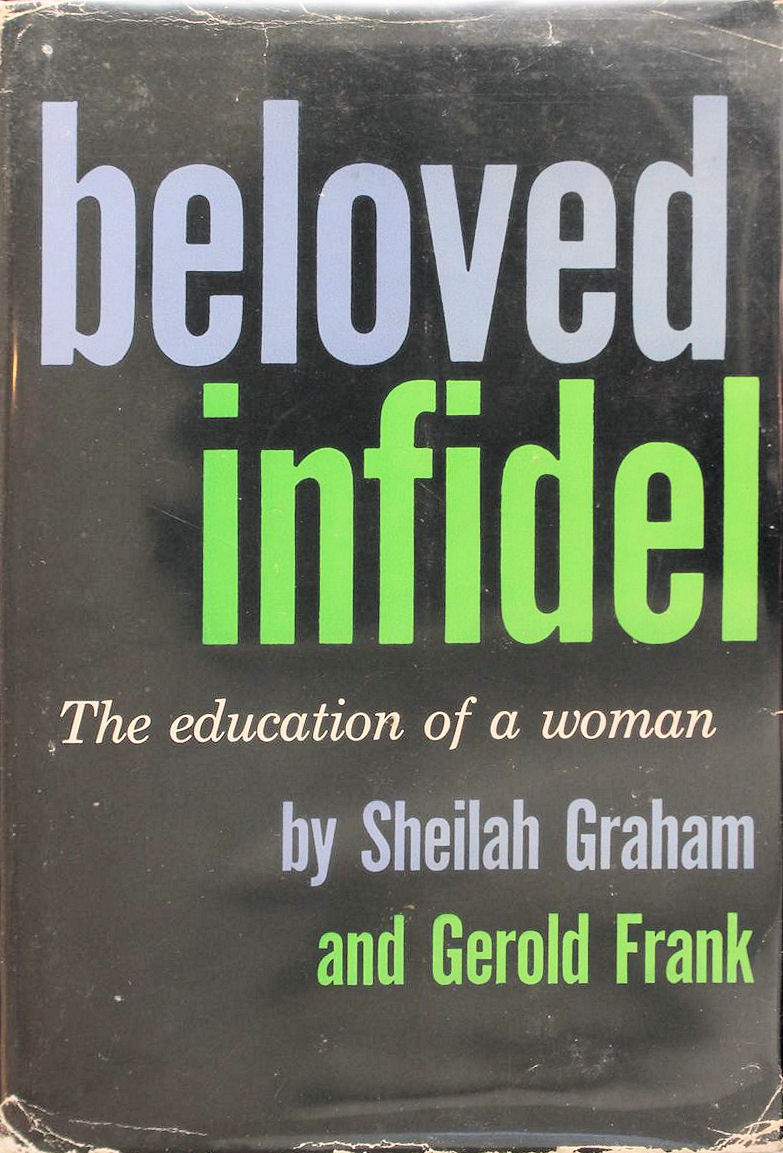

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

In MID-SEPTEMBER, Scott flew East to visit Zelda. She was in a sanitarium in Asheville, North Carolina. Now and then, I had learned from Eddie Mayer, he took his wife out of the sanitarium for a few days. Her doctors believed these brief visits back into the world might help her. Scott and I had yet to speak of her. Once I had ventured to broach the subject of his wife: he had pushed it aside. I did not press him. In everything I took my cue from Scott: whatever he wished was how it must be. Now he had said, “I’ll be out of town for a week or so— I’m going to visit Zelda.” I had said, “All right, Scott. Let me know when you get back.” I knew he loved her; I had been told he loved her. I accepted the fact that there was a Zelda but she had no reality for me, for I had never seen or met her. When Scott returned, he was subdued but threw himself into his work at Metro.

In his absence I had written my five-minute radio script. I showed it to Scott the night before my first broadcast. He read it carefully. “You don’t mind if I reword it here and there?” he asked. And though tired from his own writing at the studio, he sat down with a stubby pencil and a pack of cigarettes and painstakingly—and completely—rewrote my copy. He worked with the utmost concentration and as he worked he twisted the hair above his forehead so that a tuft stood up, as on a kewpie doll. It gave him a strangely boyish appearance. “Cut out all these exclamation points,” he said. “An exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke.” He underlined words I should emphasize, corrected my grammar. “When you tell an anecdote, tell it so your listeners can actually see the people you are talking about.” When he was finished, I was confronted with five minutes of beautiful, flowing prose. I was immensely grateful but asked, rather timidly, “This won’t be over the heads of my audience, will it? People who listen to movie gossip aren’t usually intellectuals, Scott.” He laughed. “It will be good for them.”

