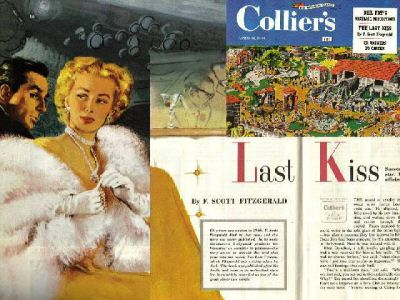

Last Kiss

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The sound of revelry fell sweet upon James Leonard’s ear. He alighted, a little awed by his new limousine, and walked down the red carpet through the crowd. Faces strained forward, weird in the split glare of the drum lights—but after a moment they lost interest in him. Once Jim had been annoyed by his anonymity in Hollywood. Now he was pleased with it.

Elsie Donohue, a tall, lovely, gangling girl had a seat reserved for him at her table. “If I had no chance before,” she said, “what chance have I got now that you’re so important?” She was half teasing—but only half.

“You’re a stubborn man,” she said. “When we first met, you put me in the undesirable class. Why?” She tossed her shoulders despairingly as Jim’s eyes lingered on a little Chinese beauty at the next table. “You’re looking at Ching Loo Poo-poo, Ching Loo Poo-poo! And for five long years I’ve come out to this ghastly town—”

“They couldn’t keep you away,” Jim objected. “It’s on your swing around—the Stork Club, Palm Beach and Dave Chasen’s.”

Tonight something in him wanted to be quiet. Jim was thirty-five and suddenly on the winning side of all this. He was one of those who said how pictures should go, what they should say. It was a fine pure feeling to be on top.

One was very sure that everything was for the best, that the lights shone upon fair ladies and brave men, that pianos dripped the right notes and that the young lips singing them spoke for happy hearts.

They absolutely must be happy, these beautiful faces. Andthen in a twilight rumba, a face passed Jim’s table that was not quite happy. It had gone before Jim formulated this opinion, yet it remained fixed on his memory for some seconds. It was the head of a girl almost as tall as he was, with opaque brown eyes and cheeks as porcelain as those of the little Chinese.

“At least you’re back with the white race,” said Elsie, following his eyes.

Jim wanted to answer sharply: You’ve had your day—three husbands. How about me? Thirty-five and still trying to match every woman with a childhood love who died, still finding fatally in every girl the similarities and not the differences.

The next time the lights were dim he wandered through the tables to the entrance hall. Here and there friends hailed him—more than the usual number of course, because his rise had been in the Reporter that morning, but Jim had made other steps up and he was used to that. It was a charity ball, and by the stairs was the man who imitated wallpaper about to go in and do a number and Bob Bordley with a sandwich board on his back:

At Ten Tonight in the Hollywood Bowl Sonja Henie Will Skate on Hot Soup.

By the bar Jim saw the producer whom he was displacing tomorrow having an unsuspecting drink with the agent who had contrived his ruin. Next to the agent was the girl whose face had seemed sad as she danced by in the rumba.

“Oh, Jim,” said the agent, “Pamela Knighton—your future star.”

She turned to him with professional eagerness. What the agent’s voice had said to her was: “Look alive! This is somebody.”

“Pamela’s joined my stable,” said the agent. “I want her to change her name to Boots.”

“I thought you said Toots,” the girl laughed.

“Toots or Boots. It’s the oo-oo sounds. Cutie shoots Toots. Judge Hoots. No conviction possible. Pamela is English. Her real name is Sybil Higgins.”

II

It seemed to Jim that the deposed producer was looking at him with an infinite something in his eyes—not hatred, not jealousy, but a profound and curious astonishment that asked: Why? Why? For Heaven’s sake, why? More disturbed by this than enmity, Jim surprised himself by asking the English girl to dance. As they faced each other on the floor his exultation of the early evening came back.

“Hollywood’s a good place,” he said, as if to forestall any criticism from her. “You’ll like it. Most English girls do—they don’t expect too much. I’ve had luck working with English girls.”

