Selected Letters

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

It is to be hoped that Scott Fitzgerald’s letters will be eventually collected and published. Those that follow are merely a handful that happened to be easily obtainable and which throw light on Fitzgerald’s literary activities and interests. The first group consists of letters to friends; the second of letters to his daughter. In most of the letters of the first group, the spelling and punctuation have been left as they were in the originals, except for the uniform italicization of titles of books and magazines and the insertion of missing ends of parentheses.

1913

To Elizabeth Craig Clarkson [St. Paul, Minn: September 15, 1913].

Dear Litz:

I write to tell you how very sorry I was that I couldnt accept your “invite” yesterday. But bronchitis interposed its highly annoying hand and spoiled it. Remember, Litz, until we meet “when the Holly blooms” in three months you are “She who (quick somebody, give me [?] an appropriate [crossed-out word] quatushun [sic]) well anyway [crossed out word] you are she who. I am in a particularly despondent and dissipated mood. Outside the sun is shining but I am perfectly positive it is only doing it out of spite. In the church across the way they are singing hymns. I think they might be at least sing (Hers) [?] I am going to write you at Miss Hartridges School, Plainsfield N.J. and I swear it will be a sensible letter not a foolish jumble like this for

My mind is all a-tumble

And the letter seems a jumble

for the words they seem to mumble

And my pens about to stumble

and the papers made to jumble

So I sign myself your humble

Servant

Francis Scott Fitzgerald

P.S. My query of “Have you no compunctions” is still unanswered. Any time you have compunctions or any other discease [sic] send me a night letter—

(signed) Scott—

To Elizabeth Craig Clarkson, 15 University Park, Princeton, N. J.: Sept. 26th, 1913.

Dear Elizabeth:

Nunc Sum Studens. (Latin.) I am now a Princetonian. Its great. Im crazy about it. Today we had the rushes. The Sophs mass in a body in front of the gym and the Freshmen try to rush their way in. You can imagine it. Four hundred Freshmen, among them yours truly, against 380 Sophs. Everything was ruined shirts, jerseys, shoes, socks, trou, hats ect. were strewn over the battle-field. I was completely done up. I was in the front row and a soph and I almost killed each other. I am a mass of bruises from head to foot. When we got in we elected a class President, Vice Pres. and sec. When we came out again the sophs. tried to bust our line. We beat H——— out of them. Then we paraded around the campus, yelling “whoop it up for seventeen,” which is a wonderful song. Then we cheered and sang. Zip!!! This is some place. I have a big piece of some sophs shirt. Somebody has a big piece of my jersey. (Lord only knows who.) Tonight is the cannon rush so if you never hear from me again youll know I died a freshman.(gentle pathos.) The “horsing” (or hazing) is going on now. Its very foolish. Freshies have to carry their cap in their mouths and by the way our uniforms are some class (not)

[Here, Fitzgerald has drawn a humorous image of himself as a Freshman in uniform].

(Picture of me in my Freshman uniform)

Black cap --->

Black jersey --->

Cordoroy [sic] Trou --->

Black socks --->

Black shoes --->

The Sophs. make you tell a funny story and then wont laugh but tell you to finish. Then they tell you to dig for the point. (N.B. You dig) This morning I gave.

1917

TO EDMUND WILSON September 26th, 1917 593 Summit Ave St. Paul, Minn.

Dear Bunny:

You’ll be surprised to get this but it’s really begging for an answer. My purpose is to see exactly what effect the war at close quarters has on a person of your temperament. I mean I’m curious to see how you’re point of view has changed or not changed—

I’ve taken regular army exams but haven’t heard a word from them yet. John Bishop is in the second camp at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana. He expects a 1st Lieutenancy. I spent a literary month with him (July) and wrote a terrific lot of poetry mostly under the Masefield-Brooke influence.

Here’s John’s latest.

BOUDOIR

The place still speaks of worn-out beauty of roses,

And half retrieves a failure of Bergamotte,

Rich light and a silence so rich one all but supposes

The voice of the clavichord stirs to a dead gavotte

For the light grows soft and the silence forever quavers,

As if it would fail in a measure of satin and lace,

Some eighteenth century madness that sighs and wavers

Through a life exquisitely vain to a dying grace.

This was the music she loved; we heard her often

Walking alone in the green-clipped garden outside.

It was just at the time when summer begins to soften

And the locust shrills in the long afternoon that she died.

The gaudy macaw still climbs in the folds of the curtain;

The chintz-flowers fade where the late sun strikes them aslant.

Here are her books too: Pope and the earlier Burton,

A worn Verlaine; Bonheur and the Fetes Galantes.

Come—let us go—I am done. Here one recovers

Too much of the past but fails at the last to find

Aught that made it the season of loves and lovers;

Give me your hand—she was lovely—mine eyes blind.

Isn’t that good? He hasn’t published it yet. I sent twelve poems to magazines yesterday. If I get them all back I’m going to give up poetry and turn to prose. John may publish a book of verse in the Spring. I’d like to but of course there’s no chance. Here’s one of mine.

To CECILIA

When Vanity kissed Vanity

A hundred happy Junes ago,

He pondered o’er her breathlessly,

And that all time might ever know

He rhymed her over life and death,

“For once, for all, for love,” he said…

Her beauty’s scattered with his breath

And with her lovers she was dead.

Ever his wit and not her eyes,

Ever his art and not her hair.

“Who’d learn a trick in rhyme be wise

And pause before his sonnet there.“

So all my words however true

Might sing you to a thousandth June

And no one ever know that you

Were beauty for an afternoon.

It’s pretty good but of course fades right out before John’s. By the way I struck a novel that you’d like Out of Due Time by Mrs. Wilfred Ward. I don’t suppose this is the due time to tell you that, though. I think that The New Machiavelli is the greatest English novel of the century. I’ve given up the summer to drinking (gin) and philosophy (James and Shoepenhaur and Bergson).

Most of the time I’ve been bored to death—Wasn’t it tragic about Jack Newlin—I hardly knew poor Gaily . Do write me the details.

I almost went to Russia on a commission in August but didn’t so I’m sending you one of my passport pictures—if the censor doesn’t remove it for some reason—It looks rather Teutonic but I can prove myself a Celt by signing myself

Very sincerely

F. Scott Fitzgerald

TO EDMUND WILSON [Autumn of 1917] Cottage Club, Princeton, N. J.

Dear Bunny:

I’ve been intending to write you before but as you see I’ve had a change of scene and the necessary travail there-off has stolen time.

Your poem came to John Biggs, my room-mate, and we’ll put it in the next number—however it was practically illegible so I’m sending you my copy (hazarded) which you’ll kindly correct and send back—

I’m here starting my senior year and still waiting for my commission. I’ll send you the Litt. or no—you’ve subscribed haven’t you…

Do write John Bishop and tell him not to call his book Green Fruit.

Alec is an ensign. I’m enclosing you a clever letter from Townsend Martin which I wish you’d send back.

Princeton is stupid but Gauss and Gerrould are here. I’m taking naught but Philosophy&English—I told Gauss you’d sailed (I’d heard as much) but I’ll contradict the rumor.

Have you read Well’s Boon, the Mind of the Race, (Doran —1916) It’s marvellous! (Debutante expression.)

The Litt is prosperous—Biggs&I do the prose—Creese and Keller (a junior who’ll be chairman) and I the poetry. However any contributions would be ect. ect.

Young Benet (at New Haven) is getting out a book of verse before Xmas that I fear will obscure John Peale’s. His subjects are less precieuse&decadent. John is really an anachronism in this country at this time—people want ideas and not fabrics.

I’m rather bored here but I see Shane Leslie occasionally and read Wells and Rousseau. I read Mrs. Geroulds British Novelists Limited&think she underestimates Wells but is right in putting McKenzie at the head of his school. She seems to disregard Barry and Chesterton whom I should put above Bennet or in fact anyone except Wells.

Do you realize that Shaw is 61, Wells 51, Chesterton 41, Leslie 31 and I 21. (Too bad I haven’t a better man for 31. I can hear your addition to this remark)…

Yes—Jack Newlin is dead—killed in ambulance service. He was, potentially, a great artist.

Here is a poem I just had accepted by Poet Lore

THE WAY OF PURGATION

A fathom deep in sleep I lie

With old desires, restrained before;

To clamor life-ward with a cry

As dark flies out the greying door.

And so in quest of creeds to share

I seek assertive day again;

But old monotony is there—

Long, long avenues of rain.

Oh might I rise again! Might I

Throw off the throbs of that old wine—

See the new morning mass the sky

With fairy towers, line on line—

Find each mirage in the high air

A symbol, not a dream again!

But old monotony is there—

Long, long avenues of rain.

No—I have no more stuff of Johns—I ask but never receive.

[News jottings (unofficial)] If Hillquit gets the mayoralty of New York it means a new era. Twenty million Russians from South Russia have come over to the Roman Church.

