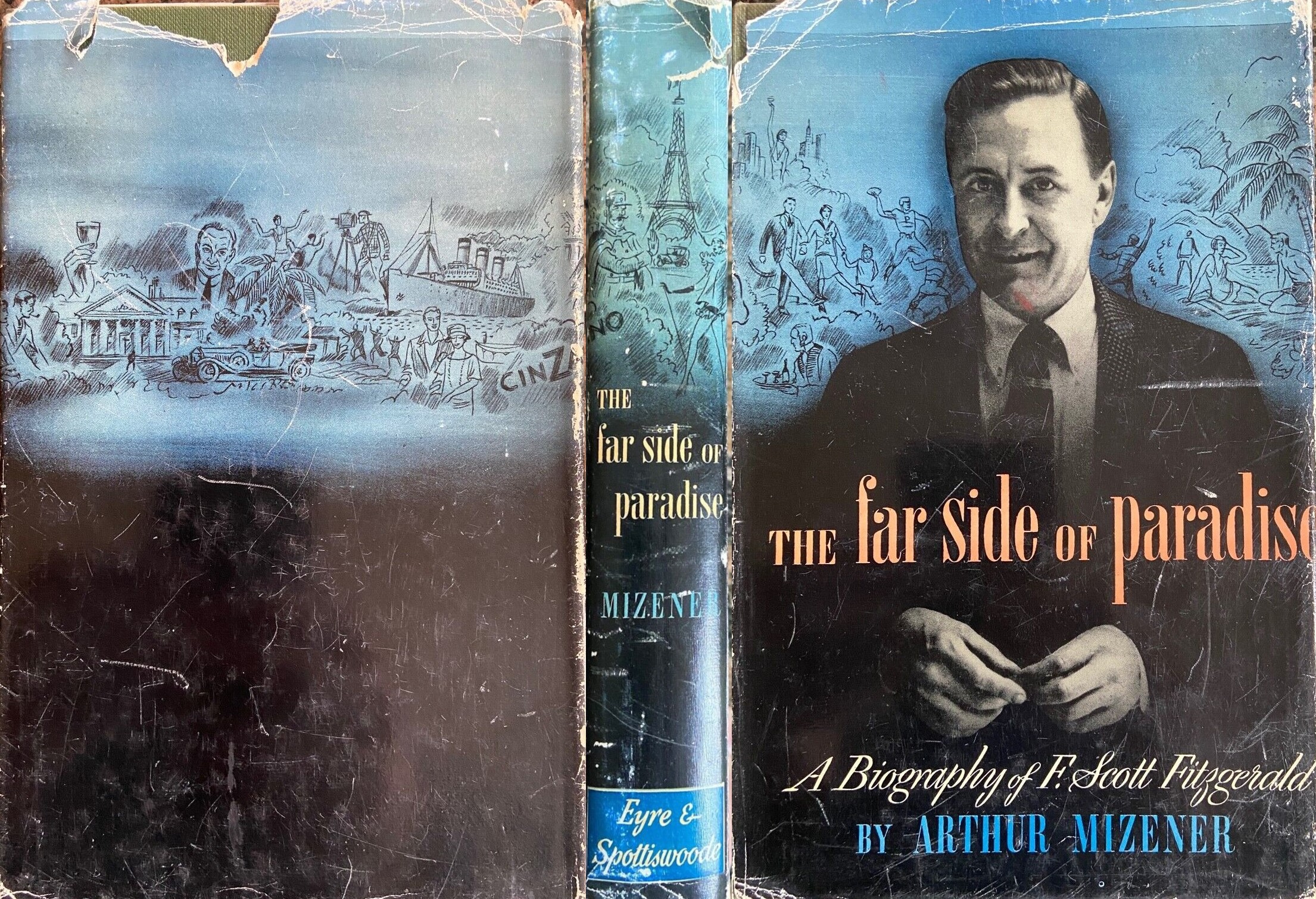

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter XII

All this disappointmentand suffering had their effect on Fitzgerald. His drinking increased, and it made him subject to fits of nervous temper and depression and less capable of providing the regular life Zelda needed. It also affected his work, for in spite of his attempts to persuade himself then, and later, that he could work only with the help of gin, he was as inefficient as most people when he had been drinking. A part of his mind understood what he was doing. “Just when somebody’s taken him up,” he wrote in his Notebooks, “and is making a big fuss over him he pours the soup down his hostess’ back, kisses the serving maid and passes out in the dog kennel. But he’s done it too often. He’s run through about everybody, until there’s no one left.”

Yet in spite of these handicaps, he managed to make a home and a life for the three of them. He was fighting to save Zelda and to save himself, for the two things seemed to him inextricable. His conception of what he was trying to do is reflected in Dick Diver’s struggle, especially when Dick says: “Nicole and I have to go on together. In a way that’s more important than just wanting to go on.” Over and above his love for Zelda and his desire to save her, he had invested too much of his emotional capital in the relation he and Zelda had built together to be anything but an emotional bankrupt if that relation failed. “I should,” said one of the people who knew him best at this time, “have felt he was much more to blame [about Zelda] if he had grown a little bored by, or indifferent to, her tragedy… than if he had grappled with it daily, and failed, as he did. No one could watch that struggle and not be convinced of the reality of his concern and suffering. He was, of course, a man in conflict with two terrible demons,—insanity and drink… but he appeared to be giving blow for blow; there was hope in him and flashes of confidence.”

It was a dogged fight, with many lost battles, a last stand of the Fitzgerald who had believed that “life is something you dominated if you were any good.” In the end he lost both his objectives, and he knew for all his “flashes of confidence” how desperate the battle was. To a friend who wanted to draw Zelda back into the old life he wrote:

… [you] insist on a world which we will willingly let die, in which Zelda can’t live, which damn near ruined us both, which neither you nor any of our more gifted friends are yet sure of surviving; you insisted on its value, as if you were in some way holding a battle front and challenged us to join you. If you could have seen Zelda, as the most typical end-product of that battle during any day from the spring of ‘31 to the spring of ‘32 you would have felt about as much enthusiasm for the battle as a doctor at the end of a day in a dressing station behind a blood[y] battle…. We have a good way of living, basically, for us; we got through a lot and have some way to go; our united front is less a romance than a categorical imperative and when you criticize it in terms of a bum world… [it] seems to negate on purpose both past effort and future hope….

It was a strange life for the fabulous Fitzgeralds to have arrived at, a life so quiet, at least on the surface, that Fitzgerald was able to say in the fall of 1933 that they had “dined out exactly four times in two years.” Because of his awareness of its irony, he was always fond of remembering an occasion about this time when “a young man phoned from a city far off, then from a city near by, then from downtown informing me that he was coming to call, though he had never seen me. He arrived eventually with a great ripping up of garden borders, a four ply rip in a new lawn, a watch pointing accurately and unforgivably at three a.m. But he was prepared to disarm me with the force of his compliment, the intensity of the impulse that had brought him to my door. ‘Here I am at last,’ he said teetering triumphantly. ‘I had to see you. I feel I owe you more than I can say. I feel that you formed my life.’”

There were many good times. Afterwards Fitzgerald treasured the memory of sitting “at La Paix watching thru my iron grill [the bow window of his study was leaded] one of your tribe moving about the garden, & wondering if Zelda had yet thrown the tennis raquet at Mr. Crossby [the tennis coach].” Sometimes he escaped from his prison to join the tennis game with Scottie and Zelda and the Turnbull children. “He played a sensational if somewhat unsteady game,” Andrew Turnbull remembered. “He was best at the net where he could hit the ball hardest and where it had the shortest distance to go. His cry was ‘I’ll perforate you, Andrew!’ which he never did, but his tone of voice always gave you the idea that he was going to do so.”

