Fitzgerald Attends My Fitzgerald Seminar

By Vance Bourjaily

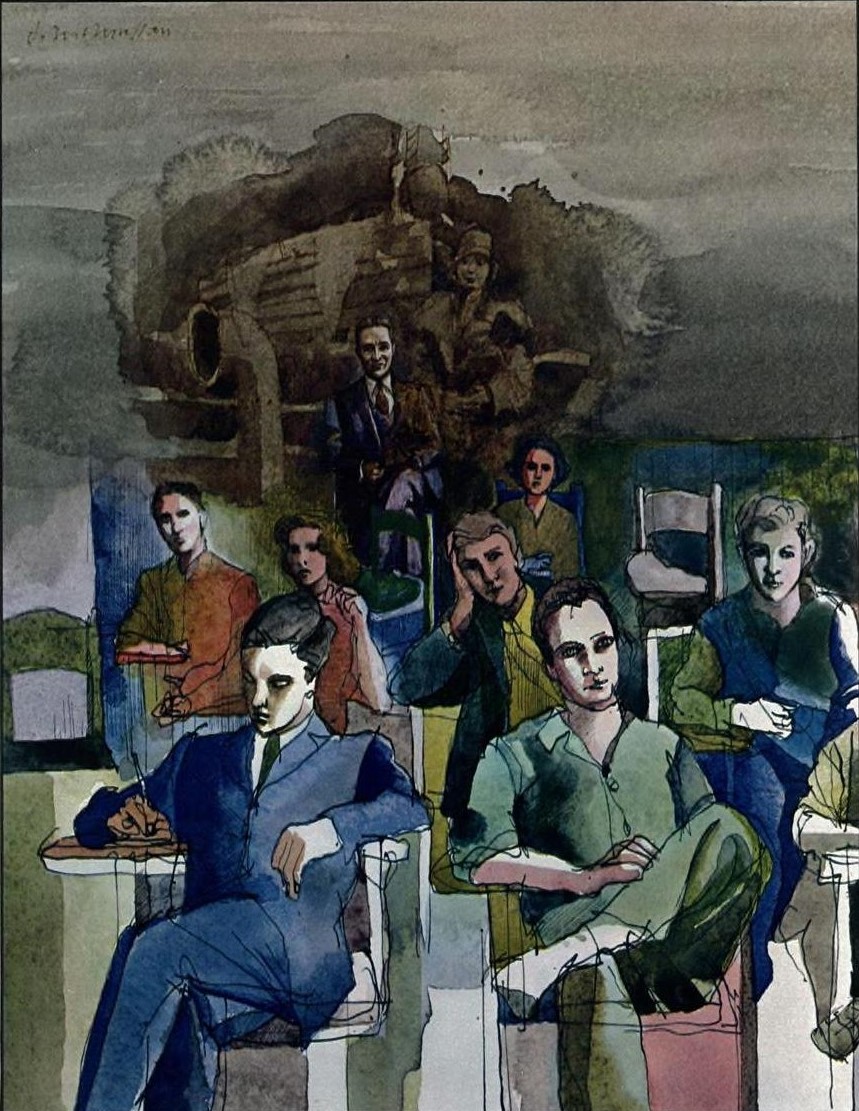

There sit the students of 1964, here stands their teacher—and back there, in the rear of the room, sits Scott himself; listening eagerly, at first, and thinking God knows what.

It is a frequent, not a favorite, fantasy of mine (Professor Short said) that one Tuesday afternoon when I arrive at Building UTBF to teach my graduate seminar in the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, he is there—a pale, nominally handsome man, waiting for the class to start. He sits, I imagine, facing the desk where I will sit, as if he were to be one of the students, in the next-to-last of the five rows of seats in my small plain classroom.

Two of the dozen graduate students enrolled in the course are already there as well, a neatly dressed boy. a tall girl, who came together. We are all three (all four) a little early.

“Hello, Mr. Short,” says the boy, whose name is Miles Hubbert, and the girl smiles blandly.

The intruder—well, the auditor. The auditor has placed himself as far away as is tactful from the student pair: not in the farthest seat left (left as I will face the class), but one chair in from that final, outside row. I have noticed that students in a small classroom always tend to group toward my right, and I wonder if he didn't realize this when he chose his place.