I can go to Italy if I like as private secretary of a man (a priest) who is going as Cardinal Gibbons representative to discuss the war with the Pope (American Catholic point of view—which is most loyal—barring the Sien-Fien—40% of Pershing’s army are Irish Catholics). Do write.

Gaelicly yours

Scott Fitzgerald

I remind myself lately of Pendennis, Sentimental Tommy (who was not sentimental and whom Barrie never understood) Michael Fane, Maurice Avery&Guy Hazelwood .

1918

Jan 1918. J. P. Bishop

Bishop wrote ...even death there would be a compensation - Keats, Shelley, Browning, Wilde, Bishop various and gifted quintet, let us weep over all five...

And Fitzgerald responded:

TO EDMUND WILSON Jan. 10th, 1917 [1918]

Dear Bunny:

Your last refuge from the cool sophistries of the shattered world, is destroyed! I have left Princeton. I am now Lieutenant F. Scott Fitzgerald of the 45th Infantry (regulars). My present address is

co Q.P.O.B.

Ft. Leavenworth

Kan.

After Feb 26th

593 Summit Ave.

St. Paul

Minnesota

will always find me forwarded.

—So the short, swift chain of the Princeton intellectuals, Brooke’s clothes, clean ears and, withall, a lack of mental prigishness … Whipple, Wilson, Bishop, Fitzgerald … have passed along the path of the generation—leaving their shining crown upon the gloss and unworthiness of John Bigg’s head.

One of your poems I sent on to the Litt. and I’ll send the other when I’ve read it again. I wonder if you ever got the Litt. I sent you… So I enclosed you two pictures , well give one to some poor motherless Poilu fairy who has no dream. This is smutty and forced but in an atmosphere of cabbage…

John’s book came out in December and though I’ve written him rheams (Rhiems) of praise, I think he’s made poor use of his material. It is a thin Green Book.

GREEN FRUIT

by JOHN PEALE BISHOP

1st Lt. Inf. R.C.

SHERMAN FRENCH CO.

BOSTON

In section one (Souls and Fabrics) are Boudoir, The Nassau Inn and of all things Fillipo’s Wife, a relic of his decadent sophomore days. Claudius and other documents in obscurity adorn this section.

Section two contains the Elspeth poems—which I think are rotten. Section three is Poems out of Jersey and Virginia and has Campbell Hall, Millville and much sacharine sentiment about how much white bodies pleased him and how, nevertheless, he was about to take his turn with crushed brains (this slender thought done over in poem after poem). This is my confidential opinion, however; if he knew what a nut I considered him for leaving out Ganymede and Salem Water and Francis Thompson and Prayer and all the things that might have given body to his work, he’d drop me from his writing list. The book closed with the dedication to Townsend Martin which is on the circular I enclose. I have seen no reviews of it yet.

***

THE ROMANTIC EGOTIST

by F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

“… the Best is over

You may complain and sigh

Oh Silly Lover…”

Rupert Brooke

“Experience is the name Tubby gives to his mistakes.”

Oscar Wilde

Chas. Scribners Sons (Maybe!)

MCMXVIII

***

There are twenty-three chapters, all but five are written and it is poetry, prose, vers libre and every mood of a temperamental temperature. It purports to be the picaresque ramble of one Stephen Palms [Dalius?] from the San Francisco fire thru school, Princeton, to the end where at twenty-one he writes his autobiography at the Princeton aviation school. It shows traces of Tarkington, Chesterton, Chambers, Wells, Benson (Robert Hugh), Rupert Brooke and includes Compton-McKenzielike love-affairs and three psychic adventures including an encounter with the devil in a harlot’s apartment.

It rather damns much of Princeton but its nothing to what it thinks of men and human nature in general. I can most nearly describe it by calling it a prose, modernistic Childe Harolde and really if Scribner takes it I know I’ll wake some morning and find that the debutantes have made me famous over night. I really believe that no one else could have written so searchingly the story of the youth of our generation.

In my right hand bunk sleeps the editor of Contemporary Verse (ex) Devereux Joseph, Harvard ’15 and a peach—on my left side is G. C. King a Harvard crazy man who is dramatizing War and Peace; but you see I’m lucky in being well protected from the Philistines.

The Litt continues slowly but I haven’t received the December issue yet so I cant pronounce on the quality.

This insolent war has carried off Stuart Wolcott in France, as you may know and really is beginning to irritate me—but the maudlin sentiment of most people is still the spear in my side. In everything except my romantic Chestertonian orthodoxy I still agree with the early Wells on human nature and the “no hope for Tono Bungay” theory.

God! How I miss my youth—that’s only relative of course but already lines are beginning to coarsen in other people and that’s the sure sign. I don’t think you ever realized at Princeton the childlike simplicity that lay behind all my petty sophistication and my lack of a real sense of honor. I’d be a wicked man if it wasn’t for that and now that’s disappearing.

Well I’m overstepping and boring you and using up my novel’s material. So Goodbye. Do write and lets keep in touch if you like.

God bless you.

Celticly

F.Scott Fitzgerald

Bishop’s adress

Lieut. John Peale Bishop (He’s a 1st Lt.)

334th Infantry

Camp Taylor

Kentucky

1919

From Zelda Sayre, Spring 1919

Sweetheart,

Please, please don’t be so depressed—We’ll be married soon, and then these lonesome nights will be over forever—and until we are, I am loving, loving every tiny minute of the day and night—Maybe you won’t understand this, but sometimes when I miss you most, it’s hardest to write—and you always know when I make myself—Just the ache of it all—and I can’t tell you. If we were together, you’d feel how strong it is—you’re so sweet when you’re melancholy. I love your sad tenderness—when I’ve hurt you—That’s one of the reasons I could never be sorry for our quarrels—and they bothered you so—Those dear, dear little fusses, when I always tried so hard to make you kiss and forget—

Scott—there’s nothing in all the world I want but you—and your precious love—All the materials things are nothing. I’d just hate to live a sordid, colorless existence-because you’d soon love me less—and less—and I’d do anything—anything—to keep your heart for my own—I don’t want to live—I want to love first, and live incidentally…Don’t—don’t ever think of the things you can’t give me—You’ve trusted me with the dearest heart of all—and it’s so damn much more than anybody else in all the world has ever had—

How can you think deliberately of life without me—If you should die—O Darling—darling Scott—It’d be like going blind…I’d have no purpose in life—just a pretty—decoration. Don’t you think I was made for you? I feel like you had me ordered—and I was delivered to you—to be worn—I want you to wear me, like a watch—charm or a button hole bouquet—to the world. And then, when we’re alone, I want to help—to know that you can’t do anything without me…

All my heart—

I love you

1920

TO EDMUND WILSON [1920] 599 Summit Ave. St. Paul, Minn August 15th

Dear Bunny:

Delighted to get your letter. I am deep in the throes of a new novel.

Which is the best title

(1) The Education of a Personage

(2) The Romantic Egotist

(3) This Side of Paradise

I am sending it to Scribner. They liked my first one. Am enclosing two letters from them that might amuse you. Please return them.

I have just finished the story for your book. It’s not written yet. An American girl falls in love with an officer Francais at a southern camp.

Since I last saw you I’ve tried to get married&then tried to drink myself to death but foiled, as have been so many good men, by the sex and the state I have returned to literature.

Have sold three or four cheap stories to American magazines.

Will start on story for you about 25th d’Auout (as the French say or do not say) (which is about 10 days off)

I am ashamed to say that my Catholicism is scarcely more than a memory—no that’s wrong it’s more than that; at any rate I go not to the church nor mumble stray nothings over chrystaline beads.

Maybe in N’York in Sept or early Oct.

Is John Bishop in hoc terrain?…

For God’s sake Bunny write a novel&don’t waste your time editing collections. It’ll get to be a habit.

That sounds crass&discordant but you know what I mean.

Yours in the Holder group

Scott Fitzgerald

TO EDMUND WILSON [1920] 599 Summit Ave. St. Paul, Minn.

Dear Bunny:

Scribner has accepted my book for publication late in the winter. You’ll call it sensational but it really is niether sentimental nor trashy.

I’ll probably be East in November&I’ll call you up or come to see you or something. Haven’t had time to hit a story for you yet. Better not count on me as the w. of i. or the E.S. are rather dry.

Yrs. faithfully

Francis S. Fitzgerald

To Carl Hovey

Westport, Conn. Aug 12th 1920

Dear Mr. Hovey:

I want to ask you a question. How long would it take to seriazize a 120,000 word novel? My plans have changed, I think. Here is new project.

(1) “Flappers + Philosophers” my 1st collection of short stories to appear in Oct.

(2) A second collection of short stories to appear next Spring + to include the Jellybean, three little plays and also four stories not yet written.

(3) My new novel in which I am deeply absorbed “The Flight of the Rocket” to appear next autumn.

