F. Scott Fitzgerald's Life In Letters

The Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald

Preface and Editorial Notes On This Collection

This Collection of Letters written and received by American author F. Scott Fitzgerald has been compiled by Anton Rudnev in April 2024 and includes practically all published Scott Fitzgerald's letters. Collection designed specifically for the Fitzgerald: "Texts and Translations" on-line projects.

The scope of this Collection does not include Fitzgerald's letters to and by: Zelda Fitzgerald (his wife), "Scottie" Fitzgerald (his daughter), Harold Ober and his wife Ann (his agent for magazine writings), Maxwell E. Perkins (his editor at Scribner's), and letters to and from Fitzgerald's friends: Ernest Hemingway, John Peale Bishop and Edmund Wilson. This correspondence was collected as separate files. Also, all Ginevra King's letters to Fitzgerald (and Scott's letter to her) are in separate file.

Also, this Collection does not included any public (or, open) letters, published in periodics as sepatate items.

The texts for this Collection were taken from:

Life In Letters: F. Scott Fitzgerald, ed. by (base text, from which were excluded the letters to aforementioned persons);

Additional letters were added from: a) Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald, ed. by, and The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, ed. by Turnbull.

Some letters were added from different auctions' catalogues available on-line.

All reasonable efforts were taken to provide the accurateness of transcriptions, and these texts were checked against printed textes or available scans of the documents.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: 1907–1919

Chapter 2: 1919–1924

Chapter 3: 1924–1930

Chapter 4: 1930–1937

Chapter 5: 1937–1940

Chapter 1: 1907–1919

xxx. TO: Edward Fitzgerald

ALS, 1 p. Scrapbook. Princeton University

Camp Chatham stationery. Orillia, Ontario

July 15, 07

Dear Father,

I recieved the St Nickolas today and I am ever so much obliged to you for it.

Your loving son.

Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

The earliest dated letter by Fitzgerald.

The St. Nicholas, a popular children’s magazine.

xxx. TO: Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald

Summer 1907

Scrapbook. Princeton University

Camp Chatham. Orillia, Ontario.

Dear Mother,

I wish you would send me five dollars as all my money is used up. Yesterday I went in a running contest and won a knife for second prize. This is a picture of Tom Penney and I starting on a paper chase.

Your loving son

Scott Fitzgerald

xxx. TO: Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald

Scrapbook. Princeton University

July 18, 07

Dear Mother, I recieved your letter this morning and though I would like very much to have you up here I dont think you would like it as you know no one hear except Mrs. Upton and she is busy most of the time I dont think you would like the accomadations as it is only a small town and no good hotels. There are some very nise boarding houses but about the only fare is lamb and beef. Please send me a dollar becaus there are a lot of little odds and ends i need. I will spend it causiusly. All the other boys have pocket money besides their regullar allowence.

Your loving son

Scott Fitzgerald.

xxx. FROM: Edward Fitzgerald

July 30, 1909.

Princeton University

TL, 1 p. Scrapbook.

Master Scott Fitzgerald,

Frontenac, Minn.

My dear Scott:

Yours of July 29th received. Am glad you are having a good time. Mother and Annabelle1 are very well and enjoying Duluth. I enclose $1.00. Spend it liberally, generously, carefully, judiciously, sensibly. Get from it pleasure, wisdom, health and experience.

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald's sister.

xxx. TO: Mrs. Richard Taylor

Postmarked 14 February 1910

St. Paul, Minnesota

Postcard. Princeton University

Dear Cousin Cece

Thank you ever so much for the picture of you house. I think it is aufully pretty. The one on the post card looks something like it. I think.

Your loving cousin

Scott Fitzgerald

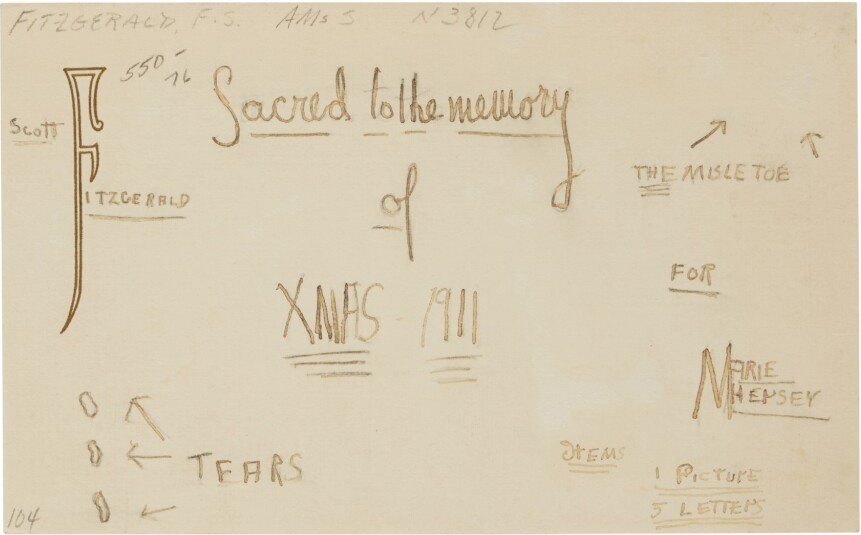

xxx. TO: Marie Hersey

ANS, 1 page, circa 1911

The Misletoe → [some item no longer present]

tears → [three circles]

Sacred to the memory of Xmas 1911

Scott Fitzgerald

Items

1 Picture

5 Letters

Notes:

note from a lovesick young Fitzgerald to his childhood friend and "first love" commemorating his first Christmas home from boarding school.

xxx. TO: Elizabeth Magoffin

Postmarked 12 January 1912

Newman School letterhead, Hackensack, New Jersey

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Dear Miss Magoffin:

We arrived three hours late in New York. (Doggone it my pen spluttered tiny blots all over)

To begin again at a safe distance—Tell the girls that its disgracful they dont answer my letters. I wrote both MARIE! and ELENOR! and I intend to write all of them. Dont say anything but Marie promised me her picture and I havn't gotten it yet. Bob Clark is wild about Elenor Alair. Crazy about her. I hope she's not crazy about him To tell you the truth I am not crazy about anyone. Of course I fill my letters to my favorites with a lot of—well—nonsense but as far as telling them outright that you like them best i've come to the conclusion its foolish. A girl should always be kept guessing—always. I'm afraid I am boring you with my silly philosophy of human nature

So Ta-Ta So-Long GOODBYE

Your Admirer

Francis Scott Fitzgerald

Playright

xxx. TO: Elizabeth Magoffin

Postmarked 17 February 1912

Newman School letterhead, Hackensack, New Jersey

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

My Dear Elizibeth:

Since you did not answer my other letter I suppose I will have to write you again. I addressed the other letter to Summit Avenue near Macubin but probably it is at the dead letter office and clerks with spectacles and red whiskers are vivesecting accounts of “Bear cats” and “Tongo Argentines.” Tell Marie that I dont think she got my last letter as I didn't mail it. Tonight we have a dance followed by a minstrel show. I got two dollars for a poem.1 Hurray for me. So you see if you can write verses about sparks and other combustibles I can dribble of Cavalier Ballads.2

Your friend Scott (Playright)

P.S. For Heavans sake send your adress

Notes:

1 Unidentified.

2 Miss Magoffin had written a poem to Fitzgerald about his “spark.”

xxx. To Elizabeth Craig Clarkson (“Litz”)

St. Paul, Minn

September 15, 1913

Dear Litz:

I write to tell you how very sorry I was that I couldnt accept your “invite” yesterday. But bronchitis interposed its highly annoying hand and spoiled it. Remember, Litz, until we meet “when the Holly blooms” in three months you are “She who (quick somebody, give me [?] an appropriate [crossed-out word] quatushun [sic]) well anyway [crossed out word] you are she who. I am in a particularly despondent and dissipated mood. Outside the sun is shining but I am perfectly positive it is only doing it out of spite. In the church across the way they are singing hymns. I think they might be at least sing (Hers) [?] I am going to write you at Miss Hartridges School, Plainsfield N.J. and I swear it will be a sensible letter not a foolish jumble like this for

My mind is all a-tumble

And the letter seems a jumble

for the words they seem to mumble

And my pens about to stumble

and the papers made to jumble

So I sign myself your humble

Servant

Francis Scott Fitzgerald

P.S. My query of “Have you no compunctions” is still unanswered. Any time you have compunctions or any other discease [sic] send me a night letter—

(signed) Scott—

Notes:

This was written the day after he was accepted at Princeton.

xxx. To Elizabeth Craig Clarkson (“Litz”)

15 University Park, Princeton, N. J.

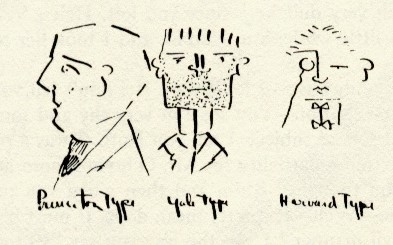

Sept. 26th, 1913

Dear Elizabeth:

Nunc Sum Studens. (Latin.) I am now a Princetonian. Its great. Im crazy about it. Today we had the rushes. The Sophs mass in a body in front of the gym and the Freshmen try to rush their way in. You can imagine it. Four hundred Freshmen, among them yours truly, against 380 Sophs. Everything was ruined shirts, jerseys, shoes, socks, trou, hats ect. were strewn over the battle-field. I was completely done up. I was in the front row and a soph and I almost killed each other. I am a mass of bruises from head to foot. When we got in we elected a class President, Vice Pres. and sec. When we came out again the sophs. tried to bust our line. We beat H——— out of them. Then we paraded around the campus, yelling “whoop it up for seventeen,” which is a wonderful song. Then we cheered and sang. Zip!!! This is some place. I have a big piece of some sophs shirt. Somebody has a big piece of my jersey. (Lord only knows who.) Tonight is the cannon rush so if you never hear from me again youll know I died a freshman.(gentle pathos.) The “horsing” (or hazing) is going on now. Its very foolish. Freshies have to carry their cap in their mouths and by the way our uniforms are some class (not)

(Picture of me in my Freshman uniform)

Black cap --->

Black jersey --->

Cordoroy [sic] Trou --->

Black socks --->

Black shoes --->

The Sophs. make you tell a funny story and then wont laugh but tell you to finish. Then they tell you to dig for the point. (N.B. You dig) This morning I gave.

