A Youth in the Abyss

by Laurence Stallings

The fabulous F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. An appreciation and a prediction by an old friend.

There is the tale the Swiss tell of a youth who fell into a crevasse, and of his friends who calculated that his body would be freed from its icy entombment after fifty years of progression towards the foot of the glacier. His friends met on the appointed day, so many gnarled and hoarded gaffers: and the lad of yesteryear was borne forth all golden and smiling, poignant of what had been every man’s possession. It seems now that F. Scott Fitzgerald, all golden and smiling, is coming back to us who survived the icy rigors of the Jazz Ago.

Fitzgerald, it seemed to me, was on the edge of that abyss the first summer I oversaw him in Hollywood, which was in the early thirties, some years before his final tragedy. He was stopping at the Ambassador with his darling wife, Zelda, his mission there an assignment to adapt Red-Headed Woman.

There has been much written about that first Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer effort of his at screen writing; the truth, however, has never been told. The fact is that he wrote well, and cynically, about a role Jean Harlow was to play. But in those days he was not the desperate Fitzgerald of his last days in Hollywood, and he used his talents to laugh at the movie character he was portraying, when it was essential that an audience laugh with Harlow and not of her. Scott’s boss was the late great Irving Thalberg, who knew perfectly well he was dealing with genius. When the job was finished, Thalberg called his production staff together and said (I quote from the accurate memory of one of them) … “We have an unusable work in the Fitzgerald script. I do not think it will serve any purpose to tell him so. It would be like kicking a sick man. I’d rather compliment him on the quality of his work, and let him leave here with his head up.”

But the matter was not to go so smoothly. A director, one of the ubiquitous Balkanites of those days, an unhappy fellow who later shot himself, immediately went to Fitzgerald and told him that his script was worthless. (Later, his work was given to Miss Anita Loos to rewrite: and she soon had the world laughing with Jean Harlow as the redhead all gentlemen preferred.) But that had torn it for Fitzgerald.

“The women here,” he said to me bitterly, “are wonderful. Never's been anything like them. But the men are no good.”

(These same men. some ten years later—the list is long: Jimmy Stewart. Bob Montgomery. Ty Power. Wayne Morris, Bob Taylor. Clark Gable, Frank Capra, John Ford, Frank Lloyd: an endless list would measure their manhood in war records not excelled by any other community of mutual interests.)

“I don’t see how any wife,” Zelda said one night when the Cocoanut Grove was jammed with actresses, “can survive out here.”

The tale has been twice-told now, in fiction and in biography. Neither Scott nor Zelda survived the glacial thirties.

I had come to M-G-M in 1937 to work out a three-year contract, a pleasant home-coming after some vigorous years in the newsreels. The first man I met in the corridor of the writers’ stable was F. Scott Fitzgerald. It would have been no surprise to have met him in the Ritz Bar at Paris, or on that dinky little launch to Capri, or even in the one-armed lunch around the corner from El Morocco on Third Avenue. But this Fitzgerald was no longer the golden boy in homo-spun plus-fours. This Fitzgerald was in a long, box-shouldered overcoat of sepulchral black, with a black fedora atop his head I precisely, as if a hatter had just sot it there. He thrust his hand out stiffly, and spoke with a great seriousness.

“Hello, Laurence. What booby hatch have they let you out of?”

I said I had just finished an unpleasant assignment in Hitler’s Germany. “Yes,” he said, “the world is an enormous booby hatch, and you look like a dangerous patient.” He walked on then, and I stood watching him, thinking of the night I had gone with Miss Laurette Taylor to his house…

… There had been the usual Saturday-night bout in progress at his Great Neck house. Laurette Taylor had never met Fitzgerald; the moment we were across the threshold and Scott saw her, he dropped to his knees, took her hands in his, and began to chant:

“My God, you beautiful egg. You beautiful, beautiful egg.” Then he rose and, still keeping her hands, led her to a divan through a scrawl of people, again dropped to his knees and began to repeat: “You beautiful, beautiful egg.” He was saying, by Dada short-cut, that Laurette Taylor was all fertility and beauty and symmetry.

Afterwards, when we had driven back to the country place where she and her husband, Hartley Manners, were staying, Laurette called that quiet, mannerly playwright out of his Saturday-night poker game. “Oh, Hartley,” she began to cry, “I've just seen the doom of youth. Understand? The doom of youth itself. A walking doom!”

