Beautiful Fools

by R. Clifton Spargo

11

MOST LIKELY HE EXPERIENCED THE ABSENCE AS LONGER THAN IT was, so he approached the clerk at the front desk, resolving not to let his worry show.

“Buenas tardes, Senor Fitzgerald,” the clerk greeted him.

“My wife hasn’t left word for me?”

“No, senor, you are expecting a message?”

“You haven’t seen her?”

“?Hay algun problema? Something is wrong?”

“No, no,” Scott said. “We must have got our wires crossed in town. I was supposed to meet her, I forget where.”

“Mrs. Fitzgerald has not been here,” the clerk said as he checked the empty mail slot.

On the cinder path that threaded among the bowing palms to the villa with its red-tiled roof, Scott replayed the past three days in his head, the mistakes, the opportunities for reprieve. He shouldn’t have taken her to that bar Saturday night in Havana; he should have reacted more quickly when she was in danger. He should never have allowed Mateo to take charge of their safety. Also, he had been far too lax about the wine and cigarettes, neither of which Zelda was permitted at the Highland, neither of which he was to allow her while on holiday—but once they were out of town he could never enforce the rules set by her doctors. Normally, when she started breaking down, there were warning signs. He had time to catch on and reprimand her, speaking to her at times as to a child. Saying simply: “That’s enough.” Now and then seizing her (a full-on clash of wills might ensue, objects thrown, slaps exchanged) to lead her home. His gruff tactics drew the attention of their friends, especially in the years before most people had intuited the depths of her illness. Many of their acquaintances accused him of being boorish—you couldn’t treat a grown woman that way—but Scott knew from experience that often nothing else worked. Outside the church this afternoon, after he had caught up with her to find her raving about providence, about the words of that damned yellow-eyed clairvoyant, he’d known what to do. But he couldn’t bring himself to humiliate Zelda in front of new friends.

He climbed the courtyard stairs, pausing at the door to his room to catch his breath, the tightness in his chest like pangs of regret, the by-product of the afternoon’s rush of activity. His brow soaked, he raised the handkerchief to it, blotting the sweat, remembering only afterward about the coughed-up blood. Lowering the handkerchief, he eyed the reddish smears on the linen, the orange-yellow halos that had formed above them. Inserting the key in the lock, he called her name in a circumspect whisper—“Zelda, Zelda, are you home?”—then cracked the door.

Quickly he cased the room, checking the bathroom, finding his watch on a shelf by the sink and sliding it onto his wrist without looking at the time. On the balcony he surveyed the grounds of the hotel. Beyond the line of scattered, seething palms, the surf pounded the sands, hungrily lapping up beach. She was a strong swimmer, but the white-capped waves were as high as he’d seen them—the Gulf current must be formidable by now.

Clearly, she hadn’t been back to the room. He checked the sun on the horizon: maybe an hour and a half of daylight left. He felt the chill of encroaching rains, the moisture in his lungs. Where could she be? Only so many places to visit on this peninsula, only so many ways to get lost, even if you wandered straight into the wilds of its largely unsettled terrain. The forests weren’t all that deep. He knew of marshes, some swamps, maybe also quicksand; he had heard tell of alligators, iguanas, and boa constrictors. Of more immediate concern, though, was the human element. It was a peninsula of impoverished fishermen and their families, only recently annexed as a leisure destination by rich Habaneros, by Americans and Europeans. He remembered the unsavory characters from this afternoon’s bodega, the rules about where women were allowed, where they weren’t. He could imagine how deep the locals’ resentments of tourists must run, and Cuba wasn’t the south of France. This was an island nation of gambling, speculation, and organized crime, a one-crop economy propped up by dictatorships and frequent coups, a country kept under thumb first by Spanish rule, now by American moneys and policies.

Pulling the French doors shut behind him, Scott shuffled past the bed to his suitcase set on the steel rack, rummaging through the clothing until he found the pair of BVDs in which he’d wrapped his handgun back in Encino. Too bad he hadn’t thought to bring it with him Saturday night at the bar. He checked the cylinder to see that the gun was loaded and cocked the hammer, holding the Smith & Wesson aimed at the ground, peering down its barrel. Then he released the hammer with his thumb and eased the trigger out. In case I need it later, he told himself, wedging the gun into his belt under his jacket.

On the beach he listened to the rhythmic wash of waves, the predictable break and roll. He had lived regularly with the prospect of her death for a decade now. Only let her not suffer, he said to himself. Here he was, a man who hadn’t prayed for anything in years, rubbing a medallion between his fingertips, imploring a saint to whom he’d never given a moment’s thought for help as he headed down shore toward the main island.

