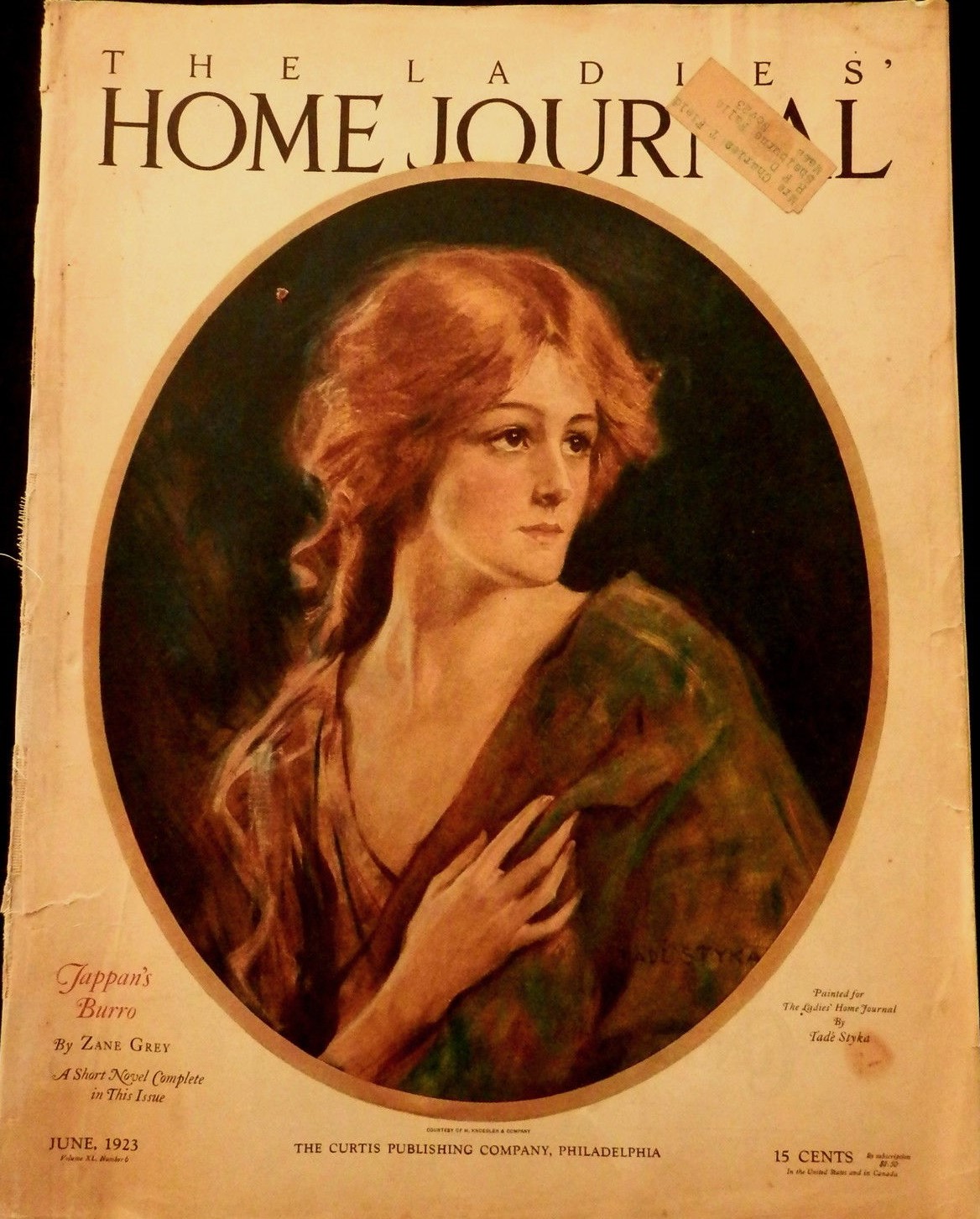

Imagination—and a Few Mothers

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Back in the days of tenement uplift, the homes of tired stevedores and banana peddlers were frequently invaded by pompous dowagers who kept their limousines purring at the curb. “Giuseppi,” say the pompous dowagers, “what you need to brighten up your home is a game of of charades every evening.”

“Charade?” inquires the bewildered Giuseppi.

“Family charades,” beam the dowagers. “For instance, suppose some night your wife and the girls take the name ’Viscountess Salisbury,’ or the words ’initiative and referendum,’ and act them out—and you and the boys can guess what words they’re acting. So much more real fun than the saloon.”

Having sown the good seed, the dowagers reenter their limousines and drive to the next Giuseppi on their list, a list made out by the Society for Encouraging Parlor Games in Poor Families.

