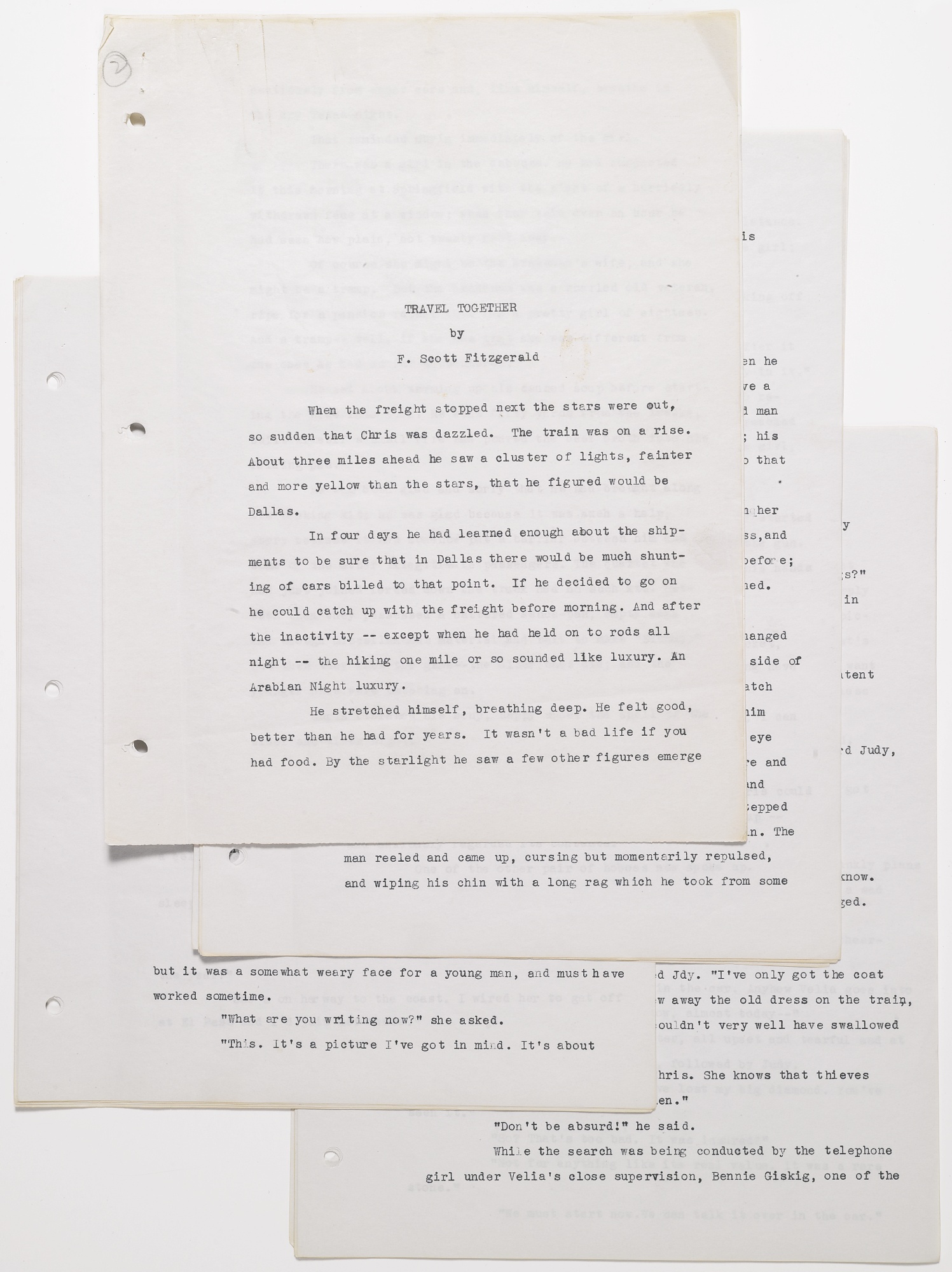

Travel Together

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

When the freight stopped next the stars were out, so sudden that Chris was dazzled. The train was on a rise. About three miles ahead he saw a cluster of lights, fainter and more yellow than the stars, that he figured would be Dallas.

