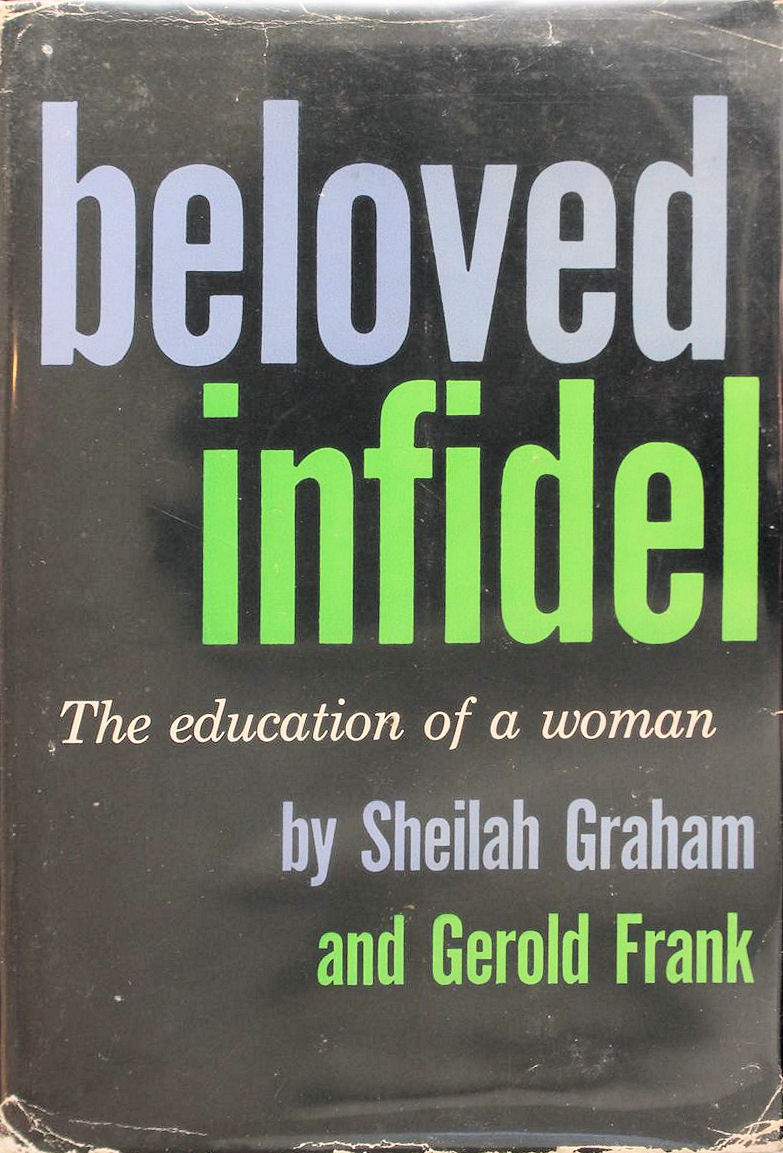

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

A LETTER to me from Scottie:

… waited until we were safely on the Atlantic to tell you how much I love the sweater. It’s so marvelously soft and really I just adore it because I love nice sweaters more than anything in the world…

I thought, she is only sixteen but already she has her father’s gift of making you believe you are the most thoughtful, perceptive person.

… Let me congratulate you on doing such a good job on Daddy—you are definitely a good influence. I hope he isn’t going to get so upset every time I do anything wrong… Anyhow thank you so much for all your trouble.

Love, Scottie.

Scottie had come on her second visit to Hollywood to stay briefly with her father before going on a conducted tour of Europe this summer of 1938. The tour had been Scott’s idea. “War is coming—I’m sure of it,” Scott had told me. “I want her to see Europe as it is, and while she can.”

His daughter’s arrival with Peaches, a schoolmate, posed a problem. Scott, a little unhappily, broached the subject to me a few days before they came. “I hope you won’t feel hurt, Sheilo, but I don’t think it would be good for Scottie to know that you’re staying here.” Would I remove my clothes and my belongings from the beach house for the duration of his daughter’s visit?

It was as though he had shut a door in my face, but I complied, thinking, he’s like a little boy who believes that if he pretends he doesn’t see a thing, no one else sees it. Yet I had noticed a straitlaced, almost puritanical streak in Scott which suq^rised me because it was so contrary to the picture I had gotten of him as daring, nonconforming, and unconventional. He had been shocked when I spoke so casually to him of other men I had known. At parties he was acutely uncomfortable if anyone told a suggestive story: his face froze and he invariably walked away. He winced each time I forgot myself and used any of the colorful language I had picked up from my friends in the British aristocracy, or from the chorus girls backstage at the Pavilion. I finally eliminated even “damn” from my vocabulary. Sometimes he sounded like a disapproving schoolmaster. Once, we were watching a film. One of the characters said, “That stinks!” Scott moved in his seat. When he heard the word a second time, he all but got up and walked out. He hated the word. “It’s offensive,” he would say. The word “lousy” also made him uncomfortable.

