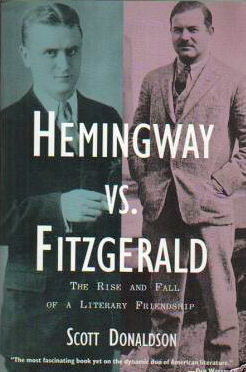

Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship

by Scott Donaldson

Chapter 8

Alcoholic Cases

First the man takes a drink,

Then the drink takes a drink,

Then the drink takes the man.

—Japanese saying

On Comedy Central's August 26, 1998, “Daily Show,” Craig Kilborn reported that Ernest Hemingway's posthumously published True at First Light contained an account of his supposed “marriage,” when on safari in Africa, to a young native girl. This news inspired Kilborn to comment that when Scott Fitzgerald heard about Hemingway's eighteen-year-old African “bride,” he demanded an eighteen-year-old bottle of Scotch.

The punch Une from Kilborn derived from the prevailing public perception of the two famous writers: Hemingway a macho adventurer, Fitzgerald an indoor drunk.

There are alcoholics and alcoholics. Liquor is no respecter of persons, as a visit to any Alcoholics Anonymous meeting quickly reveals. The people who rise to announce, “My name is_____, and I am an alcoholic” are truck drivers and schoolteachers, business executives and door-to-door salesmen, panhandlers and artists, housewives and professional women. What they have in common is the misery that drinking has brought them. The horrific stories they tell run to a pattern. At one stage or another in their lives, they were taken drunk.

Fitzgerald's Case

Fitzgerald became an alcoholic in his late twenties, and for the rest of his lamentably short life never quite shook free of the malady. The story of hisfriendship with Hemingway has been full of talk about his drinking—talk from Ernest, from Max Perkins, from Harold Ober, and above all from Scott himself, as he variously minimized or claimed victory over the demon that possessed him.

By the time Scott and Ernest met in 1925, Fitzgerald's “cafard”—as John Cheever, another alcoholic writer, called it—had taken over control of his being. The most striking thing about Scott's drinking, Ernest thought, was that he got drunk after imbibing so little. It was “hard to accept him as a drunkard, since he was affected by such small quantities of alcohol.” Hemingway converted drinking—like most endeavors—into a competitive sport. In his view, holding one's liquor was a test of manhood—a test that Scott failed at their first meeting and kept failing on serial occasions thereafter. “Fitzgerald was soft,” he told an interviewer in 1960. “He dissolved at the least touch of alcohol.”

Hemingway himself loved to drink and from his earliest years in Europe made it an essential part of each day's activity. He had a vast capacity for the stuff—perhaps owing in some degree to his six-foot, two-hundred-pound frame—but eventually liquor had its debilitating way with him. He was a functioning alcoholic for many years before drink took the man.

There was always a trace of the theatrical in Fitzgerald's drinking. As a boy he sometimes pretended to be drunk, reeling around a streetcar for the entertainment of its passengers. His Ledger recorded his first serious intoxications, “Tight at Susquehana” in April 1913 when still in prep school, “Tight in Trenton” in October 1913 as a Princeton freshman, “Passed out at dinner” celebrating election to the Cottage Club in March 1915. During his college years he often bragged about his drinking. “Pardon me if my hand is shaky,” he wrote a girlfriend, “but I just had a quart of sauterne and 3 Bronxes.” Very probably, he hadn't. His friends at Princeton did not think of him as a lush, and suspected him of playing the clown.

In Zelda Sayre, he found a companion who liked drinking—and exhibitionism—as much as he did. When she broke off their engagement in the summer of 1919, he went on a three-week bender in New York that is vividly described in This Side of Paradise. Once they were married, Scott and Zelda became mutually notorious for their behavior when on a party—leaping fully-clothed into the Pulitzer fountain outside the Plaza Hotel, rolling champagne bottles down Fifth Avenue at dawn. Published in the newspapers, these exploits established them as the prototypical Jazz Age couple, in rebellion against the mores and standards of the older generation. Though he was conservative—even puritanical—about matters of sex, Fitzgerald eagerly accepted the role of the defiant young man. In a letter to a friend back in St. Paul, he repudiated a pallidcareer as a merchant or politician, envisioning himself instead as following in the footsteps of such “drunkards and wasters” as “Shelley, Whitman, Poe, O. Henry, Verlaine, Swinburne, Villon, Shakespeare.”

From the earliest days of their marriage, the Fitzgeralds' outrageous behavior courted trouble. Usually their spontaneity and charm and good looks would win people over, but not always. A month after their marriage and the publication of This Side of Paradise, they went down to Princeton for house party weekend. Scott introduced Zelda as his mistress, acquired a black eye during a scuffle in Harvey Firestone's car, and was summarily suspended from membership in the Cottage Club. Fitzgerald, always sensitive to social slights, was bitterly hurt. In a poem memorializing the occasion, Edmund Wilson (who had accompanied the Fitzgeralds to Princeton) put Scott's sins into perspective:

Poor Fitz went prancing into the Cottage Club

With his gilt wreath and lyre,

Looking like a tarnished Apollo with the two black eyes

That he had got, when far gone in liquor, in some unintelligible fight,

But looking like Apollo all the same, with the sun on his pale yellow hair;

And his classmates who had been roaring around the campus all day

And had had whiskey, but no Swinburne,

Arose as one man and denounced him

And told him that he and his wife had disgraced the club and that he was no longer worthy to belong to it

(Though really they were angry at him

Because he had achieved great success

Without starting in at the bottom in the nut and bolt business).

By 1921, in his twenty-fifth year, Fitzgerald's drinking escapades had developed into something far more damaging than high old times. What had started out as gay irresponsible partying turned destructive. He and Zelda rented a house in Westport, presumably to escape the continual alcoholic haze of New York. But “Fitzgerald vanished into the city on two- and three-day drunks, after which neighbors would find him asleep on the front lawn. At dinner parties, he crawled around under the table, or hacked off his tie with a kitchen knife, or tried to eat soup with a fork.” Once he drove his car into a pond, deliberately. He shocked new acquaintances by introducing himself as “F. Scott Fitzgerald, the well-known alcoholic.” His behavior became increasingly unfunny. As he confessed in a letter, he “couldn't get sober long enough to tolerate being sober.”

Fitzgerald in his cups became alternately belligerent and maudlin. He and Zelda began to quarrel, in large part because of her flirtatiousness and his fear of what might happen when she was intoxicated. In May 1921 they again attempted to quiet the hectic pace with a geographical change—this time, a trip to Europe. Shortly before leaving, Zelda goaded him into a brawl, in which Scott—at a mere five feet seven and 140 pounds—was clobbered by a professional bouncer.

The European trip did not change their style of life. On return they went to St. Paul to await the birth of their only child, Scottie, where Fitzgerald wrote Perkins a discouraged letter lamenting five months of loafing. The Beautiful and Damned was in press, but Scott commented that his next novel, “if I ever write another, will I am sure be black as death with gloom.” He would like to sit down with half a dozen chosen companions and drink himself to death, he added. If it weren't for Zelda, he would disappear for a few years: “[s]hip as a sailor or something and get hard.”

The public reputation he was constructing as a rebellious Jazz Age playboy stood at odds with the image he was hoping to establish of a serious and dedicated writer. It did not help when his friend Thomas Boyd reported in the St. Paul Daily News that Fitzgerald “had been sequestered in a New York apartment with $10,000 sunk in liquor and that he was bent on drinking it before he did anything else.” Luckily Edmund Wilson sent Scott a pre-publication draft of the extended article he was writing on him for the January 1922 Bookman. There were a number of slurs in that rather patronizing piece that Scott might have objected to, but the only thing he asked Wilson to change was the emphasis on drinking.

“Now as to the liquor thing—,” he wrote Wilson, “it's true, but nevertheless I'm going to ask you to take it out… the legend about my liquoring is terribly widespread and this thing would hurt me more than you could imagine—both in my contact with the people with whom I'm thrown—relatives and respectable people [especially Zelda's parents, who “never miss The Bookman”]—and, what is much more important, financially.” Wilson cut most of his copy on Fitzgerald's drinking.

