Director's Special [Discard]

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The man and the boy talked intermittently as they drove down Ventura Boulevard in the cool of the morning. The boy, George Baker, was dressed in the austere gray of a military school.

“This is very nice of you, Mr. Jerome.”

“Not at all. Glad I happened by. I have to pass your school going to the studio every morning.”

“What a school!” George volunteered emphatically. “All I do is teach peewees the drill I learned last year. Anyhow I wouldn't go to any war—unless it was in the Sahara or Morocco or the Afghan post.”

James Jerome, who was casting a difficult part in his mind, answered with “Hm!” Then, feeling inadequate, he added:

“But you told me you're learning math—and French.”

“What good is French?”

“What good—say, I wouldn't take anything for the French I learned in the war and just after.”

That was a long speech for Jerome; he did not guess that presently he would make a longer one.

“That's just it,” George said eagerly. “When you were young it was the war, but now it's pictures. I could be getting a start in pictures, but Dolly is narrow-minded.” Hastily he added, “I know you like her; I know everybody does, and I'm lucky to be her nephew, but—” he resumed his brooding, “but I'm sixteen and if I was in pictures I could go around more like Mickey Rooney and the Dead-Ends—or even Freddie Bartholomew.”

“You mean act in pictures?”

George laughed modestly.

“Not with these ears; but there's a lot of other angles. You're a director; you know. And Dolly could get me a start.”

The mountains were clear as bells when they twisted west into the traffic of Studio City.

“Dolly's been wonderful,” conceded George, “but gee whizz, she's arrived. She's got everything—the best house in the valley, and the Academy Award, and being a countess if she wanted to call herself by it. I can't imagine why she wants to go on the stage, but if she does I'd like to get started while she's still here. She needn't be small about that.”

“There's nothing small about your aunt—except her person,” said Jim Jerome grimly. “She's a ‘grande cliente.’ ”

“A what?”

“Thought you studied French.”

“We didn't have that.”

“Look it up,” said Jerome briefly. He was used to an hour of quiet before getting to the studio—even with a nephew of Dolly Bordon. They turned into Hollywood, crossed Sunset Boulevard.

“How do you say that?” George asked.

“ ‘Une grande cliente,’ ” Jerome repeated. “It's hard to translate exactly but I'm sure your aunt was just that even before she became famous.”

George repeated the French words aloud.

“There aren't very many of them,” Jerome said. “The term's misused even in France; on the other hand it is something to be.”

Following Cahuenga, they approached George's school. As Jerome heard the boy murmur the words to himself once more he looked at his watch and stopped the car.

“Both of us are a few minutes early,” he said. “Just so the words won't haunt you, I'll give you an example. Suppose you run up a big bill at a store, and pay it; you become a ‘grand client.’ But it's more than just a commercial phrase. Once, years ago, I was at a table with some people in the Summer Casino at Cannes, in France. I happened to look at the crowd trying to get tables, and there was Irving Berlin with his wife. You've seen him—”

“Oh, sure, I've met him,” said George.

“Well, you know he's not the conspicuous type. And he was getting no attention whatever and even being told to stand aside.”

“Why didn't he tell who he was?” demanded George.

“Not Irving Berlin. Well, I got a waiter, and he didn't recognize the name; nothing was done and other people who came later were getting tables. And suddenly a Russian in our party grabbed the head waiter as he went by and said ‘Listen!’—and pointed: ‘Listen! Seat that man immediately. Il est un grand client—vous comprenez?—un grand client!’”

“Did he get a seat?” asked George.

The car started moving again; Jerome stretched out his legs as he drove, and nodded.

“I'd just have busted right in,” said George. “Just grabbed a table.”

“That's one way. But it may be better to be like Irving Berlin—and your Aunt Dolly. Here's the school.”

“This certainly was nice of you, Mr. Jerome—and I'll look up those words.”

That night George tried them on the young leading woman he sat next to at his aunt's table. Most of the time she talked to the actor on the other side, but George managed it finally.