xxx. TO: Marie Hersey

ALS, 1 p. Scrapbook. Princeton University

Princeton, New Jersey

(Letter sent Jan 29, 1915)

Thurs

My Very Very Dear Marie:

I got your little note

For reasons very queer Marie

You’re mad at me I fear Marie

You made it very clear Marie

You cared not what you wrote

The letter that you sent Marie

Was niether swift nor fair

I hoped that you’d repent Marie

Before the start of Lent Marie

But Lent could not prevent Marie

From being debonaire

So write me what you will Marie

Altho’ I will it not

My love you can not kill Marie

And tho’ you treat me ill Marie

Believe me I am still Marie

Your fond admirer

Scott

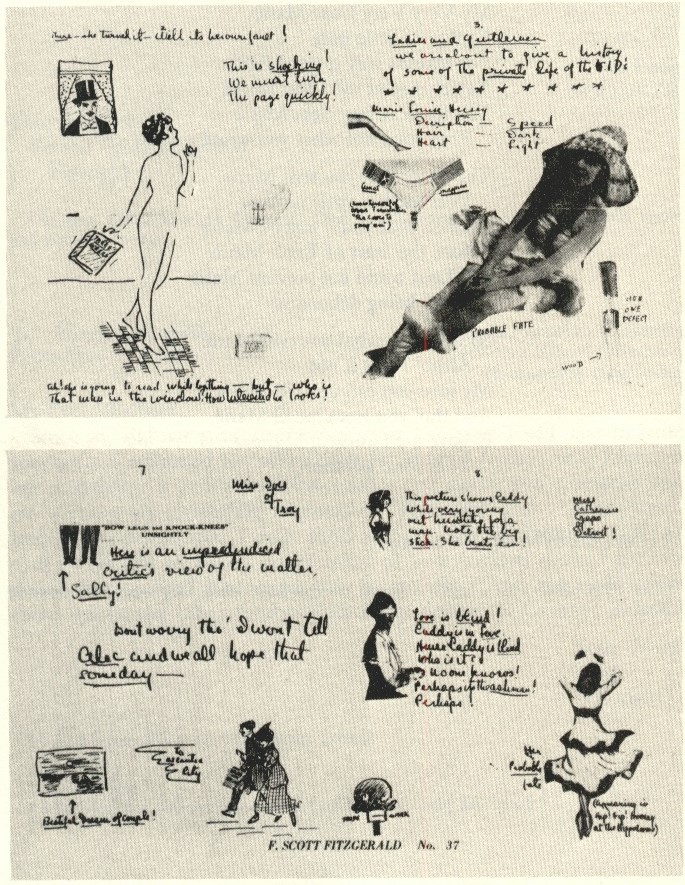

xxx. To: Marie Hersey

ALS with collage, 8 pp.;

taken from catalogues:

1) Auctioned: Modern First Editions... Sotheby Parke Bernet, Inc. Sale № 3476 (20 February 1973), Item # 207 (pp. 2 and 3);

2) Autograph Letters Manuscripts Documents, Catalogue 102, Kenneth W. Rendell, Inc. (1975), Item # 37 (pp. 7 and 8).

Princeton, New Jersey

Early 1915

[1]

Letter for Hersey!

My heavens, who'd write to her - must be a mistake. What are the initials - M. L. - well. that's write (a pun). However I would addvise Miss Hersey if she wants to keep her peace of mind and moreover her modesty not to look at middle pages of this sheet...

[2 - see picture below]

There - she turned it- Well, its heroine is Janet.

This is shocking! We must turn the page quickly!

Ah! She's going to read while bathing - but - who is that man in the window? How interested he looks!

[3 - see picture below]

Ladies and Gentlemen

We are about to give a history of some of the private life of the K.I.D.

***

Marie Loise Hersey

Description - Speed

Hair - Dark

Heart - Light

This is her coat of arms. Translation "She loves to snap 'em."

Probable fate

Her one defect - wood

[4]

next, we have her roommate Marjorie Howey Muirs!

...She will probably say this is all [image of a bull].

[5]

Poor Ginevra! This is some school she's going to next year! It's not a finishing school but it will be her finish! By that time she'll be well-fitted to [printed] Become a Nurse! Poor Ginevra!

[6]

- unavalable page dedicated to unknown girl

[7 - see picture below]

Miss Ives of Troy

[printed] Bow-legs and knock-knees

unsightly

Here is an unpredjudiced critics' view of the matter. Sally!

Don't worry tho' I won't tell Alec and we all hope that someday -

Beautiful Dream of Couple

To Atlantic City

[8 - see picture below]

Miss Catherine Craps of Detroit!

This Picture shows Caddy while very young out hunting for a man. Note the big stick! She beats 'em!

Love is blind! Caddy is in love! Hence Caddy is blind. Who is it? No one knows. Perhaps it's the ashman! Perhaps!

Her probable fate: appearing in Hip! Hip! Hooray! at the Hippodrome.

Trade mark.

xxx. TO: Ruth Howard Sturtevant

Princeton, New Jersey

ALS, 8 pp. University of Virginia

May Something or other [May 1915]

Dear Howard

I have absolutly no excuse for writing you as you were careful to leave very few loopholes in your letter, but I want to write you and with most people thats reason enough. If you had begun that note “My Dear Mr. Fitzg—” I'd have never forgiven you and even “F. Scott Fitz” was a compromise. Its been very dull here since you left. Helen Walcott lightened our misery for a little while; Stu, Harold, and I took her to Cottage Club for tea.

As regards your Adjective—2 let it wait. If I don't tell you what it is it'll always do for conversation—You see I'm very shy and sometimes have to fall back on that sort of subject. I tell you Ruth, I was a pretty enfuriated youth at your extreme partiality for Mr. O'brien-Moore at Campus. You told me what you thought of him and then when you prefered his conversation to mine—Well—Its pretty mean dope. It must be his “handsome face and daredevil manner.” I like the way you say “Its too bad you can't come to our dance.” How do you know we couldn't come—there are from three to five days between every exam.

Here I am writing to you, Ruth, when Ginevra's3 letter lies unanswered on my desk. Pretty darn devoted I call it. Really Ruth I think you're fine. I like you a lot—I think

D—mit! → [ink blot]

especially we could have a wonderful quarrel if we ever got to know each other—because you see, we're both blondes + could find the other's weak points. It'd be a mean affair genererally and “more darn fun.” I suppose you're having a dull time waiting for the Washington parlor snakes to float back from college + prep-school. I wish I was a Washington parlor Snake—I don't suppose it would be “all right” though—I was just thinking that if we both lived in St. Paul we could have a desperate affair—wouldn't it be interesting. (This savours 'un petit peu' of Mr. Obrien-Moore.)

As it is we'll probably never come across each other again. (Sob Stuff)

Ruth—(reading the letter)—“Why the ridiculous thing—Is he trying to slipover some second class stone-age sentiment when he's only met me twice in his life the fresh thing”

No Ruth—Far be it—I'm too suspicious of bloneds—however I think you're one of the cleverest ones I've ever met and I've another hunch we're going to be joyful, Ruth.

Ruth, just for fun answer this—will you Then I'll answer your answer and then we'll stop. How about it?

How is “dear Old Yale.” By the time you get this we'll have beaten them in baseball. Remember in senior year your going to sit on the stage in the cafe scene of the Δ show. Is that your debutante year. Au revoir. I am

Notes:

2 One of Fitzgerald's lines with girls at this time was to say he had thought of an adjective for them—which he would reveal after he knew them better.

3 Ginevra King, a Lake Forest, Ill., debutante who was Fitzgerald's first serious love. He met her at a party in St. Paul in January 1915 and maintained an elaborate correspondence with her while she was at Westover School. None of his letters to her survives.

xxx. TO: Ruth Howard Sturtevant

After 13 November 1915

Princeton, New Jersey

ALS, 8 pp. University of Virginia

Dear Ruth:

I'm feeling in a very blue and despondent mood so this is going to be a very blue and despondent letter

Saw Stu Walcott between halves and made a desperate effort to get over but the 2nd half started before I was out of the Princeton stand. It certainly was a heart-breaker wasn't it.1 I gloomed all evening. While the rest of the college was drownding its sorrows in Busbys, Maximes, Jacks and other churches along Broadway I was sitting the Elton Hotel in Waterbury with Ginevra King, another Westover girl, and another Princetonian. All through dinner a Yale crowd kept singing “Bright College Beers”2 their Univesity anthem and after dinner to heap insult apon injury we danced to “Boola-Boola” Its a wonder I didn't stand up and sing the undertaker's song; I had a corpse looking like the queen of the Folies Bergere. Then we rose at five-forty-five and sailed up to New York in the cold gray dawn.

Ruth Sturtevant I'd like to see you a lot right now. I imagine you'd be an awfully cheering person to talk to. I alway talk too D——seriously with G.K. and end up with a pronounced case of melancholia but I think you'd be likely to leave a person in a good humor—I don't know why!

I suppose it must have been an awful relief to you to get out of the penententiary for a little carouse but now that you're again breaking stones with the other prisoners you're probably correspondingly lower. If you could only see me sitting alone in my room on a dismal unhappy tonight—Sunday night at that—with the rain pouring down outside and nothing to look forward to but weeks of grind and Δ work

Why do you always begin your letters “My Dear Scott.” Are we on such terribly formal terms. I should think that after our friendship of years and the weeks we have constantly spent together you might drop the my—or the my and the Scott.

No Ruth there is not a word not so compromising as either love or maledictions so until you make up your mind what to use you'd better just sign “Ruth Howard”

When I said you were like Aleda3 I didn't mean at all that you looked like her because naturally you don't at all. Your resemblance to Aleda is purly in one thing which I won't put on paper as you'd surly show it to her and I don't think either of you would like it. Tell Aleda for me that she is very beautiful but extraordinarily stonyhearted. (Next time I see you I'll tell you why you're like her. Its a very essential and important point which you have, or lack, in common)

I suppose you trotted around at the St. Anthony dance, got rushed to death and by three oclock were the only girl in the room who had not lost her color and I suppose you met a perfectly wonderful Yale man who promised to “write you every day and send his picture.

Don't you think Ruth that for Sunday night this is a very brilliant letter. I'd illustrate it with those wonderful pen and ink sketches of mine but I havn't the pep but my next letter will be a regular “Life.”4 Best to Aleda and Curses to Margaret also remember me “very formally” to Helen James.—and in your next letter don't mention the football game. I'd been saving this letter so that I could gloat in it but doggone it I might as well have sent it a week ago. Committing Myself I am

With Love Scott

Notes:

1 Yale upset Princeton at New Haven, 13-7, on 13 November 1915.

2 “Bright College Years,” the Yale alma mater.