“Saint Lazarus,” he whispered, “she needs looking after more than I do.”

Into the sky’s extravagance of color he strode, the luminous glow of orange, red, and fuchsia reflected on the sea’s surface like parade banners, his eyes welling from the brilliant sun. Whenever he imagined her gone from the world, everything else melted away. What did squabbles and recriminations, rivalries and sexual infidelities matter? How could drunken brawls and shouting matches hold any importance in the face of disaster? She was his true passion, the one thing he could never get over. He thought of diving into the waves even now, hazarding all to save her, letting the water creep into his leaky lungs, but if she had in fact gone under, he didn’t know where. He accused himself of not checking the boulders before she plunged from the crag earlier in the day. She must have registered his neglect, must have told herself, He cares more about preserving his precious lungs than about my splitting my head open on some rock.

“It’s my fault,” he said aloud. He was incurably selfish, even narcissistic. Maybe that was true of all artists. He drank too much and neglected her. She distracted him while he was working, sometimes only by sitting still and saying nothing at all, the mere possibility of disruption making him tense and irritable. He ordered her to leave hotel rooms in which they stayed so he could write for a few hours. Even in strange cities, even in cold weather. On countless occasions he sent her away, and once she had asked, in a broken, sincere whisper, “But where should I go? I don’t have anything to do with myself,” and yet he still shouted, “Why is that always my problem? Anywhere but here, please. Can’t you ever leave me alone for a few hours?” As soon as she was gone, though, he gave in to regret, spent the entire day worrying about her instead of working, fretting about what might happen to her alone on the streets of Paris, Baltimore, or New York. “Your problem,” she once said, “is that you can’t work when I’m in the room, sometimes even in the house, but you also can’t stand it when I’m out on the town without you.”

He could hear her voice, the familiar tones, that bizarre sense of humor about his neurotic need to put her out of mind. “Did you enjoy bumping me off?” she asked him once while she was marooned in Prangins, shoulders, breasts, and face plagued by rashes, her entire being afflicted by the itching and flaking of a psychosomatic disease that got worse with every hour spent in his company, until the doctors pronounced him a precipitating condition and banished him from the hospital. And what had he done in the face of her seemingly incurable distress? He’d written a story hypothetically killing off the cracked soul of his poor wife, easily one of the four or five best of his career.

“What was it like with me gone, once and for all?” she said after reading the story.

“Don’t be silly. I wrote from my deepest fears, I exaggerated my wrongs and put them on trial, punishing the man for what he hadn’t even meant to do in the first place.”

“It’s a beautiful story, Scott, one of your very best in my estimation,” she said. “You can tell he loves her, especially now that she’s dead. But you and I have read enough Freud to know that our deepest wishes and deepest fears are closely related. By the way, I liked the detail of his locking her out of the house; I imagine that part wasn’t hard to come up with.”

“He didn’t do it on purpose.”

“No, he was drunk and could hardly remember anything at all,” she said, smiling royally, luxuriating in her ability to forgive his flaws. “I’m told it’s a common phenomenon with dipsomaniacs. Vague remorse wrapped up with innocence, outrage at the very deeds perpetrated by their secret souls.” She had let the point sink in before kissing him on the cheek. “All the same, the story made me feel loved. I felt sorry for you without me. You got one thing right. When he imagines she wouldn’t want him to be so alone—that’s true, Scott; if I disappear on you for good, if ever I can’t climb out of this hole in myself, I won’t want you to be alone.” She was capable of a thousand small kindnesses. He resented the doctors who diagnosed her as having a megalomaniacal personality. Though vicious and spiteful when wounded, she was kinder, more giving and bountiful, than anyone he’d ever known.

The beach narrowed at the far end, the sun slipping low in the sky, soon to sink into the waves, the air above it purplish and peach with a low plane of clouds running out from the fiery center in striated lines. He had walked a mile, maybe farther, so caught up by his obsession with finding Zelda that he only now detected the drop in temperature.

He remembered the letter, wondering if it might provide a clue to where she had gone. Pulling the perfumed green stationery from his journal—that sudden trace of her in the air sent a coarse sadness through him—he began to skim it: “Dearest Scott, I want you to know how much it means to hear you promise to take better care of yourself.” He looked for phrases: “Hearing you speak with hope” and “fills me with a belief in the future.” He skipped ahead: “This may be hard for you to understand, as I myself am only now beginning to understand it.” Then further on: “If you lose your moorings, I will too.” The letter was full of judgments about his fine character, how he might get it back. She spoke of his writing, his struggles to write, comparing him to his peers. “You are a finer writer than any of them, in every way, and oh so much more my own favorite writer.” She begged him to think of what they’d built together, not only of what they’d foolishly torn down. “You’ve been sad for such a long time.” Then she brought it back to herself: “It makes it hard for me to go on when you speak of your life ‘being over.’” He skimmed the rest, nothing new here, nothing especially ominous. Except perhaps all that overbearing hope.

