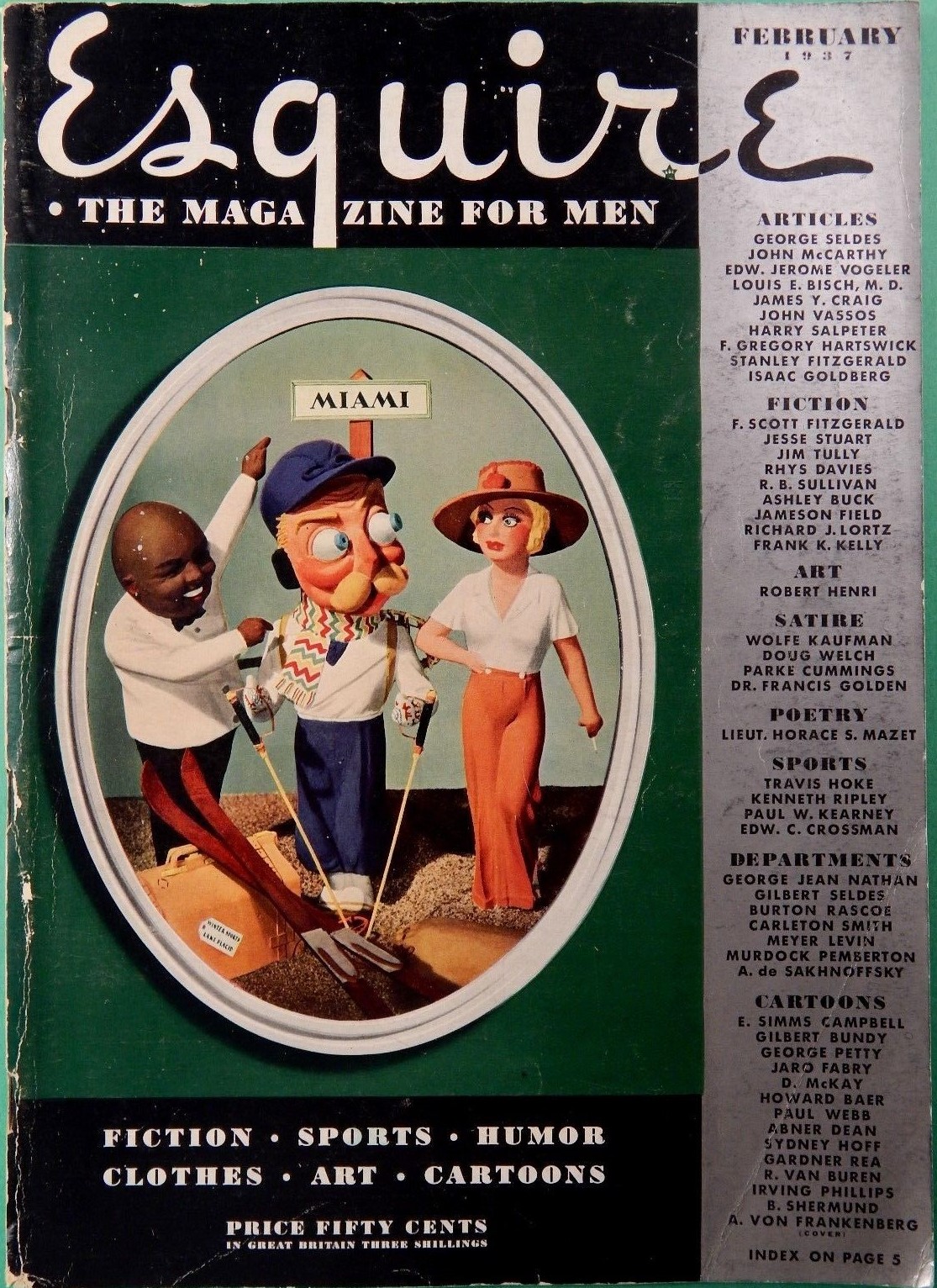

An Alcoholic Case

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“Let—go—that—Oh-h-h! Please, now, will you? Don’t start drinking again! Come on—give me the bottle. I told you I’d stay awake givin’ it to you. Come on. If you do like that a-way—then what are you going to be like when you go home. Come on—leave it with me—I’ll leave half in the bottle. Pul-lease. You know what Dr. Carter says—I’ll stay awake and give it to you, or else fix some of it in the bottle—come on—like I told you, I’m too tired to be fightin’ you all night… All right, drink your fool self to death.”

