The Disenchanted

by Budd Schulberg

10

The white tile of the Holland Tunnel rolled past them as the airline’s black limousine raced through the enormous artery feeding the heart of the city.

Finally they burst out into the open, into the swarming labyrinth of downtown Manhattan. There were the trucks, the cops, the bars, the stores, the cabs, the reckless pedestrians picking holes through traffic like shabby Albie Booths. There were fruit, all colors, vegetables, hock shops, Italians, Jews and the global hustle of the water front. Here the bright boys and the smart girls from the provinces come to make their fortunes; here grimy, overcrowded streets offer frantic hospitality to refugees from German bullyboys, Irish famine, Balkan wars, Italian poverty. Bagdad and Rome and Paris and London had had it once, but it was all here now, it was all here, from the Stock Exchange to the pushcart market, from Young and Rubicam and millions of dollars a word to Joe Gould and his millions of words in search of a dollar. It was all here now, the money and the power and the brains they employ and their great army of camp followers catching the crumbs from the tables of Voisin and “21”; and another world that lived richly without wealth at the New School and the New Friends of Music and the old-film programs of the Museum of Modern Art; and another by-far-the-largest world rushing back and forth across the island, punch-in punch-out, spiced-ham sandwich and a cupa coffee, knocking themselves or one another out simply in order to exist in one of the cramped compartments of the Great Hive. As they rushed uptown along the elevated express lane, Shep felt a resurgence of energy. As an eye-opener, this city of New York was a bagful of benzedrine.

But Manley lay with his head back on the seat, his eyes closed. His body felt twitchy with exhaustion and from time to time he slipped into uneasy fits of sleep, some no longer than a few seconds, from which he kept wrenching himself desperately.

He was barely conscious of the tedious stop-go progress through midtown traffic, the screeching stop in front of the Waldorf, the bustling proximity of Shep Stearns, the sense of being piloted around the outer circle of the lobby’s vortex. Then a rushing upward through the elevator shaft, an opening of doors and other bits of stylized service from the bellboy, the business of a few coins changing hands; they were deposited in their suite overlooking Park Avenue, each with his own bedroom opening on a central living room.

Shep tossed his coat toward the couch but it slipped off and he let it lie there.

“I’ll probably collapse in about five minutes, but I’m feeling great all of a sudden—all hopped up. How you feel, Manley?”

“Like a million dollars,” Halliday said slowly, “in old Spanish doubloons buried ten feet underground.”

They withdrew to their respective bathrooms. Shep, in an effusion of pent-up vitality, performed some deep knee bends and, a few years out of top condition, was gratified to see he could still touch his toes. His calisthenics were interrupted by a call that warbled uneasily across the suite: “Shep—could you come here a minute?”

Shep found Halliday in the bathroom, sitting on the edge of the tub. He was wearing one-piece BVD’s, the old-fashioned kind Shep had never seen in use. His legs looked spindly, his arms were unmuscular and very white and his knees were bony as a small child’s whose legs are growing too fast. On his left thigh was a red line where the needle had slipped and scratched his skin. “I hate to ask you, but would you do this damn thing for me?” Halliday’s voice went a little strident with self-consciousness. Shep was squeamish about taking the hypodermic needle. He didn’t have much heart for these things.

“I’ve always been lousy at it.” Embarrassment kept Halliday talking. “Broke the needle off in my leg once. Been sort of edgy about it ever since.”

Feeling a little sick, Shep plunged the needle.

“Too bad we can’t trade these old chassis in on new models.”

Shep didn’t answer. He was still a little faint from the business of the needle. He felt a genuine compassion for Halliday’s discomfort, but a more basic reaction resented the older man’s flaw. If he wasn’t up to the trip why hadn’t he said so in Milgrim’s office? In Hollywood it had occurred to Halliday: no matter how nice a young man is, inevitably there must be times when an older man will begrudge him his youth. And now Shep was thinking: no matter how much he understands and makes allowances for him, a young man in good health can’t help despising, at times, an older man who is ailing.

“You must be tired as hell,” Shep said. “We were a couple of dopes to stay up all night.”

Damn it, don’t patronize me, Halliday thought. It is the one thing I cannot bear.

“I suppose a little sleep wouldn’t do either of us any harm,” Halliday said. “I think I’ll try to nap for an hour or so.”