He loved the children and was always successful with them because he met them quite seriously on their own grounds. He spent hours teaching them to dive, to shoot (with a .22 at Scottie’s dolls); he made up elaborate historical games to be played with the beautiful Greek and Roman lead soldiers they had bought Scottie in France and awarded prizes for the best Roman city built for them on the dining-room table; he wrote a children’s play which was performed at the Turnbulls’ at Christmas; he helped the children build an igloo when there was a rare heavy snow. He did card tricks for them—“though his hands were white and quivering, he did marvels with the cards.” He talked, especially to Andrew, about football (“quantities of this,” Andrew remembered), about courage and how to handle men and how to treat girls.

When T. S. Eliot came to Hopkins in the fall to give the Turnbull lectures, Fitzgerald dined with him at the Turnbulls’ house on the hill and, in a flash of impudent courage, read a section of The Waste Land aloud to Eliot to show how it should be done. He was also full of curiosity about the Communists who were beginning to appear on all sides. He spoke out of his old twenties feeling about war to a liberal group at Hopkins and for a while the house was full of CPers. “The community Communist,” Zelda wrote Perkins, “comes and tells us about a kind of Luna Park Eutopia. … I have taken, somewhat eccentricly at my age, to horseback riding which I do as non-committally as possible so as not to annoy the horse. Also very apologetically since we’ve had so much communism lately that I’m not sure it’s not the horse who should be riding me.” After a good deal of excitement—and one man who camped with them for weeks and weeks—Fitzgerald gave it up. “To bring on the revolution,” he noted, “it may be necessary to work inside the communist party.” His considered feelings about Marxism—at once naive and penetrating—appear in the Brimmer episode in The Last Tycoon.

He also got down at last to steady work on his novel. The evidence suggests that the version of the novel he had projected about 1929 and had got some work done on was now drastically revised again. The minute he got back from Hollywood in January, 1932, he began to replan it, and the undated “Sketch” for Tender Is the Night was probably made at this time.[See Appendix B.] “I am exactly six thousand dollars ahead,” he wrote Perkins in January. “I am replanning [my novel] to include what’s good in what I have, adding 41,000 new words andpublishing. Don’t tell Ernest or anyone—let them think what they want.” That supercilious Hemingway ghost who spent all his time thinking Fitzgerald would never write seriously again was a projection of his own conscience with which he haunted himself; it was one of his sharpest spurs. “Am going on the water wagon from the first of February to the first of April,” he wrote Perkins a little later, “but don’t tell Ernest because he has long convinced himself that I am an incurable alcoholic… I am his alcoholic just like Ring is mine and I do not want to disillusion him, tho’ even Post stories must be done in a state of sobriety.” Like this one, many of Fitzgerald’s fantasies began to get nearer the surface at this time and to threaten to intrude on his daily life. In a moment of anger at Zelda in June he wrote his lawyer to ask about the legal requirements for divorce and in August made—as if from his deathbed—a witnessed statement that “I would like my novel in its unfinished form to be sent to John Peale Bishop… who I appoint as my literary executor in case of misfortune….”

But his book was going so well that in momentary enthusiasm he wired Perkins: think novel can safely be placed on your list for spring. Zelda’s second breakdown ended this hope, but of that August at La Paix he noted later that “the Novel [is] plotted and planned, never more to be permanently interrupted.” In October Zelda was writing that “Scott’s novel is nearing completion. He’s been working like a streak,” and with one of his old outbursts of fun Fitzgerald wrote Perkins: “I now figure this [first installment for serialization in Scribner’s Magazine] can be achieved by about the 25th of October. I will appear in person carrying the manuscript and wearing a spiked helmet…. Please do not have a brass band as I do not care for music.“

But all this time the deadly battle went on. All night long, night after night, the light burned behind the leaded bow window of his study, where Fitzgerald, if he was not working,was fighting his demons and often being defeated; “alone,” as he said, “in the privacy of my faded blue room with my sick cat, the bare February branches waving at the window, an ironic paper weight that says Business is Good, a New England conscience—developed in Minnesota…” There were, said one of his closest friends, three things he loved at this time; they were his work, Zelda and Scottie, drink—in that order. The decline in his morale had increased his hypochondria, so that when he caught intestinal flu and was in the hospital for two weeks in September, he made much of it. Once again he began to suffer from insomnia. Whether he imagined it was worse than it was, as many people thought, or not, he suffered.