“Are you a director?”

“I’ve been everything—from press agent on. I’ve just signed a producer’s contract that begins tomorrow.”

“I like it here,” she said after a minute. “You can’t help expecting things. But if they don’t come I could always teach school again.”

Jim leaned back and looked at her—his impression was of pink-and-silver frost. She was so far from a schoolmarm, even a schoolmarm in a Western, that he laughed. But again he saw that there was something sad and a little lost within the triangle formed by lips and eyes.

“Whom are you with tonight?” he asked.

“Joe Becker,” she answered, naming the agent. “Myself and three other girls.”

“Look—I have to go out for half an hour. To see a man—this is not phony. Believe me. Will you come along for company and night air?”

She nodded.

On the way they passed Elsie Donohue, who looked inscrutably at the girl and shook her head slightly at Jim. Out in the clear California night he liked his big car for the first time, liked it better than driving himself. The streets through which they rolled were quiet at this hour. Miss Knighton waited for him to speak.

“What did you teach in school?” he asked.

“Sums. Two and two are four and all that.”

“It’s a long jump from that to Hollywood.”

“It’s a long story.”

“It can’t be very long—you’re about eighteen.”

“Twenty.” Anxiously she asked, “Do you think that’s too old?”

“Lord, no! It’s a beautiful age. I know—I’m twenty-one myself and the arteries haven’t hardened much.”

She looked at him gravely, estimating his age and keeping it to herself.

“I want to hear the long story,” he said.

She sighed. “Well, a lot of old men fell in love with me. Old, old men—I was an old man’s darling.”

“You mean old gaffers of twenty-two?”

“They were between sixty and seventy. This is all true. So I became a gold digger and dug enough money out of them to go to New York. I walked into “21” the first day and Joe Becker saw me.”

“Then you’ve never been in pictures?” he asked.

“Oh, yes—I had a test this morning,” she told him.

Jim smiled. “And you don’t feel bad taking money from all those old men?” he inquired.

“Not really,” she said, matter-of-fact. “They enjoyed giving it to me. Anyhow it wasn’t really money. When they wanted to give me presents I’d send them to a certain jeweler, and afterward I’d take the presents back to the jeweler and get four-fifths of the cash.”

“Why, you little chiseler!”

“Yes,” she admitted. “Somebody told me how. I’m out for all I can get.”

“Didn’t they mind—the old men, I mean—when you didn’t wear their presents?”

“Oh, I’d wear them—once. Old men don’t see very well, or remember. But that’s why I haven’t any jewelry of my own.” She broke off. “This I’m wearing is rented.”

Jim looked at her again and then laughed aloud. “I wouldn’t worry about it. California’s full of old men.”

They had twisted into a residential district. As they turned a corner Jim picked up the speaking tube. “Stop here.” He turned to Pamela, “I have some dirty work to do.”

He looked at his watch, got out and went up the street to a building with the names of several doctors on a sign. He went past the building walking slowly, and presently a man came out of the building and followed him. In the darkness between two lamps Jim went close, handed him an envelope and spoke concisely. The man walked off in the opposite direction and Jim returned to the car.

“I’m having all the old men bumped off,” he explained. “There’re some things worse than death.”

“Oh, I’m not free now,” she assured him. “I’m engaged.”

“Oh.” After a minute he asked, “To an Englishman?”

“Well—naturally. Did you think—“ She stopped herself but too late.

“Are we that uninteresting?” he asked.

“Oh, no.” Her casual tone made it worse. And when she smiled, at the moment when a street light shone in and dressed her beauty up to a white radiance, it was more annoying still.

“Now you tell me something,” she asked. “Tell me the mystery.”

“Just money,” he answered almost absently. “That little Greek doctor keeps telling a certain lady that her appendix is bad—we need her in a picture. So we bought him off. It’s the last time I’ll ever do anyone else’s dirty work.”

She frowned. “Does she really need her appendix out?”