Now, when Scottie arrived, although my week-end clothes, my make-up case, my possessions, were nowhere in evidence, she knew. She had only to see us together. I would catch her watching me with those clear blue eyes, Scott’s eyes, trying to make up her mind whether she liked the situation. When I realized, after the second or third day, that she had decided, and in my favor, I was enormously reUeved. I liked her and wanted her to like me.

Scott, as usual, was difficult and short-tempered with her. He was annoyed because for a lark one week end she and another girl had thumbed a ride to a Yale dance in New Haven instead of taking the train. He referred to it again and again until I interceded for her, even daring to tell him, “Now, Scott, you stop picking on her. What she did was perfectly harmless. Let her alone.” He took it from me, grumpily, but he took it.

Still, if he harassed her, there were times when he was the ideal father. One evening she came to him with a problem. Two boys from the East who bored her almost to tears were calling on Peaches and her the next night. She had no idea how to entertain them. Scott used this as a springboard for a little lecture. “Scottie,” he said, “You must have a plan. I’ll give you one. Go out and buy a dozen of the latest dance records. When dancing wears off, remember—action creates conversation. Take them into the kitchen and make fudge. You’ll be so busy mixing, buttering pans, talking about what you’re doing, that no one will be bored. If you’re still stuck after that”— Scott was all but rubbing his hands in delight at his own resourcefulness—”bring them to me. I’ll show them my pictorial history of the war. It fascinates everyone.” There was a gleam in his eye and I knew what it meant. Scott’s book contained gruesome photographs of soldiers with half their faces shot away. He delighted in shocking visitors with it.’

Scottie listened attentively to his advice. Then her face clouded. “My God!” she exclaimed, at that moment sounding exactly like her father. “If they have a good time they’ll want to come again.” Scott threw up his hands.

The sweater I had bought for her trip was the first present I gave Scottie. I enjoyed doing this. Had I a family I would have showered them with gifts. Scott refused to accept anything from me except on Christmas or his birthday, so I bought presents for his daughter on the flimsiest excuse. Scott and Scottie—and in far-off London, Johnny—were as much of a family as I would ever have, I thought.

Scottie had no sooner left than we entertained other guests. All during that summer of 1938 Scott’s friends were in and out. They included Harold Ober, his New York literary agent, to whom Scott, as I learned later, owed considerable money; Cameron Rogers, a screenwriter, and his wife, Buff Cobb, daughter of Irvin S. Cobb, the humorist—both friends of long standing; and Charles Marquis Warren, a brilliant young writer from Baltimore whom Scott considered his protege, Charlie, who was 22, worshipped Scott and invariably addressed him—to Scott’s annoyance—as “sir.” He came often to lunch and later the two men would talk shop while I put on my bathing suit and prepared for a dip. Each time I passed by, Charlie followed me with his eyes. And each time Scott would say irritably, “Charlie, look at me when you talk to me, dammit!” Once Charlie sighed: “God, sir, isn’t she beautiful!” Scott stopped in the middle of a sentence and glowered at him. “Look, you’re bigger than I am, but I can take you—”

Later, after Charlie left, Scott turned to me. “Why does he ‘sir’ me? How old does he think I am?”

Cameron Rogers, his wife Buff, and Scott were engaged in animated conversation. Scott, leaning forward eagerly, was expounding on the Thirty Years’ War. Buff was saying, “I don’t think you can understand Wallenstein unless you consider Richelieu who helped mold him.” Cameron nodded. I had never heard of Wallenstein, Richelieu, or the Thirty Years’ War. Now Scott was deep in the subject, occasionally turning to smile at me to show me that I was included.

I thought, suddenly, I will not be in this position again. They discuss Franz Kafka and T. S. Eloit and Wallenstein and Richelieu and the Thirty Years’ War and I sit on the outside, looking in. If I want to stay in the same world as these people I must do something about it. Eddie Mayer had once told me that Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past was one of the most fascinating and instructive books he had ever read, giving a vivid picture of turn-of-the-century European society. I had bought the book only to find it too difficult. Now I brought it to Malibu and forced myself to read it. Scott was surprised and amused to find me poring over Proust while my trade publications lay untouched. “How do you like it?’* he asked. “It’s so hard to grasp,” I admitted. “My mind seems all thumbs when I try to get into it.” I had not really studied a book since I was fourteen.

“Don’t read more than ten pages a day,” Scott suggested. “Read slowly and carefully and assimilate what you’ve read before going on.” I stuck doggedly to his schedule until half way through Volume One the horizons suddenly widened: I began to see everything bigger than life. When I read of the cup of tea that brought back the past so sharply to Proust, I smelled again the potato soup and soapsuds of my childhood. I grew excited. His characters became alive for me, especially Madame Verdurin, who at every crisis buried her face in her hands. I became so fascinated with Madame Verdurin that I began imitating her. If Flora burned the soup, if I forgot a telephone call, if Saturday dawned wet and raining, I clapped my hands to my face. Scott would roar.

I talked about Proust all summer. He was my Thirty Years’ War.

Meanwhile at Metro Scott’s unhappiness mounted. After three months of labor on Fidelity, he greeted me one evening with, “I’ve been taken off the story.” The studio found the subject too daring. The change in title had not helped. He had been shunted to a new story, Clare Boothe’s The Women. He was very depressed. He had never gotten over the fact that Three Comrades had been rewritten—that Scott Fitzgerald had to be rewritten was galling to him—and now it appeared that he had fallen down on still another assignment. I said, because I thought it might cheer him, “Let’s have some people over. Why don’t you invite a lot of your friends?”

“That’s it,” said Scott. His face lit up. “We’ll have a party.”

It was quite a party.

As always, Scott had a plan. High point of the day would be a Ping-pong tournament. Scott carefully prepared a Hst of players, complete to handicaps. Eddie Mayer, the first guest on that Sunday afternoon, arrived with his seven-year-old son, Paul, while Scott and I were playing a practice game. The boy watched us critically for a few moments, then piped up challengingly, “I’ll take on the winner.” This amused Scott. He made short shrift of me and then played Paul in great style—crossing his eyes, slamming the ball with his back to the table or over his shoulder, so that he managed to lose. Then he brought out boxing gloves and he and Paul sparred, Scott ferociously flicking his thumb against his nose and daring Paul to give him one “right on the button.”

The other guests arrived, among them Nunnally Johnson, the writer, and his wife, Marion, Cameron and Buff Rogers, and Charlie Warren with a lovely starlet, Alice Hyde. Charlie was recovering from a back injury and wore a brace, but insisted on coming when he heard that

Scott had invited Miss Hyde to be his date. I hurried about dispensing Flora’s hors d’oeuvres, sandwiches, and coffee, while Scott became busy serving drinks to everyone. He insisted on drinking only water himself.

The party was in full swing when Scott noticed two small faces peering wistfully through the white picket fence that separated our house from our neighbor, Joe Sweriing, the screen writer. The youngsters were his sons, Joe, Jr., six, and Peter, eight. “Come on over and join the party,” Scott called to them. He lifted them over the fence and introduced them to Paul, then went on to supervise the Ping-pong tourney A little later he saw the three boys standing about disconsolately. There was little for them to do, among these adults who were drinking, eating, dancing, and talking endlessly about scripts and studios. Scott went up to them. “Would you boys like to see a wonderful card trick?” He dashed into the house, emerging with a deck of cards. “Only one other man in the world can do this,” he said portentously. “And he’s a lifer at San Quentin, who spent ten years in solitary where he thought up this trick.” He rolled up his sleeves. “Watch!” He knitted his eyebrows, intoned a sepulchral “Abracadabra” and whirled three times with his eyes closed. Then he produced from the deck, on demand, an ace, a king, a ten, a four—all to the delight of his rapt audience.

He mystified them with half a dozen other tricks, showing a surprising sleight of hand. Then he brought string from one pocket and began making and dissolving intricate knots. I was as fascinated as the children. “Now,” he said, “Aren’t you kids thirsty? How about something to drink?”

Joe, Jr., spoke up politely. “I’d like a glass of champagne, thank you.”

Scott stared at him, horrified. “Coming right up,” he said. He immediately telephoned Mrs. Sweriing. “Are you aware that your six-year-old son drinks champagne?” he demanded. Mrs. Sweriing laughed. “We gave him ginger ale at his birthday party last week and told him it was champagne.” Mollified, Scott emerged with a tray of ginger ale which he announced as champagne newly imported from France.

Meanwhile, everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves except Charlie Warren and Alice Hyde. Although at first they appeared to hit it off beautifully, now she seemed deliberately to avoid him. Scott came up to Charlie. “What’s the matter, old man?” he asked. “Seems she can’t stand you. You haven’t said anything offensive to her, have you?”

“Oh, no, sir,” said Charlie, woebegone. “I can’t understand it.”

Alice took me aside. She pleaded an excruciating headache. Would we forgive her if she left? She gave Charlie an icy good-by and was gone.

“Do you want me to try to fix things up, Charlie?” Scott asked, solicitously. “I see her at the studio. I’ll talk to her.”

Charlie said heavily he was afraid it would do no good.

