Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER THREE

How long I might have stayed in Brighton—how long I might have remained a skivy—I will never know, for after several months I had to give up my position and hurry back to London. My mother had been taken desperately ill.

When I saw her again in our little flat I was appalled. She had become gray and shrunken. She walked with difficulty and was bedridden most of the day. Only later I learned that her illness was cancer.

Our arguments were forgotten and I threw myself into the task of nursing her. I cooked, I shopped, I did the housework. I bathed my mother daily. A visiting nurse came twice a week and I followed her directions painstakingly.

Yet I was consumed with impatience and boredom. It did not help that Mildred came over often to help me pass the time. As one day merged into another, my unhappi-ness and discontent overflowed. I wanted to get away—away from the tiny flat, the duties, the frustration of trying to make my mother comfortable and knowing that she was in constant pain. It was not easy to take care of her, and my resentment was only underlined by her resignation, her lack of complaint.

I felt trapped, hemmed in, and wretched because I knew I should not feel this way. I rose each morning bitter, knowing only, I want to escape, I don’t know where.

My mother slept badly at night but usually, in the evenings, she grew drowsy and fell asleep. Then I would escape. I would put on my best—a blouse and skirt, my high-heeled slippers, and my special pride, a black taffeta hat with a huge brim which I had bought for my sixteenth birthday. It was a magic hat for I could make it match my moods. If I wanted to look mysterious, I turned the brim down to hide my eyes. If I wanted to look windblown, like Colleen Moore, I turned it up. I had begun to wear lipstick, but no rouge. Sometimes I let my hair hang long, tied behind with a black ribbon. If I wanted to look older, I put i$ up in a bun, under the black hat with its brim shadowing my eyes.

I stole out of the flat and clattered to the top of the street, a little awkward in my high heels, and waited for the No. 25 bus. This took you down Bond Street, through the fashionable West End, through the heart of London. I would be hard put to explain what I was seeking. I wanted to go where wealth and elegance were, to see the fine shops and restaurants, the stroUing ladies and gentlemen, watch the glittering limousines swish past carrying beautifully gowned women and top-hatted men —this was the West End at night to me, a place of wonder and enchantment, a place to dream in.

As I waited for the bus, the smell of hops was strong in the air. It came from a huge black brewery across the street. It nauseated me and I shuddered—the grayness, the drabness of the street, the men in sweaters and caps, some of them drunk, reeling from the pubs, the smell from the public houses.

When the bus came I climbed to the top. I rode past the great industrial and banking houses, their enormous ofl&ces all Ut up. I looked in as we went by. Through the windows I saw typists and secretaries moving about with papers in their hands. I envied them, laughing in the glow of the lights inside the offices. Sometimes I saw girls standing together, chatting, sometimes a young man, his black hair slicked back so sharply, talking and laughing with them. I thought, how glamorous, what an enchanted life that must be, how I’d love to be part of it — how sad that I had to miss it!

At Bond Street I dismounted. Now the luxury of walking slowly, enjoying each moment, looking in the shop windows, strolling down Piccadilly. I did not know that Piccadilly meant danger, that in Piccadilly strange, foreign gentlemen said hello to girls who walked alone.

Here were the rare-book shops, one after another. I looked at the lovely bindings, the maroon and gold leather. Here was an engraver’s shop and the sign: WE RENOVATE YOUR ANCESTORS. I stared at the photographs and engravings of grandparents and great-grandparents in their antique frames, the “Before,” and “After.” // only I had ancestors. I remembered how I had envied Jessie because she had a locket with a picture of a little brother who died before she was bom. I had nothing: no uncles or aunts, no cousins, no brothers or sisters, no ancestors— I’m related only to me.

As I sauntered on, my eye was taken by the exquisite dresses in the fashionable women’s shops, then up Bond Street by the glittering jewelry in Cartier’s window. I stood before Cartier’s window, dreaming. How would I feel if a gentleman said as he handed me a magnificent diamond-and-ruby necklace, “Little girl, would you like this?” If I were a great beauty there’d always be a peer of the realm to say, “You’re so beautiful, my dear, but you’d be even more beautiful if I could put this diamond necklace around your neck.” “Oh, I’m not the kind of a girl you think I am, really I’m not,” I’d protest. “I’m a good girl. But if you want to buy me that necklace anyway—” And he would put it around my neck and I would let him kiss my lips.