He shrugged. “Probably not. At least that rat wouldn’t know. He’s her brother-in-law and he wants the money.”

After a long time Pamela spoke judicially. “An Englishman wouldn’t do that.”

“Some would,” he said shortly, “—and some Americans wouldn’t.”

“An English gentleman wouldn’t,” she insisted.

“Aren’t you getting off on the wrong foot,” he suggested, “if you’re going to work here?”

“Oh, I like Americans all right—the civilized ones.”

From her look Jim took this to include him, but far from being appeased he had a sense of outrage. “You’re taking chances,” he said. “In fact, I don’t see how you dared come out with me. I might have had feathers under my hat.”

“You didn’t bring a hat,” she said placidly. “Besides, Joe Becker said to. There might be something in it for me.”

After all he was a producer and you didn’t reach eminence by losing your temper—except on purpose. “I’m sure there’s something in it for you,” he said, listening to a stealthily treacherous purr creep into his voice.

“Are you?” she demanded. “Do you think I’ll stand out at all—or am I just one of the thousands?”

“You stand out already,” he continued on the same note. “Everyone at the dance was looking at you.” He wondered if this was even faintly true. Was it only he who had fancied some uniqueness? “You’re a new type,” he went on. “A face like yours might give American pictures a—a more civilized tone.”

This was his arrow—but to his vast surprise it glanced off.

“Oh, do you think so?” she cried. “Are you going to give me a chance?”

“Why, certainly.” It was hard to believe that the irony in his voice was missing its mark. “But after tonight there’ll be so much competition that—”

“Oh, I’d rather work for you,” she declared. “I’ll tell Joe Berker—”

“Don’t tell him anything,” he interrupted.

“Oh, I won’t. I’ll do just as you say,” she promised.

Her eyes were wide and expectant. Disturbed, he felt that words were being put in his mouth or slipping from him unintended. That so much innocence and so much predatory toughness could go side by side behind this gentle English voice.

“You’d be wasted in bits,” he began. “The thing is to get a fat part—” He broke off and started again, “You’ve got such a strong personality that—”

“Oh, don’t!” He saw tears blinking in the comers of her eyes. “Let me just keep this to sleep on tonight. You call in the morning—or when you need me.”

The car came to rest at the carpet strip in front of the dance. Seeing Pamela, the crowd bulged forward grotesquely, autograph books at the ready. Failing to recognize her, it sighed back behind the ropes.

In the ballroom he danced her to Becker’s table.

“I won’t say a word,” she answered. From her evening case she took a card with the name of her hotel penciled on it. “If any other offers come I’ll refuse them.”

“Oh, no,” he said quickly.

“Oh, yes.” She smiled brightly at him and for an instant the feeling Jim had had on seeing her came back. It was an impression of a rich warm sympathy, of youth and suffering side by side. He braced himself for a final quick slash to burst the scarcely created bubble.

“After a year or so—” he began. But the music and her voice overrode him.

“I’ll wait for you to call. You’re the—you’re the most civilized American I’ve ever met.”

She turned her back as if embarrassed by the magnificence of her compliment. Jim started back to his table—then seeing Elsie Donohue talking to a woman across his empty chair, he turned obliquely away. The room, the evening had gone raucous—the blend of music and voices seemed inharmonious and accidental and his eyes covering the room saw only jealousies and hatreds—egos tapping like drumbeats up to a fanfare. He was not above the battle as he had thought.

He started for the coatroom thinking of the note he would dispatch by waiter to his hostess: “You were dancing.” Then he found himself almost upon Pamela Knighton’s table, and turning again he took another route toward the door.

III

A picture executive can do without intelligence but he cannot do without tact. Tact now absorbed Jim Leonard to the exclusion of everything else. Power should have pushed diplomacy into the background, leaving him free, but instead it intensified all his human relations—with the executives, with the directors, writers, actors and technical men assigned to his unit, with department heads, censors and “men from the East” besides. So the stalling off of one lone English girl, with no weapon except the telephone and a little note that reached him from the entrance desk, should have been no problem at all.