“My aunt,” he remarked, “is a typical ‘grande cliente.’”

“I can't speak French,” Phyllis said. “I took Spanish.”

“I take French.”

“I took Spanish.”

The conversation anchored there a moment. Phyllis Burns was twenty-one, four years younger than Dolly—and to his nervous system the oomphiest personality on the screen.

“What does it mean?” she inquired.

“It isn't because she has everything,” he said, “the Academy Award and this house and being Countess de Lanclerc and all that…”

“I think that's quite a bit,” laughed Phyllis. “Goodness, I wish I had it. I know and admire your aunt more than anybody I know.”

Two hours later, down by the great pool that changed colors with the fickle lights, George had his great break. His Aunt Dolly took him aside.

“You did get your driver's license, George?”

“Of course.”

“Well, I'm glad, because you can be the greatest help. When things break up will you drive Phyllis Burns home?”

“Sure I will, Dolly.”

“Slowly, I mean. I mean she wouldn't be a bit impressed if you stepped on it. Besides I happen to be fond of her.”

There were men around her suddenly—her husband, Count Hennen de Lanclerc, and several others who loved her tenderly, hopelessly—and as George backed away, glowing, one of the lights playing delicately on her made him stand still, almost shocked. For almost the first time he saw her not as Aunt Dolly, whom he had always known as generous and kind, but as a tongue of fire, so vivid in the night, so fearless and stabbing sharp—so apt at spreading an infection of whatever she laughed at or grieved over, loved or despised—that he understood why the world forgave her for not being a really great beauty.

“I haven't signed anything,” she said explaining, “—East or West. But out here I'm in a mist at present. If I were only sure they were going to make Sense and Sensibility, and meant it for me. In New York I know at least what play I'll do—and I know it will be fun.”

Later, in the car with Phyllis, George started to tell her about Dolly—but Phyllis anticipated him, surprisingly going back to what they had talked of at dinner.

“What was that about a cliente?”

A miracle—her hand touched his shoulder, or was it the dew falling early?

“When we get to my house I'll make you a special drink for taking me home.”

“I don't exactly drink as yet,” he said.

“You've never answered my question.” Phyllis' hand was still on his shoulder. “Is Dolly dissatisfied with who she's—with what she's got?”

Then it happened—one of those four-second earthquakes, afterward reported to have occurred “within a twenty-mile radius of this station.” The instruments on the dashboard trembled; another car coming in their direction wavered and shimmied, side-swiped the rear fender of George's car, passed on nameless into the night, leaving them unharmed but shaken.

When George stopped the car they both looked to see if Phyllis was damaged; only then George gasped: “It was the earthquake!”

“I suppose it was the earthquake,” said Phyllis evenly. “Will the car still run?”

“Oh, yes.” And he repeated hoarsely, “It was the earthquake—I held the road all right.”

“Let's not discuss it,” Phyllis interrupted. “I've got to be on the lot at eight and I want to sleep. What were we talking about?”

“That earth—” He controlled himself as they drove off, and tried to remember what he had said about Dolly. “She's just worried about whether they are going to do Sense and Sensibility. If they're not she'll close the house and sign up for some play—”

“I could have told her about that,” said Phyllis. “They're probably not doing it—and if they do, Bette Davis has a signed contract.”

Recovering his self-respect about the earthquake, George returned to his obsession of the day.

“She'd be a ‘grande cliente,’ ” he said, “even if she went on the stage.”

“Well, I don't know the role,” said Phyllis, “but she'd be unwise to go on the stage, and you can tell her that for me.”

George was tired of discussing Dolly; things had been so amazingly pleasant just ten minutes before. Already they were on Phyllis' street.

“I would like that drink,” he remarked with a deprecatory little laugh. “I've had a glass of beer a couple of times and after that earthquake—well, I've got to be at school at half past eight in the morning.”

When they stopped in front of her house there was a smile with all heaven in it—but she shook her head.

“Afraid the earthquake came between us,” she said gently. “I want to hide my head right under a big pillow.”

