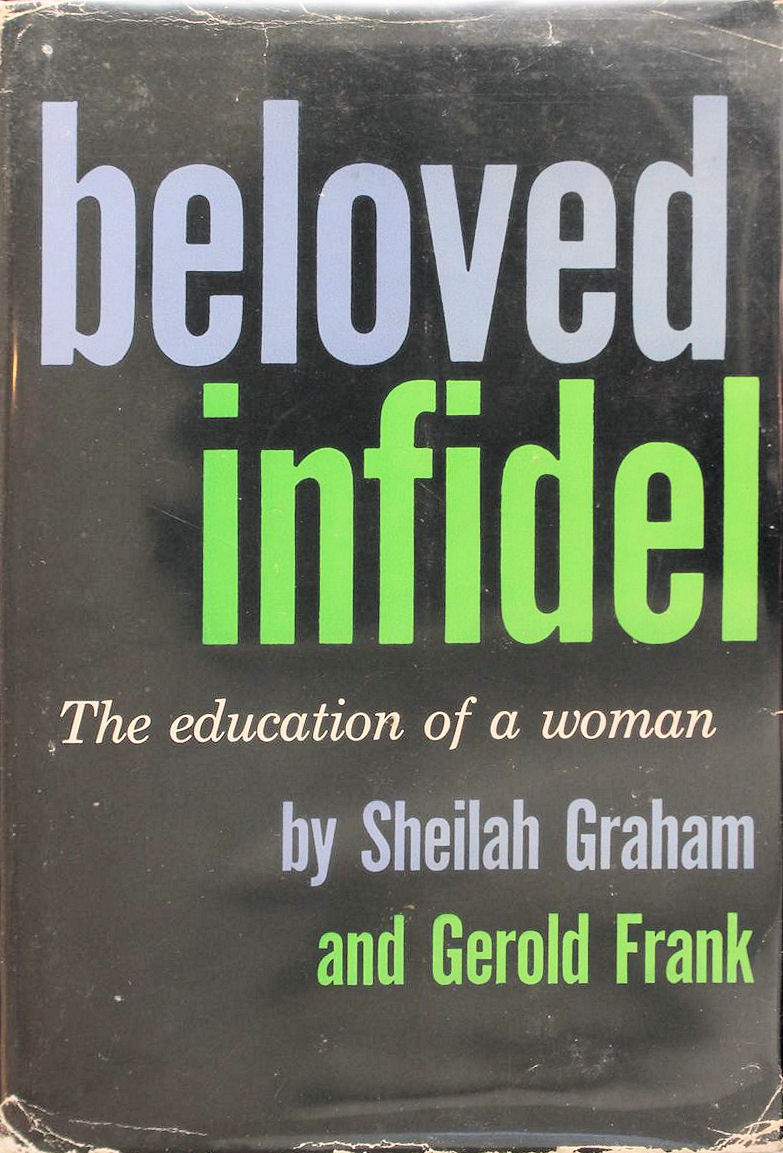

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

When I am dead, my dearest.

Sing no sad songs for me; Plant thou no roses at my head.

Nor shady cypress-tree: Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet; And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget

— Christina Georgina Rossetti

Dear Scott:

You wanted me to write the story of my life and now, so much later, here it is. I have always wondered whether I should tell it, I thought it an interesting story, yet I was afraid. I have made up so many fantasies about my beginnings, I lived a life of pretense for so long, I could not bring myself to reveal the truth. But you who alone knew my whole story were fascinated by it all — by the background I had created, the parents I invented, the name I gave myself — and so I was encouraged. “You must do your story,” you told me, and you brought a ledger and showed me how to begin by making notes of all I remembered. I might have written it then, with your help, had you lived. But you died and I had neither the heart nor mind for it. I went to London full of self-pity, almost hoping that I would be killed in the war. But instead of being killed, I lived. I married and made a new life, and to my two children I have tried to pass on something of what you taught me.

When they were younger, Wendy and Robbie, I pondered again the question of writing this book. I was still not ready — and I was frightened. What would they think of me? Of us? Would they understand how two people can be deeply in love and yet find they cannot marry? How would they feel to learn that their mother was not born to the wealth and social distinction she pretended, that her childhood photographs had been altered to show her as she had never been, that even the photographs of uncles and aunts on the walls were frauds…

But the most significant part of my story is your story, too, and this helped me resolve my dilemma. As the years passed and I read increasingly about you in books and magazines, I found myself thinking, “This is not the Scott I knew.” From those pages there emerged a man who was often a stranger to me. The man they put together from your correspondence, your books, the quick, fugitive glimpses they caught of you toward the end — this was not Scott Fitzgerald as I knew him. And others should know, too, that though Scott Fitzgerald had a demon, a terrifying demon, he had fought it and conquered it before death came to him. He did not die a defeated man.