I knew who he was at a glance, of course, though my student pair, as well as those who will be along in a few minutes, may not. They are less accustomed than I to pondering those photographs: seeing him. I wonder again if the word “handsome” would have attached itself to this man had he not himself asserted that such was his appearance.

I am speaking, you understand, only of the appearance ns pictured: I was sixteen when he died, and never actually saw him, nor is there any reason why I should have. But the man in the photographs has never seemed a handsome one to me. A masked man, rather, even in that young picture where he and Zelda and Scottie are all kicking out their feet in a dance step—the mask is debonair, merry, appealing, saved from smugness only in being somehow tentative, but only ordinarily good-looking. The bones which stretch the mask are grave bones, and their marrow is pain. Or is this the aftersight of anybody brought up on America’s Monday morning? No matter. Surely one would rather look like, say, photographs of the young Hemingway. As one would rather look like Clark Gable than—could I cite these to my students? Hardly—Leslie Howard or Lew Ayres. (Not, no, that I look like any of these: in my photographs I think that I look bright-eyed and appalled, like a raccoon caught in the headlights of a car.)

As I turn from behind the desk my eyes meet his (not a raccoon’s but a wild bird’s): he seems to be asking me not to make known who he is. I could not refuse him anything, not today anyway, for he looks ill, incipiently middle-aged, drawn, painfully sober—but less out-of-place than you might think, sitting in a scratched-oak classroom sent with armrest for writing. Yes, he could be such a curious older visitor as we sometimes have—someone from another department of the University, an out-of-town guest of mine—to the students’ incautious human eyes. They will register white shirt and quiet tie, but not the odd cut and wrong color of his business suit; it is the grey flannel which did not become unfashionable until I myself was in an Ivy League college, in the padded cut of the Late Depression. By it I know which period he is in—post-Crack-Up. Hollywood. The Last Tycoon, Budd Schulberg. Sheilah Graham. Arnold Gingrich. The last month. He is already, fatally forty-four. The final period.

Immediately I am confused at thinking of him in this way, confused because though it feels cold to me, I concede that he might like to contemplate the Institutionalizing of himself that the division into periods connotes. In the twenty-three years since he died, this way of describing his life as if it were merely a career has become a convenience universally used by teachers and their students. There is not a youngster entering who could not (and as the most obvious kind of literary information) tell you the order of publication of his books, describe the critical and popular reaction to each one, and tell you how things were going for him when he wrote it. Yes, it would likely please him: it's a kind of attention which he died believing he would never get, nor even merit. Yet only six more years—all he'd have had to do was get past fifty, as Hemingway and Faulkner did. to see the processing start up: an emotional preface here, an M.A. thesis there, brief learned articles, larger ones, fictional treatments, studies at the doctoral level, whole books: an American becomes subject matter.

Four more students are seating themselves. Petey Luther among them: I wish this particular bright, harsh boy—my best student—had cut today. I hear his impatient voice arguing and it causes me such alarm that I suddenly consider dismissing the class. Fitzgerald and I could get a beer. Well, no, some coffee, I suppose. Yes, fine, Mr. Short. Just what he's come here for, the privilege of watching you drop saccharine tablets into bad coffee. And would you offer him a Hershey bar? The condemned man’s last meal retasted (it was a Hershey bar, you know, that Sheilah Graham reports she gave him when he asked for something sweet, sitting there calmly in the Hollywood apartment, reading The Princeton Alumni Weekly, a few minutes before his heart quit).

(Almonds? That was a prep-school joke: male or female Hershey? I suppose he must have known that one. Ah, footnote writer, ah, diseased, ah, ghoulish, ah. Short, what a grand fellow and wise teacher the world has in you.)

“Will it disturb you if I attend today, Professor?” He asks it softly, placing his question under the clamor of youthful statement. His voice is cultivated, easy, touched with a protective whimsy to make it possible for me to say he must leave. From this, I can guess that it is not my teaching of his work that he has come to hear, but what the young men will say. How could I not have known it?

“You'll be very welcome.”

“But if you'd rather I left?” Painful courtesy, extending the anxiety of his moment, for it would destroy him were I to say. Yes, go.

“Please stay.”

