Beautiful Fools

by R. Clifton Spargo

8

IT WAS THEIR BEST DINNER IN CUBA SO FAR. SHE HAD ENJOYED THE PARGO frito, a blue snapper indigenous to Cuban waters, garnished with mango and scallops and served with a creamed plantain soup, while Scott managed to swallow a few oysters and to pick unambitiously at the large crab on his plate. The town was small, not a great many dining options, but she delighted in this quiet restaurant overlooking a lagoon, several dunes and a nearby bank of trees separating them from the ocean, the surf audible whenever the winds relented and a hush fell over the otherwise chattering pines and palms.

“What are the chances? I wish you would invite them to join us for a drink when they finish their meal.”

“Are you still talking about those two Europeans?”

“I didn’t question your taste in friends back in Havana.” He was about to challenge this assertion when she amended the statement: “At least not until I’d given them a chance.” Then also added: “And I’ve said nothing about the Saturday trouble those friends got us into.”

“What does that have to do with anything?”

“It’s my turn, that’s all.”

At the table nearest to them sat the very couple she’d spotted earlier on the beach. As the waiter cleared plates, Scott glanced at her to assess whether her heart was truly set on this latest whim.

“It is, Scott,” she said. “Let me plot this little piece of our adventure.”

“We’ll order another round while I think about it,” he said, but she could always tell when he was going to give in. It had been a good day overall. He hadn’t taken a drink until they sat down to dine. Their conversations had been even and cooperative, neither of them allowing a desperate pitch to enter their repartee. He appreciated the ocean almost as much as she, its soothing effect.

“But don’t think about it too much, Scott. The worst that can happen is they say no.”

“And you’re sure it won’t bother you, that you won’t feel rejected?”

He raised his hand to catch the waiter’s attention so that he might order another rum over mint leaves and sugar, a Cuban specialty neatly suited to his insatiable appetite for liquor and sweetness. The waiter offered to replenish Zelda’s half-full glass of wine from the carafe in front of her, but she lifted her hand to say no.

“Also, por favor,” Scott said as the man turned to leave, “we would like to buy the couple at the next table a bottle of wine. Your house favorite.”

Zelda rested her fingertips on Scott’s forearm, applying gentle pressure.

“Don’t you love the smell of this place,” she said. “Don’t you love how modest and unassuming everything here is. It’s like Cap d’Antibes all over again, right after the Murphys discovered it and invited us for the summer—nothing’s gone wrong yet, no crazy people, no dead children. Poor Patrick, I wept so long for Gerald and Sara when I heard. The losses of those two lovely children are always with me and I pray for them almost every night.”

Scott expressed dutiful sympathy, but he didn’t like to talk about the death of children, especially poor Patrick, who had lost an eight-year battle with tuberculosis.

“Excuse me,” the man from the next table interrupted, addressing Scott. “Right now for me is very, very nice feeling, this gift you bring us, and I wish somehow to say thank you.”

“Oh, please.” Zelda rolled forward in her chair, twisting to face the stranger. He was even more striking now that she saw him up close, with a strong equine jaw and deeply inset brown-black eyes. “You must come sit with us and tell us all about yourselves.”

“It’s not required,” Scott said. “It’s merely an invitation. You’re free to keep the wine either way. But my wife would like to meet you, if you’re in no hurry to be off for the night. She thinks you make a handsome couple.”

“No, nothing secret, nothing magic,” the Spaniard said. “I will implore my wife.”

The couple, Scott and Zelda soon learned, were newlyweds on honeymoon at the resort, but after a glass or two of wine they admitted to being exiles, he a refugee by necessity, she by choice, her choice predicated on love for him. The man was in his late thirties, the wife roughly a decade younger. He had fought in the Spanish Civil War, wounded above the knee in battle, already knowing that his unit of gudari must soon surrender to the Italians, he among the first wave of refugees to cross into France even as his fellow Republicans fought well into the present year, refusing to lay down arms until this past month. But for him the war had ended long before that. Detained on French soil, in Camp Vernet in the Pyrenees, imprisoned for weeks in squalid conditions, he remembered a distant cousin near Lyon whom he’d met only once before while she was still a child and he a young man touring Europe, visiting relatives en route to Paris, aware even at the time of the impression he made on an altogether impressionable girl. In letters mixing Spanish and French, he invoked the memory of his long ago visit and chronicled his forsaken revolutionary aspirations, his love of his country, and the squalid conditions of the camp. Appealing to her fine sensibility and good-heartedness—she was known as a nurse and a humanitarian throughout the extended family—he asked if her parents might vouch for him and get him released into their custody in France. It was too risky to return to Basque territory, he wrote in sincere French, and she memorized his words—“Ce n’est pas prudent pour moi de retourner dans ma patrie”—rightly intuiting that his life was in danger.