A warm slosh of water filled his shoes. Without realizing it, he had wandered to the ocean’s edge straight into a wave rushing high onto the sands. The water squished unpleasantly in his socks, trapped in the arches of his shoes. He inspected the beach, unable to proceed much farther. Immediately ahead the tide swallowed the shore as whitecaps rolled over a small embankment of sand, on the other side of which grass and reeds and trees grew out into the salt marsh. The sulfurous stench of landlocked tidal currents greeted him and he could detect the percussive chatter of insects, here and there the flapping of a crane or a pelican as it skimmed low over the grasses. Sitting down to rest his lungs, he heard the cawing of a gull and watched as it plunged into the marsh and emerged seconds later from behind the tall grass, a fish held like a thick branch in its bill as it flew directly above him. Several other gulls cawed searchingly after it, gliding on the wind, wings spread like children’s kites as they swooped slantingly, clamoring, until the first bird dropped its prey on the sand not far from him. The fish convulsed, flipping into the air, as four additional gulls congregated (when one flew off, another descended to replace it), all stabbing mercilessly at the dying fish with hooklike beaks.

He felt the odd desire to lie down. The terraced sands carved by the day’s waves, caked by sun but soon to be swallowed by nighttime tides, looked inviting. But he couldn’t rest as long as she was gone. Not a person in sight for as far as he could see—why not call out? Go ahead, he urged himself. Zelda, Zelda, he recited her name but couldn’t bring himself to utter it aloud. If he spoke her name on this desolate beach where no one could hear his cries, if he listened to his fears in a call and response between himself and the sky—well, who knew what possibilities that might invite? He couldn’t predict how he’d }respond to hearing his own desperate need for her to be safe echoed back to him.

It was time to ask for help.

***

The manager hesitated at first, doubtless recognizing Scott as the man he’d evicted from one of the cottages only last night. Scott explained that his wife spoke almost no Spanish, and that she suffered from mental illness, a patient in an asylum back in the United States. This news put the manager on alert, instilled in him a proper sense of urgency, though Scott resented having to leverage Zelda’s illness to get him to do what he ought to have done simply and automatically. “I am a somewhat famous writer,” he told the manager, wishing to see him squirm. “If my wife dies in an accident on your beach, it will be bad for the hotel’s reputation.” Of course, if Zelda learned about it later, what he’d said to provoke this man into action, how many people knew about her condition as a result, an entire hotel staff put on alert for a madwoman gone missing, she would be mortified. But she had left him no choice.

Maryvonne hastened from the restaurant as soon as she saw him, wending her way through small clusters of guests assembled on the patio to watch the sunset. “Have you found her?” she inquired, as though she’d thought of nothing else for the past two hours, and perhaps that was true. “How can I help?”

There was nothing this woman could do for his wife, least of all if Zelda had already inflicted some awful, final fate on herself. Most often her suicide attempts were bits of theater executed in his presence: the time she jerked at the steering wheel attempting to plunge them off a cliff on the Riviera, or those occasional dashes for tracks when she spied a passing locomotive. He was always there to save her from herself. This time, though, she was roaming tropical terrain in a foreign land in the midst of a mild break, perhaps unable to find her way back or to ask directions to the hotel. Harm might descend from anywhere, from almost anyone.

“You have heard from her by now?” the Frenchwoman asked, as he escorted her to the perimeter of the patio, away from the other guests.

“She left a note,” he told her. “She’s off on yet another walk, it appears.” Though he had just asked the hotel manager to dispatch several employees to comb the beach and make inquiries in the village after his wife, he nevertheless refused Maryvonne’s kindnesses, maybe on instinct, maybe on the sad speculation that he didn’t want her around if it all went south. It would be one thing if they found Zelda wandering the village, or swimming in strong waves, alive and well, waiting to be recovered, then escorted to the hotel so that everyone might pretend nothing had happened. Quite another if he got word from the hotel staff that local police had discovered a drowned woman.

“She will be fine, then?” Maryvonne asked, unconvinced.

He could tell from the tilt of her head and the tone of her voice that she didn’t believe his feeble lies. Why should she? She was asking to be let inside his sorrow and he was saying no.