The students pay very little attention to this quiet conversation, for they are having a loud one of their own—a real, bickering. I-know-his-goddamn-batting-average-better-than- you kind of conversation about George Orwell’s Burmese Days. Petey Luther thinks it’s the finest novel of the twentieth century. Kevin Candlekirk, tricky debater, is leading the Luther kid on:

“Don't you think British Colonial matters are a little old hat? That’s a topee, of course—Maugham’s old pith helmet. Conrad’s white cork.”

“Yeah? Pith on you. Candlekirk.” says Petey.

“Orwell was an officer, wasn’t he, Petey?”

Such classroom manners, and with girls present, have startled my auditor, ending our own small discussion. Only the first boy, Miles Hubbert, has followed it, and he looks at the visitor rather closely. I have seen Hubbert on campus several times recently with this same tall, bland girl. (She is not his wife. She has a magnificent figure. She does not belong in my course. She is vapid.) Hubbert looks at me, and back at the pale man so seriously, with such open curiosity, that: no, even if he did do his undergraduate work at Princeton. I shall not let him guess. Hubbert, by the way, has three children, back in a Quonset hut across the river. Before the tall girl, whose name I can't yet remember (it is still early in the semester, the third class meeting, but now I do remember it: Betty Cass Collins), before that, Miles Hubbert used to be seen on campus with a cute, medium-tall girl called Janssy. I enjoy Janssy, who has taken a number of my courses, and would have expected her to be in this one. I feel that Hubbert is to blame for her not having registered for it. He must have changed extramarital girls just about registration time. Since his contribution to a class session is to listen aloofly for two hours, not quite smiling, saying nothing. I resent him just a little. Two hours is a long time to keep things going, and an alert, pretty girl like Janssy is a great help. Hubbert’s new girl (Betty Cass Collins; why Cass for Christ’s sake?) is as quiet as he is; but not like he is; the quietness of cows is not like that of foxes.

“Who’s asking you to repudiate Orwell?” Kevin Candlekirk cries, still teasing Petey Luther. “All I'm asking you to do, leaving Orwell out of it, is to name one first-rate novelist, just one, who was also a first-rate thinker? How about Dostoevsky, say, on politics? Or religion?”

“All right, he was a bum. Does that make Camus into a bum, too?”

“No. but it doesn’t make The Stranger into War and Peace, either.”

“What about Joyce?” Petey’s tone isn't really angry, but if you didn't know him you might think it was.

“I don't think I’d want Joyce to marry my sister.” Kevin says, and they all laugh, even Petey; but not Miles Hubbert, who only smiles slightly. And not the cow-girl, who cannot be presumed to have understood.

I glance at the auditor and see that the irreverence both pains and excites him. Joyce was a hero to him.

“We’ll wait a minute or two.” I announce. Petey and Kevin look at me, startled. I suppose, at the nervousness in my voice. “For the others,” I explain. “The rest.” My students are not prompt. Nevertheless, all are here, probably, who will be—eight out of the twelve—except for a girl named Eartha Hearn who is characteristically the least prompt and the most eager to be on time. Eartha has a paper due today and will wheeze in, distraught, apologetic, from a useless run through the parking area outside which I will wish she had spared herself. And here she is, hesitating at the door now, panting—smart, disheveled, overweight Eartha—and another girl behind her? Yes. Yes, by God, it is; Janssy!

“Professor Short,” Janssy sings, gaily and all in a rush, pushing past Eartha Hearn and standing, legs open, on the balls of her feet, pink hand on the desk, leaning at me. “I registered late. Okay? I mean. I read This Side of Flapdeedoodle and Petey and Kevin told me what you said and they said, and the book for today, so I'm all caught up and I've even got a surprise, okay?”

I wince at Flapdeedoodle. I cannot see past her to know if he does. She blocks the view with soft sweater under open corduroy overcoat, and I can’t speak. I have always liked to look at Janssy and whether she knows this or not. she does know that I’ll agree to let her join the course. I nod, cannot speak, and try again to look past her at the pale man.

“But you have to sign my slip.” she scolds and smiles and leans, all high coquetry, as a girl might demanding a kiss in public.

“After. After class, Janssy.” I say, and she tilts her head, executes a ravishment, and slips into a sent by Kevin and Petey, ignoring the vacant one by Eartha Hearn with whom she came in. Nor does she look at Miles Hubbert, her former—what: lover, boyfriend, escort? Hubbert’s face registers nothing more than its usual amused caginess.

