How to Waste Material: A Note on My Generation

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Ever since Irving’s preoccupation with the necessity for an American background, for some square miles of cleared territory on which colorful varia might presently arise, the question of material has hampered the American writer. For one Dreiser who made a single minded and irreproachable choice there have been a dozen like Henry James who have stupid-got with worry over the matter, and yet another dozen who, blinded by the fading tail of Walt Whitman’s comet, have botched their books by the insincere compulsion to write “significantly” about America.

Insincere because it is not a compulsion found in themselves—it is “literary” in the most belittling sense. During the past seven years we have had at least half a dozen treatments of the American farmer, ranging from New England to Nebraska; at least a dozen canny books about youth, some of them with surveys of the American universities for background; more than a dozen novels reflecting various aspects of New York, Chicago, Washington, Detroit, Indianapolis, Wilmington, and Richmond; innumerable novels dealing with American politics, business, society, science, racial problems, art, literature, and moving pictures, and with Americans abroad at peace or in war; finally several novels of change and growth, tracing the swift decades for their own sweet lavender or protesting vaguely and ineffectually against the industrialization of our beautiful old American life. We have had an Arnold Bennett for every five towns—surely by this time the foundations have been laid! Are we competent only to toil forever upon a never completed first floor whose specifications change from year to year?

In any case we are running through our material like spendthrifts—just as we have done before. In the Nineties there began a feverish search for any period of American history that hadn’t been “used,” and once found it was immediately debauched into a pretty and romantic story. These past seven years have seen the same sort of literary gold rush; and for all our boasted sincerity and sophistication, the material is being turned out raw and undigested in much the same way. One author goes to a midland farm for three months to obtain the material for an epic of the American husbandmen! Another sets off on a like errand to the Blue Ridge Mountains, a third departs with a Corona for the West Indies—one is justified in the belief that what they get hold of will weigh no more than the journalistic loot brought back by Richard Harding Davis and John Fox, Jr., twenty years ago.

Worse, the result will be doctored up to give it a literary flavor. The farm story will be sprayed with a faint dilution of ideas and sensory impressions from Thomas Hardy; the novel of the Jewish tenement block will be festooned with wreaths from “Ulysses” and the later Gertrude Stein; the document of dreamy youth will be prevented from fluttering entirely away by means of great and half great names—Marx, Spencer, Wells, Edward Fitzgerald—dropped like paper weights here and there upon the pages. Finally the novel of business will be cudgeled into being satire by the questionable but constantly reiterated implication that the author and his readers don’t partake of the American commercial instinct and aren’t a little jealous.

And most of it—the literary beginnings of what was to have been a golden age—is as dead as if it had never been written. Scarcely one of those who put so much effort and enthusiasm, even intelligence, into it, got hold of any material at all.

To a limited extent this was the fault of two men—one of whom, H. L. Mencken, has yet done more for American letters than any man alive. What Mencken felt the absence of, what he wanted, and justly, back in 1920, got away from him, got twisted in his hand. Not because the “literary revolution” went beyond him but because his idea had always been ethical rather than aesthetic. In the history of culture no pure aesthetic idea has ever served as an offensive weapon. Mencken’s invective, sharp as Swift’s, made its point by the use of the most forceful prose style now written in English. Immediately, instead of committing himself to an infinite series of pronouncements upon the American novel, he should have modulated his tone to the more urbane, more critical one of his early essay on Dreiser.

But perhaps it was already too late. Already he had begotten a family of hammer and tongs men—insensitive, suspicious of glamour, preoccupied exclusively with the external, the contemptible, the “national” and the drab, whose style was a debasement of his least effective manner and who, like glib children, played continually with his themes in his maternal shadow. These were the men who manufactured enthusiasm when each new mass of raw data was dumped on the literary platform—mistaking incoherence for vitality, chaos for vitality. It was the “new poetry movement” over again, only that this time its victims were worth the saving. Every week some new novel gave its author membership in “that little band who are producing a worthy American literature.” As one of the charter members of that little band I am proud to state that it has now swollen to seventy or eighty members.