Now it was growing dark. In the dusk I played a game. Men were passing. When they looked at me I looked away. But now and then I dared return their glance with the slightest smile—to see what would happen. They stared at me boldly; they appeared to me to be extremely wicked men, their eyes sharp and piercing. I did not know that I was walking on a street where prostitutes walked.

I wanted the men to look at me. I played my game. Once a deep voice said clearly, “Good evening.” I gave a faceless man what I thought was a very mysterious smile and averted my eyes and walked on. It was deliciously frightening. A few minutes later I heard footsteps behind me. I walked faster. The steps kept pace. I was not too fearful for people were all about me. I stole a quick glance behind: a clean-cut young man in a gray suit was at my heels. He caught up with me. “Where are you going?” he asked, in a pleasant voice.

“Oh, just taking a walk,” I said airily, though my heart thumped wildly.

He asked, walking at my side, “May I walk with you?”

“I don’t mind.”

Wasn’t I bound anywhere at all, he asked? Charing Cross Station was directly across the street. I said “Charing Cross, to catch my train.” At the station we talked—I have no idea what about. I was in a fever. This mos happening. I had gone to catch a fish and I had it—^it was in my net! I had found a gentleman! Of all these teeming people going backw-ard and for^^ard, nobody knowing the other, suddenly I knew a face!

He would see me the follo\^ing night, he said. He’d meet me here, by this pillar, in Charing Cross Station, and we’d go to the cinema.

Next night I waited in Charing Cross Station. But it was Brighton all over again. The clean-cut young man never appeared. Oh, the agony of waiting when people are bustling to and fro, people who have desinations, who have homes and friends and loved ones to go to! I stood, wretched, not knowing in what direction to look. As crowds of people flowed about me, I tried to look as though I, too, had a destination—and I had no destination. And the a\^’ful dawning, finally, that I was not to have one. I waited for an hour, an hour and a half, then disconsolately took the bus home. What is life? I thought. Is it this dreary waiting for something to happen? To wake each morning full of hope, sure that something tremendously extraordinary will happen this day, and to have nothing happen…

Thus, in the evenings while my mother slept, I walked on the edge of adventure. Once the footsteps behind me quickened, and I slowed down until a tall man was in step at my side. I dared not look up. W^en we came under a lamp I stole a glance at him out of the comer of my eye. A great pang of fear shot through me. I was walking with a coffee-colored gentleman. But he smiled at me with great sweetness and said, quietly, “You look very young. How old are you?”

I said, “Nineteen.”

He looked at me thoughtfully.

“You know,” he said, “you really ought to be home. You shouldn’t be walking here.”

I said, “Oh, no, I like it here. This is nice.”

He shook his head. “I think you should go home.” He hailed a taxi, placed a ten shilling note in my hand, helped me into ±e cab and asked, “Where shall I tell him?”

I was so astonished I could think only, “Charing Cross Station. I can get my train from there.”

I sat in the back of the taxicab. I looked at the ten shillings, then I looked out the window at the people who had to walk, then at the back of my chauffeur. I’m riding in a taxi, I said to myself, over and over. I couldn’t quite believe it. When we reached the station I caught my bus and went home.

Then, one night shortly after seven o’clock, a middle-aged man, dapper in a gray Homburg and spats, and carrying a cane, tipped his hat and said, “Good evening.” I smiled timidly at him. He asked if I lived in that district. No, I said, I was in London for a visit. We walked together silently for a moment. “I’m about to have dinner,” he said, unexpectedly. “Would you like to join me?”

We had passed a restaurant with curtained windows concealing the magnificence within. The menu, in French, was framed ornately on the window. If only he would take me to a place like that.

I nodded. “I don’t mind if I do.”

The restaurant into which he took me was elegant, with waiters in tails moving around the ladies and gentlemen at the dining tables. I thought, there’ll be no toad-in-the-hole here. But his hand was at my elbow and we were walking away from the tables. “We are going upstairs,” he said easily. A little thrill ran through me. I had read about private dining rooms above restaurants. Edward the Seventh always took his favorites there. Upstairs we were shown into a lovely little room with a table set with gleaming silver, and a settee at one side. A waiter appeared and deferentially presented us with a menu. It was in French.

My escort turned to me. “Shall we start with soup?” I was enchanted. No peer of the realm could have conferred more flatteringly with his lady. “And, after soup,” he said, “would you care for roast chicken, or perhaps lamb chops?” I chose lamb chops. I’d never had lamb chops because they had too Uttle meat on them to be bought by any but the rich.