The show was at seven p.m. in Chicago, which meant five P.M. on the West Coast. Since Scott was still at work at that hour, he could not be with me for my broadcast in the CBS studio in Hollywood. But he left a conference at Metro to hurry across the street to a garage and listen to me over their radio.

My debut was not auspicious. After the Chicago announcer said, “And now we take you to the well-known columnist, Sheilah Graham, in Hollywood,” there was a forty-second pause while seventy-five engineers across the country pulled connecting switches. At the first words from Chicago, my director in Hollywood raised his arm and held it there: I was to begin the moment he dropped it. I watched him with the terror I might have felt waiting for a cobra to strike. Finally, after what seemed an interminable time, his arm came down sharply. What with the suspense and my pounding heart, my voice climbed to a high register and in a thin shriek I panted, “Hello, everyone (gulp) this is (gulp) Sheilah Graham in Hollywood.” I had difficulty swallowing and breathing but I managed to read my script to the end.

Scott called immediately. “You were quite good,” he said. “Oh, Scott, I was terrible and you know it,” I said. “No, no,” he insisted. “You sounded a httle breathless, but that was all.”

The sponsor agreed with me. Would I mind, they asked by telephone the next day, if a professional radio actress in Chicago spoke for me on the succeeding programs? She would be announced as Sheilah Graham. In the future I need only provide the script.

Scott was outraged. “Absolutely not. There’s nothing wrong with your voice. You have a contract, they must use you. You’ll get over your nervousness if they’ll give you a chance.”

I believed him. Obviously, it was the tense, silent waiting, the poised arm of the director that unnerved me. But Mr. Wharton, on the telephone from Chicago, was adamant. His sponsor insisted upon another voice. I grew angry, then furious. I would not be relegated to second-best! I’ll fly to Chicago at my own expense and do next week’s show from there,” I told him. “I’ll prove to you that I’m fine if I don’t have to worry about engineers throwing switches from here to New York.”

Mr. Wharton doubted that my presence would influence the sponsor, but he could not prevent me from going to Chicago. If I insisted, very well. He’d talk to me there. I told Scott. And Scott said, quite suddenly, “You need someone to help you in this fight. I’ll go with you.” I was tremendously relieved. With Scott to handle Mr. Wharton he would certainly win our point, and the prospect of our first trip together excited me. “Are you sure you can leave?” I asked. It was an overnight flight to Chicago. “Can you leave your work? You know we can’t get back before Tuesday.”

“Don’t worry about that,” said Scott, almost impatiently. “I’ll arrange it.”

He called for me in a cab Sunday afternoon and we went on to the airport. He seemed tense as he sat beside me, smoking one cigarette after another. I knew that he had been taken off A Yank At Oxford after a few weeks’ work and was now writing Three Comrades, a film to be made from Eric Maria Remarque’s famous war novel. In recent days Scott had appeared harassed. I was aware that he disliked clocking in each morning at the studio, that he found the interminable story conferences an ordeal, and was unhappy when he had to fight for a line or a scene in his script. His six months’ contract was coming up for renewal and he was not sure that Metro would renew it.

We arrived early at the airport. There a press agent, Mary Crowell, asked me if I’d come with her briefly to meet a young actress. As she took my arm Mary said to Scott, “We’ll meet you in the bar, Mr. Fitzgerald. I’ll keep Miss Graham only a few minutes.”

Five minutes later we sought out Scott, to find him seated at a Uttle table in the bar with a glass of water in front of him. Mary asked me, “What will you have?” I said a brandy, because brandy settled one’s stomach and I felt apprehensive about Chicago. Scott said cheerfully, “Bring me a double gin.” I looked at him with surprise. His face was flushed. He’s drinking, went through my mind. That isn’t water. It’s gin. And then, / never saw him drink before. Our order had no sooner arrived than Scott tossed his down and before the waiter could leave, he said, “I’ll have another double gin.”