Let us suppose you get the novel in Nov., like it + begin to serialze it in January or February. Then how about these three or four stories I intend to write when I finish the novel + which should be published before spring to be eligible for the collection. Could you publish them simultaeneously? Would you prefer only the novel? Would you prefer only the short stories?

Of course the easiest way would be for me to do the short stories 1st but its utterly impossible as I’m plunged in the middle of the novel + wouldn’t leave it for $10,000.

The only solution it seems to me is for me to rewrite a fairly good novelette which appeared in the June Smart Set instead of the new short stories + publish it in the spring collection. Then I would devote the time between finishing my novel in Nov. and going abroad in Jan. to this revising and to writing a play which I’ve always wanted to do.

Let me hear from you. Went over to Miss Rita Willmans + I think she’s a very striking personality + most attractive

Sincerely

F Scott Fitzgerald

To Carl Hovey

38 W. 59th St. New York City

Dear Mr. Hovey:

Am about half thru my novel but went down to the bank last week + found my account so distressingly not to say so alarmingly low that I had to do a short story at once.

I hope you’ll like it. I think its the best thing I’ve ever done.

Sincerely

F Scott Fitzgerald

To Carl Hovey

Oct 27th, 1920 38 W. 59th St.

Dear Mr. Hovey:

About the story. Glad you like it + I’ll admit it’ll be over the heads of a few people. I solemnly promise that the next one I send will be as jazzy + popular as The Offshore Pirate to make up for it.

As you can see the girl, of course, represents that inhibited attraction that all men show to a “wild + beautiful woman". The greyer a mans life is the more it comes out. But if I’d have explained the story in anyway but a dream it would have been a regular Max Beerbohm extravaganza + hence furthur over people’s heads that it is now. But I do think to come out + say “it was all a dream” in so many words would cheapen + rather spoil the story.

Sincerely

F Scott Fitzgerald

1921

To Carl Hovey

Fri, April 22nd 1921 38 W. 59th Street

Dear Mr. Hovey:

I’m sending you today, through Reynolds, the first of the three parts of The Beautiful and Damned. The second part should reach you Monday and the third part Tuesday.

After the ten months I have been working on it it has turned out as I expected—and rather dreaded—a bitter and insolent book that I fear will never be popular and that will undoubtedly offend a lot of people. Personally, I should advise you against serializing it— now that the damn thing is off my hand I can try a few cheerful stories. If you do not want it, I don’t believe I shall offer it to anyone else but shall let Scribners bring it out in September—which is probably the psychological time anyhow.

On May 3d Zelda and I are going abroad for a few months (and I expect to write several movies and short stories while I’m over) so I’m sending you the thing in parts that I may get as early a decision as possible. Could you let me know, do you think, by Saturday the thirtieth? You see if you don’t serialize it I shall have to depend on an advance from Scribner for our trip and of course I can’t ask for that until I hear from you.

My best to Mrs Hovey

Sincerely

F Scott Fitzgerald

To Carl Hovey

June 25th, 1921

Dear Mr Hovey:

What you say about the book fell sweetly on my ear. This Side of Paradise is having a checkered career in England. I’m not sure yet whether its going to be a sucess or not.

We spent a month in Italy + had a rotten time. We’re coming to America early in July and I’m curious to see what you’ve done with the novel. Perhaps some of your cutting away may give excellent suggestion for further pruning of the book section.

Zelda and I feel you’ve made a grave mistake about the illustrator. This Benson did one of my stories in the Post + My God! you ought to see the grey blurs he made of my beautiful protagonists. But perhaps he’ll rise to the occasion. My best to Mrs. Hovey.

As Ever

F Scott Fitzgerald

TO JOHN V. A. WEAVER [1921] 626 Goodrich Ave. St. Paul, Minn

Dear John:

I was tickled to write the review . I saw Broun’s&F.P.A.’s reviews but you know how they love me&how much attention I pay to their dictums.

This is my new style of letter writing . It is to make it easy for comments¬es to be put in when my biographer begins to assemble my collected letters.

The Metropolitan isn’t here yet. I shall certainly read Enamel. I wish to Christ I could go to Europe.

Thine

F.Scott Fitzgerald

TO EDMUND WILSON [Postmarked November 25, 1921] 626 Goodrich Avenue St. Paul, Minn.

Dear Bunny:

Thank you for your congratulations. I’m glad the damn thing’s over. Zelda came through without a scratch&I have awarded her the croix-de-guerre with palm. Speaking of France, the great general with the suggestive name is in town today.

I agree with you about Mencken—Weaver&Dell are both something awful...

I have almost completely rewritten my book. Do you remember you told me that in my midnight symposium scene I had sort of set the stage for a play that never came off—in other words when they all began to talk none of them had anything important to say. I’ve interpolated some recent ideas of my own and (possibly) of others. See inclosure at end of letter … Having disposed of myself I turn to you. I am glad you and Ted Paramore are together… I like Ted immensely. He is a little too much the successful Eli to live comfortably in his mind’s bed-chamber but I like him immensely.

What in hell does this mean? My control must have dictated it. His name is Mr. Ikki and he is an Alaskan orange-grower…

If the baby is ugly she can retire into the shelter of her full name Frances Scott.

St. Paul is dull as hell. Have written two good short stories and three cheap ones.

I like Three Soldiers immensely&reviewed it for the St. Paul Daily News. I am tired of modern novels&have just finished Paine’s biography of Clemens. It’s excellent. Do let me see if you do me for the Bookman. Isn’t The Triumph of the Egg a wonderful title. I liked both John’s and Don’s articles in Smart Set. I am lonesome for N. Y. May get there next fall&may go to England to live. Yours in this hell-hole of life&time, the world.

F. Scott Fitz

1922

To Carl Hovey

ZELDA SAYRE FITZGERALD

Dear Mr. Hovey—

I am very ashamed of myself—but you know how it is to be a drinking woman! Here is this foolish thing and I hope it will be something like what you wanted. “The Flapper” is a very difficut subject for me because I cherish a secret ambition of being one someday—and take the cuties quite seriously.

We enjoyed seeing you in New York, and thanks again for the slick party.

Sincerely,

Zelda Fitz—

Would the end of the week be too late for the picture? And could you let me know if you are in a hurry. And will Mrs Hovey come thru here on her way East?

To Sonia Hovey

Sonia!

Sorry as hell I missed you! Studio all day + just in, to find your note. Wept at thought of your taking walk alone.

Tomorrow one of those smoky orgies known as conferences but will phone you then + we’ll arrange lunch or dinner or perhaps I’ll give my fete this week Sent Carl the letter.

Bought the car—Kaiser was fine. I had the jitters about traffic + he was very patient

Till Soon Your Chattel Scott Fitz

To Carl Hovey

Dear Carl and Sonya:

Feel like a bitch leaving you with sickness and not saying goodbye. The last days crept up on us like telegraph poles on the Broadway limited with work still to do and people and the Barlycorns which are to Hollywood what the Smiths are to the English speaking world.

Zelda sends long nuptial kisses. The black shape above is my heart.

Scott

The mss were of enormous help.

TO EDMUND WILSON [Postmarked January 24, 1922] 626 Goodrich Ave. St. Paul, Minn.

Dear Bunny:

Farrar tells a man here that I’m to be in the March Literary Spotlight. I deduce that this is your doing. My curiosity is at fever heat—for God’s sake send me a copy immediately.

Have you read Upton Sinclair’s The Brass Check?

Have you seen Hergeshiemer’s movie Tol’able David?

Both are excellent. I have written two wonderful stories&get letters of praise from six editors with the addenda that “our readers, however, would be offended.” Very discouraging. Also discouraging that Knopf has put off the Garland till fall. I enjoyed your da-daist article in Vanity Fair—also the free advertising Bishop gave us. Zelda says the picture of you is “beautiful and bloodless.”

I am bored as hell out here. The baby is well—we dazzle her exquisite eyes with gold pieces in the hopes that she’ll marry a millionaire. We’ll be east for ten days early in March…

What are you doing? I was tremendously interested by all the data in your last letter. I am dying of a sort of emotional aenemia like the lady in Pound’s poem. The Briary Bush is stinko.

Cytherea is Hergeshiemer’s best but its not quite.

Yours

John Grier Hibben

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [Probably written in the spring of 1922] 626 Goodrich Avenue [St. Paul, Minn.]

Dear John:

I’ll tell you frankly what I’d rather you’d do. Tell specifically what you like about the book and don’t——. The

characters—Anthony, Gloria, Adam Patch, Maury, Bleekman, Muriel Dick, Rachael, Tana ect ect ect. Exactly whether they are good or bad, convincing or not. What you think of the style, too ornate (if so quote) good (also quote) rotten (also quote). What emotion (if any) the book gave you. What you think of its humor. What you think of its ideas. If ideas are bogus hold them up specifically and laugh at them. Is it boring or interesting. How interesting. What recent American books are more so. If you think my “Flash Back in Paradise” in Chap I is like the elevated moments of D.W. Griffith say so. Also do you think it is imitative and of whom.