In their restless careering about, Scott and Zelda next fetched up in Great Neck, Long Island. Fitzgerald's play The Vegetable went into production, and they saw a lot of the theatrical crowd and of Ring Lardner, with whom Scott consumed “oceans of Canadian ale.” In his Ledger for July 1923, Fitzgerald recorded the pattern of his days: “Intermittent work on novel. Constant drinking.” After the failure of his play, and a fallow period in his writing, Fitzgerald wrote Perkins that he realized how much he'd “deteriorated” in the previous three years, spending time “uselessly, neither in study nor in contemplation but only in drinkingand raising hell generally.” Still, he felt he had “an enormous power” in him, and proved it by writing his masterful The Great Gatsby in 1924.

With that task behind him, Scott's trouble with the bottle began again. In Rome, he was beaten by the police after a drunken argument—an incident he wove into Dick Diver's downfall in Tender Is the Night. He and Zelda “sometimes indulge[d] in terrible four-day rows that always start with a drinking party,” he wrote John Bishop early in 1925. When he met Hemingway at the Dingo in Paris and ignominiously passed out, the probability is that Fitzgerald was in the midst of a drinking cycle lasting for several days.

In his Moveable Feast account of their trip to Lyon, Hemingway carefully distinguished his own drinking habits from those of Fitzgerald. “In Europe then,” he explained, “we thought of wine as something as healthy and normal as food and also as a great giver of happiness and well being and delight.” He took wine or beer with his meals as a pleasant and perfectly natural part of everyday life. For Fitzgerald, on the other hand, the consumption of liquor only served to make him drunk. In his judgment, Scott simply couldn't handle booze. Yet on the day of their driving trip, as Hemingway recalled it, the two of them consumed five bottles of Macon in the car. As the expert in these matters, Ernest uncorked the bottles as needed and passed them to Scott. Drinking from the bottle “was exciting to him as though he were slumming or as a girl might be excited by going swimming for the first time without a bathing suit.”

By early afternoon Fitzgerald became convinced that he was suffering from congestion of the lungs and they stopped for the night at a hotel. There they drank three double whiskey sours apiece before going down to dinner. Scott told Ernest about Zelda's affair with the aviator Edouard Jozan at St. Raphael so clearly that Hemingway “could see the single seater seaplane buzzing the diving raft and the color of the sea and the shape of the pontoons and the shadow that they cast and Zelda's tan and Scott's tan and the dark blonde and the light blond of their hair and the darkly tanned face of the boy that was in love with Zelda.” Ernest drank most of a carafe of Fleurie while Scott was on the telephone with Zelda, and when he came back to the table they ordered a bottle of Montagny, “a light, pleasant white wine of the neighborhood,” with their dinner. Scott ate very little, and passed out after sipping at one glass of the wine.

Considering the amount of alcohol he had imbibed that day and evening, this was not surprising. But it surprised Hemingway. He decided that anything Scott drank would first over-stimulate him and then poison him, and he resolved to cut all drinking to the minimum the following day. He would tell Scott that he, Ernest,could not drink because they were getting back to Paris and he “had to train in order to write.” This was not true, for Hemingway's sole rules on the subject were “never to drink after dinner nor before [he] wrote nor while [he] was writing.” But it would keep Fitzgerald from the liquor that acted on him like a poison.

During the months ahead, Ernest and Hadley were to discover just how much of a nuisance Fitzgerald could be when he was on a party. “The six o'clock in the morning drunk,” Hadley called him. He and Zelda would turn up at the Hemingways' apartment at outlandish hours, and do foolish things like unraveling a roll of toilet paper from the top of their stair landing. At first Ernest let them in when they came to call. He found it interesting, Hadley thought, to watch an alcoholic demean himself. Later, when the Fitzgeralds' disturbances threatened to get them kicked out their apartment, Hemingway became increasingly intolerant of their drunken misbehavior. Hadley shared her husband's impression that Scott simply couldn't handle liquor. He “would take one drink and pretty soon he'd turn pale green and pass out.” But hadn't he and Zelda been consuming alcohol all night before they paid their early-morning call on the Hemingways and took that “one drink”?

By the mid-1920s, liquor was beginning to determine the course of Scott Fitzgerald's life. Excessive drinking was ruining his marriage and affecting his ability to work. The talent was extant, but his dedication to the task dwindled steadily under the influence of the bottle. And worst of all, for someone who lived for the approval of other people, Fitzgerald's outrageous behavior when intoxicated was alienating those he most cared about—including Ernest Hemingway and Gerald and Sara Murphy.

The etiology of alcoholism is a notoriously complicated subject. It is a disease traceable to hereditary factors, some maintain: in Fitzgerald's case that makes some sense, for his father had a drinking problem. Chemistry causes the malady, others hold. In this connection, a number of biographers (and one psychiatrist) have attributed Fitzgerald's troubles to hypoglycemia, a condition in which the body produces an excess of insulin and a craving for sugar that alcohol can supply. But the most authoritative and knowledgeable biographer, Matthew J. Bruccoli, concluded that there was no medical evidence to support such a diagnosis. According to Dr. William Ober, a pathologist who examined Fitzgerald's medical records, “[h]e did not drink because his blood sugar level was low; he drank because he was a drunkard. 'Drunkard' is the old-fashioned term for alcoholic, and, as we know today, it is an addiction, a form of escape for people with inadequate personalities, people with deep-seated insecurities, people with unresolved intra-psychic conflicts (often sexual but by no means always so), as well as people… who use it to drown out the still small voice of self-reproach.”

Dr. Ober's reasoning nicely fits the case of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who was handicapped by social insecurity and drank in order to cover it up. John Dos Passos, a firsthand observer of Fitzgerald's antics at Antibes in the mid-1920s, speculated that he was not always as intoxicated as he seemed to be, and that he put on his drunk and disorderly performance “because he had never learned to practice the first principles of civilized behavior.” Lacking any sure sense of himself, he played two roles: Prince Charming and Peck's Bad Boy. Fitzgerald could be “quite irresistible” when he set out to charm, and quite impossible when he switched into his naughty boy routine. His mother had forgiven him all such misbehavior. His contemporaries, even the long-suffering Murphys, were less tolerant.

During the summer of 1926, Fitzgerald went out of his way to antagonize Gerald and Sara. He ruined their party for Hemingway by throwing ashtrays and crawling around like a dog. During another party at the Murphys' elegant Villa America, he threw a fig at a titled female guest, smashed the Venetian glassware, and punched both Gerald and Archie MacLeish. While Scott was rade beyond imagining, Zelda liked to take risks. She threw herself down a flight of stone steps one night when Scott paid undue attention to the dancer Isadora Duncan. She insisted on making dangerous dives from the cliffs, and dared Scott into following her lead. In their car, on the winding roads above the Mediterranean, they were a menace to themselves and everyone on the road. The Murphys were exceptionally fond of the Fitzgeralds, and exceptionally understanding. But their patience was not infinite, and on occasion they exiled Scott and Zelda from their circle for specified periods of time.

The Fitzgeralds sailed back to the States in December 1926, alighting at Ellerslie mansion outside Wilmington. In the year-end summary of his Ledger, Scott excoriated himself. “Futile, shameful useless… Self-disgust. Health gone.”

In his journals or in correpondence, Fitzgerald took himself to task for his drinking. In public pronouncements, he was much less willing to do so. Writing Hemingway in September 1929, for example, he characterized his “drinking manners” as worse than those of the lowest bistro boy. But he adopted a far more light-hearted approach in “A Short Autobiography,” a piece he wrote for the New Yorker that year. The “autobiography” takes the form of an annual diary. Listed under each year were the particular alcoholic beverages he remembered drinking, and where. The first and last entries were:

1913

The four defiant Canadian Club whiskeys at the Susquehanna in Hackensack.

1929

A feeling that all liquor has been drunk and all it can do for one has been experienced, and yet—“Garçon, un Chablis-Mouton 1902, et pour commencer, une petite carafe de vin rose. C'est ça—merci.”

He could not treat his drinking so cavalierly after Zelda collapsed in the spring of 1930. One after another of the doctors who treated her urged Scott to give up alcohol in order to facilitate her recovery. Fitzgerald's letters to these doctors provided a remarkable record of the rationalization and denial symptomatic among alcoholics.

Summer 1930, to Dr. Oscar Forel (italics Fitzgerald's):

“My work is done on coffee, coffee and more coffee, never on alcohol.”

“It was on our coming to Europe in 1924 and upon her urging that I began to look forward to wine at dinner—she took it at lunch, I did not… The ballet idea was something I inaugurated in 1927 to stop her idle drinking after she had already so lost herself in it as to make suicidal attempts.”