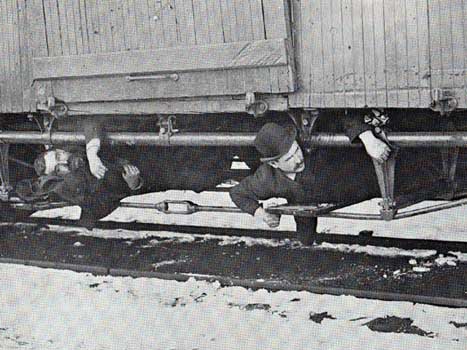

In four days he had learned enough about the shipments to be sure that in Dallas there would be much shunting of cars billed to that point. If he decided to go on he could catch up with the freight before morning. And after the inactivity—except when he had held on to rods all night—the hiking one mile or so sounded like luxury. An Arabian Night luxury.

He stretched himself, breathing deep. He felt good, better than he had for years. It wasn’t a bad life if you had food. By the starlight he saw a few other figures emerge cautiously from other cars and, like himself, breathe in the dry Texas night.

That reminded Chris immediately of the girl.

There was a girl in the caboose. He had suspected it this morning at Springfield with the sight of a hurriedly withdrawn face at a window; when they laid over an hour he had seen her plain, not twenty feet away.

Of course she might be the brakeman’s wife, and she might be a tramp. But the brakeman was a gnarled old veteran, ripe for a pension rather than for a pretty girl of eighteen. And a tramp—well, if she was that, she was different from the ones he had so far encountered.

He set about warming up his canned soup before starting the hike into town. He went fifty yards from the tracks, built himself a small fire and poured the beef broth into his folding pan.

He was both glad and sorry that he had brought along the cooking kit; he was glad because it was such a help, sorry because it had somehow put a barrier between him and some of the other illegitimate passengers. The quartet who had just joined forces down the track had no such kit. Between them they possessed a battered sauce-pan, empty cans and enough miscellaneous material and salt to make “Slummy.” But then they knew the game—the older ones did; and the younger ones were catching on.

Chris finished his soup, happy under the spell of the wider and wider night.

“Travel into those stars maybe,” he said aloud.

The train gave out a gurgle and a forlorn burst of false noise from somewhere, and with a clicking strain of couplers pulled forward a few hundred yards.

He made no move to rise. Neither did the tramps up the line make any move to board her again. Evidently they had the same idea he did, of catching it in Dallas. When the faintly lit caboose had gone fifty yards past him the train again jolted to a stop…

… The figure of a girl broke the faint light from the caboose door, slowly, tentatively. It—or she walked out to where the cindery roadside gave way to grass.

She gave every impression of wanting to remain alone—but this was not to be. No sooner had the four campers down the track caught sight of her than two of them got up and came over toward her. Chris finished the assemblage of his things and moved unobtrusively for the same spot. For all he knew they might be pals of the girl—on the other hand they had seemed to him a poor lot; in case of trouble he identified himself with the side on which they weren’t.

The things happened quicker than he had anticipated. There was a short colloquy between the men and the girl who obviously did not appreciate their company; presently one of them took her by the arm and attempted to force her in the direction of their camp. Chris sauntered nearer.

“What’s the idea?” he called over.

The men did not answer.

The girl struggled, gasping a little and Chris came closer.

“Hey, what’s the idea?” he called louder.

“Make them let me go! Make them—”

“Oh, shut your trap!”

But as Chris came up to the man who had spoken he dropped the girl’s arm and stood at a defiant defensive a few yards away. Chris was a well-built, well-preserved man just over thirty—the first tramp was young and husky; his companion existed under rolls of unexercised flesh, so that it was impossible to determine his value in battle.

The girl turned to Chris. The white glints in her eyes cracked the heavens as a diamond would crack glass, and let stream down a whiter light than he had ever seen before; it shone over a wide beautiful mouth, set and frightened.

“Make them go away! They tried this before!”

Chris was watching the two men. They had exchanged a look and were moving now, so that one was on either side of him. He backed up against the girl, murmuring, “You watch that side!” and catching his idea she stood touching him to guard against envelopment. From the corner of his eye Chris saw that the other two hoboes had left their fire and were running up. He acted quickly. When the stouter and elder of the tramps was less than a yard away, Chris stepped in and cracked him with a left to the right of his chin. The man reeled and came up, cursing but momentarily repulsed, and wiping his chin with a long rag which he took from some obscure section of his upholstery. But he kept his distance.