Just passing by the studio and thought of you and of our ride. There have been some offers but I keep stalling Joe Becker. If I move I will let you know.

A city full of youth and hope spoke in it—in its two transparent lies, the brave falsity of its tone. It didn’t matter to her—all the money and glory beyond the impregnable walls. She had just been passing by—just passing by.

That was after two weeks. In another week Joe Becker dropped in to see him. “About that little English girl, Pamela Knighton—remember? How’d she strike you?”

“Very nice.”

“For some reason she didn’t want me to talk to you.” Joe looked out the window. “So I suppose you didn’t get along so well that night.”

“Sure we did.”

“The girl’s engaged, you see, to some guy in England.”

“She told me that,” said Jim, annoyed. “I didn’t make any passes at her if that’s what you’re getting at.”

“Don’t worry—I understand those things. I just wanted to tell you something about her.”

“Nobody else interested?”

“She’s only been here a month. Everybody’s got to start. I just want to tell you that when she came into “21” that day the barflies dropped like—like flies. Let me tell you—in one minute she was the talk of cafe society.”

“It must have been great,” Jim said dryly.

“It was. And Lamarr was there that day too. Listen—Pam was all alone, and she had on English Clothes, I guess, nothing you’d look at twice—rabbit fur. But she shone through it like a diamond.”

“Yeah?”

“Strong women,” Joe went on, “wept into their Vichyssoise. Elsa Maxwell—”

“Joe, this is a busy morning.”

“Will you look at her test?”

“Tests are for make-up men,” said Jim, impatiently. “I never believe a good test. And I always suspect a bad one.”

“Got your own ideas, eh?”

“About that,” Jim admitted. “There’ve been a lot of bad guesses in projection rooms.”

“Behind desks, too,” said Joe rising.

IV

A second note came after another week:

When I phoned yesterday one secretary said you were away and one said you were in conference. If this is a run-around tell me. I’m not getting any younger. Twenty-one is staring me in the face—and you must have bumped off all the old men.”

Her face had grown dim now. He remembered the delicate cheeks, the haunted eyes, as from a picture seen a long time ago. It was easy to dictate a letter that told of changed plans, of new casting, of difficulties which made it impossible——

He didn’t feel good about it but at least it was finished business. Having a sandwich in his neighborhood drugstore that night, he looked back at his month’s work as good. He had reeked of tact. His unit functioned smoothly. The shades who controlled his destiny would soon see.

There were only a few people in the drugstore. Pamela Knighton was the girl at the magazine rack. She looked up at him, startled, over a copy of the Illustrated London News.

Knowing of the letter that lay for signature on his desk Jim wished he could pretend not to see her. He turned slightly aside, held his breath, listened. But though she had seen him, nothing happened, and hating his Hollywood cowardice he turned again presently and lifted his hat.

“You’re up late,” he said.

Pamela searched his face momentarily. “I live around the corner,” she said. “I’ve just moved—I wrote you today.”

“I live near here, too.”

She replaced the magazine in the rack. Jim’s tact fled. He felt suddenly old and harassed and asked the wrong question.

“How do things go?” he asked.

“Oh, very well,” she said. “I’m in a play—a real play at the New Faces theater in Pasadena. For the experience.”

“Oh, that’s very wise.”

“We open in two weeks. I was hoping you could come.”

They walked out the door together and stood in the glow of the red neon sign. Across the autumn street newsboys were shouting the result of the night football.

“Which way?” she asked.

The other way from you, he thought, but when she indicated her direction he walked with her. It was months since he had seen Sunset Boulevard, and the mention of Pasadena made him think of when he had first come to California ten years ago, something green and cool.

Pamela stopped before some tiny bungalows around a central court.

“Good night,” she said. “Don’t let it worry you if you can’t help me. Joe has explained how things are, with the war and all. I know you wanted to.”