George drove several blocks and parked at a corner where two mysterious men swung a huge drum light in pointless arcs over paradise. It was not Dolly who “had everything”—it was Phyllis. Dolly was made, her private life arranged. Phyllis, on the contrary, had everything to look forward to—the whole world that in some obscure way was represented more by the drum light and the red and white gleams of neon signs on cocktail bars than by the changing colors of Dolly's pool. He knew how the latter worked—why, he had seen it installed in broad daylight. But he did not know how the world worked and he felt that Phyllis lived in the same delicious oblivion.

II

After that fall, things were different. George stayed on at school, but this time as a boarder, and visited Dolly in New York on Christmas and Easter. The following summer she came back to the Coast and opened up the house for a month's rest, but she was committed to another season in the East and George went back with her to attend a tutoring school for Yale.

Sense and Sensibility was made after all, but with Phyllis, not Bette Davis, in the part of Marianne. George saw Phyllis only once during that year—when Jim Jerome, who sometimes took him to his ranch for week-ends, told him one Sunday they'd do anything George wanted. George suggested a call on Phyllis.

“Do you remember when you told me about ‘une grande cliente?’”

“You mean I said that about Phyllis?”

“No, about Dolly.”

Phyllis was no fun that day, surrounded and engulfed by men; after his departure for the East, George found other girls and was a personage for having known Phyllis and for what was, in his honest recollection, a superflirtation.

The next June, after examinations, Dolly came down to the liner to see Hennen and George off to Europe; she was coming herself when the show closed—and by transatlantic plane.

“I'd like to wait and do that with you,” George offered.

“You're eighteen—you have a long and questionable life before you.”

“You're just twenty-seven.”

“You've got to stick to the boys you're traveling with.”

Hennen was going first-class; George was going tourist. At the tourist gangplank there were so many girls from Bryn Mawr and Smith and the finishing schools that Dolly warned him.

“Don't sit up all night drinking beer with them. And if the pressure gets too bad slip over into first-class, and let Hennen calm you.”

Hennen was very calm and depressed about the parting.

“I shall go down to tourist,” he said desperately. “And meet those beautiful girls.”

“It would make you a heavy,” she warned him, “like Ivan Lebedeff in a picture.”

Hennen and George talked between upper and lower deck as the ship steamed through the narrows.

“I feel great contempt for you down in the slums,” said Hennen. “I hope no one sees me speaking to you.”

“This is the cream of the passenger list. They call us tycoon-skins. Speaking of furs, are you going after one of those barges in a mink coat?”

“No—I still expect Dolly to turn up in my stateroom. And, actually, I have cabled her not to cross by plane.”

“She'll do what she likes.”

“Will you come up and dine with me tonight—after washing your ears?”

There was only one girl of George's tone of voice on the boat and someone wolfed her away—so he wished Hennen would invite him up to dinner every night, but after the first time it was only for luncheon and Hennen mooned and moped.

“I go to my cabin every night at six,” he said, “and have dinner in bed. I cable Dolly and I think her press agent answers.”

The day before arriving at Southampton, the girl whom George liked quarreled with her admirer over the length of her fingernails or the Munich pact or both—and George stepped out, once more, into tourist class society.

He began, as was fitting, with the ironic touch.

“You and Princeton amused yourself pretty well,” he remarked. “Now you come back to me.”

“It was this way,” explained Martha. “I thought you were conceited about your aunt being Dolly Bordon and having lived in Hollywood—”

“Where did you two disappear to?” he interrupted. “It was a great act while it lasted.”

“Nothing to it,” Martha said briskly. “And if you're going to be like that—”

Resigning himself to the past, George was presently rewarded.

“As a matter of fact I'll show you,” she said. “We'll do what we used to do—before he criticized me as an ignoramus. Good gracious! As if going to Princeton meant anything! My own father went there!”

George followed her, rather excited, through an iron door marked “Private,” upstairs, along a corridor, and up to another door that said “First-Class Passengers Only.”

He was disappointed.

“Is this all? I've been up in first-class before.”