“Two years ago in America I noticed that when we stopped all drinking for three weeks or so, which happened many times, I immediately had dark circles under my eyes, was listless and disinclined to work… I found that a moderate amount of wine, a pint at each meal made all the difference in how I felt.”

“Wine was almost a necessity to me to be able to stand her long monologues about ballet steps, alternating with a glazed eye toward any civilized conversation whatsoever.”

“To stop drinking entirely for six months and see what happens, even to continue the experiment thereafter if successful—only a pig would refuse to do that. Give up strong drink permanently I will. Bind myself to forswear wine forever I cannot... the fact that I have abused liquor is something to be paid for with suffering and death perhaps but not with renunciation… I cannot consider one pint of wine at the day's end as anything but one of the rights of man.”

“Is there not a certain disingenuousness in her wanting me to give up all alcohol? Would not that justify her conduct completely to herself and prove to her relatives, and our friends that it was my drinking that had caused this calamity, and that I thereby admitted it?”

To sum up Fitzgerald's points, the problem was Zelda's, not his. She started him drinking in the first place, and later became so boring about the ballet that he had to continue. He did not drink when he was working. Not drinking was bad for his health. He would give up hard liquor, but not the wine he deserved at the end of the day. If he had abused liquor in the past, he'd suffered enough for it. And if he stopped drinking, wouldn't that make him the villain of the piece?

March 1932, to Dr. Mildred Squires:

“…if the situation continues to shape itself as one in which only one of us two can survive, perhaps you would be doing a kindness to us both by recommending a separation.”

“Perhaps fifty percent of our friends and relatives would tell you in all honest conviction that my drinking drove Zelda insane— the other half would assure you that her insanity drove me to drink. Neither judgment would mean anything. The former class would be composed of those who had seen me unpleasantly drunk and the latter of those who had seen Zelda unpleasantly pyschotic. These two classes would be equally unanimous in saying that each of us would be well rid of the other—in full face of the irony that we have never been so desperately in love with each other in our lives. Liquor on my mouth is sweet to her; I cherish her most extravagant hallucination.”

In the context of suggesting that it might be better if he and Zelda separated, Scott acknowledged his weakness for drink as complementary to her schizophrenia. They were terribly dependent on each other's illness.

Spring 1932, to Dr. Mildred Squires (after Zelda finished Save Me the Waltz and sent it to Max Perkins):

“You will see that same blind unfairness in the novel. The girl's love affair is an idyll—the man's is sordid—the girl's drinking is glossed over (when I think of the two dozen doctors called in to give her 1/5 grain of morphine on a raging morning!), while the man's is accentuated.”

According to Scott, Zelda was the really serious abuser of alcohol in the family.

Spring 1933, to Dr. Adolf Meyer:

“When you qualify or disqualify my judgment on the case, or put it on a level very little above hers on the grounds that I have frequently abused liquor I can only think of Lincoln's remark about a greater man and heavier drinker than I have ever been—that he wished he knew what sort of liquor Grant drank so he could send a barrel to all his other generals.

“This is not said in any childish or churlish spirit of defying you on your opinions on alcohol—during the last six days I have drunk altogether slightly less than a quart and a half of weak gin, at wide intervals. But if there is no essential difference between an overextended, imaginative, functioning man using alcohol as a stimulus or a temporary aisment and a schizophrène I am naturally alarmed about my ability to collaborate in this cure at all.”

“The witness is weary of strong drink and until very recently he had the matter well in hand for four years and has it in hand at the moment, and needs no help on the matter being normally frightened by the purely physical consequences of it. He does work and is not to be confused with the local Hunt-Club-Alcoholic and asks that his testimony be considered as of prior validity to any other.”

“I can conceive of giving up all liquor but only under conditions that seem improbable—Zelda suddenly a helpmate or even divorced and insane. Or, if one can think of some way of doing it, Zelda marrying some man of some caliber who would take care of her, really take care of her.”

In summary, Fitzgerald protested that Dr. Meyer should trust his judgment and not Zelda's. He used liquor as a stimulus for his work and/or to ease the pressures of the day, but was no ordinary hunt-club drunk. He could even imagine quitting entirely, but only if the real problem, embodied in Zelda and her illness, were removed. As with Dr. Squires a year earlier, Fitzgerald sounded as if he would welcome such a resolution, no matter how it was achieved.

May 1933, Zelda and Scott in discussion with Dr. Thomas R. Rennie:

Scott: “I am perfectly determined that I am going to take three or four drinks a day.” If he stopped, he told Dr. Rennie, “[Zelda's] family and herself would always think that that was an acknowledgment that I was responsible for her insanity.”

Zelda, asked by Scott what caused him to think he had ruined his life (he meant her mental illness): “I think the cause of it is your drinking. That is what I think is the cause of it.”

The issue joined between them, with Scott maintaining the high ground because of his so-far less debilitating disease.

The Fictional Evidence

A reader of Fitzgerald's fiction who knew nothing at all about his life might logically conclude that the author was a habitual drinker. Why else would he bring up the subject so often and create so many alcoholic characters? The tendency was apparent from the beginning. In This Side of Paradise, Fitzgerald's autobiographical protagonist goes on an extended bender like the one Scott himself underwent after rejection by Zelda. Still more striking was the portrayal of Anthony Patch's alcoholic ruin in The Beautiful and Damned. Anthony's descent into alcoholism is conveyed with convincing authenticity. Near the end of the novel, he gets into a fight with his wife Gloria and stalks out of their apartment. “He's just drunk,” Gloria tells an observer, who cannot believe it—he had seemed absolutely sober. But that's the terrible mundane way of it, Gloria explains. “[H]e doesn't show it any more unless he can hardly stand up, and he talks all right until he gets excited. He talks much better than he does when he's sober. But he's been sitting here all day drinking.”

In The Great Gatsby, Gatsby himself is never drunk and the narrator Nick Carraway rarely so, but the book is saturated with liquor. In this novel, drinking can lead to hilarious consequences, as when an inebriated guest tries to drive a car shorn of one of its wheels. “No harm in trying,” he mumbles. Or it can alter perceptions, as happens to Nick during the late-night party at Muriel's apartment in New York. Or it will lighten the atmosphere, as when a tray of cocktails floats into view. The entire novel is structured around a series of parties, in a faithful recollection of the Fitzgeralds' days on Long Island. But in Nick's view and that of the author who stands behind him, the pervasive drinking of the characters causes nothing important to happen. The tinkling of glasses simply functions as background.

As his own condition worsened, Fitzgerald increasingly turned to alcoholics and their troubles for the subject matter of his stories and novels. Zelda'scollapse and the doctors who challenged him to help her (and himself) by giving up drinking were obviously reflected in two stories of 1931, “Babylon Revisited” and “A New Leaf.” Charlie Wales, the protagonist of “Babylon Revisited,” looks back on the boom years of too much drinking. One wintry night, when his wife was flirting with another man and he was drunk, he locked her out of their Paris apartment—and she contracted pneumonia and died. Now he has stopped drinking, except for one invariable drink every day, and wants to lead a healthy and responsible life. Yet there remains some question whether Wales has really reformed. On the one hand, he has come to understand the meaning of the word “dissipate”—to make nothing out of something. Yet at the same time he returns compulsively to the places where he indulged in that dissipation. On the one hand, he believes in character and wants to jump back a whole generation “and trust in character again.” On the other hand, he is inclined to parcel out his guilt for the tragic death of his wife to the general debauchery of the times or simply bad luck. In depicting a likable and yet highly suspect reformed alcoholic, Fitzgerald may have been expressing some of his own ambivalence on the subject. Or confessing that in his periods of drunkenness he had in effect locked Zelda out in the cold.

In the person of Dick Ragland in “A New Leaf,” he painted his most convincing portrait of a man destroying himself through drink. The story is narrated by Julia, and the reader is asked to share both her initial enchantment with Dick and her subsequent visceral distaste for him. Authentically enough, alcohol produces in him a Jekyll to Hyde transformation. In his charming Dr. Jekyll role, Ragland “was a fine figure of a man, in coloring both tan and blond, with a peculiar luminosity to his face. His voice was quietly intense; it seemed always to tremble a little with a sort of gay despair; they way he looked at Julia made her feel attractive.” He is also honest and forthcoming about what led to his troubles, and here Fitzgerald patently seems to be speaking through his created character. “I found that with a few drinks I got expansive and somehow had the ability to please people, and the idea turned my head. Then I began to take a whole lot of drinks to keep going and have everybody think I was wonderful.”