At that instant there was a wild cry from the girl: “He got my purse!”

—and Chris turned to see the younger man making off twenty feet, to grin derisively.

“Get my purse!” the girl cried. “They were after it last night. And I’ve got to have it! There’s no money in it.”

Wondering what she would have in her purse to regret so deeply Chris nonetheless came to a decision, reached into his swinging bundle and, standing in front of the girl, juggled a thirty-eight revolver in the starlight.

“Pull out that purse.”

The young man hesitated—he half turned, half started to run, but his eyes were mesmerized on the sight of the gun. He stopped in the moment of his pivot—instinctively his hands began to lift from his sides.

“Get that purse out!”

He had no fear of what the kid had in his pocket, knowing that the police or pawn-shop would long have frisked them of all weapons.

“He’s opening it in his pocket!” the girl cried, “I can see!”

“Throw it out!”

The purse ajar fell on the ground. Before Chris could stop her she had left him and run forward to pick it up—and anxiously regarded its contents.

One of the other pair of hoboes now spoke up.

“We didn’t mean any harm, brother. We said let the girl alone. Dint I, Joe?” He turned for confirmation, “I said let the girl alone, she’s in the caboose.”

Chris hesitated. His purpose was accomplished and—he still had four cans of food…

…Still he hesitated. They were four to one and the young man with a sub-Cromagnon visage, the one who’d stolen the purse, looked sore enough for a fight.

As bounty he extracted a can of corned beef and one of baked beans from his shrunken sack and tossed them.

“Get along now! I mean get along! You haven’t got a chance!”

“Who are you? A tec?”

“Never mind—get going. And if you want to eat this stuff—then travel half a mile!”

“Ain’t you got a little canned heat?”

“For you to drink? No I guess you got to make your own fire, like you did before.”

One man said in sing-song: “Git along, little doggie” and presently the quartet moved off beside the roadbed toward yellow-lit Dallas.

II

Crossing the two starlights there obtruded the girl.

Her face was a contrast between herself looking over a frontier—and a silhouette, and outline seen from a point of view, something finished—white, polite, unpolished—it was a destiny, scarred a little with young wars, worried with old white faiths…

…And out of it looked eyes so green that they were like phosphorescent marbles, so green that the scarcely dry clay of the face seemed dead beside it.

“Some other tramps took about everything else I had when I got off in St. Louis,” she said.

“Took what?”

“Took my money.” Her eyes glittered for him again in the starlight, “Who are you?”

“I'm just a man. Just a tramp like you. Where are you going?”

“All the way. The coast—Hollywood. Where you going?”

“Same place. You trying to get a job in pictures?”

The marble of her face was alive, flashing back the interest in his. “No, I’m going—because of this paper—this check.” She replaced it carefully in the purse. “You going to the movies?”

“I’m in ’em.”

“You mean you been working in them?”

“I’ve been in ’em a long time.”

“What are you doing on this road, then?”

“Lady! I didn’t mean to tell this to anybody, but I write them—believe it or not. I’ve written many a one.”

She did not care whether or not he had but the very implausibility overwhelmed her.

“You’re on the road—like me.”

“Why are you on the road?”

“For a reason.”

He took a match out of his rucksack—and simultaneously his last can of soup knocked against him.

“Have a bite with me?”

“No thanks. I’ve eaten.”

But there was that wan look about her—

“Have you eaten?” he reiterated.

“Sure, I have… So you’re a writer in Hollywood.”

He moved around collecting twigs to start a fire for the last can of soup and he saw two pieces of discarded railroad ties. They were pretty big and he saw no kindling at first—but the train was there still. He ran to the caboose and found the brakeman.

“Well what kindling?” the old man grumbled. “You want to take the roof off my shack. What I’d like to know is what became of that girl? She was a lady—else I don’t know a lady.”

“Where’d you find her?”

“She came down to the yards without any money in St. Louis. Said somebody stole her ticket. I took her in—and I might of lost my job. You seen her?”