“Let’s settle down, please,” I say, more crossly than I mean to. “We have a lot to cover.” Kevin’s hand goes up. “Yes. Kevin?”

“Something from last week,” he says.

“All right.”

“Just for perspective. We were talking about This Side of Paradise as if it were an undergraduate's novel,” he says. “As if Fitzgerald were some kind of boy wonder. But look, he was twenty-three. Grad-student age, not a college kid. He'd been in the Army already. He’d even written one book and had it turned down.”

“Yes.” I say. “Of course. But you realize this was the same book, don't you? With a new title and some further revision. A good deal of it had been done while he was still at Princeton. As we were saying, portions of it had actually been printed several years earlier, in the Nassau Lit.”

“So much the worse, though, wouldn’t you say? I mean, can you imagine a real boy genius like Rimbaud having the kind of ego where you’re going to reuse everything you ever wrote, instead of the other kind of ego where you keep tearing it up, and striving for something perfect?”

“He didn't need Edmund Wilson.” Petey Luther says. Apparently he and Kevin have been rehearsing this. “He needed a wastebasket.”

I hardly dare look at the visitor, but I do. He seems—oh, quizzical, I suppose. Realizing that the young are never generous in making allowances for youth. Very well, then. I will be tactically cautious in opposing class opinion for the moment: I will wait for a better opening. Inter in the period.

Still, I must establish that concession is not to be my posture at any point today, so I say: “You know, a novel’s a good deal harder to throw away than a poem. It’s several years of work, not just a few days. And remember, the form itself, the novel, as an American expression shaped to the times, wasn't all laid out for him as it might be for one of you. It still had to be developed, it had to go through the hands of men like, well, like Fitzgerald himself as he was when he got done with Gatsby.”

“Anyway, Petey,” says Janssy, “different people mature at different ages.”

“You were speaking of perspective.” I say. “Perhaps it would be better to come back to this point later in the course.”

“Rimbaud was probably a boring old man at twenty-three,” the girl insists, and obviously this is for Miles Hubbert to hear. “Who'd want him?”

“Let's get to today’s work,” I say, but then I am reluctant to say what comes next. I know the visitor is going to be dismayed, but there is no way around it. I avoid looking at him and stare at bland, blonde Betty Cass Collins: there are two sorts of girls one looks at in class; the Janssy’s, whom one enjoys looking at and forgets; and the Betty Casses, whom one sees with irritation, but whose coeducated bodies and sorority-group faces stay on in the mind. You feel you could do anything with such a girl, not because she seems sensual, but because she seems stupid. What bland blendings with blind blonde, bluntly—yes. Short. And sometimes you realize that an aura of such stupidity is something they wear to attract, like perfume, and means as little.

I continue to stare at Blah Cuss Cullings, and say what I have to say:

“Today, as you know, we will discuss the second book, the short-story collection, Flappers and Philosophers.” But neither the clear-skinned, alphabetaface nor the unsuggestive knees of Miss Collins can hold my eyes away from his: they are stricken, the bird shot down. Why, on his only visit, must we talk about the least of his books? Why can we not be celebrating the great, achieved works, Gatsby and Tender Is the Night? Or discussing the tragic self-appraisal of The Crack-Up, in which everything is revealed but the one essential thing: how does genius survive the remorseless plots it makes against its own fulfillment? Hell. The Last Tycoon or even one of the other story collections…

“Yes, Eartha?” It is odd about this bright girl, with her good mind and bad teeth, that she alone raises her hand when she wishes to speak, and will not begin until recognized. The rest, in my undisciplined class, push their way in and out of discussion at will. New York manners. Where were you brought up, in a subway?

“Yes. Eartha?” But Eartha Hearn is from New York, and is polite: Janssy from a little town in Illinois, and steps on my feet whenever she feels it’s her stop. Petey and Kevin are New York boys, true to type. Miles Hubbert? The East. I do not know where cow-girls come from, only that any time one goes away, another comes.

“Yes. Eartha?” There are others in the class, as indicated, but let them stay out of focus; they will get their C-pluses and B-minuses when the time comes. “Yes?”