And through a curious misconception of his work, Sherwood Anderson must take part of the blame for this enthusiastic march up a blind alley in the dark. To this day reviewers solemnly speak of him as an inarticulate, fumbling man, bursting with ideas—when, on the contrary, he is the possessor of a brilliant and almost inimitable prose style, and of scarcely any ideas at all. Just as the prose of Joyce in the hands of, say, Waldo Frank becomes insignificant and idiotic, so the Anderson admirers set up Hergesheimer as an anti-Christ and then proceed to imitate Anderson’s lapses from that difficult simplicity they are unable to understand. And here again critics support them by discovering merits in the very disorganization that is to bring their books to a timely and unregretted doom.

Now the business is over. “Wolf” has been cried too often. The public, weary of being fooled, has gone back to its Englishmen, its memoirs and its prophets. Some of the late brilliant boys are on lecture tours (a circular informs me that most of them are to speak upon “the literary revolution!”), some are writing pot boilers, a few have definitely abandoned the literary life—they were never sufficiently aware that material, however closely observed, is as elusive as the moment in which it has its existence unless it is purified by an incorruptible style and by the catharsis of a passionate emotion.

Of all the work by the young men who have sprung up since 1920 one book survives—“The Enormous Room” by e. e. cummings. It is scarcely a novel; it doesn’t deal with the American scene; it was swamped in the mediocre downpour, isolated—forgotten. But it lives on, because those few who cause books to live have not been able to endure the thought of its mortality. Two other books, both about the war, complete the possible salvage from the work of the younger generation—“Through the Wheat” and “Three Soldiers,” but the former despite its fine last chapters doesn’t stand up as well as “Les Croix de Bois” and “The Red Badge of Courage,” while the latter is marred by its pervasive flavor of contemporary indignation. But as an augury that someone has profited by this dismal record of high hope and stale failure comes the first work of Ernest Hemingway.

II

“In Our Time” consists of fourteen stories, short and long, with fifteen vivid miniatures interpolated between them. When I try to think of any contemporary American short stories as good as “Big Two-Hearted River,” the last one in the book, only Gertrude Stein’s “Melanctha,” Anderson’s “The Egg,” and Lardner’s “Golden Honeymoon” come to mind. It is the account of a boy on a fishing trip—he hikes, pitches his tent, cooks dinner, sleeps, and next morning casts for trout. Nothing more—but I read it with the most breathless unwilling interest I have experienced since Conrad first bent my reluctant eyes upon the sea.

The hero, Nick, runs through nearly all the stories, until the book takes on almost an autobiographical tint—in fact “My Old Man,” one of the two in which this element seems entirely absent, is the least successful of all. Some of the stories show influences but they are invariably absorbed and transmuted, while in “My Old Man” there is an echo of Anderson’s way of thinking in those sentimental “horse stories,” which inaugurated his respectability and also his decline four years ago.

But with “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife,” “The End of Something,” “The Three Day Blow,” “Mr. and Mrs. Elliot,” and “Soldier’s Home” you are immediately aware of something temperamentally new. In the first of these a man is backed down by a half breed Indian after committing himself to a fight. The quality of humiliation in the story is so intense that it immediately calls up every such incident in the reader’s past. Without the aid of a comment or a pointing finger one knows exactly the sharp emotion of young Nick who watches the scene.

The next two stories describe an experience at the last edge of adolescence. You are constantly aware of the continual snapping of ties that is going on around Nick. In the half stewed, immature conversation before the fire you watch the awakening of that vast unrest that descends upon the emotional type at about eighteen. Again there is not a single recourse to exposition. As in “Big Two-Hearted River,” a picture—sharp, nostalgic, tense—develops before your eyes. When the picture is complete a light seems to snap out, the story is over. There is no tail, no sudden change of pace at the end to throw into relief what has gone before.