“Look, I want to get some kindling.”

“You can take a handful,” the brakeman said tentatively and then repeated, “Where is that girl—off with those rod riders?”

“She’s all right.” Out of his boot he slipped a card.

“If you ever come on a run to Hollywood come to see me.”

The brakeman laughed, and paused:

“Well, anyhow you seem like a nice fellow.”

Taking advantage of his good humor Chris loaded an arm with kindling.

“Don’t worry about that girl,” he said, “I won’t let her get hurt.”

“Say don’t,” the brakeman said at the door. “Don’t. She was like my own daughter. I took her in here, but I didn’t like the looks of that gang. Know? They didn’t look nice. Know? Usually they look not so bad nowadays.”

“Goodbye there.”

—The couplings clanged. Meditatively Chris walked to where he had left her.

“Look!” she exclaimed.

The nineteen wild green eyes of a bus were coming up to them through the dark.

“Wouldn’t it be good?—if we could.”

“We can,” he assured her, “I can take you all the way to Los Angeles—”

She doubted.

“You know sometimes I think you have got a position out there.”

In the bus she asked him:

“Where’d you get the money to do this?”

The dozy passengers moved to give them seats.

“Well I’m making up a picture,” he said.

Still she didn’t know whether to believe him or not, but it was a somewhat weary face for a young man, and must have worked some time.

“What are you writing now?” she asked.

“This. It’s a picture I’ve got in mind. It’s about hoboes—”

“And you’re going to try to sell them the idea out in Hollywood.”

“Sell them! It’s sold. I’m getting data. My name’s Chris Cooper. I wrote Linda Monday.”

She seemed to have become tired and listless.

“I don’t go much to the pictures,” she said, “You’ve been mighty sweet to me.” She gave him a side smile, half of her face, like a small white cliff.

“Damn, you’re beautiful!” he said involuntarily, and then: “Who are you? You’re somebody—” Again he had to lower his voice as a weary pair in front of them stirred.

“I’m the mystery girl,” she said.

“I begin to think you are. You’ve got me guessing.”

The bus slowed for its Dallas station. Midnight was rocking overhead. More than half the passengers disembarked, permanently or temporarily, among them Chris; the girl remained in her chair and, as she rested, a faint glow of pink stole back into her cheeks.

At the telegraph office Chris dispatched a wire to a celebrated woman upon a fine streamlined train westbound.

He returned to the bus and roused the girl from a half sleep to ask casually:

“Did you ever hear of Velia Tolliver?”

“Of course. Who hasn’t? Isn’t she the discovery of the year?”

“She’s on her way to the coast. I wired her to get off at El Paso and I’d join her there.”

But he was tired of showing off for a girl who obviously didn’t believe him; and perhaps the baffled vanity in his eyes gave her the energy to say:

“I don’t care much who you are. You’ve been good to me. You saved my check.” Sleepily she clutched her worn purse containing the much folded check. “That’s what I didn’t want the tramp to get.”

“You certainly seem to think it’s valuable?”

“Well, did you ever hear of Paul Downs?”

“Seems to me I have.”

“He was my father. That’s his signature.” Fatigue overcame her again and without further elucidation she dozed as they got in motion to cross the long Texas night.

The bulbs, save for two, were dimmed to a pale glow; the faces of the passengers as they composed themselves for slumber were almost universally yellow tired.

“Good night,” she murmured.

***

Not till the next day when they paused at Midland for lunch did he say:

“You said your father’s name was Paul Downs. Was he called ‘Popsy’ Downs? And did he own a string of coast-to-coast steamers?”

“That was father.”

“I remember the name now, because he lent us an old eighteen-fifty brig we used in Gold Dust. When I met him he was throwing a nice little party—”

He shut up at the expression on her face.

“We heard about it.”

“Who’s we?”

“Mother and I. We were well off then—when father died, or we thought we were.” She sighed. “Let’s go back to the bus again…”

…It was another fine night when they drew into El Paso.

“You got any money?” he asked.

“Oh, plenty.”

“Liar. Here’s two dollars. You can pay me back some time. Go buy yourself something you need—you know—stockings, handkerchiefs—anything.”