Have I said, “Yes, Eartha,” once or four times? Does the visitor sympathize with my uncertainty, or hold it in distaste? But I’m a scrapper, Scott, really I am, capable of rudeness too—no. No. Ten years of practice in academic manners and the false tolerance for other views which covers up uncertainty, to obtain unchallenged comfort for my family (the Professor’s little daughters may play on even terms with doctor's children here), stand between this present and my scrapping days. I have become a fraud, who risks nothing but a hopeful good humor and a restraint which permits many impositions.

“Professor Short, about my seminar paper.” Oh boy. Here we go. Eartha’s excuse for not having done on time the paper that she’s supposed to read here today. Some unanswerably drab female medical excuse. I suppose. And then what shall I do with two hours? Lecture? Without notes? Well, maybe—yes; yes, it could be best, at that. For me to lecture, spontaneously, out of the feeling I have, letting the words and ideas come as they will—this is something I haven’t done since my instructor days when, sometimes, I was so full of a subject (yes, in a sophomore lit survey course, even there, talking about Tom Jones or The Scarlet Letter!)—so full of it that notes would have been too confining, a hindrance. Hooray for menses, I will save the day.

“Professor, we made a change,” Eartha says. “If it’s all right?”

I frown, insincerely.

“I mean. Janssy wanted to share doing the paper with me. So I have a general paper on the book, and she’d like to talk about one particular story, afterward. I mean, since she’s just joined the course? And…”

Oh, all right. Let Janssy save the day, then. The girl’s always been a bear for extra work. All right. I find a smile somewhere and present it. “Which story will it be, Janssy? Bernice Bobs Her Hair?” The best story in the book in many ways; the auditor has a smile, too. But Janssy shakes her head. “The Cut-Glass Bowl?” A failure, but interesting for its ambition. Janssy smiles, and shapes a “no” with her shiny lips. Three guesses, is that what we're playing? Very well. The Ice Palace is a good story, and Benediction very interesting indeed—which of these two?”

“The Offshore Pirate, Mr. Short,” Janssy says.

“For heaven’s sake, why?” There are worse stories in the book—exactly two of them.

“I think I can show that it’s important,” Janssy says.

“Oh, come on Janssy,” says Petey Luther.

(Do you know that story? About a flirt on a yacht, which is boarded by a young man who represents himself ns a rebel and fugitive, bringing along his own jazz band? And woos, and finally discloses that he’s top-drawer eligible, just like her—oh hell. It’s preposterously bad.)

The auditor’s face is with me, all the way, and yet resigned, disturbed und resigned to whatever bumptions the young will inflict us with.

I nod to Eartha Hearn that she is to go ahead.

Her paper, which she reads carefully and not quite loudly enough, is what I have come to expect from her: thoroughly researched, critically conventional, a dull A. Yet last week I hoped: so often, when one is finished talking over with a student what he or she means to do in a paper, one docs hope. The things they say they want to write (“Perhaps try to get at what the flapper personality really was, was it different from a flirt?") sound so much more interesting than what they actually come back with (“Malcolm Cowley assures us that it was the flapper stories which made Fitzgerald's reputation as a popular writer”). It takes Eartha forty-five minutes to read this scintillating stuff, and I must pay close attention to distinguish the words from the mumbles, so I miss the detailed reactions of the auditor. I can sum them up, though: beginning with intense interest, next twitchiness, then a suppressed desire to interrupt and correct something (his hand goes partway up), to a wandering of attention. By the time Eartha's paper is done (“… leads us to anticipate the recurrence of these themes in later works”), he has actually, quietly, gently gone to sleep.

Petey Luther's opening observation to Eartha wakes us up:

“You say there are two good stories in the book. I disagree.”

“Hang on,” says Kevin. “Petey disagrees.”

“What is your disagreement?” I ask, straight-man Short, patsy of a bright grad- student’s dreams.

“I don't think there are any good stories in the book. I like it even less than This Side of Paradise. Well, why? First of all, the book is full of race prejudice. I don’t mean just the word nigger—I mean that Fitzgerald was so taken in by the South at this time that he was actually trying to be like a Southerner. Second point: there’s an absolutely inverse relationship between how serious a story tries to be and how successful it is. When he gets serious, he’s embarrassing; or obviously tricky; or sententious. When he’s not serious, he may be slick, but he’s still a snob, and a would-be-Southern one at that. Now…”

“The man was desperately in love, for God’s sake,” Kevin says.