He nodded solemnly—despising himself.

“Are you married?” she asked.

“No.”

“Then kiss me good night.”

As he hesitated she said. “I like to be kissed good night. I sleep better.”

He put his arms around her shyly and bent down to her lips, just touching them—and thinking hard of the letter on his desk which he couldn’t send now—and liking holding her.

“You see it’s nothing,” she said. “Just friendly. Just good night.”

On his way to the corner Jim said aloud, “Well, I’ll be damned,” and kept repeating the sinister prophecy to himself for some time after he was in bed.

V

On the third night of Pamela’s play Jim went to Pasadena and bought a seat in the last row. A likely crowd was jostling into the theater and he felt glad that she would play to a full house, but at the door he found that it was a revival of Room Service—Pamela’s play was in the Experiment Hall up the stairs.

Meekly he climbed to a tiny auditorium and was the first arrival except for fluttering ushers and voices chattering amid the hammers backstage. He considered a discreet retirement but was reassured by the arrival of a group of five, among them Joe Becker’s chief assistant. The lights went out; a gong was beaten; to an audience of six the play began.

It was about some Mexicans who were being deprived of relief. Concepcione (Pamela Knighton) was having a child by an oil magnate. In the old Horatio Alger tradition, Pedro was reading Marx so someday he could be a bureaucrat and have offices at Palm Springs.

Pedro: “We stay here. Better Boss Ford than Renegade Trotsky.”

Concepcione: (Miss Knighton): “But who will live to inherit?”

Pedro: “Perhaps the great-grandchildren, or the grandchildren of the great-grandchildren. Quien sabe?”

Through the gloomy charade Jim watched Pamela; in front of him the party of five leaned together and whispered after her scenes. Was she good? Jim had no notion—he should have taken someone along, or brought in his chauffeur. What with pictures drawing upon half the world for talent there was scarcely such a phenomenon as a “natural”. There were only possibilities—and luck. He was luck. He was maybe this girl’s luck—if he felt that her pull at his insides was universal.

Stars were no longer created by one man’s casual desire as in the silent days, but stock girls were, tests were, chances were. When the curtain finally dropped, domestically as a Venetian blind, he went backstage by the simple process of walking through a door on the side. She was waiting for him.

“I was hoping you wouldn’t come tonight,” she said. “We’ve flopped. But the first night it was full and I looked for you.”

“You were fine,” he said stiffly.

“Oh, no. You should have seen me then.”

“I saw enough,” he said suddenly. “I can give you a little part. Will you come to the studio tomorrow?”

He watched her expression. Once more it surprised him. Out of her eyes, out of the curve of her mouth gleamed a sudden and overwhelming pity.

“Oh,” she said. “Oh, I’m terribly sorry. Joe brought some people over and next day I signed up with Bernie Wise.”

“You did?”

“I knew you wanted me and at first I didn’t realize you were just a sort of supervisor. I thought you had more power—you know?” She could not have chosen sharper words out of deliberate mischief. “Oh, I like you better personally,” she assured him. “You’re much more civilized than Bernie Wise.”

All right then he was civilized. He could at least pull out gracefully. “Can I drive you back to Hollywood?”

They rode through an October night soft as April. When they crossed a bridge, its walls topped with wire screens, he gestured toward it and she nodded.

“I know what it is,” she said. “But how stupid! English people don’t commit suicide when they don’t get what they want.”

“I know. They come to America.”

She laughed and looked at him appraisingly. Oh, she could do something with him all right. She let her hand rest upon his.

“Kiss tonight?” he suggested after a while.

Pamela glanced at the chauffeur insulated in his compartment. “Kiss tonight,” she said…

He flew East next day, looking for a young actress just like Pamela Knighton. He looked so hard that any eyes with an aspect of lovely melancholy, any bright English voice, predisposed him; he wandered as far afield as a stock company in Erie and a student play at Wellesley—it came to seem a desperate matter that he should find someone exactly like this girl. Then when a telegram called him impatiently back to Hollywood, he found Pamela dumped in his lap.