“Wait!”

She opened the door cautiously, and they rounded a lifeboat overlooking a fenced-in square of deck.

There was nothing to see—the flash of an officer's face glancing seaward over a still higher deck, another mink coat in a deck chair; he even peered into the lifeboat to see if they had discovered a stowaway.

“And I found out things that are going to help me later,” Martha muttered as if to herself. “How they work it—if I ever go in for it I'll certainly know the technique.”

“Of what?”

“Look at the deck chair, stupe.”

Even as George gazed, a long-remembered face emerged in its individuality from behind the huge dark of the figure in the mink coat. And at the moment he recognized Phyllis Burns he saw that Hennen was sitting beside her.

“Watch how she works,” Martha murmured. “Even if you can't hear you'll realize you're looking at a preview.”

George had not been seasick so far, but now only the fear of being seen made him control his impulse as Hennen shifted from his chair to the foot of hers and took her hand. After a moment, Phyllis leaned forward, touching his arm gently in exactly the way George remembered; in her eyes was an ineffable sympathy.

From somewhere the mess call shrilled from a bugle—George seized Martha's hand and pulled her back along the way they had come.

“But they like it!” Martha protested. “She lives in the public eye. I'd like to cable Winchell right away.”

All George heard was the word “cable.” Within half an hour he had written in an indecipherable code:

HE DIDN'T COME DOWN TOURIST AS DIDN'T NEED TO BECAUSE SENSE AND SENSIBILITY STOP ADVISE SAIL IMMEDIATELY

GEORGE (COLLECT)

Either Dolly didn't understand or just waited for the clipper anyhow, while George bicycled uneasily through Belgium, timing his arrival in Paris to coincide with hers. She must have been forewarned by his letter, but there was nothing to prove it, as she and Hennen and George rode from Le Bourget into Paris. It was the next morning before the cat jumped nimbly out of the bag, and it had become a sizable cat by afternoon when George walked into the situation. To get there he had to pass a stringy crowd extending from one hotel to another, for word had drifted about that two big stars were in the neighborhood.

“Come in, George,” Dolly called. “You know Phyllis—she's just leaving for Aix-les-Bains. She's lucky—either Hennen or I will have to take up residence, depending on who's going to sue whom. I suggest Hennen sues me—on the charge I made him a poodle dog.”

She was in a reckless mood, for there were secretaries within hearing—and press agents outside and waiters who dashed in from time to time. Phyllis was very composed behind the attitude of “please leave me out of it.” George was damp, bewildered, sad.

“Shall I be difficult, George?” Dolly asked him. “Or shall I play it like a character part—just suited to my sweet nature. Or shall I be primitive? Jim Jerome or Frank Capra could tell me. Have you got good judgment, George, or don't they teach that till college?”

“Frankly—” said Phyllis getting up, “frankly, it's as much a surprise to me as it is to you. I didn't know Hennen would be on the boat any more than he did me.”

At least George had learned at tutoring school how to be rude. He made noxious sounds—and faced Hennen who got to his feet.

“Don't irritate me!” George was trembling a little with anger. “You've always been nice till now but you're twice my age and I don't want to tear you in two.”

Dolly sat him down; Phyllis went out and they heard her emphatic “Not now! Not now!” echo in the corridor.

“You and I could take a trip somewhere,” said Hennen unhappily.

Dolly shook her head.

“I know about those solutions. I've been confidential friend in some of these things. You go away and take it with you. Silence falls— nobody has any lines. Silence—trying to guess behind the silence— then imitating how it was—and more silence—and great wrinkles in the heart.”

“I can only say I am very sorry,” said Hennen.

“Don't be. I'll go along on George's bicycle trip if he'll have me. And you take your new chippie up to Pont-a-Dieu to meet your family. I'm alive, Hennen—though I admit I'm not enjoying it. Evidently you've been dead some time and I didn't know it.”