… so I get up and walk—he wrote in an essay on insomnia—I walk from my bedroom through the hall to my study, and then back again, and if it’s summer out to my back porch. There is a mist over Baltimore; I cannot count a single steeple. … I could have acted thus, refrained from this, been bold where I was timid, cautious where I was rash.

I need not have hurt her like that.

Nor said this to him.

Nor broken myself trying to break what was unbreakable.

… what if all [after death] was an eternal quivering on the edge of an abyss, with everything base and vicious in oneself urging one forward and the baseness and viciousness of the world just ahead. No choice, no road, no hope—only the endless repetition of the sordid and the semi-tragic…. I am a ghost now as the clock strikes four.

No wonder that, about this time, writing to Edmund Wilson, he headed one of his letters “La Paix (My God!).”

He continued to work hard on his book through December, though he noted that “drinking increased things go not so well.” In February he made a disastrous trip to New York. “I came to New York to get drunk,” he wrote Wilson when he got back, “… and I shouldn’t have looked up you and Ernest in such a humor of impotent desperation. I assume full responsibility for all unpleasantness—with Ernest I seem to have reached a state where when we drink together I half bait, half truckle to him….” (“I talk with the authority of failure,” as he put it elsewhere, “—Ernest with the authority of success. We could never sit across the table again.”)

Throughout the spring and early summer he was in and out of Hopkins with various ailments. He lost his driver’s license. But he was still fighting. During the spring the Vagabond Players put on a piece of Zelda’s called “Scandalabra” and Fitzgerald helped rewrite it, and when a friend did what he called “A Revusical” for the same company, Fitzgerald wrote a lyric for it. He was still working steadily on his book.

Besides writing Zelda was now painting, often in a disturbing vein; there were many crucifixions with faces hauntingly like her own and ballet dancers with enormous, swollen limbs. In the spring of 1934 Cary Ross put on an exhibition of Zelda's work in New York. 'Parfois la folie est la sagesse,' said the motto on the little catalogue. 'The work of a brilliant introvert, they were vividly painted, intensely rhythmic,' said Time (April 9, 1934). She was not improving. “All through the year and a half that we lived in the country…” Fitzgerald wrote later, “there would be episodes of great gravity that seemed to have no ‘build-up,’ outbursts of temper, violence, rashness, etc. that could neither be foreseen or forestalled.” Sometime during this summer she and Fitzgerald sat down, in the presence of a psychiatrist and a secretary, to thrash out their difficulties. The strongest impression the psychiatrist retained from this discussion was of the intimacy of their two natures. At one point, Fitzgerald, trying to convince Zelda that she was “just an old schizophrenic,” instanced an odd act of hers when she had been out riding. She denied the oddity hotly and Fitzgerald said, “Maybe it was a schizophrenic horse,” and Zelda suddenly roared with laughter, saying, “O Scott, that’s really good; that’s priceless.” Fitzgerald laughed, and everybody was for a moment good-humored. They were so close that they moved together from anger to amusement, without pride, as one does in the privacy of his own mind.