Julia falls in love with this version of Dick, and is ready to marry him despite his reputation as a drunk. But at another meeting it is Mr. Hyde who appears. “His face was dead white and erratically shaven, his soft hat was crushed bunlike on his head, his shirt collar was dirty, and all except the band of his tie was out of sight… His whole face was one long prolonged sneer—the lids held with difficulty from covering the fixed eyes, the drooping mouth drawn up over the upper teeth, the chin wabbling like a made-over chin in which the paraffin had run—it was a face that both expressed and inspired disgust.”

In those two descriptions, Fitzgerald vividly demonstrated the drastic effects of alcoholism. It is impossible to believe that in observing his own decline he did not share a measure of Dick Ragland's self-disgust.

1932 was not, for Fitzgerald, an auspicious year. “Drinking increased. Things go not so well,” he wrote in his Ledger for September. But he was not fully prepared to condemn drunks in his fiction. Both Dr. Forrest Janney (in “Family in the Wind”) and Joel Coles (in “Crazy Sunday”) emerge as basically sympathetic figures. They may be alcoholics (Dr. Janney assuredly is), but Fitzgerald asks us to like them.

The situation with Dick Diver was much the same. Especially in the opening section, Tender built Diver up as immensely charming. When he later suffers his downfall, we are apt to ascribe it to factors other than his drinking— the influence of too much Warren money, for example. Fitzgerald shows the drinking and its effects, as on the night in Rome when the drunken Dr. Diver brawls with the police and spends the night in jail. Fitzgerald did not want to deprive his hero of all dignity, however, and carefully revised the final scene of the novel to make his hero less obviously intoxicated. In its final two drafts, the novel ended with Diver drunk. In one version, he falls on his face; in another, he is helped away by a waiter Baby Warren sends to assist him. In the published book, Diver drinks enough to be “already well in advance of the day,” and sways a little as he stands up to bless the beach, but requires no assistance in keeping his feet.

Tender was unusual in dividing its alcoholism between Dick Diver, a primarily admirable figure, and poor Abe North, who is assigned the cruder attributes of the drunkard and killed off in absentia. “To give a full, convincing picture of Diver's alcoholism,” Thomas Gilmore has proposed, “might have been as intolerably painful to Fitzgerald as fully accepting his own.”

More or less desperate for material, Fitzgerald drew on his own drying-out periods in undistinguished stories like “Her Last Case” (November 1934) and “An Alcoholic Case” (1937). And during his last two years, he turned out a number of stories about Pat Hobby, a Hollywood hack writer. Hobby has so many things wrong with him, including womanizing and perpetual lying, that the fact that he is a lush is often obscured. “Pat Hobby's College Days,” however, comments indirectly on Fitzgerald's own drinking. In the story, Pat attempts to sell an idea for a college movie to a committee from the University of theWestern Coast. He prepares himself with a slug from the half-pint bottle he invariably carries. But Hobby's sales pitch is ruined when his secretary is ushered into the room with “a big clinking pillow cover” containing empty whiskey bottles. Shortly before writing this story, Fitzgerald had disastrously drunk himself out of a film job at the Dartmouth Winter Carnival. And in fact he assigned his Hollywood secretary the task of disposing of his empties.

***

In correspondence, Fitzgerald often admitted his drinking problem while attributing it to causes beyond his control. Two letters of late 1934 illustrate the pattern. His Ledger for June of that year revealed for the first time that he had suffered episodes of delirium tremens, an acute and sometimes fatal descent into disorientation and hallucination, and that he required a trained nurse to look after him. No word of this was conveyed to Maxwell Perkins or Harold Ober—his two most important and valuable professional supporters—in communications mailed that November and December. Fitzgerald brought up the subject of his drinking with Perkins only to rationalize it away. “I know you have the sense that I have loafed lately but that is absolutely not so. I have drunk too much and that is certainly slowing me up. On the other hand, without drink I do not know whether I could have survived this time.” Fitzgerald also pleaded extenuating circumstances to Ober, who unlike Perkins had reproached him about drinking. “[T]he assumption that all my troubles are due to drink is a little too easy,” he wrote. His domestic difficulties—Zelda's illness—were also to be considered, and the ebbing away of his literary reputation, and the pleurisy he'd come down with on a trip to Bermuda. In previous years he may have been guilty of self-indulgence. Lately the gods had simply not smiled on him.

Throughout his career Fitzgerald supplied his editor and agent with intermittent and seemingly sincere bulletins about quitting. The basic message was that he could stop drinking any time, or even better, that he had gone on the wagon—for six weeks, for three months if you didn't count Christmas, for February and March of 1933. In May 1935 he went so far as to tell Arnold Gingrich of Esquire that he thought his prose looked “rather watery” and he planned to “quit drinking for a few years.” The very fact that he kept making these reassurances was the best reason not to believe them, and it is doubtful if Fitzgerald's periodic announcements of sobriety persuaded anyone—least of all himself. In his notebooks, he rather cynically observed that when “anyone announces to you how little they drink, you can be sure it's a regime they've just started.” And one that would not last.

The notebooks, in fact, contain Fitzgerald's most candid and confessional observations about alcohol and its effects on him. “Drunk at 20, wrecked at 30, dead at 40. Drunk at 21, human at 31, mellow at 41, dead at 51,” one entry reads. If he'd taken his first drink at thirty-five instead, he commented in a 1937 letter, he might have progressed “to a champagne-pink three score and ten.” During his last years, he carried around a portfolio of photographs showing the grisly effects of alcohol on various human organs. “Drinking is slow death,” he warned Robert Benchley. “Who's in a hurry?” Benchley responded.

This was witty, but Fitzgerald had passed the point where drunkenness seemed amusing. Another note conveyed his awareness that misbehavior when intoxicated was destroying him socially. “Just when somebody's taken him up and is making a big fuss over him he pours the soup down his hostess's back, kisses the serving maid and passes out in the dog kennel. But he's done it too often. He's run through about everybody, and there's no one left.” He could apologize all day long, but when there were too many apologies on too many mornings-after, the people he'd offended stopped listening.

Somewhere during the mid-1930s Fitzgerald become convinced that he needed to drink in order to write. He had not believed that at the start. In a 1922 interview with Tom Boyd, he expressed his conviction that liquor was “deadening to work.” He could understand drinking coffee for the stimulation, but not whiskey. By March 1935, this position had been modified. In a letter to Perkins, Fitzgerald asserted that “a short story can be written on a bottle, but for a novel you need the mental speed that enables you to keep the whole pattern in your head and ruthlessly sacrifice the sideshows as Ernest did in 'A Farewell to Arms.'” Organizing a long book or revising it with “the finest perceptions and judgment” did not “go well with liquor.” He would give anything if he “hadn't had to write Part III of 'Tender Is the Night' entirely on stimulant” and could have one more crack at the novel “cold sober.” “Even Ernest,” he added, had commented about sections that were needlessly included, “and as an artist he is as near as I know for a final reference.” In a postscript, Scott maintained that he hadn't had a drink for six weeks and hadn't felt “the slightest temptation as yet.”

Basically Scott was making three points about drinking and the creative process in this letter. The most obvious one was that you could not afford to let alcohol shut down the rational left side of the brain when working on a long book. At the same time, he now believed that short stories could be written whendrinking and that liquor could serve as a stimulant rather than a depressant. Putting those propositions together, he arrived at the conviction that drinking was necessary to his work, or at least to the short fiction by which he earned his livelihood. “Drink heightens feelings,” he told Laura Guthrie in Asheville that summer. “When I drink, it heightens my emotions and I put it in a story… My stories written when sober are stupid… all reasoned out, not felt.” It was a conviction he held until the end of his life. In 1940 he convinced Frances Kroll that for him alcohol was a stimulant, and that he required “the medicinal lift” it gave him.