He stretched out on the bed and closed his eyes, but the intense winter light streaming through the ineffectual shades penetrated his twitching eyelids. He rose and drew the curtains. For a moment he thought he had created the atmosphere of sleep. But then, intensified as if by some inner amplifier, he heard the cacophony of the avenue below: the rhythmic a-slosh a-slosh a-slosh of the wheels turning on the melting snow, the clang-acling-aclang-acling of that inevitable loose chain, the constant honking of irritable cab-drivers, the persistent whistle of the doormen. He rose again, groped in his pockets and found some cotton pellets Miss Heath had given him on the plane. Then, with his ears plugged and his head pressed down into the pillow, he tried again. But the elimination of outer distractions only succeeded in intensifying the inner ones. The highlights of this pleasure town pinwheeled in his brain. Where was he now, 50th and Park, once their own special amusement park, their fun house? Every time they threw something, they won a prize. One was so small you couldn’t see it at all but the other had won many frizes. Jere and her limericks. Jere just a few blocks away. He wanted to see her and he didn’t want to see her and—once they had had to be separated for a week when he went home to his mother’s deathbed. He had called her from Kansas City three times a day and each time they had said all the same things over again and at the end of every call he had hung up with the same egomaniacal conviction that no two people could have felt this, no not this, not this exquisite meeting and melting of minds and bodies and dreams. And now, a few years later—he could come to town and not even call her. And there she was, right around the corner. He could be there in five minutes … but there was no sleep at the end of that street. Think of something else. Think of Ann. Ann was one of the few people whose judgment of others he trusted. She could make cool judgments without emotional prejudice. Unusual talent. Most people like to think they have it. Funny thing was Jere’s transparently subjective judgments. If she didn’t like a certain girl it meant the girl had an eye out for him. She was usually right. If she said she didn’t like a man, Manley would guess she was physically attracted to him. He was usually right. “The trouble with you, Jere,” he remembered saying once, “is that you weren’t content just to drink from the Fountain of Youth. You kept leaning over to see your own image in it until you fell in and almost drowned.”

“I wasn’t leaning in to see myself,” he remembered Jere’s saying, “I was trying to fish you out.”

This is no way to take a nap.

He had to get some rest. That trembling of the eyelids was always a telltale sign. I know how I’ll put myself to sleep—he thought of it as a joke—I’ll think about our picture. Once upon a time there was a college boy who invited a waitress out of a diner to a Webster house party week-end etcetera and etcetera and somehow or other she becomes theQueen of the Mardi Gras. Could we freshen it up with a little satire on high-pressure advertising? Each of two rival cosmetic companies wants its model to become Queen. They try to rig the election. I know, its rank, but anyway I’m thinking about it. Shep can’t look at me with those big brown calf’s eyes and beg me to have a try at it. Oh, well, if I’m doing this, I might as well stay up and talk to him, I’m not getting any rest anyway.

He went back to the bathroom, took out a benzedrine tablet and then, with a sense of Ann’s restraining hand on his shoulder, broke it in half. It seemed easier to put on the suit he had traveled in than to unpack the ones Ann had folded into the large case. There had been other times in New York when he had felt such devotion to the creases in his pants that he would not have thought of wearing the same suit twice without pressing. But in recent years he had lost nearly all sense of externals. Perhaps the swing of the pendulum had been too extreme in each direction. Unless Ann removed it he would keep putting on the same shirt for days simply because that was less trouble than taking the pins out of a new one.

Entering the sitting room, he found Shep in his bathrobe hunched over the desk, writing in pencil.

“Got our script finished?” He realized he sounded like Al Harper.

Shep grinned. “I thought it might help us get started if we made a list of all the ideas we’ve had so far.”

“Don’t forget the one with Jeanette MacDonald as ’Dizzy’ Dean.”

Shep stood up and stared out the window. He couldn’t say this to Halliday directly. But he talked up as if he were by himself, rehearsing lines for a play. “Manley, I know it’s easy to kid this thing. Most the time I feel like doing it too. But after all, we accepted the job. Sooner or later we’ll have to—roll or give up the dice.”