I am shivering.

“May I finish, please, Kevin? Thank you, Kevin. Now it’s true that two of the lighter stories come close to being good stories. And in fact each of them—Bernice Bobs Her Hair and The Ice Palace—has one beautiful line in it. Here's what I think is significant: each one of those lines is spoken by the chief female character, after a scene of catharsis. Right?”

I try to wrench myself out of my invisible trembling fit into the first character which occurs to me, and one I never play successfully, the sarcastic teacher: “And what two lines do you find up to your standards?”

The auditor’s eyes are wild; the bird was shot down but only wounded, and now is crouching, hoping the dogs will pass his hiding place.

Petey Luther is opening his book.

“All right. One: in The Ice Palace. Sally Carrol has been driven back down South by the ice and snow and the ungracious Northerners. And this cracker, or whatever he is, comes driving up to take her swimming, and he asks her: ‘What you doin’?’ And she says: ‘Eatin’ green peach. ‘Spect to die any minute.’ Now that’s a beautiful line, ‘Eatin’ green peach. ’Spect to die any minute.’ All right? Now in Bernice. Marjorie’s tricked her cousin into having all her hair cut off and ruined Bernice’s appearance. So she sneaks in and cuts off Marjorie’s hair—I mean, it’s a real >Rape of the Lock, isn't it?—while Marjorie's sleeping. Bernice is on her way out of town, anyway, and as she passes this boy’s house, she throws Marjorie’s hair up on his porch. Listen to this: '“Huh!” she giggled wildly. “Scalp the selfish thing.”’ That’s a beautiful line. Why? Why is it like the other one? Each of them expresses so perfectly, without Fitzgerald having to explain it, the return of self-assurance a little tease would feel after she's failed to measure up to a situation.”

Miles Hubbert laughs out loud. Miles Hubbert!

“Let me answer him, Mr. Short,” Kevin says, grinning excitedly. “May I?” This is not really politeness, but only a device for assuring himself the floor.

“Go ahead.” I pin my wings on the slippery shoulders of Kevin Candlekirk. The visitor looks at him gratefully.

“I've heard Petey make many absurd statements,” Kevin says. “But this one’s got them all beat. He’s asserting that somehow, out of context, a line—that is a moment—in fiction can be beautiful, more or less by itself. He discounts the author’s preparation for it. as if aptness were a characteristic of the line regardless of its function in the story.”

“You’re willfully misunderstanding…

“May I finish, Petey? Thank you, Petey. I mean, it’s like asking us to believe that ‘Kotin’ green peach. ’Spect to die’ could go into the language, like a great epigram. Fitzgerald never wrote a great epigram in his life. In fact, every time he thinks he’s got one, and he tries to slip in one of those polished, thought-out phrases, he ruins his tone—like look, how could anything but a really sharp story survive an opening line like the one in The Ice Palace?” He flips pages: I want to yell at him that this isn’t necessary, but I can’t. He reads. “‘The sunlight dripped over the house like golden paint over an art jar. and the freckling shadows here and there only intensified the rigor of the bath of light.’ That’s not part of the story, that’s part of the notebook.”

“You’re not disagreeing with me, you're talking about something else.” Petey says.

“But the lines you picked are wonderful because they're wonderful character lines. How could you have a wonderful character line in something that didn’t have a wonderful character, and was therefore a pretty good story?”

“I’ll speak about those stories,” I suddenly hear myself cry out, above the opening cough of what would have been Petey’s answer, and the room goes quiet. I am appalled. What was I going to do? Claim that these stories are great works? I mutter: “After, after Janssy reads her paper on what story, what story? The Offshore Pirate.”

A boy might have a difficult moment trying to follow an outburst like mine—not a girl; a girl’s sympathies are seldom general, and Janssy is quite ready, composed. Nerved up. She improvises a little preamble: “Petey calls Fitzgerald’s flappers teases. I suggest there's no way of knowing whether that’s true or not. We don’t know what the word ‘kiss’ stands for in those stories. Anyway, what I want to show is that his understanding of immature relationships wasn’t one-sided.” She begins to read in a bold, take-charge voice, and the auditor’s eyes are bright with hope: “‘If Fitzgerald exposes the heartlessness of shallow flirtation as practiced by his flappers, he also provides one of the most telling examples in literature of the male counterpart, the snow job. The Offshore Pirate is a story about a snow job so elaborate that even we are disappointed when we find out that the boy, who has been pretending to be a lower-class wild man abducting the rich girl, is nothing but a nice, safe rich boy after all. He was fascinating, sympathetic, worth our attention in the rebel character he assumed to snow the girl; he is unbelievably insipid, a perfect creep in fact, when we find out what he is really like, and no more than the flapper deserves. So well do they deserve each other…”