“Would you like some beer ?” he asked.

“No, I don’t want any beer. Oh, to think that I have to look at you drunk again. My God!”

“Then I’ll drink the Coca-Cola.”

The girl sat down panting on the bed.

“Don’t you believe in anything?” she demanded.

“Nothing you believe in—please—it’ll spill.”

She had no business there, she thought, no business trying to help him. Again they struggled, but after this time he sat with his head in his hands awhile, before he turned around once more.

“Once more you try to get it I’ll throw it down,” she said quickly. “I will—on the tiles in the bathroom.”

“Then I’ll step on the broken glass—or you’ll step on it.”

“Then let go—oh you promised—”

Suddenly she dropped it like a torpedo, sliding underneath her hand and slithering with a flash of red and black and the words: SIR GALAHAD, DISTILLED LOUISVILLE GIN. He took it by the neck and tossed it through the open door to the bathroom.

It was on the floor in pieces and everything was silent for a while and she read Gone With the Wind about things so lovely that had happened long ago. She began to worry that he would have to go into the bathroom and might cut his feet, and looked up from time to time to see if he would go in. She was very sleepy—the last time she looked up he was crying and he looked like an old Jewish man she had nursed once in California; he had had to go to the bathroom many times. On this case she was unhappy all the time but she thought:

“I guess if I hadn’t liked him I wouldn’t have stayed on the case.”

With a sudden resurgence of conscience she got up and put a chair in front of the bathroom door. She had wanted to sleep because he had got her up early that morning to get a paper with the story of the Yale-Dartmouth game in it and she hadn’t been home all day. That afternoon a relative of his had come to see him and she had waited outside in the hall where there was a draught with no sweater to put over her uniform.

As well as she could she arranged him for sleeping, put a robe over his shoulders as he sat slumped over his writing table, and one on his knees. She sat down in the rocker but she was no longer sleepy; there was plenty to enter on the chart and treading lightly about she found a pencil and put it down:

Pulse 120

Respiration 25

Temp. 98—98.4—98.3

Remarks—

—She could make so many:

Tried to get bottle of gin. Threw it away and broke it.

She corrected it to read:

In the struggle it dropped and mas broken. Patient teas generally difficult.

She started to add as part of her report: I never want to go on an alcoholic case again, but that wasn’t in the picture. She knew she could wake herself at seven and clean up everything before his niece awakened. It was all part of the game. But when she sat down in the chair she looked at his face, white and exhausted, and counted his breathing again, wondering why it had all happened. He had been so nice to-day, drawn her a whole strip of his cartoon just for fun and given it to her. She was going to have it framed and hang it in her room. She felt again his thin wrists wrestling against her wrist and remembered the awful things he had said, and she thought too of what the doctor had said to him yesterday:

“You’re too good a man to do this to yourself.”

She was tired and didn’t want to clean up the glass on the bathroom floor, because as soon as he breathed evenly she wanted to get him over to the bed. But she decided finally to clean up the glass first; on her knees, searching a last piece of it, she thought:

—This isn’t what I ought to be doing. And this isn’t what he ought to be doing.

Resentfully she stood up and regarded him. Through the thin delicate profile of his nose came a light snore, sighing, remote, inconsolable. The doctor had shaken his head in a certain way, and she knew that really it was a case that was beyond her. Besides, on her card at the agency was written, on the advice of her elders, “No Alcoholics.”

She had done her whole duty, but all she could think of was that when she was struggling about the room with him with that gin bottle there had been a pause when he asked her if she had hurt her elbow against a door and that she had answered: “You don’t know how people talk about you, no matter how you think of yourself—” when she knew he had a long time ceased to care about such things.

The glass was all collected—as she got out a broom to make sure, she realized that the glass, in its fragments, was less than a window through which they had seen each other for a moment. He did not know about her sister, and Bill Markoe whom she had almost married, and she did not know what had brought him to this pitch, when there was a picture on his bureau of his young wife and his two sons and him, all trim and handsome as he must have been five years ago. It was so utterly senseless—as she put a bandage on her finger where she had cut it while picking up the glass she made up her mind she would never take an alcoholic case again.

II

It was early the next evening. Some Halloween jokester had split the side windows of the bus and she shifted back to the Negro section in the rear for fear the glass might fall out. She had her patient’s cheque but no way to cash it at this hour; there was a quarter and a penny in her purse.

Two nurses she knew were waiting in the hall of Mrs Hixson’s Agency.

“What kind of case have you been on?”

