Mightier than the Sword

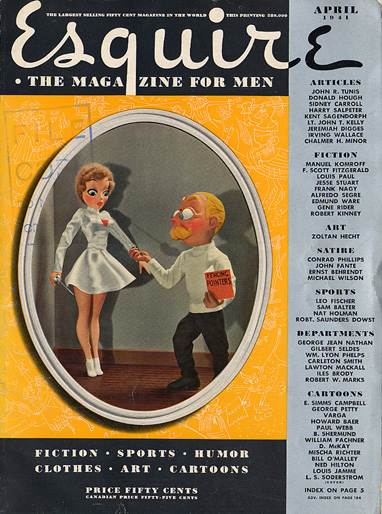

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

I

The swarthy man, with eyes that snapped back and forward on a rubber band from the rear of his head, answered to the alias of Dick Dale. The tall, spectacled man who was put together like a camel without a hump—and you missed the hump—answered to the name of E. Brunswick Hudson. The scene was a shoeshine stand, insignificant unit of the great studio. We perceive it through the red-rimmed eyes of Pat Hobby who sat in the chair beside Director Dale.

The stand was out of doors, opposite the commissary. The voice of E. Brunswick Hudson quivered with passion but it was pitched low so as not to reach passers-by.

“I don’t know what a writer like me is doing out here anyhow,” he said, with vibrations.

Pat Hobby, who was an old-timer, could have supplied the answer, but he had not the acquaintance of the other two.

“It’s a funny business,” said Dick Dale, and to the shoe-shine boy, “Use that saddle soap.”

“Funny!” thundered E., “It’s SUS-pect! Here against my better judgement I write just what you tell me—and the office tells me to get out because we can’t seem to agree.”

“That’s polite,” explained Dick Dale. “What do you want me to do—knock you down?”

E. Brunswick Hudson removed his glasses.

“Try it!” he suggested. “I weigh a hundred and sixty-two and I haven’t got an ounce of flesh on me.” He hesitated and redeemed himself from this extremity. “I mean FAT on me.”

“Oh, to hell with that!” said Dick Dale contemptuously, “I can’t mix it up with you. I got to figure this picture. You go back East and write one of your books and forget it.” Momentarily he looked at Pat Hobby, smiling as if HE would understand, as if anyone would understand except E. Brunswick Hudson. “I can’t tell you all about pictures in three weeks.”

Hudson replaced his spectacles.

“When I DO write a book,” he said, “I’ll make you the laughing stock of the nation.”

He withdrew, ineffectual, baffled, defeated. After a minute Pat spoke.

“Those guys can never get the idea,” he commented. “I’ve never seen one get the idea and I been in this business, publicity and script, for twenty years.”

“You on the lot?” Dale asked.

Pat hesitated.

“Just finished a job,” he said.

That was five months before.

“What screen credits you got?” Dale asked.

“I got credits going all the way back to 1920.”

“Come up to my office,” Dick Dale said, “I got something I’d like to talk over—now that bastard is gone back to his New England farm. Why do they have to get a New England farm—with the whole West not settled?”

Pat gave his second-to-last dime to the bootblack and climbed down from the stand.

II

We are in the midst of technicalities.

“The trouble is this composer Reginald de Koven didn’t have any colour,” said Dick Dale. “He wasn’t deaf like Beethoven or a singing waiter or get put in jail or anything. All he did was write music and all we got for an angle is that song O Promise Me. We got to weave something around that—a dame promises him something and in the end he collects.”

“I want time to think it over in my mind,” said Pat. “If Jack Berners will put me on the picture—”

“He’ll put you on,” said Dick Dale. “From now on I’m picking my own writers. What do you get—fifteen hundred?” He looked at Pat’s shoes, “Seven-fifty?”

Pat stared at him blankly for a moment; then out of thin air, produced his best piece of imaginative fiction in a decade.

“I was mixed up with a producer’s wife,” he said, “and they ganged up on me. I only get three-fifty now.”

In some ways it was the easiest job he had ever had. Director Dick Dale was a type that, fifty years ago, could be found in any American town. Generally he was the local photographer, usually he was the originator of small mechanical contrivances and a leader in bizarre local movements, almost always he contributed verse to the local press. All the most energetic embodiments of this “Sensation Type” had migrated to Hollywood between 1910 and 1930, and there they had achieved a psychological fulfilment inconceivable in any other time or place. At last, and on a large scale, they were able to have their way. In the weeks that Pat Hobby and Mabel Hatman, Mr Dale’s script girl, sat beside him and worked on the script, not a movement, not a word went into it that was not Dick Dale’s coinage. Pat would venture a suggestion, something that was “Always good”.

“Wait a minute! Wait a minute!” Dick Dale was on his feet, his hands outspread. “I seem to see a dog.” They would wait, tense and breathless, while he saw a dog.

“Two dogs.”

A second dog took its place beside the first in their obedient visions.