What I’m angling for is a specific definite review. I’m tickled both that they have asked for such a lengthy thing and that you are going to do it. You cannot hurt my feelings about the book—tho I did resent in your Baltimore article being definitely limited at 25 years old to a place between McKenzie who wrote 2 1/2 good (but not wonderful) novels and then died—and Tarkington who if he has any talent has the mind of a schoolboy. I mean, at my age, they’d done nothing.

As I say I’m delighted that you’re going to do it and as you wrote asking me to suggest a general mode of attack I am telling you frankly what I would like. I’m so afraid of all the reviews being general and I devoted so much more care myself to the detail of the book than I did to thinking out the general scheme that I would appreciate a detailed review. If it is to be that length article it could scarcely be all general anyway.

I’m awfully sorry you’ve had the flue. We arrive east on the 9th. I enjoy your book page in Vanity Fair and think it is excellent—

The baby is beautiful.

As Ever

Scott

TO EDMUND WILSON [Probably written in the spring of 1922] 626 Goodrich Ave. St. Paul, Minn.

Dear Bunny:

From your silence I deduce that either you decided that the play was not in shape to offer to the Guild or that they refused it.

I have now finished the revision. I am forwarding one copy to Harris &, if you think the Guild would be interested, will forward them the other. Your play should be well along by now. Could you manage to send me a carbon?

I’m working like a dog on some movies at present. I was sorry our meetings in New York were so fragmentary. My original plan was to contrive to have long discourses with you but that interminable party began and I couldn’t seem to get sober enough to be able to tolerate being sober. In fact the whole trip was largely a failure.

My compliments to Mary Blair, Ted Paramour and whomsoever else of the elect may cross your path.

We have no plans for the summer.

Scott Fitz—

TO EDMUND WILSON June 25th, 1922

Dear Bunny:

Thank you for giving the play to Craven—and again for your interest in it in general. I’m afraid I think you overestimate it—because I have just been fixing up Mr. Icky for my fall book and it does not seem very good to me. I am about to start a revision of the play—also to find a name. I’ll send it to Hopkins next. So far it has only been to Miller, Harris&the Theatre Guild. I’d give anything if Craven would play that part. I wrote it, as the text says, with him in mind. I agree with you that Anna Christie was vastly overestimated…

Am going to write another play whatever becomes of this one. The Beautiful&Damned has had a very satisfactory but not inspiring sale. We thought it’d go far beyond Paradise but it hasn’t. It was a dire mistake to serialize it. Three Soldiers and Cytherea took the edge off it by the time it was published…

Did you like The Diamond as Big as the Ritz or did you read it. It’s in my new book anyhow…

I have Ullyses from the Brick Row Bookshop&am starting it. I wish it was layed in America—there is something about middle-class Ireland that depresses me inordinately— I mean gives me a sort of hollow, cheerless pain. Half of my ancestors came from just such an Irish strata or perhaps a lower one. The book makes me feel appallingly naked. Expect to go either South or to New York in October for the Winter.

Ever thine,

F. Scott Fitz

TO EDMUND WILSON [Postmarked August 1, 1922] The Yatch Club White Bear Lake, Minn.

Dear Bunny:

Just a line to tell you I’ve finished my play&am sending it to Nathan to give to Hopkins or Selwyn. It is now a wonder. I’m going to ask you to destroy the 2 copies you have as it makes me sort of nervous to have them out. This is silly but so long as a play is in an actors office and is unpublished as my play at Cravens I feel lines from it will soon begin to appear on B’way…

Write me any gossip if you have time. No news or plans have I.

Thine

Fitz

TO EDMUND WILSON F. Scott Fitzgerald Hack Writer and Plagiarist St. Paul Minnesota [Postmarked August 5, 1922]

Dear Bunny:

Fitzgerald howled over Quintilian. He is glad it was reprinted as he couldn’t get the Double Dealer and feared he had missed it. It’s excellent especially the line about Nero and the one about Dr. Bishop.

The play with an absolutely new second act has gone to Nathan who is giving it to Hopkins or Selwynn. Thank you for taking it to Ames&Elkins. I’m rather glad now that none of them took it as I’d have been tempted to let them do it—and my new version is much better. Please do not bother to return the 2 mss. you have as its a lot of trouble. I have copies of them&no use for them. Destruction will save the same purpose—it only worries me to have them knocking around.

I read sprigs of the old oak that grew from the marriage of Mencken&Margaret Anderson (Christ! What a metaphor!) and is known as the younger genitals. It bored me. I didn’t read yours—but * * * * is getting worse than Frank Harris with his elaborate explanations and whitewashings of himself. There’s no easier way for a clever writer to become a bore. It turns the gentle art of making enemies into the East Aurora Craft of making people indifferent … in the stunned pause that preceded this epigram Fitzgerald bolted his aspic and went to a sailor’s den.

“See here,” he said, “I want some new way of using the great Conradian vitality, the legend that the sea exists without Polish eyes to see it. Masefield has spread it on iambics and downed it; O’Niell has sprinkled it on Broadway; McFee has added an evenrude motor—”

[cribbed from Harry-Leon Wilson] But I could think of no new art form in which to fit him. So I decided to end the letter. The little woman, my best pal and I may add, my severest critic, asked to be remembered.

Would you like to see the new play? Or are you fed up for awhile. Perhaps we better wait till it appears. I think I’ll try to serialize it in Scribners—would you?

Scott F.

Am undecided about Ullyses application to me—which is as near as I ever come to forming an impersonal judgement.

TO EDMUND WILSON [Postmarked August 28, 1922] The Yatch Club White Bear Lake Minnesota

Dear Bunny—

The Garland arrived and I have re-read it. Your preface is perfect—my only regret is that it wasn’t published when it was written almost two years ago. The Soldier of course I read for about the fifth time. I think it’s about the best short war story yet—but I object violently to “pitched forward” in the lunch-putting anecdote. The man would have said “fell down” or “sorta sank down.” Also I was delighted as usual by the Efficiency Expert. Your poems I like less than your prose—The Lake I do not particularly care for. I like the Centaur and the Epilogue best—but all your poetry seems to flow from some source outside or before the romantic movement even when its intent is most lyrical.

I like all of John’s except the play which strikes me as being obvious and Resurrection which despite its excellent idea&title&some spots of good writing is pale and without any particular vitality.

Due to you, I suppose, I had a wire from Langner. I referred him to Geo. Nathan.

Many thinks for the book. Would you like me to review it? If so suggest a paper or magazine and I’ll be glad to.

Thine

F. Scott Fitz.

The format of the book is most attractive. I grow envious every time I see a Knopf binding.

To Tom Boyd, 1922

This handwritten letter is one page written in soft, dark pencil on a piece of newsprint when Scott and Tom Boyd were colleagues on the St. Paul Daily News. In addition to being a book reviewer, Boyd also had a bookshop, Kilmarnock Books. Dimensions; 7" x 6.5". Signed boldly by "F. Scott Fitzgerald." Detailed letter of provenance available.

Dear Boyd, It seems to me that that was a rather ill-advised interview Sunday. Should it come to the attention of the Metropolitan it is apparent that all friendly relations between Hovey and myself should (crossed out) would cease. I thought you understood that a popular magazine reserves the rights to make changes--you see it would be bad business for me to criticize them publicly for making changes that they have bought the right to make.I trust that clause of it won t appear elsewhere. Sincerely,B. FScott Fitzgerald

After serving in World War I as a Marine, Boyd received the Croix de Guerre and wrote his magnum opus, Through the Wheat. Thomas Boyd married Margaret Smith and they settled in Saint Paul. There he worked as a journalist at The St. Paul Daily News and ran Kilmarnock Books, where he entertained the likes of Aldous Huxley, Sinclair Lewis, Edna Ferber, Theodore Dreiser, and other literary luminaries, interviewing them and writing reviews of their current novels. Boyd and Fitzgerald were close friends for a time, and Fitzgerald took Boyd s manuscript of Through the Wheat to Max Perkins and urged its publication. Fitzgerald also wrote a glowing review of the novel upon its publication. The Boyds achieved enough success to leave journalism behind. Margaret (Peggy) wrote under the pseudonym of Woodward Boyd (The Love Legend). They left Minnesota in the 1920s for Connecticut where they pursued writing fiction full-time. Thomas Boyd would write several other books including Points of Honor (1925), a collection of stories, and Shadow of the Long Knives (1928), before his untimely death in 1935. (Note: See Brian Bruce's splendid biography "Thomas Boyd: Lost Author of "The Lost Generation.").