It was a beautiful dinner. I ate fast and with all my might. He questioned me about myself. I said I was a companion to a rich old lady who lived in Brighton, in an enormous five-story mansion. “I simply have to get out every little while and I love to come to London.” I spoke feelingly, from’ experience, and I thought he listened with great attention, smoking a cigarette in a holder and now and then tapping it gently on an ash tray. When I had finished eating, I sat back.

“Would you like coffee?” he asked. I nodded. We would take it on the settee, he said. He pulled my chair away when I arose and we sat down on the settee. The waiter returned with our coffee, which he served us on a small table, and then left.

My escort poured the coffee for me. As I drank it, I asked timidly, “What do you do?” “I’m an importer,” he said. I learned no more, for now that I had my coffee and he his cigarette, he put his arm around me and kissed me. I didn’t want to kiss him, but I didn’t wish to offend him, either, for he had bought me such an expensive dinner. “You’re a very pretty girl/’ he said. Then he kissed me again. I turned my face away when he tried to kiss me a third time, and his grip tightened on my arm. “What’s the matter?” he asked, annoyed, and he pulled me roughly to him. I was panic-stricken. With all my strength I broke away and found myself on my feet, trembling.

“You let me go!” I burst out. “You let me out of here!”

He remained on the settee, looking at me. “Why did you come with me?” he asked. There seemed more curiosity than anger in his voice.

I felt ashamed of myself. I wanted to say, I’m not that kind of a girl and I’m sorry I made you think I was. Instead I said, “I thought how nice it would be to have a good dinner.”

He looked at me coldly. “Then go,” he said, “You’ve had your dinner.” I opened the door and ran down the stairs and out into the cool air. I would not tell anyone about this. I would tell no one.

When I slipped back into our flat that night, I heard my mother’s voice, weakly, from her room. “Lily? Where did you go?”

“To the pictures, Mother,” I replied.

Even now, I wonder, who looked after me? What protected me? I played with fire. I was so vulnerable, and yet I was protected.

Sometimes I prevailed on Mildred to come to the West End and window-shop for glamor, but the fine stores and restaurants, the strolling ladies and gentlemen, did not excite her. Only once was she caught in the dream.

Wandering along the Mall, the long, tree-lined avenue that leads to Buckingham Palace, we came upon a procession of waiting limousines. Inside were the daughters of the aristocracy, about to be presented at court. The Palace was lit up and spectators were milling about excitedly. Swept up by the crowd, we peered inside the cars and exclaimed aloud at the young Jadies in their magnificent court gowns, at their mothers and aunts in diamonds and tiaras. Mildred gaped, too, but she was content in the East End. For Mildred, Saturday nights at The Cottage were enough.

It was Mildred, one Saturday, who introduced me to a brown-eyed boy with sandy hair, slow spoken and sincere, who worked in a shirt factory. His name was Leslie, and he was twenty. Leslie liked me; he became a steady caller. On Sunday nights, after my mother fell asleep, he took me to a movie. But until she dozed off, we would sit on our ancient horsehair sofa and kiss. Every little while we talked so that my mother would know we were behaving properly.

I enjoyed Leslie’s kisses. I wanted love badly—I wanted to be as close as I could to somebody else. But I had been taught that the consequences were frightening. To me, love meant babies, and Mildred had told me the most horrifying stories about women in labor who shrieked until they went mad or were found dead. Each time I kissed Leslie I was torn by this conflict— how far to kiss, not to kiss too much.

But Leslie took no liberties with me. He respected me, and he wanted to marry me. It was nice for someone to want to marry me but I didn’t want it to be Leslie. He was kind, he was dependable, but he was not exciting. He was not the West End.

My mother grew steadily worse now. She developed excruciating bedsores and sometimes when I woke at night I heard her turning and tossing. She was very brave, very uncomplaining. I had no idea how she suffered. I was so full of dreams, and my mother lay dying and I did not Icnow it.

I had no inkling how dreadful her last days were. I had never been close to her. From my sixth to my fourteenth year there had been the orphanage, and now in her extremity there was no warmth between us. I did what I had to do, but with poor grace. I washed her clothes. I helped care for her, whUe all I could think of was, there must be a better life for me than this. And when she fell asleep I escaped to the West End or tried to forget myself by going to a movie with Leslie.

One night when Leslie and I returned from the cinema, there was a note on the table. My mother had been taken to the hospital. I rushed there guiltily, and tiptoed into her ward. She lay in a bed behind screens, pale as chalk. She apologized for frightening me. I was permitted to see her only a few minutes, and then I went back to our flat. A neighbor, a Mrs. Barton, looked in on me several times a day.

