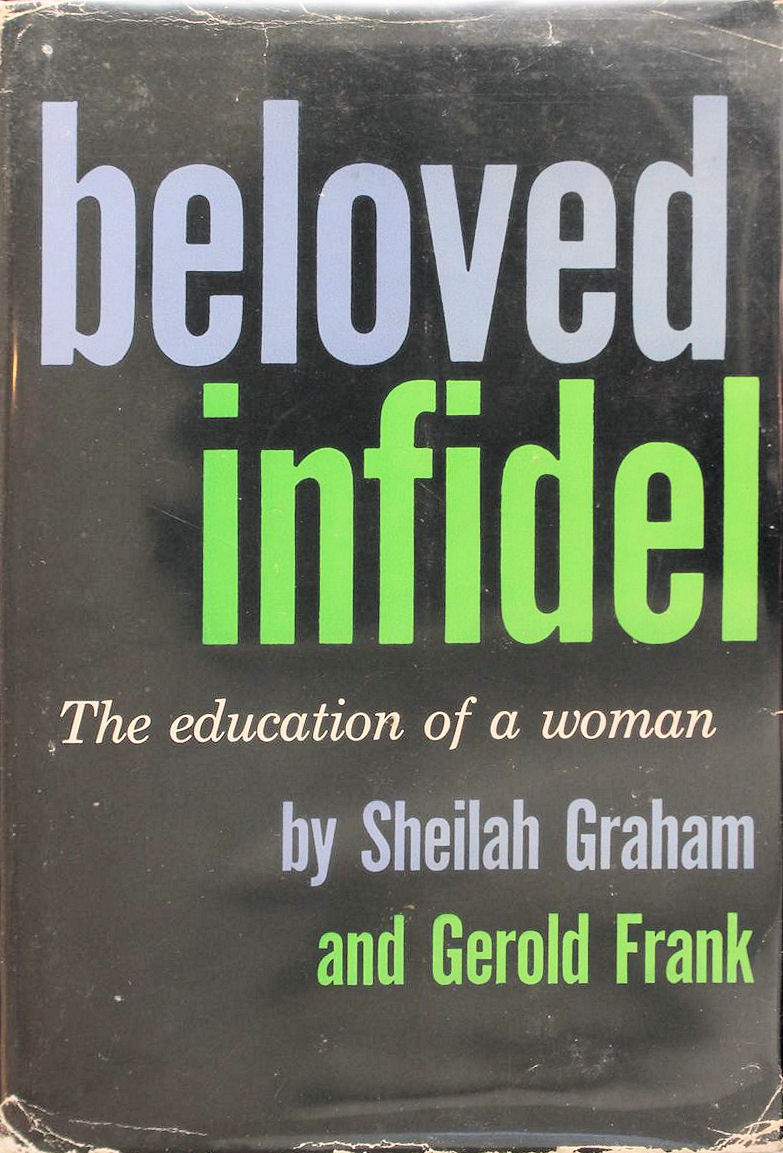

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

At Encino, in the San Fernando Valley, Edward Everett Horton, the actor, had an estate called “Belly Acres.” Here, in spite of Scott’s dismay—”How can I tell anyone I live in ‘Belly Acres’?” he had asked, outraged—I rented a house when Scott’s Malibu lease expired. Malibu was too cold and damp for him in winter: the Valley was always some ten degrees warmer than the rest of the countryside. In addition, the new house was well suited to our needs. Nearby were woods of fir and birch; there was a rolling green lawn, a lovely garden of pink and yellow roses surrounded by a small white picket fence, huge magnolia trees with deckchairs in their shade, a swimming pool and tennis court. The house, one of three on Mr. Horton’s estate, was a big rambling structure with a long balcony off Scott’s bedroom on which he could pace to his heart’s content.

At the beginning Scott was not particularly enamored of the place. Then Buff Cobb dropped in. He showed her around. “Don’t you think this is a rather uninspired house?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” said Buff. “The garden is lovely—”

“Yes,” said Scott, grudgingly. “The garden is kind of charming.”

Buff went on, “And all those little pickets look like little gravestones in a Confederate graveyard.”

Scott looked at her absolutely delighted. “Sheilah!” He ran inside. “She’s made the place livable! We’ve got romance in the house.” Now he was quite happy with it. He suggested that since it was large enough for both of us, I might as well give up my house and take a small apartment in town. I did so, renting a two-bedroom flat off Sunset Boulevard where Scott could work and stay when in town.

Scott helped me choose the furniture. Like newly-weds, we spent an entire morning wandering happily through Barker’s Bargain Basement in Los Angeles inspecting carpets, desks, lamps: among the major pieces we selected were a green chintz sofa and a large green armchair, which Scott, with great seriousness, bounced in several times to see if it were comfortable.

In early January, 1939, David Selznick suddenly called Scott in to work on Gone With the Wind. For a week Scott toiled over the famous staircase scene, asking himself aloud, “What would she say to him? What would he say to her?” I became Scarlett O’Hara; he, Rhett Butler. I struck a pose at the top of our winding staircase at Encino, daintily holding the hem of an invisible evening gown. Scott, standing at the foot of the staircase, called out directions. “Now, slowly—keep your eye on me—”

Slowly, my head high, my skirts lifted from the stairs, I began to descend. From below, Scott looked up at me and smiled—the self-assured, half-provocative, half-disdainful smile of a great lover.

“Miss O’Hara—” he began silkily. I continued to descend, languidly waving an imaginary fan. “Captain Butler, I believe—”

Scott couldn’t contain himself. He burst into laughter.

I ran down the stairs into his arms. We were both laughing. “Am I really such an awful actress?” I asked. “I tried to help—”

He said, “SheUah, it might be better if I work it out on paper.”

But though he was determined to lick the script where others had failed—Selznick had repeatedly brought in new writers on his gigantic project—Scott lasted but two weeks. Suddenly he was dismissed; Director George Cukor was no longer on the picture; and Selznick was casting about for another writer and another director. On the heels of this, Metro faUed to renew Scott’s contract, so that Gone With the Wind turned out to be Scott’s final job for the studio that had brought him to Hollywood eighteen months before.

For the first time since he came west, he was without salary. “Well,” he said hopefully, “I’ll just have to work from picture to picture. Maybe I’U go ahead with my novel. Try some short stories, too.”

It was now that Walter Wanger, the producer, learning that Scott was free, hired Mm to work with Budd Schulberg, a young screen writer, on a film about Dartmouth College’s Winter Ice Carnival, held annually in Hanover, New Hampshire. Wanger was a Dartmouth alumnus and Budd had graduated from Dartmouth a few years before. If the idea of collaborating with a be-ginnmg writer—one who admired him but did not conceal the fact that he thought he had died long ago—was a blow to Scott’s ego, he did not show it. He liked young writers and he welcomed Schulberg cordially.

For days I watched Scott labor on the script with Budd. As always with a new project, he was full of enthusiasm: he worked to instill warmth and charm into this story of a college week end. Here were all the ingredients he had handled so superbly in the past. Yet I could not help thinking—how much hinged on his success here! If he failed on this assignment, too, where would his next job come from? Scott must have felt this concern: in the quiet of the Encino night I heard his endless pacing, back and forth. Sometimes sleep did not come to him untU dawn. When he woke, his face was gray as clay. One morning he said in a matter-of-fact voice, “My T.B.’s flared up.” He was running a low fever which gave him night sweats. It was sometimes necessary, I learned, to change his bed sheets two and three times during the night.

I was alarmed. Despite his annoyance I took his temperature. It was 101 degrees. “Don’t worry about me,” he said irritably. “I won’t be babied. Forget it.”

At this critical stage Wanger, who was in the East preparing to shoot the script, wired Scott and Budd to join him at once in Hanover. I protested to Scott. He was in no condition to fly to New York. “Not with a temperature—”

He said, reluctantly, he must go. He had to carry this project through. All right, I said finally. But if he went, I’d go with him. I had not been to New York for a long time. “It will be a change to write my column from the East for a week or two.” Jonah Ruddy would cover for me here.

In our plane, Budd and Scott were busily discussing their script when I went to my berth. Next morning Scott had the grayness of death on him. I attributed this to a combination of temperature and insomnia. Only then I learned that Budd’s father, B. P. Schulberg, a former producer, had presented Budd with a magnum of champagne before the flight. Scott had been up all night reminiscing with Budd, the two sustaining themselves on champagne. I was furious with them but there was nothing to do.

When we reached New York they dropped me off at the Weylm Hotel, met Wanger at the Waldorf, and went on by train to Hanover. They would be back in a week, Scott said. “Better not call me there. I’ll be working. I’ll phone you.”

The call that came to me from Scott a few days later alarmed me. He was at the Hanover Inn with Budd: they were making wonderful progress. He bubbled over, he was uproariously funny—I knew then that he was still drinking. Liquor plus his illness— anything could happen. “Be back in town Friday,” he said expansively over the phone. “I’ll call you.”

The second call never came. Nor was Scott back on Friday. I waited in my room at the Weylin, growing more frantic as my imagination conjured up every possible tragedy. Saturday came, then Sunday. I put in a call for Scott at the Hanover Inn. Mr. Fitzgerald and Mr. Schulberg had checked out days ago. I telephoned every hotel in the vicinity without success.

On Monday evening the telephone rang. I leaped at it. It was Budd. “What happened?” I demanded. “Where’s Scott?”

Budd’s voice was shaky. “I’ve got bad news, Sheilah—”

“Scott’s dead!” I cried.

“No, no, no. But he’s sick. I’ve been taking care of him. He went on a terrible bender—” Budd began to blame himself. “I should never have given him that champagne.” Scott had been drinking for days, he had made a spectacle of himself at Dartmouth, he’d gotten into an argument with Wanger, Wanger had ordered them both out of Hanover, “it was a sorry, awful mess—”

I broke in. “Where’s Scott now?”