Shep had all the makings of a hack, Halliday thought rebelliously. He had the hack’s conscientiousness, the hack’s ability to divide his imagination into watertight compartments. And at the same time he thought—that isn’t quite fair. The boy is right. It is a job of work I’m accepting money for. He himself had been critical of these Hollywood writers who sign long-term contracts and then save their best lines to excoriate the sources of their income. Like any dishonesty pushed to the extremes of logical conclusion, this was a form of insanity. He preferred Shep’s attitude. At least the young man professed an honest interest in the medium. Maybe this would be the new attitude, replacing the cynicism and self-contempt of the writers of his generation who had gone out for a soft touch and had developed a taste and finally an insatiable appetite for soft touches.

“Shep, you’re right. Let’s pitch in and solve this thing.”

He sat down as if he meant business. “This is where we’ll lick our story. A hotel room. No personality. No associations. The traditional refuge of harassed playwrights, suicides, and other desperate men.”

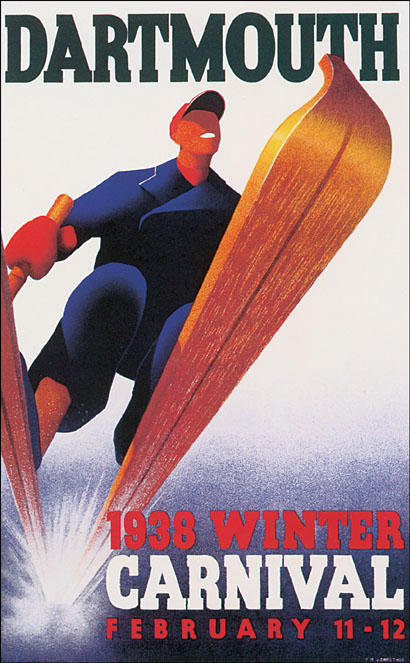

For half an hour or so the room had an atmosphere of righteous labor. As a token of honest effort, Halliday presented his cosmetic advertising idea. It was a small bone to a hungry dog and Shep leapt at it and began to run. The cosmetics model goes up to Webster just to win the Mardi Gras title. Her date, the ski captain, heads the Mardi Gras committee. She vamps him shamelessly all week-end to pull the necessary strings that win the title for her. When he finds out the commercial tie-up he feels like a jerk for having fallen for her. Then, in the finals of the ski-jump, he’s injured. The model, who has been falling in love with him all the time, of course, rushes to his side. Somehow all the commercial big city dross has been washed away by the crisp mountain air and the freshly fallen snow …

“By God, I think we have it!” The anti-business angle even began to embellish it with “honesty” in Shep’s mind.

“Would the boy turn on the girl merely because she was a model for Helena Rubinstein?” Halliday asked. “Maybe we should make that a little stronger. She’s not only a model but the mistress of the sales manager. He’s the real prince of darkness in the piece. He’s come up to Webster as a kind of Iago. He’s a typical product of our age, everything reduced to ’public relations’ in quotes. He still dreams of retiring to the country club with five million dollars, like Charlie Holt—a classmate of mine who bought a seat on the Exchange when he was twenty-six and shot himself in the men’s room of the Exchange when he was thirty-three …”

This time Shep’s sturdy presence blocked Halliday’s trap-door exit to the past. Only a few hours before Shep had been fascinated with Halliday’s double sense of time. He did not go back to the past, he carried it with him. But now Shep had begun to be on the lookout for these nostalgic cut-backs. He began to draw a line between the Manley Halliday whose works had so impressed him and the middle-aged collaborator who could not seem to differentiate between plot analysis and reminiscences.

“This sales manager,” Shep prompted. “You may have something there. He’s a kind of shadow over the week-end. Mmm, how about this? As the climax to his advertising campaign the sales manager wants to stage a mock marriage. You know, just pictures for a full-page magazine lay-out. Well, it’s after the ski-jump injury—this would be the tag—the boy and girl are straightened out, slip away and what the sales manager believes to be a mock marriage is actually a real one …”

Shep’s enthusiasm, self-cranked and back-firing like a hopped-up Ford, struck a rubber wall of silence and bounced back. Halliday gave him a funny look. Then he said:

“Nize baby, et op all de ice.”

“What—what’s that, Manley?”

“When we didn’t like people that’s what we always used to do—answer ’em in Nize Baby talk.”