“You sure you can spare it?”

“You still don’t believe me—just because I haven’t got much cash in hand.”

They stood in front of a window filled with open road maps.

“Goodbye then,” she said tentatively, “And thanks.”

Chris felt a pull at his heart. “It’s just au revoir. I’m meeting you at the railroad station in an hour.”

“All right.”

She was gone before he realized it. She was only the back of her hair curling up around her hat.

On the way he thought what the girl would probably do—thought with her. He worried whether she would, after all, return to the station.

He was sure she would walk, walk and look in windows. He knew El Paso and guessing the streets she would travel, he felt more than delight when he found her half an hour before the arrival of the train.

“So you’re going along. Come to the ticket window.”

“I’ve changed my mind. You paid all you should for me.”

His feeling came to words:

“I’d like to pay a lot more mileage for you.”

“Let's forget that. Here’s your two dollars. I haven’t spent any. Oh yes I did. I spent twenty-five, no—I spent thirty-five cents. Here’s the rest. Here!”

“Talk nonsense, will you? Just when I’d begun to think you had some sense. Velia’s train’ll be in in a minute and she’ll be getting off. She’s the prettiest thing I ever saw. She’s our choice for the girl in the hobo picture.”

“Sometimes I almost believe you’re what you say you are.”

Then, as they stood by the news-stand he turned to her once more—to see the snow melting as he looked at her. Her pink lips were scarlet now…

…The train came in. Velia Tolliver, looking exactly like herself, seemed much upset.

“Well, here we are,” she said, “Let’s have a quick one in the buffet, and we can wire Bennie Giskig to meet us in his car at Yuma. I’m tired of trains. Then I want to get back on board and go to bed. Even the porters looked at me as if I had lines on my face.”

She looked curiously at the girl as they came into her drawing room ten minutes later.

“My maid got sick and had to be left in Chicago—and now I’m helpless. What’s your name? I don’t think I caught it.”

“Judith Downs.”

For a moment as Velia flashed a huge blue stone, bigger than an eye, upon them and then put it into a blue sack Judy wondered if she was going to be asked to take the place of the missing maid.

Chris and Judy went down to the observation car and presently Velia came back and joined them, obviously refreshed by a few surreptitious drinks, by way of making up for her maid’s absence, so to speak.

“You’re hopeless, Chris,” she declared. “After you leave me in New York and go off on this crazy trip and what do I get—I get a wire to get off the train and you show up with a girl!”

She wiped away a few vexatious tears and got herself into control.

“All right. Then I’ll accept her—if you don’t love me.” She examined Judy more critically than heretofore. “You’re—pretty dusty. Do you want to borrow some clothes? I got one trunk in my drawing-room. Come on.”

… Ten minutes later Judy Downs said:

“No—just this skirt and this sweater.”

“But that’s just an old sweater. I’m almost sure I gave it to my maid a long time ago, and it just got mixed up in here. You won’t? All right. Go along with Chris and have you a time. I think I’ll just lie down for awhile.”

But Judy had not chosen the sweater because it was old, but because on a tab at the back of the neck she had seen the name “Mabel Dychenik.”

And the check she carried so carefully in her purse read:

Pay to the Order of Mabel Dychenik—$10.00

III

Back in the observation car, feeling fresher, Judy said:

“She was nice lending me this outfit. Who is she?”

“Oh, she began as a rural gold digger; she was just out of the mines when I picked her out of a ten-twenty-thirty. I even changed her name for her.”

They sat late on the observation platform while New Mexico streamed away under the stars; and they had a quick breakfast together in the morning. Velia didn’t appear until they reached Yuma. They all went to the little hotel to spruce up and wait for Bennie Giskig, who had wired that he would meet them there in his own car and carry them the intervening miles to Hollywood.

“Lots of variety in the trip anyhow,” Chris said to Judy, “Easy stages—each one different from the last—it’s been fun—with you.”

“With you too.”

And then suddenly it wasn’t fun when Velia came out of the women’s room wailing:

“I’ve lost my little blue bag I always have on my wrist—I mean what was inside it. My big stone—the only nice thing I have! My blue diamond!”

“Did you look thoroughly? Through all your bags?”

