Pat Hobby’s Preview

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

I

“I haven’t got a job for you,” said Berners. “We’ve got more writers now than we can use.”

“I didn’t ask for a job,” said Pat with dignity. “But I rate some tickets for the preview tonight—since I got a half credit.”

“Oh yes, I want to talk to you about that,” Berners frowned. “We may have to take your name off the screen credits.”

“WHAT?” exclaimed Pat. “Why, it’s already on! I saw it in the Reporter. ‘By Ward Wainwright and Pat Hobby.’”

“But we may have to take it off when we release the picture. Wainwright’s back from the East and raising hell. He says that you claimed lines where all you did was change ‘No’ to ‘No sir’ and ‘crimson’ to ‘red’, and stuff like that.”

“I been in this business twenty years,” said Pat. “I know my rights. That guy laid an egg. I was called in to revise a turkey!”

“You were not,” Berners assured him. “After Wainwright went to New York I called you in to fix one small character. If I hadn’t gone fishing you wouldn’t have got away with sticking your name on the script.” Jack Berners broke off, touched by Pat’s dismal, red-streaked eyes. “Still, I was glad to see you get a credit after so long.”

“I’ll join the Screen Writers Guild and fight it.”

“You don’t stand a chance. Anyhow, Pat, your name’s on it tonight at least, and it’ll remind everybody you’re alive. And I’ll dig you up some tickets—but keep an eye out for Wainwright. It isn’t good for you to get socked if you’re over fifty.”

“I’m in my forties,” said Pat, who was forty-nine.

The Dictograph buzzed. Berners switched it on.

“It’s Mr Wainwright.”

“Tell him to wait.” He turned to Pat: “That’s Wainwright. Better go out the side door.”

“How about the tickets?”

“Drop by this afternoon.”

To a rising young screen poet this might have been a crushing blow but Pat was made of sterner stuff. Sterner not upon himself, but on the harsh fate that had dogged him for nearly a decade. With all his experience, and with the help of every poisonous herb that blossoms between Washington Boulevard and Ventura, between Santa Monica and Vine—he continued to slip. Sometimes he grabbed momentarily at a bush, found a few weeks’ surcease upon the island of a “patch job”, but in general the slide continued at a pace that would have dizzied a lesser man.

Once safely out of Berners’ office, for instance, Pat looked ahead and not behind. He visioned a drink with Louie, the studio bookie, and then a call on some old friends on the lot. Occasionally, but less often every year, some of these calls developed into jobs before you could say “Santa Anita”. But after he had had his drink his eyes fell upon a lost girl.

She was obviously lost. She stood staring very prettily at the trucks full of extras that rolled toward the commissary. And then gazed about helpless—so helpless that a truck was almost upon her when Pat reached out and plucked her aside.

“Oh, thanks,” she said, “thanks, I came with a party for a tour of the studio and a policeman made me leave my camera in some office. Then I went to stage five where the guide said, but it was closed.”

She was a “Cute Little Blonde”. To Pat’s liverish eye, cute little blondes seemed as much alike as a string of paper dolls. Of course they had different names.

“We’ll see about it,” said Pat.

“You’re very nice. I’m Eleanor Carter from Boise, Idaho.”

He told her his name and that he was a writer. She seemed first disappointed—then delighted.

“A writer?… Oh, of course. I knew they had to have writers but I guess I never heard about one before.”

“Writers get as much as three grand a week,” he assured her firmly. “Writers are some of the biggest shots in Hollywood.”

“You see, I never thought of it that way.”

“Bernud Shaw was out here,” he said, “—and Einstein, but they couldn’t make the grade.”

They walked to the Bulletin Board and Pat found that there was work scheduled on three stages—and one of the directors was a friend out of the past.

“What did you write?” Eleanor asked.

A great male Star loomed on the horizon and Eleanor was all eyes till he had passed. Anyhow the names of Pat’s pictures would have been unfamiliar to her.

“Those were all silents,” he said.