As for my own fears, I have been able to push them aside. Little by little I have told the truth about my background to my children. They have always known about you: they know that you are something very precious in their mother’s life. Only the other day Wendy, coming upon your name, asked, “Would he have liked me, Mother?” I tried to explain to her why we were never married. I said, “I could not marry him because his wife was very ill in a sanitarium and there was a daughter he loved very much, and he could not abandon them.” I told her of your relationship to Francis Scott Key and once when she sang the “The Star-Spangled Banner” she turned to me and said, quite proudly, “I’m kind of related to F. Scott Fitzgerald, aren’t I?” And then Robbie asked, “I’m related to him too, aren’t I, Mom?” I said, “Yes, you are, both of you — in a kind of a way.” I told them that you would have liked them. Very much.

Now that they are old enough to understand and now that I have brought myself at last to face all of the truth, I can tell it. I know that I need not be afraid.

Sheilah

CHAPTER ONE

I WAS BORN Lily Sheil, a name which to this day horrifies me to a degree impossible to explain. I have not pronounced that name for twenty years. I have written it here for the first time since my childhood. My children have never heard it, nor has anyone who knows me today: they will read it on this page for the first time. Is this hard to believe? It is true. The sound of it still sends the blood rushing to my cheeks, I break out in cold perspiration, I want to flee…

The fact is that the whole of my childhood has been something dark and secret to me, and the name I was born with is tied up with the years I have kept hidden for so long. I have looked upon it as some sorcerer’s dread incantation: if 1 forget myself so much as to utter it, in a flash everything I have so carefully built up will be destroyed, the present will vanish and I will be once again what I was. Even now it is a struggle to tell the truth about my past…

It begins with a bus ride. It is an open bus, in London, and we are atop it. Aunt Mary and I. I had never ridden in a bus before. I was six, and excited, because I was bound for my new school.

“You’re so lucky to be going there,” Aunt Mary was saying. ‘They do treat little girls so nicely—”

I nodded but I was not listening. It was late afternoon of a wintry London day in 1914 and I drank in hungrily the sights and sounds of the city, the people moving in the streets, the flashing signs on the huge buildings as we roared by. I stared at one, transfixed: it was a very carnival of color, spelling the word BOVRIL, letter by letter, first red, then blue, then white. When it flashed on, it painted all the street in red, then blue, then white; and when it blinked off, the street, the houses, the roofs all whisked back into mysterious shadow.

I thought, I’m going to a place where I’ll have a proper bed, I am. And I was thinking of that when the bus stopped. I clutched my wax doll in one hand and with the other in Aunt Mary’s, we descended from the bus and walked toward a sprawling gray-brick building. As we neared the door Aunt Mary bent down. “Now remember,” she whispered, “don’t ever tell them your daddy died of consumption or they’ll send you away. And try not to cough—ever!”

Then we were in a long corridor and Aunt Mary led me before a table behind which presided a tall woman in black. I stared up at her in awe.

“‘Ere’s Lily Shell,” Aunt Mary said.

The woman fiixed her eyes on me and suddenly I was appaUed. I shrank back but Aunt Mary’s hand held me firmly and before a moment passed, the woman waved us on. Then, unexpectedly, I found myself in a large room with other girls and Aunt Mary was nowhere to be seen.

With the others I did as I was told. I placed my clothes in a pile on the floor. I watched, not understanding and so not ashamed as an older girl gingerly lifted my clothes with a pair of tongs and dropped them into a huge vat of boiling water. Then I was in another room, seated on a hard chair, a sheet about my naked shoulders and someone was running cold clippers through my hair, again and again, until it was cropped down to the skin. I watched my hair fall about me, ash-blondish and very thick. I did not cry then—I don’t know why—but a week or so later when my head was clipped again and I reached up and felt my brisdy, all-but-naked scalp, I wept bitterly.

A girl led me upstairs. I gazed, astonished, at a long room full of little white toilets. I’d never seen shining white toilets and, enchanted, I began to try them, one after another, but a voice called sharply, “Come here, child!” and I was in another enormous room filled with tubs of hot water and the acrid odor of carbolic soap. I was given a hot bath, soaped and scrubbed thoroughly from head to foot and then toweled dry just as vigorously.