1923

To Tom Boyd, 1923

This handwritten letter is 2 pages, 8.5 " x 11" written in ink from Great Neck when Scott and Tom Boyd were friends and colleagues on the St. Paul Daily News. In addition to being a book reviewer, Boyd also had a bookshop, Kilmarnock Books. Dimensions; 8.5" x 11". Signed boldly "As ever Scott " Detailed letter of provenance upon request. Fitzgerald is referring to Boyd s first novel, Through the Wheat, and his efforts to promote it and have it reviewed by Edmund Wilson and H.L. Mencken. Fitzgerald himself wrote a very handsome review of the novel. After all, it was Fitzgerald who took the manuscript of Through the Wheat to Max Perkins at Scribner's and ardently urged its publication.

Dear Tom Thanks for the book, the pre-review and the scrumptious inscription and also for liking The Vegetable. Your book (Through the Wheat) is quite a sensation here and you certainly have to thank Perkins for the best press of the spring. As to the sale it depends on that incalculable element the public mood, the psychological state they re in. There s been so much exploitation lately that is almost impossible for a press to create a mood. However its certainly made you among the literati. I got Wilson to read it. He liked it enormously and is reviewing it. Also I sent a copy to Mencken with section of the jacket marked off (deleted) lest he get a false impression. He said of Peggy s book in his reply that it was a good substantial canny piece of work marred by some high school crudities. When she gets her royalty report in August please let me know how many it sold. I gave your name to Charlie Towne of the American Play Co. He is a first class literary agent in case either of you have any commercial short stories. Also he s a damn good man for a young writer to know I mean he goes everywhere, is enthusiastic, and talks. Best to Cornelius. I m busy as hell. Hope you ll like my reviewAs Ever, Scott

P.S. Is The Vegetable selling at all there?

1924

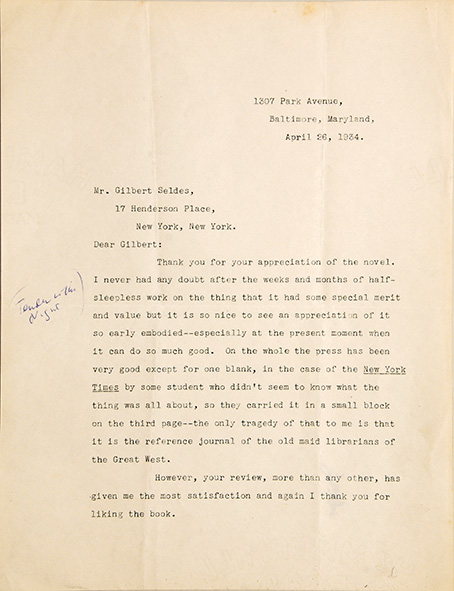

To Maxwell Perkins [1924]

This is to tell you about a young man named Ernest Hemingway who lives in Paris (an American), writes for the Transatlantic Review and has a brilliant future… I’d look him up right away. He’s the real thing.

To Miss Esther Sanford, 3449 Harlbut Ave Detroit, Michigan [postmarked Great Neck, NY, April 8, 1924]

Dear Miss Sanford:

I absolutely refuse to give you my autograph.

Sincerely,

F. Scott Fitzgerald.

To Tom Boyd, 1924-06-23

This handwritten letter is 2 pages, 8.5 " x 11" written in ink from Villa Marie, Valescure, St. Raphael, Var, France when Scott and Tom Boyd were friends and colleagues on the "St. Paul Daily News." In addition to being a book reviewer, Boyd also had a bookshop, Kilmarnock Books. Dimensions; 8.5" x 11". Signed boldly "Yours ever, F. Scott Fitz " Detailed letter of provenance upon request.

Dear Tom: Villa Marie, Valescure, St. Raphael, Var, France. June 23d, 1924 Hyere's proved too hot for summer. I loved it but the bathing was bad and we couldn't find a new clean villa. So we're up the coast between St. Maxime and Cannes in a charming villa we've got until November 1st. I saw a lot of Hyere s during the week we were there the castle on the hill I liked especially there one day I met a twelve year old girl on the street whose face had been eaten off with congenital syphilis. She had the back of her head and in front of that nothing but a scab slit three times for her mouth and eyes It rather spoiled the street for me. Anyways after seeing Cannes, Hyeres, Nice, St. Maximes, and Antibes, I think St. Raphael (where we are) is the loveliest spot I ve ever seen. It s simply saturated with Shelley tho he never lived here. I mean its like the "Euganean Hills" and "lines written in Dejection" cooler than Hyeres, less tropical, less somnolent, perhaps less Romanesque still Frejus which has aqueducts and is both Roman and Romanesque is in sight of my window. We have bought a little Reynault car and Zelda and the baby and the Governess swim every day on a sandy beach in fact everything s idyllic and for the first time since I went to St. Paul in 1921 (the worse move I ever made in my life) I m perfectly happy. Lewis prosperity makes me boil with envy. I am only asking $25,000 or $20,000 for my novel. Its almost done. The man who sent the remembrance was the manager of your hotel at La Plage d Hyeres. I spoke to Paul R Reynolds about your work (he s my agent and the best in New York--The Post people came to see him every week. Liverite isn t any good) and he said he d like to try your stuff. Explain to him in your letter if you write him (70 5th Ave.) that your wrote Through the Wheat and are the man I spoke of. And if you send him anything that Liverite s had be sure to tell him everywhere it s been. Send me The Dark Cloud please with it appears. We expect to be in Europe three or four years maybe longer. Yours ever, F. Scott Fitz "

To Tom Boyd, 1924

This handwritten letter is one page written in ink from Guaranty Trust Co., Paris when Scott and Tom Boyd were friends and colleagues on the St. Paul Daily News. In addition to being a book reviewer, Boyd also had a bookshop, Kilmarnock Books. Dimensions; 8.5" x 11". Signed boldly by "As Ever Scott." Detailed letter of provenance upon request.

Dear Tom: Guaranty Trust Co., Paris I like the book enormously. First I ll say that. Not quite as well as the first because the style bothered me. Its not as simple as the first--"shore line like a woman s nick!" for example.On the other hand its far bigger feat of imagination--something quite new and more in line with a big development. You might have been a one book man and written the other, but in this you show you have the novelists temperament of sticking within your own conceived scene-- instead of my talent which is merely to interest people the the accidental form of writing novels. I want to write you more but I m in the middle of my own last revision and I m about crazy with nervousness. I ll write again next week. Anyways the book interested me from beginning to end--its flights, the beautifully done idea of the slaves caught in Detroit all of it. Many congratulations. As Ever, Scott

TO EDMUND WILSON [Postmarked October 7, 1924] Villa Marie, Valescure, St. Raphael, France

Dear Bunny:

The above will tell you where we are as you proclaim yourself unable to find it on the map . We enjoyed your letter enormously, collossally, stupendously. It was epochal, acrocryptical, categorical. I have begun life anew since getting it and Zelda has gone into a nunnery on the Pelleponesus…

The news about the play is grand&the ballet too. I gather from your letter that O’Niell&Mary had a great success. But you are wrong about Ring’s book . My title was the best possible. You are always wrong—but always with the most correct possible reasons. (This statement is merely acrocrytical, hypothetical, diabolical, metaphorical). …

I had a short curious note from the latter yesterday, calling me to account for my Mercury story. At first I couldn’t understand this communication after seven blessedly silent years—behold: he was a Catholic. I had broken his heart….

I will give you now the Fitz touch without which this letter would fail to conform to your conception of my character.

Sinclair Lewis sold his new novel to the Designer for $50,000 (950,000.00 francs)—I never did like that fellow. (I do really).

My book is wonderful, so is the air&the sea. I have got my health back—I no longer cough and itch and roll from one side of the bed to the other all night and have a hollow ache in my stomach after two cups of black coffee. I really worked hard as hell last winter—but it was all trash and it nearly broke my heart as well as my iron constitution.

Write to me of all data, gossip, event, accident, scandal, sensation, deterioration, new reputation—and of yourself.

Our love Scott

To Baldwin [1924]

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [Winter of 1924-25]

I am quite drunk

I am told that this is Capri;

though as I remember Capri was quieter

Dear John:

As the literary wits might say, your letter received and contents quoted. Let us have more of the same—I think it showed a great deal of power and the last scene—the dinner at the young Bishops—was handled with admirable restraint. I am glad that at last Americans are producing letters of their own. The climax was wonderful and the exquisite irony of the “sincerely yours” has only been equalled in the work of those two masters Flaubert and Ferber…

I will now have two copies of Westcott’s Apple as in despair I ordered one—a regular orchard. I shall give one to Brooks whom I like. Do you know Brooks? He’s just a fellow here….

Excuse the delay. I have been working on the envelope… That was a caller. His name was Musselini, I think, and he says he is in politics here. And besides I have lost my pen so I will have to continue in pencil … It turned up— I was writing with it all the time and hadn’t noticed. That is because I am full of my new work, a historical play based on the life of Woodrow Wilson.