Once he'd arrived at that rationalization, Fitzgerald was in thrall to drink. James Thurber, another writer afflicted by alcohol, detected the self-justifying process that provided Fitzgerald with multiple reasons for drinking. “Zelda's tragedy, his constant financial worries, his conviction that he was a failure, his disillusionment about the Kingdom of the Very Rich, and his sorrow over the swift passing of youth and romantic love.” All those reasons put together, Thurber believed, were not as harmful to Fitzgerald as the conviction that “his creative vitality demanded stimulation” from liquor. He had to drink in order to write. He had to write in order to live. He would not live long if he continued to drink.

One evening in May 1978, sitting in a bar appropriately enough called “Gatsby's” in Georgetown, I got to talking with Scottie Fitzgerald about her father's drinking. She proposed a two-question test to determine an alcoholic. Did liquor have a drastically unhealthy effect on one's life? Did one's personality change as a result of drinking? In the case of F. Scott Fitzgerald, she'd decided that the answer to both questions was yes. When sober he was a thoughtful and gentle and kind, if somewhat over-solicitous, father. When drunk, he became “a totally different person… not just gay or tiddly, but mean.”

Scottie had reason to know. He embarrassed her dreadfully at the December 1936 tea dance in Baltimore that father and daughter planned together. In the preparatory stages, Fitzgerald was humorous and helpful, but he drank too much at the dance and insisted on weaving around the dance floor with some of Scottie's young friends. She resolutely ignored his gaffe and refused all offers of sympathy from her peers. It could have been worse, she knew. Her father could have become angry or combative. Once he had slapped her for interrupting his writing. Another time he threw an inkwell past her ear.

During his Hollywood years, Fitzgerald's worst behavior emerged in connection with the women in his life—Scottie somewhat, Zelda and Sheilah Graham to a far greater degree.

Scott twice accompanied Zelda on holidays approved by her doctors at Highland hospital, in April 1938 and April 1939. Each outing ended disastrously. In 1938, according to the account Fitzgerald sent her doctors, he “added to the general confusion [of their visit to Virginia Beach] by getting drunk, whereupon she adopted the course of telling all and sundry that I was a dangerous man and needed to be carefuly watched.” She convinced everyone on the corridor of their hotel that he was a madman, and turned the trip into “one of the most annoying and aggravating experiences” of his life. He sobered up the second he put Zelda on the train back to Carolina, Scott maintained.

Zelda's spring holiday the following year provided further evidence that the chemistry between them had turned toxic. For whatever reasons—he too was on holiday, not working, and must have felt at least a modicum of guilt for conducting a long-term affair with Sheilah in Hollywood—Fitzgerald went on a bender whenever he saw his wife. This time they journeyed to Cuba, where Scott was beaten up while trying to stop a cockfight, and to New York, where he ended up in the hospital for detoxification. Zelda went back to Asheville alone, and covered for him with her doctors. For that enabling kindness, he was truly grateful. “You are the finest, loveliest, tenderest, most beautiful person I have ever known,” he wrote her a few weeks later. They never saw each other again.

Scott met Sheilah Graham within two weeks of his arrival in Hollywood in July 1937. A month later they had become lovers, and remained intimate companions for the last three and a half years of his life. For much of that time Fitzgerald was on his best behavior. He knew that his reputation as a drinker preceded him, and managed to stay sober for extended periods. But his demon would only stay stoppered up for so long before pouring out in terrible binges. By this time, the personality change that alcohol produced in him had become spectacular—and the blonde and beautiful Sheilah became its victim.

In her memoir Beloved Infidel, Graham vividly portrayed both sides of the Fitzgerald she came to know. The man she fell in love with was engaging and gallant, sending notes of endearment and standing up for her against the real and fancied detractors she attracted in her role as gossip columnist. Sheilah was a kind of female Gatsby, who changed her name and reconstructed her past on the way toward achieving a successful independent life. She had grown up in a working-class British family, and her education ended in a London school for orphans. As a remedy, Scott devised a “College of One” wherein he set lessons in literature and history and quizzed her on what she had learned. He was the amiable and loving professor, she his eager student. It was an idyll of sorts.

Then there was Fitzgerald drunk. He demanded to know how many menGraham had slept with—as Dick Diver in Tender Is the Night demanded of the actress Rosemary Hoyt. She didn't know what to say. She was twenty-eight, she'd been on the stage in England. Finally she came up with eight as a “nice round figure.” Fitzgerald was shocked, and intrigued, and then overcome with jealousy. He called her his “paramour” in public, he called her a slut in private, on the back of her framed picture he scrawled “Portrait of a Prostitute.” This alcoholic Fitzgerald also became physically dangerous, threatening her and then himself with his pistol. Gingrich met Sheilah in Chicago where she was recording a nationwide radio show on the movies. Scott, on one of his binges, accompanied her and challenged the executive in charge to a fight. Sheilah drew Scott aside, whereupon he abusively turned upon her. “The son of a bitch bit my finger” were the first words Gingrich heard her utter.

Probably the most ruinous drinking bout of Fitzgerald's life came in July 1939, when he broke down on the job at the Dartmouth Winter Carnival. He did irreparable damage to his career on that occasion by presenting himself in a soddenly incoherent state to producer Walter Wanger. Assisted by Sheilah Graham and Budd Schulberg, Scott once again landed at Doctors Hospital in New York for a three-day drying-out period. Ober got wind of the incident, decided to stop advancing Fitzgerald funds, and wrote him a letter explaining why. In a fit of pique, Scott replied that he had indeed “lived dangerously” and might very well have to pay for it, “but there are plenty of other people to tell me that and it doesn't seem as if it should be you.” Back in Hollywood, few producers were inclined to take a chance on someone as unreliable as Fitzgerald. He feared that there was an unofficial blacklist against him, he wrote agent Leland Hayward in January 1940. There were only three days while he was on salary in motion pictures when he “ever touched a drop,” he insisted. “One of those was in New York and two were on Sundays.” Although this was untrue, Fitzgerald did manage to scale back his drinking in the last year of his life.

One precipitating factor was a climactic blowup with Sheilah in October 1939. In the aftermath, Scott wrote an abject letter appealing to her maternal instincts. “I want to die, Sheilah, and in my own way. I used to have my daughter and my poor lost Zelda. Now for over two years your image is everywhere. Let me remember you up to the end which is very close. You are the finest. You are something all by yourself. You are too much something for a tubercular neurotic who can only be jealous and mean and perverse.” Acknowledging some of his ills—the ones that might elicit sympathy—Fitzgerald could not bring himself to declare his alcoholism. Sheilah took him back, but could not persuade him to join Alcoholics Anonymous. He wasn't a joiner, he told her. Besides, “AA can only help weak people… The group offers them the strength they lack on their own.”

By way of demonstrating his own strength, he continued to work steadily on The Last Tycoon even after Collier's rejected a proposal to serialize the novel. He did not stop drinking entirely. Frances Kroll disposed of the bottles he did not want anyone else, Sheilah included, to see. It seemed to Frances that drinking “was not important” to Fitzgerald when he had a major project, like the writing of The Last Tycoon, to complete.

Did Fitzgerald's drinking kill him? As a single cause, probably not. But liquor certainly undermined his health, just as it undermined his career and his relationships. And it was undoubtedly a contributing factor to the heart attack that struck him down in Sheilah Graham's ground-floor apartment on Saturday afternoon, December 21,1940. He was forty-four years old. Dorothy Parker, who came to view his body at the mortuary, looked down at his unlined face and terribly wrinkled hands and gave him a much-quoted send-off. “The poor son of a bitch,” she said. In his notebooks, Fitzgerald wrote an epitaph of his own: “Then I was drunk for many years, and then I died.”

Hemingway's Case

Hemingway was a late-blooming alcoholic, and did not regularly make the public displays of himself that characterized Fitzgerald's histrionic drunkenness. As a result, we know much less about his drinking than about Scott's. Still, Hemingway's letters and his fiction, and the testimony of his friends and doctors, make it possible to trace the course of his drinking life.

Still more than for Fitzgerald, Hemingway regarded drinking as an act of rebellion against conventional mores. He was brought up in a teetotalling household, and in a suburban community which prided itself on maintaining old-fashioned values. It was not surprising that he—and his fictional counterparts—went out of their way to defy convention. In his first letter back home after his wounding in Italy, written on his nineteenth birthday, Ernest adopted an aggressively upbeat tone. He was in a peach of a hospital, there were about eighteeen nurses for four patients, the surgeon was one of the best in Milan, he hoped to be back driving in the mountains by August. In short, there was nothing for his parents to worry about, or at least nothing associated with his injury. At the end of his letter, Ernest appended a stick figure drawing of himself, lying prone with 227 wounds in his legs. Issuing from his mouth was a cartoon balloon, reading “gimme a drink!” That phrase, which must have shocked his parents, declared his independence from them on the subject of drinking. He was letting them know that in Italy, serving as a volunteer in the war, he had learned—and earned the right—to drink.