She told George afterward that she was grateful to Hennen for not appealing to the maternal instinct. She had done all her violent suffering on the plane, in an economical way she had. Even being a saint requires a certain power of organization, and Dolly was pretty near to a saint to those close to her—even to the occasional loss of temper.

But all the next two months George never saw Dolly's eyes gleam silvery blue in the morning; and often, when his hotel room was near hers, he would lie awake and listen while she moved about whimpering softly in the night.

But by breakfast time she was always a “grande cliente.” George knew exactly what that meant now.

In September, Dolly, her secretary and her maid, and George moved into a bungalow of a Beverly Hills hotel—a bungalow crowded with flowers that went to the hospitals almost as fast as they came in. Around them again was the twilight privacy of pictures against a jealous and intrusive world; inside, the telephones, agent, producers, and friends.

Dolly went about, talking possibilities, turning down offers, encouraging others—considered, or pretended to consider, a return to the stage.

“You darling! Everybody's so glad you're back.”

She gave them background; for their own dignity they wanted her in pictures again. There was scarcely any other actress of whom that could have been said.

“Now, I've got to give a party,” she told George.

“But you have. Your being anywhere makes it a party.”

George was growing up—entering Yale in a week. But he meant it too.

“Either very small or very large,” she pondered, “—or else I'll hurt people's feelings. And this is not the time, at the very start of a career.”

“You ought to worry, with people breaking veins to get you.”

She hesitated—then brought him a two-page list.

“Here are the broken veins,” she said. “Notice that there's something the matter with every offer—a condition or a catch. Look at this character part; a fascinating older woman—and me not thirty. It's either money—lots of money tied to a fatal part, or else a nice part with no money. I'll open up the house.”

With her entourage and some scrubbers, Dolly went out next day and made ready as much of the house as she would need.

“Candles everywhere,” George exclaimed, the afternoon of the event. “A fortune in candles.”

“Aren't they nice! And once I was ungrateful when people gave them to me.”

“It's magnificent. I'm going into the garden and rehearse the pool lights—for old times' sake.”

“They don't work,” said Dolly cheerfully. “No electricity works—a flood got in the cellar.”

“Get it fixed.”

“Oh, no—I'm dead broke. Oh yes—I am. The banks are positive. And the house is thoroughly mortgaged and I'm trying to sell it.”

He sat in a dusty chair.

“But how?”

“Well—it began when I promised the cast to go on tour, and it turned hot. Then the treasurer ran away to Canada. George, we have guests coming in two hours. Can't you put candles around the pool?”

“Nobody sent you pool-candlesticks. How about calling in the money you've loaned people?”

“What? A little glamor girl like me! Besides, now they're poorer still, probably. Besides, Hennen kept the accounts except he never put things down. If you look so blue I'll go over you with this dustcloth. Your tuition is paid for a year—”

“You think I'd go?”

Through the big room a man George had never seen was advancing toward them.

“I didn't see any lights, Miss Bordon. I didn't dream you were here, I'm from Ridgeway Real Estate—”

He broke off in profound embarrassment. It was unnecessary to explain that he had brought a client—for the client stood directly behind him.

“Oh,” said Dolly. She looked at Phyllis, smiled—then she sat down on the sofa, laughing. “You're the client; you want my house, do you?”

“Frankly, I heard you wanted to sell it,” said Phyllis.

Dolly's answer was muffled in laughter but George thought he heard: “It would save time if I just sent you all my pawn checks.”

“What's so very funny?” Phyllis inquired.

“Will your—family move in too? Excuse me; that's not my business.” Dolly turned to Ridgeway Real Estate. “Show the Countess around—here's a candlestick. The lights are out of commission.”

“I know the house,” said Phyllis. “I only wanted to get a general impression.”

“Everything goes with it,” said Dolly, adding irresistibly, “—as you know. Except George. I want to keep George.”

“I own the mortgage,” said Phyllis absently.

George had an impulse to walk her from the room by the seat of her sea-green slacks.

“Now Phylis!” Dolly reproved her gently. “You know you can't use that without a riding crop and a black moustache. You have to get a Guild permit. Your proper line is ‘I don't have to listen to this.’ ”

“Well, I don't have to listen to this,” said Phyllis.