“Alcoholic,” she said.

“Oh yes—Gretta Hawks told me about it—you were on with that cartoonist who lives at the Forest Park Inn.”

“Yes, I was.”

“I hear he’s pretty fresh.”

“He’s never done anything to bother me,” she lied. “You can’t treat them as if they were committed—”

“Oh, don’t get bothered—I just heard that around town—oh, you know—they want you to play around with them—”

“Oh, be quiet!” she said, surprised at her own rising resentment.

In a moment Mrs Hixson came out and, asking the other two to wait, signalled her into the office.

“I don’t like to put young girls on such cases,” she began. “I got your call from the hotel.”

“Oh, it wasn’t bad, Mrs Hixson. He didn’t know what he was doing and he didn’t hurt me in any way. I was thinking much more of my reputation with you. He was really nice all day yesterday. He drew me—”

“I didn’t want to send you on that case.” Mrs Hixson thumbed through the registration cards. “You take T.B. cases, don’t you ? Yes, I see you do. Now here’s one—”

The phone rang in a continuous chime. The nurse listened as Mrs Hixson’s voice said precisely:

“I will do what I can—that is simply up to the doctor…. That is beyond my jurisdiction… Oh, hello, Hattie, no, I can’t now. Look, have you got any nurse that’s good with alcoholics ? There’s somebody up at the Forest Park Inn who needs somebody. Call back will you?”

She put down the receiver. “Suppose you wait outside. What sort of man is this, anyhow ? Did he act indecently?”

“He held my hand away,” she said, “so I couldn’t give him an injection.”

“Oh, an invalid he-man,” Mrs Hixson grumbled. “They belong in sanatoria. I’ve got a case coming along in two minutes that you can get a little rest on. It’s an old woman—”

The phone rang again. “Oh, hello, Hattie…. Well, how about that big Svensen girl ? She ought to be able to take care of any alcoholic… How about Josephine Markham? Doesn’t she live in your apartment house ? … Get her to the phone.” Then after a moment, “Joe, would you care to take the case of a well-known cartoonist, or artist, whatever they call themselves, at Forest Park Inn? … No, I don’t know, but Dr Carter is in charge and will be around about ten o’clock.”

There was a long pause; from time to time Mrs Hixson spoke:

“I see. … Of course, I understand your point of view. Yes, but this isn’t supposed to be dangerous—just a little difficult. I never like to send girls to a hotel because I know what riff-raff you’re liable to run into… No, I’ll find somebody. Even at this hour. Never mind and thanks. Tell Hattie I hope that the hat matches the negligee…”

Mrs Hixson hung up the receiver and made notations on the pad before her. She was a very efficient woman. She had been a nurse and had gone through the worst of it, had been a proud, idealistic, overworked probationer, suffered the abuse of smart internes and the insolence of her first patients, who thought that she was something to be taken into camp immediately for premature commitment to the service of old age. She swung around suddenly from the desk.

“What kind of cases do you want? I told you I have a nice old woman—”

The nurse’s brown eyes were alight with a mixture of thoughts—the movie she had just seen about Pasteur and the book they had all read about Florence Nightingale when they were student nurses. And their pride, swinging across the streets in the cold weather at Philadelphia General, as proud of their new capes as debutantes in their furs going in to balls at the hotels.

“I—I think I would like to try the case again,” she said amid a cacophony of telephone bells. “I’d just as soon go back if you can’t find anybody else.”

“But one minute you say you’ll never go on an alcoholic case again and the next minute you say you want to go back to one.”

“I think I overestimated how difficult it was. Really, I think I could help him.”

“That’s up to you. But if he tried to grab your wrists.”

“But he couldn’t,” the nurse said. “Look at my wrists: I played basketball at Waynesboro High for two years. I’m quite able to take care of him.”

Mrs Hixson looked at her for a long minute. “Well, all right,” she said. “But just remember that nothing they say when they’re drunk is what they mean when they’re sober—I’ve been all through that; arrange with one of the servants that you can call on him, because you never can tell—some alcoholics are pleasant and some of them are not, but all of them can be rotten.”

“I’ll remember,” the nurse said.

It was an oddly clear night when she went out, with slanting particles of thin sleet making white of a blue-black sky. The bus was the same that had taken her into town, but there seemed to be more windows broken now and the bus driver was irritated and talked about what terrible things he would do if he caught any kids. She knew he was just talking about the annoyance in general, just as she had been thinking about the annoyance of an alcoholic. When she came up to the suite and found him all helpless and distraught she would despise him and be sorry for him.