“My things are on the train. But I know it was in its own case and that was on my arm.”

“Suppose it slipped out—“

“It couldn’t,” she insisted. “The case has a patent catch—it couldn’t just open and close again.”

“It must be in your baggage.”

“Oh no!” With sudden suspicion she turned toward Judy, “Where is it? I want it back now!”

“I certainly haven’t got it.”

“Then where is it? I’ll have you searched—”

***

“Be reasonable, Velia,” Chris said.

“But who is she? Who is this girl? We don’t know.”

“At least come in the side parlor here,” he urged.

She was on the edge of collapse.

“I want her searched.”

“I don’t mind,” offered Judy. “I’ve only got the coat and sweater you lent me. I threw away the old dress on the train, it wasn’t worth saving. And I couldn’t very well have swallowed it.”

“You see, she knows, Chris. She knows that thieves swallow the jewels they’ve stolen.”

“Don’t be absurd!” he said.

While the search was being conducted by the telephone girl under Velia’s close supervision, Bennie Giskig, one of the supervisors of Bijou Pictures, drove up at the door. He encountered Chris in the lobby.

“Ah, good,” he said, in the cocksure manner that Chris had come to associate with his metier, a manner sharply different from those who actually wrote and directed the pictures. “Good to see you, Chris. I want to talk to you. That’s why I drove here. I am so busy a man. Where is Velia—I want to see her even more. Can we start right away—I have business back in Hollywood.”

“There’s a little trouble here,” Chris answered. “Bennie, I found a girl for you. She’s with us.”

“All right. I’ll look at her in the car—but we got to get started back.”

“And also I’ve got the story.”

“So.” He hesitated. “Chris, I must tell you frankly plans have changed a little since we started on that. It’s such a sad story,”

“On the contrary, I’ve found it can be a very cheerful story.”

“We can talk about it in the car. Anyhow Velia goes into another production first, right now, almost today—”

At this moment the latter, all upset and tearful and at a loss, came out of the coatroom, followed by Judy.

“Bennie,” she cried, “I’ve lost my big diamond. You’ve seen it.”

“So? That’s too bad. It was insured?”

“Not for anything like its real value. It was a rare stone.”

“We must start now. We can talk it over in the car.”

She consented to be embarked and they set out for the coast up and over a hill and then down into a valley of green morning light with rows of avocado pear trees and late lettuce.

Chris let Bennie unburden himself to Velia about the immediacy of her picture—a matter which in her distraught condition she scarcely understood at all.

Then he said:

“I still think my story’s better than that one, Bennie. I’ve changed it. I’ve learned a lot since I started on this trip. This story is called ‘Travel Together.’ It’s more than just about hoboes now. It’s a love story.”

“I tell you the subject’s too gloomy. People want to laugh now. For instance in this picture for Velia we got a—”

But Chris cut through him impatiently.

“Then I’ve wasted my month—while you’ve changed your mind.”

“Shulkopf couldn’t reach you, could he? We didn’t know where you were. Besides you’re on salary, aren’t you?”

“I like to work for more than salary.”

Bennie touched his knee conciliatingly.

“Forget it. I’ll set you to work on a picture that—”

“But I want to write this picture, while I’m full of it. From New York to Dallas I was on the freights—”

“Who cares about that though? Now wouldn’t you rather ride along a smooth road in a big limousine?”

“I thought so once.”

Bennie turned to Velia as if in good humored despair.

“Velia, he thinks he would like to ride the freights and—”

“Come on, Judy,” Chris said suddenly, “Let’s get out. We can make it on foot.” And then to Bennie, “My contract was up last week anyhow.”

“But we were going to renew—”

“I think I can sell this somewhere else. The whole hobo idea was mine anyhow—so I guess it reverts to me.”

“Sure, sure. We don’t want it. But Chris, I tell you—”

He seemed to realize now he was losing one of his best men, one who had no lack of openings, who would go far in the industry.

But Chris was adamant.

“Come on, Judy. Stop here, driver.”

Absorbed in her loss to the exclusion of all else Velia cried to him: “Chris! If you find out anything about my diamond—if this girl—”

“She hasn’t got it. You know that. Maybe I have.”

“You haven’t.”