For the first time since they met Shep wasn’t sure he was going to like Manley Halliday.

“I see,” he said. But he didn’t. His vision hopelessly normal, he could not see around corners.

As soon as Halliday saw the look on Shep’s face he hastened to explain. “Oh, my goodness. I didn’t mean that. I like you. I like you very much. In fact, you’re the first person I’ve liked since—since I decided not to like any more people. No, good God, Shep, I didn’t mean you. I was talking back to the story, to this ogre of commerce I invented.”

“I thought he might put some life into the story,” Shep held on.

“He would. But the wrong kind. I suppose you could make a real character out of him if you went ahead and developed him

—gave him some shading. So he isn’t just a cipher in a morality play. But isn’t he really an extraneous element? There’s an unwholesome quality about him that leaves an ugly stain on the picture. After all, a college house party is a romantic time. It should be a gay, pretty, frothy picture. There should be a kind of innocence about it, a youthful glow …”

Shep sank down into the couch. “Right now I feel about as glowing as a dead fish.”

Halliday said: “Was I making sounds like a producer?”

Shep nodded. “I thought it was the Great God Milgrim himself.”

“There’s something about the movies that brings out these damn generalizations in you. You never think of doing that about a work of fiction. You know who your people are and you track them down specifically one by one.”

“Manley, that’s what we’ve got to do, get back to characters, same as if you were writing a book.”

“But the trouble is, a book is something that starts inside of you. You work from the inside out. You don’t have to sit down and mechanically invent characters and situations. They’re all there, ready to be released. A movie is just the opposite. It doesn’t start inside anybody. Where was Love on Ice conceived, for instance? Certainly not inside Shep Stearns, though I’m sure you could write your own college story. Not even inside Victor Milgrim. It’s an orphan child born of artificial insemination on a box-office counter.”

At another time Shep might have been amused. But the chances were, Milgrim would be coming in on the next plane. He began to wonder if they were up (or down) to the assignment. He was pretty sure any reliable Hollywood hack would have had it in the bag by now. It was mainly a question of adjusting one’s aim. When Halliday wasn’t shooting way beyond the target, he was firing right into the ground at his feet.

“Christ, I don’t know,” Shep said. “This thing’s beginning to drive me nuts. Maybe we should go back and take a look at that waitress line again. There is a certain human interest appeal in a waitress—a completely ordinary counter girl—competing against those Wellesley and Vassar debs.”

“Completely ordinary except that she’s played by Ginger Rogers.”

“O.K. Ginger Rogers. Ginger isn’t a bad actress. She could play a working-class girl.”

“I see. You want a proletarian heroine, Shep. A pretty little union member. None of these cafe-society fascists. Say, here’s an idea—the poor boy has the waitress up, the rich roommate has the Vassar girl, and it’s Vassar who turns out to be the Marxist. At least that would be more authentic. So the Vassar girl falls in love with the boy who’s working his way through and the waitress, who’s a good little opportunist, sets her sights for the rich boy. Why, that rather appeals to me.”

Shep had a desperate impulse. It was something he hadn’t done since a peerade to Worcester for the big game with Holy Cross. He was going to have a mid-day shot. “I think I could use a drink,” he said suddenly. “How about you?”

Use a drink! Yes, he could use one all right. Champagne had saved the night. Now he could use something to get him through the day. Christ, if ever a man had a good excuse.

Uh-uh. Self-pity Halliday. Damn it, would he go to pieces the first day away from Ann? He’d be damned if he would.

“No, thanks, Shep. I’d rather not. But you go ahead.”

He hoped Shep would decide not to drink alone, but Shep was jittery and at the same time—perhaps still under the stimulus of finding himself with Manley Halliday—expansive. It was still a sort of spree, this being flown across a continent to a great hotel to work on a story with Manley Halliday.

Halliday was pleased with his own moral strength in rejecting the drink. But he was a little dismayed when he heard Shep order a bottle of Ballantine’s.

“Might as well have it in the room,” Shep had said casually.