I felt a twinge of concern. His eyes were bright, he ran his hand repeatedly through his hair, disheveling it, and he was talking nonsense, a kind of complimentary nonsense, to Mary and me: she looked adorable, I had a skin like peach note paper. Now the waiter was back with his drink. Before he could lift it from the tray, Scott said, “And when you come back, bring another one.” As the drink was set before him, I half-playfully, half-anxiously pushed it aside. Scott, with sudden vehemence, grabbed my arm and thrust it away.

Well, I thought, indignantly. He’s being most childish. Here I am, going to Chicago to do battle, and he’s come along to help me, and look at him. He’s tiddly —Bruce Ogilvy’s word for his fellow officers when they had a few drinks and began playing leapfrog over the mess-hall tables. But at this moment Scott winked at me—a slow, outrageous wink—and my anger filtered away.

When our plane was called, he got into his raincoat with some difficulty but refused to button it, so that he literally flapped his way to the plane, his coat flying behind him, his hat perched precariously on the back of his head. As we settled down in our seats I saw a bottle in his coat pocket.

The plane took off.

“Scott—” I began.

“Shh—” he said, with exaggerated caution. He tugged the bottle free and took a long drink.

I began again “Scott, please—”

He looked at me, his head “to one side. “Do you know who I am?” he asked. “I’m F. Scott Fitzgerald, the writer.” He slapped my knee. I held his hand, thinking, / hope he doesn’t make a scene.

The stewardess came by with an armful of magazines. Scott smiled up at her. “Do you know who I am?” he asked. She was a pleasant, dark-haired girl of about twenty-one. “No, sir,” she said. “I don’t have my passenger list with me.”

He said, expansively, “I’m F. Scott Fitzgerald, the very well-known writer.”

I blushed. The girl smiled politely and moved on.

Scott turned to the man across the aisle, and stared at him challengingly. “Do you know me?” he demanded.

The man threw him a tolerant glance. “Nope. Who are you?”

“I’m F. Scott Fitzgerald. You’ve read my books. You’ve read The Great Gatshy, haven’t you? Remembr?”

The other looked surprised. “I’ve heard of you,” he said, grinning, but there was a note of respect in his voice.

Scott turned to me. I was so embarrassed I could not determine whether he was being triumphant or sardonic, “See? He’s heard of me.” He turned back to the man and engaged him in a long, confused conversation.

I sat there, heartsick. Scott had finished his bottle by now; his words ran together and the man listened to him with a kind of amused disdain. How could my gentle, well-bred, impeccably mannered Scott, who possessed such great personal dignity, change so completely? He could not go on to Chicago in this state. There was only one thing to do. Our plane stopped en route at Alber-querque. I got Scott’s attention. “Scott, I think you’d better get off the plane at Alberquerque and go back to Hollywood. It was a mistake for you to come. You’re in no condition to help me—you’d be a hindrance. I don’t like you this way at all.”

Scott, in his seat, bowed elaborately. “I’ll get off,” he said, his words running together. He thought heavily for a moment. “Yes, go fight your own battle. You’ll always be alone. So will I. We’re both lone wolves.”

He fell into silence and I sat next to him, utterly miserable. I had thought, at last I have found someone to look out for me, to protect me, someone I love and respect . . . I had counted on his help, and he had failed me.

When the plane taxied to a halt at Alberquerque, Scott tipped his hat. “ ‘By.” I said, “Good-by, Scott, I’ll see you when I get back.”

I got into my berth and lay there, the light on, and I began to cry. He was right. He is a lone wolf because of his great talent, and I because I have so many secrets and am never satisfied. All my life the moment I am about to become part of a group, I must move one rung higher, and then I am alone again. I’ll never belong anywhere. I felt lonely and abandoned as I lay there. / wish I hadn’t told him to get off. What’s wrong with a man having a drink, even if he does overdo it once in a while?

The plane took to the air again. I reached up to turn out my light, when the curtains parted and Scott’s head popped in. He was pixie-faced. “Hello!” he said.

“Oh Scott, I thought you’d gotten off!” I said it with tremendous relief. I sat up and pulled him to me. “I’m glad you didn’t get off and I love you.” “Sure I got off,” he said carefully. “Needed another bottle.” And presently he went to his berth and fell asleep.

In Chicago, in the morning, en route to the Drake Hotel, he looked gray as chalk. He said little as we went to our adjoining rooms and unpacked. I telephoned Mr. Wharton, who came over promptly. He turned out to be a slender pleasant man in his thirties. Scott came into my room to meet him. In the twenty minutes that had elapsed, his face had become flushed again. Mr. Wharton was honored to meet Mr. Fitzgerald. “This is an unexpected pleasure,” he said cordially. Scott sank into an armchair and we got down to business.