In fact Hemingway drank so much in the hospital, enlisting nurses and orderlies as his agents to secure his supply of liquor, that he got into trouble with the head nurse. The episode is re-created in fictional form in A Farewell to Arms, where the obtuse and straitlaced Miss Van Campen discovers Frederic Henry's cache of brandy bottles and accuses him of drinking in order to induce jaundice and so delay his return to the front. Even Agnes von Kurowsky, the nurse he'd fallen in love with, warned Ernest, good-naturedly enough, not to “lap up all the fluids at the [G]alleria” when she was transferred away from Milan.

From the beginning, Ernest had a prodigious capacity for alcohol. In correspondence with fishing buddies from Walloon Lake and friends from the ambulance corps, he repeatedly boasted about his intake. “Lately I've been hitting it up,” he wrote Bill Smith in December 1918, “about 18 martinis a day.” Back in the States six months later, he told Howell Jenkins that he'd established “the club record” in a drinking bout in Toledo: “15 martinis, 3 champagne highballs, and I don't know how much champagne then I passed out.” Hemingway converted drinking like almost everything else into a competitive sport, and valued companions who could compete with him in their consumption of alcohol. Drinking together established a kind of camaraderie.

In this spirit, he wrote John Dos Passos in April 1925 about their mutual friend and co-writer Donald Ogden Stewart. The previous summer, they had all gone to the bullfights in Spain. Now Stewart was claiming to have outdrunk Dos Passos, Hemingway said, but this was nonsense. “Somebody has got to put that cheap lecturer in his place. He's claiming to be a drinker now. Remember how he vomited all over Pamplona? Drinker? Shit.” In fact Stewart was one of Hemingway's favorite drinking companions, as The Sun Also Rises illustrated. In that novel, Stewart served as the model for Bill Gorton, who spends a hilarious evening with Jake Barnes in Paris and later goes fishing with him prior to the fiesta. There the two of them make fun of various sacred cows of middle-class America, including prohibition. “Well,” Jake says. “The saloon must go.” “You're right there,” Bill agrees. “The saloon must go, and I will take it with me.”

For Hemingway, getting drunk represented good fun, and also served as a test of manhood. “I like to see every man drunk,” he observed in 1923. “A mandoes not exist until he is drunk.” In every possible way, Fitzgerald failed to meet his standards. With his limited tolerance for alcohol, he could not qualify as a worthy drinking companion. And when he did get drunk, he made a nuisance of himself instead of contributing to the high spirits of the occasion.

Ernest liked his wives to drink along with him, for that way his own drinking seemed less like an aberration. All of them—with the exception of Martha Gellhorn— learned to keep him company with the bottle. Even Agnes, who had previously never touched liquor, knocked back a couple of whiskeys to please him. Hadley showed “considerable promise” as a drinker from the start. During their years in Paris, she developed an iron constitution of her own. As a regular practice, they each consumed a bottle of wine with lunch, followed by aperitifs before dinner and another two bottles with the meal. They figured that they could burn off the effects of the alcohol with regular exercise, in hour-long walks around Paris or hikes in the mountains.

For many years, this regimen seemed to work for Hemingway. He drank a great deal, and was able through vigorous exercise to counteract unpleasant aftereffects. In an August 1929 letter to Maxwell Perkins, he expounded on this process. They had both heard about famous drinkers of the past, he wrote, but those three- and four-bottle men “were living all the time in the open air—hunting, shooting, always on a horse.” Living that way, you could “drink any amount.” The fresh air would oxidize the alcohol. For himself at that time, living in Paris and at his desk most of the day, boxing in the gym enabled him to sweat the liquor out of his system. Soon thereafter, Hemingway moved to Key West where he could spend more of his time outdoors on the water, and test his dubious “fresh air” theory by drinking still more.

Fond of the bottle Hemingway assuredly was. During the middle and late 1930s, he celebrated the wondrous effects of liquor in his correspondence and in his published writing. In Green Hills of Africa (1935), he meets an Austrian intellectual in Africa who cannot understand why Hemingway should place so much importance on drinking. It had always seemed a weakness to him, the Austrian said. “It is a way of ending a day,” Hemingway objected. “It has great benefits. Don't you ever want to change your ideas?” He elaborated on those benefits in a letter to Ivan Kashkin, a young Russian critic who admired Hemingway's writing. “I notice you speak slightingly of the bottle,” Ernest observed, and went on to explain why Kashkin was wrong to do so.

I have drunk since I was fifteen and few things have given me more pleasure. When you work hard all day with your head and know youmust work again the next day what else can change your ideas and make them run on a different plane like whisky? When you are cold and wet what else can warm you? Before an attack who can say anything that gives you the momentary well being that rum does? I would as soon not eat at night as not to have red wine and water.

Alcohol, in short, was essential to his work and his well-being, as indispensable as food or shelter—and a source of great pleasure.

Having praised whiskey and rum and red wine to Kashkin, Hemingway went on to deliver a remarkable encomium to absinthe in For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). According to the protagonist Robert Jordan, who is fighting a guerilla war in Spain, absinthe had the power to bring back the happiest memories of happier times. One cup of it

took the place of the evening papers, of all the old evenings in cafes, of all chestnut trees that would be in bloom now in this month, of the great slow horses of the outer boulevards, of book shops, of kiosques, and of galleries… and of being able to read and relax in the evening, of all the things he had enjoyed and forgotten and that came back to him when he tasted that opaque, bitter, tongue-numbing, brain-warming, stomach-warming, idea-changing liquid alchemy.

He could still drink vast quantities without drastic consequences, Ernest bragged in a February 1940 letter to Perkins. He'd gotten drunk the night before, he admitted. “Started out on absinthe, drank a bottle of good red wine with dinner, shifted to vodka in town… and then battened it down with whiskys and sodas until 3 a.m. Feel good today. But not like working.” In fact the liquor was making inroads, changing not only “ideas” but actions. At a fortieth birthday party given for him in Cuba on July 21, 1939, Hemingway got completely drunk and behaved very much like Fitzgerald at the Murphys' a decade and a half earlier. He threw his host's clothes out the window, and began breaking his Baccarat crystal glasses.

Writing Fitzgerald during those years, Hemingway made it clear that he regarded drinking as something that could be controlled by an act of will. He scolded Scott for getting “stinking drunk” during their 1933 dinner with Wilson and for humiliating all three of them with his combination of excessive praise followed by vicious insult. He assumed that Fitzgerald acted that way deliberately. Why didn't he put a stop to it?

Ernest thought that he could quit drinking at any time, but knew he didn't want to. The trouble was, as he wrote Archibald MacLeish in December 1943, that throughout his life “when things were really bad he could take a drink and right away they were much better.” While serving as a war correspondent in Europe two years later, he wrote his fourth wife Mary Welsh that he hadn't had any liquor for two days. “[Y]ou'll be happy to know that I am all the same without it as with it—think maybe steadier and better—although I have loved it, needed it, and many times it has saved one's damned reason, self-respect, and whatall… We always called it the Giant Killer and nobody who has not had to deal with the Giant many, many times has any right to speak against the Giant Killer.” He reiterated the point in a 1950 letter to Arthur Mizener contrasting his drinking habit with Fitzgerald's. “[A]lcohol, that we use as the Giant Killer, and that I could not have lived without many times; or at least would not have cared to live without; was a straight poison to Scott instead of a food.”

The Giant Hemingway had in mind, almost certainly, was the depression that periodically overtook him—an inherited malady that started early and that he was never able to escape. When Hemingway repeatedly praised alcohol for its ability to “change ideas,” he meant that it could at least temporarily shut down the darkness. As early as “The Three-Day Blow,” a story of 1924, he celebrated liquor for its ability to make things seem “much better.” In that story, Nick gets drunk and manages to dispel his unhappiness at having broken up with his girlfriend. Under the influence, “the Marge business was no longer so tragic. It was not even very important.” How he would feel the next day was another matter, but he could always call on alcohol to perform its magic in the ongoing cycle. What was true of the character Nick Adams in 1924 came to pass for his creator a quarter of a century later. By that time, according to Ernest's son Patrick, his father would succumb to depression whenever he was deprived of liquor.