“Oh. Well, what did you write last?”

“Well, I worked on a thing at Universal—I don’t know what they called it finally—” He saw that he was not impressing her at all. He thought quickly. What did they know in Boise, Idaho? “I wrote Captains Courageous,” he said boldly. “And Test Pilot and Wuthering Heights and—and The Awful Truth and Mr Smith Goes to Washington.”

“Oh!” she exclaimed. “Those are all my favourite pictures. And Test Pilot is my boy friend’s favourite picture and Dark Victory is mine.”

“I thought Dark Victory stank,” he said modestly. “Highbrow stuff,” and he added to balance the scales of truth, “I been here twenty years.”

They came to a stage and went in. Pat sent his name to the director and they were passed. They watched while Ronald Colman rehearsed a scene.

“Did you write this?” Eleanor whispered.

“They asked me to,” Pat said, “but I was busy.”

He felt young again, authoritative and active, with a hand in many schemes. Then he remembered something.

“I’ve got a picture opening tonight.”

“You HAVE?”

He nodded.

“I was going to take Claudette Colbert but she’s got a cold. Would you like to go?”

II

He was alarmed when she mentioned a family, relieved when she said it was only a resident aunt. It would be like old times walking with a cute little blonde past the staring crowds on the sidewalk. His car was Class of 1933 but he could say it was borrowed—one of his Jap servants had smashed his limousine. Then what? he didn’t quite know, but he could put on a good act for one night.

He bought her lunch in the commissary and was so stirred that he thought of borrowing somebody’s apartment for the day. There was the old line about “getting her a test”. But Eleanor was thinking only of getting to a hair-dresser to prepare for tonight, and he escorted her reluctantly to the gate. He had another drink with Louie and went to Jack Berners’ office for the tickets.

Berners’ secretary had them ready in an envelope.

“We had trouble about these, Mr Hobby.”

“Trouble? Why? Can’t a man go to his own preview? Is this something new?”

“It’s not that, Mr Hobby,” she said. “The picture’s been talked about so much, every seat is gone.”

Unreconciled, he complained, “And they just didn’t think of me.”

“I’m sorry.” She hesitated. “These are really Mr Wainwright’s tickets. He was so angry about something that he said he wouldn’t go—and threw them on my desk. I shouldn’t be telling you this.”

“These are HIS seats?”

“Yes, Mr Hobby.”

Pat sucked his tongue. This was in the nature of a triumph. Wainwright had lost his temper, which was the last thing you should ever do in pictures—you could only pretend to lose it—so perhaps his applecart wasn’t so steady. Perhaps Pat ought to join the Screen Writers Guild and present his case—if the Screen Writers Guild would take him in.

This problem was academic. He was calling for Eleanor at five o’clock and taking her “somewhere for a cocktail”. He bought a two-dollar shirt, changing into it in the shop, and a four-dollar Alpine hat—thus halving his bank account which, since the Bank Holiday of 1933, he carried cautiously in his pocket.

The modest bungalow in West Hollywood yielded up Eleanor without a struggle. On his advice she was not in evening dress but she was as trim and shining as any cute little blonde out of his past. Eager too—running over with enthusiasm and gratitude. He must think of someone whose apartment he could borrow for tomorrow.

“You’d like a test?” he asked as they entered the Brown Derby bar.

“What girl wouldn’t?”

“Some wouldn’t—for a million dollars.” Pat had had setbacks in his love life. “Some of them would rather go on pounding the keys or just hanging around. You’d be surprised.”

“I’d do almost anything for a test,” Eleanor said.

Looking at her two hours later he wondered honestly to himself if it couldn’t be arranged. There was Harry Gooddorf—there was Jack Berners—but his credit was low on all sides. He could do SOMETHING for her, he decided. He would try at least to get an agent interested—if all went well tomorrow.

“What are you doing tomorrow?” he asked.

“Nothing,” she answered promptly. “Hadn’t we better eat and get to the preview?”

“Sure, sure.”