Act I At Princeton

Woodrow seen teaching philosophy. Enter Pyne. Quarrel scene—Wilson refuses to recognize clubs. Enter woman with Bastard from Trenton. Pyne reenters with glee club and trustees. Noise outside “We have won—Princeton 12-Lafayette 3.” Cheers. Football team enter and group around Wilson. Old Nassau. Curtain.

Act. II. Gubernatorial Mansion at Patterson

Wilson seen signing papers. Tasker Bliss and Marc Connelly come in with proposition to let bosses get control. “I have important papers to sign—and none of them legalize corruption.” Triangle Club begins to sing outside window… Enter women with Bastard from Trenton. President continues to sign papers. Enter Mrs. Galt, John Grier Hibben, Al Jolsen and Grantland Rice. Song “The call to Larger Duty.” Tableau. Coughdrop.

Act III. (Optional)

The Battle front 1918

Act IV.

The peace congress. Clemenceau, Wilson and Jolsen at table…. The junior prom committee comes in through the skylight. Clemenceau: “We want the Sarre.” Wilson: “No, sarre, I won’t hear of it.” Laughter… Enter Marylyn Miller, Gilbert Seldes and Irish Meusel. Tasker Bliss falls into cuspidor.

Oh Christ! I’m sobering up! Write me the opinion you may be pleased to form of my chef d’oevre and others opinion. Please! I think its great but because it deals with much debauched materials, quick-deciders like Rasco may mistake it for Chambers. To me its fascinating. I never get tired of it….

Zelda’s been sick in bed for five weeks, poor child, and is only now looking up. No news except I now get 2000 a story and they grow worse and worse and my ambition is to get where I need write no more but only novels. Is Lewis’ book any good. I imagine that mine is infinitely better— what else is well-reviewed this spring? Maybe my book is rotten but I don’t think so.

What are you writing? Please tell me something about your novel. And if I like the idea maybe I’ll make it into a short story for the Post to appear just before your novel and steal the thunder. Who’s going to do it? Bebe Daniels? She’s a wow!

How was Townsend’s first picture. Good reviews? What’s Alec doing? And Ludlow? And Bunny? Did you read Ernest Boyd’s account of what I might ironicly call our “private” life in his “Portraits?” Did you like it? I rather did.

Scott

I am quite drunk again and enclose a postage stamp.

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [Winter of 1924-25] American Express Co. Rome, Italy.

Dear John:

Your letter was perfect. It told us everything we wanted to know and the same day I read your article (very nice too) in Van. Fair about cherching the past. But you disappointed me with the quality of some of it (the news)—for instance that Bunny’s play failed and that you and Margaret find life dull and depressing there. We want to come back but we want to come back with money saved and so far we haven’t saved any—tho I’m one novel ahead and book of pretty good (seven) short stories. I’ve done about 10 pieces of horrible junk in the last year tho that I can never republish or bear to look at—cheap and without the spontaneity of my first work. But the novel I’m sure of. It’s marvellous.

We’re just back from Capri where I sat up (tell Bunny) half the night talking to my old idol Compton Mackenzie. Perhaps you met him. I found him cordial, attractive and pleasantly mundane. You get no sense from him that he feels his work has gone to pieces. He’s not pompous about his present output. I think he’s just tired. The war wrecked him as it did Wells and many of that generation.

To show how well you guessed the gossip I wanted we were wondering where the * * * *s got the money for Havana, whether the Film Guild finally collapsed (Christ! You should have seen their last two pictures.) But I don’t doubt that * * * * and * * * * will talk themselves into the cabinet eventually. I’d do it myself if I could but I’m too much of an egoist and not enough of a diplomat ever to succeed in the movies. You must begin by placing the tongue flat against the posteriors of such worthys as * * * * and * * * * and commence a slow caressing movement. Say what they may of Cruze—Famous Players is the product of two great ideas Demille and Gloria Swanson and it stands or falls not by their “conference methods” but on those two and the stock pictures that imitate them. The Cruze winnings are usually lost on such expensive experiments as * * * *.

Is Dos Passos novel any good? And what’s become of Cummings work. I haven’t read Some Do Not but Zelda was crazy about it. I glanced through it and kept wondering why it was written backward. At first I thought they’d sewn the cover on upside down. Well—these people will collaborate with Conrad.

Do you still think Dos Passos is a genius? My faith in him is somehow weakened. There’s so little time for faith these days.

The Wescott book will be eagerly devoured. A personable young man of that name from Atlantic introduced himself to me after the failure of the Vegetable. I wonder if he’s the same. At any rate your Wescott, so Harrison Rhodes tells me, is coming here to Rome.

I’ve given up Nathan’s books. I liked the 4th series of Prejudices. Is Lewis new book any good. Hergesheimers was awful. He’s all done…

The cheerfulest things in my life are first Zelda and second the hope that my book has something extraordinary about it. I want to be extravagantly admired again. Zelda and I sometimes indulge in terrible four day rows that always start with a drinking party but we’re still enormously in love and about the only truly happily married people I know.

Our Very Best to Margaret

Please write!

Scott

(OVER)

In the Villa d’Este at Tivoli [Como] all that ran in my brain was:

“An alley of dark cypresses

Hides an enrondured pool of light

And there the young musicians come

With instruments for her delight

……….locks are bowed

Over dim lutes that sigh aloud

Or else with heads thrown back they tease

Reverberate echoes from the drum

The still folds etc”

It was wonderful that when you wrote that you’d never seen Italy—or, by God, now that I think of it, never lived in the 15th century.

But then I wrote T. S. of P. without having been to Oxford.

TO JOHN O'Hara

[1924, December] Hotel des Princes Rome, Italy

Dear Mr. O’Hara

The Sapho followed me around Europe + reached me here. We had some people to dinner the night it came + we took turns reading it and almost finished the book. Its gorgeous—I’d always wanted to read Sapho but I never realized it would be such a pleasure as you’ve made it.

Thank you, + for your courtesy in sending me a copy thanks again

Sincerely F. Scott Fitzgerald

1925

TO EDMUND WILSON [1925] 14 Rue de Tillsit Paris, France

Dear Bunny:

Thanks for your letter about the book. I was awfully happy that you liked it and that you approved of the design. The worst fault in it, I think is a BIG FAULT: I gave no account (and had no feeling about or knowledge of) the emotional relations between Gatsby and Daisy from the time of their reunion to the catastrophe. However the lack is so astutely concealed by the retrospect of Gatsby’s past and by blankets of excellent prose that no one has noticed it— though everyone has felt the lack and called it by another name. Mencken said (in a most enthusiastic letter received today) that the only fault was that the central story was trivial and a sort of anecdote (that is because he has forgotten his admiration for Conrad and adjusted himself to the sprawling novel) and I felt that what he really missed was the lack of any emotional backbone at the very height of it.

Without making any invidious comparisons between Class A and Class C, if my novel is an anecdote so is The Brothers Karamazoff. From one angle the latter could be reduced into a detective story. However the letters from you and Mencken have compensated me for the fact that of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about and for the even more depressing fact that it was in comparison with the others a financial failure (after I’d turned down fifteen thousand for the serial rights!) I wonder what Rosenfeld thought of it.

I looked up Hemminway. He is taking me to see Gertrude Stein tomorrow. This city is full of Americans—most of them former friends—whom we spend most of our time dodging, not because we don’t want to see them but because Zelda’s only just well and I’ve got to work; and they seem to be incapable of any sort of conversation not composed of semi-malicious gossip about New York courtesy celebrities. I’ve gotten to like France. We’ve taken a swell apartment until January. I’m filled with disgust for Americans in general after two weeks sight of the ones in Paris—these preposterous, pushing women and girls who assume that you have any personal interest in them, who have all (so they say) read James Joyce and who simply adore Mencken. I suppose we’re no worse than anyone, only contact with other races brings out all our worse qualities. If I had anything to do with creating the manners of the contemporary American girl I certainly made a botch of the job.

I’d love to see you. God. I could give you some laughs. There’s no news except that Zelda and I think we’re pretty good, as usual, only more so.

Scott

Thanks again for your cheering letter.

FROM GERTRUDE STEIN Hotel Pernollet Belley (Ain) Belley, le 22 May, 192- [1925]

My dear Fitzgerald:

Here we are and have read your book and it is a good book. I like the melody of your dedication and it shows that you have a background of beauty and tenderness and that is a comfort. The next good thing is that you write naturally in sentences and that too is a comfort. You write naturally in sentences and one can read all of them and that among other things is a comfort. You are creating the contemporary world much as Thackeray did his in Pendennis and Vanity Fair and this isn’t a bad compliment. You make a modern world and a modern orgy strangely enough it was never done until you did it in This Side of Paradise. My belief in This Side of Paradise was alright. This is as good a book and different and older and that is what one does, one does not get better but different and older and that is always a pleasure.. Best of good luck to you always, and thanks so much for the very genuine pleasure you have given me. We are looking forward to seeing you and Mrs. Fitzgerald when we get back in the Fall. Do please remember me to her and to you always

Gtde Stein

FROM EDITH WHARTON Pavilion Colombe St. Brice-Sous-Foret (S&O) Gare: Sarcelles June 8, 1925

Dear Mr. Fitzgerald,

I have been wandering for the last weeks and found your novel—with its friendly dedication—awaiting me here on my arrival, a few days ago.