“Perhaps I will look for you later,” he said. “Perhaps Zelda and I together will look for you later, if she’s up to it.”

“Would that not be lovely?”

“Will you be at the bar, here on the hotel patio, on the porch of your cottage?”

“One place or another,” she said before retreating to the hotel restaurant where Aurelio sat waiting for her, waving once at Scott without rising.

He discovered Famosa Garcia at a corner table in the hotel bar, reading a newspaper. The old Cuban looked up at Scott as if the two men had a scheduled appointment.

“Ah, Senor Fitzgerald, I am pleased to meet you.”

Scott was anything but pleased. He didn’t care to listen to news of any sort from Mateo’s messenger, even if it meant the entire police force of Havana was about to descend on him without warning. Mateo was just using the threat of legal hassle to keep tabs on him. Scott wanted to have it out with Famosa Garcia, tell him how lousy his timing was. For a split second, though, he paused, wondering how far Mateo’s network reached, whether he was aware of today’s events on Varadero, whether his skilled messenger might already know of Zelda’s disappearance—a wild thought, so Scott put it out of mind.

“Have you nothing to say to Senor Cardona?” Famosa Garcia asked.

“Can you get a message to him?”

“Anything you like; I am only enviado, maybe you say, the reporter of news?”

“Envoy.”

“An envoy, yes, at your service. So we drink first?”

The combination of the man’s velvety voice and the milky eye that couldn’t focus was appalling.

“I’ll hold off on the drink,” Scott said as the waiter approached. “Una cerveza, that’s all for me, gracias.”

His head was spinning and he knew himself to be treading dangerous ground. Did he have the guts to say what he was about to say? The more he thought about it, the more he believed Mateo’s kindness to be one long bluff, maybe not from the start—but somewhere early on during that long Saturday night, Scott had become a mark.

“Tell him I’m broke, won’t you,” Scott said, playing his hand more decorously than he intended. “I’m in no position to invest with him, wish I could, that I had some value, some net worth.”

Famosa Garcia ran his fingers through his mane of hair, his chin bent piously over his drink as though he had no stake in what was being said.

“I’m grateful for what he did for me back in Havana,” Scott continued, feeling the old man’s silence as leading, as though he was being given just enough rope. “Maybe he wants to broker an investment for me for the sake of fond memories we share of New York, and I appreciate all of this, I do, I enjoyed our two nights in Havana, I’m grateful for his company and his assistance—”

“He does not require your gratitude,” Famosa Garcia said. He was here to talk about the incident from the other night, the progress of the police investigation.

Scott couldn’t believe what he was hearing. What more was there to say about the death of a peon in a juke joint, a death in which neither he nor Zelda had played any part?

“My employer, he finds another witness, this is no problem. Senor Cardona always he have many ways of solving problemas.”

Obviously, the witness in question was someone Mateo had coerced. None of it made any sense. Why did they need a false witness in the first place? But the customs of Cuban law were beyond Scott’s grasp. He longed to protest, longed to shut down the conversation and shout, “Well, she’s gone, the invaluable witness is gone, there’s no need for machinations, let justice run its course.”

“What is it?” Famosa Garcia asked him. “You have something to say.”

“What does that get us?” Scott finally asked.

“Excuse me,” Famosa Garcia said, as though Scott had directly challenged him.

“The trumped-up witness, how does that protect my wife?”

“The witness is the woman who the men fought over, she will say so.”

“Well, convey my message, please,” Scott said, “my sincere gratitude for his help. I wish I had some way to repay him just now, but I don’t.”

“It is done,” Famosa Garcia said, pushing his chair back from the table. “I am only envoy.”

Scott felt that etiquette required some gesture of appreciation for the man’s efforts.

“My wife kept the picture we took together,” he said. “She was quite pleased with it.”

“And how is Senora Fitzgerald?” Famosa Garcia asked, his one good eye peering at Scott. Was it possible, he wondered again, that this man was behind Zelda’s disappearance, all of today’s events somehow orchestrated at Mateo’s command?

“You know where she is, don’t you?” Scott asked spontaneously, but it was just the long day of drink talking, maybe also the heat.

Famosa Garcia stared at him without flinching, neither dumbfounded nor outraged. Either he knew nothing or he was a masterful actor. “She is in her room, tired from a day spent in the sun, no?”

“Sure, that’s all I meant. She’ll be sorry to have missed you,” Scott said. “We were grateful for your guidance in Havana, and we also found a church here on the peninsula.”