“No, I haven’t. Goodbye Velia. Goodbye Bennie, I’ll come up and see you when this play’s a smash. And tell you about it.”

In a few minutes the car was a dot far down the highway.

Chris and Judy sat by the roadside.

“Well.”

“Well.”

“I guess it’s shoe leather and hitch-hike again.”

“I guess so.”

He looked at the delicate white rose of her cheeks and the copper green eyes, greener than the green-brown foliage around them.

“Have you got that diamond?” he asked suddenly.

“No.”

“You’re lying.”

“Well then, yes and no,” she said.

“What did you do with it?”

“Oh, it’s so pleasant here, let’s not talk about it now.”

“Let's not talk about it!” he repeated astonished at her casual attitude—as if it didn’t matter! “I’m going to get that stone back to Velia. I’m responsible. I introduced you, after all—”

“I can’t help you,” she said rather coolly. “I haven’t got it.”

“What did you do with it? Give it to a confederate?”

“Do you think I’m a criminal? And I certainly would have to have been a marvelous plotter. To’ve met you and all.”

“If you are, you’re finished being one from now on. Velia’s going to get her diamond.”

“It happens to be mine.”

“I suppose because possession is nine points of the law—Well—”

“I didn't mean that,” she interrupted with angry tears. “It belongs to my mother and me. Oh, I’ll tell you the whole story though I was saving it. Father owned the Nyask Line and when he was eighty-six and so collapsed we never let him steam around to his west coast office without a doctor and nurse—he broke away one night and gave a diamond worth eighty thousand dollars to a girl in a nightclub. He told the nurse about it because he thought it was gay and clever. And we know what it was worth, because we found the bill from a New York dealer—and it was receipted.

“Father died before he reached New York—and he left absolutely nothing else except debts. He was senile—crazy, you understand. He should have been at home.”

Chris interrupted.

“But how did you know that was Velia’s diamond?”

“I didn’t. I was going West to find a girl named Mabel Dychenik—because we found a check made out to her for ten dollars in his bank returns. And his secretary said he’d never signed a check except the night he ran away from the ship.”

“Still you didn’t know—” He considered. “After you saw the diamond. I suppose they’re pretty rare.”

“Rare! That size? It was described in the jeweller’s invoice with a pedigree like a thoroughbred’s. We thought sure we’d find it in his safe.”

He guessed: “So I suppose you were going to plead with the girl and try to litigate.”

“I was—but when I met a hard specimen like Velia, or Mabel, I knew she’d fight it to the end. And we have no money to go into it. Then, last night, this chance came—and I thought if I had it—”

She broke off and he finished for her:

“—that when she cooled down she might listen to reason.”

Sitting there Chris considered for a long time the rights and wrongs of the thing. From one point of view it was indefensible—yet he had read of divorced couples contending for a child to the point of kidnapping. What was the justice of that—love? But here, on Judy’s part, what had influenced her action was her human claim on the means of her own subsistence.

Something could be done with Velia.

“What did you do with it?” he demanded suddenly.

“It’s in the mails. The porter posted it for me when we stopped in Phoenix this morning—wrapped in my old skirt.”

“My God! You took another awful chance there.”

“All this trip was an awful chance.”

Now, presently, they were on their feet, walking westward with a mild sun arching up behind them.

“Travel Together,” Chris said to himself, abstractedly, “Yes, there’s the title of my script.” And then to her, “And I have title on you to be my girl.”

“I know you have.”

“‘Travel Together’”, he repeated, “I suppose that's one of the best things you can do to find out about another person.”

“We’ll travel a lot, won’t we?”

“Yes, and always together.”

“No. You’ll travel alone sometimes—but I’ll always be there when you come back.”

“You better be.”

Manuscript

Typescript for the short story "Travel Together" n.p, 1935, 22 pages (11 1/8 x 8 1/2 in.; 283 x 216 mm). One pencil correction.

Unpublished Fitzgerald Hollywood short story involving a screenwriter travelling as a hobo who meets an unusual girl on the rails and brings her back to Hollywood. After a starlet's diamond is stolen, it is revealed the pretty tramp is not at all as she at first appeared./p>

Published in I'd Die For You collection.

Not illustrated.