Thus went the attempt from on high to bring imagination into the home, an attempt about as successful as the current effort to clothe the native Hawaiians in dollar-eighty-five cheesecloth Mother Hubbards manufactured in Paterson, New Jersey.

The average home is a horribly dull place. This is a platitude; it’s so far taken for granted that it’s the basis of much of our national humor. The desire of the man for the club and the wife for the movie—as Shelley did not put it—has recently been supplemented by the cry of the child for the moonlight ride.

The statistics compiled last year by the state of Arkansas show that of every one hundred wives thirty-seven admit that they married chiefly to get away from home. The figures are appalling. That nineteen of the thirty-seven wished themselves home again as soon as they were married does not mitigate the frightful situation.

It is easy to say that the home fails chiefly in imagination. Rut an imagination under good control is about as rare a commodity as radium, and does not consist of playing charades or giving an imitation of Charlie Chaplin or putting papier-mache shades on the 1891 gas jets; imagination is an attitude toward living. It is a putting into the terrific, lifelong, age-old fight against domestic dullness all the energy that goes into worry and self-justification and nagging, which are the pet devices of all of us for whiling away the heavy hours.

The word energy at once brings up the picture of a big, bustling woman, breathing hard through closed lips, rushing from child to child and trying to organize a dear little Christmas play in the parlor. But that isn’t at all the kind of imagination I mean.

There are several kinds. For example, I once knew the mother of a family, a Mrs. Judkins, who had a marvelous imagination. If things had been a little different, Mrs. Judkins might have sold her imagination to the movies or the magazines, or invented a new kind of hook-and-eye. Or she might have put it into that intricate and delicate business of running a successful home. Did Mrs. Judkins use her imagination for these things? She did not! She had none left to use.

Her imagination had a leak in it, and its stuff was dissipated hourly into thin air—in this fashion: At six a.m. Mrs. Judkins awakes. She lies in bed. She begins her daily worry. Did, or did not, her daughter Anita look tired last night when she came in from that dance? Yes; she did. She had dark circles. Dark circles—a bogy of her childhood. Mrs. Judkins remembers how her own mother always worried about dark circles. Without doubt Anita is going into a nervous decline. How ghastly! Think of that Mrs.—what was her name?—who had the nervous decline at—at—what was that place? Think of it! Appalling! Well, I’ll—I’ll ask her to go to a doctor; but what if she won’t go? Maybe I can get her to stay home from dances for—for a month.

Out of her bed springs Mrs. Judkins in a state of nervous worry. She is impelled by a notion of doing some vague, nervous thing to avoid some vague, nervous catastrophe.She is already fatigued, because she shouldhave gone back to sleep for an hour; but sleep is now out of the question. Her wonderful imagination has conjured up Anita’s lapse into a bed of pain, her last words—something about “going back to the angels”—and her pitiful extinction.

Anita, who is seventeen and a healthy, hardy flapper, has merely plunged healthily ami hardily into having a good lime. For two nights in succession she has been out late at dances. The second night she was tired and developed dark circles. Today she will sleep until twelve o’clock, if Mrs. Judkins doesn’t wake her to ask her how she feels, and will get up looking like a magazine cover.

But it is only eight o’clock now, and we must return to Mrs. Judkins. She has tiptoed in to look at the doomed Anita, and on her way has glanced into the room where sleeps Clifford Judkins, third, age twelve. Her imagination is now running at fever heat. It is started for the day and will pulsate at the rate of sixty vivid images a minute until she falls into a weary coma at one o’clock tonight.

So she endows Clifford with dark circles also.

Poor Clifford! She decides not to wake him for school. He’s not strong enough. She’ll write a note to his teacher and explain. He looked tired yesterday when he came in from playing baseball. Baseball! Another ghastly thought! Why, suppose—

But I will not depress you by taking you through all the early hours of Mrs. Judkins’ morning; because she is depressing. A human being in a nervous, worried state is one of the most depressing things in the world. Mrs. Judkins is exhausted already so far as having the faintest cheerful effect on anyone else is concerned. In fact, after breakfast Mr. Judkins leaves the house with the impression that things are going pretty badly at home and that life’s a pretty dismal proposition.

But before he left he did a very unfortunate thing. Something in the newspaper made him exclaim that if they passed that Gunch-Bobly tariff law his business was going to the dogs. It was merely a conventional grumble. Complaining about the Gunch-Bobly tariff law is his pet hobby, but--

He has put a whole bag of grist—does grist come in bags?—into the mill of Mrs. Judkins’ imagination. By the time he reaches the street car Mrs. Judkins has got him into bankruptcy. By the time he is downtown he has—though he doesn’t know it—been spending a year in prison, with a woman and two starving children calling for him outside the gates. When he enters his office he is unconsciously entering the poorhouse, there to weep out a miserable old age.