He made a further inroad on his bank account to pay for his six whiskeys—you certainly had the right to celebrate before your own preview—and took her into the restaurant for dinner. They ate little. Eleanor was too excited—Pat had taken his calories in another form.

It was a long time since he had seen a picture with his name on it. Pat Hobby. As a man of the people he always appeared in the credit titles as Pat Hobby. It would be nice to see it again and though he did not expect his old friends to stand up and sing Happy Birthday to You, he was sure there would be back-slapping and even a little turn of attention toward him as the crowd swayed out of the theatre. That would be nice.

“I’m frightened,” said Eleanor as they walked through the alley of packed fans.

“They’re looking at you,” he said confidently. “They look at that pretty pan and try to think if you’re an actress.”

A fan shoved an autograph album and pencil toward Eleanor but Pat moved her firmly along. It was late—the equivalent of’ “all aboard” was being shouted around the entrance.

“Show your tickets, please sir.”

Pat opened the envelope and handed them to the doorman. Then he said to Eleanor:

“The seats are reserved—it doesn’t matter that we’re late.”

She pressed close to him, clinging—it was, as it turned out, the high point of her debut. Less than three steps inside the theatre a hand fell on Pat’s shoulder.

“Hey Buddy, these aren’t tickets for here.”

Before they knew it they were back outside the door, glared at with suspicious eyes.

“I’m Pat Hobby. I wrote this picture.”

For an instant credulity wandered to his side. Then the hard-boiled doorman sniffed at Pat and stepped in close.

“Buddy you’re drunk. These are tickets to another show.”

Eleanor looked and felt uneasy but Pat was cool.

“Go inside and ask Jack Berners,” Pat said. “He’ll tell you.”

“Now listen,” said the husky guard, “these are tickets for a burlesque down in L.A.” He was steadily edging Pat to the side. “You go to your show, you and your girl friend. And be happy.”

“You don’t understand. I wrote this picture.”

“Sure. In a pipe dream.”

“Look at the programme. My name’s on it. I’m Pat Hobby.”

“Can you prove it? Let’s see your auto licence.”

As Pat handed it over he whispered to Eleanor, “Don’t worry!”

“This doesn’t say Pat Hobby,” announced the doorman. “This says the car’s owned by the North Hollywood Finance and Loan Company. Is that you?”

For once in his life Pat could think of nothing to say—he cast one quick glance at Eleanor. Nothing in her face indicated that he was anything but what he thought he was—all alone.

III

Though the preview crowd had begun to drift away, with that vague American wonder as to why they had come at all, one little cluster found something arresting and poignant in the faces of Pat and Eleanor. They were obviously gate-crashers, outsiders like themselves, but the crowd resented the temerity of their effort to get in—a temerity which the crowd did not share. Little jeering jests were audible. Then, with Eleanor already edging away from the distasteful scene, there was a flurry by the door. A well-dressed six-footer strode out of the theatre and stood gazing till he saw Pat.

“There you are!” he shouted.

Pat recognized Ward Wainwright.

“Go in and look at it!” Wainwright roared. “Look at it. Here’s some ticket stubs! I think the prop boy directed it! Go and look!” To the doorman he said: “It’s all right! He wrote it. I wouldn’t have my name on an inch of it.”

Trembling with frustration, Wainwright threw up his hands and strode off into the curious crowd.

Eleanor was terrified. But the same spirit that had inspired “I’d do anything to get in the movies”, kept her standing there—though she felt invisible fingers reaching forth to drag her back to Boise. She had been intending to run—hard and fast. The hard-boiled doorman and the tall stranger had crystallized her feelings that Pat was “rather simple”. She would never let those red-rimmed eyes come close to her—at least for any more than a doorstep kiss. She was saving herself for somebody—and it wasn’t Pat. Yet she felt that the lingering crowd was a tribute to her—such as she had never exacted before. Several times she threw a glance at the crowd—a glance that now changed from wavering fear into a sort of queenliness.

She felt exactly like a star.