3 Alida Bigelow, a St. Paul friend.

4 Life was a humor magazine before Henry Luce bought the title for his picture magazine.

xxx. To: Elizabeth Taylor

Signed Postcard. Princeton.

Nov 1, 1916

Dear Tommy:

Do they still call you Tommy? Are you fat or thin? Remember me to your grandmother.

Your cousin

Scott

xxx. To: Virginia Taylor

Signed Postcard. Princeton.

Princeton, New Jersey.

Nov 1, 1916

Dear Gigi:

Do you remember me or have you forgotten me Altogether your affectionate cousin Scott

Do I look like this or like this

xxx. TO: Elizabeth Craig Clarkson (“Litz”)

mailed on Thursday, December 7, 1916

Princeton, FSF Additional Papers, Box 24, Folder 11; sold at Bloomsbury Auctions, New York City, in the Literature Sale (November 28, 2007, Lot 188).

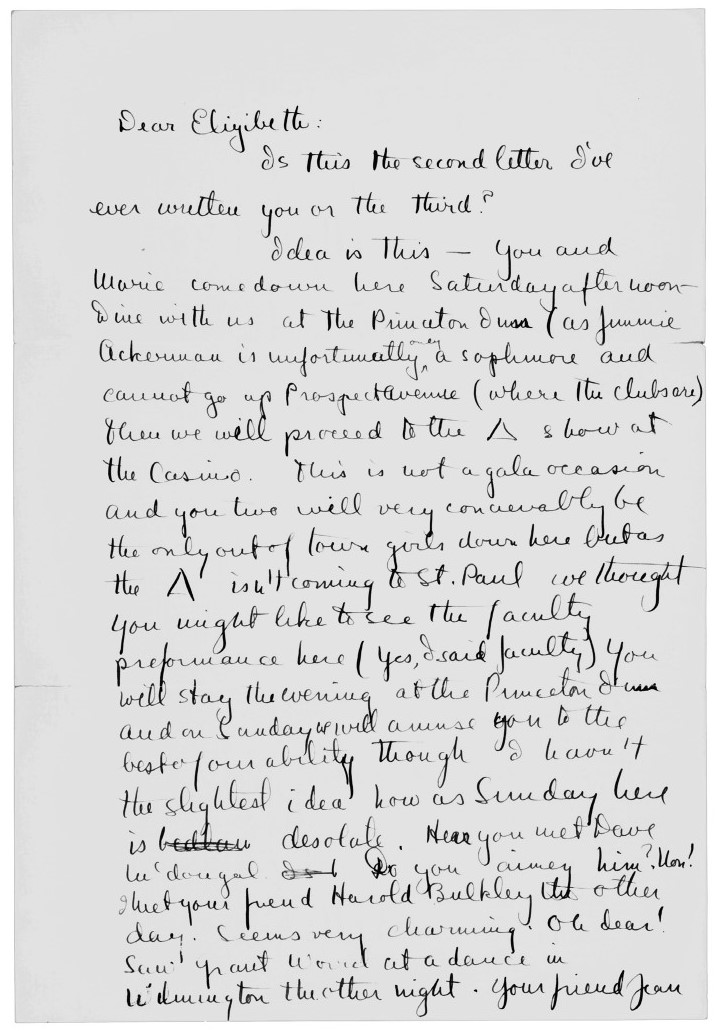

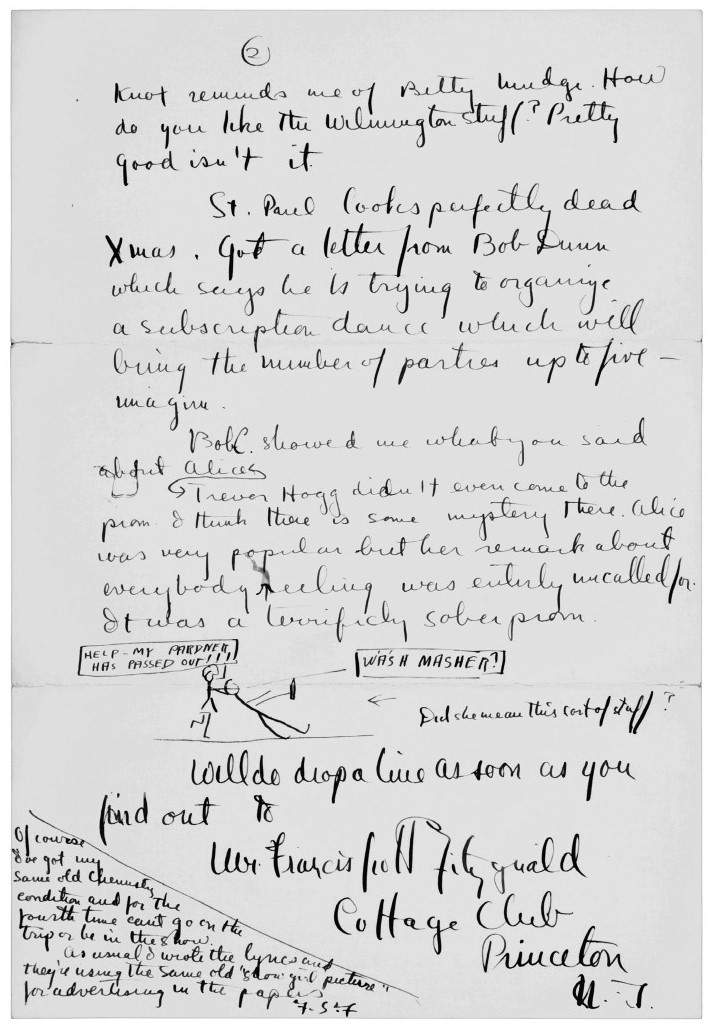

Is this the second letter I’ve ever written you or the third?

Idea is this—You and Marie come down here Saturday afternoon—Dine with us at the Princeton Inn (as Jimmie Ackerman is unfortunately only a sophmore and cannot go up Prospect Avenue (where the clubs are). Then we will proceed to the A show at the Casino. This is not a gala occasion and you two will very concievably be the only out of town girls down here but as the A isn’t coming to St. Paul we thought you might like to see the faculty preformance here (Yes, I said faculty) You will stay the evening at the Princeton Inn and on Sunday we will amuse you to the best of our ability though I havn’t the slightest idea how as Sunday here is bedlam desolate. Hear you met Dave Mcdougal. Do you aimez him? Non! I met your friend Harold Bulk- ley the other day. Seems very charming. Oh dear! Saw Grant Worrel at a dance in Wilmington the other night. Your friend Jean Knox reminds me of Betty Mudge. How do you like the Wilmington stuff? Pretty good isn’t it.

St. Paul looks perfectly dead Xmas. Got a letter from Bob Dunn which says he is trying to organize a subscription dance which will bring the number of parties up to five—imagine.

Bob C. showed me what you said about Alice. Trevor Hogg didn’t even come to the prom. I think there is some mystery there. Alice was very popular but her remark about everybody reeling was entirely uncalled for. It was a terrificly sober prom.

Well do drop a line as soon as you find out to Mr. Francis Scott Fitzgerald Cottage Club Princeton N.J.

Of course I’ve got my same old Chemistry condition and for the fourth time can’t go on the trip or be in the show.

As usual I wrote the lyrics and they’re using the same old “show girl picture” for advertising in the papers F.S.F.

xxx. Inscription TO: Ruth Howard Sturtevant

Inscription on Safety First! (1916); The University of Virginia.

Cottage Club Princeton, New Jersey

[December, 1916]

Ruth Howard Sturtevant Wishing you a very snakey Xmas vacation F. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

Includes extra verse to "It is Art".

FSF noted, that pp. 51-52 were shuffled by the printer.

FSF noted at p. 92 after words "I've been around trinagling": "(Not this year tho' as I still have my old Chemistry condition)."

xxx. TO Alida Bigelow

From Turnbull.

Cottage Club Princeton, New Jersey

[Postmarked January 10, 1917]

Dear Alida:

I never felt so depressed in my life as I do this afternoon and what should I do in the middle and lowest point of it but pick up North of Boston.3—It made me still gloomier; but it's well worth reading and for the most part good poetry. The first poem, the one about mending the wall, is the best thing in it I think.

—Much obliged—you were very good to send it. Even the “platitudinous remark” seemed satirical on a day like this however.

I'll send you a one-act play by me when it comes out in the next Nassau Lit. It's called “The Debutante.”—It's a knockout!

Just had a scrap with my English preceptor—he's a simple bone-head and I'm not learning a thing from him. I told him so!

I never had such a simple Christmas vacation as this one. The only two parties I enjoyed particularly were the German and the Lamda Sigma dance. Perhaps there was a reason—tho incidentally I've cut out all drinking for one year. (Good old New Year's resolution.) I suppose you've regaled Ruth with an account of my exploits at the first-named affair—but what bother I!

Isn't it a shame about Mrs. S! I hear from Elkins Owlliphant, however, that she's now back at school.

I wonder if Sandy is going to marry __! Wouldn't this be a suitable pair to travel around the streets of St. Paul! He must have some strange power over woming!

Haven't heard a word from home since I got back here—Gee! Honestly! Never did I feel so low.

It's four o'clock and I have the electric light on—you can imagine what kind of day it [is].

If you can receive books and you won't be shocked I'll send you a knockout called The Confessions of an Inconstant Man. One part of it is rather mean, tho!! You'll have to send it back as another copy is unprocurable for Love or Money.—Tell me whether you want to read it or not.

I got the funniest letter from a girl in New York whom I'd never heard of saying that she had light brown hair and brown eyes and that she wanted to meet me. She said she's seen that picture (awful chromo) of moi in The Times.

Well Alida I'm sorry this letter is so gloomy but that's the form I'm in so it can't be helped.

Give my best to Virginia Sweat and tell her I'm sorry I've got such [a] weak line. I am

Yours till deth,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

3 By Robert Frost.

xxx. TO: Stephen Leacock

Before 16 March 1917

Leacock Home, Orillia, Ontario

Not examined. See Ralph L. Curry, Stephen Leacock (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1959), pp. 119-20.

My Dear Mr. Leacock:

As imitation is the sincerest flattery I thought you might be interested in something you inspired. The Nassau Literary Magazine here at Princeton of which I'm an editor got out a “Chaopolitan number,” as a burlesque of “America's greatest magazine.”