Not According to Model

But enough; a few more hours of Mrs. Judkins’ day would exhaust me and you, as it exhausts everybody with whom she comes into contact.

There are many Mrs. Judkinses, and I could go on forever. But I will spare you, for I want to talk about one woman who together with several others I know fought the good fight against the dullness and boredom of the home and, by an unusual device, won a triumphant and deserved victory

I’m going to tell you about a charming woman who, as I have said, used her imagination in an unusual way. Hers was the happiest home I ever knew.

Did she work for a while in her husband’s office and learn how his business was run, so that she could talk to him about it in the evenings? Reader, she did not. Did she buy a football guide and master the rules- so that she could discuss the game understandingly with her sons? No; she didn’t. Nor did she organize a family orchestra in which Clarence played the drum, Maisee the harp and Vivian the oboe. She knew nothing about football, nor did she ever intend to. Her remarks on her husband’s business were delightfully vague. He was a manufacturer of stationery, and I think that in some confused way she imagined that he ran the Post Office Department.

No; she was not one of those appalling women who know more about the business of everybody in the house than anyone knows about his own. She never bored her boys by instructing them in football, though she occasionally delighted them by her ludicrous misapprehensions of how it was played. And she never dragged the paper industry onto the domestic hearth. She couldn’t even solve her own daughter’s algebra problems; she admitted it and didn’t try. In fact, she was not at all the model mother, as mapped out by Miss Emily Hope Demster, of the Wayondotte Valley Normal School, in her paper on Keeping Ahead of Your Children.

She used her imagination in a finer and more far-seeing way. She knew that a home violently dominated by a strong-minded woman has a way of turning the girls into dependent shadows and the boys into downright ninnies. She realized that the inevitable growth of a healthy child is a drifting away from the home.

She Kept Young for Herself

So Mrs. Paxton protected herself by enjoying life quite selfishly in her own way. She did not keep young with her children or for her children—two hollow and disastrous phrases—she kept young for herself. When her children were tiresome she did not scold them; she told them that they bored her.

One of her sons was remarkably handsome and scholastically an utter dunce. I believe she liked him a little the best of the three; but when he was dull she laughed at him and told him so. She called him” the dumb one” without blame or malice, but always with humor. She could do this, because she thought of her children as persons, not as miraculous pieces of personal property.

A man doesn’t have to be very smart to do well in this world. In fact, Harry Paxton, though he never could get into college, has done very well since. And the fact that he is ’’dumb” is to this day a standing joke between him and his mother.

Mrs. Paxton’s children were always treated as though they were grown. As they grew older, their private lives were more and more respected and let alone. They chose their schools; they chose their activities; and so long as their friends did not bore Mrs. Pax-ton or at least were not personally inflicted on her, they chose their own friends. She herself had always been a musician; but as the children showed no predilections in that direction, no music lessons were ever suggested to them. As children, they scarcely existed to her—except in time of sickness; but as persons she got from them a sort of amazed enjoyment. One of her boys was brilliant; she was enormously impressed, exactly as though he had been someone she had read about in the paper. Once she remarked to a shocked and horrified group of mammas that her own daughter. Prudence, would be pretty if she didn’t dress so abominably.

Meanwhile she was protecting herself by having a good time, independently of her children. She did as she had always done. Until her children were old enough to share in her amusements, she let them alone in theirs. So far as their amusements were intrinsically interesting they interested her,but she seldom spoiled their frame of “pom-pom-pull-away” by playing it with them. She knew that children are happier by themselves, and if she played with them it was only because the wanted the exercise.

It was a sincerely happy home. The children were not compelled or even urged to love one another; and in consequence they grew up with a strong and rather sentimental mutual liking.

Mrs. Paxton’s home was a success, because she had a good time in it herself. The children never considered that it was run entirely for their benefit. It was a place where they could do what they liked; but it was distinctly not a place where they could do what they liked to somebody else. It neither restricted them nor did it prostrate itself abjectly before them. It was a place where their lather and mother seemed unforgetably happy over mysteries of their own. Even now they pause and wonder what were those amazing and incomprehensible jokes they could not understand. They were welcome to participate in the conversation, if they could, but it was never tempered into one-syllable platitudes for their minds.

Later, when Prudence came to her mother for worldly advice, Mrs. Paxton gave it—gave it as she would have given it to a friend.

So with her son at college. He never felt that there was someone standing behind him with all-forgiving arms. He was on his own. If he failed he would not be blamed, lectured or wept over; but he was not going to be bolstered through with the help of private tutors. Why not? Simply because tutoring would have meant that his mother would have to give up a new dress which she wanted and didn’t intend to give up—a straightforward, just and nsentimental reason.