Getting off the bus, she went down the long steps to the hotel, feeling a little exalted by the chill in the air. She was going to take care of him because nobody else would, and because the best people of her profession had been interested in taking care of the cases that nobody else wanted.

She knocked at his study door, knowing just what she was going to say.

He answered it himself. He was in dinner clothes even to a derby hat—but minus his studs and tie.

“Oh, hello,” he said casually. “Glad you’re back. I woke up a while ago and decided I’d go out. Did you get a night nurse?”

“I’m the night nurse too,” she said. “I decided to stay on twenty-four hour duty.”

He broke into a genial, indifferent smile.

“I saw you were gone, but something told me you’d come back. Please find my studs. They ought to be either in a little tortoise-shell box or—”

He shook himself a little more into his clothes, and hoisted the cuffs up inside his coat sleeves.

“I thought you had quit me,” he said casually.

“I thought I had, too.”

“If you look on that table,” he said, “you’ll find a whole strip of cartoons that I drew you.”

“Who are you going to see?” she asked.

“It’s the President’s secretary,” he said. “I had an awful time trying to get ready. I was about to give up when you came in. Will you order me some sherry?”

“One glass,” she agreed wearily.

From the bathroom he called presently:

“Oh, Nurse, Nurse, Light of my Life, where is another stud?”

“I’ll put it in.”

In the bathroom she saw the pallor and the fever on his face and smelled the mixed peppermint and gin on his breath.

“You’ll come up soon ?” she asked. “Dr Carter’s coming at ten.”

“What nonsense! You’re coming down with me.”

“Me?” she exclaimed. “In a sweater and skirt ? Imagine!”

“Then I won’t go.”

“All right then, go to bed. That’s where you belong anyhow. Can’t you see these people to-morrow?”

“No, of course not!”

She went behind him and reaching over his shoulder tied his tie—his shirt was already thumbed out of press where he had put in the studs, and she suggested:

“Won’t you put on another one, if you’ve got to meet some people you like?”

“All right, but I want to do it myself.”

“Why can’t you let me help you?” she demanded in exasperation. “Why can’t you let me help you with your clothes ? What’s a nurse for—what good am I doing?”

He sat down suddenly on the toilet seat.

“All right—go on.”

“Now don’t grab my wrist,” she said, and then, “Excuse me.”

“Don’t worry. It didn’t hurt. You’ll see in a minute.”

She had the coat, vest and stiff shirt off him but before she could pull his undershirt over his head he dragged at his cigarette, delaying her.

“Now watch this,” he said. “One—two—three.”

She pulled up the undershirt; simultaneously he thrust the crimson-grey point of the cigarette like a dagger against his heart. It crushed out against a copper plate on his left rib about the size of a silver dollar, and he said “Ouch!” as a stray spark fluttered down against his stomach.

Now was the time to be hard-boiled, she thought. She knew there were three medals from the war in his jewel box, but she had risked many things herself: tuberculosis among them and one time something worse, though she had not known it and had never quite forgiven the doctor for not telling her.

“You’ve had a hard time with that, I guess,” she said lightly as she sponged him. “Won’t it ever heal?”

“Never. That’s a copper plate.”

“Well, it’s no excuse for what you’re doing to yourself.”

He bent his great brown eyes on her, shrewd—aloof, confused. He signalled to her, in one second, his Will to Die, and for all her training and experience she knew she could never do anything constructive with him. He stood up,steadying himself on the wash-basin and fixing his eyes on some place just ahead.

“Now, if I’m going to stay here you’re not going to get at that liquor,” she said.

Suddenly she knew he wasn’t looking for that. He was looking at the corner where he had thrown the bottle the night before. She stared at his handsome face, weak and defiant—afraid to turn even halfway because she knew that death was in that corner where he was looking. She knew death—she had heard it, smelt its unmistakable odour, but she had never seen it before it entered into anyone, and she knew this man saw it in the corner of his bathroom; that it was standing there looking at him while he spat from a feeble cough and rubbed the result into the braid of his trousers. It shone there crackling for a moment as evidence of the last gesture he ever made.

She tried to express it next day to Mrs Hixson:

“It’s not like anything you can beat—no matter how hard you try. This one could have twisted my wrists until he strained them and that wouldn’t matter so much to me. It’s just that you can’t really help them and it’s so discouraging—it’s all for nothing.”

Published in Esquire magazine (February 1937).

Illustrations by George Grosz.