When she had gone, Dolly said, “They asked me to play heavies.”

“Why, four years ago,” began George, “Phyllis was—”

“Shut up, George. This is Hollywood and you play by the rules. There'll be people coming here tonight who've committed first degree murder.”

When they came, she was her charming self, and she made everyone kind and charming so that George even failed to identify the killers. Only in a washroom did he hear a whisper of conversation that told him all was guessed at about her hard times. The surface, though, was unbroken. Even Hymie Fink roamed around the rooms, the white blink of his camera when he pointed it, or his alternate grin when he passed by, dividing those who were up from those coming down.

He pointed it at Dolly, on the porch. She was an old friend and he took her from all angles. Judging by the man she was sitting beside, it wouldn't be long now before she was back in the big time.

“Aren't you going to snap Mr. Jim Jerome?” Dolly asked him. “He's just back in Hollywood today—from England. He says they're making better pictures; he's convinced them not to take out time for tea in the middle of the big emotional scenes.”

George saw them there together and he had a feeling of great relief—that everything was coming out all right. But after the party, when the candles had squatted down into little tallow drips, he detected a look of uncertainty in Dolly's face—the first he had ever seen there. In the car going back to the hotel bungalow she told him what had happened.

“He wants me to give up pictures and marry him. Oh, he's set on it. The old business of two careers and so forth. I wonder—”

“Yes?”

“I don't wonder. He thinks I'm through. That's part of it.”

“Could you fall in love with him?”

She looked at George—laughed.

“Could I? Let me see—”

“He's always loved you. He almost told me once.”

“I know. But it would be a strange business; I'd have nothing to do—just like Hennen.”

“Then don't marry him; wait it out. I've thought of a dozen ideas to make money.”

“George, you terrify me,” she said lightly. “Next thing I'll find racing forms in your pocket, or see you down on Hollywood Boulevard with an oil well angle—and your hat pulled down over your eyes.”

“I mean honest money,” he said defiantly.

“You could go on the stage like Freddie and I'll be your Aunt Prissy.”

“Well, don't marry him unless you want to.”

“I wouldn't mind—if he was just passing through; after all every woman needs a man. But he's so set about everything. Mrs. James Jerome. No! That isn't the way I grew to be and you can't help the way you grow to be, can you? Remind me to wire him tonight—because tomorrow he's going East to pick up talent for Portrait of a Woman.”

George wrote out and telephoned the wire, and three days later went once more to the big house in the valley to pick up a scattering of personal things that Dolly wanted.

Phyllis was there—the deal for the house was closed, but she made no objections, trying to get him to take more and winning a little of his sympathy again, or at least bringing back his young assurance that there's good in everyone. They walked in the garden, where already workmen had repaired the cables and were testing the many-colored bulbs around the pool.

“Anything in the house she wants,” Phyllis said. “I'll never forget that she was my inspiration and ideal, and frankly what's happened to her might happen to any of us.”

“Not exactly,” objected George. “She has special things happen because she's a ‘grande cliente.’ ”

“I never knew what that meant,” laughed Phyllis. “But I hope it's a consolation if she begins brooding.”

“Oh, she's too busy to brood. She started work on Portrait of a Woman this morning.”

Phyllis stopped in her promenade.

“She did! Why, that was for Katharine Cornell, if they could persuade her! Why, they swore to me—”

“They didn't try to persuade Cornell or anyone else. Dolly just walked into the test—and I never saw so many people crying in a projection room at once. One guy had to leave the room—and the test was just three minutes long.”

He caught Phyllis' arm to keep her from tripping over the board into the pool. He changed the subject quickly.

“When are you—when are you two moving in?”

“I don't know,” said Phyllis. Her voice rose. “I don't like the place! She can have it all—with my compliments.”

But George knew that Dolly didn't want it. She was in another street now, opening another big charge account with life. Which is what we all do after a fashion—open an account and then pay.