But because they were so intimate, their quarrels were destructive. “Family quarrels are bitter things,” said Fitzgerald. “… they’re not like aches or wounds; they’re more like splits in the skin that won’t heal because there’s not enough material.” Under the strain of trying to carry through his program of building up Zelda’s ego by encouraging her writing and painting, Fitzgerald often grew angry at the sacrifice of his own work it entailed. “… my writing was more important than hers by a large margin,” he wrote at one of these times, “because of the years of preparation for it, and the professional experience, and because my writing kept the mare going….” Perhaps this assertion was partly justified; it is remarkable how often people felt, against their better judgments, that Zelda’s view of things was more trustworthy than Scott’s and let themselves be persuaded to accept it. What the doctor Fitzgerald was writing did understand was the way Fitzgerald often sacrificed what meant a great deal to Zelda, not to the legitimate demands of his work, but to his drinking and his nervous irritability. At such times, too, he probably hurt Zelda by allowing her to see his real opinion of her work, an opinion which was influenced by the competitive feeling which had always been a part of their relation. Sometime in 1934 he made a note for a story which runs:

Andrew Fulton, a facile character who can do anything is married to a girl who can’t express herself. She has a growing jealousy of his talents. The night of her musical show for the Junior League [this is Zelda’s Scandalabra] comes and is a great failure. He takes hold and saves the pieces and can’t understand why she hates him for it. She has interested a dealer secretly in her pictures… and plans to make [an] independent living. But the dealer has only been sold on one specimen. When he sees the rest he shakes his head. Andrew in a few minutes turned out something in putty and the dealer perks up and says “That’s what we want.” She is furious.

Nonetheless, it was basically true that their “united front [was] less a romance than a categorical imperative”—for them both. When their session with the psychiatrist was finished the psychiatrist asked the secretary, “Now who do you think ought to be in a sanitarium?” “All three of you,” she said.

Fitzgerald’s mental state contributed to making Zelda’s recovery more difficult. But much of his trouble in dealing with her came from his refusal to admit he could not reason with her; to do so would be to admit that part of himself was gone for good. When she went into her spells of silence and locked herself in the room for whole days at a time, he would slip notes under her door begging her to consider what a bad impression such conduct would make on the doctors. At bottom Zelda’s trouble was something that was happening to them both.

In June Zelda accidentally set La Paix on fire by trying to burn something in a long-disused fireplace. The chimney-caught and before the fire was under control the third floor had been burned out. Fitzgerald entered into the excitement of the occasion with gusto, directing the firemen and serving drinks all around when it was over. But it was a turning point for him. He would never have the house repaired because, he said, he could not endure the noise, and the macabre disorder of the place with its burnt-out and blackened upper story was a kind of symbol of the increased disarray of his own life. His dependence on alcohol for the energy to work had increased and he began to have less control over his tendency to get helplessly drunk; on one occasion he took Andrew Turnbull to Princeton for a football game and Andrew had to find his own way back to Baltimore. Fitzgerald suffered more from such episodes than anyone.

He also had sporadic bursts of anxiety about the effect of his drinking on Perkins and others whose confidence he was dependent on. He therefore made pathetically transparent attempts to pass himself off as a man who went on an occasional bust; he would write Perkins that “I was in New York last week on a terrible bust. I was about to call you up when I completely collapsed and laid in bed for twenty-four hours groaning. Without doubt the boy is getting too old for such tricks.” Nor did he succeed much better with his trick of bribing waiters to fill his tumbler with gin instead of water when he dined out. The pretense that all this was merely a healthy man’s casual dissipation when his hands shook so that he could hardly light a cigarette deceived no one.

About this time a doctor in New York, perhaps hoping to frighten him into facing his situation, told him he would die if he did not stop drinking and put him on an allowance of one gill of gin a day. He gave Fitzgerald a gill measuring glass and Fitzgerald started home with the glass in one pocket and a quart of gin in the other. On the way home he stopped off in Wilmington to see his old friend John Biggs, now a distinguished judge. He was so obviously ill that Judge Biggs took him out to his home in the country. Sitting on the lawn Fitzgerald began to talk, and carefully, gill by gill, finished the quart of gin. As his secretary said, he did not really want to get well.