Nick leaves home penniless; you have a glimpse of him lying wounded in the street of a battered Italian town, and later of a love affair with a nurse on a hospital roof in Milan. Then in one of the best of the stories he is home again. The last glimpse of him is when his mother asks him, with all the bitter world in his heart, to kneel down beside her in the dining room in Puritan prayer.

Anyone who first looks through the short interpolated sketches will hardly fail to read the stories themselves. “The Garden at Mons” and “The Barricade” are profound essays upon the English officer, written on a postage stamp. “The King of Greece’s Tea Party,” “The Shooting of the Cabinet Ministers,” and “The Cigar-store Robbery” particularly fascinated me, as they did when Edmund Wilson first showed them to me in an earlier pamphlet, over two years ago.

Disregard the rather ill considered blurbs upon the cover. It is sufficient that here is no raw food served up by the railroad restaurants of California and Wisconsin. In the best of these dishes there is not a bit to spare. And many of us who have grown weary of admonitions to “watch this man or that” have felt a sort of renewal of excitement at these stories wherein Ernest Hemingway turns a corner into the street.

Editorial

This essay—or review—was printed in The Bookman in May, 1926. It was Fitzgerald’s contribution to a campaign he was waging to get wide recognition for the work of Hemingway, whom he had recently got to know in Paris; the campaign is amusingly described by Glenway Wescott in “The Moral of Scott Fitzgerald” and there are some tangential references to it in “The Torrents of Spring”. The essay is a rare illustration of how acute Fitzgerald’s adult literary insight was: in the thirty years since these notes on “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife,” “The End of Something,” and “Soldier’s Home” were written, they have seldom been improved on; and the judgments of such different writers as Sherwood Anderson and Waldo Frank are equally penetrating.

The vigor of Fitzgerald’s attack on the fashionable concern at that time for books about American life may seem excess to modern readers, but it was not. It shows, moreover, how conscious Fitzgerald was by this time of what had been, to begin with, only an instinct with him, the crucial need to imagine fully whatever material one uses. What he is really attacking here is the failure of imagination in most of the people who were writing the fashionable books about the American peasants, and what he is asserting is the imagination’s triumphant emergence in a book which is thoroughly American in another and better sense. It is typical of him that he thought of the unimagined book as a waste of material, as if the material of literature could be exhausted, like an oil well or a bank account. It is important that this realization of a then nearly unknown writer’s achievement shows us how his sense of responsibility and—in a round-about way—his guilt at not satisfying it were increasing.

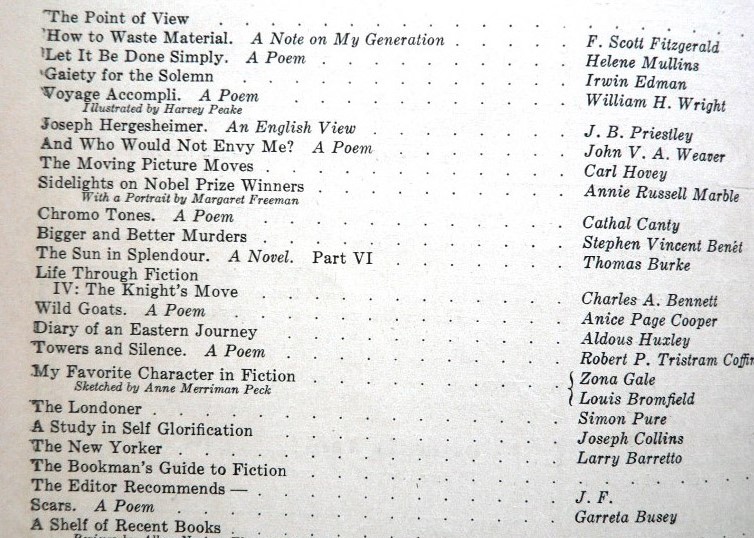

Published in The Bookman magazine (May 1926).

Not illustrated.