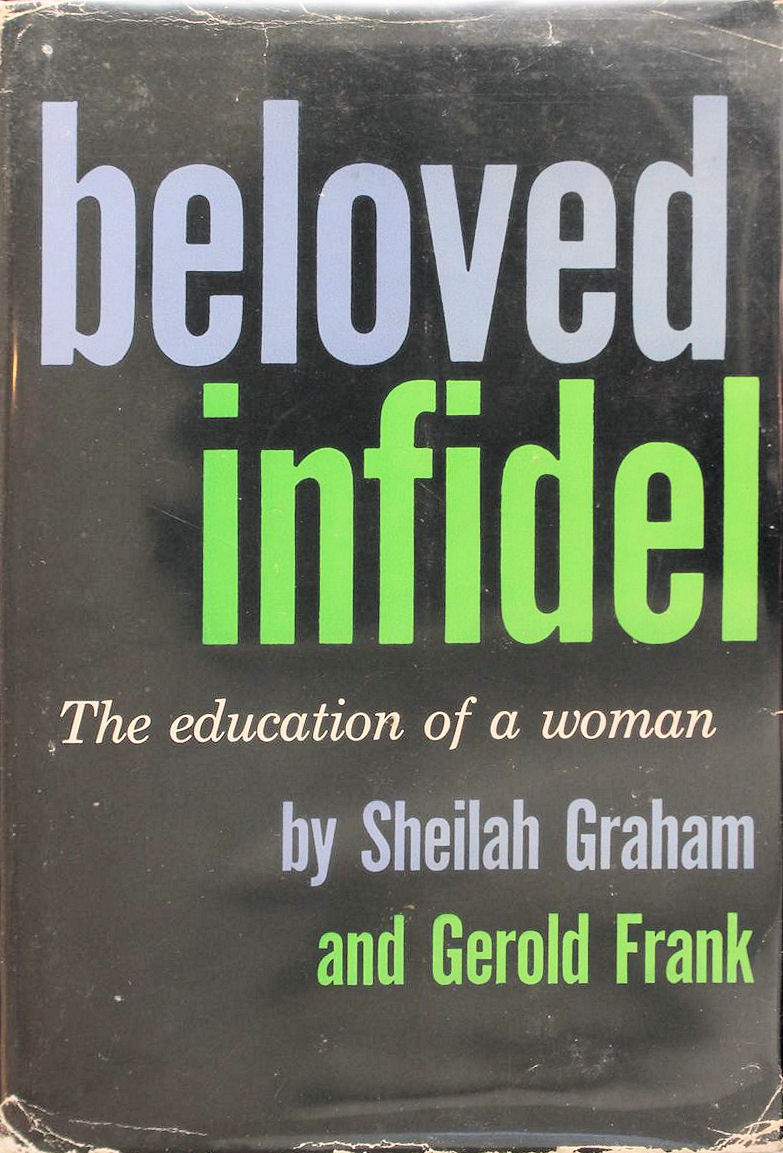

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

A HUGE BOUQUET of American Beauty roses were delivered to my apartment. The card read simply, “Scott.” The flowers were magnificent. It would be a pity to throw them away. I arranged them in a vase.

The next day Frances Kroll called on me with a small suitcase of my belongings—the last of my things from Encino. Scott was working hard, she remarked. He was well though Chapter II of the novel. And he had stopped drinking. When I looked at her she said, “I mean it. It’s true.” “Good for him,” I said indifferendy. We chatted a little longer and then she left.

At Encino Scott waited impatiently for her. “Well?” he asked. Frances smiled. “They’re there, Mr. Fitzgerald,” she reported. “I saw them in a lovely vase on her desk.”

Scott’s face lit up. “I’ve got her!” he said triumphantly. He had, too, although I did not know it.