In spite of illness and alcohol, he got the manuscript of Doctor Diver’s Holiday to Perkins in October. He distrusted a title with the word doctor in it because he thought it might frighten readers off, but he did not think of Tender Is the Night until just before the novel began to run in Scribner’s Magazine, and even then its adoption was delayed because Perkins thought it had no connection with the story. But Perkins was enthusiastic about the book and it was scheduled for serialization in four installments beginning in December. The decision about the title came so late that some of the advertising actually uses Doctor Diver's Holiday and it was so called in Who's Who that year. Before TENDER IS THE NIGHT could be serialized in Scribner's, Fitzgerald had to arrange with Liberty about the agreement he had made with them in 1926 (see above). This arrangement was made in October 1933, and Scribner's then undertook to pay Fitzgerald $10,000 for the serial rights, $6,000 of which was to be applied to his debt to Scribner's (Perkins to Scott Fitzgerald, October 18, 1933). He was pushing Fitzgerald hard for the final revisions, so that Fitzgerald was working very close to the magazine’s deadlines. “The third installment,” Perkins wrote November 10, 1933, “we shall need by December 14. … I hope it willgive you a chance to lay off for a day or two.” This was not tyranny. Perkins knew—for all Fitzgerald’s efforts to deceive him—how easily Fitzgerald could slide from drinking just enough to keep going into a completely unproductive condition. As always, a part of Fitzgerald knew it too, and when the whole nightmare business of revising Tender Is the Night was over he wrote Perkins a shrewd clinical note about the effects of alcohol on composition.

It has been increasingly plain to me that the very excellent organization of a long book or the finest perceptions and judgment in time of revision do not go well with liquor. A short story can be written on a bottle, but for a novel you need mental speed that enables you to keep the whole pattern in your head and ruthlessly sacrifice the sideshows as Ernest did in “A Farewell to Arms.” If a mind is slowed up ever so little it lives in the individual part of a book rather than in a book as a whole; memory is dulled. I would give anything if I hadn’t had to write Part III of “Tender Is the Night” entirely on stimulant. If I had [had] one more crack at it cold sober I believe it might have made a great difference…. Ernest commented on sections that were needlessly included and as an artist he is as near as I know for a final reference.

By now serious financial difficulties were beginning to accumulate for him. With his decline in popularity as the proletarian decade got under way and with his concentration on the writing of Tender Is the Night, he turned out only nine stories in 1932 and 1933—six in the first year and three in the second. As the depression became more serious, the prices for his Post stories began to fall from the old $4000 to $3500 or $3000 and, occasionally, to $2500. His royalties in these years totaled $50. The result was an income less than half what it had been in 1931, and this includes over $5000 in advances on Tender Is the Night. He was even driven toborrowing from his mother, remembering bitterly how he had written her only three years before that “all big men have spent money freely.”

Up to now he had met financial crises by a burst of story-writing or a trip to Hollywood, but he had made a failure of his last trip to Hollywood and he did not have the energy for the stories any more. “… after a good day’s work,” he said about this time, “I am so exhausted that I drag out work on a story to two hours when it should be done in one and go to bed so tired and wrought up, toss around sleepless, and am good for nothing next morning. … to work up a creative mood there is nothing doing until four o’clock in the afternoon. Part of this is because of ill health. … I have drunk too much and that is certainly slowing me up. On the other hand, without drink I do not know whether I could have survived this time.” He could still work all night when he got well started, but he paid a big price for it in spells when he could do nothing. Nor could these financial difficulties be met by economies. His secretary, who tried vainly to put them on a budget, found at the month’s end that there were always large checks to cash which no one could account for. “Their idea of economy,” she remarked, “was to cut the laundress’s wages $2.50.” From this time until he went to Hollywood in 1937 Fitzgerald continued to fall behind financially.