“We open on a dog on a leash—pull the camera back to show another dog—now they’re snapping at each other. We pull back further—the leashes are attached to tables—the tables tip over. See it?”

Or else, out of a clear sky.

“I seem to see De Koven as a plasterer’s apprentice.”

“Yes.” This hopefully.

“He goes to Santa Anita and plasters the walls, singing at his work. Take that down, Mabel.” He continued on…

In a month they had the requisite hundred and twenty pages. Reginald de Koven, it seemed, though not an alcoholic, was too fond of “The Little Brown Jug”. The father of the girl he loved had died of drink, and after the wedding when she found him drinking from the Little Brown Jug, nothing would do but that she should go away, for twenty years. He became famous and she sang his songs as Maid Marian but he never knew it was the same girl.

The script, marked “Temporary Complete. From Pat Hobby” went up to the head office. The schedule called for Dale to begin shooting in a week.

Twenty-four hours later he sat with his staff in his office, in an atmosphere of blue gloom. Pat Hobby was the least depressed. Four weeks at three-fifty, even allowing for the two hundred that had slipped away at Santa Anita, was a far cry from the twenty cents he had owned on the shoeshine stand.

“That’s pictures, Dick,” he said consolingly. “You’re up—you’re down—you’re in, you’re out. Any old-timer knows.”

“Yes,” said Dick Dale absently. “Mabel, phone that E. Brunswick Hudson. He’s on his New England farm—maybe milking bees.”

In a few minutes she reported.

“He flew into Hollywood this morning, Mr Dale. I’ve located him at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.”

Dick Dale pressed his ear to the phone. His voice was bland and friendly as he said:

“Mr Hudson, there was one day here you had an idea I liked. You said you were going to write it up. It was about this De Koven stealing his music from a sheepherder up in Vermont. Remember?”

“Yes.”

“Well, Berners wants to go into production right away, or else we can’t have the cast, so we’re on the spot, if you know what I mean. Do you happen to have that stuff?”

“You remember when I brought it to you?” Hudson asked. “You kept me waiting two hours—then you looked at it for two minutes. Your neck hurt you—I think it needed wringing. God, how it hurt you. That was the only nice thing about that morning.”

“In picture business—”

“I’m so glad you’re stuck. I wouldn’t tell you the story of The Three Bears for fifty grand.”

As the phones clicked Dick Dale turned to Pat.

“Goddam writers!” he said savagely. “What do we pay you for? Millions—and you write a lot of tripe I can’t photograph and get sore if we don’t read your lousy stuff! How can a man make pictures when they give me two bastards like you and Hudson. How? How do you think—you old whiskey bum!”

Pat rose—took a step toward the door. He didn’t know, he said.

“Get out of here!” cried Dick Dale. “You’re off the payroll. Get off the lot.”

Fate had not dealt Pat a farm in New England, but there was a cafй just across from the studio where bucolic dreams blossomed in bottles if you had the money. He did not like to leave the lot, which for many years had been home for him, so he came back at six and went up to his office. It was locked. He saw that they had already allotted it to another writer—the name on the door was E. Brunswick Hudson.

He spent an hour in the commissary, made another visit to the bar, and then some instinct led him to a stage where there was a bedroom set. He passed the night upon a couch occupied by Claudette Colbert in the fluffiest ruffles only that afternoon.

Morning was bleaker, but he had a little in his bottle and almost a hundred dollars in his pocket. The horses were running at Santa Anita and he might double it by night.

On his way out of the lot he hesitated beside the barber shop but he felt too nervous for a shave. Then he paused, for from the direction of the shoeshine stand he heard Dick Dale’s voice.

“Miss Hatman found your other script, and it happens to be the property of the company.”

E. Brunswick Hudson stood at the foot of the stand.

“I won’t have my name used,” he said.

“That’s good. I’ll put her name on it. Berners thinks it’s great, if the De Koven family will stand for it. Hell—the sheepbreeder never would have been able to market those tunes anyhow. Ever hear of any sheepherder drawing down jack from ASCAP?”

Hudson took off his spectacles.

“I weigh a hundred and sixty-three—”

Pat moved in closer.

“Join the army,” said Dale contemptuously, “I got no time for mixing it up. I got to make a picture.” His eyes fell on Pat. “Hello old-timer.”

“Hello Dick,” said Pat smiling. Then knowing the advantage of the psychological moment he took his chance.

“When do we work?” he said.

“How much?” Dick Dale asked the shoeshine boy—and to Pat, “It’s all done. I promised Mabel a screen credit for a long time. Look me up some day when you got an idea.”

He hailed someone by the barber shop and hurried off. Hudson and Hobby, men of letters who had never met, regarded each other. There were tears of anger in Hudson’s eyes.

“Authors get a tough break out here,” Pat said sympathetically. “They never ought to come.”

“Who’d make up the stories—these feebs?”

“Well anyhow, not authors,” said Pat. “They don’t want authors. They want writers—like me.”

Published in Esquire magazine (April 1941).

Not illustrated.