Halliday nodded and tried to smile, but he was frightened. “Tell him to bring me a pitcher of ice water.” What day was this? Only Friday? And they wouldn’t be going back till Tuesday. Tuesday was a precipitous height rising above him. And he would have to climb all the way. The young man would have to exert special effort to pull him along. But supposing he should lose his footing and slip, dragging the young man down? A long way to fall. Mountain-climbing had always seemed to him a tedious and needlessly hazardous excuse for sport. Tobogganing and skiing had been his speed. He and Jere liked to be carried up and to swoosh down.

Together he and Shep made another pedestrian circle around the stubborn walls of the story. The waiter appeared with the Ballantine’s, soda and ice. “Gut morning, chentleman,” he greeted them and both of them could feel his obsequiousness filling the room.

Halliday glared at the intruder. “The ice water?”

“Ach! Ice vatter. I haf forgotten zer vatter.”

“Yah. Zer vatter,” Halliday mocked.

Shep frowned. The waiter looked unhappy. “From zer zink maybe …” he began hopefully.

“I want a pitcher of water,” Halliday said sharply. “And mach schnell.”

More like a rabbit than the walrus he resembled, the waiter scurried off.

Halliday chuckled maliciously. But Shep was appalled and went into action.

“The poor guy. I always feel sorry for waiters.”

“I feel sorrier for writers. Waiters in big hotels probably make more money than you do. They’re the trickiest people in the world, with the possible exception of Hungarians. And when you get the two together you’ve got the New Machiavelli. Shep, I’m going to have to get you over this ridiculous notion of sentimentalizing everybody. Most of us are swine. But when it comes to German waiters in big hotels, I tell you there are no exceptions.”

Shep poured himself a big one and held up the bottle as an invitation. “I’ll get you some water from the bathroom.”

“Well …” Desire and reason staged a brief, unequal tug-of-war. “… a very, very short one.”

Ah, he had a glass in his hand again. It had happened so easily. He was hardly aware of how it had begun.

It was good though. Even before the touch of the rim to his lips, the fumes whispered relax and promised euphoria. He drank thirstily. Shep had taken him too literally. It was good but not strong enough.

The waiter arrived with the pitcher. Manley regarded him slyly.

“How long have you been in this country, Adolph?” The waiter looked miserable. “Excuse me, pleece. My name iss not Adolph. It is Yoseph.”

“You wouldn’t be ashamed to be called after your leader, though, would you?”

Manley was questioning him with theatrical severity, as if he were playing some official role, an FBI man perhaps.

Watching the waiter redden, Shep felt miserable for all of them.

“He iss not my leader, zer. I am American Zitizen.”

“So is Fritz Kuhn. But I know you people. Ein Führer. Bin Volk. Ein Staat.”

The waiter’s face screwed up as if ready to burst into tears. He had wondered when this would begin.

“No, no, I am gut Zitizen.”

Manley poured himself a second drink. He poured it recklessly, without measuring. Shep watched uneasily. It hardly seemed possible that Manley could be in the bag, and yet there was an unfamiliar edge to his voice, a combative look in his eye. And see how his hand trembled when he tried to hold the lip of the bottle to his glass. Of course that could be merely fatigue on top of illness. But these wild things he was saying:

“Tell me the truth, Yoseph, you felt pretty proud of yourself the day your schone Knaben goose-stepped into the Rhineland, didn’t you?”

The waiter’s eyes rolled toward Shep. “Chentleman, pleece.” He was trying to edge his way out. “If you zhould vish somet’ing more …”

But Manley would not, perhaps he could not, let go. “Our country’s too soft. Like Athens, we’ve got to be destroyed. When we let suspicious characters like you run around loose, in a big hotel like this, a gold-mine for espionage… And who thinks to notice a waiter? They’re like part of the furnishings …”

This was too much even for Joseph’s habitual docility and he broke into an emotional protest, an outburst of anger choked by shrill self-pity.

“Nein, nein, das ist nicht wahr—” In his excitement, after sixteen years he could hardly remember his English. “Ich bin—I am not spy. I gut American Zitizen. My zon Hans has four months already in the American Army. You haf no right to say spy of gut American Zitizen.”

“All right, all right, Joe, he was only kidding. Beat it, forget about it,” Shep said.

Joseph retreated behind a rear-guard defense of muttered denial.

Shep looked at Manley carefully. What he saw was deceiving. Manley certainly did not look as far gone as he sounded.

“Manley, I hate to say this, but—that was a silly goddam thing to do.”