With most of Tender Is the Night off his hands he felt he owed himself a vacation and decided to take Zelda to Bermuda for Christmas. Before they went, they moved from La Paix to a smaller house at 1307 Park Avenue in Baltimore. This move was made partly for financial reasons, partly because Fitzgerald sensed that another period of his life had ended and did not want to stay at La Paix. Before they sailed he had lunch with Wilson in New York and there was a quarrel. Rightly or wrongly Fitzgerald blamed himself for this quarrel, for with the loss of his self-confidence (“Last of real self-confidence,” he noted in February), he was inclined to blame himself for all failures in his personal relations and to feel he could not do anything right, just as, in his old self-confident days, he had found it easy to think he could not do anything wrong. He was still “haunted by [the] Wilson quarrel” a month later. Not until March, when he went out of his way to call on Wilson, was he able “to think that our squabble, or whatever it was, is ironed out” and to cease blaming himself for it. The Bermuda trip was a failure; he was down with pleurisy all the time they were there. They got back in time for their first Christmas at 1307 Park Avenue and Fitzgerald went back to work on the last installment of Tender Is the Night and on the proofs for the book. This work was interrupted abruptly by Zelda’s third breakdown.

Between the after-effects of her previous breakdown and the effort it cost her—and she made a great effort—to keep Fitzgerald going, she had often been near the end of her rope while they were living at La Paix.

We are more alone than ever before while the psychiatres patch up my nervous system—she wrote John Peale Bishop. “This,” they say “is the way you really are—or no, wasn’t it the other way round?”

Then they present you with a piece of bric-a-brac of their own forging which falls to the pavement on your way out of the clinic and luckily smashes to bits, and the patient is glad to be rid of their award.

Don’t ever fall into the hands of brain and nerve specialists unless you are feeling very Faustian.

Scott reads Marx—I read the cosmological philosophers. The brightest moments of our day are when we get them mixed up.

Sometimes, when she was less certain than at others of which way round she really was, this tragic wit became frighteningly bitter. One of their friends remembers being at La Paix for dinner when Zelda came downstairs late. She stood for a perceptible moment in the doorway, a beautiful figure in a lovely evening dress. Then she stepped carefully out of her evening slippers, looked at their guest, and said in a sepulchral voice: “John, aren’t you sorry you weren’t killed in the war?”

In January, as a result of these accumulated pressures, she broke down completely and returned to the sanitarium. Fitzgerald was still trying to help her and whenever he could would take her from the sanitarium for long walks about the Turnbulls’ grounds next door. But one warm spring day, as they were sitting under the trees in what Zelda once called a “nice Mozartian hollow disciplined to elegance by imported shrubbery, of the kind which looks very out of place anywhere,” Zelda, hearing a train approaching on a near-by branch line, leapt up and started to run toward it to throw herself under it. Fitzgerald caught her just short of the embankment as the train passed. With the increase of such dangerous impulses they tried, on the advice of the doctors, a sanitarium in up-state New York. But Zelda only grew worse there and in May had to be brought back to Baltimore in a catatonic state.

For the next six years, except for brief periods of relative stability, she was confined to various hospitals and gradually, along with his other hopes, Fitzgerald began to give up his belief in her eventual recovery. “I left my capacity for hoping,” he said, “on the little roads that led to Zelda’s sanitarium.” Little by little he evolved an attitude which would protect him against the terrible temptation to believe in her reasonableness and to try to persuade her to be well. “Zelda,” he kept telling himself, “is a case, not a person.” For the rest of his life, however, he kept having to fight this battle over again, for the psychological wrench involved in writing off the investment of love and happiness and effort they had both made in their relation was more than he could ever quite manage. “Do you remember,” he wrote, trying as always to preserve the past, with all its enormous investment of feelings, that he would never know again,

Do you remember before keys turned in the locks,

When life was a closeup, and not an occasional letter,

That I hated to swim naked from the rocks

While you liked absolutely nothing better?

Do you remember many hotel bureaus that had

Only three drawers? But the only bother

Was that each of us got holy, then got mad

Trying to give the third one to the other…

And, though the end was desolate and unkind:

To turn the Calendar at June and find December

On the next leaf; still, stupid-got with grief, I find

These are the only quarrels that I can remember.