“Now, I’ve brought my script with me, Mr. Wharton,” I began. “I know I can do the show to your satisfaction if I don’t have that appalling forty-second wait. That throws me off completely.”

Mr. Wharton was noncommittal. I smiled at him. “You are going to let me on tonight, aren’t you? I’ve come all this way—” We discussed the subject for some minutes, Scott taking no part. “Well,” said Mr. Wharton finally, as he rose. “I can’t promise anything, Miss Graham. I’ll have to talk it over and I’ll let you know this afternoon.”

I said, taking him to the door, being my most gracious, “I know you’re going to let me on that program tonight. You simply must, Mr. Wharton.”

Suddenly Scott leaped from his armchair and with a tremendous bound confronted Mr. Wharton. “Does she go on or doesn’t she go on tonight?” he demanded pugnaciously.

I stood dismayed. Mr. Wharton, astounded, his hand on the doorknob, backed away. His face paled. “Well, I don’t know, Mr. Fitzgerald—I can’t give you a decision —I have to check with—”

Scott took a step nearer and put his face inches from Mr. Wharton’s, “Take your hands out of your pockets,” he said in low, melodramatic voice, and suddenly his fists were up, in the posture of a fighter, and he swung wildly at Mr. Wharton. The latter ducked the blow and fell back. I became hysterical. I threw myself between them and pushed Mr. Wharton out the door. “Go, please go, I’ll call you later.” I slammed the door and turned to face Scott. I was shaking, my legs trembled. “How dare you!” I screamed. “Are you crazy?”

Scott turned away. He spoke almost to himself. “That s.o.b.” he said. “He’ll see. You’re going on and he’s not stopping you. Just let him try.”

I threw myself on the bed and lay there, moaning. “Oh, this is the most horrible thing that ever happened in my whole life! How could you do this to me! It’s so terrible!” I cried. “Go away! Go away, I hate you!”

Scott ran his hand through his hair, grumbled to himself, and lurched into his own room, slamming the door.

When I had calmed down so that I could function, I telephoned Mr. Wharton and apologized. “These things happen,” he said, tactfully. “Let’s just forget it.” He was happy to inform me they had agreed to let me do the show myself. I was to come to tht CBS studio at five P.M. for rehearsal before going on the air.

We had won! Suddenly my anger at Scott began to vanish. He had tried to be my champion. He was not in his room: perhaps he was out walking it off, I thought. I lunched by myself and at five p.m. I was on the stage of a

small studio theater at CBS. Standing before the microphone studying my script, I looked up—and there was Scott seated in the front row of empty seats, smiling impishly at me. I put my finger wamingly to my lips. Scott nodded and made an elaborate show of putting his own finger to his lips.

But as I was about to go into my speech, he came to his feet. “Now Sheilah,” he said in a loud voice. “Don’t you be afraid of them. Nothing to be afraid of. Speak slowly and distinctly—” He began to beat time to my words with an invisible baton.

I was crimson with shame. “Scott,” I pleaded in an agonized whisper. “Please sit down and be quiet.”

But Scott continued to conduct me until two stagehands appeared and escorted him out.

Since I was completely unnerved now, it took several rehearsals before I satisfied the director. Then, at seven o’clock, I went on the air. I felt I had done well as I took a cab back to the Drake Hotel. My only concern now was Scott.

As I entered my room I heard muffled voices from Scott’s. The door between was closed. I pushed it open and stood, dumfounded. A tray of food was on a serving table; Scott sat in a chair beside it, a napkin around his neck like a bib—and sitting facing him, knee to knee, was a younger man carefully feeding him. Each time Scott opened his mouth, the stranger deftly thrust in a forkful of food. As I stood there, speechless, there was a brief struggle. Scott had suddenly tried to bite the stranger’s hand. “Oh, stop it, Scott!” the other said, more in annoyance than anger. I noticed that Scott’s bib—and his friend’s shirtfront—were splattered with coffee. “How am I going to get this down if you’re going to play games?”

They became aware of me. “Hi, Sheilo,” said Scott, genially. The stranger rose, brushing pieces of cut-up steak and breadcrumbs from his trousers. “Sorry you had to walk in on this Mack Sennett comedy,” he said, with amazing aplomb. “You’re Miss Graham, of course.” He introduced himself. He was Arnold Gingrich, Editor of Esquire magazine.

I stammered, “Oh, this is awful, just awful! Have you ever seen him like this before?”

Scott spoke up. “Show her those articles, Arnold!” His language became abusive. Arnold gently persuaded him to lie down on the bed and presently Scott dozed off.

Yes, Arnold said, he had seen Scott like this before, but this was the worst he could recall. We could only try to sober him up in the three hours remaining until plane time. The airport limousine made a regular stop at the Drake: once we got Scott into the car, perhaps the fresh air would bring him around and I would be able to get him on the plane.

While Scott dozed fitfully, Arnold told me what had happened. Scott had telephoned him an hour ago to say he was at the Drake Hotel, and Arnold must come over at once. He came, to find Scott surrounded by water tumblers of gin and a sly look on his face as if to say, “Ha, ha, everyone thinks I’m drinking water but these are gin.” Scott told Arnold about me: he had come along to Chicago to help me iron out my difficulties at CBS and was waiting for me to return now. We were flying back to Hollywood on the midnight plane. “Well,” Arnold said to him, “we’d better start sobering you up right now. I’m going to order you a steak sandwich and a quart of black coffee. You can’t let her see you in this condition when she gets back. Besides, they’ll never allow you on the plane.” Scott became perverse. He would eat only if Arnold would feed him. Arnold humored him. When the steak arrived he cut it into small pieces and began to feed Scott. Every now and then Scott tried to bite him. When Arnold attempted to pour black coffee into his mouth, Scott promptly spouted it back, like a small boy. It was in the midst of these incredible proceedings that I had walked in.

The articles Scott had demanded, Arnold explained, were a series of three pieces he had written for Esquire, “The Crack-up,” “Handle With Care,” and “Pasting It Together,” in which Scott described a nervous breakdown he had suffered two years before. Scott wanted me to read them in the hotel room. Arnold went on to explain that Scott had been a frequent contributor to the magazine in 1934 and 1935; that he was drawing money in advance for articles yet to be written; and for some time had sent nothing to the magazine. Arnold said, “I visited Scott in Bahimore in late 1935 to see why he’d stopped sending us articles.” He had found Scott wretched, drinking, and at his wits’ end. “I just can’t write any more,” he told Arnold. “Everybody wants me to write about young love and I can’t write about young love.” He had dried up as a writer; he had tried desperately but couldn’t prime the pump; his tremendous expenses had used up every penny of the moneys advanced by Esquire as well as by The Saturday Evening Post; he wanted to write, he wanted to make up the advances, but he couldn’t write. He might never write again. He had reached a terrifying blank wall.

Arnold told him, “Scott, I must have a manuscript from you because our auditors are on my neck wanting to know what we’re paying you for. Even if you do a Gertrude Stein, even if you just fill a dozen pages saying, ‘I can’t write. I can’t write, I can’t write,’ five hundred times over, at least I will be able to report that on such and such a date a manuscript arrived from F. Scott Fitzgerald. I will have something in my files to prove you’re doing work for us. Otherwise, I’ve got to stop sending you money.”

Scott promised he would try. “All right.” he said. “I’ll write whatever I can write about why I can’t write.” The results were the “Crack-up” sketches and, later, a series, “The Afternoon of an Author,” which Arnold published in Esquire as fiction. Apparently writing the first sketch helped Scott conquer his writing block, for he began to contribute regularly again to Esquire and continued after he came to Hollywood.

I listened as Arnold swiftly oudined this background. My heart went out to Scott. How little I knew about this man who spoke never of his troubles but was so sympathetic and understanding about mine.

Arnold said, looking at me, “You know, of course, that Scott with liquor is as different from Scott without liquor as night is from day?”

I said, “I know it now. This trip is the first time I have seen Scott drink. And if there’s anything I can do, he won’t drink again.”

When the airport car came we managed to help Scott into it. Before he left, Arnold gave me his telephone number. “Just in case,” he said. “Don’t be afraid to call me at any hour.”

The limousine was empty save for one other couple. We took seats behind them. Scott had bid an extravagant good-by to Arnold: he must send those “Crack-up” sketches to Hollywood so I could read them. Now he sat, half-dozing. We had almost reached the airport when he roused himself. He looked around at the empty seats, then focused on the back of the young woman in front of us. He turned to me and said audibly, “Doesn’t she have lovely hair?” The girl shifted self-consciously in her seat and glanced at her escort with a smile. Scott went on, almost musingly: “Isn’t she pretty? Such lovely hair, such poise—a very lovely young woman.”