Finally the,evening-drew to a close. There had been word games and charades and much drinking. I saw Scott taking couples to their cars. He seemed in excellent humor. He had been gay all evening despite his unhappi-ness at Metro. AH at once I realized he had been too gay. Of Course. Gin, not water. At this moment he was escorting Nunnally and Marion to the door. Suddenly, as they came opposite a bedroom, I saw Scott violently shove Nunnally into the room, slip in after him and slam the door. I heard the lock click—and then Scott’s voice, raised in anger. Later Nunnally told me what had happened. Scott had locked the door, dropped the key dramatically into his shirt pocket and began to harangue him.

“Listen, Nunnally, get out of Hollywood. It will ruin you. You have a talent—you’ll kill it here.” He began to tick off on his fingers the friends he had known whose talent had been violated by Hollywood.

Nunnally protested. He liked Hollywood. “Look,” he said, “I don’t think I’ve been chosen by destiny to be a great writer, Scott. I haven’t felt the call. I’m just a guy who makes his living writing and I make a better living writing in Hollywood than anywhere else. Why should I leave?”

This enraged Scott. “Why, you sonofabitch, you don’t know what’s good for you.” Scott looked about wildly, as though seeking something to throw at him. “I’m warning you—get out of here. This place isn’t for you. Go back to New York—”

Nunnally decided to reverse his field gracefully. Come to think of it, Scott, you’re right. Of course. Soon as I finish this script I’m working on, I’ll go.”

Scott glared at him. “Oh, no,” he said. “Now you’re lying.” He advanced on him menacingly and Nunnally backed away. “You tell me the truth—”

“I am telling you the truth,” Nunnally insisted, almost backed against the wall now and wondering how hard he would have to punch to render Scott harmless. “I promise, honest to God, Scott.”

I pounded on the door. “Scott, everyone’s leaving, they want to say good-by to you.”

Finally the door opened. Nunnally skittered out with a belligerent Scott on his heels. He was quite drunk. Cameron and Buff Rogers came to say good-by. Scott tried to goad Cameron, who was a big man, into a fight. Cameron refused. Scott turned to Buff. “God damn that big Harvard lug—if he doesn’t knock me out, I’ll kill him. I got to be knocked out!” He squared off. “Come on, Cameron, put up your fists like a man!”

Cameron didn’t know what to do. I fluttered about helplessly. Finally Cameron doubled up his right fist and tapped Scott in the stomach. Scott collapsed and we carried him to a sofa. He was mumbling bitteriy to himself. “That big, hulking brute—and me dying of tuberculosis.” Buff, who felt like a sister to Scott, said, “Oh, be quiet, Scott. If he hadn’t done it, I would have.”

Minutes later Scott was up again, ordering everyone home. The last to leave were Nunnally and Marion. They had almost reached their car when Scott huried a parting insult. “You’ll never come back here. Never!”

Nunnally turned. “Of course I will, Scott,” he said. “I want to see you and Sheilah again.”

“Oh, no, you won’t,” roared Scott. “Because Fm living with my paramour! That’s why you won’t.”

I could hardly believe my ears. I wanted to slap Scott, but, instead, I turned and ran from the room onto the beach. How dare he! Just then I saw him. He had dashed out of the beach house and was racing across the sand to the water. To my utter horror, as I watched him, he plunged, clothes and all, into the ocean and began swimming furiously, like a man about to swim the English Channel. “Scott!” I shrieked. “You’ll die of pneumonia! Scott—”

He swam a few strokes, turned, swam back and emerged, dripping. He paid no attention to me. Instead, he trotted to his car nearby, got in, and drove off in a roar of gears.

He did not return until an hour later, with a bottle of liquor he had bought at the MaUbu Inn.

I heard him tumble into bed in his room.

A few days later Charlie Warren called. He had a date with Alice Hyde. Everything was fine. He began to laugh. “Do you know why she walked out on me at your party?” In the course of the evening Scott had taken her aside. He felt a great responsibility, he said, because he had introduced her to Charlie. He must swear her to secrecy, but the fact was that Charlie, although a fine fellow, suffered from syphilis. He was slowly wasting away. It was aU too tragic. His fingers were due to fall off any day. Even now the poor boy went about strapped tightiy in a brace. Otherwise he would collapse. If she danced with him and surreptitiously touched his back, she would feel the brace that held him together. Scott had told her this ridiculous story with the most solemn mien. “Well,” said Charlie. “She danced with me and that was it.” He was indignant when he first learned Scott’s joke—Scott had finally taken pity on him and told him—but now he thought it hilarious.

“I don’t, Chariie,” I said. “I don’t think it’s funny at aU.”

“Maybe it isn’t,” Charlie said. He laughed again. “But don’t take it too seriously. That’s Scott.”

Next chapter 22

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).