“You got a second chance, Jim,” said Joe Becker. “Don’t miss it again.”

“What was the matter over there?”

“They had no part for her. They’re in a mess—change of management. So we tore up the contract.”

Mike Harris, the studio head, investigated the matter. Why was Bernie Wise, a shrewd picture man, willing to let her go?

“Bernie says she can’t act,” he reported to Jim. “And what’s more she makes trouble. I keep thinking of Simone and those two Austrian girls.”

“I’ve seen her act,” insisted Jim. “And I’ve got a place for her. I don’t even want to build her up yet. I want to spot her in this little part and let you see.”

VI

A week later Jim pushed open the padded door of Stage III and walked in. Extras in dress clothes turned toward him in the semidarkness; eyes widened.

“Where’s Bob Griffin?”

“In that bungalow with Miss Knighton.”

They were sitting side by side on a couch in the glare of the make-up light, and from the resistance in Pamela’s face Jim knew the trouble was serious.

“It’s nothing,” Bob insisted heartily. “We get along like a couple of kittens, don’t we, Pam? Sometimes I roll over her but she doesn’t mind.”

“You smell of onions,” said Pamela.

Griffin tried again. “There’s an English way and an American way. We’re looking for the happy mean—that’s all.”

“There’s a nice way and a silly way,” Pamela said shortly. “I don’t want to begin by looking like a fool.”

“Leave us alone, will you, Bob?” Jim said.

“Sure. All the time in the world.”

Jim had not seen her in this busy week of tests and fittings and rehearsals, and he thought now how little he knew about her and she of them.

“Bob seems to be in your hair,” he said.

“He wants me to say things no sane person would say.”

“All right — maybe so,” he agreed. “Pamela, since you’ve been working here have you ever blown up in your lines?”

“Why—everybody does sometimes.”

“Listen, Pamela—Bob Griffin gets almost ten times as much money as you do—for a particular reason. Not because he’s the most brilliant director in Hollywood—he isn’t—but because he never blows up in his lines.”

“He’s not an actor,” she said, puzzled.

“I mean his lines in real life. I picked him for this picture because once in a while I blow up. But not Bob. He signed a contract for an unholy amount of money—which he doesn’t deserve, which nobody deserves. But smoothness is the fourth dimension of this business and Bob has forgotten the word "I". People of three times his talent—producers and troupers and directors—go down the sink because they can’t forget it.”

“I know I’m being lectured to,” she said uncertainly. “But I don’t seem to understand. An actress has her own—personality—”

He nodded. “And we pay her five times what she could get for it anywhere else—if she’ll only keep it off the floor where it trips the rest of us up. You’re tripping us all up, Pamela.”

I thought you were my friend, her eyes said.

He talked to her a few minutes more. Everything he said he believed with all his heart, but because he had twice kissed those lips, he saw that it was support and protection they wanted from him. All he had done was to make her a little shocked that he was not on her side. Feeling rather baffled and sorry for her loneliness he went to the door of the bungalow and called: “Hey, Bob!”

Jim went about other business. He got back to his office to find Mike Harris waiting.

“Again that girl’s making trouble.”

“I’ve been over there.”

“I mean in the last five minutes!” cried Harris. “Since you left she’s made trouble! Bob Griffin had to stop shooting for the day. He’s on his way over.”

Bob came in. “There’s one type you can’t seem to get at—can’t find what makes them that way. I’m afraid it’s either Pamela or me.”

There was a moment’s silence. Mike Harris, upset by the whole situation, suspected that Jim was having an affair with the girl.

“Give me till tomorrow morning,” said Jim. “I think I can find what’s back of this.”

Griffin hesitated but there was a personal appeal in Jim’s eyes—an appeal to associations of a decade. “All right, Jim,” he agreed.

When they had gone Jim called Pamela’s number. What he had almost expected happened, but his heart sank none the less when a man’s voice answered the phone...

Excepting a trained nurse, an actress is the easiest prey for the unscrupulous male. Jim had learned that in the background of their troubles or their failures there was often some plausible confidence man, some soured musician, who asserted his masculinity by way of interference, midnight nagging, bad advice. The technique of the man was to belittle the woman’s job and to question endlessly the motives and intelligence of those for whom she worked.

Jim was thinking of all this when he reached the bungalow hotel in Beverly Hills where Pamela had moved. It was after six. In the court a cold fountain splashed senselessly against the December fog and he heard Major Bowes’s voice loud from three radios.

When the door of the apartment opened Jim stared. The man was old—a bent and withered Englishman with ruddy winter color dying in his face. He wore an old dressing gown and slippers and he asked Jim to sit down with an air of being at home. Pamela would be in shortly.

“Are you a relative?” Jim asked wonderingly.

“No, Pamela and I met here in Hollywood. We were strangers in a strange land. Are you employed in pictures, Mr—Mr——”

“Leonard,” said Jim. “Yes. At present I’m Pamela’s boss.”

A change came into the man’s eyes—the watery blink became conspicuous, there was a stiffening of the old lids. The lips curled down and backward and Jim was gazing into an expression of utter malignancy. Then the features became old and bland again.

“I hope Pamela is being handled properly?”

“You’ve been in pictures?” Jim asked.

“Till my health broke down. But I am still on the rolls at Central Casting and I know everything about this business and the souls of those who own it—” He broke off.

VII

The door opened and Pamela came in. “Well, hello.” she said in surprise. “You’ve met? The Honorable Chauncey Ward—Mr. Leonard.”

Her glowing beauty, borne in from outside like something snatched from wind and weather, made Jim breathless for a moment.

“I thought you told me my sins this afternoon,” she said with a touch of defiance.

“I wanted to talk to you away from the studio.”

“Don’t accept a salary cut,” the old man said. “That’s an old trick.”

“It’s not that, Mr. Ward,” said Pamela. “Mr. Leonard has been my friend up to now. But today the director tried to make a fool of me, and Mr. Leonard backed him up.”

“They all hang together,” said Mr. Ward.

“I wonder—” began Jim. “Could I possibly talk to you alone?”

“I trust Mr. Ward,” said Pamela frowning. “He’s been over here twenty-five years and he’s practically my business manager.”

Jim wondered from what deep loneliness this relationship had sprung. “I hear there was more trouble on the set,” he said.

“Trouble!” She was wide-eyed. “Griffin’s assistant swore at me and I heard it. So I walked out. And if Griffin sent apologies by you I don’t want them—our relation is going to be strictly business from now on.”

“He didn’t send apologies,” said Jim uncomfortably. “He sent an ultimatum.”

“An ultimatum!” she exclaimed. “I’ve got a contract, and you’re his boss, aren’t you?”

“To an extent,” said Jim, “—but, of course, making pictures is a joint matter—”

“Then let me try another director.”

“Fight for your rights,” said Mr. Ward. “That’s the only thing that impresses them.”

“You’re doing your best to wreck this girl,” said Jim quietly.

“You can’t frighten me,” snapped Ward. “I’ve seen your type before.”

Jim looked again at Pamela. There was exactly nothing he could do. Had they been in love, had it ever seemed the time to encourage the spark between them, he might have reached her now. But it was too late. In the Hollywood darkness outside he seemed to feel the swift wheels of the industry turning. He knew that when the studio opened tomorrow, Mike Harris would have new plans that did not include Pamela at all.

VIII

For a moment longer he hesitated. He was a well-liked man, still young, and with a wide approval. He could buck them about this girl, send her to a dramatic teacher. He could not bear to see her make such a mistake. On the other hand he was afraid that somewhere people had yielded to her too much, spoiled her for this sort of career.

“Hollywood isn’t a very civilized place,” said Pamela.