I could groan aloud. She is after Hubbert, of course, though it's the cow-girl who’s blushing. By God, she really is rather embarrassed, and if only I could explain the situation somehow (“You see, Scott, this girl…”), he might be very interested. (There's no way. The students caught the teacher passing notes?)

“'The girl in the story is not even a true flapper,'”

Janssy reads on. “‘She’s not like Marjorie or Sally Carrol or Bernice, who will at least put a little energy into their flirting. Ardita is passive, selfish

Whispering, now. Betty Cass Collins to Miles Hubbert. Hubbert back to Collins, nodding. Recovered, and with a dazzling smile for me in lieu of any spoken apology, Miss Collins simply stands, gathers her books, and walks easily out of the room and away. Mr. Hubbert? He’s grinning now; I cannot say how comfortably, as Janssy, prim and grim and just a little shaken, reads on.

And, in fact, it is Hubbert’s hand which goes lazily up the moment she is done reading.

Should I ignore him, this first time he has deigned to speak? I look at the auditor, as if for permission, and see that he has understood and is fascinated.

“Yes, Mr. Hubbert?’’

“Well, to borrow Petey’s phrase, surely this is an example of willful misunderstanding,” he says mildly.

“The story is simply pleasant, isn’t it? This is taking a joke seriously. That is, the peg’s round, and I think the hole is pretty square…”

“Hubbert!” I yell, furious. “What the hell makes you think you can speak offensively in my classroom?’’

He looks at me, amazed.

“I'm sorry, sir. What did I say?”

I look at the auditor—he, too, seems amazed. I look at Petey and Kevin and Eartha Hearn; they are all staring. Even Janssy is staring. Is it possible no obscenity was intended? It is too late to consider the possibility that Hubbert's was the first sensible comment in a twisted hour. I force my anger up a notch, spread its compass and rage on. “This has been the most extraordinary, stupid collection of misreadings, misinterpretations, snideness and bad criticism I ever heard,” I shout. “How can you people be in graduate school and not have learned to read? Well? Do you think I'm asking rhetorically? I want answers—I may even want nine answers in writing. Well?”

Kevin's hand goes up. This time it’s neither manners nor strategy, but sheer caution. He will get them out of having to write an extra paper if he can.

“Perhaps these stories mean something different to your generation than they do to ours, Professor Short,” he says, his tone pure placation. He is offering me an out for unwise loss of temper, if I’ll take it. The auditor (oh yes, I can tell) wants very much for me to take it; but I must refuse him now.

“Listen,” I say, feeling triumph; for it is the exposed, the angry, injudicious teacher, railing at his students, who is giving them something of himself. “Listen, you’re talking like a publisher. ‘Generation’ is not a critic's word, it’s a word to sell books, and I hate it. Do you think I’m his age? Where’s your grade-school arithmetic? I was born the year this book was published, and he was twenty-four. My father’s his age, for God's sake.

“Listen, one winter in prep school, in the Thirties, long after his name had gone dim—when I was fourteen, and Sinclair Lewis was about the only writer that I’d ever heard of—I was caught smoking, and given a punishment. The punishment was called Five O’Clock Study. It was for stupid kids who weren’t passing, so they could have more time to get their work prepared. They had to work there, under supervision, in the school library. But I was never behind in any work. I was a disciplinary case. So the man in charge would let me rend.

“When I'd finished all the Lewis, and whatever they had of Logan Pearsall Smith, I found Fitzgerald in the shelves, all green cloth and dusty. Three books were what they had: Tales of the Jazz Age, Flappers and Philosophers and The Great Gatsby. I read Tales first. God, how I remember sitting in that dim room, lost in a big leather chair, prevented from putting on my uniform to play shortstop for the school baseball team, which was my only athletic skill. I’d been looking forward to it all year—the sting of the ball when you go left and get the hard grounder, one hand, and the way your arm snaps when you throw hard. And there I was, off the grass, lost among the stupid and the slow, and I read a story called The Jelly-Bean. I was too frail and snotty a little shortstop to let myself cry, but I sat there staring across the library when I’d finished the story with a stare so sad that the man in charge came in alarm to ask me what was wrong.