Dressed in woolen bloomers, black stockings, and a dark serge dress with sleeves buttoned to the wrist, I lined up with half a dozen other newcomers—all with our heads cropped—and we marched by twos down a stairway into a cement courtyard.

Suddenly Aunt Mary was at my side, staring at my cropped head. I turned in time to see the look of horror fade from her face. She knelt down and kissed me. “Good-by, Lily,” she said. Her blue eyes were bigger than ever and full-sized tears squeezed from them. “Remember, you’re a lucky child to be here. They’ll take proper care of you. Now, mind your manners, you hear!”

I was in The East London Home for Orphans. I was to remain there until I was fourteen.

When I look back on my early years, it’s hard not to think that perhaps they never happened—that I read it all in Dickens or in some penny-dreadful novel of the time. I was born in London’s East End, not far from Limehouse, in a poverty-stricken tenement neighborhood comparable to New York’s Lower East Side. My mother was a cook in an institution. I never knew my father. He died in Berlin of tuberculosis when I was eleven months old. Why he went there, what he was doing there, 1 never learned. My mother told me little about him; and when I was old enough to be curious, she and I were like strangers to each other. To me she was always a small, tired lady who bore the title. Mother. I knew that for other girls this word held a kind of magic, a warmth and tenderness I yearned for but could not feel.

Until I was six, my mother and I boarded in a basement room with a woman who took in washing. There was a bed and sofa in the room. We rented the sofa from her: That was ours; during the day we lived on it; at night we slept on it. In the room there were always high piles of laundry and always the stinging smell of soap mixed with the pungent one of boiled potatoes, upon which it seemed we existed. 1 see myself perched on an empty packing case and Mother taking several spoonfuls of potato soup and then me sharing her spoon, eagerly taking several spoonfuls, each of us dipping chunks of bread into the soup to fill our stomachs.

When my mother was out working, I kept busy. While the washwoman toiled over her board, keeping an eye on me, I played on the floor amid the laundry or crouched on the stonfe steps leading to the street, lost in games I invented with sticks and bits of string.

Out of the vagueness of those first years, the day I was taken to the orphanage emerges sharply. My mother was unable to leave her job and the neighbor I had been taught to call Aunt Mary—”You have no real aunts, LUy, so we’ll make believe she’s your Aunt Mary”—did her that service. My mother kissed me, gave me my doll, Aunt Mary took my hand in hers, and we left.

In the orphanage that night I went to sleep in a huge dimly-lit dormitory. It was high-ceilinged with a cold wooden floor and row upon row of iron cots. In a woolen nightgown I crawled under my blanket. A lady came into the dormitory. She was tall, with eyes the color of rain. She said, “We’re going to turn off the hats now, and you must behave. Now, no talking. Be sure you go to the lavatory. Does everyone know where the lavatory is?”

There was a small chorus of “Yes, mum’s” and the lights went out.

I lay in the darkness feeling the tears well up. I was in a proper bed but I missed my mother. I didn’t want to talk to anyone or have anyone talk to me. I felt strange. I couldn’t express how I felt. Only now I know that it was a sense of coldness and wide space, of belonging to nothing but the bed upon which I lay.

Lying there, I suddenly remembered. Aunt Mary had left me a little bag of toffees. It had not been taken away. I fell asleep sucking them.

The place in which I found myself was no better nor worse than other institutions of that kind in England. During my eight years there I was not cruelly treated: two hundred of us were handled correctly, sternly, and with complete impersonality. We were fed regularly: bread dabbed with margarine, watery cocoa, and stew twice a week, but the portions were small, there were no seconds, and we were always hungry.

We lived by bells. A gong awoke us at 6:30 a.m., another marched us down to breakfast at 7:00, a third sent us to our daily chores at 8:00—scrubbing floors, polishing woodwork, cleaning pots and pans—still another signaled classes, then lunch, then recess, and so throughout the day until a final gong announced lights out.

We knew we were different. Our heads were cropped every two weeks until we were twelve, both as a hygenic measure and to make us identifiable if we ran away. We were Wards of Charity. We were taught love of God, King, and Country and gratitude toward the trustees, those kind, mysterious ladies and gentlemen who took poor children like us off the streets and prepared us for service as domestics, or if we proved very bright, typists and even secretaries. We knew we were not like other children. For we were inside, living behind high walls and locked gates, while they were outside, free to play as they wished, to walk with their mothers and fathers. We watched them day after day from the barred windows of our dormitory. And none of them had cropped heads.