Pat, too, was all confidence. This was HIS preview; all had been delivered into his hands: his name would stand alone on the screen when the picture was released. There had to be somebody’s name, didn’t there?—and Wainwright had withdrawn.

SCREENPLAY BY PAT HOBBY.

He seized Eleanor’s elbow in a firm grasp and steered her triumphantly towards the door:

“Cheer up, baby. That’s the way it is. You see?”

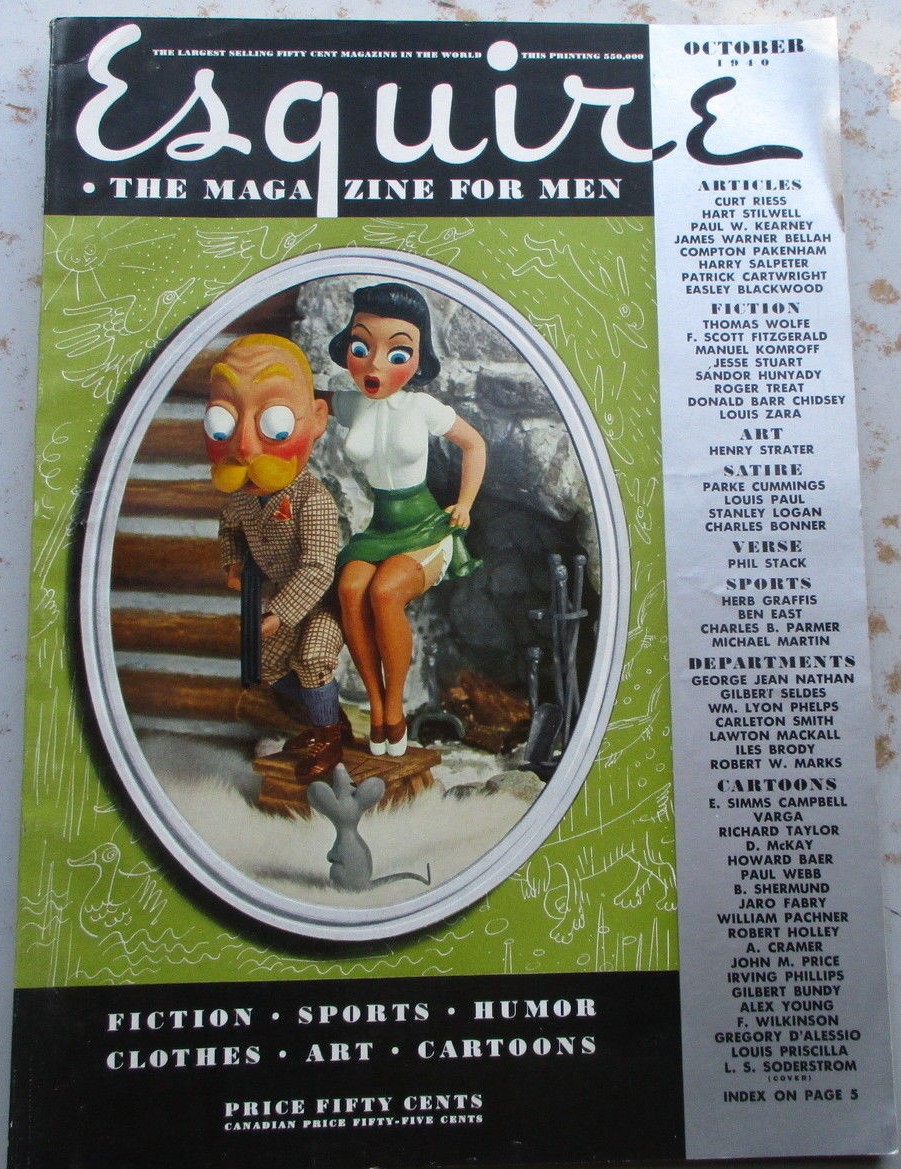

Published in Esquire magazine (October 1940).

Not illustrated.