I had not seen or talked to him for five weeks. He had apologized to John Wheeler in a telegram which my employer forwarded to me:

I SENT YOU THAT WIRE WITH A TEMPERATURE OF 102 DEGREES AND A GOOD DEAL OF LIQUOR ON BOARD. THERE IS NO REASON TO WORRY ABOUT SHEILAH IN CONNECTION WITH THE STUDIOS. WE HAD SOME PERSONAL TROUBLE IN WHICH I BEHAVED VERY VERY BADLY PLEASE CONSIDER THE TELEGRAM AS THE MUMBLINGS OF A MAN WHO WAS FAR FROM BEING HIMSELF.

SCOTT FITZGERALD

I read it with a curious apathy. It all seemed remote to me now. It was pleasant, those first days of 1940, to be free to enjoy aU that Hollywood had to offer—to’ go out again with young men, to be once more a part of the movie colony. My column now appeared in sixty-five newspapers in the United States and Canada, and on occasion even in the London Evening Standard. Johnny, who through the years remained a faithful correspondent, sent me clippmgs when Sheilah Graham’s HOLLYWOOD TODAY appeared there. Early in January, 1940, Look magazine asked to do a picture story on me as the prettiest columnist m Hollywood. The project fell through when I demurred at posing in a bathing suit. “That’s not my type of thing,” I protested. “I’ll pose for you playing tennis—” When nothing developed, I did not feel too badly. I had come far since my Cochran days.

I had a new assurance. It was pleasing to know the admiration of the men I went out with—even to dismay them, sometimes, with my ability to reel off entire stanzas of Andrew Marvell or Robert Herrick, or point out that Keats had borrowed from Boccaccio, or discuss Matthew Arnold’s influence on English prose. To have as literate and talented a writer as Irwin Shaw say, “It’s amazing how well read you are,” was enormously flattering. And it was fun to flirt again, to dine each evening at another restaurant, table-hopping and gratifyingly conspicuous, to dance each evening at different nightclubs…

One Saturday night I joined a group of friends for an evenmg of fun. We had dinner at Lucey’s, went on for dancing and entertainment at Giro’s, the Mocambo, die Coconut Grove. At the end of the evening I was dropped at my apartment. I entered and switched on the light and sank down exhausted on the sofa just as the telephone rang. It was Scott. “I’d very much like to see you, Sheilo,” he said. “May I see you tomorrow?”

For a moment I did not reply. Suddenly, sitting there on the sofa he and I had bought together at Barker’s Bargain Basement, wearing a frothy rose and blue hat he had always admired, I thought, I cannot bear it. Not the dancing nor the dining nor the flirting nor the empty, empty conversation. I want Scott. I don’t want these other men. They are sweet and charming and personable and tremendously successful, but they are not Scott. I don’t care, I have no pride, I want Scott. His voice came again, softly: “Are you there, Sheilo?”

I said, “Yes, Scott. I’m here.” And I added, “Of course you can see me.”

“All right,” he said. “I’ll pick you up early in the morning—nine o’clock. I want to drive somewhere so we can talk.”

At nine the next morning, an astonishingly early hour for him, he called for me. We were both reserved, even formal. I sat silently beside him as his Httle car slowly climbed the winding, curving road to the top of Laurel Canyon, high above the city. At this early hour on a January Sunday morning, it was utterly silent. There was a lonely, dreary quality to the hills about us and the cold blue sky overhead.

We left the car and I walked with him to the rim of a small knoll. We sat down on the grass, on the edge of the Canyon. Far in the distance gUnted the thin silver line of the Pacific; a little nearer the Malibu mountains, blue and smoky in the morning haze, and here and there on the hills between, patches of purple bougainvillaea. Far below to the left the roofs and spires of Los Angeles lay spread out before us like a painting.