Making Eminent Men

The home was never dull, because it was never compulsory; one could take it or leave it. It was a place where father and mother were happy. It was never insufficient; it had never promised to be a sort of dowdy, downy bed where everyone could indulge his bad habits, be careless in dress and appearance, nag and snarl in short, a breeding place for petty vices, weaknesses and insufficiencies. In return for giving up the conventional privileges of the mother, of dominating the children and endowing them with convenient, it erroneous, ideas, Mrs. Paxton claimed the right that she should not be dominated, discomforted or “used” by the children.

It is very easy to call her an “unnatural” mother; but being a “natural, old-fashioned mother” is just about the easiest groove for a woman to slide into. It takes much more imagination to be Mrs. Paxton’s kind. Motherhood, as a blind, unreasoning habit, is something we have inherited from our ancestors of the cave. This abandonment to the maternal instinct was universal, so we made it sacred—” Hands Off!” But just as we develop, century by century, we tight against the natural, whether it’s the natural (and “sacred”?) instinct to kill what we hate or the temptation to abandon oneself to one’s children.

It is a commonplace to say that eminent men come, as a rule, from large families; but this is not due to any inherent virtue of the large family in itself; it is because in a large family the children’s minds are much more liable to be left alone; each child is not ineradically stamped with the particular beliefs, errors, convictions, aversions and bogies that haunted the mother in the year 1889 or 1901 or 1922 as the case might be. In large families no one child can be in so much direct contact with its parents.

Returning to Mrs. Paxton, I want to set down here what happened to her. The three children grew up and left her as children have a way of doing. She missed them, but it did not end her active life, as her active life had always gone along quite independently of them. She never became the miserable mother of the movies, broken by the separation, thankful for one homecoming a year, existing for and ravenously devouring the four letters a month she receives from her scattered daughters and sons. It is some day proved to all women that they do not own their children. They were never meant to.

And Mrs. Paxton had been wise enough never to pretend she owned her children. She had had enough imagination to see that they were primarily persons; and, except in the aforementioned times of sickness, it was as persons that she first thought of them.

“The Home is Oversufflcient”

So her life went on as it had gone on be-fore. As she grew older her amusements changed, but she grew old slowly. The strange part of it is that the children think of her as a person, not as a” mother” who has to be written to once a fortnight and who will excuse their most intolerable shortcomings.

“What? You’ve never met my mother?” they say. “Oh, she’s a most amazing, most interesting person. She’s perfectly charming. You ought to meet her.”

They remember their home as the place where their own interests were unhindered, and where, if they were bores, they were snubbed as bores should be snubbed.

“No,” cries the sentimentalist; “give me my old wrinkled mother who never thought of anything but me, who gave me the clothes off her back and grew old doing things for my pleasure. Why, I’m the only thing she was ever interested in.”

And that’s the fate of the mother we exalt at present—on screen and in sob story. Flatter her, “respect” her—and leave her alone. She never had the imagination to consider her children as persons when they were young, so they are unable to think of her as a person when she is old.

They send her a shawl for Christmas. When she visits them twice a year they take her to the Hippodrome; “Mother wouldn’t like these new-fashioned shows.” She is not a person; she is “poor” mother. Old at fifty, she eats in her room when there’s young company at dinner. She has given her children so much in selfish, unreasoning love that when they go from her she has nothing left except the honorary title “mother “on which to feed her ill-nourished soul.

We have learned at last on the advice of our doctors to leave babies alone. No longer do we tease and talk to and “draw out” the baby all day, and wonder why it is fretful and cross and nervous at the day’s end. A mother’s love for a child is no longer measured by the number of times it cries for her every night. Perhaps some day we’ll leave our children alone, too, and spend our time on ourselves. The home is not so much insufficient as it is oversufficient. It is cloying; it tries too hard. A woman happy with her husband is worth a dozen child worshipers, in her influence on the child. And all the energy spent in “molding” the child is not as effective as the imagination to see the child as a “person,” because sooner or later a person is what that child is going to be.

Editorial Note

Mr. Fitzgerald is one of the most brilliant writers of the modernist school; and his article “Imagination—and a Few Mothers” is published solely as a representation of the modernist viewpoint. In the older generation all mothers were of a type with his “Mrs. Judkins”—and even today the mother who docs not worry about her children is the exception. But we cannot help being interested in the ultra-modern methods by which Mrs. Paxton brought up her sons and daughters and made what Mr. Fitzgerald calls “the happiest home I ever knew.”

Published in The Ladies' Home Journal magazine (June 1923).

Illustrations by Nancy Fay.