It was an extraordinary thing. If you, like I, think that great women have an intuition inscrutable to lesser mortals, then you will understand how I, standing in the corridor at M-G-M, could still hear Laurette Taylor, herself forever golden, crying out, that long-ago night: “A walking doom!” as Fitzgerald stalked along the windowless aisle, where a hundred writers clacked and rattled their machines with God knows how many pages of script that would never reach the cameras.

Scott Fitzgerald would drop by our shop from time to time. He had a sincere respect for my collaborator, a skilled pro named John Lee Mahin.

“Tell me,” he said to Mahin, “tell me exactly the distinction between a lap dissolve and a fade-out?”

Mahin looked startled, as if the man were pulling his leg. “Why bother about that. Scott?”

“Because,” said the man in the long black coat, “movies are a new art, and I wish to learn the medium.”

We were writing a script for a Gable-Loy comedy, and wore under orders to keep it fast and rowdy, to atone for the lugubriousness of the last Gable-Loy picture, a shackled, muted version of Parnell's Irish tragedy.

“Look, Scott,” Mahin said, “there’s nothing like that to learn. Fade-outs and dissolves—they're devices the director and the cutters use long after the picture is shot: and even then they are made in the lab. They’re the Inst thing a writer like you need bother about.”

The face beneath the black hat was blank. The mouth said stubbornly: “But I wish to know, I wish to be a first-class film writer.”

“My God,” John Mahin cried. “They don't bring you all the way out here for a lot of stupid technicalities. They bring you out here because they want people who still have a feeling for the mystery of life. They want your feelings about people. About the characters in the book they’ve asked you to work on. You've got feelings about postwar people no one else ever had. Just write it down any way you like. Just your feelings. They can find twenty hacks to work out the technicalities.”

“Feelings?” He seemed frightened that anyone should ever want him to show his true feelings again.

“Well,” Mahin said gently, “you know. Just give them a tenth of the feeling you had for the people in The Great Gatsby and they’ll damned well be satisfied.”

“Gatsby?” Had he not come to Hollywood to earn a living as a writer who would not be called upon to show deep emotion about anything? Was this not his chance to write without fire, to recoup his fortunes without trying to recapture the old rhapsodic magic of his youthful genius? Here he stood, weighing the terrible import of Mahin’s advice.

“Sure, Scott,” Mahin was repeating, “no one else can do a thing like that.”

Scott Fitzgerald stood fora moment before he answered. Whatever tumult was in his breast, it was clear no one would ever make him show his depth of emotion about anything again; no, not ever.

“Sure, Gatsby,” he heard Mahin saying again, angrily.

“I am ashamed,” Fitzgerald then answered quietly, “of ever having written The Great Gatsby.” Then he turned and stalked from the room.

Mahin looked at me and spoke softly; “Dear God,” he whispered, “I know now the man is dead!”

Fitzgerald was dead? I thought of how once, listening to Ernest Hemingway discuss the merits of two writers of the twenties, the author of The Sun Also Rises suddenly broke off his homily and said curtly: “Hell, why discuss them? Scott Fitzgerald can do more on a page than any of us can do in a chapter.”

Now there were many rebellious writers afoot in those days: with Hemingway there were such as Sinclair Lewis, William Faulkner, Dorothy Parker… you would find some wonderfully stocked shelves they and their contemporaries had left from the twenties… and here was a man saying he was sorry to have placed three volumes there himself. Perhaps his characters were too much of a period; succeeding generations that had no feeling now for his bootleggers like Gatsby and his boozers like the capricious Amory Blaine in This Side of Paradise. At any rate, this man who wanted so desperately to become a film writer found the films cold to his own work, and he was slaving over something written by a lessor man.

Perhaps he meant to tell Muhin that he was sorry to have written of characters which the films considered old-hat—certainly the powers at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer could have swapped some proper- ties for Gatsby or for Amory Blaine in a quick deal with Paramount, which owned them. However, his Gatsby, the rich bootlegger, could excite no interest in a society that no longer had any pretensions to stratification. A rich bootlegger, a rich politician, a rich gambler—it was the adjective nowadays that counted in opening all doors; the character was nothing. And Amory Blaine, who was de rigueur at Princeton in the days of plus- fours, with his pranks at the junior prom and his amateurish interest in honest football, could find no response in the breast of a generation already beset with the coming war against Hitlerian Fascism.