Scott began to talk, slowly. He spoke about himself, about Zelda, about his drinking—he knew he could not drink. He knew that when he was drunk he was unfit for human association. He had begun drinking, as a young man, because in those days everyone drank. “Zelda and I drank with them. I was able to drink and enjoy it. I thought all I needed anywhere in the world to make a living was pencil and paper. Then I found I needed liquor too. I needed it to write.” The day came when he realized he was drinking to escape—not only to escape the growing sense of his wasted potentialities but also to dull the guilt he felt over Zelda. “I feel that I am responsible for what happened to her. I could no longer bear what became of her. I could not bear what had become of me. But liquor did not help me forget. In these past years the escape has been more awful than the reality.” He was finished with this form of escape. He felt stronger, now, than he had felt in a long time, though he still had his T.B. and insomnia to contend with. He looked forward hopefully to the future. He had hired another agent who might find screenwriting jobs for him. He had gotten well into his novel. He knew he could write a good book. He wanted me back, very, very much. “I am going to stop drinking, Sheilah. I have made a promise to myself. Whether you come back to me or not, I will stop drinking. But I want you back—very much.”

He becafiie silent. We were utterly alone in a remote, isolated world of our own. Scott had uttered his last words with such solemnity. I thought, he has never unburdened himself like this before; he has never opened himself like this to me before; he has never before promised he would stop drinking. This might have been an enormous church and I, here, with Scott in a confessional… For a moment I almost shivered. I knew I would take him back but I had to be sure.

“Scott—” I began. I searched for the words. “How do I know I can believe you? Can you stop drinking, Scott? Do you really mean it?”

“I mean it,” he said. There was a long pause. We looked at each other. “Don’t just take my words, Sheilah. Test me.”

I went back to him, and everything fell into place once more.

Scott did not drink. Early in 1940, for the first time in months, he worked on a script again, adapting his short story, “Babylon Revisited,” which Producer Lester Cowan bought from him for a thousand dollars. Cowan paid him an additional five thousand dollars to turn it into a screen play. One thousand dollars was a ridiculously low price for an F. Scott Fitzgerald movie property; five thousand dollars for the sixteen weeks he was to spend on the script was also far below Scott’s rate of payment. But he was grateful for the opportunity. Once more he was gainfully employed, he enjoyed working on his own story, and his morale was high.

We lived very quietly in Encino, now. At noon each day, when I had finished my column, Scott would come down to the pool and give me swimming lessons. While I floundered in the water, Scott, in a sweater and hat, coached me from the side, careful to keep out of the sun no matter how exasperated he grew. After lunch, we each went to our own rooms. Scott to work on the script, I to read steadily whatever book he had assigned me. I was deep in Renan’s The Life of Jesus; at the same time Scott had me read the Gospels of St. Mark and St. Luke; then I began Calverton’s The Making of Society. After dinner we took long walks and Scott discussed with me in detail what I had read. Or, in the evening, we sat like an old married couple on his balcony, sometimes not exchanging a word for a long tune. Somewhere in the vicinity but out of sight was an RKO Western lot and in the hush of the Encino night, broken only by the singing of crickets, we would suddenly hear a distant voice: “Ev’ry-body-quiet! Camera—shoot!” And then the thunder of horses’ hoofs and the crack of guns in the night air. It was strange, weirdly theatrical—and we were content.

Once we drove down to Tijuana for a day and, on impulse, had a picture snapped of us by a sidewalk photographer. I sat beaming on a sleepy burro and Scott, in a sombrero and with a colorful serape tossed over one shoulder, stood beside me, every inch the cabellero. It was the only photograph we had ever had taken together.

Because Encino, warm as it was in winter, became insufferable during the summer, in April Scott gave up his house. I found him an apartment in Hollywood on the street next to mine. To economize, we shared the same maid, each paying half of her salary. We dined at each other’s apartment on alternate nights: one night she cooked his dinner and I was his guest, the next, she cooked mine and he was my guest. Again, like a married couple, we went shopping at night in the supermarkets on Sunset Boulevard, or spent an hour in Schwab’s drugstore, five minutes away, browsing among the magazines and ending our visit sipping chocolate malted milks at the ice-cream counter. On the way home we chanted poetry to each other, swinging hands as we walked in the darkness, Scott declaiming passionately from Keats:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both. In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

And I would reply with equal fervor:

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Sometimes a passerby stared at us and I would burst out laughing, but Scott would maintain a stern demeanor.