At this the girl half-turned to flash Scott a pleased smile.

Scott said to her, “You silly bitch.” I could not believe my ears. The girl turned, startled, and stared at him, with fright in her eyes. The man turned to face Scott, white with anger: what might have happened I do not know because we had come to a stop at the airport and the driver waited for us to get out. “Scott, be quiet!” I implored him. “They won’t let you on the plane if they see you’ve had too much to drink.” I still could not use the word drunk: drunk sent me back to my childhood horror of the man crawling in the street. Scott was not drunk: he had had too much to drink.

Nor did they let him on the plane. Getting out of the limousine he tripped and fell. He fought with the driver who raised him to his feet. I took his arm and we managed to get to the counter. The clerk looked at Scott and said politely, “I’m sofry, sir, but I can’t permit you on the plane.”

My heart sank. The next plane for Hollywood would not leave until five a.m. Five hours! And I had Scott on my hands, belligerent and quarrelsome and, at this moment, steadying himself at the counter as he demanded to know where he could buy a plane.

In desperation I rang Arnold Gingrich. I had to get Scott back to Hollywood. Arnold’s advice was to get Scott into a taxicab and ride about for the next five hours. By then Scott would be sober. But I must keep him away from a bar. Meanwhile, Arnold promised that he would telephone every bar in the vicinity of the airport so that if Scott did get into one, they would serve him only beer.

I followed Arnold’s advice. Most of the time Scott slept on my shoulder in the back of the cab. Now and then he woke to demand, “Driver, stop at the first bar.” I had warned the driver. Every few minutes Scott would rouse himself and exclaim, “You s.o.b., I told you to stop at the first bar!” then look up at me, “Hello, baby,” and then tell the driver off again. I would soothe him and he would fall asleep. And so it went until nearly five A.M. when we drove back to the airport and Scott, though drowsy, was permitted aboard. We were asleep on each other’s shoulders when our plane landed in Los Angeles.

A week later I flew to Chicago, alone, to do my show. Scott had awakened once on our trip back to Hollywood. In what appeared to be a moment of absolute sobriety, he had apologized. He had said, “Don’t worry. I can stop this whenever I want, but I must get out of it in my own way. I’ll report sick to the studio and tell them I won’t come in for several days. Then I will get a doctor and nurses. It will take at least three days.” He did not say so but I gathered these would be three days of hell. “I won’t call or see you during that time,” he said. “Don’t call or try to see me.” He had smiled wanly. “I’ll telephone you when I’m all right again.”

I had said, a little coldly, “As you wish, Scott.”

Now, in Chicago, with my broadcast over, I thought, Fm halfway to New York. Why not go on and see the new Broadway shows?

I was packing when Scott called from Hollywood. He had heard me and I had done well. He would meet my plane in the morning. “I’m not returning to Hollywood until the end of the week,” I said. “I’m going to New York.”

Scott said, in a voice suddenly flat, “You have someone in New York.”

“Oh, Scott, I have no one. I’m just going to see some shows and catch up with what’s happening there.”

There was a brief silence. He said, quietly, “Sheilah, if you go to New York I will not be here when you come back. I’ll give up my job and leave Hollywood and never return.”

I gasped, “You can’t do a thing like that, Scott!” “I will,” he said evenly. He meant it. I was overwhelmed by the enormity of that decision. I said, “Let me think about it and I’ll call you back.” But as I spoke the words I knew I would not go on to New York. I did not know that Scott, when he had come with me to Chicago, had left his studio in the middle of a picture, without a word to anyone. I did not know that his drink at the airport, which led—which had to lead—to all the others, had been his first in months: that he had taken it to bolster his courage, knowing that his unauthorized departure gave Metro just cause not to renew his contract. Yet he had riske4 that to help me. As I spoke to him on the telephone I knew only that if I was important to him, he was everything to me; that I did not care if he drank, though I prayed he would not drink; that nothing mattered save that Scott and I were together. I had had my first anguish with him, but that^ too, was part of love; whatever he did, however he acted, I was in love with him and aU else in my life faded into the background.

I returned to Hollywood that day.

Next chapter 19

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).