“It’s a jungle,” agreed Mr. Ward. “Full of prowling beasts of prey.”

Jim rose. “Well, this one will prowl out,” he said. “Pam, I’m very sorry. Feeling like you do, I think you’d be wise to go back to England and get married.”

For a moment a flicker of doubt was in her eyes. But her confidence, her young egotism, was greater than her judgement—she did not realize that this very minute was opportunity and she was losing it forever.

For she had lost it when Jim turned and went out. It was weeks before she knew how it happened. She received her salary for some months—Jim saw to that—but she did not set foot on that lot again. Nor on any other. She was placed quietly on that black list that is not written down but that functions at backgammon games after dinner, or on the way to the races. Men of influence stared at her with interest at restaurants here and there but all their inquiries about her reached the same dead end.

She never gave up during the following months—even long after Becker had lost interest and she was in want, and no longer seen in the places where people go to be looked at. It was not from grief or discouragement but only through commonplace circumstances that in June she died...

When Jim heard about it, it seemed incredible and terrible. He learned accidentally that she was in the hospital with pneumonia—he telephoned and found that she was dead. “Sybil Higgins, actress, English. Age twenty-one.”

She had given old Ward as the person to be informed and Jim managed to get him enough money to cover the funeral expenses, on the pretext that some old salary was still owing. Afraid that Ward might guess the source of the money he did not go to the funeral but a week later he drove out to the grave.

It was a long bright June day and he stayed there an hour. All over the city there were young people just breathing and being happy and it seemed senseless that the little English girl was not one of them. He kept on trying and trying to twist things about so that they would come out right for her but it was too late. He said good-by aloud and promised that he would come again.

Back at the studio he reserved a projection room and asked for her tests and for the bits of film that had been shot on her picture. He sat in a big leather chair in the darkness and pressed the button for it to begin.

In the test Pamela was dressed as he had seen her that first night at the dance. She looked very happy and he was glad she had had at least that much happiness. The reel of takes from the picture began and ran jerkily with the sound of Bob Griffin’s voice off scene and with prop boys showing the number of blocks for the scenes. Then Jim started as the next to the last one came up, and he saw her turn from the camera and whisper: “I’d rather die than do it that way.”

Jim got up and went back to his office where he opened the three notes he had from her and read them again.

“—just passing by the studio and thought of you and of our ride.”

Just passing by. During the spring she had called him twice on the phone, he knew, and he wanted to see her. But he could do nothing for her and could not bear to tell her so.

“I am not very brave,” Jim said to himself. Even now there was fear in his heart that this would haunt him like that memory of his youth, and he did not want to be unhappy.

Several days later he worked late in the dubbing room, and afterward he dropped into his neighborhood drugstore for a sandwich. It was a warm night and there were many young people at the soda counter. He was paying his check when he became aware that a figure was standing by the magazine rack looking at him over the edge of a magazine. He stopped—he did not want to turn for a closer look only to find the resemblance at an end. Nor did he want to go away.

He heard the sound of a page turning and then out of the corner of his eye he saw the magazine cover, the Illustrated London News.

IX

He felt no fear—he was thinking too quickly, too desperately. If this were real and he could snatch her back, start from there, from that night.

“Your change, Mr. Leonard.”

“Thank you.”

Still without looking he started for the door and then he heard the magazine close, drop to a pile and he heard someone breathe close to his side. Newsboys were calling an extra across the street and after a moment he turned the wrong way, her way, and he heard her following—so plain that he slowed his pace with the sense that she had trouble keeping up with him.

In front of the apartment court he took her in his arms and drew her radiant beauty close.

“Kiss me good night,” she said. “I like to be kissed good night. I sleep better.”

Then sleep, he thought, as he turned away—sleep. I couldn’t fix it. I tried to fix it. When you brought your beauty here I didn’t want to throw it away, but I did somehow. There is nothing left for you now but sleep.

Published in Collier's magazine (16 April 1949).

Illustrations by Ward Brackett.