Could either of us have known, this summer of 1940, that Scott was in the last year of his life? There were no signs. In fact, everything underlined his own hopeful words—he had become a new man. He was not drinking; and now that he was not, I marveled at how much work he accomplished. He worked on his script, on his novel, on short stories for Esquire; at the same time he wrote endless letters to his daughter, his editors, his friends, dramatically describing his nightsweats and temperature.

He found time to follow every detail of the war in Europe on a map in his study, working out his own ideas of military strategy on paper, as he used to plot football plays on the backs of the U.C.L.A. programs. On May 31, we were on a train bound for a two-week vacation at San Francisco and the World’s Fair when news came of the British evacuation from Dunkirk. Scott almost did a jig in the aisle as Anthony Eden’s voice came over the club-car radio announcing the rescue of three-fourths of the British Army. Until then, despite my outraged arguments, Scott had predicted Britain’s defeat. “Scott, you don’t know the British!” I’d say hotly, and he would reply, “Oh, Sheilah, they can’t possibly win.” Now, he said jubilantly, “You’re going to win! You’ve saved your soldiers to fight another day!”

The fall of France was reported on our return to Los Angeles. It threw Scott into mourning but overnight his natural buoyance reasserted itself and he came hurrying into my flat with a long poem he had just written. “Here,” he said, “you’re always complaining history con-; you. Memorize this and it will fix French history— .: cast the highlights—in your mind for good.” There was a mischievous gleam in his eye as he gave it to me. Among the verses were these:

LEST WE FORGET

(France by Big Shots)

Frankish Period 500-1000

Clovis—baptized “en regnant”— Was ancester to “rois faineantes”

Hammer! Hammer! Charles Martel! At Tours he sent the Moors to Hell Mayor-of-the-Palace, Boss of the Gang He cleared the way for Charlemagne

Charlemagne stands all alone

One pine in a burned-over zone.

He passed—and Europe should cry “Merde!” on

The fatal treaty signed at Verdun. . .

The House of Valois 1350-1600

For Charles the Wise and Charles the Mad And Jehan’s Charles the times were bad; But Jehan and the Bastard met And glued that dome on Charles-le-sept

Life was no heaven seventh For foes of Louis Eleventh With marriage, guile and hate Created he The State

The Renaissance—France sings and dances Fights and fails with handsome Francis

Catherine de Medici In fifteen hundred seventy-three With her sons (two lousy snots) Massacred the Hugenots. . .

The Revolution

Mirabeau the swell began it Then Citoyan Marat ran it

Hey! Hey!

Charlotte Corday

They didn’t let Danton rant on.

Robespierre was a sea-green incorruptible

They broke his jaw to prove he was intemiptible. . .

The Nineteenth Century

The Consulate and Empire blaze:

And’freeze at last at Borodino Then Elba and The Hundred Days

And Waterloo—and St. Helena

The Monarchs of The Restoration Were not favorites of the nation But even more did Fat Cats hate The Barricades of Forty-eight

Republic Two was soon to falter . . The Decor, now by Winterhalter, Starred Napoleon the Little Bluff—a bushel, brains—a tittle

The Prussians take Sedan and Metz The commune dies on bayonets The Third Republic comes to stay —or rather ended yesterday.

VIVE LA FRANCE!