Of course, Scott said to himself, I should have thought of it sooner. He shook the hand of the Cuban, wishing him safe travels, even as he pictured Zelda in the pews of that small mission-style church, crouched beneath its exposed-timber ceiling and the modest holy glass windows while light drained from the sky.

That’s where she had gone, the village church; he felt it with dread certainty. But would she still be there at this hour? He took a long, slow breath, ignoring the rasp in his chest, gathering himself, sipping at his beer slowly to slow his pulse. He was balancing two competing emotions: sudden relief from the insight into his wife’s mind, this hope that the day might yet resolve itself peaceably, mixed with an undercurrent of terror. You haven’t found her yet, he reminded himself. He needed to set out for the village right away, before night descended, except—the thought held him back, if only briefly—he was afraid of what he might find.

He pulled out his Moleskine, scanning its pages, pausing over a passage about Sheilah written days ago, in a stupor induced by alcohol or remorse, during that long night on which he’d vowed to go on the wagon, fighting off those middle-of-the-night dregs, then fighting with his mistress before fleeing to Asheville the same morning. “It was altogether possible that Colman had pursued her so diligently, had stayed so long with her, for no better reason than this: she was someone who could keep a secret.” Lost in his own words, he gave in to regret over the way he’d parted with Sheilah, who had put up with so much from him these past two years. What if he never saw her again? “He hadn’t gone looking for that quality in her. It showed in her bearing, a sense of style mixed with decorum. She was among those whose ranks were thinning from generation to generation, a woman designed for privacy, that rarest of products in a herd-like society, the truly trustworthy person. If as a rule natural-born confidants didn’t pursue work as gossip columnists, Colman had to admit it was perfect cover. In her bed he could unburden himself; there and there alone he was able to speak of matters which had plagued him for years, the secrets he knew about his wife—how damaged she was even in her finest moments, even at the peak of recovery—but could never reveal to the wide world.”

His instinct was to call Sheilah—why not?—she would want to know he was alive. She would apprehend the latest tumult into catastrophe without explanation. He trusted her discretion and judgment in all matters, so maybe she could tell him what to do next. He marched to the front desk and informed the clerk he needed to place a call, and for a minute, as he hovered over the piece of paper handed to him by the clerk, he was unable to remember the number, but then it came to him. The clerk indicated a phone by a dark wood bench where he could take the call once it had been placed. Thumbing through the Moleskine, he rehearsed what he would say to Sheilah. “Never let it be said there’s no way down from disaster,” he said and scribbled it in the notebook. He remembered the trip to Manhattan this past fall, the vows he had made to Sheilah afterward to divorce Zelda once and for all. It was selfish of him to want Sheilah’s advice. He was too dependent on her sympathy.

The clerk caught his attention and shook his head to indicate that no one had picked up, and Scott nodded his appreciation, relieved that the decision had been made for him. He had no right to confide in her ever again. And yet there was no one else, other than perhaps Zelda herself in her periods of lucidity, who could begin to intuit how devastating the events of today might prove. “Zelda was gone, Zelda was dead.” He experimented with the words, silently, chanting them so as to postpone their meaning.

***

He asked for escort into the village, but when told how long he would have to wait insisted on making the journey alone on foot, a plan frowned on by the night manager. This wasn’t Havana, where all along the Prado the clubs and bars thickened until the morning hours with revelers, tourists, and, yes, thieves too, but also soldiers and policemen. The roads on the peninsula were treacherous at night, often washing out when the rains came. The night manager walked Scott onto the patio, made him listen for the low rumble of thunder rolling in from the Caribbean Sea below them. “You know about the alligators?” the manager asked, even as Scott felt inside his belt for his gun, answering cocksuredly, “Thank you, but I’ll be fine.” The manager handed his guest a lantern. “You will require this to find your way.”

So, holding the lantern before him (rather like a figure he’d once seen depicted on a tarot card), Scott set out, tracking the dirt trail from the resort through the hum of the noisome roadside marsh, swatting at the insects perching on his neck, heeding the flop and fall of large fish or reptiles in the mucky waters behind the reeds on either side of the dirt lane, several of the splashes long and full enough to accommodate a gator. In the thin darkness, as he circumvented a bank of dunes covered in grass and sand brush that ran off into forest, he passed couples from the hotel returning from evening strolls. He hurried along a narrow partially paved road, past shacks where locals lingered on porches and children at play in the yards crawled out from behind trees like nosy nocturnal creatures. Now and then he stopped to ask someone in crude Spanish, “?Donde la iglesia?” and a native would skim his face for information before gesturing down the road, assuring him that it angled straight to the center of the village—no way to depart from it, no way to miss the church.