I am touched at your sending me a copy, for I feel that to your generation, which has taken such a flying leap into the future, I must represent the literary equivalent of tufted furniture & gas chandeliers. So you will understand that it is in a spirit of sincere deprecation that I shall venture, in a few days, to offer you in return the last product of my manufactory.

Meanwhile, let me say at once how much I like Gatsby, or rather His Book, & how great a leap I think you have taken this time—in advance upon your previous work. My present quarrel with you is only this: that to make Gatsby really Great, you ought to have given us his early career (not from the cradle—but from his visit to the yacht, if not before) instead of a short resume of it. That would have situated him, & made his final tragedy a tragedy instead of a “fait divers” for the morning papers.

But you’ll tell me that’s the old way, & consequently not your way; & meanwhile, it’s enough to make this reader happy to have met your perfect Jew, & the limp Wilson, & assisted at that seedy orgy in the Buchanan flat, with the dazed puppy looking on. Every bit of that is masterly—but the lunch with Hildeshiem , and his every appearance afterward, make me augur still greater things!—Thank you again.

Yrs. Sincerely,

Edith Wharton

I have left hardly space to ask if you&Mrs. Fitzgerald won’t come to lunch or tea some day this week. Do call me up.

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [Postmarked, August 9, 1925] Rue de Tilsitt Paris, France

Dear John:

Thank you for your most pleasant, full, discerning and helpful letter about The Great Gatsby. It is about the only criticism that the book has had which has been intelligable, save a letter from Mrs. Wharton. I shall only ponder, or rather I have pondered, what you say about accuracy—I’m afraid I haven’t quite reached the ruthless artistry which would let me cut out an exquisite bit that had no place in the context. I can cut out the almost exquisite, the adequate, even the brilliant—but a true accuracy is, as you say, still in the offing. Also you are right about Gatsby being blurred and patchy. I never at any one time saw him clear myself— for he started out as one man I knew and then changed into myself—the amalgam was never complete in my mind.

Your novel sounds fascinating and I’m crazy to see it. I’m beginning a new novel next month on the Riviera. I understand that MacLeish is there, among other people (at Antibes where we are going). Paris has been a mad-house this spring and, as you can imagine, we were in the thick of it. I don’t know when we’re coming back—maybe never. We’ll be here till Jan. (except for a month in Antibes), and then we go Nice for the Spring, with Oxford for next summer. Love to Margaret and many thanks for the kind letter.

Scott

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [1925]

Dear Sir:

The enclosed explains itself. Meanwhile I went to Antibes and liked Archie MacLeish enormously. Also his poem, though it seems strange to like anything so outrageously derivative. T. S. of P. was an original in comparison.

I’m crazy to see your novel. I’m starting a new one myself. There was no one at Antibes this summer except me, Zelda, the Valentinos, the Murphy’s, Mistinguet, Rex Ingram, Dos Passos, Alice Terry, the MacLeishes, Charles Bracket, Maude Kahn, Esther Murphy, Marguerite Namara, E. Phillips Openheim, Mannes the violinist, Floyd Dell, Max and Chrystal Eastman, ex-Premier Orlando, Etienne de Beaumont—just a real place to rough it and escape from all the world. But we had a great time. I don’t know when we’re coming home—

The Hemminways are coming to dinner so I close with best wishes

Scott

FROM T. S. ELIOT

FABER AND GWYER LTD. Publishers 24 Russell Square, London, W.C.1. 31st December, 1925

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Esqre., % Charles Scribners & Sons, New York City.

Dear Mr. Scott Fitzgerald,

The Great Gatsby with your charming and overpowering inscription arrived the very morning that I was leaving in some haste for a sea voyage advised by my doctor. I therefore left it behind and only read it on my return a few days ago. I have, however, now read it three times. I am not in the least influenced by your remark about myself when I say that it has interested and excited me more than any new novel I have seen, either English or American, for a number of years.

When I have time I should like to write to you more fully and tell you exactly why it seems to me such a remarkable book. In fact it seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James….

By the way, if you ever have any short stories which you think would be suitable for the Criterion I wish you would let me see them.

With many thanks, I am,

Yours very truly, T. S. Eliot

P.S. By a coincidence Gilbert Seldes in his New York Chronicle in the Criterion for January 14th has chosen your book for particular mention.

1926

To James Rennie, 17 July 1926

(Autograph Letter Signed, 1 p., 10"x8")

probably to James Rennie, the actor who played the lead in the Broadway production of The Great Gatsby, regarding Fitzgerald's attempts to convert the book Brigham Young by M.R. Werner into a play.

Villa St. Louis, Juan-les-Pins, Alpes Maritime, France, 17 July 1926.

…I sobered up in Paris and spent three days trying to get Brigham into shape. Then down here I worked on it some more and made a tentative working outline. But I don't believe that I could make the grade and the more I struggle with it the more I'm convinced that I'd simply ruin your idea by making a sort of half-ass compromise between my amateur idea of 'good theat re' and Werner's book. I think your instinct has led you to a great idea but that my unsolicited offer was based more on enthusiasm than on common sense. So I bequeath you the notion of the girl which I think in other hands could be made quite solid, and rather ungracefully retire hoping that Connolly or Craig will make you the sort of vehicle of it that's in your imagination.

You're a man after my own heart and I feel that we have by no means seen the last of each other, even in a theatrical way. My love to Dorothy - it was so nice of you both to come and see Zelda…

Zelda was recovering from an appendectomy at this time. According to Fitzgerald biographer, Andrew Turnbull, the author went out on the town every night with James Rennie during the two weeks Zelda was in the hospital.

1927

To Charles Green Shaw , June 21st, 1927, Ellerslie, Edgemoor, Delaware

Dear Charlie: My reason for the long delay is the unusual one. That, owing to a review I’d read, I didn’t approach “Heart in a Hurricane” with high expectations. I’m happy to say that I was absolutely wrong. It is a damn good piece of humorous writing from end to end —much better than anything of its sort I’ve read in years. The character is quite clear—clearest, if I may say so, when his tastes are least exhaustively cataloged. And the three girls are all recognizable and thoroughly amusing. Best of all is the background. I liked the scene in the Colony, in the tough dive and at the houseparty—and forgave such episodes as the false [thug?] and such epigrams as—but looking over the pages I don’t find any that are so bad! I wish you’d try something with a plot, or an interrelation between two or more characters, running through the whole book. Episodes held together an “idea,” in its fragilest sense, don’t give the opportunity for workmanship or for really effective effects. I take the liberty of saying this because there is so much talent and humor and discernment in the book as a whole.

Remember, if George comes down here we’d love to have you too. This sounds rude—but you know what I mean. Sorry I was so drunk & dull the other night.

With Many Congratulations and Cordial Good Wishes,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Years Later: Dear Charlie: We are at last at peace in the wilderness with nothing to drink but rasberry shrubb, medeaeval mead and applejack. Pray gravity to move your bowels. Its little we get done for us in this world. F.S.F.

To Ina Claire, unknown date, 1927 (first)

Scholars have long known that Fitzgerald was fascinated with actress Ina Claire from the moment as a teenager he first saw her on the stage. What has not been revealed before now is that Claire attended one of the Fitzgerald's notorious parties at the Ellerslie estate in Delaware, where the Fitzgeralds resided from 1927 to 1929. Ina Claire (1893-1985), born Ina Fagan, October 15, 1893, Washington, DC; died February 21, 1985, San Francisco, California; effervescent, blond star of sophisticated Broadway comedy in the late 1920s; American actress film and Broadway; films include: "The Awful Truth" 1929; "The Royal Family of Broadway" 1930; "Rebound" 1931; "Ninotchka" 1939; "Claudia" 1943. Married to actor John Gilbert 1920-1931. From the lobby of the Biltmore Hotel in Wilmington, Fitzgerald sends this letter to the actress.

Autograph Letter Signed ("F. Scott Fitzgerald") in black fountain pen ink on Wilmington, DE, n.d., on Du Pont Biltmore letterhead. 6" x 9 1/2", 1 page (recto only).

Fabulously beautiful Creature / Faultlessly groomed I shall be on hand a little after five and in one of my fleet of swift Rolls-Royces whisk you in a 3 1/2 minutes to our palace of delights upon the limpid Delaware. A thousand Cercassian girls and eunuchs will perform a march while we dine (at 6) upon bats wings and Chateau Yquem 1909.