This was our happiest time. My books were piling up by the score now; Scott appeared with a tape measure and carefully measured my walls for bookcases. When they came, covering one entire wall, we spent several days cataloguing the volumes which once more included his own first editions. (He had replaced them, a little ruefully, inscribing each to me as he had inscribed them before.) Scott sat cross-legged on the floor arranging and checking the books so that fiction and non-fiction, American authors (headed by Dreiser, whom he considered his greatest contemporary) and foreign authors, all had their place. Now and then, in the middle of the day, he would grow tired and have to rest from whatever he was doing, but nothing stopped the eagerness of his mind. Even Cowan’s decision at this time not to use his screenplay of Babylon Revisited was not the crushing blow it would have been six months before. Instead, he asked his agent to see what other jobs were available and devoted more time to his novel. He was full of projects for me. I must start making notes for my autobiography, he told me. “Your story is fascinating, Sheilah,” he said. “Some day you must do it. It should be a book.”

“Oh, Scott,” I’d say. “You should do it—I wish you’d write my story.”

“No,” he would say. “That will be your project. But I’ll help you. I’ll show you how to start.” He brought home a huge leather-bound ledger, the kind used by accountants, that must have cost him twenty dollars. “You must begin by making notes. You may have to make notes for years.” He drew up a rough outline, dividing my life into seven parts: the orphanage, my strolling at night on Piccadilly; my dilemma in choosing between Johnny and Monte; my stage career; my society career; journalism in New York; and Hollywood. “When you think of something, when you recall something, put it where it belongs,” he said. “Put it down when you think of it. You may never recapture it quite as vividly the second time.’*

I had put an iron door between my past and myself. I had opened it only once—when I revealed the truth about myself to Scott. Now, with his encouragement, I began to revisit my childhood. I began to remember smells—the musty horsehair odor of my mother’s flat, the fragrance of Ginger’s hair pomade, Monte Collins’ talc. I began to remember how I felt the first time I sat opposite Johnny at his desk, licking envelopes; I recalled the golden haze at the Pavilion. “That’s good,” said Scott. “Put it down.” And he kept after me. “Make notes, always make notes.” I had noticed, proudly, that some of my observations were in his notebooks. Once, sitting on the balcony at Encino, in the dark, I had said, “The Ping-pong balls on the grass look like stars.” He put it down. One night when the rain drummed on the roof, I said, “It sounds Hke horses weeing.” Scott liked that, and into his notebook it had gone.

Though I jotted down notes whenever I thought of them, I did not neglect my education. I had moved into Scott’s music course. Scott made a present to me of a record player and then, admitting that his knowledge of music was limited, called in Frances Kroll’s brother to help plan the curriculum. Now Scott brought me albums of records instead of books. I was to play each record repeatedly until I was thoroughly familiar with the music. I began to realize that what I had always thought of as great, blaring batches of sound had a tune, a melody, a pattern, hidden in them. We both listened, we read the biographies ot the composers, and we studied music criticism recommended by Herman Kroll. My apartment was filled with music.

Then we took up art. We spent each Saturday afternoon at a gallery or museum. Under Scott’s watchful eye I learned how to look at pictures, to see what Goya and Brueghel and Paul Klee, were aU about. The Huntington Library in Pasadena had outstanding canvases by England’s great painters: portraits by Gainsborough, Reynolds, and Romney, breath-taking landscapes by Constable and Turner. We would pause before each picture and ask ourselves what the artist intended, then check our interpretations with those in the best books of art criticism we could find.

One August day as we strolled through the Huntington Library I said to Scott, half-teasingly, “How well has the best and worst student in the Fitzgerald College of One done so far?”

“Very well, Sheilo,” he said. “I’m quite proud of you— you’ve worked hard.”

“Do you think I’U be ready to graduate soon?”

“Well, let’s see,” he said, seriously. “You’ve been studying about a year and a half. Now, if you were going to Vassar, like Scottie, it would take you four years. But ours is a very concentrated cirriculum—” At this rate, he said, I should be ready to graduate next June. I should consider myself a member of the Class of 1941.

“And you’ll really give me a diploma?”

He laughed. “In your cap and gown. I promise.” I would have to pass a complete written final examination. He would arrange it all. We would conduct appropriate graduation exercises and he would present a hand-lettered diploma, the only one of its kind, to me.

So we planned it.

Next chapter 27

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).