Since hers was not a wealthy family, nor one with contacts in government, she made the only move left to make, all for a man she’d met once in her entire life. Already working in Lyon as a Red Cross nurse, she petitioned to get herself assigned to Camp Vernet.

“This was a big fortune for me,” said Aurelio Lopez. “I feel all pain in my leg, but I don’t know what is the problem yet. Seems like it was in the muscle first, then in the bone, which means I was pushing hard when I walked and always it gets worse and worse; so I was able to continue, but it will depend, I tell myself, on whether cualquiera de los santos, if just one of the many saints, you understand me, watches out for me.”

“Instead it was me,” Maryvonne said modestly.

“Better than a saint,” he said, smiling.

Zelda sipped her glass of wine, newly poured from the bottle Scott had purchased for the couple, her own carafe still three-quarters full, as she studied her husband, pleased to find that he was entranced by the tale.

“Tell me about the conditions of the camp,” he said.

“Il n’y a pas de mots pour ca,” Maryvonne replied. Simply beyond words. Men slept in the open, without tents, huddled in small circles around fires, only their blanket capes to cover them. They ate carrion, they ate dead mules, once in a while they ate a rabbit someone caught or a smuggled-in chicken to stretch their meager rations of canned food. All of them far too thin, worn down to the bone. The trees on the rocky hills long ago ravaged of leaves and branches for use in bonfires. It was a landscape not unlike Armageddon.

“Of course, she never see the wars,” Aurelio said, interrupting. “If it rains, if the rain is there and the day is cloudy, and then it rains many more days without stopping, the hills turn to mud and there is no place to sleep. Everything is water, everything is mud. This is life in the hills, this is life in the camps often also, only no more bombs tearing up the countryside. Now it is only hunger and disease and injuries that will never heal. Sometimes it is very bad, but I am thankful not to be in the war. We lose this war and I lose my country, this breaks my heart, but also I do not wish to fight anymore. If this is the will of God, I cannot say what is wrong or right. I do not have nothing against him. It was nothing against him.”

“Perdon, lamento interrumpir,” the waiter was saying. “El restaurante esta cerrado.”

“Oh, that’s impossible,” Zelda cried. “We’re not even done with the bottle of wine.”

“You must come back to our bungalow,” Maryvonne proposed. “For a nightcap, yes?”

Scott and Aurelio rose from the table to settle the bills, Aurelio insisting that the waiter allow them to purchase a bottle of wine to take with them. Rejoining the women, the Spaniard seized the unfinished bottle and motioned for Maryvonne to pilfer the carafe and glasses as she wrapped the contents of the bread basket in a napkin to stow it in her bag.

“It is not a long walk,” Aurelio informed them, so the two couples took to the shore, where the waves rolled in under a sky bright with stars that made them feel strong and safe.

Trailing the European couple whose habits were those of refugees, salvaging always what they could, unwilling to relinquish new friends or a night’s revelries, Zelda considered that she and Scott had once fallen into many of these same habits, albeit for different reasons. The Frenchwoman, easily annoyed by their every attempt to deploy their rusted cosmopolitanism, responded in English to the queries posed in her native tongue. The only French they could elicit from her was the rather ill-tempered command to switch to a language everyone could speak: “Mais je ne comprends pas, s’il vous plait le repete, en anglais.” It never occurred to her that they might likewise complain of her use of their native language, her vowels so curled and elided that the lag between her pronouncing a phrase in English and their making sense of it was considerable.

“I made a resolution at the restaurant,” Zelda whispered to Scott as they plodded through the sand. “I promised myself to adore this couple, they are so lovely and have so much potential, but her superiority is testing my resolve.”

“I thought by now,” Scott quipped, “you would be used to the tyranny of the French.”

Overhearing those words but misunderstanding the reference, Aurelio lamented, “Well, what you say is true, now France is also a dictatorship.”

