saw a rather anxious face, round and pale, with greenish eyes and straight blond hair. I was no longer so scrawny. Slowly I lifted the shapeless blue work dress to reveal my legs. They weren’t so skinny now. My stockings hadn’t bunched for a long time. My legs aren’t bad at all, I said to myself. Could my mother have been right?

The hours dragged until Thursday. At three o’clock I was on our bench waiting. And I sat there through the long afternoon until darkness fell. He never appeared. When I rose I felt wretched and more unattractive than ever. My mother was wrong, the mirror lied. What had made him change his mind? I reviewed every word of our conversation, how he had looked and laughed, how he had kissed me, how he had said, ‘‘Good. And you’ll be waiting on our lucky bench. . .” Utterly miserable, I had my sandwich and milk and went to the cinema. The film was Gloria Swanson in Male and Female. It lifted my spirits a little. I walked out, thinking, I could have been Gloria Swanson. In the darkness I walked sensuously, slinkily, as Gloria Swanson walked. I whispered, “Oh, Reginald, I do love thee. I do. I do!”

Next chapter 3

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).