This story was written in Hollywood in July 1939 and led to Fitzgerald's break with Harold Ober over the agent's refusal to resume the policy of making advances against unsold stories. At this time Fitzgerald was hoping to underwrite work on The Last Tycoon by returning to the high-paying magazines. Apart from the Pat Hobby series, he was cautious about writing Hollywood stories because he was saving the best material for his novel. He submitted “Director's Special,” the first version of this story, to The Saturday Evening Post, which declined it because the ending was not clear. He revised it in August, but the Post declined it again. Fitzgerald admitted to Ober: “It is not quite a top story—and there's nothing much I can do about it. The reasons are implicit in the structure which wanders a little. ... It simply couldn't stand any cutting whatsoever and one of the reasons for its faults is that I was continually conscious in the first draft of that Collier length and left out all sorts of those sideshows that often turn out to be highspots.”

Hoping to establish a connection with Collier's in the summer of 1939, Fitzgerald submitted several stories to fiction editor Kenneth Littauer—all of which were declined. With one of these stories Fitzgerald sent an assessment of his situation:

... it isn't particularly likely that I'll write a great many more stories about young love. I was tagged with that by my first writings up to 1925. Since then I have written stories about young love. They have been done with increasing difficulty and increasing insincerity. I would be either a miracle man or a hack if I could go on turning out an identical product for three decades.

I know that is what's expected of me, but in that direction the well is pretty dry and I think I am much wiser in not trying to strain for it but rather to open up a new well, a new vein. You see, I not only announced the birth of my young illusions in This Side of Paradise but pretty much the death of them in some of my last Post stories like “Babylon Revisited.” Lorimer seemed to understand this in a way. Nevertheless, an overwhelming number of editors continue to associate me with an absorbing interest in young girls—an interest that at my age would probably land me behind the bars.

After Collier's and Cosmopolitan declined it, Fitzgerald withdrew the story.

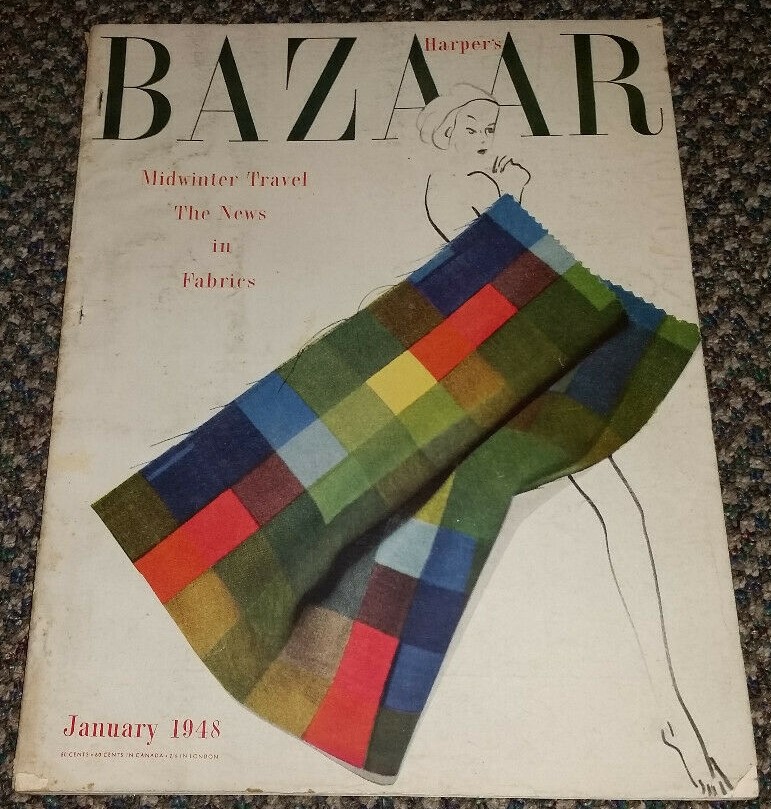

Published in Harper's Bazaar magazine (January 1948).

Not illustrated.