The two stories I wrote “Jemina, a story of the Blue Ridge mountains, by John Phlox Jr” and “The Usual Thing” by “Robert W. Shamless [sic]3 are of the “Leacock school” of humour—in fact Jemina is rather a steal in places from “Hannah of the Highlands.”

I'm taking the liberty of sending you a copy—needless to say it increased our circulation & standing in undergraduate eyes.

Hope you'll get one smile out of it for every dozen laughs I got from the Snoopopaths.4

Very appreciatively yours, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Notes:

3 Brackets in printed text.

4 Leacock replied on 16 March 1917: “Your stories are fine. As Daniel Webster said, or didn't say, to the citizens of Rochester, 'Go on.' “

xxx. To Mrs. Richard Taylor

From Turnbull.

[Princeton University] [Princeton, New Jersey]

June 10, 1917

Dear Cousin Ceci:

Glad you liked the poem. Here are two others.

ON THE SAME PLAY—TWICE SEEN

Here in the figured dark I watch once more

There with the curtain rolls a year away

A year of years—There was an idle day

Of ours when happy endings didn't bore

Our unfermented souls—and rocks held ore,

Your little face beside me, wide-eyed, gay,

Smiled its own repertoire, while the poor play

Reached me as a faint ripple reaches short—

Yawning and wondering an evening thru

I watch alone and chatterings of course

Spoil the one scene which somehow did have charms

You wept a bit, and I grew sad for you

Right there—where Mr. K. defends divorce

And What's-her-name falls fainting in his arms.

Here's another one, very recent, that's rather better. It's called:

WHEN WE MEET AGAIN

The little things we only know

We'll have forgotten,

Put away

Words that have melted with the snow

And dreams begotten

This today

And dawns and days we used to greet

That all could see and none could share

Will be no bond—and when we meet

We shall not care—We shall not care.

And not a tear will fall for this

A little while hence

No regret

Will rise for a remembered kiss

Nor even silence

When we've met

Can give old ghosts a waste to roam

Or stir the surface of the sea

If grey shapes drift beneath the foam

We shall not see—We shall not see.

When life leaps deathward as a flame

Love at the scorching

Of its breath

Casts his mad heart into the same

Fires that are torching

Life to Death

Though cracks may widen in the tomb

Chords from still heart to moving ear

Tremble and penetrate the gloom

We shall not hear—We shall not hear

Colours of mine have filled your eyes,

Light from the morn

Of our last sea

Has gathered to you till the wise

Think love so born

Eternity.

But wisdom passes—yet the years

Will feed you wisdom; age will go

Back to the old—For all your tears

We shall not know—We shall not know.

I can't resist putting in two more.

ON A CERTAIN MAN

He loved me too much, I could not love him

Opened so wide my eyes I could not see,

For all I left unsaid I might not move him

He did not love himself enough for me.

He kissed my hand and let himself, unruddered,

Drift on the surface of my “youth” and “sin”

His was the blameless life, and still I shuddered

Seeing the dark spot where his lips had been.

“How you must hate me, you of joy and brightness

Who have no sentiment—Ah—I'm a bore—”

I smile and lie and pray the God, politeness;

I'll sicken if his curled hair nears once more.

Trembling before the fire, I gasp and rise,

Yawn some and drawl of sleep, profess to nod,

And weird parallels image on my eyes

A devil screaming in the arms of God.

He'd gone too far, had merged his heart somewhere

In my mean self, and all that I could see

Was a raw soul that labored, grovelled there.

I loathed him for that soul—that love of me.

Here's the last one. Do you remember what I said about my capacity for hero worship? Well—

CLAY FEET

Still on clear mornings I can see them sometimes—

Men, gods and ghosts, queens, girls and graces,

Then that light fades, noon sickens, and there come times

When I can see but pale and ravaged places

That they have left in exodus; and seeing

My whole soul falters, as an invalid

Too often cheered. Did something in their being

That was fine pass when my ideal did?

Men, gods and ghosts, damned so by my own damning,

Whether you knew or no, saw or nay,

Either were weak or failed a bit in shamming—

Yet had I known a freedom that could weigh

So much, hung round the heart, I'd sought protection

Once more in those warm dreams, lest you should fall

From that great height to this great imperfection—

So do I mourn—so do I hate you all.

I'm writing a lot now—especially poetry—also drilling and preparing to go to this second camp—Damn this war!

Had I met Shane Leslie when I last saw you? Well, I've seen a lot more of him—He's an author and a perfect knockout—On the whole I'm having a fairly good time—but it looks as if the youth of me and my generation ends sometime during the present year, rather summarily—If we ever get back, and I don't particularly care, we'll be rather aged—in the worst way. After all, life hasn't much to offer except youth and I suppose for older people the love of youth in others. I agree perfectly with Rupert Brooke's men of Grantchester

“Who when they get to feeling old They up and shoot themselves I'm told.”

Every man I've met who's been to war—that is this war—seems to have lost youth and faith in man unless they're wine-bibbers of patriotism which, of course, I think is the biggest rot in the world.

Updike of Oxford or Harvard says “I die for England” or “I die for America”—not me. I'm too Irish for that—I may get killed for America—but I'm going to die for myself.

I'm going to visit in West Virginia and I may stop by Norfolk for a day. Will you give me lunch on say about the twentieth—or will you be away?

Do read The End of a Chapter and The Celt and the World by Shane Leslie—you'd enjoy them both immensely.

I suppose Tom 1 has come and gone—I hear reports of him all over the country. He certainly seems to carry faith and hope with him. He's the old-fashioned Jesuit—the kind they got continually when the best men in the priesthood were all Jesuits.

Went to a reception last week at the Duke de Richelieu's in New York where I consumed great quantities of champagne and fraternized with most of the prominent Catholics—due to champagne. I used to wonder how terribly stiff and formal receptions were possible but I see now that it is the juice of the grape.

One more thing—the most sincere apologies for the cold you got listening to my inane ramblings (of course I don't really think they were inane) on the porch of the Cairo. Give my best to

Sally

Cecilia

Tommy

Ginny.2

And love to Aunt Elise.

Yours, etc.,

F. Scott Fitz

Notes:

1 Cousin Ceci's brother, Thomas Delihant, was a Jesuit priest.

2 Cousin Ceci was a widow with four daughters.

xxx. FROM: Father Sigourney Fay

August 22nd, 1917.

Deal Beach, New Jersey

TLS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Dear Fitz:—

I cannot tell you how delighted I am to have gotten your letter.

First of all as to money: Your $3600 will cover everything except your uniforms. There is no salary for any of us; they expect us to take it out in glory, and really there will be glory enough if we manage to do what I hope we will.

Now, in the eyes of the world, we are a Red Cross Commission sent out to report on the work of the Red Cross, and especially on the State of the civil population, and that is all I can say. But I will tell you this, the State Department is writing to our ambassador in Russia and Japan, the British Foreign Office is writing to their ambassador in Japan and Russia, and I have other letters to our ambassador in Japan and Russia, and to everybody else in fact who can be of the slightest assistance to us. Moreover I am taking letters from Eminence to the Catholic Bishops.

The conversion of Russia has already begun. Several millions of Russians have already come over to the Catholic Church from the schism in the last month. Whether you look at it from the spiritual or temporal point of view it is an immense opportunity and will be a help to you all the rest of your life.

You will be a Red Cross Lieutenant, and I will let you know as soon as I get your commission what your uniform will be.

Will you come on and join me in New York and get your uniforms there at the regular Red Cross place, where you can get them in 24 hours. You are measured at dawn, fitted at noon and fitted out at sunset. Or will you join me in Chicago and we can go thence to San Francisco and bid affectionate farewell to Peevie,2 and get to Vancouver in time for the 27th. Or shall I come to St. Paul, and will we go by the C.P.R. But what will Peevie do then, poor fellow. It is hard enough on him in any case.

I think the best thing you and I can do is to write a book while we are away. I am going to take a Corona typewriter. I am so glad you know how to work one.

We shall have to work very hard going over on your French. Get a Rosenthal method at once and go right through it.

You will have to take plenty of warm clothes as we shall be in a very cold climate most of the time. You will be in Russia three months, not away only three months. Your money ought to be in this form: It costs $1600 for our traveling over and back, and $2000 in a letter of credit while we are living in Russia, as we shall have to keep at least some state.

Now, do be discreet about what you say to anybody. If anybody asks you say you are going as secretary to a Red Cross Commission. Do not say anything more than that, and if you show this letter to anybody, show it only in the strictest confidence. I would not show it to anybody but your mother, father and aunt.

To my mind the most extraordinary thing about it is that we may play a part in the restoration of Russia to Catholic unity. The schismatic church is crumbling to pieces; it has now no State to lean on.

I am tremendously glad you are going to have this experience. It really will change your whole life. Poor Peevie could not go. I was hoping that he might and I would have taken you both in that case.

Leslie3 cannot go as he is not an American citizen, and the Red Cross is now the Government, so they cannot send anybody who is not an American. Besides he could not leave the Dublin; we cannot all be away.

I think the Dublin Review will be jolly glad to get anything we send them, signed with any initials we care to put to it. But I think we had better save our efforts for a book which we will write together, and to which we will put both our names.

Though we get no salary we all have to work hard, and you will have to help me with an enormous amount of correspondence. As you would elegantly express it, “the whole thing is a knock-out.” I sincerely hope the war will be over long before you take to flying.

Now, last of all, whatever you surmise about the commission, keep your brilliant guesses to yourself. You guess far too well. Above all be careful what you say about religion. It is for that very reason that the attaches are Protestant. There will be no Catholice except yourself, myself and my servant. Whatever is done A.M.D.G.4 will be done by you and me. For this reason I shall arrange for you to share my cabin, and we can take a room together when we get to Russia, as it will save some money at least and give us a chance to talk the things over which must be strictly confidential between us.

About your commission—give it up now, and say that as you have heard nothing you have decided to wait until you are of age and then go in for aviation. But I hope to goodness, as I said before that the war will be over before you take to that.

As soon as you have read this letter and shown it at home, burn it.

With best love,

S. W. Fay

Notes:

2 Stephan Parrott.

3 Sir Shane Leslie.

4 Ad majorum dei gloria.

xxx. FROM: Father Sigourney Fay

October 4, 1917.

Deal, N.J.