It was worth-while for Fitzgerald to consider this: that whereas Paramount had reaped a fortune with Hemingway’s heroine of A Farewell to Arms—millions of youths finding Miss Helen Hayes able to embody for them all they felt about the lost generation of their sires—Paramount had let This Side of Paradise, with a screen play by Fitzgerald himself, lay forgotten in its prodigious catalogue. Again. United Artists had taken a flyer at the Dodsworth of Sinclair Lewis, as that mid western troglodyte aired his honest soul to the postwar Paris sunshine, with millions standing in line to watch Walter Huston on the screen. Miss Dorothy Parker's A Star Is Born had been a prodigious hit; and Miss Hayes had scored with Sinclair Lewis in Arrowsmith. And as for Faulkner, who has lately won the Nobel Prize? Well, he always had a standing invitation, with Hollywood's great plush doors opening wide at his knock.

It would be impudence for me to evaluate Fitzgerald's work on the basis of its availability to the movies; but Fitzgerald standing there before Mahin had done so himself, bitterly. He was sorry that his ability, to write (as Hemingway had said) more effectively on a page than his contemporaries in a chapter, had been devoted to characters who were already on their way out of the public mind before the last remainders had left the shelves of the booksellers.

Fitzgerald realized he would have need to invent a world of new characters; his old ones were, for that time, very old stuff indeed; and only clairvoyants might predict when they would come to life again. He would try, of course, painfully, before he died, to find some characters in Hollywood; find a Last Tycoon which found no public in its turn. How desperately he wished to bring his lost people to the screen can be illustrated by an incident of the year before his last journey through that vast Capitol of Sentimentality and Suspense. It came about in this way:

Samuel Marx, story editor for Irving Thalberg, had been rung out of bed at two in the morning by a telephone call from Baltimore. It was Fitzgerald on the line, talking excitedly of a way he had found to adapt Tender Is the Night for the films. He began with a rush of words, describing each incident of his projected screen play. Marx, no less than Mr. Schulberg at a later date, had an abiding respect for Fitzgerald's work; he, too, had read Fitzgerald as a schoolboy, was over grateful to him. But the writer in Baltimore, speaking forcefully, was now asking Marx to give him Irving Thalberg's private telephone number.

It is a tribute to Sam Marx's big heart, if not to his judgment, that he agreed. “I’ll get a pencil,” Fitzgerald said at the other end of the line. After a pause. Fitzgerald came buck, and Marx recited the number. After a few minutes of volleying his ideas three thousand miles across the net of night. Fitzgerald suddenly said: ‘‘I'm sorry, but this isn't a pencil I’m writing with. It’s a cigarette.”

Marx waited again, and then gave the number. The next morning a sleepless Thalberg gave Samuel Marx, story editor, a chewingout he would never forget; for Thalberg. awakened at three o’clock by his bedside phone, thought that Baltimore calling meant a tragic communication about an M-G-M actress, ill at Johns Hopkins hospital there. Instead, here was a writer with a half-hour’s projection of a possible story idea to a producer who was responsible for forty pictures a year… It is a pity that this was in the days before a writer projecting a story could be taped by a recording machine. Certainly. I know of no other instance in his later life when Fitzgerald was glowing with his old lire; and I would like to read it now, even though it was the last way on earth to have sold a story to the harassed Thalberg, himself a genius already on the road to a plot on a cemetery lawn.

Those must have been cruel days for F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. It was no place to lodge a no-longer-useful talent. It was peopled with folk from the world he had once conquered. Watching him come and go, head downcast, a walking penitent in his black habiliments, I used to think how fortunate Arthur Rimbaud had been, when he had thrown all his youthful genius to the winds of France—fortunate that he could leave the scene of his triumph … (I had spent some months, in 1935, in the Moslem town of Harrar, which sprawls a mile high on the green hills of Abyssinia. Rimbaud's house was there: I had even spoken with an old man who had helped him in his last days there, when he became too crippled to work at his trade of ivory hunter and gun runner: when he long since ceased to care that he had burst with brilliance and violence upon the fading decades of the 19th century.)

Fitzgerald, no less than Rimbaud, knew the fires of genius; knew his season in hell, but had no such dangerous and romantic sublimation. Instead, his mornings began with a glass of Seven-Up in the coffee shop of a vast and prying studio, always apart from the contract writers turning up for morning coffee. Once he came and sat by me. ‘‘You like working in the movies?” he asked.

I said there was fun, if you get to work with writers and directors that you liked. And then I asked, “Are they giving you a going over, Scott?”

His hands shook then. A young intern might have said: Now here is a barbituric habitue, or a chronic alcoholic. But there are people in movies who never swallowed a seconal or slurped a fifth of gin who can shake like that when the pressure is on, when the cameras are turning and the jokes are falling flat. “They keep changing my stuff,” he said.

“If you let it get to you, it’ll kill you.” I told him. “This thing is a craft, and not an art. It is a work of many craftsmen. Occasionally, they turn out a work of art here. Scott, but that is purely coincidental.”

He thought about it for a moment and asked, “What would you do then?”

I said that, at M-G-M, if you grew to dislike an assignment, then the studio heads were the last people who wanted to continue you on it.

“But I like the story,” he assured me.

“Then you have got a rough time ahead, Scott,” I told him. “You’ve got to get right down to personalities and fight like a badger.”

For a brief time, he grew animated at the prospect of a fight. He began to speak of the script he was writing. Suddenly it came to me that he was discussing technicalities, the things Mahin had urged him to ignore. He told me of a piece of business he had invented; something about a telephone connection with a boy and his sweetheart who had quarreled. The bit he liked best was a shot of an angel fluttering down from Heaven to make the plug-in at a hotel switchboard.

Time was when Scott Fitzgerald could have brought off that sort of thing in a story with matchless grace; but it was an enchantment that a camera, with its prosaic single eye, could never understand. “You’re under a hell of a handicap here,” I said.

“What's a handicap?” “Webster says that it’s an impost placed upon a superior contender.”

Scott waited a moment before replying, and then quoted:

Ask, ere the youth be rated and chidden,

What did he carry, and how was he ridden?

Maybe they used him too much at the start,

Maybe Fate’s weightcloths were breaking his heart.

He set down the Seven-Up and, black hat squarely on his head, he stalked off to some office where he had been hired to show feeling.

***

In the casting alley, near the talent gate of M-G-M, there is a small cocktail bar, the only one near the studio. It does no land- office business; after a day’s grind, we wish to get home. I saw Fitzgerald there from time to time, rare appearances on a stage which had once reeled with his tread. He was usually with a girl, a minor writer, and would be drinking Seven-Up, pure and undefiled. He seemed astonished that I was drinking an old-fashioned. “You can still drink whiskey?”

“Uh-huh. And it’s label whiskey. I can taste the mash.”

“Now,” said the lady at his elbow, “you’ve interrupted our conversation. Scott was being brilliant.”

“That’s good. What about?”

Scott looked at me with an even gaze. “We were comparing Dickens and Thackeray.” he said, like a professor daring an undergraduate to laugh.

“Okay, let’s compare ’em,” I said, trying to draw Scott’s interest. “Dickens had the key to every house in the street. But Thackeray just had a charge account at the gent’s tailoring establishment on the corner.”

“The lady doesn’t think so,” Scott said, refusing to play. “She doesn't like Dickens. She thinks he’s vulgar.”

Time was when his remarks would have been an overture to a cyclone of wit, with no one, including myself, spared the devastation. Instead, he turned to Mahin and began: “Why aren’t you a member of the Screen Writers' Guild?”

“To hell with it,” Mahin answered.

“Every writer,” Scott told him in a quiet voice, “should be a rebel.”

“That’s right.” Mahin replied. “I'm in rebellion against the Screen Writers’ Guild.”

The author of Gatsby said no more. He sat looking into his Seven-Up glass, as if he knew he would find no message in its acidulous depths. He who had been a prize rebel was now sitting three thousand miles away from anything he ever cared for, trying in all ways to conform. And there was no way of communicating with him. frozen deep there in the glacier of his thoughts.

I would hear of Scott from time to time after he left M-G-M. He shunned, mainly, those he had known in the halcyon days. Mr. Schulberg in his novel has set down passages of real distinction concerning his various junkets with new and younger friends. Then, too, there were stories of his contacts for new jobs after he had left M-G-M—one in particular where he had once called upon, and was interviewed by, Miss Shirley Temple: and where Fitzgerald, under the stress of such a juvenile examination by that prodigious moppet, had quaffed fifteen Cokes.