Yet I was puzzled. Didn’t I belong to somebody? I had a mother. If I had a mother, why was I here? I asked Jessie Duchard, a girl who came a year before me. She was snub-nosed and pert, with wide-apart eyes and a carefree disposition. Like me, she had one parent—a father.

“He didn’t want me,” Jessie explained. “He said I was in the way and nobody else wanted me’ so they put me here.” And then, “That’s why they put you here, too. Your mother didn’t want you.”

I could believe that. Once, I faintly remembered overhearing my mother and Aunt Mary. Aunt Mary had said, “It’s a pity she’s so plain.” I had waited, breathless, for my mother’s reply. She had only sighed, heavily.

So it was true. I was plain. And they didn’t want me.

Each time I ventured to look into a mirror only confirmed my plainness. My face was pale as marble. I was thin and scrawny. I had a perpetual cold. My eyes were red, my nose was always running. My ears and neck itched with eczema. I knew I was unattractive; when the trustees came, they never patted me on the head as they went by.

Who would want a girl like me?

If it was Jessie who helped me realize that I was undesirable, she also taught me there were ways to get what you wanted.

On Saturdays during the summer a group of us were taken to a small park and left there to amuse ourselves on the swings or to gorge ourselves with wild berries while our teachers stole a few hours off. One Saturday, as soon as our teachers left, Jessie led me out of the park. I was aghast: this was breaking rules. I followed her nervously down a side street until we came to a movie. On the marquee I spelled out WILLIAM S. HART IN THE GUNFIGHTER. “Do what I do,” Jessie whispered.

We took a stance between the ticket window and the entrance so that anybody going in had to pass us. Each time someone approached the window Jessie began to sigh as though her heart would break. I followed suit. We must have made an odd appearance, identical with our bald heads, our calico pinafores, our faces turned up in eager yearning. Two or three persons passed us before we were rewarded. Then a middle-aged couple, tickets in hand, came by. Jessie looked beseechingly at the woman, then at the ticket window, and heaved a tragic sigh.

The woman melted. “Do you children want to go in and see the picture?”

“Oh yes, madam,” Jessie breathed. “We like William S. Hart ever so.”

I was speechless. My eyes were on the woman’s face, too, and I was literally willing her to take us in. The words ran over and over in my mind: Oh give us the money, give us the money, please give us the money.

The woman opened her purse. “Here’s a penny each.” She smiled down at us. “Now buy your tickets and enjoy yourselves.”

We ran to the window, reached up and plunked down our money, received our tickets and trooped in. It was pure bUss to sit in the darkness, our eyes glued to the screen, while William S. Hart galloped across the plains of far-off America to the stirring music pounded out by the pianist down in front. Then we stared awe-struck at what I now know were modest Uttle comedies played out on the tree-hned streets of Los Angeles. But we thought we saw heaven. We gaped at the story-book homes with their perfect well-kept lawns, at the elegantly dressed children with their ponies, at the unbelievably sumptuous interiors of tlie houses. It seemed such a beautiful, such a warm life where children were free to play without bells ordering them through the day, who had smiling parents who spanked them so lovingly when they were cheeky or disobedient.

We came out into the bright daylight.

“Cor!” said Jessie, somehow expressing in one word all we felt. We sighed. This time we meant it.

The following Saturday we begged our way into the movie again. On the way back to the park we passed a fish-and-chips shop. It had only the lower half of a glass window—painted a checkerboard red and black. Above it, from the interior of the store, there wafted out the most heavenly odors on wings of steam. We watched as men and women emerged carrying their fish and chips in little funnels of paper, eating as they walked.

Jessie and I looked at each other. Without a word we took our places lq front of the checkerboard window, put our heads up and began snifiing hungrily, loudly, and looking appealingly at every passer-by. This paid off, too. “All right, Uttle girls,” a burly man said as he walked past. He tossed us a coin.

We ran inside. Behind a long counter on which were chained large canisters of salt and bottles of vinegar, a man in an apron was busy serving up penny portions of fish and chips. He scooped a dipperful of chips into half a sheet of newspaper, twisted it with a flick of his wrist and presented it to us. Jessie salted our chips, doused them expertly with vinegar, and flushed with victory we floated out and down the street, our cheeks bulging.

I learned quickly now. I began to forage for myself. Other girls were hungry. I was always ravenously hungry. One day, wandering aimlessly down a long corridor in the orphanage, I found myself in a dark room surrounded by huge barrels of cocoa, sugar, and flour. Suddenly I was inspired. Sugar and cocoa, chewed together should be almost as good as a chocolate bar. I began scooping handfuls of sugar and cocoa into my bloomers kept tight above each knee with strong elastic. I was barely able to waddle away.,

In the darkness of the dormitory that night Jessie and I munched sugar and cocoa untO our mouths were too dry to talk. Jessie managed to whisper, “Lily, you are clever. And you wouldn’t think it to look at you.”

But I didn’t need Jessie to tell me that. My mind was quick: I was an excellent student. When a prize of sixpence was offered for memorizing a poem, I did it in two readings. By the time I was twelve I was first in my class. My composition, “Why England Defeated the Hun,” was read aloud to the entire school. To pit myself against others—and win—was enough to keep me glowing for days. Miss Walton, my teacher, watching me throw myself strenuously into every game, every contest, would say, “It’s do or die with you, Lily, isn’t it?” She was right. To be second in anything drove me to tears: I had to win.- I was quick to insult, quick to lash back blindly at anyone who struck me. Once I was actually haled before Miss Mead, the matron, for striking a teacher who had slapped me. I could not explain it. It was pure reflex. Then—and in years to come—at any challenge, I fought back as though fighting for my life.

Eagerly I looked forward to any break in our routine. Once a year, at Christmas, we were taken to the pantomime. Once every three months there were visting days. Sometimes my mother came to see me. She was a stranger, someone whose hands were warm and who kissed me lingeringly. Invariably she brought me a bag of broken biscuits. I bolted them down while she asked me questions. It was always a lame, unsatisfactory meeting. “Have you been all right? No coughing? You’re not mak-mg trouble?” I would nod or shake niiy head, my mouth full, embarrassed by her attention, wanting her to stay, yet wishing she would go now that I had my biscuits.

One visiting day, Jessie came running in great excitement. Her father had unexpectedly appeared, and she wanted me to meet him. I was afraid. She had once told me he hardly ever came because he drank so much he was sleepy all the time. Out of the past a memory haunted me. I saw a large street crowd: I peeped through to see a man on his hands and knees, groaning, floundering in his own filth, and a policeman throwing paUs of water on him to clean him off. Someone said, “That bloody drunk!” My flesh crawled—I fled. But Jessie’s father turned out to be a thin, apologetic little man with a wispy mustache who said only, “Blimey, wot a fine plyce they’ve got you in!” Jessie brimmed over with pride. Now no one could doubt that she really had a father.

But my greatest excitement came with the trustees’ annual visits. For days we were put to work polishing brass, waxing floors, cleaning and scrubbing every corner. Then, upstairs, we would press our noses to the windows, waiting. Presently the enormous black limousines drove up, the chauffeurs ceremoniously opened the doors of the cars, and the trustees stepped out.

Except in movies I had never seen people so elegantly dressed. My heart pounded. What I waited to see—what my eyes yearned to look upon each year—was a little blond girl who descended daintily from a magnificent automobile. She was a trustee’s daughter. The first time I saw her she could have been no older than I—perhaps eight or nine. She was a vision out of a fairy tale. She had long golden curls falling down her back, she was dressed all m white—a white frock, a white coat, and a hat tied in a bow under her chin, white slippers and white gloves —and I stared at her, spellbound. Everything about her burned into my memory. She seemed to glide, not walk, at her father’s side and as she moved I made out just the edge of a fragile pink petticoat. Her skin was pink and white and she looked so cared for, so well tended, even to the white muff into which she put her small gloved hands.

I do not know if the full contrast between us struck me, and how sharply, but I knew how I looked. My hands were rough and red, the knuckles spHt with chilblains, my head was bald, my nose was red from sniffling, my black stockings were bunched and lumpy on my broomstick legs, my shoes were black and clumsy, my bloomers reeked of cocoa— Oh, the trustee’s daughter! How wonderful, I thought, to be a girl like that. It was not envy; you cannot envy what lies hopelessly beyond your reach. I could no more envy her than I could have envied a royal princess. She represented everything the outside world could be. I thought simply, fervently, how nice it would be to be like that.

Was it then that I promised myself, without being aware of it, that someday / would become that girl, live as she lived, and be as she was? I do not know. I only remember how little I thought of myself, how worlds apart I knew we were, when 1 saw that lovely little girl with the golden curls, so well-tended, so pink and white, so beautiful and elegant, the trustee’s daughter.

Next chapter 2

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).