TLS, 1 p. Princeton University

Dear Fitz:

My note the other day was very short because I was frightfully rushed, and because I had not had time to read your story.1 I have just finished it now and think it is first rate stuff. I should prefer it being called by your own name instead of that of Michael Fane, as that non de plume would give the impression that your story was an imitation of “Youth's Encounter” which it is not.2 Your hero is curiously unlike Michael Fane, and very unlike you or me.

I was interested in your last letter—the way you tried to divide people up. I do not think there are as few classes as you think. There are many different types. I should take as the first type ourselves; the second class Leslie; third class Father Hemmick; fourth class Mr. Delbos;3 fifth class Duc de Richelieu; sixth Aberdeen.

Then there are about four classes more. They dwindle down from the typical business men to the thug.

I think that is all the types there are, but I do not think you can get people under fewer heads than that. Of course in the type individuals vary, but the individual's variations are very slight. It's extraordinary how slight they are. Take ourselves, you and Pevy and I have many superficial differences. Each is due to age and environment. As for instance I am older than both of you. Pevy was educated almost entirely in Europe, you almost entirely here. My education is English, Pevy's French, yours American, but if you remember a long conversation we had in Washington at the University Club in June, you will also remember how we startled one another by our extraordinary likeness in essential things.

It is exactly the same way with Stephen. All my plans hang fire at present. I may go to Europe any day, but I will let you know in plenty of time, then we can make one last effort to go together. With best love.

Cyril S. W. Fay

Notes:

1 Unidentified.

2 Michael Fane was the hero of Compton Mackenzie's Youth's Encounter (1913), which greatly impressed Fitzgerald and his friends.

3 Hemmick and Delbos were on the Newman School staff.

xxx. TO: Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald

ALS, 4 pp. Princeton University

Cottage Club stationery. Princeton, New Jersey

Nov 14th

1917

Dear Mother:

You were doubtless surprised to get my letter but I certainly was delighted to get my commission.

My pay started the day I signed the Oath of Allegiance and sent it back which was yesterday—Went up to Brooke’s Bros yesterday afternoon and ordered some of my equipment.

I havn’t received any orders yet but I think I will be ordered to Fort Lea van worth within a month—I’ll be there three months and would have six additional months training in France before I was ordered with my regiment to the trenches.

I get $141 dollars a month ($1700 a year) with a 10% increase when I’m in France.

My uniforms are going to cost quite a bit so if you havn’t sent me what you have of my own money please do so.

I’m continuing here going to classes until I get orders. I am a second Lieutenant in the regular infantry and not a reserve officer—I rank with a West Point graduate.

Things are stupid here—I hear from Marie and Catherine Tighe occasionally + got a letter from Non two weeks ago—I hear he’s been ordered to Texas.

Went down to see Ellen Stockton in Trenton the other night. She is a perfect beauty.

About the army please lets not have either tragedy or Heroics because they are equeally distastful to me. I went into this perfectly cold bloodedly and dont sympathize with the

“Give my son to country”

ect

ect

ect

or

“Hero stuff”

because I just went and purely for social reasons. If you want to pray, pray for my soul and not that I wont get killed—the last doesn’t seem to matter particularly and if you are a good Catholic the first ought to.

To a profound pessimist about life, being in danger is not depressing. I have never been more cheerful. Please be nice and respect my wishes

Love

Scott.

Notes:

Katherine Tighe, St. Paul friend of Fitzgerald; she became one of the dedicatees of Fitzgerald’s The Vegetable.

xxx. FROM: Shane Leslie

Nov 26, 1917

2127 Leroy Place Washington

ALS, 3 pp. Princeton University

My dear Fitz,

This letter of good cheer will follow you I hope to Kansas. All good wishes for a bright future literary as well as military. I shall be interested in your novel in verse—it sounds bold!

However there is no form of literature which should not be attempted or concocted before the farce of the Anglo-Celto-Latin civilisation is rung down.

I wish you would stick to your idea of a book of poems.1 I was much interested in those you read to me at the Newman School. Thirty or forty would make a book or livret. Nobody has time to finish a book these days. They are served up scaffolding and design more than complete solid form. Do not let Kansas destroy your soul or rust your pen. We must meet again2

yours faithfully Shane Leslie

Notes:

1 This project and the novel in verse were abandoned.

2 See Fitzgerald's 22 December letter to Leslie in The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, ed. Andrew Turnbull (New York: Scribners, 1963); hereafter referred to as Letters.

xxx. FROM: Father Sigourney Fay

December 10th, 1917.

Deal, N.J.

TLS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Dear Fitz:

As I told you when the lightning strikes one of us it strikes us all. You had hardly left when I got my walking papers, and I am waiting expecting every moment to be told where to take ship. First about your questions: Miss Grace will have your letters of introduction for you when you come East. Second: Your book should be called “The Romance of an Egoist.”1 Or, “A Child of the Last Days.” I think the name you signed to your last letter is a very good name. Stephen is undoubtedly the right first name, and my own name is a very good last one. And the Fitz makes a good bridge, and might very well be there as the Fays were Normans originally. I want you to get a book called “The Three Black Pennies.”2 In fact I am going to send it you. It is something like us the same person being repeated, over and over. The explanation of our case is that we are all a repitition of some common ancestor. The only blood we have in common is the blood of the O'Donohue's. I am sure this man's name was Stephen O'Donohue. Before you get this I will probably be on the ocean. It seems only right and proper that I should be the first of us whose life would be put in danger. Then will come your turn and then Peevie's. I do hope you will write to me the night before we go into action. I hope to see you before that time, for I fancy you will go abroad sooner than you think. When you do, however, face the cannon, that you have two lives to take care of as well as your own, or rather that there is only one life amongst the three of us, and if anything happens to you Peevie and I will probably dry up and blow away. I suppose anybody but you would think this the most utter tosh, but the worst of it is, we all know it is perfectly true. How magnificent Streeter is.3 It gave me a frightful shock when you wrote me he thought me splendid. How can he be so deceived? Splendid is exactly the one thing that one of three is. We are many other things—we're extraordinary, we're clever, we could be said I suppose to be brilliant. We can attract people, we can make atmosphere, we can almost always have our own way, but splendid—rather not. Peevie writes me that he has given over his novel for the present. He thinks he is too young. I quite agree, but the real reason why he couldn't go on was that he wasn't writing about himself. I have had a rise since I saw you. Have been made Major and Deputy Commisioner for Italy. I am going to Rome with a wonderful dossier, and there will be “no small stir” when I get there. How I wish one of you were with me. This sounds like a rather cynical letter. Not at all the sort that a middle aged clergyman should write to a youth about to depart for the wars. The only excuse is that the middle aged clergyman is talking to himself. There are deep things in us and you know what they are as well as I do. We have great faith, and we have a terrible honesty at the bottom of us, that all of our sophistry cannot destroy, and a kind of childlike simplicity that is the only thing that saves us from being downright wicked. Oh, you will be delighted to know that Leslie thinks of you as the Rupert Brook of America. I was no end pleased at that. You assure me that it is not sentiment that makes you want to die in the last ditch. What is the use of telling me that, when I know well enough what it isnt and what it is, too. It is Romance, spelled with a large R, but do kindly remember about Peevie and me, and put off your rendezvous with death as long as possible. Send your next letter to Leslie, 2127 Leroy Place, Washington, D.C. with your picture enclosed, and write soon.

Best love.

Stephen Fitz Fay Sr.

P.S. You remember I told you when you were leaving that if you fell I would make a lovely “keen” for you, but I was so keen to keen that I couldn't wait so I made one for your going away, which I enclose.4 I am sorry your cheeks are not up to the description I have written of them, but that is not my fault.

Notes:

1 The working title for the novel that became This Side of Paradise was “The Romantic Egoist.”

2 A 1917 novel by Joseph Hergesheimer.

3 Henry Strater, Princeton '19, who provided the model for Burne Holiday in This Side of Paradise.

4 Published in This Side of Paradise as “A Lament for a Foster Son, and He going to the War Against the King of Foreign.”

xxx. TO: Shane Leslie

ALS, 3 pp. Bruccoli

Dec 22nd, 1917

My Dear Mr. Leslie:

Your letter followed me here—

My novel isn’t a novel in verse—it merly shifts rapidly from verse to prose—but its mostly in prose.

The reason I’ve abandoned my idea of a book of poems is that I’ve only about twenty poems and cant write any more in this atmosphere—while I can write prose so I’m sandwitching the poems between rheams of autobiography and fiction.

It makes a pot-pouri especially as there are pages in dialogue and in vers libre but it reads as logically for the times as most public utterances of the prim and prominent. It is a tremendously concieted affair. The title page looks (will look) like this

THE ROMANTIC EGOTIST

by

F. Scott Fitzgerald

"The Best is over.

You may remember now and think and sigh

Oh silly lover!"-Rupert Brooke

"Ou me coucha banga loupa

Domalumba guna duma..."

-Gilbert Chesterton --> [Some gibberish from "The Club of Queer Trades"]

"Experience is the name Tubby gives to all his mistakes."

-Oscar Wilde

I’ll send you a chapter or two to look over if you would—Id like it a lot if you would.

I’m enclosing you a poem that “Poet Lore” a magazine of verse has just taken

Yours

F. Scott Fitzgerald

2 Lt. U.S.

Co.Q P.O.Bn

Ft. Leavenworth

Kan.

xxx. TO: Shane Leslie

ALS, 1 p. Princeton University

Co. Q. P.O. Bn.

Ft. Leavenworth, Kan

Dear Mr. Leslie:

This is just a note to inform you that the first draft of the “Romantic Egotist,” will be ready for your inspection in three weeks altho’ I’m sending you a chapter called “The Devil” next week.

Think of a romantic egotist writing about himself in a cold barracks on Sunday afternoons… yet that is the way this novel has been scattered into shape—for it has no form to speak of.

Dr. Fay told me to send my picture that he wants through you. Whether he meant for you to forward it to him or put it away until he returns I didn’t comprehend.

I certainly appreciate your taking an interest in my book… By the way I join my regiment, the 45th Infantry, at Camp Taylor, Kentucky in three weeks.

Faithfully

F. Scott Fitzgerald

February 4th

1918

xxx. TO: Shane Leslie

February 1918

ALS, 1 p. Bruccoli

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Dear Mr. Leslie:

Here’s Chapter XVI “The Devil” and Chapter XIII. I picked it out as a Chapter you could read without knowing the story. I wish you’d look it over and see what you think of it. It’s semi-typical of the novel in its hastiness and scrubby style.