“I can’t tell you,” Budd said evasively. “He made me promise not to. I’m just to say that you’ll see him very soon. I’m sorry I can’t tell you more, Sheilah.” He hung up.

I sat at the telephone. Poor Scott! I blamed Budd for the champagne but I blamed myself for not insisting that Scott remain in Hollywood. What would this do to him?

The telephone rang again. “Hello, Sheilo—” It was Scott. He had checked in at the Weylin a few minutes ago. I hurried down to his room. He was slumped in a chair, unshaven, exhausted, his face with the ashen pallor that terrified me. He had had “the most awful time” in Hanover. “I was never so cold before.” He was running a temperature of 102 degrees, he said, when he had to join Wanger and Budd as they climbed a snow-covered hill leading to a ski jump. “It was agony, Sheilah. I plowed through that snow thinking I’d die.” Every step had been a stab of pain. He made a grimace. “I shouldn’t have left Hollywood. But I needed the money.” It was the first time Scott had admitted his financial difficulties.

“Get into bed, Scott,” I said gently. “I’ll call a doctor and nurse—”

He began to push himself out of the chair. “Must have something to drink,” he said. “Got to have a bottle.”

“Just get into bed, Scott,” I said. “I’ll run out and get you a bottle.”

I went to the bed to turn back the covers—and Scott scuttled out the door and down the service stairs. “Scott, Scott!”—I shouted after him. But he was gone. Almost distraught, I found my way back to my room. How would I get him in condition to return to the coast? I telephoned a physician who had treated me when I lived in New York. “You need a psychiatrist to handle this,” he said. He recommended Dr. Richard H. Hoffman.

Scott had not yet returned when Dr. Hoffman, a soft-spoken man with piercing dark eyes and great charm, arrived in response to my telephone call. He listened while I told him about Scott. Then, with a smile, he said, “I know Mr. Fitzgerald and admire him very much.” He had met Scott and Zelda in Paris in 1925, and had often come upon them at parties given there by mutual friends. “Then you know about his drinking?” I asked. Dr. Hoffman nodded. He had followed Scott’s career through the years. He would do his best to help him.

At this moment, Scott, bottle in hand, came in unsteadily. I introduced them, a little apprehensive because I knew how Scott resented interference. “This is Dr. Hoffman,” I said. “He is a psychiatrist and you met h im before, in Paris, years ago—”

Scott, with exaggerated politeness, took Dr. Hoffman’s hand. “Yes, of course,” he said. It was obvious he did not remember. He looked at him impishly. “A psychiatrist, eh?” He indicated a chair and slid into one himself. “Sit down, Doctor.” He unscrewed the top of his bottle, put his head back and took a long drink, replaced the cover and stuffed the bottle into his pocket. “Now, what is it you’d Hke to know about me?”

I excused myself and left the room.

That night Dr. Hoffman moved Scott to Doctors Hospital and placed him on a strict regimen. He visited him daily; at the end of a week Scott was back at the Weylin where I cared for him. Dr. Hoffman continued his daily treatment.

At the end of two weeks we returned to Hollywood.

I had not talked to Dr. Hoffman alone since our first meeting. That I must not discuss him with the psychiatrist outside his hearing became almost an obsession with Scott. “Anything Dr. Hoffman has to say about me, I want to know,” he said. “There’ll be no whispering in corners.” He pledged me on my word of honor. It was as though Scott feared Dr. Hoffman might reveal something to me that would make me pity him: and this he could not bear.

Not until many years later did Dr. Hoffman, at my request, tell me what he had found about Scott, and what he had told him in their many sessions. Scott, he discovered, suffered from hyperinsulinism, a rapid burning away of body sugars, which might be described as the reverse of diabetes. This condition, although it might have been created by his drinking, now contributed to his need for alcohol. Scott was sugar starved, and alcohol was one of the quickest ways the body could replenish sugar. I thought, this explained his craving for Coca-Cola, his heavily sweetened coffee, his addiction to fudge.

Dr. Hoffman had treated Scott with medication and made use of psychotherapy—spending an hour a day helping Scott analyze his attitude toward himself and his future. Scott, Dr. Hoffman said, was then in despair. He believed he was finished as a writer. “I don’t have it any more,” he told the psychiatrist. “It’s gone, vanished,” Dr. Hoffman said to him, “This is not your death, it is the death of your youth. This is a transitional period, not an end. You will lie fallow for a while, then you will go on.” He quoted Emerson to him: “ ‘On the debris of your despair, you build your character.’ Not on your despair alone. First you destroy your despair, and on its debris you begin to rebuild.” Later, when Scott wrote him, asking for a bill. Dr. Hoffman waived the fee and, in his letter, replied, “Let’s buy a wreath for the grave of your adolescence, and then go on from there.”

But none of this I knew as Scott and I flew back to Hollywood, Scott wan but outwardly cheerful, I wondering, when will this end?

Next chapter 24

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).