I went to see my mother every morning. In a week she was brought home. Two men carried her on a stretcher to her bed. As she came through the sitting room I saw her eyes: she looked about the room as best she could, but so piercingly—at the sofa, at her clock, at the litde wicker armchair—as though she knew she was seeing them for the last time and wanted to fix everything in her memory forever.

And within a week she died.

Why could I not have been more sympathetic in her illness? She knew she was coming home to die. Why could I not have understood! But I was indifferent to her in her dying days. Years later I thought, perhaps this was how I punished her for placing me in an orphanage. But, poor woman, there was nothing else she could have done. She was ailing, and poverty stricken, and uncomplaining, all her life.

I was alone with her when she died. I sat in the sitting room, my nose buried in the pages of the News of the World, when I heard a small sigh. Almost incuriously I wandered into her room. She was half out of bed. She had fallen out. I lifted her up—it was very hard to do so —and put her back on her pillow and she was gasping.

Mrs. Barton, who had been sitting with her and had gone out for groceries, walked in as I struggled to make my mother comfortable in her bed.

“Oh, my God!” Mrs. Barton screamed. Then I saw that my mother’s eyes were closed. All at once the room was full of neighbors. Where they had come from, how they knew so quickly, I do not know. But I had the strangest feeling of being a spectator, dry-eyed, not a part of what was happening…

Then suddenly I found myself sobbing heartbrokenly, not for my mother’s death but for the death of this poor, good, uncomplaining woman who was the mother of the girl in that room.

Next chapter 4

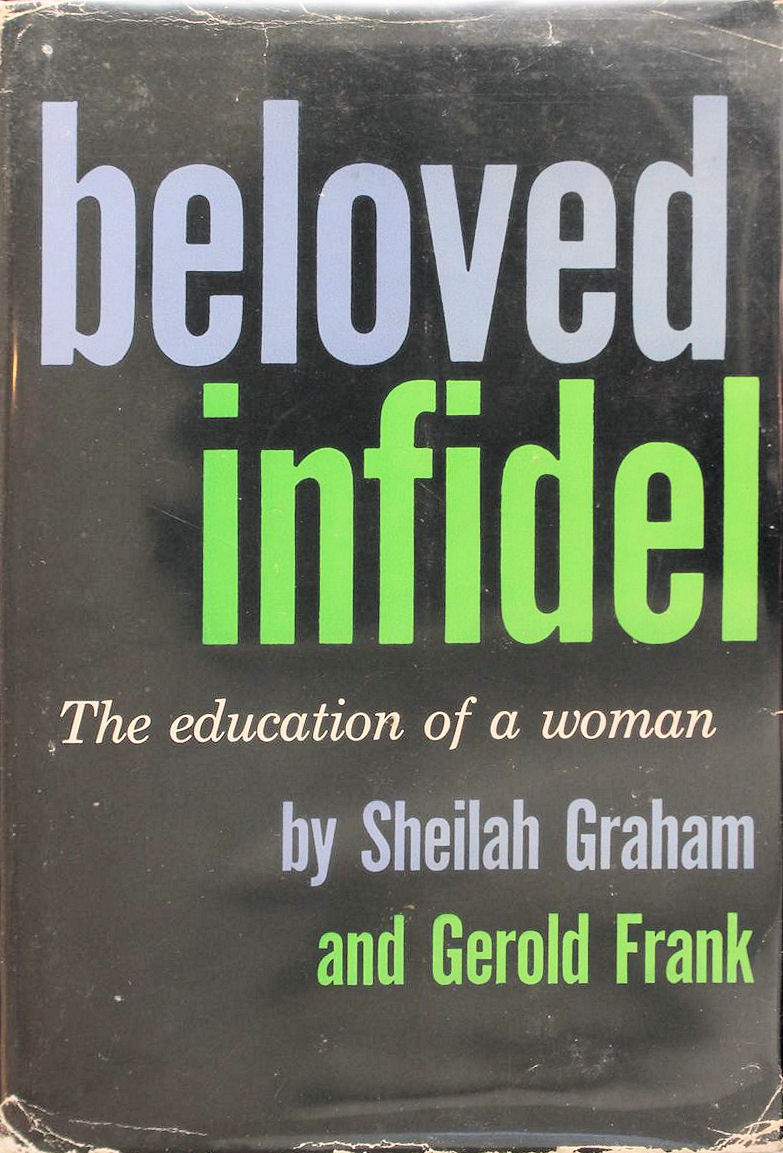

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).