Lord God. I thought, if that could have happened to him fifteen years before, we should all be saving the first edition of his later recounting of such a passage of arms between these oddly matched champions of two opposing schools of self-expression… Then someone told me that F. Scott Fitzgerald had begun to go. At a ranch party in the San Fernando Valley he had wandered off and when his friends went out to look for him, they found him asleep in a field, embracing a haystack.

Time moved on, and some of us went back to Washington before Pearl Harbor, for the world’s ballast had been thrown overboard and the balloon was soon to go up. While there, word came to us that F. Scott Fitzgerald was dead in Culver City, and the familiar chapter was closed. Symbolists might find something in the manner of his death to harp upon… He had gone to dinner with some people who had been kind to him. but years of doctors and their cures had left him no stomach for food or drink. He had said that all he cared for was a chocolate bar, and he had stood before the mantel eating it. When he had done, he smiled at the mess on his finger tips and put them to his month comically to lick them. He fell dead then, with sweet chocolate on his lips.

It may be that the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, slender and special in their cramped field of social consciousness, will disappear from the popular bookshelf. There were writers who knew, when they were sweating it out, that their reading public was many generations away. Stendhal, who concerned himself with the break-up of French society after the Napoleonic wars, goes on record as saying. “I shall be understood about 1880”; while the ponderous Balzac, no less concerned with the same scene, could find Engels writing in his bread-and-butter letters to Miss Harkness that the works of Honore do Balzac wore far better propaganda for social revolution than Emile Zola’s faithful catalogue of the nineteenth- century slums.

But these men were giants, and F. Scott Fitzgerald was not. He was a golden lad who had very little to say, and, however beautifully he said it, there is the possibility that he left behind him little but the music of the prose. He himself could call Gatsby a poor son-of-a-bitch: never a great one, or an enduring one.

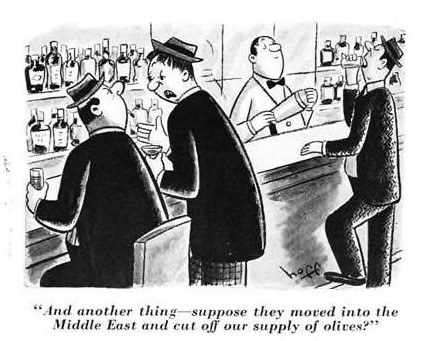

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of a lost generation, he himself was that generation’s first literary casualty. His surviving contemporaries, the Hemingways and Lewises and Faulkners, all most definitely had something to say, though they said it just as sentimentally. Fitzgerald is that man whom grand-sires praise as one of the golden figures of their youth; but their children, listening to Mr. Mizener and Mr. Schulberg, want no part of the real man’s work. It is only those of us gathered at the foot of the glacier who remember the youth in the abyss, recall the short- stories of Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post, the quick, sharp turns of fancy in a world that seemed one hilarious shuttle between the bedroom and the barroom…

It is indeed hard for the oldsters to accept the contemporary verdict that Fitzgerald will be read only by novelists in search of characters, or by biographers with their practiced Freudian wiles. No one since F. Scott Fitzgerald has written so joyously, so economically, of America’s last fling at adolescence, in the days when Germany had been rendered hors de combat, Moscow had turned humanitarian, and the people of America had nothing to worry about.

I like to think that, when the generation is finally summed up, Amory Blaine will be elbowing Hemingway’s aficionados in the Ritz Bar at Paris, in a paradise regained: while Miss Dorothy Parker’s Big Blonde will be weeping into booze brought to her shabby room by one of Faulkner’s Negro emigres, part of a vast rum empire whose profits enabled the flamboyant Gatsby to beat Mr. Dodsworth to the check at Fouquet’s. Thai’s what I want to think—and to hell with those who think contemporary fiction, the present postwar crop, can stand on the same shelf with that of the other lust generation. I'll wait for the youth who fell into the crevasse.

When he fell, there were silly cacklings about distraught youths like Thomas Chatterton; but I think more of a provincial Catullus coming down to Romo from the lake country to heckle Caesar himself, and leave his lampoons and his lyrics on the barbershop walls, a golden youth going to hell just a little bit faster and more brilliantly than those who traveled with him, bound for the same shade… But now the glacier has given him up again, all golden and smiling: and if you of the new generations wish to know what that time was like, you have only to read the accounts of Gatsby and his like.

Published in Esquire magazine (October 1951).

Illustrations by some Esquire artists.