Soon the cottages and shacks fell away, and with them the people, as the air grew dark and heavy with moisture. He listened for the rumble of encroaching storms, but all he could hear was the drone of insects, the gurgling croak of frogs and lizards. He checked the kerosene in the lantern.

Dead on his feet by the time he reached the village, he welcomed the sight of the church set back from the road in an open field palely illuminated by the nighttime sky. As clouds rolled in shadows across the ground, they darkened patches of long grass, scrub, and thicket, and Scott muttered aloud, “What has become of her?” He walked under the freestanding arched gateway to jostle the front doors, locked, then walked round the side toward the square tower addition at the rear, attempting the door by which they’d entered the church this morning, rapping on the thick wood. Anyone inside, the priest or perhaps Zelda herself, would be certain to hear him. It made perfect sense. She had fled to this place to lock herself away from that which was chasing her, to take refuge from the bad tidings of the spirit world; but whatever had transpired in the hours since, she was no longer in the vicinity. No sound issued from inside the church. If the priest heard the knocking, he chose not to come forward into the night.

The modest chapter house connected to the church remained dark. Was there any point in knocking there too? What if the priest answered only to say, yes, he’d let Zelda inside the church to light a few candles but sent her away hours ago? Nevertheless, Scott approached the door, all other avenues exhausted. He rapped firmly if reluctantly: no answer.

So he retraced his steps through the thickened night, listening to peals of distant thunder, detecting the scent of this warm, muggy place for which he felt a strange affinity, not unlike what he felt for the Deep South. He was one of those who believed that the American South held the key to the nation’s soul. For a long time he had intended to write the great novel of the Civil War, having often interrogated Zelda about the moods and texture of the land as it had inscribed itself on her being. Only months ago, while working on Gone with the Wind, he had pored through his ledger and her letters in search of sketches from Zelda’s childhood, of anecdotes accumulated while stationed in Montgomery or while visiting her family, of lore gathered while living in recent years in towns such as Tryon and Asheville. Early in their marriage she used to stop him in the middle of a conversation to ask, “Are you writing that down?” or “Are you memorizing my words again?” She could think of nothing more amusing—that was how she put it—than to be someone’s muse. He pretended, through his father’s ancestry, that he too had the South in his soul, but he didn’t, not really. Which was why he relished his wife’s stories of her beloved yet horribly constrictive South, the stench of wisteria in springtime and the ache of the rain-drenched landscape, the history that came at you from all sides, filling up your imagination before you had time to exercise it on your own. As he walked through the thinly forested marshlands of Varadero, he felt he was tracking the scent of her childhood.

At the hotel he checked with the manager—still no news—returning the lantern, then escaping by a side entrance to follow the dunes out beyond the stone cabins to the shoreline, there to watch the roll of whitecaps as he roved moonlit sands for a long while, not really believing he would come across his wife.

***

“Everything is okay, I understand,” Aurelio hailed him as he approached, and Scott smiled, saying, of course, why wouldn’t it be?

Maryvonne and Aurelio had been drinking all night in the company of an American couple, an older man and a young bride whose names Scott didn’t catch. Maryvonne presented Scott as a dear friend, only gently referring to his wife after he hinted that Zelda had elected to remain in her room. His European friends were nothing if not discreet, the sole allusion to today’s outing to Hicacos Point occurring when Maryvonne reached under the table to capture and squeeze his hand in her fine, slender fingers.

It was probably well past midnight. Scott, in a black cast iron chair set before a black cast iron table, traded small talk and refused to glance at the watch on his wrist. Now and then he plundered a thinly picked over plate of cheese and fruit brought to the table before his arrival. He was ravenous but loath to admit it. His wife was dead for all he knew, and here he was craving food, the first time in weeks he’d had any appetite whatsoever.

“Do you mind?” he asked Maryvonne, helping himself to another chunk of the cheese.

“Scott, when was the last time you ate?”

He thought about it for a minute; the answer, of course, at the picnic this afternoon, and hardly anything then.

“No wonder you are hungry,” she said.

Dying for a drink, he offered to buy a round.

“We have to be going,” said the American man, who had tired eyes and a sallow jaw. He must have been in his early sixties, the wife still in the bloom of youth. She seemed reluctant to leave.

“Oh, don’t spoil her fun,” Scott said, but the man didn’t appreciate misplaced gallantry.