In 1949, Hemingway wrote magazine writer A.E. Hotchner that drinking was “fun, not a release from something,” an assertion that flatly contradicted the need to kill the Giant letter he had written MacLeish six years earlier. There was a reason why he had arrived at this opinion, as the letter to Hotchner went on to reveal. Those who needed drink as “a release from something,” he explained, got to be rummies. He had spent much of his life straightening out rummies and all of his life drinking, but since writing was his true love he never got “the two things mixed up.” Scott Fitzgerald was one of the rummies he had in mind. Reading Tender Is the Night, he claimed, he could tell precisely when Fitzgerald started hitting the bottle. He could spot it in Faulkner as well. He himself would never let drinking “mix up” or contaminate his writing.

This was a classic case of denial, for Hemingway did need alcohol as “a release” from his depression. Moreover, his writing was affected by liquor—and had been since the books of the 1930s on bullfighting in Spain and big-game hunting in Africa in which, as Edmund Wilson observed, he seemed to be engaged in “a deliberate self-drugging.” By 1949, when Lillian Ross wrote her long profile of him in the New Yorker, Ernest was manifestly in the grip of alcoholism. Ross followed him around New York for a couple of days, as he exhibited various signs of his addiction. He drank heroic amounts of booze, held forth on any number of subjects in a sub-literate patois, and—most tellingly-put on an exhibition of grandiosity by comparing himself, favorably, with great writers of the past. Ross's portrait contributed to the legend of Hemingway as a man of action—no pantywaist aesthete, he—who downed world-record draughts as regularly as he attended wars. In the 1950s, guidebooks to Europe started listing his favorite watering holes as places for travelers to visit—Harry's Bar in Venice, the Ritz in Paris, Chicote's in Madrid. There are other famous saloons in this hemisphere associated with Hemingway, notably Sloppy Joe's in Key West and the Floridita in Havana, the home of the Papa Doble, or double daiquiri. All became tourist destinations because Ernest Hemingway drank there.

This part of the legend reached its nadir in Across the River and Into the Trees, Hemingway's talky novel about fifty-year-old Colonel Richard Cantwell and Renata, his nineteen-year-old Italian mistress. Most of the major characters in Hemingway's novels were drinkers, but Cantwell outdid the rest. Tom Dardis kept track of one day's consumption by Cantwell in The Thirsty Muse, his groundbreaking study of drinking among twentieth-century American authors. Upon arrival in Venice one afternoon, the colonel warms up with two gin and camparis, three very dry double martinis, and three even dryer Montgomerys (martinis made fifteen parts gin to one part vermouth). At dinner, he shares a bottle of Capri Bianco, two bottles of Valpolicella, and two bottles of champagne with his adoring young lover. He takes along another bottle of Valpolicella to drink in the gondola where he makes love to Renata at least twice. The next morning, Cantwell wakes up at first light without a trace of a hangover.

On the surface, this catalogue of the colonel's consumption—more than a quart of alcohol over the space of six or seven hours, without losing mental or sexual powers—seems almost comical in its excess. Who could believe it? What Dardis suggests, however, is that in Across the River and Into the Trees Hemingway was in substance portraying reality as he then knew it. He was himself fifty years old, in love with Adriana Ivancich, a nineteen-year-old Venetian, and—according to his Cuban doctor, José Luis Herrera Sotolongo —always drunk. “If you keep on drinking this way,” Herrera Sotolongo warned Ernest, “you won't even be able to write your name.” It was a bad time in the marriage as well, for Ernest and Mary were constantly fighting. At one stage the doctor removed all guns from the Hemingways' house. They were threatening to shoot each other.

At the end of their African safari in 1953-1954, Hemingway was badly wounded in two plane crashes. A number of newspapers incorrectly reported that he had been killed, but his injuries were so severe that he turned to the Giant Killer for relief.

His oldest son Jack came to visit Ernest at his finca in Cuba in 1955, and the two men got drunk together. Hemingway decided that they should reduce the population of buzzards around the place. Armed with shotguns and pitchers of martinis, they mounted to the tower above his workroom and started blazing away. After three pitchers and much hilarity, Ernest called a cease-fire and they repaired to the main house. Mary slammed her door, disgusted by the wholesale slaughter. Father and son continued their drinking as they viewed Ernest's print of Casablanca. “Isn't the Swede beautiful?” Ernest asked Jack, who responded that in his eyes too Ingrid Bergman looked “really, truly… beautiful.” Her beauty was too much for them, in their maudlin state, and they both dissolved in tears. That drunken afternoon, Jack remembered, was the closest he'd ever felt to his father.

At about the same time, Hemingway formed an epistolary friendship with the great art connoisseur Bernard Berenson at Villa i Tatti outside Florence. Ernest's “rambling and affectionate” letters must have been written under the influence of alcohol, the eighty-nine-year-old Berenson intuited. He looked forward to Hemingway's impending visit “with a certain dread.” He was afraid that Ernest in the flesh might prove “too overwhelmingly masculine” and that he might expect Berenson “to drink and guzzle with him.” The visit did not take place. Ernest became ill in Venice and did not make the journey to Florence.

During the last decade of his life, Hemingway was often ill. In November 1955, for example, he came down with an attack of hepatitis. Herrera Sotolongo put him on a daily ration of two ounces of whiskey, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, that Ernest adhered to for a time. He also did some reading about hepatitis in a book, The Liver and Its Diseases. He underlined a number of passages in the book, including one that told him what he wanted to hear, that “the apparent connection between hepatic fibrosis and alcoholism can more easily be explained as a result of malnutrition than as a consequence of alcohol.” Good diet and exercise could prevent cirrhosis, Dr. Herrera Sotolongo alsobelieved, and that was what he prescribed. Hemingway suffered another attack of viral hepatitis, but did not develop cirrhosis of the liver.

Soon he resumed drinking heavily. According to A.E. Hotchner, in 1956 Ernest drank Scotch or red wine nightly, and “was invariably in bad shape when finally induced to go to his room.” Daytimes, he sat for hours rooted in one position, “sipping his drinks and talking, first coherently, then as the alcohol dissolved all continuity, his talk becoming repetitive, his speech slurred and disheveled.” The verbal picture captured Hemingway in the worst of condition, immobilized by drink. For many years, Hemingway had been able to handle liquor and continue to function, but no longer. He could still boast to Hotchner that he had “been drunk 1,547 times in [his] life, but never in the morning.” And he could still wake up and declare that he'd gone “five rounds with Demon Rum last night and knocked him on his ass in one fifty-five of the sixth.” But he could not make it to lunch without some restorative tequila or vodka. He had crossed “the great divide,” as Gingrich put it, “between great drinkers and great drunks.” In March 1957 Dr. Jean Monnier, the ship's doctor on the Ile de France, instructed Hemingway that painful though it might be, in order to survive he had to “stop drinking alcohol.” This Ernest could not do. Staying cold sober made him dull. He felt like a racing car without oil.

In his book Alcohol and the Writer, Dr. Donald W. Goodwin asserts that there was reason to believe that Hemingway was diagnosed as a manic-depressive during his stay at the Mayo Clinic in 1961. He underwent shock treatment there, and—seemingly better—was sent home to Ketchum, Idaho, where he killed himself early on the morning of July 2. He had many things wrong with him, physically. He suffered from high blood pressure, liver and kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemochromatosis. His cholesterol count was 380. His liver bulged out against his body, George Plimpton said, “like a long, fat leech.” Mentally, he had become paranoid, convinced that various federal authorities were on his trail and that those who pretended to be friends were plotting against him. Alcohol contributed to many of these conditions, as it played a role in interaction with the worst condition of all, the depression that drove him to place the shotgun against his head and trip both barrels.

“One problem with heavy drinkers,” Goodwin observes, “is that they become depressed and one never knows whether drinking causes the depression or depression causes the drinking. Psychiatrists agree that a heavy drinker must stop drinking before a diagnosis can be made.” Well, Hemingway stopped drinking during the last months of his life and then committed suicide. This makes it possible to conclude, without much conviction, that it was the depression that caused the alcoholism that relieved the depression as it worked its own insidious deadly way into the system. In a family beset by suicides—Ernest's father's, his own, his brother's, at least one sister's, his granddaughter's—the suggestion is strong that Ernest Hemingway took his own life because he was depressed. For many years alcohol offered him temporary relief from his attacks of the “black ass,” while in the long run exacerbating his mental and physical woes. Hemingway died a ruined writer and a desperately sick man, convinced that life was not worth the living. In large part, that conviction derived from the Giant Killer.