“Why—what did I do?” He was really bewildered.

“Picking on that poor guy like that. Sure I’m all for the Nazi boycott but we can’t start baiting every German we meet. Next thing you know you’ll be kicking dachshunds.”

“Oh, my God—is that the way it looked?”

It was slightly ludicrous the way he lowered his head. The small boy scolded by his father. “Lord, baby, you’re right. I guess that was a wet thing to do.”

He jumped to his feet. Shep was still watching him carefully, wondering what he was going to do next. Manley ran across the room to the corridor door.

“Where are you going?”

“Catch the waiter, ’pologize. I’ll give him some money.”

Shep tossed his drink down and paced the room nervously. In a few moments Manley was back. He was no longer a member of counter-intelligence. “He had gone down already,” he said, self-chastised.

Feeling almost too sober, Shep built himself another drink. He hesitated to freshen Manley’s. But afraid to patronize him again, he said how about another.

“No, thank you,” Manley said. The business of the waiter had frightened him too. Just can’t drink any more. Not since I was dealcoholized. Got to be careful now. Damned careful.

Shep was trying to talk story again.

“We’ve got to bear down now, Manley. Jesus, Milgrim will be on our necks any minute.”

The story. The waitress. The roommates. The misunderstanding. The ski finale. The big clinch.

Manley stood at the window, thinking of the city.

“What if the waitress had a baby?”

“What?”

He didn’t have to look around to see the annoyance in Shep’s face.

“I see her on an ice floe with her baby. The ice is beginning to crack. The Webster skier comes by and she throws the baby across the widening chasm into his arms.”

Shep couldn’t think of anything to say. He stared morosely into his glass.

“I was just trying to get away from all the generalizing,” Manley tried to bridge the silence. “Trying to think up a good movie scene.”

Is he kidding me? Is he drunk? Is he out of his mind? Shep felt himself being hemmed in by terrible alternatives. For the first time since they left, he saw the gargoyle face of fiasco grinning down at them.

“Maybe we should both go douse our heads under a cold shower, Manley. And try a fresh start in half an hour.”

It was the most tactful reprimand he could summon. The willful boy in Halliday seemed to recognize it for what it was. For he answered, “Go ahead, you shower if you like. I think I’ll catch a breath of fresh air. Meet you back here in half an hour or so.”

“All right—” For the first time, Shep actually welcomed the chance to get away from him. This was the seventeenth consecutive hour without sleep, without rest from each other. “—but don’t get lost, Manley. We’ve got to get our lumps in on this damned story this afternoon.”

The homburg seemed to restore Manley’s dignity. The crisp “See you anon” was more in key with the famous-author-and-ardent-young-fan relationship of the day before yesterday.

Shep said a dull s’long. He hated this feeling of nagging wife. Get home early, dear. He noted, with what seemed almost a wife’s loving disapproval, how Manley staggered slightly on his way to the elevator.

As soon as Manley reached the sidewalk the winter air took care of that heavy feeling behind his eyes. For the first time all day he felt New York, the rush of cabs, the correct doorman, the Park Avenue wives chic and aging in their furs, the beautiful blue poodle in the arms of the beautiful blonde girl on the arm of a dapper fifty-year-old Park Avenue blade. For just one moment he loved it all again. He felt free, absurdly, boyishly free. Just as on the day he had come down from school to meet Mother and her train had been late. That was one of his first memories of the luxury of time that does not have to be accounted for. Sometimes he wondered if all luxuries could not be reduced to this single formula. For an hour or so he would be free of World-Wide Pictures, of Victor Milgrim, of Shep Stearns, of Hollywood, of responsibility. He took a malicious, vengeful glee in throwing the young man into the pot.

It was only when he turned off Park Avenue toward the East River that he realized where he was going. His need to see her had been compulsive from the moment of arrival. Even though he was quite sure of what was ahead, a vestigial, irremovable romanticism hurried him on. His mind’s eye, incurably bifocal, could never stop searching for the fairy-tale maiden who made his young manhood a time of bewitchment, when springtime was the only season and the days revolved on a lovers’ spectrum of sunlight, twilight, candlelight and dawn.

Next old business I, old business II

Published as The Disenchanted by Budd Schulberg (1950).