He condemned a recent vote by the French National Assembly to cede all powers of state—the right to build up the military and air force and leverage the funds to do so; the right to engage in preemptive tactics in anticipation of German aggressions; the right to wage war against Hitler on all fronts when the time came—to Prime Minister Daladier.

“Such a decision is momentane,” Maryvonne said in defense of her homeland. “We face enemies without scruples, who do not keep their word from some month to the next. I do not see what decision, that my country had a choice, Hitler takes away our choices.”

“Yes, the French now prepare to do what is necessary,” Aurelio said, “but what if that time has passed already?”

“After the Great War,” Scott remarked, “I set myself against all wars. No more war in my lifetime. But Fascism is not politics, it is a mode of perpetual warfare against the vulnerable, Jews, Czechs, the Basque people—”

“Politics as war by other means,” Aurelio said.

“It can only be defeated,” Scott continued, “by armed opponents, I’m afraid.”

“I do not see how you are going to be so critical of my country,” Maryvonne said, addressing herself to her husband, nationalist pride creeping into her voice, “a country that have provided you refuge when, without refuge, you surely will be dead.”

“I find fault with the French government,” he answered diplomatically, “but not her people. To me the French people are you, faultless, generous, someone to whom I owe my entire life.”

Zelda wanted to hear more of their story, what had happened after Maryvonne found her handsome cousin near death in a refugee camp.

“I wrote letters to my government lamenting conditions,” she said, but it was unclear whether she was addressing her husband’s criticisms or moving on to speak of his escape. “So many letters, without ever a reply.”

It was up to Aurelio to explain how Maryvonne had nursed him back to health, never letting on to her superiors why she dogged the overworked doctors to make sure they tended to an anonymous Spanish soldier. Her brother helped her smuggle provisions into the camp, for Aurelio as well as several other soldiers in dire condition: rainproofed tents, deloused blankets, fresh dressings for wounds, tea, cigarettes, rations of sardines. Already the authorities were relocating Jews and Communists to camps farther inside of France, repatriating Basque farmers who were less than deeply committed Communists under a guarantee from Franco that after being reeducated they might return to their homes. But Maryvonne knew that her cousin could never pass for an ignorant Basque farmer. For men such as him, the prospects were dismal. They had nowhere to be except on that barren borderland. Still, guards could be bribed, if you had money and means, some help from the other side of the barbed wire, maybe also the know-how to embed yourself, once you were inside mother France, in the country’s interior.

She arranged it all, exhausting her paltry savings, bribing a guard to look the other way while her brother smuggled Aurelio out of the camp in a supply truck and escorted him to her family’s modest farm outside Lyon. Only days later she resigned from the Red Cross and joined her cousin. Every member of the family, including her brother, assumed she would never have gone to such lengths, even for a cousin, unless she were also in love with him. So after a week of prodding innuendo from her mother, sisters, and brother, she approached Aurelio and said, “Since everyone believes we are to be married, I propose that you marry me”; and marry her he did, in a modest ceremony in the village, allowing him to elude notice of the ever increasing, rabid minority in France who were hostile to all resident aliens.

“Oh, stop here,” Maryvonne exclaimed as they neared a row of spaciously set-apart stone cabins ensconced in a grove of Australian pines that abutted the silver-sanded beach. She directed attention to the moon, lying low on calm ocean waters, the lights out in all the cabins except one, so that it was impossible to tell whether they housed sleeping guests or revelers who hadn’t yet returned home. It was just shy of midnight, not especially late for a country participating in the rites of siesta and the recalibrated inner clock that followed from the introduction of second sleep into everyday existence.

***

Maryvonne pulled the radio as close as possible to the small patio door, spinning the dial for a station, while Aurelio dragged chairs from the cabin so his guests could enjoy the sultry ocean air. The announcer now and then peppered his comments with English, reading an advertisement for cigarettes before introducing a song that Zelda recognized right away. Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag, and smile, smile, smile. While you’ve a Lucifer to light your fag, smile, boys, that’s the style. It was from a war movie made this past year starring Jimmy Stewart and Margaret Sullavan, in which she played a Broadway singer whose soldier husband gets killed in battle, and after receiving news of his demise, she must take the stage and sing this cheering song.

“I love this song,” Maryvonne said. Zelda doubted a Red Cross nurse from France could be aware of its association with the movie, since, in that case, the lyrics would surely have troubled her more. “Everybody must dance to this song.”

Maryvonne walked over to Scott instead of her husband.

“Mr. Fitzgerald, you would be so kind?”

Before Zelda could search Scott for his reaction—he might be flattered, he might be irascible, it all depended on how his lungs felt, whether the drinks had restored or drained his strength —she felt a man’s grip on her elbow, as firm as his voice: “We have marching orders.” Zelda allowed herself to be lifted from the chair, the glass of wine extracted from her hand and placed on the ground as the Spaniard pulled her into his arms.

Swaying to the jaunty, marching, military pomp of the song, she gazed over the Spaniard’s shoulder at her husband, who though slow on the uptake had accepted the Frenchwoman’s invitation without protest and now stylishly pulled her through lush, tight waltzing squares. Zelda, chin resting on another man’s shoulder, took simple pleasure in the song. What’s the use of worrying? Sullavan sang with warbling steadfastness, her voice milking the contrast between what the words recommended and what she must really be feeling. It never was worthwhile, so pack up your troubles in your old kit bag, and smile, smile, smile.

When the song finished, Aurelio escorted Zelda to her chair, topped off her glass of wine, and offered a cigarette, which he then lit for her, asking where she had learned to dance so well.

Maryvonne complained about the cool night air and Zelda suspected that Scott had put her up to it. So the couples pulled the chairs inside, where they resumed drinking and smoking, dancing now and then to someone’s favorite song, the room muggy and claustrophobic. Aurelio hung at Zelda’s side, doting on her, and she felt suddenly self-conscious—about lost youth and lapsed social skills, about the roughened texture of her face—unable to receive his stare without glancing away. It occurred to her for the first time that the European couple (theirs was a marriage of convenience, after all) might be in earnest about swapping partners. She watched Scott enjoying the young woman’s flirtatious banter, when suddenly Maryvonne shot to her feet and fled the room.

Aurelio asked Zelda to dance again and she accepted, so the Spaniard guided her through a form of native Cuban dance he himself had only recently mastered. The swift, neat movements, always in a radius of a few feet, the constant retreading of the same ground, intensified the dance’s air of intimacy. Scott stared at them in silence from his chair, perhaps winded from the dancing, perhaps dizzied by alcohol or his weak heart.

“Explain to me,” Aurelio called to him, apprehending the duties of host even as he danced with a guest’s wife, “since we have talked of dictators, explain why is Franco attractive to Americans, also Mussolini—why so many Americans affectionate for Fascists.”

“Not all Americans are soft,” Scott responded irritably, and Zelda feared he might get testy, obsessed as he was by perceived insults, always prepared to defend his maligned honor in fistfights he could not possibly win. “I consider myself to be vehemently anti-Fascist.”

“I mean no disrespect,” Aurelio said.

“Excuse me,” Zelda interrupted, finding it odd that no one had said anything about Maryvonne’s departure. “Is she all right?”

“Why didn’t you try to get back into Spain?” Scott asked. Weren’t there ways to continue resisting Franco from within, just as the Germans must now fight Hitler from within their country? How else would Fascism ever fall?

“I am almost certain to be executed,” Aurelio reported with sangfroid. To go back to Franco’s Spain meant certain death before a firing squad.

“It is in here,” Maryvonne announced, entering the room again and holding up a recent copy of LIFE, “a small glimpse of what my Aurelio suffers.” On the cover a girl in straight blond bangs and ribboned ponytails bore a dour expression, a doll in similar blond bangs and ponytail positioned to her right, making it seem as though the girl stood erect, her arm loosely, even reluctantly enfolding a lifeless replica of herself. To reinforce the effect—Zelda found the photograph discomfiting—the doll and girl wore matching jumpers: short rounded collar, diagonal striping in the style of a cravat except that it was flat and sewn into the dress, a thin waistband in the same diagonal striping. Aurelio tried to spin Zelda through a lift in the song, but she pulled free of him, as Maryvonne flipped through the pages of LIFE, arriving at stark photographs of a camp for Republican refugees such as the one she’d found her cousin in.

“It is not Camp Vernet. What you see in this picture is bad but not horrible,” she said, rolling r’s, elongating her i’s, her accent pulling the word into French. “How would you say effroyable?”

“Outrageous, dreadful,” Scott suggested.

“Yes, it is not full of dread,” Maryvonne replied. “The men do not look as though they are fearing for death.”

She flipped the magazine shut, handing it to Zelda, saying she was welcome to take it home with her.

“Where would you stop your life if you could?” Zelda said a propos of nothing, addressing the young woman. “I mean, if you could stop it, and then keep living at that age, having gained enough wisdom, know-how, and talent to make good use of yourself, enough happiness to stare down adversity—”

Aurelio said he thought he understood what she meant: if you could go on living forever, without aging, without losing will, what Schopenhauer called the “will to life.”

“At thirty-five,” Zelda said, “on my birthday. That’s when I’d stop time.”

“Do not forget to blow out the candle, then,” her dance partner said with a sportive lilt in his voice, “and maybe you will get your wish.”

But there was something artificial in his flattery. He didn’t believe she was shy of thirty-five. True, she had stayed young for so long, far longer than most people were able to manage, indulging only her appetite for experience, indifferent to the taxes imposed on pleasure. No longer, though—too many bouts of eczema and insanity, too many starvation performances that weren’t even meant as such. Now she looked her age, several years past thirty-five.

“On my birthday, three years ago,” the Frenchwoman said. “Before that war,” she added, lowering her voice to a hush.

“It has already begun,” Aurelio said, taking Maryvonne in his arms, dipping her in a mock dance, naming her as his raison d’etre. “All the world does not know it, but even three years ago, the war, it commences already.” Spinning in his arms this distant cousin who was also his wife, who somewhere along the way must have fallen in love with him, he began to kiss her immodestly, the two of them standing in the middle of the room, grinding into each other as if trying to crush some sadness wedged between them. “Besides,” he said, “you would not know me then.”

There was a pounding at the front door and Aurelio disappeared into the small foyer, only to be greeted by a boisterous man scolding in Spanish who forced his way inside. The hotel’s on-duty manager stood in the center of the living room. “Los invitados no pueden dormir aqui!” While waving two fingers at Scott, he spoke only to Aurelio. “You cannot sleep here, he say, unless you pay for your own room.” Aurelio’s translation was unnecessary. Both Zelda and Scott understood the manager well enough. On the trail of raucous behavior, immorality, maybe just pleasure itself, the man spent part of every night policing noise. It was not an easy aspect of his job, but it was his job all the same.

“We’re staying in the main villa, second floor,” Scott said, interrupting.

“Excuse me, senor.”

“Hardly the freeloaders you’ve mistaken us for,” Scott said.

Zelda had the feeling that the manager wasn’t there to prevent freeloaders so much as to break up an imminent orgy.

“Perdon, mi error,” the manager said automatically, but he held his ground, suggesting it might be best if they returned to their room. Other guests had lodged complaints about the noise.

“Which guests?” Scott asked. “I would like their names.” He hated having authority of any kind wielded over him. It made him irate, violent, rash.

“Lo que me pide es imposible,” the night manager said, before switching to English. “Impossible, I can give no names; I can violate the privacy of the guests never, not at any time.”

“It is late in any case,” Maryvonne said. Zelda looked across at Aurelio, but he seemed ready to join Scott in the quarrel.

“Well, we’d like our privacy now,” Scott said to the night manager. “You may wait outside, please.”

The manager, perhaps regretting having labeled guests of the resort trespassers, capitulated and stepped outside. The two couples said their goodbyes, Aurelio pleased by Scott’s performance, Maryvonne professing her pleasure in the night and insisting on meeting again.

The night manager stood under a bull-horn acacia tree, waiting on them, humbler now in manner, oddly contrite about having to break up their party, but it was true, other guests had complained about the noise. It made no difference to him, personally.

“Recent troubles notwithstanding,” Zelda said as they walked across grass and fallen palm fronds, “I enjoyed them, and they’re clearly more appropriate company for us.”

“You’re a snob, Zelda,” Scott said. “Besides, Mateo is from older money than any three of tonight’s party combined, yourself included.”

“True enough,” she said. “On the whole I liked him too. But you can’t blame me for worrying about his judgment.”

“What he did for us cannot be denied.”

She let the remark pass. Enough of that, no bickering, she wanted to talk about how much she had enjoyed tonight, how charming and knowledgeable Scott could be, how calmly he’d put that manager in his place. Did he think it likely the girl Maryvonne had a crush on him? Scott said she was hardly a girl, and he hadn’t noticed anything except Aurelio’s doting on Zelda. “But his wife’s so much younger than I am, what could he see in me?” Maryvonne was in her late twenties, Scott said, pushing thirty, hardly a young girl anymore. It felt like a huge divide to Zelda—a decade was such a long time in a woman’s life.

“I like it when we do things,” she said as they followed the path back to the villa. “We don’t go on outings often enough, maybe that’s why we forget how good we can be together.”

She didn’t mean it as criticism. To make this clear, she pressed herself against his flank, inspiring him to wrap his arm around her waist. She hardly noticed the ocean, never more than thirty yards away during their homeward stroll, but she could taste the salt air going into her lungs.

Inside their room he sat next to her on the bed. “Why did you choose that date, of all years? It was such a bad year, the year you turned thirty-five; you suffered so, you were so far gone and I wasn’t sure you—”

“You were still mine,” she said.

He grew quiet.

“It was the last time I truly believed, that is, when I was well enough to think or believe anything—”

“But you believe in so many—”

“It was the last time I believed—your promises were so earnest, desperate, mostly you were saying what I needed to hear—but still it was the last time I felt sure we would get there.”

“Maybe we’re here now,” he said, slanting forward to kiss her as she fell back on the bed to receive the sturdy weight of a man’s body on top of her, his hands stroking her face, her shoulders, her breasts and neck, fingers gliding along the satiny surface of her dress, his movements gentle but purposeful. Shivering to his touch, she anticipated where his hands would go next, as delighted when she was wrong as when she was right, waiting, waiting, enjoying the wait and the way it filled up everything. She wanted his hands on her skin. At last he was unzipping her dress, saying, “Hold on to my neck,” so he could lift her torso off the bed and peel the elegant charmeuse gown from her shoulders, as far down as her waist. She rolled sideways on the bed, throwing her legs out until she was standing beside him on the floor, his cue, which he took immediately, to pull the dress down over her hips.

There were times, especially in recent years, when their lovemaking was halting, bungled, clumsy, always one or the other of them on the verge of feeling wronged. On more than one occasion she had accused him of being unskillful. Alcohol got in the way, also her prickly nature, also her expectation that he should know without any prompting what pleased her. It was a mode of magical thinking, the belief that men were supposed to be naturally skillful, able to intuit a lover’s every desire. She had a hard time forgiving him when they fell out of sync, fearing that it was some kind of comment on their basic incompatibility. But not tonight, tonight his moves coincided with hers, what he wanted to do next aligned with what she also desired. She was naked, only her hat still on, pinned to her hair for a bit longer anyway, and he stripped himself while continuing to caress her. Soon all he wore were his socks, which she slipped off with her feet. She felt his penis, firm, unambivalent. “Oh, you feel so nice,” she said, sighing, arching her back on a pillow, rolling her hips upward to press into him, curling her fingers up and over the helmeted tip of him, applying pressure on it and rocking into it until in one swift, straight motion she pulled him inside.

When they were done she rolled from the bed, walking into the bathroom to wash her face. And after that, without understanding what she was doing or why, she began to pace the room while Scott, worn out on the bed, now and then coughing in his groggy sleep, made vague inquiries into the dark as to whether she was all right, whether she was coming back to bed soon.

“I’m just so happy,” she said, still pacing. “It will be fine, I’ll calm down, I’ll come back in a minute.”

***

In the morning she woke him with breakfast and a gift, throwing herself beside him on the bed, announcing that she had been up for hours and found a market in town—in fact she’d run into the Frenchwoman from last night, Maryvonne, and they had talked and shopped together. Before Scott could open his gift, he had to eat something. Either the fresh guava or one of the baguettes she had purchased. Either a red banana or one of those whose surface was mottled like a snake’s skin. Last but not least, there was a Hershey’s chocolate bar. Knowing how he craved chocolate, she held it out as a reward, so that he would take at least one bite of each item of real food, which was exactly what he did, one bite of each kind of banana, one bite of a baguette, maybe two or three bites of the guava, before devouring the chocolate bar.

Now it was time for her presentation.

Zelda was in the habit of interpreting the presents she gave to people. It enhanced the pleasure of gift-giving, the opportunity to explain the thought she put into the choice of an item, why it was exactly what Scott, Scottie, or her mother needed. She told him how she had borrowed pesos from his wallet for the food, but the gift was purchased—she watched him unwrap it and, oh, she was so sure he was going to like it—with money put aside from her discretionary fund at the Highland, saved specially for this trip so she could purchase a few items for loved ones.

What Scott held in his hand was a small silver medallion, a religious icon.

“It’s Saint Lazarus, dearest Dodo, do you remember him?”

“Of course I remember Lazarus.” Scott said. “What is he, the patron saint of coming back from the dead? Did you think he might bump start my career?”

“Be serious, please,” she said. “He takes care of the sick, and you need to remember that your lungs and heart and overall health are more precious to some of us who walk this earth than they are to yourself. Since you won’t look after you, I found someone who will. Soon we’ll find a chain, and as you wear it you’ll think, I must take better care of myself. Meantime we can attach it to this piece of hand-braided twine so you can get used to it.”

“Zelda, you can be so sweet,” he said leaning forward so that she could drape it over his neck. “Is there anyone as sweet as you?”

She laid her head on the pillow next to him, staring into his eyes, their noses inches apart.

“Will you remember this, Scott? If I die tomorrow, say you’ll remember and write about it, because I don’t want them saying I was a narcissistic person. I know sometimes I’ve been hard on you, but tell me you remember all the kindnesses too.”

“Of course,” he said. “I always do, but Zelda, no one’s—”

“You promise?” She jerked her head up off the pillow, propping herself up by her elbows to stare down into his eyes. “Do you promise, Scott?”

“What’s this about?”

“Nothing, really, I just need you to remember. I had a dream last night, it’s silly.”

In her sleep she had suffered a vision of how she might be seen—how literary men and biographers would talk about her. She knew what Ernest said about her already, even to common friends such as Gerald and Sara. She knew what John Dos Passos and John Peale Bishop thought. And there were others, of course. She wasn’t blind, she wasn’t deaf. Now that she had spent all these years in sanitariums and hospitals, unable to procure her freedom, the naysayers would have all the proof they needed. What was everybody else to think? She would always be “poor Zelda” to the masses; maybe Scott himself took comfort in the arms of lovers while referring to her as his “poor Zelda,” but she didn’t want their pity. She wanted to be remembered for the things she had done for him, for the joy he obtained simply from being in love with her. She was special, she wasn’t like other people, he was lucky to have known her.

“I’ve never said otherwise.”

“Then we’re agreed,” she said. Because she had made plans for them while he slept, and, yes, it involved their friends from last night, but that was all she would say for now. Did he approve? They were to leave in an hour. When he raised no objections, she began to talk again of the gift.

“Do you see the two dogs at his feet? It’s from a story in the Bible, about the beggar Lazarus eating with the dogs. He’s always depicted that way, since the Middle Ages, the old woman at the market told me. But here in Cuba he is special for the Africans also because he resembles an old Yoruban god, Babalu-Aye, I think he’s called, who tends to the wounded, who heals the chronically ill, who oversees health in the family. I want you to wear this medallion, and your lungs will get better and no harm will come to you.”

Scott extended his palm to clasp her by the neck so that he might pull her lips to his, but she jerked away.

“Say you’ll remember,” she said.

Next: Chapter 9.

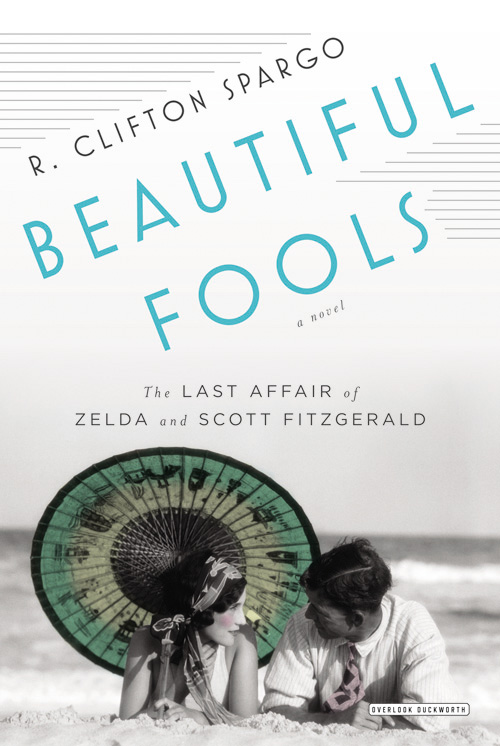

Published as Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald by R. Clifton Spargo (NY. Overlook Duckworth, 2013).