A Writers' Disease

In his Natural History of Alcoholism, Dr. George Vaillant defined alcoholism as a disease in which “loss of voluntary control over alcohol consumption becomes a necessary and sufficient cause for much of an individual's social, psychological, and physical morbidity.” The way in which the disease developed and its outward manifestations varied markedly from one person to another, as in the cases of Fitzgerald and Hemingway. But there can be no doubt that both of them were in the grip of alcohol, and could not shake free of it short of the grave. In their misfortune, they joined a host of American writers of the early and middle twentieth century. Alcoholism among these writers, Goodwin asserted, constituted an “epidemic.” Among others the roster includes E.A. Robinson, Dreiser, Stephen Crane, London, Hart Crane, O'Neill, Lardner, Lewis, Faulkner, Wolfe, Millay, Parker, Benchley, Thurber, O'Hara, Steinbeck, Hammett, Chandler, Cummings, Roethke, Berryman, Tennessee Williams, Inge, Capote, Saroyan, Aiken, Kerouac, Agée, James Jones, Lowell, Jarrell, Sexton, Cheever, Stafford, and Carver. Excessive drinking, it seemed clear, was an occupational hazard. According to Goodwin only bartenders had higher rates of alcoholism than writers.

One reason for the epidemic was the epidemic itself. If all these great writers were drunks, didn't it follow that you had to drink to be a great writer? Fitzgerald embraced that notion when he challenged a correspondent to “name a single American artist except James & Whistler [both of whom lived in England] who didn't die of drink.” American culture came to expect such self-destruction from its artists. As the poet Donald Hall expressed it, “[t]here seems to be an assumption, widely held and all but declared, that it is natural to want to destroy yourself.” This pernicious doctrine encouraged young writers to emulate theBerrymans and O'Neills and Fitzgeralds by drinking themselves into insensibility while “consumers of vicarious death” sat on the sidelines and applauded. The applause, Hall felt, should be reserved for writers who survived. Self-destruction was no sure sign of genius, and genius no excuse for self-destruction.

A number of other explanations have been offered for the phenomenon of the drunken writer in America. Goodwin presented several of them in Alcohol and the Writer.

“Writing is a form of exhibitionism; alcohol lowers inhibitions and prompts exhibitionism in many people. Writing requires an interest in people; alcohol increases sociability and makes people more interesting. Writing involves fantasy; alcohol promotes fantasy. Writing requires self-confidence; alcohol bolsters confidence. Writing is lonely work; alcohol assuages loneliness. Writing demands intense concentration; alcohol relaxes.” Most of these motivating factors seem to fit Fitzgerald's case better than Hemingway's, particularly the release from inhibitions (the “stimulus” of liquor) and the access of sociability.

Alcohol's effect on social relations constituted the first of the three reasons Malcolm Cowley cited for drinking among writers. Cowley's observations carry a certain authority, for as a poet, critic, and editor, he had an unusually wide acquaintance among the century's greatest writers. His three “special reasons,” in abbreviated form, were: 1) “Writers are probably shyer, on the average, than members of other professions… and at the same time they are more eager to establish direct personal communications. Alcohol serves, or appears to serve, as a bridge between person and person.” 2) “Writing is an activity that involves a high degree of nervous tension, and alcohol is a depressant that helps to soothe the nerves.” 3) “For many writers drinking becomes part of the creative process. They drink in order to have visions, or in order to experience the feeling of heightened life that they are trying to convey… or in order to get in touch with their subconscious minds… or in order to overcome their excessive obedience to the inner censor, or simply in order to start the flow of words.” Or, the cynic is tempted to add, for almost any other reason that will give them leave to drink.

The novelist Walker Percy, himself a doctor, presented yet another problem confronting writers: the problem of “reentry” after exaltation. “What goes up must come down. The best film of the year ends at nine o'clock. What to do at ten? What did Faulkner do after writing the last sentence of The Sound and the Fury? Get drunk for a week. What did Dostoyevsky do after finishing The ldiot? Spend three days and nights at the roulette table. What does the reader do after finishing either book? How long does his exaltation last?”

As the questions make clear, “reentry” poses difficulties for everyone. In Percy's formulation, these are “most spectacular” for writers, who “seem subject more than most people to estrangement from the society around them, to neurosis, psychosis, alcoholism, drug addiction, epilepsy, florid sexual behavior, solitariness, depression, violence, and suicide.” They retreat into art, as Einstein did into science, “to escape the intolerable dreariness of everyday life.” But the escape can never be complete. As Percy posed the dilemma, “How do you go about living in the world when you are not working at your art, yet still find yourself having to get through a Wednesday afternoon?”

Combining physiological and psychological thinking, Percy arrived at a persuasive account of “Why a Writer Drinks.”

He is marooned in his cortex. Therefore it is his cortex that he must assault. Worse, actually. He, his self, is marooned in his left cortex… Yet his work, if he is any good, comes from listening to his right brain, locus of the unconscious knowledge of the fit and form of things. So, unlike the artist who can fool and cajole his right brain and get it going by messing in paints and clay and stone… there sits the poor writer, rigid as a stick, pencil poised, with no choice but to wait in fear and trembling until the spark jumps the commissure. Hence his notorious penchant for superstition and small obsessive and compulsive acts such as lining up paper exactly foursquare with desk. Then, failing in these frantic invocations and after the right brain falls as silent as the sphinx—what else can it do?—nothing remains, if the right won't talk, but to assault the left with alcohol, which of course is a depressant and which does of course knock out that grim angel guarding the gate of Paradise and let the poor half-brained writer in and a good deal besides. But by now the writer is drunk, his presiding left-brained craftsman-consciousness laid out flat, trampled by the rampant imagery from the right and a horde of reptilian demons from below.

For all these many reasons, then, writers turn to alcohol. But there are those who turn back, too, among them in recent times John Cheever and Raymond Carver. In fall 1973 they were colleagues and alcoholics together at the University of Iowa's writers workshop. Carver used to drive Cheever to the liquor store so they could be there when it opened. Neither of them took the cover off his typewriter the entire autumn. But somehow Cheever stoppeddrinking, sobered up, wrote Falconer, and received the homage due him before his death in 1982. Carver quit in 1978, and survived for ten more productive years. “Don't weep for me,” he told his friends when he was dying. He'd lived ten years longer than he expected, and those years were “all gravy.”

The novelist and newspaperman Pete Hamill wrote about his alcoholism in his 1994 memoir, A Drinking Life. In his boyhood, he used to go to Gallagher's saloon with his father. Billy Hamill was the star of the place, singing Irish songs and commanding the attention and admiration of the other drinkers. “This is where men go,” Pete thought, “this is what men do.” Unlike his father he did not sing, but he knew how to tell stories, and he told a lot of them in one saloon or another that served as his nightly home away from home—and wife and children. In December 1973, he was standing at a bar making epigrams and telling jokes and repeating lines that had gotten laughs from others when it suddenly struck him that he “was performing [his] life instead of living it.” If this was a play, he wanted a better part. Hamill quit drinking then, and to help him stick to that decision adopted a mantra: “I will live my life from now on, I will not perform it.”

When people asked him why he didn't drink, he'd say, “I have no talent for it.” Sober, he found he had more time for his family and for his writing. And he no longer had to spend the hangover days lacerating himself for crimes and misdemeanors of the night before. “No more apologies for stupid phone calls, asinine remarks, lapses in grace.” In Hollywood, he met out-of-work directors and screenwriters and actors, all ruined by booze. He could not help thinking of “some of the final tortured stories by Scott Fitzgerald,” another alcoholic of Irish heritage, another histrionic drunk, another chronic apologizer. He felt “a surge of pity” for him, struck down in his early forties. But pity is not strong enough for what Fitzgerald left undone and what Hemingway could no longer do as drink took over their lives. We cannot know exactly what was lost— only that the loss was immense, and irrecoverable.

Whoever won the battle between Scott and Ernest for writer of his generation, they both lost the war to alcoholism.

Sources

Fitzgerald's Case