I have a weeks leave before joining my regiment and I’m going up to Princeton to rewrite. Now I can pass thru Washington and see you about this novel either on the seventh or eighth or ninth of February. Will you tell me which of these days you’d be liable to have an afternoon off. Any one of them are conveinent as far as I’m concerned. I could bring you half a dozen chapters to look at and I’d like to know whether you think it would have any chance with Scribner.

The novel begins nowhere as most things do and ends with the war as all things do. Chapter XIII will seem incoherent out of its setting. Well—I leave here Monday the 26th. After that my address will be Cottage Club—Princeton, N.J.

I’d be much obliged if you’d let me know which afternoon would be most convenient for you

Faithfully,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Did you ever notice that remarkable coincidence.——Bernard Shaw is 61 yrs old, H. G. Wells is 51, G. K. Chesterton 41, you’re 31 and I’m 21——All the great authors of the world in arithmetical progression

F.S.F.

xxx. TO Sally Pope Taylor

From Turnbull.

45th Infantry Camp Taylor, Kentucky

March 10, 1918

Dear Sally Pope:

Much obliged for the Easter postcard—I'd have loved to have come down for Easter but as you know we haven't much say as to what we can do and what we can't.

My first novel is now in the hands of Scribner and Co. Whether they'll publish it for me I don't know yet. It's called The Romantic Egotist and most of the adventures in it have happened to me in my short but eventful life. Your mother probably won't let you read it until you're sixteen, Sally, and she's perfectly right. However this is premature as it hasn't been accepted yet.

I often think of you all down there and it's good to think that in this muddled hurly-burly of a world some little corners still preserve their peace and sanity. We're going to be moved from Camp Taylor soon but where we're going I don't know. I'm anxious to get to France but probably won't for a long, long time. Tell your mother to read Changing Winds [by] St. John Ervine. It is anti-Catholic rather, but Rupert Brooke is one of the characters in it and I rather think she'd like it.

I hope you read a most tremendous lot, Sally—you've got a keen mind and just feed it with every bit of reading you can lay your hands on, good, poor or mediocre. A good mind has a good separator and can peck the good from the bad in all it absorbs. My best wishes to everyone.

Love,

Scott F.

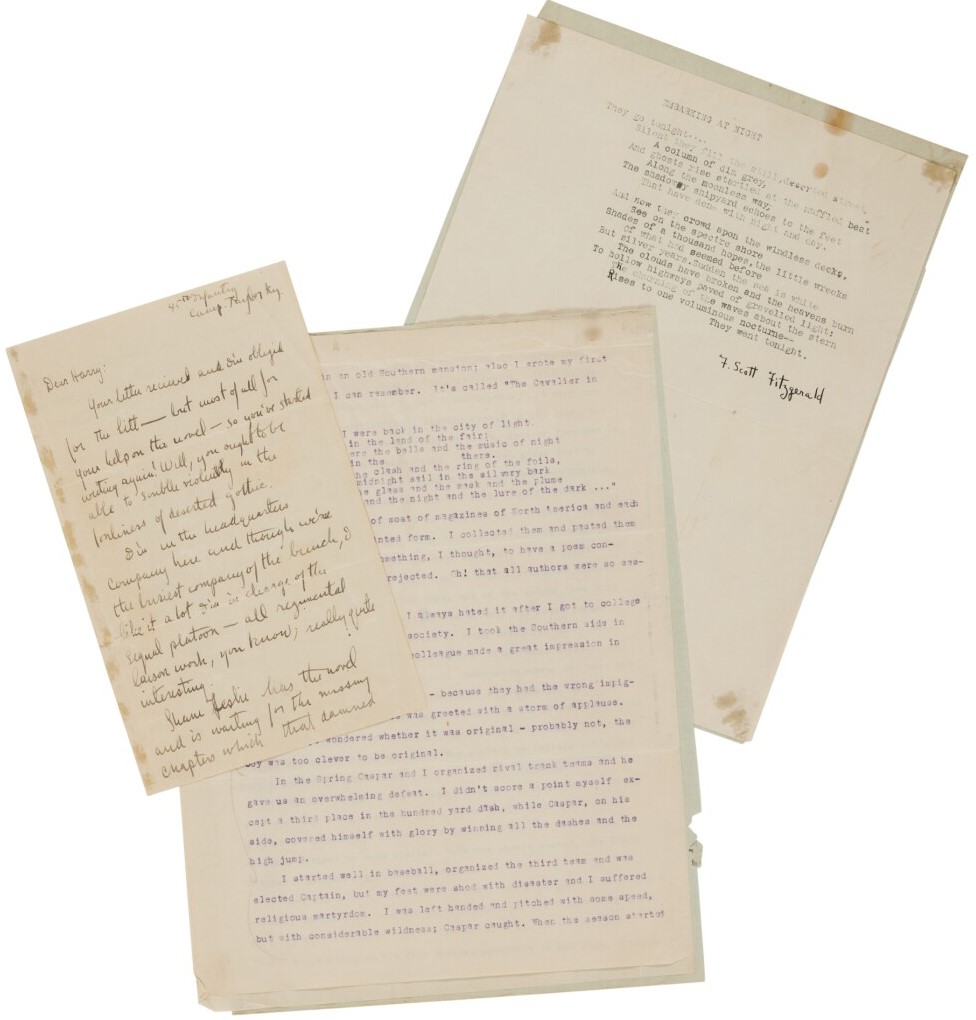

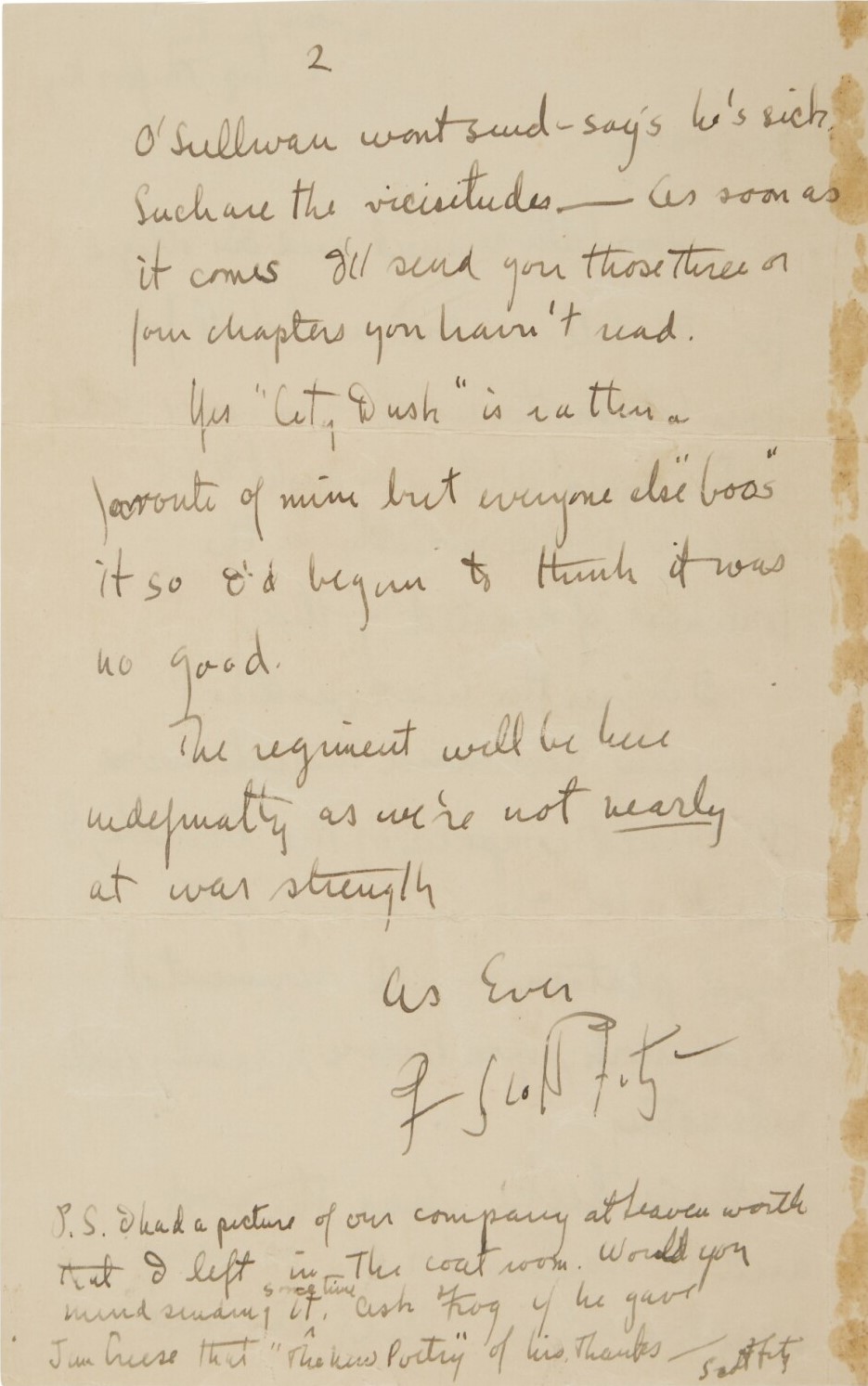

xxx. TO: Harry Keller

ALS, 2 p. plus "Romantic Egotist" TS fragment (3pp) + "Embarking at Night" TS (1p.), Auction

Camp Taylor, Louisville, Kentucky

18 March 1918

Dear Harry,

Your letter received and I'm obliged for the litt — but most of all for your help on the novel — so you've started writing again! Well, you ought to be able to scribble violently in the loneliness of deserted gothic. ...

Shane Leslie likes the novel and is waiting for the missing chapters which that damned O'Sullivan wont send—says he's sick. Such are the vicisitudes [sic] — as soon as it comes I'll send you those three or four chapters you haven't read. ...

Notes:

Harry Keller letter dated 5 March 1918 and sent by Keller to his parents while he was at college:

Scott Fitzgerald since he came down from Kansas for a short furlough after getting his 1st Lieut's commission has been living here at the club working on a book he's been writing there his three months' training in camp. It's an autobiographical novel — and remarkably good & clear & well-written — so it seems to me, after reading most of it through in manuscript. Yesterday he & I got together & spent the afternoon and evening boiling down the first three rambling chapters into one concise one — I read these three and marked out what I thought could be eliminated and then we went over it together and he decided what to cut out — and we got it down to about half its original volume. The rest I've been reading since — sat up til 3 last night with it. If it is published — as it seems probable of being — for Leslie at Scribners likes it and thinks Scribner will take it — I'll feel a peculiar sense of proprietorship in it. It's called 'the Romantic Egotist' — (Scott all over). He leaves tomorrow and probably will sail for France within a month.