To Ina Claire, unknown date, 1927 (second)

Autograph Letter Signed ("Gene Marky") in black fountain pen ink on Edgemore, DE, n.d. (but the morning after the previous letter was written), on "Ellerslie" letterhead,8 1/2" x 11", 1 page (recto only).

Letter to Ina Claire, apologizing for his previous night's behavior. All the promise of the previous lot's letter evaporates in the first line of this note, written the next morning in the fog of a hangover.

Whether I passed out or was even more offensive I don't know - the only thing in my favor was that I had a dim foreboding of catastrophe from about the time the Hergesheimers left, & I wanted to get you home as soon as possible. What ho~! But nevertheless less I like you too much to endure the lousy impression you will inevitably carry away & this is wa-wa-wa-wa-wa-wa-wa-wa (& all that sentence & old fashioned time honored unacceptable, unwelcome inevitable apology, that you can doubtless fill out for yourself).

... Can you more or less have breakfast with me? I await below.

None of the published biographies record what went wrong at the dinner. It's possible that Zelda Fitzgerald, if she was present, could have engineered some sort of scene; or Fitzgerald my simply be embarrassed by his own clumsy pass at Claire that may or may not have succeeded.

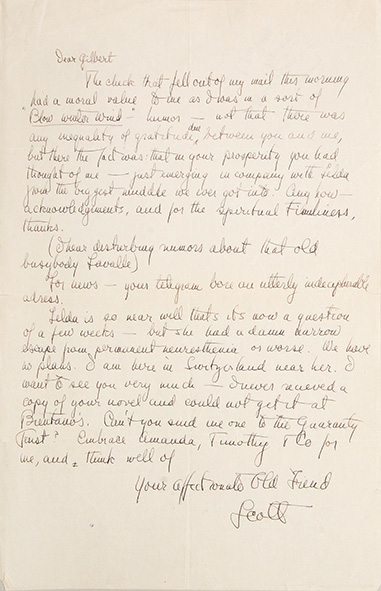

To Gilbert Seldes, unknown date, 1927

Two page ALS. Fitzgerald writes to Gilbert Seldes from “Ellerslie,” Edgemoor, Delaware. Undated, but probably 1927. Fitzgerald is clearly in a jolly holiday mood. There is a marginal postscript in Fitzgerald’s hand regarding a letter sent by Zelda to Seldes.

The doll was beautiful – I sleep with it. You are the dearest grandmother a little girl ever had… As I sit here in my spacious twenty room mansion, hearing the howling of the winds outside and the groans of my toiling servants below, I think of how wonderful it is to be born a German princelet… I don’t blame either of you for being disgusted with our public brawl the other day… we are sober and almost the nicest people I ever met… our difference of opinion which had had been going on for a miserable fortnight for two weeks before we came to New York and led to all the unpleasantness, is settled and forgotten.

Scott.

1928

TO EDMUND WILSON [Probably spring, 1928] “Ellerslie” Edgemoor, Delaware

Dear Bunny: …

All is prepared for February 25th. The stomach pumps are polished and set out in rows, stale old enthusiasms are being burnished with that zeal peculiar only to the Brittish Tommy. My God, how we felt when the long slaughter of Paschendale had begun. Why were the generals all so old? Why were the Fabian society discriminated against when positions on the general staff went to Dukes and sons of profiteers. Agitators were actually hooted at in Hyde Park and Anglican divines actually didn’t become humanitarian internationalists over night. What is Briton coming to— where is Milton, Cromwell, Oates, Monk? Where are Shaftsbury, Athelstane, Thomas a Becket, Margot Asquith, Iris March. Where are Blackstone, Touchstone, Clapham-Hopewellton, Stoke-Poges? Somewhere back at G.H.Q. handsome men with grey whiskers murmured “We will charge them with the cavalry” and meanwhile boys from Bovril and the black country sat shivering in the lagoons at Ypres writing memoirs for liberal novels about the war. What about the tanks? Why did not Douglas Haig or Sir John French (the big smarties) (Look what they did to General Mercer) invent tanks the day the war broke out, like Sir Phillip Gibbs the weeping baronet, did or would, had he thought of it.

This is just a sample of what you will get on the 25th of Feb. There will be small but select company, coals, blankets, “something for the inner man.”

Please don’t say you can’t come the 25th but would like to come the 29th. We never receive people the 29th. It is the anniversary of the 2nd Council of Nicea when our Blessed Lord, our Blessed Lord, our Blessed Lord, our Blessed Lord—

It always gets stuck in that place. Put on “Old Man River” or something of Louis Bromfields.

Pray gravity to move your bowels. Its little we get done for us in this world. Answer.

Scott

Enjoyed your Wilson article enormously. Not so Thompson affair.

To Mr. Robert Newman, 153 South St. Pittsfield, Mass, Etats Unis.

Paris: Mai 16th, [ca. 1928.] Postcard

Dear Mr. Newman:

Thanks for your kind letter. Thinking you might like to know what I looked like I am sending you some pictures (on the other side) that I had taken.

Sincerely + Gratefully F Scott Fitzgerald

[And in lower left corner separated by a diagonal line:] The resemblance is said to be excellent.

On the verso of the card is an image depicting side-by-side photos of "Estomac dun alcoolique," on the left, and "Estomac sain" on the right (this card is from the "Ligue Nationale Contre LAlcoolisme 147, Boulevard Saint-Germain, Paris (VI)). Underneath the photo of the healthy stomach, Fitzgerald has put an arrow and notation, "at 22," and underneath the alcoholic stomach, Fitzgerald has put an arrow and notation, "at 32."

1929

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [Probably January or February, 1929] % Guaranty Trust

Dear John:

My depression over the badness of the novel as novel had just about sunk me, when I began the novellette—John, it’s like two different men writing. The novellette is one of the best war things I’ve ever read—right up with the very best of Crane and Bierce—intelligent, beautifully organized and written—oh, it moved me and delighted me—the Charles-town country, the night in town, the old lady—but most of all, in the position I was in at 4 this afternoon when I was in agony about the novel, the really fine dramatic handling of the old lady—and—silver episode and the butchering scene. The preparation for the latter was adroit and delicate and just enough.

Now, to be practical—Scribner’s Magazine will, I’m sure, publish the novellette, if you wish, and pay you from 250-400 therefore. This price is a guess but probably accurate. I’d be glad to act as your amateur agent in the case. It is almost impossible without a big popular name to sell a two-part story to any higher priced magazine than that, as I know from my experience with Diamond Big as the Ritz, Rich Boy, ect. Advise me as to whether I may go ahead—of course authority confined only to American serial rights.

The novel is just something you’ve learned from and profited by. It has occasional spurts—like the conversations frequently of Brakespeare, but it is terribly tepid—I refrain —rather I don’t refrain but here set down certain facts which you are undoubtedly quite as aware of as I am.

…

I’m taking you for a beating, but do you remember your letters to me about Gatsby. I suffered, but I got something like I did out of your friendly tutelage in English poetry.

A big person can make a much bigger mess than a little person and your impressive stature converted a lot of pottery into pebbles during the three years or so you were in the works. Luckily the pottery was never very dear to you. Novels are not written, or at least begun with the idea of making an ultimate philosophical system—you tried to atone for your lack of confidence by a lack of humility before the form.

The main thing is: no one in our language possibly excepting Wilder has your talent for “the world,” your culture and acuteness of social criticism as upheld by the story. There the approach (2nd and 3rd person ect) is considered, full scope in choice of subject for your special talents (descriptive power, sense of “le pays,” ramifications of your special virtues such as loyalty, concealement of the sensuality that is your bete noire to such an extent that you can no longer see it black, like me in my drunkeness.

Anyhow the story is marvellous. Don’t be mad at this letter. I have the horrors tonight and perhaps am taking it out on you. Write me when I could see you here in Paris in the afternoon between 2.30 and 6.30 and talk—and name a day and a cafe at your convenience—I have no dates save on Sunday, so any day will suit me. Meanwhile I will make one more stab at your novel to see if I can think of anyway by a miracle of cutting it could be made presentable. But I fear there’s neither honor nor money in it for you

Your old and Always

Affectionate Friend

Scott

Excuse Christ-like tone of letter. Began tippling at page 2 and am now positively holy (like Dostoevsky’s non-stinking monk)

To Gilbert Seldes, unknown date, 1929

One page ALS. Fitzgerald writes to Gilbert Seldes from France. Undated, but likely in 1929. I was delighted, so was Zelda, to hear that you’re back in Europe. Ring [Lardner] sent me a clipping about your play – I know how it feels to see one go pop before your eyes and I deeply sympathized with you… Zelda has been sick on and off for a year and we’ve come to this little lost town for a widely famed salt cure for her…

[he writes of their plans for the coming months, inviting Seldes to visit]…

After that, our plans depend, as usual, on finance…

Always Your Friend,

Scott Fit-.

1931

TO JOHN PEALE BISHOP [Received May 5, 1931] Grand Hotel de la Paix Lausanne

Dear John: