The Disenchanted

by Budd Schulberg

16

“Know what the trouble with this drawing room is?”

Shep didn’t bother to look up. “Don’t tell me. We’ve got enough troubles.”

“Trouble with this drawing room is we gotta leave it in a couple of hours.”

Manley Halliday was sitting on the long side seat with his head bent almost to his knees.

“You better stretch out, unbutton your shirt, Manley.”

Shep was worried about the pallor. It wasn’t a dead-white any more, but discolored as if by jaundice. And there seemed to be no color left in the eyes at all.

“They’ll be serving breakfast soon. I’d better take my shot. Wish I could remember when I took the last one.”

He had to use the rim of the upper berth to pull himself to his feet. The few steps to the washroom were precarious. Once the lurch of the train almost pulled him off balance and Shep jumped up to break his fall. Manley Halliday tried a sallow smile and said, “I’m all right.”

Shep said, “Well, you don’t look all right. If there’s anything I can do …”

“There is one thing,” Halliday admitted. “If that happens again—like on the plane—you might sort of keep an eye on me.” Again, without smiling, his voice used the tone that goes with smiling. “I been a good ol’ wagon, but baby how I done broke down.”

When Manley Halliday emerged from the washroom his eyes appeared brighter and he could stand more erect.

“How much time ’fore we get in?”

Shep looked up hopefully. Behind the crumpled clothing, the stubble of beard and the bilious complexion his man sounded a little more pulled-together.

“ ’Bout two ’n a half hours.”

“I’ve thought up lots of plots in two ’n a half hours.” “Well, brother, we could use one now. That camera crew’s gonna be on us like wolves the moment we come down the platform. I can hear Hutchinson now, all full of p. and v. saying, ’We’re ready like Freddie—where d’we line up first?’ Manley, are you listening to me? This is our last chance. Absolutely our last. We’ve got to do it now or get off the pot.”

“All right.” Manley Halliday made it sound like a turning point. “Le’s each have another inspiration tablet.” He passed the benzedrine. “We’ll sleep when we get back to New York. Now le’s rise to the occasion. All ready—one, two, three—rise——” “Maybe you think it’s funny, but I want to keep this job.” “Young man, you have the word of an old clown, I don’t think it’s a bit funny.”

“Okay, then what do you say we cut out the comedy? You know, you haven’t come up with an idea since we started this damn thing.”

“All right. All right.” He assumed an expression of intense conscientiousness. He was thinking and at the same time trying not to think. “Now let me see. Let me think. Let me stick in my thumb and pull out a plum and say what a good hack am I.”

Shep watched him shut his eyes, reaching in, making himself think Love on Ice. “My God, I see it!” “Okay, let’s hear it.”

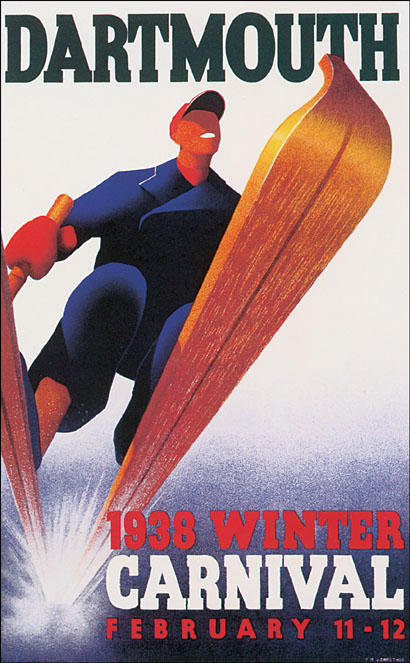

When Manley Halliday began to speak, it did not sound at all like the presentation of a fresh idea. It seemed a kind of self-hypnosis, an uncanny playback of something recorded long ago. “I see it. I see a white fairyland in the Green Mountains. The steep white hillside falls away into a broad valley, as in a skier’s dream. In the distance on high a tiny dark figure appears and starts sweeping down toward our camera. Faster and faster he flies over the freshly fallen snow that forms the perfect carpet for the sheer ice beneath. He is the Lone Skier, Youth charging down into the virgin field of trackless snow.” Shep listened in fascination.

“Along the lower edge of the skier’s field runs a winding road. Rounding the corner into view is a handsome touring car—driven by a uniformed chauffeur and carrying a single passenger, a young woman whose face is aglow with the cold of the air and the warmth of being alive. The way only a girl aware of her own youth and beauty can ever feel alive. She is a Princess Solitaire and her blond curls originally molded into an elegant coiffeur that rode her beauty like a golden crown are slightly windblown now. She is snugly bundled in a luxurious fur car-robe and her head is thrown back the better to enjoy the glories of this winter day. As her bright young eyes lift to take in everything, everything, she sees our skier, a breath-taking masculine blur of green against the snow-white slope …”

“Yes … ?” Shep murmured, already half-convinced of here it was.

“At the same time a sudden, graceful Gelandesprung offers our skier first sight of the Girl. In a flash, he sees the pride, the readiness, the lovely out-of-doors flush, the golden curls. Arrested by this vision on the road below, in the very moment of headlong flight, he throws his body in a sudden Christiana that checks his speed from a breathless fifty miles an hour to a breathless zero. His skis throw up behind him a dazzling white fan of flying crystals. Leaning on his ski-poles he stares boldly to see what he has seen.

“On the road the sport touring car has come abreast of him now. Slowly, with her eyes drawn to the figure on the hill, the girl removes a hand from the chinchilla muff under the robe, leans forward and taps the chauffeur gently on the shoulder. The car comes to a stop. She looks up unashamedly, call it even flirtatiously, but the flirtation of a princess allowing herself to be amused by one of her subjects. The passionate whim of a Goddess of Winding Roads Through Winter Mountains.

“For a moment as pure and still as the trackless snow they look questioningly into each other’s eyes across the field of white. In their thoughts they meet, love, marry, age together, die, are buried together on this very hillside, side by side.”

Manley Halliday paused and Shep waited as the sound of the train rushing them on came in like the dramatic emphasis of an orchestra in the pit.

“This moment is only a lifetime. This lifetime is only a moment. Lowering her eyes at last, the Girl reaches forward with poised reluctance and signals the chauffeur that she is ready. In the opposite direction from that of the skier the car creeps into motion.

“With a shrug, a shrug of inevitability, the skier pushes off and begins slowly stemming across the hill toward the road she’s left behind. When he approaches a knoll that will carry him out of sight of love no sooner glimpsed than forever lost, he steals a last look over his shoulder. And as the touring car rounds its turn, the Girl, who is really the Goddess of So-Near-and-Yet-So-Far, a lovely Miss-as-Good-as-a-Mile, this golden creature flings her head for a last half-defiant, half-regretful view of her lost skier.

“Then she drives on into the bright morning, into the future, and he skis on toward other virgin fields beyond, into her past. Boy and Girl forever losing, finding and not keeping, even in Fairyland …”

Shep thought Manley Halliday had merely paused, but when perhaps twenty seconds had passed in silence he looked up inquisitively. It would make a good scene all right, a nice silent opening, and he was eager for the rest.

“Mmm-hmmm, mmm-hmmm,” he said encouraged. “And then what happens?”

“Happens?” Manley Halliday said incredulously. “What could happen? They never see each other again.”

“And that’s the whole thing?”

“Yes. Yes. Naturally.” Manley Halliday’s whole manner cried Eureka. “Well, how you like it? Told you we’d get it, didn’ I, baby?”

Shep wasn’t sure what to say. Was this just another gag projection like the farce of the twelve daughters of the college prexy? But on the plane when they had laughed it through, the amusing idea had shone in Manley’s eyes. But this time, Shep thought, those eyes were serious; they were bright with a sense of achievement that disconcerted Shep.

“Tell me the truth, I surprised ya, didn’ I?” Manley Halliday insisted. “I told you, I have a talent, baby. ’S long as I hang on to it I’ll never go under.”

“You mean that’s it, what you just told me, the whole thing?”

“Sure. Sure! Know what Ann says. Average picture has too much story. Director’s so busy getting rid of a plot he hasn’t time for mood ’n composition.”

“Who’s Ann?”

Manley Halliday looked up in surprise. Hadn’t he told Shep about Ann Loeb? He had done so much talking. Better not bring up Ann any more. That was his secret. Good old reliable secret of Ann.

With an unsteadiness more than compensated for by his new rush of enthusiasm, Manley Halliday stood up and waved Shep to his feet. “Come on, let’s go in and tell Victor.”

“Tell him what?”

“That we’ve licked his old story for him.”

“Manley, know what time it is?”

Outside their window it was no longer night but a transition landscape of pale blue.

“Doesn’t matter. Why not relieve Victor’s mind soon as we can?”

“Manley, I really think we ought to wait. Try to work it out a little more.”

“Details. We c’n always fill in the details.” Through a haze, Manley Halliday smiled at Shep. “Come on, let’s go wake Victor up—tell ’im the idea while the bloom’s still on it.”

“Manley, I—I say no. I don’t think it’s such a hot idea.”

Manley Halliday stared at Shep with astonishment, with indignation. “I thought we were in this together,” he said, striking an attitude that might have seemed funny to Shep under less manic circumstances. “Thought you were going to stand by me.” Shep grabbed his arms. “Manley, you can’t go now. Wait a couple of hours.”

Manley Halliday wrenched free, “All right, summer soldier, I’ll go see him alone.”

He threw open the door and started out.

Yes, it was funny, only it wasn’t at all funny and Shep, after weighing for a moment the idea of letting Manley go alone, sighed and trudged after him into the aisle.

Pushing Milgrim’s buzzer at 5:45 in the morning to tell him the fragment of an idea did not seem to Shep the surest way ofgaining the Great Man’s confidence, especially considering the worse-for-wear condition of their clothing and their minds. But Manley Halliday pressed the buzzer with positive exuberance and even winked at Shep to signal what had become in his mind the end of an ordeal.

After the buzzer had been sounded repeatedly, Shep had just finished saying, “Why don’t we come back around eight?” when the sudden opening of the door brought them terribly close to the sleep-dulled face of Victor Milgrim. Intensifying all this for Shep was the fact that this face at the door staring out at them from the dark confines of the sleeping room bore so little resemblance to the alert and dapper face of the official Milgrim with whom they had been dealing. This face was softer around the mouth, perhaps from the removal of bridge work, and in need of a shave and a wash, a combing and a powdering, it retained little to suggest the polish and assurance, the attraction of forcefulness that distinguished its public appearance.

“Ye-es?” he said uncertainly and then, “Well, to what do I owe this—” undoubtedly meant for some elaborate sarcasm he was too near sleep to develop.

“Victor, we’ve been working all night. We’ve come up with something we’d like to try out on you.”

A faint, ambiguous smile began to animate Milgrim’s face. Well, it’s an outrageous hour to rouse a man from his bed, it seemed to say, but maybe this is the way genius operates; it’s the hacks who rent me their brains from ten to five; takes genius, to strike like lightning at five o’clock in the morning. “All right, come in Manley, let’s hear the brainstorm.” Shep followed Manley Halliday into the drawing room. Milgrim turned on the overhead light. He moved some scripts aside and a contemporary novel his story department wanted him to buy (carefully underlined for him to save precious time by reading only the vital parts) and made a place for them to sit down. He buttoned his pajamas modestly to hide the fat on his belly his tailored suits hid so cleverly and, like a judge getting ready for the bench, seemed to take on authority with the silk lounging robe he drew on. “So you really think you’ve lickedit?” he said. He was sure this is how genius works now. He was feeling better.

“I think it has everything you were looking for, Victor,” Manley Halliday said.

Unable to look at either of them Shep stared through his legs at the floor.

“Good—just what I’ve been hoping to hear—” Milgrim looked at his watch “—even if it has to be at six o’clock in the morning.”

Then, there was an unexpected pause. Victor Milgrim and Manley Halliday looked at each other with less warmth than their voices had indicated. Shep glanced up reluctantly to see what was wrong. It seemed as if suddenly and without warning the crazy flush of enthusiasm had drained from Manley Halliday. Perhaps it was the sitting down that caused this false vitality, ebbing and flowing in a berserk tide, to run out again.

“All right, go ahead, I’m listening,” Victor Milgrim said. “Shoot.”

Manley Halliday opened his mouth, said nothing, and then turned to Shep. “Why don’t you tell it?”

Shep blushed and began to stammer. “Well—I—I guess I—”

Victor Milgrim frowned. “Go on, Manley,” he ordered. “Let’s have it.”

Shep put his face into his hands and breathed into them so quietly he was almost holding his breath.

Inhaling deeply through his mouth, Manley Halliday said it all again, even more elaborately than before, with a number of new details brilliantly improvised, all of it told with such conviction as to persuade almost any listener that this sow’s ear lined like a silk purse was the whole hog.

Hearing it again, Shep was surprised—even a little alarmed— to find how completely he had begun to identify himself with this man—a kind of super-sensitive alter ego able to suffer die humiliation Manley Halliday should have been feeling. That Manley Halliday should go on beating his head against this dull post of a story, lavishing so much on an effort that only grew more ludicrous as the embellishments grew more filigreed, was almost more than he could bear. While Manley Halliday wenton building it up in what seemed to Shep both a parody and a refinement on story-conference technique he wondered whether this was a sign of the persistence of Manley Halliday’s narrative genius despite the most forbidding circumstances or merely a sign of Manley Halliday’s permanent deterioration. Was it the live light of the darting firefly or just the afterglow of the lightning bug dead in a bottle? And listening to the inspired, pointless presentation, he wondered how they would survive the traps that seemed to lie in wait all along their path today.

Yet he couldn’t help marveling at the way Manley Halliday could endow this inconsequential bit of fluff with the impressive qualities of his own artistic attitude. It did evoke a scene, a mood, an emotion. Once he had said it, the Girl, luxuriously bundled under her fur car-robe on the rear seat of the sport touring car, was alive for them. And the Lone Skier was an eternal force challenging the elements and making his own path through the winter vastness.

“And so, true to their own divergent destinies,” Manley Halliday was saying, “as they must inevitably, they go their separate ways. And though they may wonder and want and wish for that second chance to do it differently, of course it cannot be. This last stolen look is forever their last. Since they are a pair of lovers in Never-Never land, how fitting that they should never never meet again.”

Just as he had with Shep, Manley Halliday stopped and waited for his applause like a concert singer.

“Well,” he said exuberantly, “was that worth being awakened for?”

Shep turned his head for a quick study of Milgrim’s face. He saw perplexity there, uncertainty, and yet, and yet it sounded good but with the implausibility, the sense of what’s-wrong-with-this-picture one has in dreams. The truth was, Shep suspected, Victor Milgrim didn’t have the story mind to risk a final judgment. He was the kind of producer who sent the same script to a dozen friends and canvassed them for a verdict.

“Well, how do you like it?” in all innocence Manley Halliday asked.

“Mmm—it’s—well, it’s a start,” Milgrim said. And then as if suddenly realizing that they had intruded on his sleep and privacy to tell him something that wasn’t fully assembled, wasn’t ready to be driven off the floor, he became a little testy. “I’ll sleep on it—I think we’d all better sleep on it. God knows you look like something the—” he blocked a cliche in self-conscious deference to Halliday’s literary reputation “—like you’d been dragged behind the train.”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I have.”

Milgrim gave a hollow laugh. “Let’s see how this—inspiration —of yours strikes us in the morning.”

He rose and with what in the daytime of his charm would have been a friendly pat practically pushed them out into the aisle.

When the door had closed them out Manley Halliday clapped his hands together like a happy child and then tried to hug Shep in his glee.

“What did I tell you! He went for it! He went for it! Our troubles are over, baby. Let’s go back to the room and write it down!”

Next chapter 17

Published as The Disenchanted by Budd Schulberg (1950).