Notably, Fitzgerald's letter is sent from Camp Taylor, in Louisville, Kentucky, where he was stationed after enlisting in the army at Fort Leavenworth (the latter also being mentioned in Keller's letter, as he writes that Fitzgerald has come to visit from Kansas).

The present typescript is presumably one of the sections that Keller encouraged Fitzgerald to cut while they edited the manuscript together, and these three pages do not appear in the typescripts of The Romantic Egotist held in the archives at Princeton. As with those, the novel is written in the first person—a change that Fitzgerald would make when he revised the prose that would become part of This Side of Paradise. The protagonist here, as in the other extant typescripts, is Stephen Palms, evidenced on the third page when Mr. Durwent addresses George Lacy (two other characters who appear in known typescripts of the work) and the narrator:

"'I want to say,' said Mr. Durwent, that, that this is no way for anyone to act. I don't know who is to blame, but if scenes like this are to take place, you boys wont be allowed to run your own games. As to this meeting which Caspar Wharton asked me to call, I think we'd better have it another time when you're all calmer and Palms and Lacy can behave themselves.' I was so delighted to hear him include Lacy among the misbehaviors that my wrath disappeared, and when he added that no one could leave the room until George and I had shaken hands, I fairly glowed, and only appeared stern and unrelenting by the greatest effort. ..."

These pages also include within them an unrecorded poem—both This Side of Paradise and The Romantic Egotist featured Fitzgerald's own early poetry, diffused through the writing of his protagonists—which was clearly still in-progress, as it contains what must be unfinished lines. The poem is titled "The Cavalier in Canada," and it, Stephen Palms says, "made the tour of most of magazines of North America and each came back with a printed form ... it was something, I thought, to have a poem considered enough to be even rejected." The poem reads:

Would I were back in the city of light

Back in the land of the fair:

Back where the balls and the music of night

Bask in the there

Oh for the clash and the ring of the foils

For a midnight sail in the silvery bark

Oh for the glass and the mask and the plume

France and the night and the lure of the dark

The archive contains another typescript of a poem, separate from the pages of The Romantic Egotist: "Embarking at Night," which would appear in This Side of Paradise; it was never published by Fitzgerald in its own right, but is a poem of Amory's in the novel. The present typescript contains several differences from the text that appears in the This Side of Paradise, including being written in the third person, along with several entirely different lines. Further, it is corrected by hand in four instances. Given these features, it is exceedingly unlikely that this is either a fair copy or a transcription of the poem by a reader of the novel. The signature below the typescript, however, is dissimilar to most examples of Fitzgerald's own; it may be that the signature is in another hand, attributing the poem to him.

xxx. TO: Mildred McNally

March/April 1918

Military Camp Zachary Taylor, near Louisville, Kentucky

Dear Mid

(Or midsummer or Midnight perhaps)

In the cool of the evening, twixt mess call and taps

The sage grey haired Matty has hailed me “Hey You!”

As he struggles composing a letter or too

And informed me that Mildred the light of his heart

(Whose nose wears no powder who eye brows no art)

Would like to recieve with his bi-weekly note

A poem his brilliant assistant has wrote

(Bad grammar, excuse me I’m crude but I’m cute

And clever and rather good looking to boot)

Well, Stranger, here goes: I am well known to fame

As F. Scott Fitz - Wait! I cant tell you my name

Matty specified this and I had to agree

Lest you transfer your fickle affections to me

Are you dark? are you fair? are you languid or fat?

A pencil brunette or an elderly cat?

Are you mild or “a scream”? quite a wit or a loon?

Do you dress in pale lilac or savor maroon?

Wear Djer Kiss or is there about you a trace

Of that whats-its-name powder that sticks to the face?

Do you smoke, do you read, can you vote, do you swim?

Did Matty abduct you or you capture him?

You see I’ve no dope & I’m a young second lieut

And he is a first, my commander to boot -

And when he whispers “write” (he gets harsh now and then)

I growl, grouch and mutter - and pick up my pen

Now this [is] a secret - its Mathieson’s shame -

He’s afraid lest I tell you my honestly name

Because such a Romeo Brummel as I

Am rather a lure to the feminine eye

So poor incognito I write in my mask

(Is it not just as bad as a gas one? I ask)

And scorned and unknown I splutter and think

As syllables, syllables flow into ink

You think I’m concieted, I’ll bet you are vain

You think I sound silly, I’ll bet you’re inane

You think I’m too fresh — well you’re too overdone

Childish you say — but your just twenty one

Twenty one — Twenty one, you and I, just alike

If I had one I’d give you a ride on my bike

If I knew you I’d love you or hate you or: wait

Perhaps be indifferent and use you as bate

So Mildred don’t cry, you are weeping I’ll bet —

Perhaps it is better we never have met —

No doubt we were made for each other, my dear

But the Lord made the world and Mathieson’s here

To take the most gorgeous queen bees from the hives

And change them to horrible dutiful wives.

I hear you’re a Catholic, so’m I, and I hope

You pray to the saints but don’t worship the pope

Except when we speak ex cathedra (to the crowd)

I’m afraid he’s pro-German (don’t breathe it aloud)

While Matty is struggling and tearing his hair

For me its a cinch just because I don’t care

But then I’m a genius, its pleasant but its

Quite a bore my dear Mid

Yours quite faithfully

Fitz

xxx. TO: Shane Leslie

RTLS, 1 p. Bruccoli

45th Inf. Camp Gordon Ga.

May 8th 1918

Dear Mr. Leslie:

Your letter filled me with a variety of literary emotions… You see yours is the first pronouncment of any kind that I’ve received apon my first born… …

That it is crude, increditably dull in place is too true to be pleasant… I have no idea why I hashed in all that monotonous drivel about childhood in the first part and would see it hacked out like an errant apendicitus without a murmer… There are too many characters and too much local social system in the Princeton section… . and in places all through the verses are too obviusly lugged in… …

At any rate I’m tremendously obliged for taking an interest in it and writing that awfully decent letter to Scribner… If he thinks that a revision would make it at all practicable I’d rather do it than not or if he dispairs of it I might try some less conservative publisher than Scribner is known to be…

We have no news except that we’re probably going inside of two months—and, officers and men, we’re wild to go…

I wonder if you’re working on the history of Martin Luther or are on another tack… Do write a novel with young men in it, and kill the rancid taste that the semi-brilliant “Changing Winds” left on so many tongues. Or write a thinly disguised autobiography… or something. I’m wild for books and none are forthcoming… I wrote mine (as Stevenson wrote Treasure Island) to satisfy my own craving for a certain type of novel. Why are all the trueish novels written by the gloomy, half-twilight realists like Beresford and Walpole and St. John Irvine? Even the Soul of a Bishop is colorless… Where are the novels of five years ago: Tono Bungay, Youth’s Encounter, Man Alive, The New Machiavelli… … Heavens has the war caught all literature in the crossed nets of Galesworthy and George Moore…

Well… May St. Robert (Benson) appear to Scribner in a dream…

Faithfully

F. Scott Fitzgerald

P.S. much obliged for mailing on Dr. Fay’s letter

F.S.F.

Notes:

Changing Winds (1917) was by St. John Greer Ervine.

John Davys Beresford, Hugh Walpole, and Ervine were contemporary British novelists.

The Soul of a Bishop (1917), Tono-Bungay (1909), and The New Machiavelli (1910) were by H. G. Wells; Youth’s Encounter was the American title for the first volume of Compton Mackenzie’s Sinister Street (1913); Manalive (1912) was by G. K. Chesterton.

John Galsworthy and George Moore were realistic British novelists.

Benson, son of an Archbishop of Canterbury, converted to Catholicism.

xxx. FROM: Shane Leslie

Washington May 11, 1918.

ALS, 2 pp. Princeton University

My dear Fitz

I read your book with real interest devoting thereto a whole Sunday. It will stand as it is very well and if there are to be operations I will see them through.1 So you may depart in peace and possibly find yourself part of the Autumn reading banned by the Y.M.C.A. for use among troops! Let me know before you depart. Fay's last letter seemed to point to his return this month but he is far too useful in Rome where an American lever is needed to switch Austria on to President Wilson's policy.

By the way the Pope has made him Monsignore and clothed him in purple from thatch to toe. I hope we all meet again before the world is over—

Yours ever Shane Leslie

Notes:

1 Leslie sent Fitzgerald's novel to Charles Scribner with a covering letter that read in part: “I have read it through and in spite of its disguises it has given me a vivid picture of the American generation that is hastening to war. I marvel at it's crudity and its cleverness. It is naive in places, shocking in others, painful to the conventional and not without a touch of ironic sublimity especially toward the end. About a third of the book could be omitted without losing the impression that it is written by an American Rupert Brooke. I knew the poetic Rupert Brooke and this is a prose one, though some of the lyrics are good and aparently original. It interests me as a boy's book and I think gives expression to that real American youth that the sentimentalists and super patriots are so anxious to drape behind the canvas of the Y.M.C.A. tent. Though Scott Fitzgerald is still alive it has a literary value. Of course when he is killed it will also have a commercial value. Before leaving for France he has committed it to me and will you in any case house it in your safe for the time? If you feel like giving a judgment upon it, will you call upon me to make any alterations or perform whatever duties accrue to a literary sponsor?”

xxx. TO Sally Pope Taylor

From Turnbull.

45th Infantry Camp Sheridan, Alabama

June 19, [1918]

I did enjoy your letter, Sally, and I believe you're going to be quite a personage. A personage and a personality are quite different—I wonder if you can figure the difference. Your mother, Peter the Hermit, Joan of Arc, Cousin Tom, Mark Antony and Bonnie Prince Charlie were personalities. You and Cardinal Newman and Julius Caesar and Elizabeth Barrett Browning and myself and Mme. de Stael were personages. Does the distinction begin to glimmer on you? Personality may vanish at a sickness; a personage is hurt more by a worldly setback. Of you four sisters, you and Tommy are personages, Celia is a personality and Virginia may be either—or both, as Disraeli was.