He knew so well that all this would gradually fade if they were separated. “As you probably know,” he wrote one of the doctors in August, “I saw my wife yesterday and spent an hour and a half with her. It was much better than any of the nine or ten times that I have seen her since she broke down again last January. She seemed in every way like the girl I used to know. But, perhaps for that reason, it seemed to both of us very sad and she cried in my arms and we felt that the summer slipping by was typical of the way life is slipping by for both of us.” Life went on slipping by; they lived in different worlds, until bit by bit the common ground decreased and their letters became more and more sadly impersonal.

But the tragedy, with all its loss and remembrance, was always there for them both, almost too terrible to contemplate steadily. Sometime in 1938 or 1939, after one of their meetings, Zelda wrote:

Dearest and always Dearest Scott:

I am sorry too that there should be nothing to greet you but an empty shell. The thought of the effort you have made over me, the suffering this nothing has cost would be unendurable to any save a completely vacuous mechanism. Had I any feelings they would all be bent in gratitude to you and in sorrow that of all my life there should not even be the smallest relic of the love and beauty that we started with to offer you at the end….

Now that there isn’t any more happiness and home is gone and there isn’t even any past and no emotions but those that were yours where there could be my comfort—it is a shame that we should have met in harshness and coldness where there was once so much tenderness and so many dreams. Your song.

I wish you had a little house with hollyhocks and a sycamore tree and the afternoon sun imbedding itself in a silver tea-pot. Scottie would be running about somewhere in white, in Renoir, and you will be writing books in dozens of volumes. And there will be honey still for tea, though the house should not be in Granchester.

I want you to be happy—if there were any justice you would be happy—maybe you will be anyway.

Oh, Do-Do Do Do—

I love you anyway—even if there isn’t any me or any love or even any life—

I love you.

Nor, though he had another life, as Zelda did not, could Fitzgerald ever relinquish the burden of the past. When Zelda showed signs of increased stability in 1936 he wrote a friend that “there is a chance which I go to sleep hoping for, that she may be out into the world again … by April or May.” And when he came to write The Last Tycoon and to think about his feelings for Zelda in order to conceive Stahr’s feelings for Minna, he found he had to work out the “case” position all over again. “How strange,” he wrote in one of the notes for the book, “to have failed as a social creature—even criminals do not fail that way—they are the law’s Loyal Opposition, so to speak. But the insane are always mere guestson earth, eternal strangers carrying around broken decalogues that they cannot read.” And in a moment of revulsion at this betrayal of the past, he spoke bitterly of “the voices fainter and fainter—How is Zelda, how is Zelda—tell us—how is Zelda” (Notebooks, F). What appears to be a first outline of Stahr's attitude appears in the Notebooks (C): 'Cass thought. 'When I married Jill I didn't want to and I had every reason not to. But afterwards I had eight perfect years - eight perfect years with never a night of going to sleep in anger and never a morning when we didn't think first of each other.' He tried the usual specifics for sorrow - endless work, an expedition into drink, almost everything except women. And he said aloud a few times without striving for effect 'That's over - my heart's in the grave.' ' Not only this note but many passages in 'The Last Kiss' (Collier's, April 16, 1949) and The Last Tycoon, New York, 1941 are too close to the facts - or to Fitzgerald's version of the facts - to leave much doubt of the connection between Stahr's feelings for Minna and Fitzgerald's for Zelda. Though she was ignorant of much of Fitzgerald’s life after 1934, Zelda was substantially right when she wrote, a few days after his death, “Scott was courageous and faithful to myself and Scottie and he was so devoted a friend that I am sure that he will be rewarded; and will be well remembered.”

Through all this, he was struggling with the proofs of Tender Is the Night. Sick—he was more and more in the hospital now for two or three days at a stretch getting himself straightened out—and tired as he was, they seemed to him endless. But he finally fought his way through them and Tender Is the Night was published on April 12, 1934.

Next chapter 13

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).