Scott feared Aurelio and Maryvonne would follow the couple’s lead and turn in. Over a long career as an owl and a drinker, he’d learned that even a single person’s decision to call it a night could trigger a chain reaction, bringing the most vibrant of parties to an end. Among apes, someone once told him, most likely it was Ernest, yawning wasn’t just contagious, it was communicative. When the head ape yawned, it was a cue—we’re going to sleep, folks, whether you like it or not; and the other apes returned the yawn, submissively, suddenly tired themselves. From a young age Scott had quarreled with those inclined to quit on a good time before it was exhausted. He would sooner fall asleep on his feet (had done so on many an occasion) than leave a party early. Tonight, though, wasn’t about extending pleasure. It was about postponing solitude for as long as possible.

The waiter returned with Cuba libres, and Maryvonne and Aurelio showed no signs of quitting on him.

“I never finished the story of my injury, about which you asked me earlier,” Aurelio said. A crack of thunder hammered the sky, followed by lightning that illuminated the sand dunes and grove of pines behind them. The flames on the lanterns surrounding the patio bent low, nearly extinguished by a heavy wind, as the nearby palms and almond trees chattered nervously.

“What is this storm waiting for?” Maryvonne remarked.

“Sshh,” Scott said, playfully putting a finger to her wine-stained lips. “If you don’t acknowledge them, sometimes they pass right on by, like noisy drunks at a party.”

“It was more difficult to accept I had the injury than anything,” Aurelio said. “It is only until you are better, they say to me, confining me to a cot, only I was not prepared to fight again and try to have a good result. In the hospital I do not get better, do not get stronger.” He could remember the morning when the staff came to impart the news that he would be sent away, the nurses checking on him more often than usual, promising the doctor would soon speak with him. In telling his tale Aurelio lingered over phrases, trying to find the right words in English, Maryvonne whispering to him in French or Spanish, helping him recall his own story, their voices tapering off in the wind, as palm fronds whispered above them.

Off to the north waves clapped heavily on the beach, sometimes supplemented by a long sigh of surf, the ruminations of the storm hanging on the wind. Scott let the Spaniard’s voice wash over him, oddly comforted by this tale of woe that had nothing to do with his wife’s sad story. He didn’t have to pay close attention to the minor details because there was nothing at stake for him in them.

“Did we mention this part of our story last night at the cottage?” Maryvonne asked, worried lest her cousin prove tedious.

“I don’t think so,” Scott said. “Besides, Aurelio and I share an interest in the niceties and minutiae of warfare.”

He imagined that the hotel bar would be closing before long and wondered if there was time for another round.

“You never want them to smile at you,” Aurelio said, “with that face they put on for the dying, the maimed, the castrated.” The sadness in his voice was curtailed only by the knowledge that his bright nurse of a cousin would soon rush to his side to see him through the valley of death. He could speak objectively of his own pain as a consequence of her intervention. He could report on what it was like to be a wounded, dying soldier stalked by a sedately smiling doctor, soon thereafter to be marooned in a refugee camp; and he could do so because, for all practical purposes, he spoke of another man’s fate.

“I wish Miss Zelda were here to share this story too,” Aurelio said, and the fact that the Spaniard was so ready to believe Zelda safe in her room made Scott think less of him. How could such a man have survived a war? But the Spaniard’s affections were so simple and sincere that it was difficult to stay angry with him. “Please tell her I say that we miss her.”

“Well, on that note,” Scott said, “I must attend to her.”

“And we attend las peleas de gallos tomorrow evening?”

“Of course,” Scott replied, then turning to Maryvonne. “Will you be joining us?”

“Is not allowed,” Aurelio said stiffly, and Maryvonne rose, her reddening face averted from her husband. In the French manner she pecked at each of Scott’s cheeks, her lips moist on the corner of his mouth even as water simultaneously struck his forehead. The rains had come at last.

“Perhaps Zelda and I will discover,” she said, pausing on that word she pronounced de-coovere, then continuing as if for effect, “activities still more exciting.”

“If she’s up to it,” Scott said, reminding himself that everything uttered over the past hour was more or less a lie. None of these plans—the cockfights, the renewal of friendship, the dinners—would come to pass.

Winding through the wildly tossing palms en route to the villa, he dawdled long enough to be sure the Europeans were out of sight, then doubled back to the reception area to find the night manager yawning, bracing his forearm against the counter.

“What are we to do next?” the manager asked. His narrow, rodentlike face was fearful, not a good sign.

“You’ve been in touch with the police already?” Scott asked, though he doubted the man had taken any initiative.

“I am waiting only for you, that is all,” the night manager said. “We will call first thing this morning?”

“What,” Scott cried, experiencing outrage even as he performed it, only too happy to pawn off his own negligence on this obsequious, reproachful, slippery man. “But hadn’t we agreed—if the search parties came up empty, you would call the police right away?”

“Senor Fitzgerald, I apologize, I do not understand, I thought you want me to wait.”

“For what?”

The night manager shrugged his shoulders.

“Tell me what we could possibly be waiting on, for God to step in and find her himself?”

Scott wheeled about, started to walk away, head spinning with recriminations, for himself, for the night manager, for that damned clairvoyant and her cursed words.

“I should call the police?” the night manager called after him.

“Of course,” Scott said, halting in his tracks, practically spitting the words.

“In the morning?”

“No, goddamnit, as soon as possible.”

“They will ask to speak with you.”

“So send them to my room. If I’m not there I’ll be on the beach—”

“But the rains,” the manager said with genuine concern, and the two men peered through the French doors that opened onto the patio, where nighttime staff were pulling down lanterns, stacking chairs, and securing tables with rope so they wouldn’t get blown off in the fierce winds.

“At any rate, I’ll be easy to find,” Scott said, returning to the desk to make it up with the man. “Tell me what you think I should do next, Senor, but I’m sorry I’ve forgotten your name?”

“Senor Valdes,” the night manager replied, then added gently, “You must sleep.”

“I’ll try, but you tell the police they needn’t worry about waking me.”

“I will call them, Senor Fitzgerald, they will find her, who knows, maybe the priest from the church, Padre Hijuelos, he find her a bed for the night—but la policia will know, they will know soon enough.”

He had put off returning to his desolate hotel room, but he couldn’t postpone it any longer. So he headed through the French doors into the lashing rains, the night manager whose name he’d already forgotten shouting after him, maybe starting forth with an umbrella, but not before Scott, assisted by the wind, slammed the door shut; and again he was on the cinder path, now pooling with water, having to hop from one patch of higher ground to another, weaving among the sudden ponds already inches deep. There was no way to continue the search in this storm. It was impossible to see even a few feet ahead of you—the villa, no more than fifteen yards away, nothing but a massive shadowy blur. He would wait out this round of storms, maybe try to close his eyes. If I lie down for half an hour, girding myself against the worst, he reasoned, I’ll be better equipped to venture again into the night.

With the eave of the roof shielding him from everything but the ribbons of blown rain, he put his key in the door and stopped to look at his watch for the first time since slipping it on earlier in the night: 2:59, the witching hour, the setting for every dark night of the soul. He swung the door open, and as he stepped into the narrow corridor found his path dimly lit by a lamp from deep inside the room. Had the maids come to turn down the bed and left it on? Had someone, Famosa Garcia or another of Mateo’s minions, broken in and tossed the room? He felt for the handle of the gun in his belt and took two more steps, then saw her there, kneeling before the bed, her face pale in the artificial light, awash in dread. She scrambled to her feet. He couldn’t fathom what had just happened. Nevertheless, relief surged through him, waves of it pounding his ribs from inside. She was all he’d ever wanted in life, he sometimes still believed that.

“Scott, I was worried about you,” she said feebly, plaintively. “I didn’t know where you were.” But that couldn’t change any of the basic facts concerning what she’d put him through these past twelve hours, which felt much longer than that, which felt like many episodes of disaster strung together and replayed before his eyes in unrelenting memory. She held her ground, though, demanding information. “Why did you stay out so late?”

Next: Chapter 12.

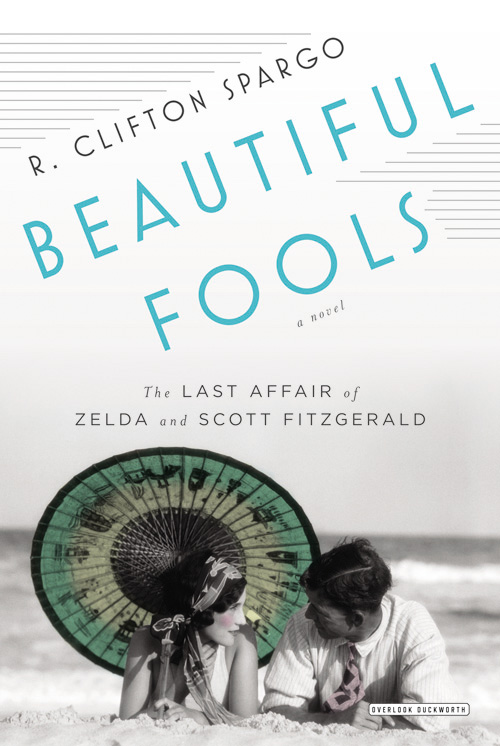

Published as Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald by R. Clifton Spargo (NY. Overlook Duckworth, 2013).