“I don’t know if The Jelly-Bean is a good or bad story. I only know that it still moves me to reread it—and it's Southern, Luther. It’s Southern. And I know that if you can’t keep yourself open to being moved that way by literature, then you are doing yourselves an unbearably grave disservice in committing your lives to the study and teaching of it. There’s no critic worth reading or teacher worth hearing who’s not a lover.”

(I falter. There are things Petey loves, like Orwell. I shift my attack to clever Kevin. One does not speak successfully to a class, only to a student in it, letting the others overhear.)

“Let me tell you something foolish: as a boy, there in the prep-school library, I scorned reading Gatsby. The title, it seemed to me, implied that it would be about schoolboys—about a particular one with a grandiloquent nickname, as in the Lawrenceville stories, if you know them. We read that way, don’t we, even titles, self-centering the world upon ourselves?

“So I passed it by and, by the time I knew my error, couldn’t find a copy for seven years. Out of print. Unavailable. Gatsby out of print! It was on a troopship, going to Africa in 1943, that I did read Gatsby—borrowed it from the company clerk, read it once, straight through, missing a meal and a roll call or whatever the hell they called it, wouldn't get up and fall in, with the book unfinished, and told the sergeant who came looking for me to screw himself. Got myself on K.P. that way, and took the book with me, and started through it again in the nauseous galley where we washed trays and cups and slopped out food—and was the only man on K.P. who didn’t get seasick; I was too busy to get seasick. Word by word, I read it, page by page, moved by everything: ‘… boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.' Is that out of the notebook, Kevin? No, boy. That’s out of the tissue of his body.

“I was wounded. I suppose you all know that, and it doesn't matter. I cannot tell you how bitter I was when I learned that the way my leg was shattered, I would never be a whole man physically again; but I can tell you when it started not to matter. That was when a friend brought a copy of Tender Is the Night to me in the hospital in Italy. He was not even a particularly literary friend, but he knew I’d been searching for that volume through the bookstores of Casablanca and Algiers and Palermo and Naples—for over a year, every time I got back to a city. It was an Armed Forces edition, paper, with the cover torn off and Jonesy told me that he’d traded a souvenir Luger for it, though he hadn’t cared for the book himself when he tried to read it. I won’t try to describe how it affected me then, but it was still affecting me two years later, when I married my first wife, taking her for the image of Nicole. I can’t—I can’t get away from that book: my second wife, Mrs. Short, is more of a Rosemary…”

I am starting to maunder. I catch myself up, and finish quickly, not very pointedly:

“Shall we be biographers? There are two things in literary history which have made me swallow tears. Those are the letter Dostoyevsky wrote when he lost his daughter, and the death of Zelda Fitzgerald by fire. That happened late in the Forties, in a Southern asylum. I was working for a newspaper then, hadn’t decided on graduate study, and you’d been dead—excuse me—he’d been dead. Long years. The telegraph editor knew. Brought the copy to my desk…”

No. I am not teaching, nor even railing any longer. I am only pleading, and have said nothing to them after all. But to him, perhaps—I have always wished there was some way I could let him know.

“Dismissed,” I yell at the class. “Dismissed. Get out of here.”

But my fantasy is not always that easy to end. There are various endings, to fit the different moods in which I let it play.

The abrupt one I have quoted is the one which satisfies me best.

In another, I look for him when I am finished speaking, but he has disappeared, evaporated in disappointment before he could hear me out.

Then there is one in which he goes off with Janssy, whom, of course, I love in a way which is remote only because it has to be. Thus, between them, he and she tear me in two.

But in the worst of my endings, he is still there, apparently waiting for me to get my books picked up, when Janssy comes to the desk to get her slip signed. While I am diverted, I can tell only that he has strolled across the room. And when she steps aside, thanking me, I realize that he is walking off, smiling, ignoring all the rest of us, friendly and at ease with Miles Hubbert.

Published in Esquire magazine (LXII, September 1964)).

Illustrations by Jim McMullar.