Do you know, Sally, I believe that for the first time in my life I'm rather lonesome down here—not lonesome for family and friends or anyone in particular but lonesome for the old atmosphere—a feverish crowd at Princeton sitting up until three discussing pragmatism or the immortality of the soul—for the glitter of New York with a tea dance at the Plaza or lunch at Sherries—for the quiet respectable boredom of St. Paul.

What a funny way to write a girl of thirteen, or is it fourteen?

Thy cousin,

Scott

xxx. FROM: Monsignor Sigoumey Fay

Deal Beach, New Jersey

August 17th, 1918.

TLS, 2 pp. Princeton University

Dear Fitz:—

If I were accustomed to being affectionate with you this letter would sound like a letter of Mrs. Fay to Michael. I always think it such a shame that your very American training makes it impossible for me to pour out my paternal affection to you like I do to Peevie, for whom I notice you have the truly elder brotherly low opinion. I assure you he is not shallow, unless you and I are also, and he is becoming a very worthy member of society spending the summer in great discomfort at the Widow Nolan's at Cambridge tutoring diligently for the Tech. I have seen quite a good deal of him since he has been in the East, as he came here to Deal and also spent a Sunday with me at Southboro while I was there. We also had luncheon together, and tea at another time in Boston.

But the question which interests me at this moment is, when do I see you? You spoke of leave in August. I shall be here until the 30th. His Eminence and the Bishop of Richmond are staying here with me, and it is very hard to get a moment even to write, but I wish you could come if only for a week-end; or if you could come in September it would be even better. Or, again, if you could come as far as Washington in September I will go down and meet you. I have ten thousand things to say that I cannot write. There are intimacies that cannot be put upon paper.

The two chapters of your novel which I read gave me a queer feeling. I seemed to go back twenty-five years. Of course you know that Eleanor's real name was Emily. I never realized that I told you so much about her. It was Swinburne, however, not Rupert Brooke, that we used to read together. How you got it in I do not know; her materialism and the preternatural circumstances—unless it is possible that you inherited my memory with the rest of my mental furniture. Really the whole thing is most startling; I am keen beyond words to read the rest of that book. I may be frightfully prejudiced but I have never read anything more interesting than that book. I think it beats Youth's Encounter hollow, if only in the brutal frankness in the use of the first person. There is always something far more arresting about a self revelation than there is about a story told about somebody else. If the rest of the book is up to the two chapters I have read it must be a corker. I suppose this is most ill-advised talk on my part, but really I cannot be bothered with the hypocracy of an elder damning with vain praise nor […] my really great enthusiasm.1

Leslie told me himself that Scribner liked your book extremely and was reading it himself. I cannot understand their having told you that Scribner had not seen it. Do let me have the rest of the novel right away. I will read it quickly and send it back.

What a tremendous role the actual and cold fear of Satan does play in our make-up, and what a protection this sort of sixth sense by which we sense him, to use an American expression, is.

I am sorry you are in trouble again, but glad that at last you have time to remember my existence and to write to me.

Do write to Peevie. He is most anxious to correspond with you, and would really be a delightful correspondent, and you can speak quite as freely to him as you do to me. I should think you would find it rather fun to write to him as an older person to a younger, and to me as a younger person to an older. Youth and age both have their compensations.

What I shall do in the future is hanging rather in the balance, but I expect it will end in my going back. I wish the war were over and that I had a house in Washington, that you had digs in New York or somewhere near and could drop in for week-ends, and that Peevie were at a university. This war could very easily be the end of a most brilliant family.

Do try to get leave and come up to see me; and, above all, send me the rest of that book.

With best love,

Stephen Fitz Fay Sr

Lieut. F-Scott Fitzgerald, Hq. Co. 67th Infantry, Camp Sheridan, Alabama.

Notes:

1 The space in this line appears in the original.

xxx. FROM: Monsignor Sigourney Fay

October 19, 1918.

Baltimore, Maryland.

TLS, 3 pp. Princeton University

1st. Lieutenant Scott Key Fitzgerald, 67th Infantry, Headquarters Company, Camp Sheridan, Rifle Range, Alabama.

Dear Fitz:

I hasten to send back the parts of your novel which you were good enough to let me read. The more I see of it the more amazingly good I think it is.

I wish you hadn't called me Taylor.1 In fact I seem hardly to be like myself at all as a lay diplomat, and I do think a one syllable name is almost essential. Taylor gives a quite wrong impression,—Forbes, or something like that I think would be much better.

Besides I don't think my conversation sounds a bit like myself. The following bit of dialogue would explain what I mean:

“Have you got anything there I should like?”

“Do you like milk?”

“Rather.”

“I have got crackers and jelly too, the jam is all out.”

“Right. I think jelly is ripping, don't you?”

***

“Good Evening, Sir,” I said uncertainly.

“Good Evening,—lets see the grub.”

The rest is alright until you come to—

“Well” he said at length, “thats A-1.”

The moon came out and we looked at each other unembarrassed.

“I say, you know” he said “you are a very unhappy boy aren't you?”

“Oh, well you look as if” etc.—“are there any more biscuits?”

“No, Sir.”

“Well then, I'll cut along.”

I do hope you can get to New York soon. There are about a million things that I cannot write about that I want to say to you, and when you come you must arrange to spend two or three days, as it is going to take forty eight hours to tell you all about last winter.

I think your book is way and beyond “His Family” or “The Harbor,”2 or any of those self revolation sort of books. It is really very like “Youth's Encounter.”

McKenzie has written a new book, “Sylvia Scarlet.” You remember Sylvia in “Sinister Street.” He has just simply taken Stella Fane gone wrong, and in order to excuse himself he has made her also a descendant of Lord Saxby. I think he has run out, Poor Michael is a proven ghost in this book, all the insides have gone out of him. As a matter of fact he cannot write the third volume of Michael's life. When I go to Europe I mean to get to know him and talk it out with him. In the meantime I am perfecting a sort of scheme which I will never publish without his permission of course.

The scheme is a collection of Michael's letters from Rome while he is studying and after he has been ordained, a diplomat in the service at the Vatican. I shall call them “The letters of Monsignor Fane.” I felt a tremendous desire to do it lately.

With best love,

Stephen 1st

P.S. I have seen a lot of Peevie, who is at Harvard in the O.T.C. Peevie would have yelled at the idea of my writing anything for him. He says writing is your flare, architecture is his, and music is mine. But I tell him I could write if I chose, be an architect if I chose, and both of you could be musicians if you like,—so.

With best love, S 1st

N.B. Our letters are not at all what they ought to be, but I have been minus a secretary for a long time, and when on the rare occasions I can get one a lot of correspondence has piled up, and I never get a chance really to speak my mind. I think when we write one another, we ought always to think of the possibility of the other person some day publishing that letter.

S 1st

I have returned your letter as you said it was part of your novel

S.W. F S 1st Stephen Fitz Fay Sr.

Notes:

1 The name Taylor was changed to Darcy in the published novel.

2 Novels by Ernest Poole published in 1917 and 1915, respectively.

xxx. FROM: Charles W. Donahoe

Sunday Oct 27, '18.

Trade Test Dept. (Alias Somewhere in France Camp Lewis, Wash.

ALS, 4 pp. [Published only the first page and a half of this letter discussing Fitzgerald's novel], Princeton University

Dear Fitz:

Lost your address so am taking a chance on this reaching you. Received the three installments or chapters of your story and was very much interested in reading it. Recognized practically all the material of composition but as the well known WW3 says “I would deem myself lacking in candor” did I not say that I was distinctly disappointed in your handling of the material “Nothing can be gained by leaving this essential thing unsaid.” You remember in Stalky & Co the reference to St. Winifred's or the World of school and “Eric”4 Well I have read Eric and realize, as you would, what spirit Kipling objected to in Eric. Think your book is very much an American “Eric.” Of course I realize how damn hard it is to make the humorous scenes humorous, the serious ones serious and so on, but think you have failed entirely in getting it across as well as you could do had you taken more time. For instance the description of yourself hiding behind the rug when Dr——came in the room. Also you have given a description of Princeton which while accurate enough overemphasizes the social climbing drinking etc. You have left all the fun out of it. Your description of the wrestling match with Izzy Hirsch fell rather flat. Your use of specific names of clubs etc is not going to be appreciated in the sense you have used them. Owen Johnson's5 use of “Bones” was different. Everything seems have been skipt over the work is done too fast. There is none of the “je vous gloterai” spirit of “Stalky & Co.” Think you could do ever so much better if you took more time and care. Noticed you placed JPB in the same position as Guy——in Sinister Street (the one who was hero of Plasher's Mead 6)

Notes:

3 President Woodrow Wilson.

4 Rudyard Kipling's Stalky & Company (1899); Frederic W. Farrar's Eric (1858) and St. Winifred's (1862).

5 Author of Stover at Yale (1911).

6 A 1915 novel by Compton Mackenzie.

xxx. TO Ruth Howard Sturtevant

From Turnbull.

67th Infantry Camp Sheridan, Alabama

1st of Winter Nineteen hundred and Eighteen

[Postmarked December 4, 1918]

Dear Ruth:

Just a line to tell you how much I enjoyed Sonia—If you like that sort of book you should read Youth's Encounter (Mackenzie), Changing Winds (Ervine), and The New Machiavelli and Tono Bungay (H. G. Wells)—

My affair still drifts1—But my mind is firmly made up that I will not, shall not, can not, should not, must not marry—still, she is remarkable—I'm trying desperately exire armis—

As ever, Scott Fitzg——-

Notes:

1 Fitzgerald had made Ruth Sturtevant a confidante in his romance with Zelda.

xxx. TO: Ruth Howard Sturtevant

Early 1919

Montgomery, Alabama

ALS, 1 p. [The Letter written in slanted sections covering the paper], University of Virginia

The Sunny South

Ruth

I am in love! Happy New Year!

You made a great impression on ma jeune soeur—Isn't she stoopid—

I am now aide-de-camp to General Ryan—Sweet is it not—

Ruth—I'm so glad we like each other again, or am I presuming?

I hope to Appollo

I'll be out in April—

I'll probably be out before

my book at that2

I beg to remain

Your obediant Servant

Geo Washington

Notes:

2 “The Romantic Egoist” was declined by Scribners; it was not accepted until September 1919, after Fitzgerald rewrote it as This Side of Paradise.

xxx. TO C. Edmund Delbos

From Turnbull.

17th Brig. Headquarters Camp Sheridan, Alabama

January 13, [1919]

Dear Mr. Delbos: